“If there’s one thing I wouldn’t want to be twice, zombies is both of them!”

Director: Jean Yarbrough

Starring: Mantan Moreland, John Archer, Dick Purcell, Henry Victor, Joan Woodbury, Marguerite Whitten, Leigh Whipper, Madame Sul-Te-Wan, Patricia Stacey, Laurence Criner

Screenplay: Edmund Kelso

Synopsis: Pilot James McCarthy (Dick Purcell) flies with his passengers, Secret Service agent Bill Summers (John Archer), and Archer’s manservant, Jefferson “Jeff” Jackson (Mantan Moreland), towards the Bahamas. McCarthy and Summers are in search of a plane that was carrying Admiral Wainwright (Guy Usher), now missing for a week. However, McCarthy soon finds his own plane in difficulties due to the violent weather. Off-course and with fuel getting low, McCarthy radios desperately, and finally picks up a broadcast in a foreign language. Although he cannot understand what is being said, McCarthy realises that the signal’s broadcast point must be the immediately below them and determines to try and land in what looks like a clearing. The plane is badly damaged, but the three passengers are unhurt—though startled to find themselves in a graveyard, and surrounded by the sound of native drums. Following the sound, the three find a mansion-house, where they are greeted by Dr Miklos Sangre (Henry Victor), a political refugee from Austria. Sangre orders his butler, Momba (Leigh Whipper), to have the men’s bags collected, while he invites his visitors to the library for a drink. As the men talk, Sangre denies it was his radio broadcast that McCarthy picked up, adding that he has no radio, nor indeed any electricity. He also tells his dismayed houseguests that it may be a fortnight before a boat comes to the island. Sangre has rooms prepared for Summers and McCarthy, but insists upon Jeff sleeping in the servants’ quarters, in spite of his reluctance to be separated from his companions. As soon as Sangre has left their room, Summers and McCarthy discuss their mutual suspicions of him. Meanwhile, in the kitchen, Jeff meets Tahama (Madame Sul-Te-Wan), the cook, and Samantha (Marguerite Whitten), the maid—the latter sending Jeff into a fit of terror by not merely warning him about the island’s zombies, but by summoning two of them by clapping her hands… Jeff carries his tale of zombies to Summers and McCarthy, who scoff; while Sangre insists upon everyone going to the kitchen, to see for themselves that nothing is wrong. Samantha earns Jeff’s indignation by insisting she doesn’t know what he’s talking about—and certainly knows nothing about zombies—while Tahama suggests that Jeff’s sampling of her “brew” might be to blame. Jeff is left behind to fume, while Sangre takes the others back upstairs and introduces them to his wife, Alyce (Patricia Stacey), who is suffering from a strange ailment that keeps her in an almost somnambulistic state. The visitors also meet Madame Sangre’s niece, Barbara Winslow (Joan Woodbury), who they discover is torn between her concern for her aunt and her longing to get off the island. Downstairs, Jeff is horrified to learn that he is expected to sleep in the kitchen—and further unnerved by Tahama’s cackling, and Momba’s warning to pay no attention to anything he sees or hears. Jeff tries to follow instructions—but ends up running for his life as two zombies come stalking towards him out of the darkness…

Comments: On the whole, zombies were not well treated during their first cinematic incarnation. After an encouraging start with White Zombie, which at least tried to make zombie-ism mysterious and creepy, the new sub-genre took a dishearteningly rapid slide into the perfunctory and pointless, with the creation of zombies increasingly trivialised and the end product swiftly relegated to second-, third-, even fourth-banana-dom. Worst of all, it took only three films for the zombies to find themselves transformed from figures of genuine horror to disposable props in a horror-comedy.

But its misuse of its zombies is only one of the sins committed by King Of The Zombies, which offers a challenge to modern viewers—or at least, I hope it does—by basing far too much of its comedy around the “cowardly darkie” stereotype, with Manton Moreland spending much of his screen-time bugging his eyes, shrieking in fright and running around in a state of panic. The often degrading deployment of black actors at this time and earlier tends to set up a kind of cognitive dissonance in the viewer, with awareness of the social and economic realities of the time – best and most succinctly summed up by Hattie McDaniel in the wake of Gone With The Wind: “I’d rather play a maid than be a maid” – jostling against an unavoidable feeling of embarrassment.

