“If this guy’s still out there— You not only sped up his timeline, you put yourself in it.”

Director: Scott Derrickson

Starring: Ethan Hawke, Juliet Rylance, James Ransone, Clare Foley, Michael Hall D’Addario, Fred Dalton Thompson, Vincent D’Onofrio, Nicholas King

Screenplay: Scott Derrickson and C. Robert Cargill

Synopsis: True-crime writer Ellison Oswalt Ethan Hawke), his wife, Tracy (Juliet Rylance), and their children, Trevor (Michael Hall D’Addario) and Ashley (Clare Foley), move into a house outside Chatford, a small town in Pennsylvania. As they are carrying their possessions inside, two police cars pull up. The local sheriff (Fred Dalton Thompson) calls Ellison away from his family, making it clear that he is anything but gratified to have him in the neighbourhood, and telling him that his buying the house – the site of a notorious, unsolved mass murder and child abduction – is in very bad taste. As the police depart, Juliet questions Ellison about the incident, becoming concerned that he has – yet again – moved his family into a house a few doors away from a crime scene. Ellison denies it… As the family set up the house, Ellison takes as his office a room with large windows overlooking the backyard—including the tree from which, a year before, four members of the Stevenson family were found hanged. The youngest member of the family, a child called Stephanie, has been missing ever since. Ellison carries some of his things up into the attic, where – after he is startled by and kills a scorpion – he discovers a box containing a projector and several reels of film, each tin labelled in a way that suggests home movies. Later, worrying over the effect Ellison’s work has upon the children, Juliet expresses her concern; but Ellison insists that he is working on something important, something that will lead to another best-seller, and that their money and other troubles will soon be over. While setting up his office – which he has promised to keep locked – Ellison also sets up the found projector, running a reel titled Family Hanging Out ’11—only to discover to his horror that he is watching footage of the hanging deaths of the Stevenson family, who are dragged into the air as the branch acting as a counterweight is sawn off; though he cannot see who is holding the saw… Ellison realises that although the sets of footage were taken years apart, each one shows the grotesque mass murder of a family—but in none of them can the killer be seen. After watching a reel tiled BBQ ’79, in which the family is burned alive in their car, Ellison calls the police—but then, thinking of his one huge success, ten years before, when he helped solve a case and had a #1 best-seller – and of the two disastrous failures since – he changes his mind and hangs up… The Oswalts’ first night in their new home is full of disruptions: a sleepy and disoriented Ashley gets lost trying to find the bathroom; while Trevor suffers one of his rare but extreme night terrors. While comforting his son, Ellison is tempted to tell Tracy what he has found, but in the end only offers a broad and general apology. The next morning, after Tracy has taken the kids to school, Ellison steels himself to watch the reel titled Pool Party ’66, in which four people, bound, gagged and strapped to folding lounges, are dragged into a swimming-pool and left to drown. Suddenly, Ellison catches a glimpse of a strange figure with a pale, distorted face, which seems to be watching from under the water…

Comments: Though the Amityville franchise is undoubtedly cinema’s most famous example, recently we have seen a new take on the trope of The Murder House in Scott Derrickson’s Sinister. Although his apparent dedication to the genre film is encouraging, Derrickson’s writing and directorial career has so far been erratic, to say the least; and there was little to indicate a priori where on the spectrum this 2012 horror film was likely to sit.

The answer is…somewhere in the middle. There’s some good stuff in Sinister, there’s no question of that. It has a great premise, some effectively executed scares, and some truly disturbing imagery—although at the same time, at least for the most part, it eschews gore in favour of a focus upon Ellison Oswalt’s horrified reaction to the content of the film reels; which I appreciated, though other viewers may be disappointed. We’re never left in any doubt of what he is seeing, however.

This is, of course, a “found footage” film in the literal sense of that expression; and the triumph of Sinister is its film reels and what they contain. While, in the cold light of day, we might question the logic of not just the actual use, but the continued use over time, of Super 8, these inserts are both brilliant and chilling, with the graininess of the film lending an almost unbearable verisimilitude to the horrifying images. Furthermore, the murders captured took place approximately a decade apart, and Sinister – unlike some films I could mention – does a brilliant job in each of these inserts in invoking the time period in question: the hair, clothing, cars and accessories are all correct, and all properly evocative.

So that’s the good news. Balancing it out – overbalancing it, in the long run – are some serious flaws in both character and story which, for me, ultimately made Sinister a bit of a disappointment.

The film’s elephant in the living-room is its protagonist, Ellison Oswalt—very definitely its protagonist, and not its hero. Interestingly enough, the producers of Sinister were very well aware of the problem here, and explained the casting of Ethan Hawke in terms of their need for an actor the audience would be willing to “go along with”, despite his character’s questionable choices.

But with all due respect to the producers’ intentions and Ethan Hawke’s best efforts, I cannot conceive how the viewer could truly be expected to “go along with” Ellison Oswalt, who is progressively revealed as a repellent mixture of selfishness and stupidity. He starts out by moving his family into The Murder House, and lying to his wife about it; it goes downhill from there.

With hindsight, I can’t help feeling that it would have been better for the film if its producers had taken the bull by the horns and positioned Ellison overtly as a selfish dick, unthinkingly sacrificing his family’s welfare and happiness to his pursuit of a second taste of success and celebrity. Handled right, that would have allowed for character growth and given the film’s climax some genuine tragedy—as opposed to the mere cosmic irony with which Sinister ultimately leaves us.

