“I got news for you guys: we just passed the point of no return.”

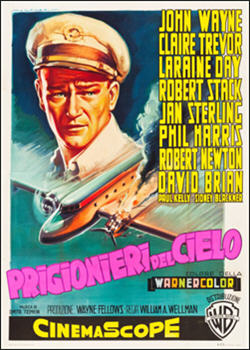

Director: William A. Wellman

Starring: John Wayne, Robert Stack, Doe Avedon, Claire Trevor, Jan Sterling, William Campbell, Wally Brown, Robert Newton, David Brian, Sidney Blackmer, Paul Kelly, John Qualen, Laraine Day, John Howard, Phil Harris, Julie Bishop, Paul Fix, Ann Doran, Karen Sharpe, John Smith, Joy Kim, William Hopper, George Chandler, Douglas Fowley, Regis Toomey, Pedro Gonzales-Gonzales, William Schallert, Michael Wellman

Screenplay: Ernest K. Gann, based upon his novel

Synopsis: After a chance encounter on the tarmac of Honolulu Airport, Crew Chief Ben Sneed (George Chandler) tells his team about Dan Roman (John Wayne), a veteran flyer now employed as a co-pilot by Trans-Orient-Pacific, who years earlier was the sole survivor of a plane crash in South America in which he lost his wife and young son. Inside the airport, TOPAC Agent Alsop (Douglas Fowley) and flight stewardess Miss Spalding (Doe Avedon) check in the passengers of TOPAC flight #420 between Honolulu and San Francisco, while pilot John Sullivan (Robert Stack) and navigator Len Wilby (Wally Brown) work out the flight plan. Second officer Hobie Wheeler (William Campbell) speaks disparagingly of Dan Roman’s age, only to be cold-shouldered by Sullivan. At the last moment, Humphrey Agnew (Sidney Blackmer) rushes up to the ticket desk and buys a seat on the flight, first inquiring whether aviation tycoon Ken Childs (David Brian) is on board. As the plane begins to taxi, Miss Spalding pays special attention to José Locota (John Qualen), an immigrant fisherman who has never flown before, and former businessman Frank Briscoe (Paul Fix), who is terminally ill. Shortly into the flight, Miss Spalding asks Sullivan to reassure one of the passengers, Broadway producer Gustave Pardee (Robert Newton), who is terrified of flying. As Dan Roman takes the controls, a strange vibration ripples through the cockpit; both Roman and Spalding notice, but as the vibration is not repeated neither says anything. In the cabin, as Sullivan moves amongst the passengers, newlyweds Nell (Karen Sharpe) and Milo Buck (John Smith) contemplate the beginning of their life together; Lydia (Laraine Day) and Howard Rice (John Howard) discuss divorce; Clara (Ann Doran) and Ed Joseph (Phil Harris) look back at their long-anticipated but disastrous holiday; physicist Donald Flaherty (Paul Kelly) writhes with self-loathing as he reflects upon his role in the missile program; and Chinese-born Korean immigrant Dorothy Chen (Joy Kim) contemplates her new life in America. Former beauty queen Sally McKee confides her troubles to Sullivan: she is engaged by correspondence, but her fiancé knows her only by an eight-year-old photograph. Meanwhile, faded goodtime girl May Holst (Claire Trevor) makes a move on Ken Childs, as Humphrey Agnew watches in growing agitation, fondling the gun hidden in his pocket… Later, Sullivan takes a break and lies down in the pilots’ rest area. The loquacious Len Wilby begins telling Sullivan all about his much-younger wife, Sally, but Sullivan isn’t listening: he is too busy recognising his own growing case of nervous tension. Suddenly, Sullivan becomes convinced that the plane’s propellers are out of sync; Roman and Wheeler check, but find nothing wrong. As the flight proceeds, both Roman and Wilby notice that Sullivan is not himself, but is jittery and short-tempered. In the galley, Miss Spalding notices another vibration, and this time reports it to the cockpit. She finds that the crew is aware of a problem, but cannot locate it. Wheeler radios San Francisco, as Wilby reports that the plane has passed the point of no return. Back in the cabin, Agnew finally makes his move, threatening Childs with his gun while accusing him of having an affair with his wife. The other passengers react swiftly, wrestling the gun away from Agnew and restraining him. At that moment, the plane lurches violently, and Sally McKee shrieks that one of the engines is on fire…

Comments: The early days of commercial air travel were both exciting and dangerous, with the wonder and romance of flight for the average person tempered by the distressing frequency of related disasters. Even before the de Havilland Comet crashes that plagued jet aviation in Britain in the early fifties, American piston-powered airliners were suffering a similar fate, with crashes occurring so regularly that as early as 1947, Harry S. Truman ordered an inquiry into air safety. As with the Comet crashes, a design flaw was found to be the cause of most of the incidents. Unlike the British experience, however, little finger-pointing and scape-goating accompanied the investigation, probably because while commercial aviation in Britain was a private enterprise, American aviation remained a semi-government entity, which much of its effort geared towards developing new technology for military purposes.