But—in fairness to Monogram Pictures, the producers of King Of The Zombies (yeesh – fancy having to be fair to Monogram!), there is more to Manton Moreland’s performance in this film than immediately meets the eye. Yes, the cowardly darkie shtick is there, inarguably; but that’s not all that’s there. This is something that I’ve noticed in other films from time to time—a sense that the degrading stuff had to be included as a cover for what the film-makers really wanted to do.

Here, Moreland’s Jeff is surely the mouthiest manservant who ever managed, somehow, to hold onto a job, never hesitating to speak his mind to the white characters, to the point of being downright rude. Don’t get me wrong – we’re not exactly in, “They call me MISTER TIBBS!” territory here – but you can imagine black audiences of the 1940s reacting to Moreland’s back-talk in something of the same way. And, of course, Jeff is always right; it is his white employers’ refusal to take him seriously that puts their lives in danger, more fools they.

In fact, behind its wince-worthy smokescreen King Of The Zombies does curiously well by its black cast members. I guarantee you this: five minutes after you’ve watched this film, you’ll have forgotten every single thing about the white characters. Whatever memories you do carry away will certainly be centred in Leigh Whipper as the world’s creepiest butler, Madame Sul-Te-Wan as the cackling “Voodoo High Priestess”, Marguerite Whitten as the obligatory sassy maid—or, for good or ill, in Manton Moreland.

Even aside from the racial implications, I have to say that I don’t much care for Moreland’s brand of humour; just not my thing. As a point of contemporary comparison, I don’t much care for Abbott and Costello, either. But, in both cases, there are plenty of people who do; and those individuals will probably get more enjoyment out of King Of The Zombies than I was able to. On the other hand, I do get a kick out of the other three main black characters, particularly Leigh Whipper’s Momba.

Over the credits of King Of The Zombies plays a drum-dominated score that – believe it or not – wound up with an Academy Award nomination in 1942. Back then the category was still “open”, so you often found up to a dozen or more films nominated for Best Original Score. Consequently, for a few brief, glorious moments, King Of The Zombies stood shoulder-to-shoulder with Citizen Kane, How Green Was My Valley, Sergeant York, Suspicion and The Little Foxes, among others…and like them, it lost to Bernard Hermann’s score for All That Money Can Buy. The score of King Of The Zombies was by Edward J. Kay, who would somehow garner four more Oscar nominations over the course of his career, despite never breaking out of the B-movie ghetto. (Let’s put it this way: King Of The Zombies is his nominated film that you’ve heard of…)

King Of The Zombies opens in a plane “somewhere between Cuba and Puerto Rico”. Typically for a Monogram film, it never really gets around to telling us who its characters are; though eventually we deduce that James McCarthy is a military pilot, and Bill Summers some sort of government agent, possibly with the secret service. None of which explains: (i) why a secret service operative has a valet; (ii) why he brings him along on his missions; and (iii) why he discusses presumably classified matters with him (or at least in front of him). By all of which you will deduce that the third passenger in the plane is Jefferson Jackson, Esquire.

McCarthy and Summers are searching for the downed plane of one Admiral Wainwright, but soon find themselves in difficulties of their own—off-course, no radio contact, and running out of fuel. Unexpectedly, McCarthy picks up a signal on his radio—thus introducing one of this film’s most bewildering touches, as McCarthy declares a language that is clearly German to be, “A new lingo to me; I don’t understand it.”

My own theory is that this was Monogram Pictures thumbing its nose at the authorities. In the pre-war era, with the US maintaining a dogged neutrality, various film-makers attracted official wrath with productions like Confessions Of A Nazi Spy and The Mortal Storm, which steadfastly refused to look the other way; there was also the nauseating spectacle of officialdom trying to placate Mussolini over the production of Idiot’s Delight.

While this attitude may have been understandable pre-1939, it is astonishing – and rather disgusting – to consider that as late as May 1941, the authorities may still have been pursuing a policy of “don’t insult the Germans”; but it is difficult to interpret this bit of business over the “unrecognisable language” any other way than Monogram being warned against making their villain too overtly a Nazi and responding with some healthy disrespect, obeying the dictum in a way that made it even more ridiculous than it inherently was.

