“I am…Dracula. I bid you…welcome.”

Director: Tod Browning

Starring: Bela Lugosi, Edward Van Sloan, Helen Chandler, Dwight Frye, David Manners, Frances Dade, Herbert Bunston

Screenplay: Garrett Fort, based upon the novel by Bram Stoker, and the play by Hamilton Deane and John L. Balderston

Synopsis: As a carriage travels rapidly through the Transylvanian mountains, English businessman Renfield (Dwight Frye) asks the driver to slow down. A local traveller immediately intervenes, warning the bewildered Renfield that it is Walpurgis Night. At an inn, where the other travellers disembark, Renfield announces that he is going on to the Borgo Pass, where a carriage from Castle Dracula will meet him. When the horrified villagers are unable to dissuade him, the innkeeper’s wife presses upon Renfield a crucifix. As the sun sets, the inhabitants of Castle Dracula rise from their coffins: Count Dracula (Bela Lugosi) himself, and his three undead wives… At midnight, Renfield boards the carriage waiting at the Borgo Pass, which heads off at a dangerous speed. Leaning out of the window to remonstrate, Renfield is astonished to see an enormous bat flying just over the horses’ heads. When the carriage arrives at the castle, Renfield hurries forward to speak to the driver – only to discover that there is no driver… The castle doors swing open, and Renfield enters with great trepidation, finding himself in a crumbling ruin. A tall man in evening clothes moves slowly down the castle staircase, and introduces himself as Count Dracula. A little reassured, Renfield follows his host upstairs – staring in shock, as Dracula seems to pass through a huge spider’s web without touching it. Upstairs, Renfield finds himself in more cheerful surroundings, with a fire, a meal and his luggage waiting for him. Dracula looks over the papers of Carfax Abbey, the old house in England that he has leased. Distracted by his host’s behaviour, Renfield cuts himself. Dracula approaches rapidly, seemingly mesmerised by the blood – then recoils as Renfield’s crucifix falls forward over the wound. Dracula pours wine for Renfield, declining to partake himself, and then withdraws. Before long, Renfield is overcome by dizziness. He staggers to the glass outer doors and throws them open. A bat swoops outside them. Renfield collapses. The three vampiric women glide into the room, but are driven back by a gesture from Dracula, who has materialised by the doors. He leans over the prostrate Renfield… When a schooner, the Vesta, sails into Whitby Harbour in England, its entire crew is found dead, the captain lashed to the wheel. The only living passenger is a giggling, raving Renfield… As Dr Seward (Herbert Bunston), his daughter, Mina (Helen Chandler), her fiancé, John Harker (David Manners), and her friend, Lucy Weston (Frances Dade), enjoy a concert in London, a man introduces himself as Count Dracula, their new neighbour. He explains that he has leased Carfax Abbey, which lies adjacent to Dr Seward’s Sanitarium, in which Renfield is now confined. Later that night, Lucy confesses to Mina that she finds Dracula fascinating. The girls retire to their rooms. Lucy opens her windows before going to bed. An enormous bat appears outside them. The next moment, Dracula has materialised. He approaches the helpless Lucy, leaning towards her unprotected throat…

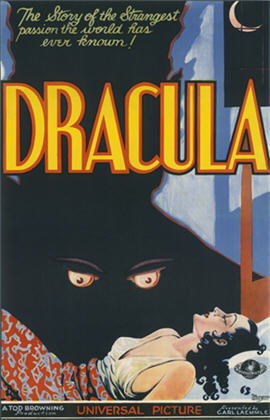

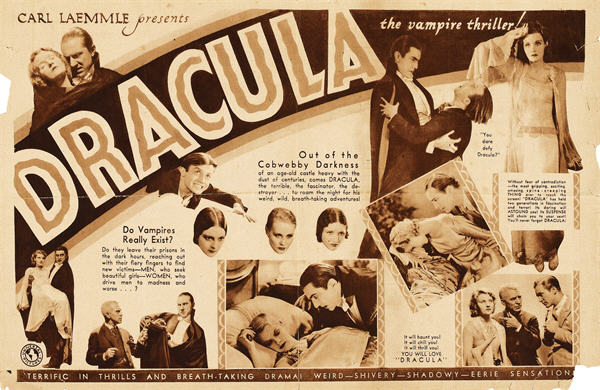

Comments: Motion picture history was made upon the 12th of February, 1931, when Universal Studios opened its screen version of Dracula in New York City. In stark contrast to the many frankly uncanny films that had emanated from Europe, particularly from Germany, during the 1920s, the American cinema had tended previously to shy away from the genuinely horrific, preferring to dismiss mysterious events with a final scene “explanation” that generally involved dreams, scheming lawyers and/or escaped lunatics.

But with Dracula, viewers were for the first time in an American production confronted by the unmistakably supernatural. Before the film was two minutes old, audiences heard the word “Nosferatu”; before six minutes had passed, they had witnessed Count Dracula and his undead brides rising from their coffins.

The road to this cinematic milestone had been long and tortuous. Screen versions of Dracula had been touted since the early twenties. Lon Chaney was eager to play the title role, and plans were made for an early talkie to star Chaney, with direction by his long-time collaborator, Tod Browning. The two had previously dealt with vampiric themes when working on one of the most famous of all lost films: London After Midnight, a textbook example of “explained-away” horror.