It is not to be wondered at that writers saw the potential for fictional drama in this time of disaster and triumph, nor that a significant number of them had themselves a background in engineering or aviation, with a grasp of both the technical issues and the mindset of the people who designed, built and flew the planes.

Thus from the 1940s through the 1960s, we see publications such as No Highway, by engineer and designer Nevil Shute, whose flight tales comprised his earliest published works; the novel would be filmed in 1951 as No Highway In The Sky. The Take Off, The Proving Flight and Cone Of Silence were written by pilot David Beaty, who would also pen the bluntly factual, Naked Pilot: The Human Factor In Aircraft Accidents, which incredibly was greeted with almost universal hostility within the aviation industry, as if in telling the truth Beaty was guilty of some sort of betrayal. (Subsequently, the study upon which Beaty’s book was based was made a mandatory text for European pilots, and Beaty was awarded an MBE.)

Of a similar breed was Ernest K. Gann, who flew in both World Wars, in between them working as a barnstormer and a stunt pilot before becoming a commercial pilot. Gann’s early long works were non-fiction accounts of his experiences, but his novel writing, too, focussed upon aviation and aviators. Blaze Of Noon, the story of four brothers flying during the early days of air-mail, was filmed in 1947; while Gann’s Island In The Sky, based on the author’s own experiences in searching for a downed plane during WWII, was optioned by the newly-partnered John Wayne and Robert Fellows and produced during 1953.

Island In The Sky starred Wayne as the pilot trying to hold his crew together in an icy wilderness while they wait for rescue; Ernest Gann was hired to adapt his own novel, and William A. Wellman to direct. Wellman himself was another aviator-artist: he joined the Lafayette Flying Corps during WWI and survived being shot down, emerging from the crash with only a limp; after the war, he joined what was then called the US Army Air Service and taught combat pilots. Befriending Douglas Fairbanks, Wellman ended up in Hollywood and had a brief career as an actor before running through a series of off-camera jobs and finally winding up in the director’s chair.

A significant number of Wellman’s films dealt with aviation, from 1927’s Wings through to his last directorial effort, 1958’s Lafayette Escadrille. It was on Wellman’s recommendation that Wayne-Fellows optioned Ernest Gann’s 1952 novel, The High And The Mighty, which had been a smash best-seller. Initially, the role of Dan Roman had been intended for Spencer Tracy, but he pulled out at the last minute, leaving a gaping hole in the production that needed to be filled by a big name. Henry Fonda was offered the part, but declined it. Left with little choice, the Duke stepped in.

So John Wayne was a major player in the development of the modern disaster movie. Who knew?

Of all the genre labels, disaster movie is perhaps the most nebulous. In fact, if you asked me to define “disaster movie” for you, I doubt if I could; instead, I’d probably fall back upon the immortal words of good old Justice Potter Stewart and tell you only that I know one when I see one. Many films feature a disaster, whether it be natural or man-made, without making the grade as a disaster movie. Conversely, disaster movies frequently feature no real disaster at all. Most film labels tell you something about the film’s content and setting, but with “disaster movie”, it’s all about the attitude and the execution. I don’t imagine that anyone connected with The High And The Mighty set out to make a disaster movie, but they did it just the same. The film was an innocent victim of when and why it was made.

By 1954, the battle between cinema and television had been well and truly joined, which had a variety of effects upon movie production, as Hollywood’s attempts to lure people away from that pernicious box in their lounge-rooms became more and more desperate. It was during the early fifties that the first cracks in the Production Code began to appear, not just in the works of outright rebels like Otto Preminger and Stanley Kramer, but in solid studio productions like this.

I once did a film study course on the introduction of CinemaScope, which meant that the class members spent weeks immersed in early fifties cinema; so much so, that when, during the 1954 murder-mystery Black Widow, the line, “By the way, you did know that she was pregnant?” was spoken, there was an audible gasp from many of those present. I can’t say for certain that this was the first onscreen utterance of the word “pregnant” in the Code era, but it was mighty close to it.

Similar moments are present throughout The High And The Mighty. In the novel, newlyweds Nell and Milo Buck, convinced that they’re going to die, join the Mile-High Club; the film implies the same as explicitly as it can. And while Milo doesn’t actually say the word “pregnant”, but he does use the traditional hand gesture, which would also have been out-of-bounds a few years earlier. During his account of the Josephs’ Holiday From Hell, Ed describes an encounter with another couple who clearly have partner-swapping on their minds; this done in dumb-show and treated comedically, which is probably why it was allowed.

Meanwhile, the sexual and alcohol-related misadventures of Sally McKee and Susie Wilby are handled fairly bluntly, while May Holst describes herself as “a broken-down broad.” Like “pregnant”, “broad” was previously a forbidden word under the Production Code. While these touches may seem amusingly tame today, they were a big deal at the time, and are indicative of Hollywood’s recognition of how bloody its battle with television was likely to become.

(Hey, gang! I think it’s time we did our own pre-flight check. don’t you? Let’s see: who have we got here…?)