McCarthy announces that the radio emitting the broadcast must be immediately below the plane, and drops altitude to see. There is indeed an island down there and, spotting a clearing, McCarthy decides on an emergency landing, which goes better than anticipated thanks to some astonishingly fragile trees—they get cut in half, rather than smashing the plane’s wings. Consequently, the three plane-crash survivors have nothing worse than a cut on the forehead between them.

The clearing that McCarthy saw from the air turns out to be a cemetery, allowing for the first of many panic attacks by Jeff; one exacerbated by the sight of what he takes to be a ghost, but which turns out to be McCarthy struggling under a parachute. (How he got there is a mystery.) Summers hurries over and helps McCarthy up, exclaiming in surprise, when he spots the forehead cut, “Hey, you’re hurt!” Yeah, fancy getting hurt in a plane crash!?

Concluding both from the sound of drums and the presence of what appears (on the basis of its dates) to be an operational graveyard, that someone must be in the vicinity, the three walk through “the jungle” – all of about fifty metres – and spot a mansion-house. There is no immediate answer to their ring of the bell, but the door is open, so they walk into the darkened premises—and find themselves confronted by a man carrying a candle, who eyes them suspiciously, but then says politely enough, with a formal bow, “Welcome to my humble home.”

Alas, alas, what could have been! King Of The Zombies was the second directorial effort of Jean Yarbrough, who the previous year had helmed The Devil Bat for PRC, Monogram’s main rival: a wonderful piece of nonsense highlighted by Bela Lugosi’s performance as “kindly Dr Carruthers”, friendly neighbourhood mad scientist. Yarbrough wanted Lugosi for King Of The Zombies, too, but he was unavailable (possibly because of his involvement in PRC’s mindboggling The Invisible Ghost). Negotiations with Peter Lorre then fell through; and at the last moment Henry Victor accepted the role.

Unfortunately for resulting production, Victor hasn’t the kind of idiosyncratic personality that either of the others would have brought to the role of Dr Miklos Sangre, which leaves a void at the heart of a film already struggling to hold the viewer’s attention. On the other hand, it is weirdly apparent that Jean Yarbrough’s direction to Victor amounted to, “Do your best Lugosi”—the actor delivers his dialogue in a stilted manner that mimics Lugosi’s own speech patterns. It’s a nice try, but really, it only serves to remind the audience of what they’re missing.

Summers starts to explain their presence, but Dr Sangre interrupts to comment that he already knows. The others are startled by this, with Sangre adding mysteriously, “Very little happens on this island that I do not know about.” The implication seems to be that he got the news via jungle telegraph, though I wouldn’t have thought that necessary for a plane crash a few yards from the front door. Sangre calls his butler, Momba, and orders rooms prepared for his guests, inviting them into his library for a drink in the meantime. Jeff tries in a hurried under-voice to convince Summers that, “Something’s wrong here”, only for his fears to be dismissed for the first but by no means the last time by his employer. Sangre then takes notice of the cut on McCarthy’s forehead, insisting on treating it as, “On this island, the slightest injury may prove fatal”, on account of the climate and the evil spirits, “Who prey on the injured.”

A weird little interlude follows, with Sangre denying Jeff a drink and then banishing him to the servants’ quarters: behaviour that, in-film, marks Sangre as the Big Bad, but which surely, out of film, was exactly what a black servant could expect? We also note that when the hopeful Jeff reaches for a brandy, McCarthy gives him a dirty look; while Summers seems to find his discomfiture amusing. In other words—the American good guys treat Jeff every bit as badly as the Nazi villain. What are we supposed to make of that?

Summers goes on to explain their arrival on the island, only for Sangre to hurriedly insist that it was not his broadcast they picked up. It could not have been—because there is no radio on the island—because there is no electricity—because there is no generator.

As soon as they are left alone, Summers and McCarthy have a hurried conference. The latter is certain that the broadcast did come from this island; and, moreover, when Sangre spoke to Momba, “It was the same blather we heard on the radio.”

Downstairs, Jeff is further unnerved by Tahama, the cook, but brightens upon being introduced to Samantha, the maid. The latter tells him matter-of-factly that the island is crawling with evil spirits—“And just wait’ll you see the zombies!”—elaborating that zombies are, “Dead folks, what walks around”—a definition sadly disproved by the film itself. Be that as it may, Samantha further informs Jeff that zombies may be summoned just by clapping your hands, and proceeds to prove it. The subsequent encounter sends Jeff rushing upstairs in a state of shrieking panic.