Sadly, however, the screen’s leading horror icon succumbed to cancer in 1930. Equally tragically – in my opinion, at least, although no doubt I’m in a minority – the version of Dracula proposed by producer Paul Kohner, intended to star Conrad Veidt under the direction of Paul Leni, had already been abandoned following the shockingly premature death of Leni in 1929.

(In time, Kohner would indeed find himself producing a screen version of Dracula…but that’s another story, as we shall see.)

Added to these calamities, Universal Studios president, Carl Laemmle Sr, had been unenthusiastic about the project from the outset, finding the subject matter morbid and distasteful. He was not alone in this opinion: the story was widely considered to be so revolting as to be “unfilmable”.

However, Laemmle finally succumbed to the combination of pressure from his son, Carl Jr, and the fear that, if Universal passed on the opportunity, a rival studio would cash in: for reasons that Carl Sr was unable to comprehend, the stage version of the story had been an enormous success.

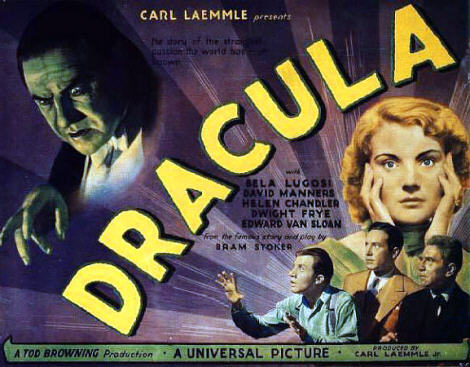

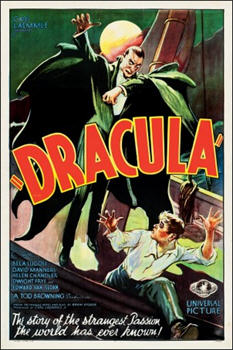

And so Dracula went into production, directed as planned by Tod Browning, but now starring a little known Hungarian actor, Bela Lugosi, who had played the leading role of Count Dracula on stage, and who, after considering and rejecting a whole series of other actors, Universal grudgingly signed up for a measly $500 a week. When Dracula was finally released, Carl Sr was nervous, concerned that the film had gone too far in its depiction of the macabre. (The studio’s uncertainty about what the public’s response to Dracula would be is clear in the film’s amusingly oblique tagline: “The story of the strangest passion the world has ever known!”)

As it turned out, Laemmle need not have worried. The critics were unimpressed by Dracula, the morals campaigners were up in arms against it – but the paying public ate it up. Bela Lugosi was an overnight sensation, and in 1931, Universal Studios – soon to be known as “The House Of Horror” – made a profit for the only time during the era of the Depression.

Viewed today, it is difficult to believe that anyone could ever have considered that Dracula went “too far”. On the contrary, the film is most remarkable for its stubborn refusal to be at all cinematic, still less horrific.

To a large extent, this unfortunate state of affairs can be blamed upon the film’s rocky production history, including the studio’s decision to get around the expensive issue of rights by basing Dracula not upon Bram Stoker’s novel as such, but upon the stage version of the story which had been so successful in both Britain and America. The play, written by British producer-actor Hamilton Deane, and extensively re-written by American playwright John L. Balderston, who considered Deane’s version atrocious, made many drastic alterations to the story.

(There is an almost knee-jerk tendency these days to badmouth Stoker’s novel. In my opinion, while Dracula can by no stretch of the imagination be considered great literature, it’s still a darn good read; and compared to the play, it’s a masterpiece.)

The Transylvanian scenes were eliminated altogether, and Dracula himself, an unseen evil force for most of the novel, was brought front and centre, being transformed from Stoker’s loathsome and shadowy creation into a smooth-talking Lothario quite at home in the drawing-rooms of the modern world. Still, when the play was staged, it kept at least some of the story’s shock moments; and it dared to throw a little sex into the mixture, too, by having Dracula preface his neck-biting activities with passionate kisses.

The film, alas, is lacking even these moderate virtues – although thankfully, it did restore the novel’s Transylvanian opening. These scenes are without question the highlight of Dracula; atmospheric and imaginative, they are so far removed in both attitude and execution from the static and talky sequences that make up the latter two-thirds of the film that it is difficult to believe that the same people were responsible for them; and indeed, a fair degree of controversy has arisen over the years as to this very point.

It seems certain that Universal, unhappy with Tod Browning’s work, removed as much as ten minutes from his original cut. This may account for the abrupt and jerky nature of the latter part of the film, and the way in which certain story elements – the ultimate fate of poor Lucy Weston, for instance – are simply left unresolved.

However, the waters of Dracula were further muddied some years ago when David Manners, by then the only survivor of the film’s cast and crew, claimed that most of the London scenes had in fact been directed, not by Tod Browning, but by cinematographer Karl Freund – and, since Freund’s English was limited, that he did it through an interpreter.

While the whole truth of the matter will probably never be known, these behind-the-camera skirmishes can have done nothing to help a production already struggling under the combined weight of budgetary restrictions, the technical limitations of the era, the difficult transition from silent to sound cinema, and worries over censorship. Together, these factors helped to make Dracula a frustrating and unsatisfying experience, with all of the story’s dramatic highlights – the Vesta’s nightmarish voyage to England, Mina’s vampiric “baptism”, Dracula’s rat-plague temptation of Renfield, Lucy’s undead activities – kept strictly offscreen, and described to the audience after the event.