A more usual approach to the problem of television was for the movies to get progressively bigger and broader and brighter and louder; glorious Technicolor and breathtaking CinemaScope and stereophonic sound, as Cole Porter would put it, as well as innovations such as 3-D, became increasingly common. Indeed, there was initially some talk of making The High And The Mighty in 3-D, but the idea was scrapped quite early on, with the decision made to shoot in CinemaScope instead. (And “WarnerColor”.)

All the advertising for this film was concentrated upon just how BIG a production it was: BIG screen, BIG stars, BIG drama; and indeed, we can see here an early example of what we now consider a standard feature of your textbook disaster movie: the ensemble cast. Just take a look at that poster up above: The High And The Mighty is nothing less than a box picture; not a real box picture, as the actors aren’t identified by a short-hand character summation (“Paul Kelly IS The Drunk, Sidney Blackmer IS The Panicky Idiot”), but the same idea is there, to let the public know what a galaxy of stars they’ll be seeing when they see this film; so many more than they’d ever see together on that tiny television screen. The primary use of CinemaScope here, given that the bulk of the film takes place on one of only two main sets, is simply to get as many members of the cast as possible in shot at the same time.

In truth, a close examination of that poster is revealing in a way that the producers of The High And The Mighty certainly never intended. At its pinnacle, it was of course possible for a disaster movie to co-cast Paul Newman and Steve McQueen and still make an outrageous profit; but for the most part the genre is more accurately represented by the later Irwin Allen productions, full of familiar names but hardly huge stars (“Leslie Nielsen IS The Mayor, Barry Newman IS The Doctor”).

This is also true of The High And The Mighty, although it was not the original intention. Spencer Tracy was not the only established star to give this flick the flick. In fact, there is almost no end to the list of big names that declined to have anything to do with the production. The problem was, they were stars; they didn’t want to be part of an ensemble, just one the crowd. When The High And The Mighty finally began shooting, its only indisputable A-lister was the Duke himself; the rest of the cast was a solid mix of actors on the way down and actors on the way up; the classic disaster movie formula.

The other factor that qualifies The High And The Mighty as a disaster movie is its complete – and I mean complete – lack of subtlety. Much of this may be traced back to Ernest Gann’s novel. Gann was a solid and convincing writer as long as he was dealing with aviation and aviators, but was far less successful away from his main area of interest. Most of the characters in The High And The Mighty are simply stereotypes, but the length of the novel allowed Gann to put at least a little flesh on their bones.

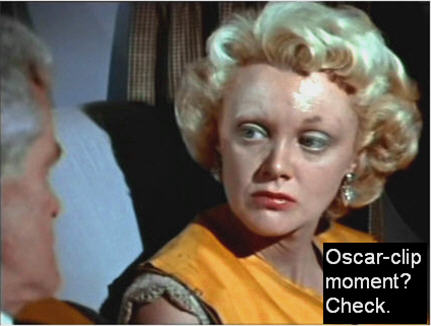

Unfortunately, in cutting down his novel for the screen, Gann ended up slicing that flesh away again, leaving us only with the underlying clichés. The problem is compounded by William Wellman’s approach to this film, in which, evidently in pursuit of the ultimate goal of BIG, he seems to have directed his cast to overact as much as humanly possible. A goodly portion of The High And The Mighty’s substantial running-time is taken up by dramatic set-pieces, as each actor in turn is given his or her Oscar-Clip Moment, whether by speech or flashback or internal monologue or on-screen meltdown.

As it turned out, this proved literally true for Jan Sterling and Claire Trevor, who were each nominated for Best Supporting Actress, although they both lost to Eva Marie Saint. For Jan Sterling’s nomination, we can surely thank the same mindset that found Julia Roberts’ dressing down and putting on a push-up bra Oscar-worthy: in this film’s most bizarrely melodramatic moment, Sterling’s Sally McKee “disfigures” herself by smothering her face with cold-cream and wiping off her make-up. (Mind you, she reapplies it before the end of the film, because, you know, God forbid…) Claire Trevor’s nomination was more deserved, although she certainly gave better performances than this over the years. However, being the trouper she was, she really makes something out of her crudely-sketched character.

As it turned out, this proved literally true for Jan Sterling and Claire Trevor, who were each nominated for Best Supporting Actress, although they both lost to Eva Marie Saint. For Jan Sterling’s nomination, we can surely thank the same mindset that found Julia Roberts’ dressing down and putting on a push-up bra Oscar-worthy: in this film’s most bizarrely melodramatic moment, Sterling’s Sally McKee “disfigures” herself by smothering her face with cold-cream and wiping off her make-up. (Mind you, she reapplies it before the end of the film, because, you know, God forbid…) Claire Trevor’s nomination was more deserved, although she certainly gave better performances than this over the years. However, being the trouper she was, she really makes something out of her crudely-sketched character.