The white folks scoff, of course; Sangre in particular seems amused, and insists on going down to the kitchen to see for himself. No zombies are in evidence, and Samantha earns Jeff’s indignation by blandly denying all knowledge—with the cackling Tahama suggesting that Jeff’s sampling of her “brew” might be responsible for this interlude. Once the bosses are gone, Jeff takes Samantha to task, and has the satisfaction of forcing her to admit the truth, when she hurriedly stops him clapping his hands.

And for all Mantan Moreland’s clowning, it is Marguerite Whitten who comes away with the line of the film, thanks to her stylish way with a quintuple negative:

Samantha: “Mister, that’s somethin’ that ain’t never no good for nobody to do no time.”

She also scolds Jeff for being so mouthy in front of Whitey, which he really shouldn’t need telling.

Upstairs, Summers and McCarthy are introduced to Madame Sangre, who is suspiciously unresponsive herself. Sangre explains that he is trying to cure her “malady”, and is moved to wax philosophical:

Sangre: “Here is a peculiar case to that of the zombies, which your servant claims to have seen, where supposedly they are dead yet retain a certain amount of animation. She lives—yet walks in the land of those beyond…”

The final member of the household is introduced via the kind of unexpected moment that often makes these cheapy productions by Monogram so oddly memorable. At any rate, I’m fairly sure that no heroine of a mainstream film of the time would have been presented as a secret tippler! But such is the suggestion made here regarding Barbara Winslow, Sangre’s niece – “By marriage,” she clarifies hurriedly – who is caught sneaking a snifter from the brandy-tray in the library.

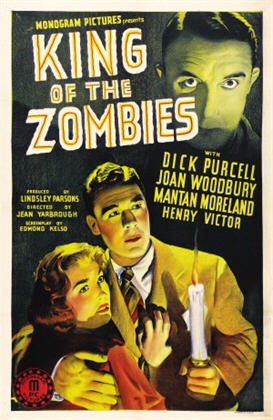

Of course, when I call Barbara Winslow “the heroine” of King Of The Zombies, I really mean that she’s “The Chick”, just there to be clutched on the film’s poster.

Which, by the way, raises another point in King Of The Zombies’ favour: while we’re considering the good, the bad and the ugly with respect to Mantan Moreland, we should note that he was given third billing here, over both John Archer, the film’s putative romantic lead, and Henry Victor, its villain. We might argue that he should have had top billing, but that simply wasn’t going to happen in 1941, or for some time afterwards. Consider 1949’s Home Of The Brave, in which James Edwards is unquestionably “the star”—and which lists its cast in alphabetical order precisely to avoid giving the young black actor billing.

Barbara’s opening remarks betray her longing to escape from her island prison, which in turn prompt Sangre to show a little of the cloven hoof: “None may leave this island as he so chooses!” He covers hurriedly, explaining he only meant himself and his family. They are refugees from Austria, you see, and fled without their passports; so they’re stuck where they are.

Which, if taken at face value, raises far more questions than it answers—like, how did refugees from Austria end up on this island in the first place? And if they’ve only been there a few years, whose graveyard (full of recent dates) is that? And whose house? And how did the servants get there? – not least Samantha, who was for some reason imported “from Alabama”?

Mind you, these faux-mysteries pale in comparison to the question raised by the revelation of what’s really going on: namely, how did an Austrian refugee-cum-Nazi agent end up with so many “native” collaborators, not to mention an alternative career as a voodoo witch-doctor who practises Druid rites? Alas, like so many Monogram films, this one functions as a kind of anti-Soap, in that, “These questions and many others will NOT be answered during the course of King Of The Zombies.”

Sangre’s behaviour has increased the suspicions of his visitors, who start fishing. Summers suggests that this area is bad luck for planes, while McCarthy reveals the disappearance of Wainwright—“One of our ranking admirals.” As opposed to your non-ranking admirals? Summers explains that Wainwright was on his way to Panama, on a mission for the government, which prompts Sangre to start tugging at his collar.

Another odd interlude follows, with McCarthy inspecting Sangre’s collection of artifacts, and Sangre pointing out one in particular that should interest him, as he is “obviously” Irish (it wasn’t obvious to me, but perhaps I was distracted by his grating Brooklyn accent): “The ceremonial mask worn by the ancient Druid high-priests, during the rites of transmigration…the transfer of the soul of the dead to the body of the living.” A brief exchange about lingering superstition in The Old Country follows, which I can only imagine was supposed to justify what happens to McCarthy later in the film.