The issues with the character of Ellison Oswalt are exacerbated by the underwritten nature of the role of Tracy, with which Juliet Rylance can do little, and which gives us little real sense of the nature of the relationship between the two. Since the film makes such an issue of the impact of Ellison’s work upon his family, it is curious that Tracy is such a pallid and inconsistent character. Frankly, in the end it feels like Ellison has a wife only because the plot demands he have children, but also that those children be kept out of his hair. Apparently you haven’t come such a long way after all, baby.

These character shortcomings are exasperating; so too is that for the duration of this film, no-one ever turns the fricking lights on.

(Mind you—no less annoyingly—this is the kind of house where there’s no light even when the lights are on.)

Don’t get me wrong here: Scott Derrickson makes good use of the dark in Sinister, building suspense by constantly isolating his characters within a tiny pool of light, and surrounding them with a threatening blackness out of which anything might loom…and finally does.

But it just isn’t credible that someone in a situation like Ellison’s, confronted with the fact that a serial killer – or something worse – has access to his family’s home, continues preferentially to wander around in the dark; not to mention choosing to sit in the dark while he watches snuff films over and over and over…

I know that some people can shrug this stuff off, but I just can’t. When it comes to a film’s fantastic elements, I can and happily will suspend all sorts of disbelief—but this kind of artificiality jerks me right out of the story. And the further we got into Sinister, the more these details got between me and the film, and interfered with my ability to enjoy it. That said, however, there’s still plenty here to enjoy.

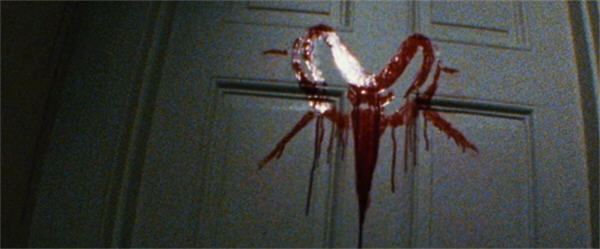

Sinister doesn’t waste any time rubbing the viewer’s nose into its premise: it opens with the footage of the Stevenson mass-hanging—the family, bound and hooded, being pulled into the air as the branch acting as a counterweight is sawn off; their final struggles…

(I may say that I was somewhat dismayed to discover how many GIFs there are of that out in Internet Land…)

We then cut to the Oswalts moving into their new home, and Ellison being called out to talk to the local sheriff. Immediately we are aware of the adversarial relationship between Ellison and the police—or between the police and him. There is mention of Ellison’s great triumph, Kentucky Blood, in which he both solved a notorious crime and wrote a #1 best-seller, winning fame and money in the process; but we also hear about his two ventures since then, disasters, both of them, one propagating an incorrect theory that “helped set a killer free”. The sheriff’s parting remarks are a condemnation of what he calls Ellison’s “extremely bad taste”, in the way he is pursuing his current venture…

Tracy has watched all this from a distance in some apprehension – she has becomes used, in recent years, to, “Driving five miles under the limit and getting ticketed anyway.” Then an appalling thought strikes her:

Tracy: “Ellison, we didn’t just move in a few houses down from a crime scene again, did we?… No, just don’t say anything. If we did, I don’t want to know about it.”

Ellison: “We didn’t.”

Tracy: “You promise?”

Ellison: “I promise.”

We then follow Ellison into the house, into the attic where he finds the box containing an old projector and some film-reels, and then into the room he has chosen as his office—which has large glass windows offering a view of the backyard, including the tree from which the Stevensons were found hanged…

Ellison wastes no time in setting up his work space, lining the walls with pin-boards on which he begins to assemble the data in the Stevenson case, including crime-scene photographs. Among them he finds a photograph of the house’s attic, empty: he includes this amongst his evidence, noting on it the position on it of the found box. And then, what the hell? – he sets up the projector and sits down to watch Family Hanging Out ’11… BBQ ’79 soon follows, in which another family is burned alive…

Ellison snatches up his phone and puts through a call to the police, but even as he is being transferred his eyes fall on a pile of copies of Kentucky Blood—and he hangs up.

We know quite a bit about Ellison Oswalt, by this time, none of it sympathetic: that he has deceived his wife over this most recent venture, that he is careless about the impact his work has about his family (Tracy keeps reminding him to keep his office door locked, and yet it rarely is); now, that he is prepared to stay silent when he finds evidence of several appalling crimes in his possession, so that he may turn that discovery to his own advantage.

Though he maintains a pose of it being “all about justice”, we already suspect that it is celebrity that drives Ellison Oswalt. The huge success of Kentucky Blood, both as a piece of crime investigation and as a book, made him a household name: he keeps a drawer full of recordings of TV appearances made at the time, and re-watches them upon occasion. But that was ten years ago, with nothing but failure and humiliation in between, and now his longing for a second “hit” has become desperation—as we see from his occupation of The Murder House: unnecessary for his research into the crime, but gold as a publicity hook that he can use to sell his book.

The sheriff made mention of, “The circus you bring with you”, and now we don’t doubt it; we see too that the accusation of “bad taste” was not without foundation. With the discovery of the films, Ellison realises he has stumbled into something infinitely bigger than the Stevenson murders, shocking as those were—and all he can see is a chance to write, “My In Cold Blood.”

And so dazzled is Ellison by the prospect before him that a few fundamental truths never even occur to him. He knows for a fact that the attic was empty at the time of the police investigation into the Stevenson murders, and that the projector and films must have been placed there subsequently: that therefore someone connected with the crime – possibly the killer himself – who he now knows is a serial killer, a serial family annihilator – has access to his house – the house into which he has just moved his family – and he never reacts to that aspect of the situation. He doesn’t call the police. He doesn’t install a security system. He doesn’t change the locks.