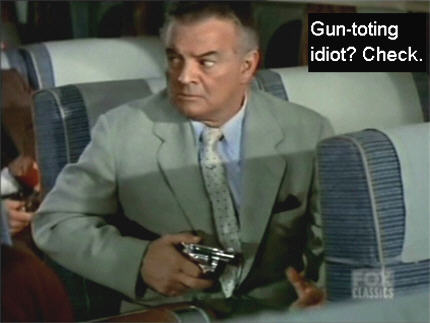

At the other end of the scale, while Ann Doran’s Clara Joseph, the film’s Helpless Whimpering Female, tends to attract the most viewer ire, it is Sidney Blackmer as the gun-wielding cuckold who gives the worst performance; Humphrey Agnew’s confrontation with Ken Childs, who Agnew believes to be his wife’s lover (incorrectly, as it turns out), is an absolute masterpiece of ham. I’ve seen a lot of praise for John Wayne’s contribution to this film, but in truth it is less that his performance is so good (although it is pretty good), than that it is a refreshing island of calm and restraint in a maelstrom of hysteria.

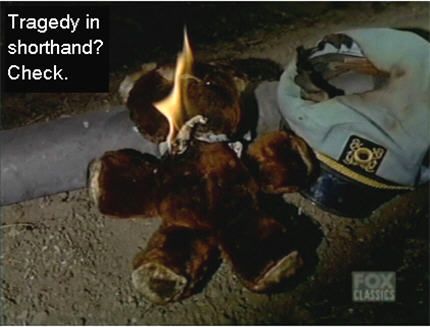

And speaking of an absence of subtlety, I defy anyone to sit through this film’s opening ten minutes without laughing, as The High And The Mighty buries the viewer under an avalanche of utterly shameless exposition. The opening scene is an encounter between Dan Roman and an old colleague, who then turns to his companions and blurts out the circumstances of Roman’s personal tragedy, the plane crash that killed all on board, including his wife and son, but left him with only scratches and a gimp leg.

We then cut to the ticketing desk of Trans-Orient-Pacific, where the passengers of Flight #420 are checking in. Now, I have to give the film the benefit of the doubt here, and assume that in the early fifties, when Hawaii was still a US territory, this really is the way things were; that people were obliged to walk up and identify themselves by stating their name, age and place of birth. In context, however, it plays like the most naked piece of shorthand, particularly in conjunction with the addendums offered by TOPAC’s ticket-agent who, by virtue of a previous job as “a night clerk in a Nevada hotel”, either knows all these people, or recognises “the type” well enough to fill us in.

Thus, Lydia Rice is summed up for us as having, “A grandfather who left her both brains and riches. She bought her husband an advertising agency not too long ago, because he wanted a new toy.” Meanwhile, Ken Childs is “one of the few men to make money from aviation”; theatrical producer Gustave Pardee – whose “New York shows” Mr Exposition enjoyed very much – has a trophy wife who “has done all right for a slender redhead from Ossowa, Michigan”; Sally McKee is “put together with paste and water”; while Humphrey Agnew, the owner-founder of a company making snake-oil cures, is dismissed as “a real quack”.

The oddest reaction, in a number of ways, is reserved for Dorothy Chen. When she has bowed herself away from the counter, Alsop breathes, “That face!”, while Miss Spalding adds, “The moon and the willow tree!” Now, I know that “The Moon And The Willow Tree” was sung by Dorothy Lamour in The Road To Singapore, but is there another significance to this that I’m missing? I’m rather hoping this wasn’t an all-purpose-Asian moment (China, Korea, Singapore, what’s the difference?). I’m also surprised that two people who live and work in Honolulu seem to find the sight of an Asian person so startling.

Truthfully, the film’s handling of both José Locota and Dorothy Chen is a bit on the nose. The two of them seem to be an advertisement for the “right” kind of immigrant: they are humble to the point of obsequiousness, and in turn are treated with a degree of condescension that sets the teeth on edge. Locota, with his naivety, his religious devotion, his exceedingly numerous family and his accent (suspiciously Scandinavian, for a supposed Latino, not to mention the stock Italian inflections) is right out of Hollywood’s Big Book Of Clichés; while Dorothy Chen is much addicted to speeches about how ugly and stupid she is.

It is noticeable that while most of the players get a big character scene, these two don’t. Now, call me crazy, but I’m thinking that given Miss Chen’s status as a Korean out of Manchuria, seeking refuge during the early fifties, her history would be far more worth hearing about than, say, the marital woes of Lydia and Howard Rice. Instead, Dorothy is reduced to starry-eyed amazement at her first exposure to Americans and American culture, rapturously repeating the expression dumb bunny over and over, once Miss Spalding introduces her to it.

Back at the ticket desk, we also meet unaccompanied minor Toby Field (played by William Wellman’s young son, Michael), and Ed Joseph, whose Ode To New Jersey – “That’s the Garden State! Motto: Liberty and Prosperity! Bounded to the north by New York, and to the south—” – marks him as this evening’s Odious Comic Relief. The experienced disaster movie viewer might initially be torn over the question of which of these two will end up torturing us the more.