Eventually everyone heads for bed—with a quaking Jeff ordered to sleep in the kitchen. Sure enough, at the stroke of midnight our two zombie friends come wandering in, setting off another shrieking panic attack and a dash upstairs. A repetition of the earlier scene follows, though leavened on one hand by Jeff’s refusal to be mocked out of his position this time, and on the other by a line that was clearly written to be delivered by Bela, sigh:

Sangre: “Zombies don’t eat…meat.”

But despite Sangre’s attempts to isolate him, Jeff argues his way to a spot on the couch in Summers’ room.

And never mind the zombies: by far the most startling thing in this film is here revealed. Though Sangre had adjoining rooms prepared for Summers and McCarthy, we are now treated to a glimpse of two men getting undressed together; after which, they proceed to share a bed…!?

Bill and Jim? More like Ernie and Bert.

In the middle of the night, a silent female figure comes gliding into the room through a panel in the wall. For a moment it stands over our sleeping love-birds—I mean, our red-blooded heterosexual heroes, and don’t you dare suggest otherwise—and then drops something on the bed before gliding away again. All this a terrified Jeff observes, but of course he doesn’t make a noise until after the apparition has gone, because it’s been at least two minutes since Summers disbelieved him about something. However, this time there’s an earring on the bed to back him up. Summers and McCarthy examine the wall, but can’t find the catch that’s presumably there.

Then the doorknob of their room turns, though when McCarthy dashes into the passage there’s no-one there. The three set out to do some searching. Summers orders Jeff to lead McCarthy to the kitchen, while he takes the library. There, he catches Barbara with a book on hypnotism, which both of them believe to be at the bottom of Madame Sangre’s “malady”. Earlier on, Summers and McCarthy heard what sounded suspiciously like a generator, and now Barbara confirms that Sangre almost certainly has a radio transmitter hidden somewhere.

Downstairs, no zombies are immediately in evidence (it doesn’t occur to Jeff to clap his hands), but of course one shows up as soon as the two men separate. This time – huzzah! – McCarthy arrives in time to see that Jeff’s terrors are justified. He gets knocked down for his trouble, taking a second whack on the head. Summers hurries in, and then Sangre turns up, both in response to Jeff’s wailing. Sangre explains that his servants act as guards during the night. McCarthy shows his disbelief a little too clearly, and Summers hurriedly intervenes, agreeing that of course there’s no such thing as zombies and yes, they should have stayed in their rooms.

A bit of rank stupidity follows. The next morning, Barbara identifies the earring as one of her aunt’s; and indeed, when Madame Sangre is brought in, she proves to be wearing that exact pair. Whuh? “I daresay there’s not another pair like them in the world,” exposits Sangre helpfully, though apparently there is a stray third.

Summers and McCarthy go to inspect the plane, though Sangre intervenes to stop Barbara going with them. Naturally they find that their radio has been sabotaged—too bad McCarthy didn’t go out to guard it when it first crossed his mind to do so, instead of spending the night in bed with Summers getting a good night’s sleep. McCarthy also points out a freshly dug grave in the cemetery, prepared for someone who was already buried a week ago.

Here we learn that Summers remains sceptical on the matter of zombies, despite McCarthy’s conversion. The two men decide to split up (uh-oh!), with McCarthy searching for the generator, and Summers trying to get Barbara away from Sangre long enough to learn what she evidently wants to tell him. McCarthy heads off into the jungle, with two zombies on his tail…

The sound of drums has resumed and, much to our delight, it proves to be emanating from a secret room under the house (again: who built that?) where Sangre – gasp! – conducts his voodoo-Druid rituals—that is, voodoo built around the aforementioned “transmigration of souls”. We learn here that Tahama, for one, is on it; while the target of the ceremony is a dishevelled white guy, none other than the missing Admiral Wainwright.

An impatient Sangre exclaims that Tahama’s magic is too slow – and besides, it has put Wainwright to sleep. Tahama bridles indignantly, proclaiming herself “High Voodoo Priestess”, and insists that she has put Wainwright into a trance, if you don’t mind. “The three men upstairs may be in the secret service!” announces Sangre – what, Jeff too? excellent! – and orders Tahama to hurry up and make Wainwright talk. He then goes to his radio and transmits a message in, ahem, unidentifiable blather.