The final insult is the climactic staking of Dracula, which is not only unseen, but was for many years aurally censored, with the vampire’s dying groans removed from the soundtrack. And while the recent restoration of these sounds is very welcome, the fact is that their presence does little to improve one of the limpest and most anti-climactic endings to a film imaginable.

But despite what I have said so far, in truth I am here not to bury Dracula, but to praise it. The film is a landmark of incalculable importance, and should – must – be judged in its own historical context. It ought always to be kept in mind, for example, that at the time of its release Dracula, along with its soon-to-be-produced companion-piece, Frankenstein, was considered to be the ne plus ultra of horror. Audiences were terrified by these films, and shocked by their content.

In fact, the widespread disapproval of the grimness of Dracula’s storyline would ultimately have a very unfortunate long-term consequence: it subsequently became standard procedure for American horror movies to include amongst their characters – yes, a comic relief. Coming first, Dracula is, mercifully, less afflicted by this painful convention than are most of the films that followed it, and is all the better for it – although we still have to suffer through the far too frequent appearances of Martin, the asylum orderly, and his endlessly reiterated cries of, “He’s crahhhzy!”

In this atmosphere of condemnation, for the supernatural aspects of Dracula to be handled so forthrightly was a daring step forward; and even now, so many decades later, the slow glide of Karl Freund’s camera into the crypt of Dracula’s castle, the lifting of those coffin lids, and the silent, synchronised movements of the three Weird Sisters are quite capable of inducing in the viewer a distinctly pleasurable shiver.

The opening scenes of Dracula have attained their own kind of immortality: the unwary traveller who fails to heed the warnings of the terrified peasantry would become one of the horror film’s most enduring clichés. The inside of Castle Dracula, cavernous and cobwebby, is a beautiful piece of set design, and a deliciously off-kilter atmosphere is created by some very odd casting choices from amongst the animal kingdom: the bee that crawls out of a miniaturised casket, for one, and the opossums hired as stand-ins for the censor-disapproved rats, for another.

And heaven forbid we should overlook one of Dracula’s strangest moments, the wholly unexpected appearance of one of the world’s rarest animals: the Lesser Scuttling Transylvanian Armadillo. Less welcome, however, and certainly one of the film’s more embarrassing aspects, is the bat into which Dracula transforms himself at regular intervals: if only someone had managed to convince the film-makers that bats don’t bounce! (Nor do they generally come with strings attached: oh, that DVD clarity – !)

So accustomed are we to thinking of Dwight Frye’s Renfield in terms of the giggling lunatic he becomes in the wake of his encounter with Dracula, upon rewatching this film the early scenes featuring “normal” Renfield tend to come as a bit of a shock—but they underscore his role as hapless victim, “the unwary fly”. Having chosen to ignore the warnings of the locals, the unfortunate Renfield finds himself in the wilds of Transylvania, confronting a host who not only makes affectionate speeches about wolves and spiders, but who can pass through spiders’ webs without touching them…

Trying desperately to appear as if he has noticed nothing out fthe ordinary, Renfield unwisely tastes the very old wine that he is offered, and soon afterwards collapses by the French windows of his room, as a bat flaps outside them and the three vampiric women glide toward him. His crucifix strangely ineffectual, Renfield then makes motion picture history by becoming Dracula’s first ever official cinematic victim.

(Eager as he was about the film in general, the overtones of this scene bothered producer Carl Laemmle Jr, who thought that Dracula’s victims should only be female...)

Alas, from this point in the film it is downhill all the way – dramatically speaking, at least. The voyage of the Vesta, one of the highlights of Stoker’s novel (and in fairness, intended to be a highlight here, too, before the budget was slashed), is reduced to little more than a few pieces of stock footage lifted from the silent film, The Storm Breaker. Then the story shifts to London, and to Dr Seward’s Sanitarium (which mysteriously manages to be “near London” and “near Whitby”, which is in Yorkshire, all at the same time), and Dracula becomes as stage-bound as any play could ever be.

Short on dramatic flourishes that might distract the audience, it becomes apparent just how poor the film’s script, at least as filmed, really is. Most striking, perhaps, is the complete absence of any motivation. Just why does Dracula go to England? Why does he batten onto the Sewards? – and why does he feel compelled to wander in and out of their house, when all he ultimately achieves by doing so is to give himself away to Van Helsing? And why, for that matter, with Dracula being the social smoothy that we see here, is Renfield’s presence in the Sanitarium necessary at all? All of these issues are blithely disregarded.

And while at this late date I can’t help but notice these obvious shortcomings in the story, perhaps, in order to do Dracula justice, I should disregard them, too, and focus my attention where audiences of 1931 – and beyond – certainly had theirs focused: upon the weird, compelling, unique performance at the centre of the film: Bela Lugosi as Count Dracula.

Ah, Lugosi… What can one say – what is left to say – about his interpretation of Dracula? After nearly one hundred years of imitation and parody, reference and ridicule, it is impossible to view Lugosi’s performance in any kind of objective light. It exists beyond criticism. It simply – is. What we have here is one of those rare, freakish marriages of actor and material that makes each inseparable from the other.