Back at the ticket desk, we also meet unaccompanied minor Toby Field (played by William Wellman’s young son, Michael), and Ed Joseph, whose Ode To New Jersey – “That’s the Garden State! Motto: Liberty and Prosperity! Bounded to the north by New York, and to the south—” – marks him as this evening’s Odious Comic Relief. The experienced disaster movie viewer might initially be torn over the question of which of these two will end up torturing us the more.

After being introduced by his (onscreen) father, who speaks tremulously of the mother meeting him in San Francisco: “She’s brunette, and…very beautiful… ” – thus letting us in on the climax of his plot-thread – Toby does spend some time early on being, ahem, adorable; but then he crashes out on his seat and sleeps through the whole movie, as various adults tuck him in and ruffle his hair. In this, William Wellman was probably acknowledging his son’s limitations rather than taking pity on the audience, but it has the same effect. However, from Ed Joseph and his comedy stylings there is, alas, no escape for any of us; his “crying towel” speech has to be heard to be disbelieved.

The opening Avalanche Of Exposition concludes when we cut to our flight crew for Part 2 of The Dan Roman Story. Second Officer Hobie Wheeler, sucking on an ice cream cone, tries to figure out how old Roman must be, and in the process delivers the following casual speech:

“He was flying planes before I was born. Flew the air-mail in the open cockpit days; I think he learned to fly in the First World War. Then endurance flights, racing, old-time barnstorming… Ten or fifteen years with Trans-World. In the Second World War he flew a bomber in the Ploesti oil field raid; took his cracks at Germany in B-17s; finally ended up with a B-29 squad in Okinawa…”

I suppose we should be grateful that we don’t come away knowing what style of underwear Mr Roman favours.

Now, as our passengers and our flight crew board the plane, I’m impelled to stop and comment on something that is no reflection upon the film itself, but rather an unnerving relic of the time at which it was made: the total lack of airport security. These days, even the toy gun that Toby Fields has strapped to his hip causes an involuntary eyebrow lift; but the fact that Humphrey Agnew is able to carry a loaded handgun into the cabin without the slightest check or restraint is a real, Try telling the young people that moment. Astonishingly, it was another two decades before significant security protocols were introduced at airports, after world aviation was rocked by a wave of hijackings and bombings.

So Flight #420 takes off, and The High And The Mighty settles in for about two hours of – *shudder* – character scenes, mercifully broken up by the occasional seeming promise of a gruesome death for everyone concerned. Let’s look at some highlights, shall we?

Flashbacks:

– physicist Donald Flaherty, going Gauguin amongst the natives of a Pacific island while becoming a self-loathing drunk due to his secondment into a guided missile program (“I had a seat on a nice little campus…I played a pretty good game of golf…and I slept nights…”)

Speeches:

– Lydia Rice, sharing with us her vision of life in the wilds of Canada if her husband gets his way and swaps his advertising agency for a mine (“Go on off to your primeval forest! Play Daniel Boone! Make fire by friction! Eat out of cans! Take a bath Saturday night and go to an Eskimo hoe-down!”)

– Ed Joseph and his crying towel (“The booby-hatches are full of people who keep things to themselves…”)

Meltdowns:

– newlywed Nell Buck, sobbing over having to face up to Real Life (“I’m scared! I’m just plain scared!”)

– Sally McKee, scrubbing off her makeup (“Look at my face! Wouldn’t you walk away?”)

– pseudo-cuckold Humphrey Agnew, confronting Ken Childs (“I’m not such a fool as you and my wife seem to think! Now, I’m going to let you wonder what I’m going to do! – wonder, and think, and think, and think!”)

Granted, there are a few moments of psychological acuteness in the midst of all the Sturm und Drang: Gustave Pardee selflessly trying to comfort the hysterical Clara Joseph, as his wife of ten years stares in astonishment; the fact that it is, of all people, the uber-nice José Locota who finally, wearily, tells the incessantly moaning Humphrey Agnew to shut up; and arch-shrew Lydia Rice rising to the occasion, as long as there’s an occasion to rise to. (Lydia’s irritation with Clara Joseph’s snivelling helplessness is supposed to be a mark against her, I’m sure, but try a finding a viewer who doesn’t sympathise.)

As for the rest, it is tosh unadulterated, and all the more so for adhering to the dramatic convention that insists that people sitting next to you, or behind you, can’t hear you. Thus Gustave Pardee’s consoling of Clara Joseph, in which he assures her of his certainty of them landing safely, is followed by him sitting back down and announcing to his wife, well, of course they’re going to crash. Or Ed Joseph’s dissection of Howard Rice’s problems, through which the root of those problems, still sitting next to Howard, develops a convenient case of deafness.

Mind you, all this is just what happens in the cabin; you ought to see what’s going on up in the cockpit.

A further indication that The High And The Mighty is a disaster movie rather than a drama is the amount of time it spells dwelling on its characters, as opposed to the incident that drives the action, which is passed over with no detail as to what went wrong or how it happened. Early on, both Dan Roman and Miss Spalding observe a strange vibration within the cockpit; Spalding later notes two more such instances, each time when she is pouring drinks. John Sullivan is lying down when he becomes convinced that something is wrong with the plane, although no-one can identify its source.