An extended comedy routine between Jeff and Samantha follows, in which it is suggested that one of the zombies is her very-ex-boyfriend. Summers breaks this up with the revelation that McCarthy is missing; he sends Jeff to collect his gun. Jeff catches Sangre going through Summers’ things—and the one time he should have panicked, shrieked, and run away, he simply lets Sangre lead him through the secret panel and down the hidden staircase…and ends up getting hypnotised into a zombie himself.

Maybe. King Of The Zombies is bewilderingly unclear about its zombies—whether they are undead, as the grave pointed out by McCarthy or Samantha’s amusingly casual claim about her dead boyfriend might suggest; or whether they are simply the living in deep hypnosis, as implied by Barbara’s attempts to bring her aunt out of it.

Sadly, it’s almost certainly just the latter—Sangre’s hypnotism of Jeff involves convincing him that (i) he’s dead; and (ii) he’s a zombie; although this doesn’t really explain why he alone snaps out of it so easily…unless he wasn’t really hypnotised, so much as convinced he was hypnotised. (Also alone of all the zombies, Jeff can still talk…too much to hope for a little silence from Mantan, I suppose…) At any rate, he makes a spontaneous recovery under the influence of very bad zombie-chow – Samantha’s cooking for the living is much better – and his continued existence is confirmed by his ability to eat salt, which Samantha claims will destroy a real zombie. Also, he can see himself in a mirror, which zombies can’t. (Although how Samantha can know all this, unless…)

Meanwhile, we get an hilarious confrontation between Summers and Momba, which Leigh Whipper absolutely steals with his air of well-trained-butler disinterest, underlain with just the faintest hint of contemptuous insolence:

Summers: “What are you doing in here? Where’s Jeff?”

Momba: “I wouldn’t know, sir.”

Summers: “It’s gone! You know about this, you devil! Give me that gun!”

Momba: “I have no gun, sir.”

Summers: “Don’t lie to me!” [pats him down] “Somebody has! Where’s Jeff? And where’s Mac, what’s happened to him?”

Momba: “I wouldn’t know, sir.”

Summers [grabbing him]: “You’re going to tell me, or—”

Momba: “I said, I wouldn’t know, sir.”

Summers [letting go]: “You wouldn’t spill it if you did know. I’m going to find him if I have to search every inch of this island!”

Momba: “Yes, sir.”

Summers’ subsequent search is unavailing – he doesn’t even see the zombie standing three feet from his elbow, so not much chance of him finding McCarthy or Jeff – but when he returns to the house he catches Barbara trying to de-hypnotise her aunt, which for some reason convinces him she’s “in it” with Sangre. They are interrupted by McCarthy, who staggers in near-catatonic. Summers is inclined to blame it all on Barbara (!), whereas Sangre re-inspects the bump on McCarthy’s head and concludes that he has, “Contracted a very rare and dangerous jungle fever.”

(He’s got jungle fever!?)

Sangre adds that McCarthy’s condition is beyond his powers to treat, and King Of The Zombies wins another couple of points by calling in “a native doctor in the village”, who is surprisingly revealed to have been, “Educated in [Summers’] country.” White Man’s Medicine does McCarthy no good, however: according to Dr Couillie, McCarthy is dead—and, what’s more, “Has been dead since morning…”

Summers’ distress at his friend’s bizarre death is added to by a local law insisting on immediate burial—“The climate and – something even worse – makes it necessary,” explains Sangre, most uncomfortingly.

The two are interrupted by Momba – “Moment, bitte,” says Leigh Whipper distinctly. Once alone, however, both Momba and Sangre revert to English (?), with the former telling his master that a radio message has just come through: “they” must have Wainwright’s information at once. Momba then urges “the ceremony”. Sangre agrees that “the rites of transmigration” are the only way, and orders Momba to make the preparations.

Called away from her more mundane duties, Tahama tells Samantha that she’ll have to feed the zombies. The girl protests – apparently that’s not in her job description – but Tahama simply orders her to set another plate for, “The Irishman.” Samantha is a little startled at the thought of “a white zombie”, but otherwise not much bothered by the situation.