This version of Dracula with anyone else in the leading role is now unimaginable; and unfortunately for Lugosi, it quickly became evident that people had equal difficulty accepting him doing anything but Dracula. Hampered by the limitations of his acting range and his stubborn refusal to conquer the English language, Lugosi soon found himself typecast beyond any possibility of recovery. Dracula would prove to be both the alpha and omega of his career. Perhaps, then, it is only fitting that the role should have achieved an immortality of its own. Everyone knows Lugosi’s Dracula – even people who have never bothered to see the film.

If the screenplay of Dracula is, on the whole, quite poor, it at least served up whole chunks of juicy dialogue for Lugosi to get his fangs into. While it goes without saying that Lugosi’s interpretation of Dracula is light years from Stoker’s conception of the character (then again, in that regard why single out Lugosi?), there are aspects of it that are just – right; like his strange, jerky, mis-emphasised (and possible phonetic) delivery of his lines, which inadvertently gives the impression not just that Dracula isn’t used to speaking English, but that he isn’t used to speaking at all.

Dracula is endlessly quotable. Who could ever forget the Count’s introduction of himself to the terrified Renfield? His frank enjoyment of the howling of the wolves (“Listen to them! Children of the night! What music they make!”)? Or his insistence that he never drinks – wine; his plans for leaving Transylvania, an event that will occur “tomorrow eeeve-ning”; or his parting shot at his mortal enemy: “For one who has not lived even a single lifetime, you are a wise man, Van Helsing!”

(One of Lugosi’s other memorable quotes – “To die – to be really dead – that must be glorious!” – is completely out of character for this Dracula, who has not a hint about him of the “tragic romantic”, which would later become the dominant interpretation of the vampire.)

Looked at squarely, however, it is easy enough to see the flaws in this characterisation of Dracula. Indelible though his performance is, I’m not entirely sure that you could call what Lugosi does great acting. Moreover, the film’s attempts to convey “the ultimate evil” are fairly dismal. Those broad gestures and facial contortions (probably transferred over from Lugosi’s stage performances, and insufficiently toned-down for the cameras), that spotlight across his eyes meant to convey his hypnotic powers (which might have been more effective, had it ever managed to hit the mark!), and – oh, dear! – that lipstick, are all risible rather than otherwise.

Of course, none of these things were actually Lugosi’s fault. Perhaps the situation is best summed up by saying that what is wrong with Lugosi’s Count was the responsibility of the film’s producers; what is right is – all Lugosi.

But Lugosi’s is not the only enjoyable performance in Dracula. He is well-matched by Edward Van Sloan, who also transferred his interpretation of Professor Van Helsing from the stage to the screen. Among its many other legacies to the genre, Dracula initiated the classic “monster vs savant” scenario that would recur across the decades in horror films without number; and Van Helsing himself is that beloved genre figure, the “Professor” (discipline unidentified) who has devoted his life to the study of, “Little known facts, which the world is perhaps better off not knowing.”

The introduction of Van Helsing in Dracula is my favourite scene in the whole film. Well—what else would that be, but the moment when Van Helsing pours something from a measuring cylinder into a test tube, then announces as a consequence, “Gentlemen, we are dealing with the undead!” (Ah, science!)

Much of the acting in Dracula is extremely creaky, suffering from all of the faults of early sound productions, but the battles of will between Dracula and Van Helsing can be enjoyed without reservation, with both Lugosi and Van Sloan rising admirably to the occasion. By the end of it, Edward Van Sloan has had almost as many quotable lines as Lugosi, including his landmark utterance, “The strength of the vampire is that people will not believe.” How many variations of that line have there been over the years? I also adore the moment when Van Helsing inquires of Mina, oh-so-casually, “When was the last time that you saw Miss Lucy, after she was buried?”

Dracula’s other most praiseworthy aspect is the performance of Dwight Frye as Renfield. While it is unlikely that modern audiences will find all that much to bother them in this film overall, there is one thing about it that is disturbing by any standard, and that is Renfield’s literally unearthly laugh, first heard as he crouches within the hold of the mysteriously deserted Vesta, his eyes wide and his teeth bared at the approaching officials – and the audience.

Renfield’s ability to come and go as he pleases within the Sanitarium is ridiculous, granted, but Dwight Frye nevertheless contributes some unforgettable moments, including his frequent hysterics within his cell, his mocking summation of Van Helsing’s dissertation upon vampires (“Isn’t this a strange conversation, for people who aren’t crazy?”), and his vivid description of the moment when Dracula came to him with an irresistible offer: a temptation couched in strangely Biblical terms (“All this will I give to you…”).

The tragedy of Dracula is that its three central performances were so effective, the men who gave them could never afterwards quite manage to escape from the vampire’s undead grasp. Lugosi and Frye spent the remainder of their respective careers trapped in genre that had made them stars. Van Sloan did a little better, although the majority of his non-genre roles were small, and rather negligible.

The rest of Dracula’s cast is very ill-served by the screenplay. Helen Chandler is far too brittle and shrill as Mina, at least during the early stages of the film. She is better once she has fallen victim to Dracula, particularly during her “knowing” conversations with Van Helsing; and she does score one indelible moment of her own: as night falls, Mina suddenly finds herself less interested in John Harker’s rhapsodies about the moon and stars, than she is in his temptingly exposed throat…

Not surprisingly, almost all of the original story’s sexual implications are missing from this version of Dracula. However, when Mina insists to John that, “You must not touch me, must not kiss me”, Chandler manages briefly to restore a hint of the novel’s subtext.