He doesn’t even turn the lights on.

So at this stage, Ellison is not exactly winning points for either sensitivity or intelligence; but trust me, it’s gunna get a whole lot worse…

Having decided within himself to stay silent, Ellison settles down to the grim tasks of working through the other films. He starts with Pool Party ’66, in which a family is drowned, and that’s as far as he gets. While watching this footage, Ellison catches a glimpse of something – someone? – under the water, a cloaked figure with a long, pale, distorted face—which for a moment looks at the camera. A startled Ellison pauses the film and approaches his makeshift projection-screen to examine the figure more closely, but the suspended film overheats and catches fire.

Ellison rushes back and extinguishes the flames, rescuing the rest of the film. From this he has learned a lesson, and sets to work making digital copies of the Super 8 footage. He restudies Pool Party ’66, searching for the figure in the pool, but the critical few frames have been destroyed…

There’s an interesting “meta” aspect to the business of the found footage in Sinister, and the contrast drawn between the grainy film, which yet has a genuinely disturbing immediacy, and the digital copies which allow frame-by-frame analysis, but which have a contradictory detachment in their very clarity. Meanwhile, at the outset we often see, not the images themselves, but the reflection of those images in Ellison’s glasses; and as the film goes on there is an increasing tendency for Ellison to put himself where the images are projected directly onto him, making himself a part of them.

There are all sorts of comments upon the state of film-making today that we can draw from this, and from Ellison losing sight of the big picture as tries to understand the fine detail (David Hemmings, eat your heart out). Images of film and film-making are pervasive throughout, fully justified by the plot which, indeed, turns upon imagery, and the power of visual communication—so much so that it occurred to me that it might have been thematically stronger to have Ellison a documentary-maker, someone at home with film, and who understands – perhaps too well – how it, and consequently the viewer, can be manipulated. However, there’s undoubtedly more pop-cultural cachet in being the author of the New York Times’ #1 Best-Seller, than winner of the Academy Award for Best Documentary; so we appreciate why the celebrity-driven Ellison was made a writer.

On the other hand— I’m not sure there isn’t also a tacit criticism of horror fans in Sinister—and I find few things more annoying than horror movies that criticise the watchers of horror movies. This is, at least, one of many films that at one level is about voyeurism, about watching as a form of transgression. There are many shots of the projector that position it as something more than a passive conveyor of images; while in Ellison Oswalt we have an example of someone horrified by images but unable to look away—not even, or perhaps least of all, when circumstances eventually offer him the “extended cut ” versions of the film-reels. He knows what he’s going to see, but he watches them anyway…because he doesn’t know everything he’s going to see… And he’s not the only one who prefers “when they make the movies longer”…

Family-wise, things are beginning to hit the fan for Ellison—not much to our surprise. Ashley is unhappy at leaving her home and her school, her only consolation that – she’s a budding artist – she is allowed to paint on the walls of her bedroom. For Trevor, meanwhile, the stress of the move has brought back his night terrors (which, by the way, are the basis of two of the film’s most effective, albeit – when you think about it – gratuitous scare-scenes). Trevor has already pumped Ellison about what crime he is investigating, arguing that his father might as well tell him, since he’ll certainly hear about it at school anyway. He does—but only the general details, not the critical point, as Ellison is quick to appreciate.

When a furious Tracy tells him that Trevor has been “acting out” again, that his first day at school was highlighted by him sketching the hanging Stevensons on a classroom whiteboard – in permanent ink – Ellison’s response is a revealing, “That’s all he heard?”

“That’s not enough?” retorts Tracy, who of course doesn’t know the half of it—and who, in the wake of this scene, will have to remind Ellison yet again to keep his damn door closed.

Ellison returns to his footage, this time examining Sleepy Time ’98, in which the murdered family have their throats cut while they lie bound and gagged on their beds. This, too, he converts to digital, which allows him to isolate two critical details: a strange symbol painted on the wall, and a notice in the house which reveals that these murders happened in St Louis. Following up the latter online, he learns that in this case, too, a child was missing after the murders.

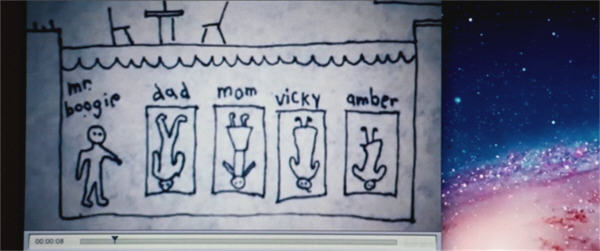

A power-outage then occurs – okay, for once there’s a reason for wandering around in the dark – but that hardly excuses Ellison choosing while the power is out to investigate the creepy noises he’s been hearing from the attic. Up there, Ellison finds nothing to account for the noises, but he does have another strange animal encounter as a snake slips away (it’s only a king snake; perhaps we’re supposed to think it’s a coral snake?). The creature was concealed under the lid of the box which held the projector and films, which Ellison didn’t examine when he first found them. He does now—and discovers inside the lid drawings of the mass murders, apparently done by a child, in each case mentioning the adult victims as “Dad” and “Mom”, rather than by name—and in each case positioning a strange figure called “Mr Boogie” within the crime scene.