There is, however, no immediate sign of McCarthy, undead or otherwise; though both Jeff (newly de-zombified) and Summers fear the worst. A scream leads Jeff and Summers downstairs, where they find both Madame Sangre – really dead, evidently – and McCarthy’s coffin, albeit unoccupied. The sound of drums comes from nearby.

The comic highlight of King Of The Zombies follows – naturally, it’s a scene intended seriously – as Sangre, donning a Druid ceremonial mask, performs the “rite of transmigration”, while all around him natives led by Tahama and Momba do a rather catchy dance-and-chant to the rhythm of voodoo drums.

(As I said re: Sugar Hill— I’m not sure real voodoo ceremonies are that funky.)

The camera then pans across a line-up of zombies, and we see that – gasp! – McCarthy is amongst them.

Summers and Jeff make their way into the “secret” room via a strangely cooperative hidden door and hide (badly). The focus of the ritual is Barbara and Wainwright, who kneel opposite one another, their arms bound. Tahama demands to know who Barbara is, and after some confused hesitation, she answers that her name is Wainwright…

The be-masked Sangre then advances, demanding that “Admiral Wainwright” reveal his orders. Barbara / Wainwright is just about to answer when Summers inadvertently reveals his presence, and Momba interrupts. “Unbelievers!” he gasps—although whether it is voodoo-ism or Nazi-ism that Summers is being accused of not believing in isn’t immediately clear. Sangre rips off his mask and turns to his zombies, ordering, “Get them!”

The zombies stagger forward – led by McCarthy, of course. Summers pleads, “Mac, go back! It’s Bill—Bill Summers—your pal!” Oh, his pal? Is that what they were calling it in 1941? Be that as it may, Zombie-Mac hesitates…and then turns…and leads the other zombies towards Sangre…

The voodoo practitioners flee shrieking, while Sangre orders his white zombie to stop—quite unavailingly, of course. Sangre then whips out a gun and starts shooting, but this achieves nothing either. McCarthy and the other zombies keep moving forward, Sangre keeps backing away…and ends up stumbling into the fire-pit conveniently situated at the far end of the room.

Sooo…the zombies could have rebelled at any time, but didn’t until there was a white guy to show them what to do?

Sigh.

Sangre’s demise evidently releases both Wainwright and Barbara. (Pity: we might otherwise have had America’s first female admiral on our hands.) Wainwright radios for help, and tells the others that a boat will be there is the morning.

Summers, meanwhile, reports that despite all evidence to the contrary, McCarthy is “raring to go”—although, “Those bullets didn’t help him any.” You mean those three bullets fired into his chest at close range? No, one imagines not. Of course, the salient point here is that, even before Sangre started shooting, McCarthy was still alive, despite being declared dead, and being buried.

But naturally the screenplay never bothers to clear up these unimportant plot details. Instead we hear about how Wainwright’s plane was brought down, his crew murdered, and he himself tortured; and how, when that didn’t make him talk, Sangre tried first Tahama’s voodoo powers, and then the rite of transmigration, by which the Admiral’s knowledge was meant to be transferred into a “recipient” (even though it was declaredly a process for transferring a soul)—first Madame Sangre, who “broke under the strain”, then Barbara.

We note in passing the implication that a weak-minded female is necessary for the success of the rite…

But of course, it’s Jeff who gets the final word:

Jeff: “If there’s one thing I wouldn’t want to be twice, zombies is both of them!”

Want a second opinion of King Of The Zombies? Visit 1000 Misspent Hours And Counting.

And a shout out to the French, who had the grace to at least put this film’s star somewhere on their poster.

Doctor Sangre, from Austria… I guess “Doctor Blut” or “Doctor Vér” was considered too subtle.

“Rest in Peace” by Lápida Genérica, for all your anonymous graveyard needs!

I picture a parody version of this with the plane crashed through the living-room wall, like the beginning of the 1980 Flash Gordon, and Sangre saying “very little happens on this island that I do now know about”.

Why should being in someone else’s body make you more easily interrogated? Being hypnotised, sure.

LikeLike

Yeah, “subtlety” is not exactly this film’s middle name. 🙂

I’m sticking with my “weak-minded female” theory…

LikeLike

Pingback: Revenge Of The Zombies (1943) | and you call yourself a scientist!?

Pingback: Association of ideas « The B-Masters Cabal