As for David Manners— Well, as the saying goes, if you looked up “thankless” in the dictionary, you’d find a picture of David Manners playing John Harker. Manners hated his role in Dracula. In fact, he hated everything about the production, and you can’t blame him a bit. Harker is thickheaded, ineffectual, and boring. Sadly for Manners, like Lugosi, Van Sloan and Frye, he too soon found himself typecast in these pointless “romantic lead” roles, and in response quit acting altogether. As Dr Seward, Herbert Bunston is just as useless and uninteresting as Harker; while the screenplay’s dismissal of Frances Dade’s Lucy – whose death in the novel is dragged out for chapter after agonising chapter, and whose staking is one of the gruesome highlights of the story – is nothing less than cruel.

On the other hand, the opening scenes of Dracula display some effective glass matte work, as Renfield travels through the mountains of Hungary, and the design of Dracula’s castle is imaginative and rather grand. The film’s photography indicates conflict between Tod Browning and Karl Freund, with the director’s preferred static style broken up every now and then by a sudden gliding movement more typical of the cinematographer’s body of work, as in the opening shot of Dracula’s crypt, or the introduction of the Seward Sanitarium.

As was typical at the time, Dracula has no score; its silences are only occasionally broken by ambient music – the concert which the protagonists attend, the music box in Lucy’s bedroom; and of course, the use of “Swan Lake” over the opening credits, which soon became a Universal horror movie trademark. However, it is now apparent that Dracula was not quite so “silent” as decades of mis-used, mis-stored prints may have led us all to believe. Restoration of the film has brought back to life Tod Browning’s experimental use of sound effects, which until recently were buried beneath accumulated layers of hissing and crackles. Unfortunately, as with most of Dracula’s other virtues, these effects are largely confined to the first third of the film; and on the whole, the production is very typical of the silent-to-sound transition era, displaying all too obviously the technical and artistic hesitations and limitations of the time.

To the delight of the bewildered Carl Laemmle Sr, Dracula became Universal’s highest earning film of 1931, and helped pulled the studio back from the brink of a yawning financial abyss. Moreover, Dracula was one of the top-grossing films of 1931 right across the board. Vindicated, but nevertheless worried that his production’s success might prove to be a flash in the pan, Carl Jr immediately pushed Frankenstein into production. The other studios, equally surprised by this peculiar taste for horrors suddenly evinced by the public, rushed to follow suit with fright films of their own. The rest is history.

Primitive as the production may appear today, the importance Dracula in the development of screen horror cannot be overestimated. This film not only brought the horror film forward into the sound era, but it crossed a critical Rubicon when it refused simply to explain away its monster. It took a stake through the heart to dispose of Dracula; a smug Professor waving his pipe around while he assured his astonished audience that, “The whole thing was really very simple!” was no longer enough.

As is the case with many “classic” films, Dracula requires the modern viewer to approach it with a sense of good will; with a willingness to enjoy, and to understand. It is easy enough to see what is wrong with the film; it perhaps takes a little more work to discover what is praiseworthy. Some viewers may find it difficult to get past Lugosi’s theatrics, the slow and stately unfolding of the story, and the concept of a vampire who is not permitted to bare his fangs; but in the end, if the effort is made, the rewards are there to be found.

Of course, there will always be those who can look at Dracula and see nothing but fodder for ridicule. While this is sad, the loss is certainly theirs. The horror film is nothing less than a record of the often-unarticulated fears and apprehensions of mankind, and the way in which they have shifted over the years. To see and to understand the evolution of this much-maligned – unjustly maligned – genre is a fascinating experience. Although there are some who will never understand the attraction of the horror film, there are many of us who share “the strangest passion the world has ever known”; and who understand that to love the genre without embracing its history, its roots, is not truly to love it at all.

Want a second opinion of Dracula? Visit 1000 Misspent Hours – And Counting.

*****************************************

But wait! There’s more!

******************************************

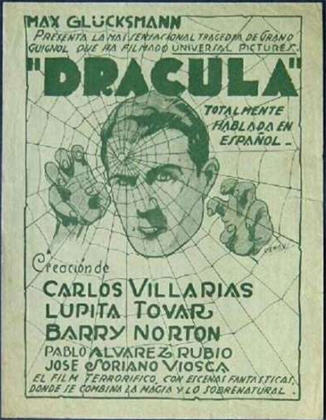

Dracula (1931) (Spanish language version)

.

“Today is Walpurgis Nacht, the night of bad omen. Nosferatu – ! The dead come out from their tombs and suck the blood of the living…”

.

Director: George Melford

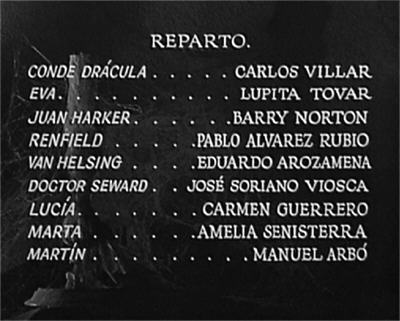

Starring: Carlos Villarias, Lupita Tovar, Eduardo Arozamena, Pablo Álvarez Rubio, Barry Norton, José Soriano Viosca, Carmen Guerrero

Screenplay: Baltasar Fernández Cué and Garrett Fort, based upon the novel by Bram Stoker, and the play by Hamilton Deane and John L. Balderston

.