It is just past the flight’s point of no return – of course – when there are two loud bangs, the plane lurches, and one of the engines catches fire. The fire is extinguished, at which point it can be seen that the propeller has been lost, damaging the wing – and the fuel tank – in the process, while the engine itself hangs askew, adding to the drag on the plane.

The loss of the propeller coincides exactly with Humphrey Agnew’s gun-waving meltdown, a fact that explains the most common misconception about this film: that it is the firing of the gun that precipitates the crisis. (Really, we can only blame William Wellman’s blocking of this scene for the confusion.) While I never thought this – the gun is pointing left-screen, the damaged engine is right-screen – I did think he fired it, which sent me scrambling for the specifications of the plane starring as Flight #420. In fact, upon closer examination, both bang-s emanate from the propeller; the gun isn’t fired at all; but that’s not going to stop me sharing with you the fact that the plane was a DC-4, and therefore not pressurised. This is why it is flying so low, and why Dan Roman can later safely open a door, so that baggage can be thrown out and the plane lightened thereby.

(As for the actual plane used, its history was more bizarre and tragic than anything that happens in this film: it began its professional life as the personal transport of Juan Perón; and ended it during a commercial flight with an engine on fire, and a crash into the ocean in which all lives were lost; a painful irony, considering the course of this film.)

The baggage-chucking follows on from calculations of distance, fuel, drag, height and wind-speed, which indicate that it is highly unlikely that plane will make its destination, but rather will have to ditch into the ocean. It also follows on from the revelation that the flight crew are just as given to speeches, flashbacks and meltdowns as the passengers.

One of the better staged scenes here comes when the fill-in-the-detail sequences for navigator Len Wilby and pilot John Sullivan are overlapped. Len “De-Nile-Ain’t-Just-A-River” Wilby’s verbal rhapsodies about his much-younger wife, in which he attributes her drinking and partying to her “spirit” and her sense of “little girl mischief”, fade in and out over Sullivan’s internal monologue, in which he concedes to himself his frayed nerves and “that chilly bundle in your belly”, as a cold sweat begins to form on his brow…

Another of The High And The Mighty’s casting travails occurred over the role of John Sullivan. John Wayne offered it to his friend Robert Cummings, who also happened to be a licensed pilot, which Wayne wanted. However, unbeknownst to Wayne, William Wellman had already offered the part to Robert Stack. The director got his way, which led to a few tense moments on the set, until Stack’s unconcealed admiration of his producer / co-star served to smooth Wayne’s ruffled feathers.

These days, many of us can only rejoice that Wellman prevailed. The High And The Mighty is, unmistakably, one of the inspirations for Flying High!, with Robert Stack playing the Ted Stryker role. It is impossible to believe otherwise than that Stack’s performance here was the reason for his subsequent casting as Rex Kramer, not least because many of the landing instructions barked at John Sullivan here are identical to those later barked at Robert Hays by Robert Stack. A number of this film’s character moments also have an equivalent in Flying High!, while the later film’s running joke of passengers who commit suicide rather than listen to one more minute of Ted Stryker’s endless flashbacks will win the heart of anyone who has sat through the middle portion of The High And The Mighty.

(The High And The Mighty also features scenes where TOPAC’s operations manager chomps through cigar after cigar while waiting to learn the plane’s fate, although sadly he never utters the line, “Looks like I picked the wrong week to quit smoking.” That piece of immortal dialogue emanated instead from Flying High!’s primary model, Zero Hour! And speaking of smoking, and of How Things Used To Be, just try counting how many times in this film someone lights a cigarette!)

So for most of the run home, the assumption is that Flight #420 will have to be ditched, and all preparations are made for that; but then Dan Roman begins to wonder whether maybe, just maybe, they couldn’t make it into San Francisco after all. This puts him at loggerheads with both Sullivan, whose nerves have begun to engulf him, and Wheeler, who considers Roman a dinosaur.

Of course, this is where cinematic convention is allowed to take over: it is John Wayne who thinks the plane should be landed, so obviously that’s right, regardless of the fact that the film has just spent about an hour explaining to us why that landing would be impossible. (Much more time is spent in the novel debating the pros and cons.) It also sets up this film’s most hilarious moment, as Sullivan and Roman begin squabbling in the cockpit over the right approach.

Encouraged by Wilby’s latest calculations, Roman tries to convince Sullivan to ease up on the power, in order to conserve fuel. When Sullivan freezes without saying yes or no to this, Roman goes ahead anyway. “Put those props back!” spits Sullivan “That’s an order!” It may be, but Roman disobeys it.

(But it’s John Wayne..!)

The plane lurches violently, threatening to stall. “It’s starting to shake!” cries Sullivan (although not to shimmy or to shudder). “Let it!” retorts Roman, arguing that they should do everything to at least try to give themselves a chance at a conventional landing. At last, though, Sullivan’s nerve fails altogether, and he announces his intention of ditching immediately into the ocean.