More strange noises interrupt Ellison’s examination of his find, but his attempt to locate a source ends with him plunging through the attic floor and crashing to the ground below…

This time emergency services are called – we assume Tracy called them – and Ellison is attended by a paramedic, who treats his injured leg, and a local deputy…

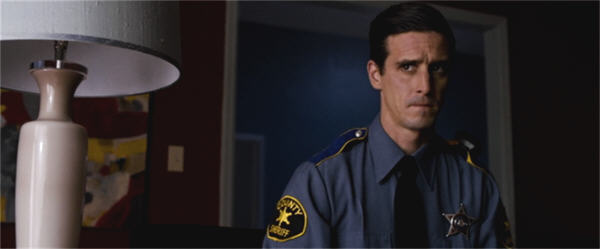

I know opinions differ on this, but I’m in the camp that considers Deputy So-and-So to be one of Sinister’s successes. Appearing at first to offer only some awkward comedy relief, the deputy progressively emerges as the film’s most sensible character (which, granted, isn’t a difficult achievement). An aspiring criminologist with ambitions beyond his small home-town, the deputy’s initial awkwardness is, we gather, due to his celebrity-worship of Ellison Oswalt, which (it happens, right?) makes him incapable of saying anything to him that doesn’t make him sound stupid. That he is anything but stupid soon becomes clear, though; and in fact, for all we hear of Ellison’s “research” and “the good work” he’s doing, it’s the deputy who will eventually uncover most of the critical facts in the series of murders.

We never do learn the deputy’s real name – because Ellison, though he unhesitatingly uses the star-struck young police officer, bribing him with a signed copy of Kentucky Blood, never bothers to find out what it is. The dismissive nickname he uses instead comes from the officer’s tentative offer of his assistance, in exchange for inclusion in the acknowledgements of Ellison’s new book: in the past, he notes, Ellison has always, “Thanked Deputy So-and-So from the local police department.”

The deal done, Ellison puts the deputy on the track of the other murder cases—the Millers in St Louis, and the as-yet unidentified family who were burned to death.

Alone again, Ellison puts on an old recording of himself being interviewed on a talk show about Kentucky Blood, swilling booze while he looks back ten years at himself at the height of his success: as his younger, even smarmier self insists that, “I’m driven by a sense of injustice”, and that, “I’d rather cut my hands off than write a book for fame or money…”

…but be that as it may, we next find Ellison in the here-and-now studying his digital photos of the drawings from the projector-box, and noting in each the position of “Mr Boogie”—including that in the Pool Party ’66 drawing, the artist has positioned him where Ellison saw that spectral figure, in the pool. He begins examining the digital copies of the films and, sure enough, in each one that same figure is present. From BBQ ’79, Ellison manages to capture a fairly clear digital image of the figure’s face.

Ellison receives a call from Deputy So-and-So, who has identified the car victims as the Martinez family from Sacramento—and learned that again, following the murders a child was missing. Ellison is so distracted by these new discoveries that he does not see the image of “Mr Boogie”, still open on his computer, turn and look at him…

(At the time this seems like just a cheesy jump-moment, but to Sinister’s credit it turns out to be something much more significant.)

Ellison’s next discovery is that after scanning the drawings when he found them in the attic, he left his camera-phone still recording, and inadvertently filmed his own fall through the floor—and as that footage plays back now, Ellison sees himself clutched at and pulled down by small, spectral hands…

Speaking for myself, that would be the point where I packed up my family and got the hell out of Dodge; but for Ellison, it’s just one more reason to go wandering around in the dark. This time the noise that wakes him up, and which he tracks to its source, is the projector, which has been turned back on – or has turned itself back on – and is showing yet again the Stevenson murder; and that the footage is playing simultaneously on his computer. Shutting these down, Ellison is nevertheless drawn to his print of the background of the hanging murders, where a pale face can be seen amongst the bushes at the far side of the yard. Ellison carries the image to the window, lining up the shot with the backyard—

—and looks up to see a pale face peering at him from the bushes.

Does he turn the lights on? He does not. He does, however, permanently arm himself with a baseball-bat…

But a baseball-bat is, alas, not much of a defence against the supernatural, which makes itself ever more ominously present from here on in. I rather admire the way Sinister bites the bullet in this respect. Ellison is profoundly reluctant to accept what is happening, though on some level he knows the truth. The issue isn’t is state of mind, but that, strange as his experiences have been, he is simultaneously literally blind to most of what is going on around him…unless it is captured in some sort of film, some sort of image. But we can see…

…and so can a savage dog that strays into the Oswalts’ yard: a panicky Ellison stands his ground and confronts the snarling animal—which abruptly turns tail and runs off, having seen what’s standing behind him…

(This scene got an embarrassed laugh out of me. When I watch a movie like this – in addition to turning on every damn light in the house – I like to make my cat go upstairs ahead of me afterwards. You know, just in case. I’m a little of ashamed of it, but I do it anyway—while living in fear of the day when she reacts exactly like that dog just did…)

Deputy So-and-So turns up to bring Ellison some case files he’s accessed—but also to have a bit of a showdown, having realised that Ellison’s airy line about “just research” was bullshit: “I know a series of connected murders when I see one.” The deputy is sticking his neck out – deceiving the sheriff, for one thing, knowing how he feels about Ellison – and he wants a bit more in return. Beyond that, though, there’s the painful fact that the unsolved Stevenson murders happened in his home-town…

The deputy is sceptical about the same killer being responsible in all the killings, given the disparate M.O.s and particularly the timeframe of the crimes; but Ellison points out that in each case the families were drugged, that a child was missing, and that the same symbol was found. As to the latter, the deputy suggests that Ellison contact Professor Jonas, the local occult / demonology expert (doesn’t every university have one?); while he takes on the task of tracking down the drowning case, where for all of Ellison’s “research”, the victims are so far unidentified. He agrees to do this somewhat reluctantly though. The deputy, unlike Ellison, can recognise when he’s getting in over his head.