.

Comments: The Universal “Classic Monster Collection” DVD of Dracula is something to be treasured forever, not least because it includes a print of one of the most talked about, and least seen, of all horror movies: the Spanish language version of Dracula that was shot simultaneously with the English language version. This production utilised the same sets and the same script, but had an entirely different cast and crew who worked through the night after Browning & Co. had wrapped for the day. The inability of the public to see this almost legendary film had the effect, inevitably, of increasing its mystique; and over time, a heresy began to be whispered – namely, that the Spanish version was better than its famous American counterpart. Now, thanks to Universal, we can see and judge for ourselves.

The Spanish version follows its rival quite closely with regards to the script, although with the inclusion of longer scenes and more subplots; so I won’t bother to recount the story again. Here, Mina is called “Eva”, John Harker is “Juan”, and Lucy Weston is “Lucia”. The other character names are unchanged.

The first thing that we discover is that awarding the title “better” to either version is not a simple matter. Both of the films have their particular strengths and weaknesses. One thing that must be conceded is that the Spanish version is far more technically accomplished, thanks to the direction of George Melford and the cinematography of George Robinson. Scenes are more interestingly constructed, with tension built through skilful intercutting; while the camera-work is assured and fluid, and offers imaginative visuals such as the shot of the drugged Renfield seen through the French windows he is struggling to open, with the three “brides” standing behind him on the far side of the room.

Better use is made overall of the film’s production design, with the camera roaming constantly so as to get as much out of the various sets as possible. The optical effects, although nothing extraordinary, are confidently deployed: there is no cutting away when Dracula rises from his coffin, for instance, but a simple though effective manifestation from a cloud of smoke. This film also has the unfair advantage of unfamiliarity: each new camera movement and placement strikes the viewer as fresh and original. Altogether, the film looks much more modern than Browning’s hesitant effort.

The Spanish version also benefits from not being so hampered by censorship worries. Vampirism is much more frankly dealt with: for example, the American version uses the word “Nosferatu”, but the Spanish version explains what that means. We are allowed to see the fang marks on the throats of the victims and, most startling of all – particularly for those of us scene-by-scene familiar with the American version – when night falls and the vampire’s power gains its ascendancy, Eva actually bites Juan on the throat, snarling like an animal when she is driven back. Eva is also permitted to be far sexier than Mina: she spends much of her time in low-cut dresses and thin, clinging nightgowns.

Carlos Villarias, this version’s Dracula, also manages to get a lot of mileage out of his cape, enveloping his victims in a manner both threatening and sexual. Dracula’s brides, who intriguingly are visually modelled upon their description in the novel – and who bear little resemblance to the women in the crypt whom we first see! – are not mere wraiths, but active, and hungry for blood.

(Which they get. Perhaps Carl Laemmle Jr wasn’t the only one concerned about the implications of Dracula biting a man: we do not see him attacking Renfield in this version.)

And again, the vampire women are clad in gauzy négligées rather than in shrouds. On the other hand, Dracula’s staking takes place off-camera in this version, too, so perhaps that was simply beyond the pale for the time. And finally – here a rat is a rat, and an opossum an opossum! On the downside, there are no armadillos in this version. (Nurks.)

It is fascinating to note the points at which the two versions intersect. Many scenes appear in both films, including all of the location (or pseudo-location) footage, such as the carriage approaching the inn. Costs were also saved by making up Carlos Villarias to look as much like Lugosi as possible, thus allowing long shots of Lugosi himself to be used in this film.

Conversely, the Spanish version includes footage that didn’t quite make it into the American version – shots that occur just before or after the footage that did, or were rejected for some other reason. Thus, one of the Weird Sisters glides out of shot, just as we begin to watch her; the mysterious bee, which climbs out of its casket in the American version, walks around that casket here; and, most amusingly, an unfortunate opossum tumbles off a coffin and onto the floor, crying out indignantly the while. We assume that this was an American outtake.

The American version of Dracula, thanks to ruthless cutting by Universal, is a mere 75 minutes long. The Spanish version is almost half an hour longer, which is both a good thing and a bad thing. Plot threads and character fates simply left hanging in the American version are finally resolved here; poor Lucy – Lucia, I mean – is granted the only kind of closure possible. Also, we finally learn what Renfield does to the maid after she has fainted, a scene made unsettling in the American version by an inconclusive fade to black. (I won’t tell you what he does, but it is unexpected – and frankly, a bit of a let down.)

There are also some differences in emphasis between the two versions that are extremely interesting. For example, and not surprisingly, many of the twisted Biblical references that are scattered throughout the American version, from Dracula’s observation that, “The blood is the life!” onwards, are absent from the Spanish version; while the image summoned up by Van Helsing of the ultimate fate of Renfield’s soul, should he refuse to assist the vampire-hunters, is much more specific and intense.

However, if the American version of Dracula is annoyingly truncated and abrupt, it must be conceded that the Spanish version is way too leisurely, lingering over scenes for far longer than is necessary. That in which Van Helsing tries to convince Renfield to co-operate with him, for instance, seems to go on forever.