Roman’s solution? He reaches across and slaps Sullivan stupid.

Sullivan’s reaction? “Thanks, Dan. I needed that.”

Ah, physical violence! Is there nothing it can’t do?

The two men then exchange big cheesy grins, as Sullivan requests Roman to, “Whistle me a tune. I like music when I work.” And the plane is landed safely, with a minimum of fuss, as the landing lights of San Francisco Airport leap up into sight in the shape of a gigantic glowing cross, just to underscore the fact that the Good Lord is on John Wayne’s side. As if any of us doubted it.

Hysterical as that final sequence is, I find its attitude to the landing of the plane very strange indeed. The film spends scene after scene telling us just how narrow the margin is; and when the plane is inspected post-landing, it is found to have no more than thirty gallons of fuel left. In other words, it was about a minute away from dropping out of the sky and not only killing everyone on board, but wiping out a residential area of San Francisco in the process.

There are numerous real-life instances of the pilots of crippled planes making the decision to ditch specifically in order to avoid populated areas, and thus to minimise casualties; and yet Sullivan’s choice is presented to us explicitly as an act of cowardice. (As Roman slaps Sullivan, he also mutters disgustedly, “Get a hold of yourself, you yellow…”) I would very much like to show this sequence to Captain Chesley B. Sullenberger III of US Airways Flight #1549, and get his opinion on the subject.

The most amazing thing to me about The High And The Mighty is how, on the first attempt, it managed to set in stone the formula of the aviation disaster movie. Most prototype films merely introduce aspects that their descendants subsequently seize upon, but this one arrived complete and intact, and left its followers with very little room to move. (I have an unreasonable affection for Airport ’77 precisely because its creators put themselves to the trouble of coming up with something different.)

And of course, it makes no difference to the film’s designation as a “disaster movie” that in the end it contains no actual disaster – however much this outcome might aggrieve the neophyte viewer. There are two forms of aviation disaster movie, and both of them adhere rigidly to a single golden rule: you crash your plane within the first twenty minutes, or you don’t crash it at all. It isn’t only real planes that have a point of no return.

And you know something? For all that I’ve sat here alternately laughing and moaning at its histrionics and contrivances, I love this film. I love it for its histrionics and contrivances. I love it like I love all the classic [sic.] disaster movies. I just can’t help it.

Hey, some people love slasher movies; some people love films about Japanese girls in school uniform; some people watch the Lifetime Network. This is my secret shame.

Reviewing The High And The Mighty has made me put some thought into exactly what it is about this most maligned of genres that wins it such a place in my heart. If I define “classic” purely as “made between 1954 and 1984”, without any reference to the quality, or lack thereof, of the films in question, then I can say that a very big part of my affection for them does stem from the ensemble cast – and all the more so because of the fundamental lack of actual “stars”. Oh, you’ll find a few big names on board, sure; but so many disaster movies of this era feature predominantly a mix of fallen stars, with their best days behind them, and those invaluable, hard-working, second-tier people, finally being given a chance to shine (which may or may not translate to scenery-chewing).

Reviewing The High And The Mighty has made me put some thought into exactly what it is about this most maligned of genres that wins it such a place in my heart. If I define “classic” purely as “made between 1954 and 1984”, without any reference to the quality, or lack thereof, of the films in question, then I can say that a very big part of my affection for them does stem from the ensemble cast – and all the more so because of the fundamental lack of actual “stars”. Oh, you’ll find a few big names on board, sure; but so many disaster movies of this era feature predominantly a mix of fallen stars, with their best days behind them, and those invaluable, hard-working, second-tier people, finally being given a chance to shine (which may or may not translate to scenery-chewing).

This is an aspect that, I find, is becoming more and more important to me as I grow older, and gain more perspective, and a greater appreciation of the actors concerned. It’s like watching sixties and seventies TV: it isn’t about the shows themselves, necessarily; it’s about the people.

I see nothing to apologise for in taking pleasure in the contributions of actors like Myrna Loy and Henry Fonda and William Holden and Charlton Heston, even if they are slumming. I bow to no-one in my perverted affection for the Terrible Trio of George Kennedy, Ernest Borgnine and Slim Pickens. I’m not even ashamed of getting a giddy thrill out of Leslie Nielsen in full-on seventies dead-straight mode, or of making book on how they’re going to whack poor Shelley Winters this time.

On the other hand, when I find myself getting nostalgic over the likes of Jimmie Walker and Charo, I suppose it could be argued that I have a problem…

The other thing about disaster movies in general – and this certainly applies to The High And The Mighty – is that they are absolutely unironic. This is another quality that I find growing on me with the passing of time. I dunno, maybe I’m getting soft, or maybe just old; but these days I get more and more exasperated with the way that so many contemporary films insist upon letting the audience know that they’re in on the joke, even if there’s not really any joke there to start with.

There’s something refreshing, in contrast, in the completely straight-faced melodramatics of your average disaster movie. It may not be great drama – okay, it isn’t great drama – but by God, they mean it; and if we laugh, rather than thrill or sob, in the face of the personal travails of our various characters, it is, I hope, with real affection.