Ellison then settles in to watch the last of the film reels, Lawn Work ’86—in which the murder weapon is a lawn-mower…

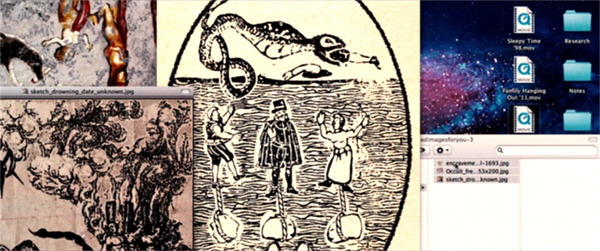

Nevertheless, he does as the deputy suggests and gets in touch with Professor Jonas (an uncredited Vincent D’Onofrio, in an odd, throwaway role). Jonas knows the symbol Ellison has found, and consequently, in his professional capacity, knows the cases he’s investigating, too. He identifies it as the mark of an obscure Babylonian demon: Bughuul, the eater of children.

Though Bughuul himself was an eater of souls, using various tricks to lure his child victims from the physical world into his own realm, Jonas suggests that those committing the crimes may have, in each case, taken a child to be sacrificed, perhaps literally eaten—possibly as a cult initiation.

That night, Ellison is plagued by strange visitations: the projector won’t stay off, and there are noises all over the house…although, unlike us, he can’t see the worst of it. As he prowls around, baseball-bat in hand, he checks the children, finding them safely asleep—he thinks. In fact, though she is motionless, with her back to the door, Ashley is wide awake, staring at the ghostly little girl sitting nearby in the corner of the room, a finger pressed to her lips for silence. And on the wall is a new painting, another rendering of the Stevenson murders, with “Mr Boogie” front and centre…

Ellison is by now sufficiently frightened (yeah, you’d think!) to call upon Deputy So-and-So as a friend – exercising that smarm we saw earlier in his TV interview, to the deputy’s evident discomfort – though he doesn’t really tell him what’s going on, just lets it be seen that he’s freaked out by something. Ellison starts probing the Stevensons’ situation—whether there was anything “weird” about them, or if they ever reported anything strange happening, or anything that came out during the investigation?

Again proving himself much smarter than he seems, Deputy So-and-So starts putting two-and-two together, not least in respect of Ellison’s need for someone to confide in—and deduces correctly that Ellison can’t talk to Tracy because he’s withheld the truth about the house from her:

Deputy: “Oh, man. I would not wanna be around for that conversation!”

What follows is fascinating, as the deputy offers an acute and insightful summation of the situation in general, and Ellison in particular, and why he might be “seeing things”: that the investigation is much darker than he anticipated, that he has put himself under so much pressure, so many different stresses, at the same time that he’s cut himself off from Tracy, that’s he’s drinking heavily, that’s it’s all messing with his head—

(Ellison keeps trying to interrupt, leading the deputy to assure him soothingly, “I don’t think you’re making this up to get attention.” He’s got that far in his reading of Ellison, then.)

Clearly, Ellison is looking for reassurance here—reassurance that whatever he thinks he’s experiencing, it can’t really be that: there has to be the traditional “logical explanation”. To our surprise, it turns he’s brought his goods to the wrong sale. As an opening gambit, he remarks that, of course, the deputy doesn’t believe in “any of that other-wordly stuff”, right? The deputy gives him an incredulous look:

Deputy: “Are you kidding me? I believe in all that stuff. I wouldn’t sleep one night in this place! Are you nuts?”

“Sorry,” he adds lamely, as he sees the effect of his words; pointing out that, just because he believes those things, it doesn’t mean that is what’s going on; and advising Ellison to get out of the house and clear his head.

Ellison is thus left distinctly unreassured, but he hasn’t time to think about it, as Tracy starts yelling for him (she’s the kind of parent who likes to lead with, “Your son did this” and “Your daughter did that”). This time it’s Ashley in the wrong, having violated the rule about painting only on her own walls and decorated the hall with a picture of a girl on a tyre-swing.

(—what is it with tyre-swings lately!?—)

An appalled Ellison recognises the image: it’s the missing Stephanie Stevenson, as seen during the misleadingly benign opening of Family Hanging Out ’11. Ashley explains that Stephanie didn’t want the picture in Ashley’s bedroom, because that used to be her brother’s room; Stephanie, she amplifies for her bewildered mother’s sake, is the girl who used to live in the house; who Daddy is writing about.

And that is how Tracy finds out they’re living in The Murder House.

And, oh, Ellison, you class act:

Ellison: “Don’t blame me; you didn’t want to know!… You asked me if we were living two houses down from a crime scene… It’s not like we’re sleeping where somebody was killed… It didn’t happen here, it happened in the backyard!…”

Tracy, goaded to breaking point, finally calls him out on his selfishness and reckless disregard; though in the long run she gets forgiving much too soon, when she finds Ellison asleep in front of yet another recorded interview: the inevitable one where he explains how family means more to him than success. You know, just like justice does…

But even now Ellison holds grimly on—at least until the spectral forces within the house finally reveal themselves to him. More noises lead him up to the attic, where he finds a gathering of the missing children, all with a finger pressed to their lips for silence, all watching a film featuring Mr Boogie—who then puts in an appearance in person…

Ellison’s rough and ready descent from the attic is followed by the projector and the films, all tossed down after him. After a frozen interval of blind terror, he snatches up the items, rushes to the backyard, douses them in petrol and watches them burn… Tracy, only half-awake, staggers out to catch the end of this and learns that her husband has had an abrupt volte-face, as he bellows at her to get the children ready to leave—now.