And then we have the two casts. Those people who consider Lugosi’s Dracula to be overdone and hammy have obviously never seen Carlos Villarias’ interpretation of the character. The Spanish Dracula goes through much of the film with his eyes as wide open as possible and his lips pulled right back, sometimes in a snarl, but more often in a singularly dopey grin. This smile may have been intended to be menacing, but as a result of it Villarias comes across like a second-rate Vaudevillian about to launch into a song and dance routine, or tell a string of dirty jokes. Moreover, the nose wrinkle and facial contortion that Villarias produces upon seeing a crucifix tends to suggest, not ultimate Evil recoiling from ultimate Good, but instead that Dracula smells something nasty. (Perhaps he does…)

In fairness, as the film progresses Villarias does rein in his face-pulling, and is much more effective as a consequence; but by then the damage has been done. Ultimately, Carlos Villarias’ performance has the rare distinction of making a Bela Lugosi performance seem restrained by comparison. Even his death groans outdo Lugosi’s!

The two Renfields are an intriguing pair. While Pablo Alvarez Rubio’s constant hysterical screaming cannot compare with Dwight Frye’s hideous laughter, Alvarez is given more chances to really act than his counterpart, and has some very interesting scenes – particularly his “fly-catching” episode in Seward’s study. Eduardo Arozamena, on the other hand, lacks the authority of Edward Van Sloan, although it is enjoyable to see his character being summoned from Europe to England for his expert assistance, as happens in the novel. Lupita Tovar is luminous as Eva, and has the advantages over Helen Chandler discussed above. While the greater experience of the stage-trained American actress is evident, Tovar is much more natural and energetic than Chandler, who is very stiff as Mina.

(For Tovar, of course, making Dracula had important personal repercussions. Paul Kohner, who had been so eager during the 1920s to make a version of Dracula, ended up producing this Spanish one – and marrying its leading lady. The couple’s daughter, Susan, would be nominated for an Academy Award in 1960 for her performance in Imitation Of Life.)

Barry Norton’s Juan is not quite so much of a drip as David Manners’ John Harker – although he is just as much of a bonehead; and both Dr Sewards (Jose Soriano Viosca in the Spanish version) are equally uninteresting and ineffectual. And lastly – here, Martin the orderly is simply a big-mouth who butts into conversations, not the comic relief. And for that, my blessing upon everyone involved.

So, in the end, which version is better? Neither. Both have their virtues, both have their weaknesses. As different interpretations of the same story, both are fascinating to watch. The Spanish version, however, has the artificial advantage of novelty – and we thank Universal most sincerely for allowing us to see this treasure at last.

…and that opinionated Santo also has an opinion on this.

I’d like to see a movie about The Armadillo …. of DEATH!

LikeLike

…and I’m very disappointed there isn’t one already. What the hell, SyFy!?

LikeLike

They’ll combine it with a shark somehow, then make the movie. Possibly also a tornado.

LikeLike

Sharmanado?

Tornadillark?

Either way, I’m THERE!!

LikeLike

I like “Sharknadillo.” Maybe “Armanadark.”

Alternately, they could just make it really big and throw in another giganticized critter. Ultrapossum vs. Megadillo, perhaps.

We really need to stop giving The Asylum ideas.

LikeLike

Ultrapossum vs. Megadillo

WANT!!

LikeLike

Well, my killer armadillo movie will show proper respect for the source material. The armadillos were obviously imported from America at great expense (only a Transylvanian nobleman of the old school could afford such luxury), but when they were abandoned they had to fend for themselves. So they went scuttling around the crypts of the castle (which, of course, had collapsed when the Big D got staked) and ate strange things they found down there. Now, in 2017, a party of unlikeable teenagers is going camping on the old castle site…

(Incidentally, that first inn-yard scene looks remarkably like something out of a western. Did they have sets they could re-dress?)

LikeLike

I’m astonished that no-one has made that movie already.

Aww… Flesh-eating armadillos-ies!

I should say a redressed set was highly likely: all the studios were churning out westerns in the 20s and early 30s, including Universal (which is where the John Ford / Harry Carey westerns were made). Doesn’t take much to turn a stagecoach into a carriage!

LikeLike

Okay, now I need to write a screenplay for UvM. Of course, the scientist in said movie will be named Dr. Kingsley. I will also be sure to put “Inspired by”/”Dedicated to” credits in there for you.

LikeLike

“You made giant killer opossums and armadillos!? WHY??”

“I’m a scientist. That’s what we do. Also, they’re FRICKING ADORABLE!!”

LikeLike

“Oochie-coochie-coochie, little giant flesh-eating possies and dillies!”

“What the hell is wrong with you!?”

Oh god, I really want to do this.

I was thinking one each, Asylum-sized, so I could have a big-ass opossum eat a goddamn jet, but maybe Megapython vs. Gatoroid is the way to go, so there can be a pack of each. Although I will actually have the titular fight happen, dammit. And no ’80s pop singers. And my favorite B-movie actors in major roles, hopefully.

Lyz, who do you want to portray Dr. Kingsley?

LikeLike

Depends—is Dr Kingsley male or female??

Hmm… Unless my memory is playing tricks (not at all unlikely), there was a long-ago review in which I was casting myself. I think at the time I was toggling between Frank Langella and Louise Fletcher, but I could be mistaken. 😀

LikeLike

I don’t know if the comment system will show an image, so: https://firedrake.org/roger/images/possumplane.jpg

Sources: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Boeing_747-400 and http://www.aaanimalcontrol.com/opossumcar.htm

LikeLike

WordPress doesn’t let visitors post images, so I’ll have to do it for you:

“I call the big one ‘Bitey’!”