Besides, the fact is that, just every now and then, a disaster movie hits the mark quite sweetly. Such is the case with The High And The Mighty, which saves its moment of triumph for its very last scene, almost the only understated one in the entire film. It comes when all is over and the passengers have dispersed, when Dan Roman learns just how close they were to not making it safely down at all. He then turns and limps away, until the shadows engulf him and we hear only his whistle, the same signature tune that has recurred throughout the film. He is watched by the TOPAC operations manager, who says softly in his wake, “So long, Dan. So long, you ancient pelican.”

So much is encompassed in the use of this almost comical aviator’s phrase, here an endearment rather than an insult: Dan Roman’s age and his personal history, and the manager’s decision to hire him anyway, very obviously over strenuous opposition. I’ve read of people who saw this scene just once, during the film’s first release, and never forgot it. It worked in 1954, and it works today.

So I guess the laugh’s on me, huh?

For what it’s worth, that does look like a fairly standard setup for early approach lighting systems. Most of them have a lead-in stripe with a single crossbar for orientation. Here‘s a quick guide to the usual ones, but in the 1950s it was all pretty experimental so that might be actual stock footage.

LikeLike

Yes, it probably is—subsequent flight-film viewings would suggest so, though the overt cross arrangement seems to have given way to other designs fairly quickly.

Mind you—it’s still hilarious in context. 😀

LikeLike

It’s pretty cool to see you review one of the Duke’s pictures. Admittedly, not many of John Wayne’s movies fit the parameters of your site. 🙂 Have you evers seen “The Hellfighters”? The Duke leads a company that fights oil well fires. I love it, and it might fit in as disaster/technical. I am a huge fan of John Wayne, and it was really interesting to learn that he has a formative role in the Disaster Movie Genre. 🙂 Thank you.

LikeLike

Thank you. 🙂

Yeah, I’ve taken a look at Hellfighters in this context, but it didn’t pass the Disaster Movie Litmus Test. So it’s unlikely we’ll be seeing another full-on John Wayne review here—but he has already popped up in Et al., and doubtless will again.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ve thought at times of writing reviews of Westerns and war movies, perhaps I’ll try one of my favorite Duke movies and see if I enjoy the process, and start a movieblog of my own. 🙂

LikeLike

You should! 🙂

LikeLike

Speaking of John Wayne films, while The Searchers isn’t a horror movie in the conventional sense, it does have what I consider to be one of the most terrifying sequences ever filmed. The buildup to the Indian attack on the homestead scared the crap out of me as a kid, and even 30-odd years later it still gives me the creeps. Many modern horror directors could learn a lot from that sequence. Not to mention the results of the Indian attack, which, through the power of suggestion, manage to be far more horrifying than many a gore-fest; a classic example of how the viewer’s imagination can conjure far more terrible things than would be possible to show.

Of course, it’s a great movie in many other ways, but purely from the perspective of a horror movie buff, it has a lot to offer.

LikeLike

Agreed, though even with a lot of squeezing it doesn’t really fit within my site parameters. (Might show up in Et Al. some time, though.)

LikeLike

I admit to ignorance regarding international title changes. “Flying High!” I take it from context, is the movie released, here in its country of origin, as “Airplane!” It would appear some research is in order, on my part.

LikeLike

Yes, that’s right: presumably the non-local spelling of the original title was the issue, plus the change let them slip in a drug reference… 🙂

LikeLike

Thank you. I’m coming here regularly now and enjoying it greatly. Up to J in the complete index.

LikeLike

Unrelated to this post semi sort of but wanted to send a comment/message regardless… Found out about a Disaster AND Killer Shark film combined called Cyclone from 1978.

Plot: An airplane goes down in the ocean during a storm and a few survivors find refuge on a small tour boat. Swept out to sea, these people slowly starve to death in the hot sun with barely any food or clean water. With no place to turn, the boat survivors resort to cannibalism to stay alive…that is ..until the rescue planes come to pick them up and the man eating sharks decide it’s time to eat as well.

Directed by Rene Cardona Jr, apparently features his de rigeur actual shark stuff (supposed real corpses were used for some of the eating scenes) and also a host of washed up actors doing the disaster thing.

Moving to the top of my watch list, figured you’d want to know, had you not heard of or seen it before.

LikeLike

General chatter, please! 😀

Own it, haven’t watched it. My relationship with RC Jr is…contentious. Actually, “abusive” is probably a better term….

LikeLike

John Wayne was in fact 11 when World War One ended; it’s interesting to me that he was actually playing someone OLDER than his real age (compare to the modern botoxed actors who frequently play quite a bit YOUNGER). Spencer Tracy was born in 1900, so he would have been marginally more believable in the role. I guess either looked plenty old enough though, thanks to boozes and cigarettes!

LikeLike

Speaking of AIRPLANE! / FLYING HIGH!, “Humphrey Agnew” (two American vice-presidents) sounds like a name right out of a parody.

LikeLike