Their departure is at such high speed, in fact, that they are pulled over—by Ellison’s old friend, the sheriff. However, hearing that they’re leaving – and not coming back – he tears up the ticket and sends them on their way…

Their old house hasn’t sold yet, so at least the Oswalts have a refuge. (Where they do not turn the lights on. There’s one daytime shot here that, in context, is almost blinding; but then it’s business as usual.) Ellison has already promised Tracy that there won’t be any book and, once they’re back in their old home, he tries to destroy all connection with the Stevenson case, but of course it’s not that easy: for one thing, there are now more people involved.

Deputy So-and-So, for one, who keeps calling—and whose calls Ellison keeps refusing. Professor Jonas, for another, who sends scans of some of the few surviving historical images to do with Bughuul, and which connect the demon with certain animals: a scorpion, a snake, a dog; while each of them contains the symbol found at the crime scenes.

In the wake of this, Ellison does contact Jonas again, who tells him that he has discovered the key detail to the story of Bughuul. Images of him are rare because the early Christians tried to destroy them all—it being their belief that Bughuul lived in the images themselves, which acted as the gateway between the real world and his world; and further, that anyone who saw those images became vulnerable to the demon—particularly children, who might be possessed or abducted.

Clinging to the thought that he has destroyed the film reels and their images of Bughuul, Ellison again tries to put the matter behind him and works on getting the house set up again, including taking stuff to the attic—where sits a familiar grey box. Drawn to it against his will, Ellison discovers something different this time, something extra—literally: an envelope marked Extended Cut Endings.

And in spite of everything, Ellison can’t help himself: he sets up the projector once again. And this time he can see exactly who is committing the murders…

But, prior to this, while he’s still setting up, he finally gives in and takes the call of the frantic Deputy So-and-So, who has discovered the connection between all the murders—a discovery that “researcher” Ellison was on the brink of making himself much earlier – perhaps even in time – except that he got distracted and never went back to it.

It’s that each murdered family once lived in the house occupied by the previous victims – that each of them, in fact, lived for a time in a Murder House – but were not killed themselves until after they moved out…

Sinister is one of those films that’s good, but could and should have been better; possibly I’ve been harder on it than it really deserves, out of a certain exasperation. It’s clever, it’s creepy, and it uses the film set-up brilliantly; but it also skimps at the level of character, which leaves the viewer having to get past the issues this creates.

On the other hand, there is Deputy So-and-So.

(And yes, I know about him and Sinister 2, but that’s all I know, so please keep it to yourselves!)

The film’s score is also very disturbing, though I found it oddly used at times, where it is unclear whether it is meant to be diegetic or non-diegetic: it tends to start up when the film starts rolling, yet clearly isn’t tied to it, which can be disconcerting. Still, as a collection of unnerving noises, it could hardly be more effective—even though the film does resort to the loud-noise-at-scary-moment tactic more intrusively than needed. I’m ambivalent about Scott Derrickson’s use of darkness and the frame, which works well when he uses it; but there are so many of these sequences that turn out to be empty that it gets a little tiresome. I suspect this approach will impact negatively on the film’s re-watch value; there are too many times when the viewer knows that “nothing really happens here”. I’m also a bit over spectral children as a film’s main scare-centre, though Sinister is effective in the deployment of its tiny terrors.

As for the workings of Bughuul and the “transmission”, so to speak, of the murders— Yes, it’s clever, but it’s also full of holes: some intentional, I believe, but a few too many otherwise for comfort and credibility. This is particularly so with respect to the propagation of the images of Bughuul. Ellison Oswalt might expose himself and his family to this material, but such a situation is hardly the norm—so how does it usually work?

Sinister is a fridge-logic film in this respect, leaving the viewer with a whole raft of, “Yes, but—” questions. However, I should stress that it earns its fridge-logic badge honestly, in that these things probably won’t occur to you until after you’ve watched the movie—and calmed down again.

The biggest question I was left with is not a hole, as such, but rather something that occurred to me while pondering the use of The Murder House in this film, and the dynamics of the murder sequence. The gap of a decade or so between killings is interesting—does it imply that there is usually a delay before The Murder House is occupied again (understandably: angels fear to tread where Ellison Oswalt rushes in), or that the eventual victims are allowed to live out their tenancy in peace, despite what happens after they move? What happens if they don’t go?…but then, I imagine Bughuul would find a way to encourage that…

In the end, though, what most caught my attention was the implication that the murders only can and only will happen to families with children. We never learn the full histories of The Murder Houses: does there have to be more than one child in the family?—there always is, but is it necessary?

And what happens if someone childless moves in? Does it break the sequence? Or do the murders just have to wait until the next set of tenants? Are childless people automatically safe, because they have nothing Bughuul wants?

There are plenty of films that deal with the dangers associated with a particular child; less that dare to suggest parenthood in general might be a catalyst for disaster. Sinister leaves us to ponder this uncomfortable point. We may deplore Ellison’s recklessness and the danger it brings down upon his family; but at the same time we should note that there is no reason to think that the earlier occupants of a Murder House did anything in particular to bring Bughuul down upon themselves. Indeed, in the case of the Stevensons, it is specifically denied. As far as we can tell, these families were guilty of nothing but fitting the classic demographic—mother, father, and two-to-three children.