LikeLiked by 1 person

The comment system thinks my image is spam, I think. Let’s try again.

LikeLike

OK, I’ll just put in the link to it: https://firedrake.org/roger/images/possumplane.jpg

LikeLike

Dr. Kingsley’s gender…hmmm…well, if she’s a woman, I can make her first name something like “Robin” or “Pat” and roll out that lovable old chestnut, “But…you’re a girl!” On the other hand, I really like Frank Langella.

This should probably be your decision, seeing as how you’re the inspiration here.

Also, Roger’s image had me howling with laughter.

LikeLike

for the true Asylum experience, you also need an evil corporation that is planning on exploiting the animals, a traitor within the corporation who is selling info to the military (armadillos at war!), and a divorced couple (one idealistic, one who sold out and is now working for the corporation) who end up back together again (but only after the sell-out realizes how truly EEEvil the corporation is). You already mentioned the teenagers – I’d make them college students on a scavenger hunt (why? because it’s COLLEGE!) – one frat boy, one surfer/slacker dude, one football no-neck, one computer hacker, one queen bee mean girl, one goth girl, one cheerleader, and one sweet young thing. The computer hacker and the sweet young thing are the only ones who survive, and end up together.

Yes, I do spend way too much time thinking about these movies.

LikeLike

Even though the goth girl is the only one with a personality. Yes.

LikeLike

I have seen one example where the goth girl is the survivor: Trailer Park of Terror.

LikeLike

Speaking of The Asylum, I was just watching—well, not one of their productions, but one of their pickups—The Apocalypse.

If you’ve ever wanted to see End Of Days and The Rapture rendered on a budget that wouldn’t pay for your average backyard barbie, this is the film for you! 😀

(Circumstances forbid most of the other tropes, but you better believe we had a divorced couple back together again!)

LikeLike

I’ve seen that. Because I ordered the other Apocalypse where Sandra Bernhard is a space pilot, and got sent the wrong disk. (I think this was during the period when Blockbuster was trying to compete with Netflix at rental by mail.) What’s your excuse?

Once I got the correct Apocalypse, it turned out to be not worth having made two tries at, but I had to see for myself.

LikeLike

Only that my rental queue has been operational for so many years, I have no idea what’s in there any more, far less why. My best guess would be that the synopsis of The Apocalypse made it sound like a disaster movie rather than a Rapture film. (Also, I was much less well acquainted with The Asylum back then…)

LikeLike

I’ve been musing on a mini-run of Apocalypse/Rapture movies, due to catching a portion of Megiddo: The Omega Code 2 recently. I wasn’t aware of The Apocalypse, so I’ll put that on the list. Let’s see, that one, the Omega Code movies, Left Behind (although thanks to “The Simpsons” I can only think of it as Left Below)…the only other one I can think of is Holocaust 2000, but even if I could find it I’m not sure I’d want to brave it, as I recall Apostic hated it. Mmmm, maybe one more as I assume I won’t find that last one. Five seems about right…my last three mini-binges were all five movies long (slashers, the Zombi series, Christmas slashers) and that seems a good amount. Suggestions, of course, are welcome (unless Lyz wants me to stop the derailing of the comments, since I seem to have a knack for that).

LikeLike

Derail away. Oh, wait, you already have. 😀

LikeLike

Omega Code 2 is great for President R. Lee Ermey, but the opening moments of Omega Code 1 have Michael Ironside as (I hope) you’ve never seen him before. There’s Left Behind (2014), of course, but also the earlier three Left Behind films from Cloud Ten (2000, 2002, 2005, with Kirk Cameron but more importantly with Gordon Currie as the Antichrist, chewing scenery as if it’s Fat Tuesday). And then you’ve got the more obscure, and frankly disturbing, stuff: If Footmen Tire You, What Will Horses Do (1971, available on youtube), and the A Thief in the Night series (four films, starting in 1972). More details on Wikipedia.

Yeah, I may spend too much time on this stuff.

LikeLike

I’d forgotten about the Cameron Left Behind movies. I think I’ll stick with Nic Cage for now. I’ve seen Footmen, and yeah, that’s…something. The “Thief in the Night” series I’m not familiar with. Maybe I can dig up the first one for this.

LikeLike

therevdd: comment on any post at my blog (linked from my name here) and let’s talk by email.

LikeLike

Aw, don’t run away – where am I going to get anti-recommendations from!? 😀

LikeLike

Pingback: Dr Jekyll And Mr Hyde (1912) | and you call yourself a scientist!?

Pingback: Murders In The Rue Morgue (1932) | and you call yourself a scientist!?

This was on tonight, along with The Mummy, Creature from the Black Lagoon, and The Invisible Man. I was only able to stay awake through the first 3.

I squealed when I saw the Armadillo (of DEATH!) again. Reading the comments again, I really really want one of those movies to be made. Unfortunately, it’s too late to have Louise cast for it. She would have been great in it.

Just what does Van Helsing find in Rensfield’s blood anyways? Especially with the science technology available in 1931.

LikeLike

Having just watched 28 Weeks Later, in which Rose Byrne looks down an optical microscope to see viruses wiggling around…

LikeLike