And while we can’t tell if Scott Derrickson actually intended this as a pot-shot at the traditional Norman Rockwell-esque fantasies of domestic bliss and the nuclear family, it is possible to see this film – closing one eye helps – as an ode to childlessness.

************************************************************************************

This review was part of the B-Masters’ THE BAD PLACE Roundtable.

Pingback: Boogie Wonderland « The B-Masters Cabal

It’s an odd divide in horror – the “you deserve it” versus “you were just in the wrong place at the wrong time”. Particularly when one has to try to decode what a filmmaker may have thought “deserved it”.

LikeLike

That’s the thing about horror movies—and disaster movies even more: they like to serve up a mixture of tragedy and Schadenfreude. There will always be undeserving victims, but they tend to make a point of punishing the person who “deserves it”, too; they’re much more satisfactory in that regard than reality.

There’s just a hint in Sinister that something in the parent-child relationship may be necessary for the resulting tragedies – a perceived “deservingness”, if you like – but there’s not enough evidence to be sure about that.

LikeLike

I was wondering if any of the B-Masters would get to Sinister. Have you listened to the commentaries? They are some of the best I’ve ever heard. It’s been a while since I’ve listened to them, but the writer and director sound like huge horror fans, gorehounds even; it’s hard to imagine they’re criticizing horror fans with Sinister. Maybe I should listen again for their exact words.

LikeLike

It was a very late decision, but I’m glad I made it. I’m quite out of the modern horror loop (got a lot of catching up to do!), but I happened to read something about this while I was working on the Amityville films, and got interested.

I wouldn’t say for certain that criticism was intended – it was just a “whiff” I got, if I can put it like that. But then, the film’s so embedded in Ellison’s consciousness that I guess it can criticise him without criticising us. 🙂

No, I prefer not to listen to commentaries when I first watch a film, so they don’t influence my own reaction. I may come back to this one, since you recommend it. I certainly appreciate the film’s pedigree—it’s encouraging that we have these subsets of horror-makers out there at the moment who love their work and don’t feel like they’re slumming or need to apologise for it.

LikeLike

That’s understandable. I wonder if there are people out there who insist on watching commentaries on their first viewing? These commentaries go into some amusing stories such as Ethan Hawke getting a Eureka! moment on what makes horror work (he wasn’t a horror fan at all until working on Sinister) and James Ransone declaring that he gets to play the smartest character in the picture.

OK; it would be interesting to see how much this sort of criticism shows up unintentionally due to not thinking the story out enough. Your idea about the protagonist being a documentary maker instead of a writer is particularly interesting for a story like this and I hope someone does something good with that. One of the commentaries does point out that Oswalt brings everything down on himself; I wonder if they thought that making him less sympathetic would make him less believable or at least more alienating? He struck me as a “believable” sort of unlikable.

I really like that you started with this one. I hope you find some newer films that you really enjoy (or at least provide the basis for epic rants).

LikeLike

I do enjoy a good rant. 🙂

I certainly know people who will work their way through everything on a DVD. For myself, I want that immediate reaction and not to be persuaded out of my opinion (seeing what they meant to do, instead of what they did do).

The trouble with people like Oswalt is that bring things down on others too, and that’s the point I think the film’s a bit mealy-mouthed about. Not from his perspective – maybe he really can’t or won’t see how much damage he’s causing – but his family’s, which I don’t think is well articulated.

Anyhoo— Yes, there’s A LOT out there I’d like to take a look at, but at the moment I’ll just have to add it to my Stuff I’m Going To Get Around To Watching Someday list.

LikeLike

It would be physically impossible for small children to overpower their parents, tie them up and move them into position in front of the cameras, not to mention coming up with murder methods like using another branch as a counterweight when hanging them from a tree. I don’t see Mr Boogie as ‘eating’ the surviving children, but taking them into his world, which could be interpreted as giving them a kind of immortality as a reward for killing their families..

LikeLike

Hi, Sandra!

Well, the families are drugged rather than overpowered, though your point is still valid—clearly the children are being used, rather than doing these things under their own power. We can interpret “soul-eating” however we choose. I’m still interested in the choice of one child out of a family and suspect that a parent-child estrangement is somehow necessary—opening a door for Mr Boogie, perhaps?

LikeLike

I just wanted to say I’m glad to see you back! Any chance Test-Tube Woman will make a return?

LikeLike

Thanks! Embryo, do you mean? – if so, oh yes, it will definitely be back…one of these days…

LikeLike

Hi-

I rented this movie a couple of weeks ago after I read your great review–it’s not my favorite kind of horror movie, but the review got me interested. The thing that haunted me afterwards wasn’t the idea of spooky little ghost children roaming the darkened hallways of my house, but I lay awake that night and, like Sandra above, pondered the logistics of the various murders. Considering the ages and sizes of some of the kids involved, I’m sure that Mr. Boogie had to have lent a hand.

LikeLike

Hi, Kathryn – thanks! Yes, like you, I’m sure he’s working through them. Personally I’m still pondering the question of how he gains control of the children, and why only one child. I think it’s something more than just the images—perhaps that they need to surrender psychological control before he can have physical control?

LikeLike

I assumed early on that Ellison’s daughter would be involved because she was the artistic one who created her own images; the only thing we know about the son is that he screams at night and hides in cardboard boxes. But we never get enough information about the other families to detect a pattern.

One of the little things I really liked in this movie was the old-fashioned images of families murdered long ago. Someone in the movie’s production staff did a good job to make them look authentic. I’m especially fond of the unconcerned-looking man being drowned in the circa-1600 woodcut.

LikeLike

I agree – I think the Super-8 stuff and the other visuals are brilliantly done and very clever.

I guess as far as the kids go, horror movies have taught us to “expect” someone to be attacked through their dreams. I think Trevor’s night terrors, along with his overt curiosity about his father’s work, is a nice bluff to disguise where the real vulnerable point is.

LikeLike

“it being their belief that Bughuul lived in the images themselves”

This kind of relates to why some religions forbid graven images of God, because worshippers might come to think of the graven image *as* God, not just an image of same, might pray DIRECTLY to the idols instead of using them as sort of a focal point for prayers. OSLT, please, don’t anyone quote me. 😐

LikeLike

No, you’re right – I think most cultures and religions in some way acknowledge the power of the image, and Sinister uses that quite cleverly.

LikeLike

Oh, cool, thanks. 🙂

The concept may be at the base of the Second Commandment: “Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven image.” On a related note, although the First Commandment says “Thou shalt have no other gods before me,” few people seem to notice the implication that having other gods AFTER God is, it would seem, perfectly okay…

LikeLike

That’s true, but it isn’t only a Judeo-Christian thing: for example, our indigenous people have a taboo against looking at images of people who have died. Many documentaries, museum exhibits, etc., here carry a warning so that the taboo isn’t accidentally violated.

Perhaps it didn’t occur to God that after Him, people would want any other? Funny how He doesn’t really seem to understand the people He made… 😀

LikeLike

that reminds me – one of those spooky tv shows (maybe the Dark Side, which had one of the all-time great introductions) had one episode where someone develops film from a long-ago expedition, and warriors from a long-lost tribe literally leap off the photos. The heroine saves the day by taking pictures of them, and trapping them on the film again.

LikeLike

After being disappointed by so many modern horror movies (note to James Wan: old woman ghosts in white makeup aren’t that scary, no matter how close you put the camera to them) this one actually impressed me with the level of disturbing imagery. Yes, so the characters aren’t particularly sympathetic or logical, but there’s enough attention to detail in the setup and the frankly nightmarish videos (oh man, the soundtrack to the BBQ one…) that it does legitimately shock.

The two other major issues I had were the creepy-child-acts-creepy schtick with the shhh gestures, and the bane of all horror moviegoers these days, the final lingering shot punctuated by the big bad’s face popping up for a final cat scare, regardless of whether it made sense or not. Other than that though, it was a solid horror with some really uncomfortable scenes.

LikeLike

Hi – welcome! Yes, as I suggested, this is the kind of film that has so much going for it, those points where it takes a soft or lazy option are doubly disappointing; you tend to be harder on this film than you are on lesser ones just because it does so much right overall.

Heh! – I haven’t ventured into James Wan yet, though this isn’t the first complaint along those lines I’ve heard. Though knowing myself, old women ghosts in white makeup will probably work on me just fine… 😀

Actually, I have a plan for getting back into the modern-horror loop and have vaguely tagged Dead Silence as a likely starting point, so we’ll probably find out for sure sooner rather than later.

LikeLike

I was getting some real cognitive dissonance reading this – I was thinking “I saw the trailers for this and it looked horrible! Could it really be fairly good? Did they mess up the trailers THAT bad?” Then I noticed the release date and thought “Isn’t this a fairly recent film?…” Yes, I was confusing it with the sequel which by many accounts truly is terrible. I have to wonder what a Babylonian demon is doing in the U.S.: It’s not like there’s been a shortage of terror and death to feed upon in its home town lately. From your description of Ethan Hawke’s character it sounds like he finally managed to play a more reprehensible person than he did in Reality Bites though, so that’s quite an accomplishment. I’m also rather charmed by the way the Babylonian demon seems to be a hipster – sticking with that old school Super-8 and keeping it real!

Thank you so much for the

LikeLike

I’m sorry to hear that about the sequel—I am planning on watching it so I’ve been avoiding reading anything about it. Still, I like plenty of things that are “generally” criticised so I shall keep hoping.

As Pazuzu taught us, demons go wherever they need to, to get the job done. And where are people more obsessed with filming themselves and watching themselves than the US of A?? 😀 Conversely, I don’t imagine modern Babylonians are much into home movies.

As for Bughuul’s medium of choice, it is beyond reproach! (And jokes aside, terrifyingly effective…)

LikeLike

I have to wonder how Mr Boogie learned to use a camera, then edit the films. Did UCLA film school have a really weird student once ?

LikeLike

It isn’t him behind the camera… 🙂

The suggestion that all forms of human visual communication, from cave paintings onwards, have always acted as a portal is one of the things I like about this scenario.

LikeLike

Just for the record, your review has a way more kickass re-readability than Sinister has re-watchability. 😉 I also kinda dig the idea that my being, other than my quilldren (the cutest hedgehogs in the Multiverse, though I’m admittedly ever so slightly biased as their adoptive mama), being childless (by choice and medical crap, tho it was my choice first so it’s all good with me) protects me from the malevolent interest of Bughuul. Haha! Suck it, Buggy! 😉 Always love your site and writing. ❤

LikeLike

OMIGODHEDGEHOGS!!!!!!!!!! SQUEEEEEEEEEE!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

Thanks for that! I haven’t actually rewatched it since so I don’t have an opinion on that, but even on a first watch I was aware of too many scenes where nothing actually happens.

Heh! – yeah, I’m good with my fur babies so he can suck that too. 😀

LikeLike