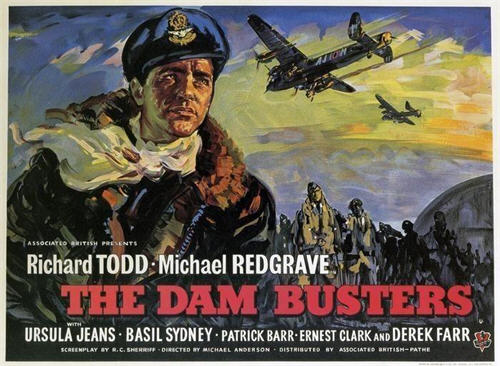

Director: Michael Anderson

Starring: Michael Redgrave, Richard Todd, Basil Sydney, Derek Farr, Ernest Clark, Patrick Barr, Ursula Jeans, Raymond Huntley

Screenplay: R.C. Sherriff, based upon the books The Dambusters by Paul Brickhill and Enemy Coast Ahead by Wing Commander Guy Gibson, VC

The Dam Busters recounts the true story of one of World War II’s more remarkable episodes: “Operation Chastise”, the destruction of the Mohne and Eder dams in Germany’s Ruhr Valley using the infamous “bouncing bombs” designed by scientist and aeronautical engineer Barnes Wallis (Michael Redgrave). The Ruhr Valley was Germany’s industrial heart, the hydro-electric power generated there driving the surrounding manufacturing complex, and its waterways used for transportation of both raw materials and finished products. An attack on the three huge dams that controlled this industrial centre had long been a dream of the British military command, and of Barnes Wallis in particular, who believed that such a strike would significantly shorten the war.

Knowing that underwater netting was in place to protect the dams from torpedo attacks, Wallace had initially tried to design a conventional bomb powerful enough to destroy the dams outright, but soon realised that the device would have to be so heavy, no existing plane would be able to carry it. An alternative, radical theory began to take shape in his mind: smaller bombs could do the job if they were dropped close enough to the faces of the dams so that the cushioning effects of the water – the very forces that would protect the dams from conventional bombing – could be made to work in their favour.

To get the job done, Wallis proposed to a startled RAF Command that they use low-level flying to skim a specially-designed bomb across the surface of the dam waters, arguing that if delivered at the correct altitude and speed, the bombs would skip across the water, stop at the dam face and sink to the desired depth to breach the wall. Initially, RAF Command responded to this proposal exactly as you might imagine; but Wallis persisted, and eventually managed to demonstrate that his theory was correct. Finally willing to believe that such a bizarre approach might actually work, the RAF put together “Squadron X”, the 617 Squadron of Lancaster Bombers, an elite outfit consisting of the very cream of Britain’s fliers under the leadership of Wing Commander Guy Gibson (Richard Todd). On the night of May 16th, 1943, the 617 set out for Germany with their experimental weapons…

The Dam Busters is a film divided neatly into thirds: the development of Wallis’s theory, and the move from theory to reality; the creation and training of the 617 Squadron; and the mission. Naturally, it is the first section of the film that is dearest to my heart – “Science!!” – although such pains did the producers take, that I am confident that lay-viewers will find it just as fascinating as I do. The Dam Busters opens in Barnes Wallis’s backyard, with the scientist using a jury-rigged catapult system to fire marbles across the surface of a small tank of water, his puzzled but intrigued children eagerly retrieving their father’s projectiles from various corners of the garden. (It should be mentioned that the producers somehow managed to resist the temptation of a “lost marbles” joke at Wallis’s expense.)

The film then follows the scientist as he battles endless red tape in order even to get the chance to even try out his theory; as he demonstrates that theory with great success; and as he suffers through the distress and humiliation of seeing test after test fail dismally. The development of the “bouncing bombs” was not an easy matter, and The Dam Busters makes no effort to disguise how close Wallis came to complete failure – nor indeed how much his ultimate success depended upon an almost suicidal heroism on the part of the men who would carry those bombs into Germany. Still, perhaps the moment that lingers most when The Dam Busters has finished is not any of the battle scenes, but the image of Barnes Wallis, shattered by yet another test failure, resignedly rolling up his pants legs to wade into the water of his test site in order to retrieve the fragments of his bomb and work out what went wrong this time.

Much of the success of The Dam Busters can be attributed to Michael Redgrave’s performance as Wallis; one all the more remarkable when it is compared to the actor’s far more famous role as the debonair Jack Worthing in Anthony Asquith’s adaptation of The Importance Of Being Earnest, made only two years earlier. The Dam Busters, in contrast, sees Redgrave grey-haired, bespectacled and cardigan-ed; a remarkable act of professional self-abrogation. There are moments, granted, when the characterisation teeters on the brink of cliché Absent-Minded-Professor-dom, but Redgrave’s beautifully judged performance never allows us to lose sight of the scientist’s essential humanity – and humility.

(He also gets the line of the film when, in response to an apoplectic official’s furious demand to know why on earth he should be lent a precious Wellington bomber at the height of the war in order to test out his idiotic theory, Wallis inquires diffidently whether the fact that he designed the planes in the first place would make any difference…?)

My praise of the first half of The Dam Busters, and of Michael Redgrave in particular, is not meant to denigrate the rest of the film, which is equally fine. It is evident just what pains the producers went to, to pay full tribute to the men involved in Operation Chastise, many of whom were destined to lose their lives. Guy Gibson was literally given his pick of all the men in the RAF when he came to form his team – something which, as you might imagine, went over like a lead balloon with the commanders of those squadrons plundered. (Fascinatingly, the first four men chosen by Gibson were “foreigners”: two Australians, a New Zealander and an American, prompting the semi-comic exclamation, “Hey, let’s not forget the British!”) As Barnes Wallis battles to complete his work on time, the men of the 617 practice low-level flying, overcoming such problems as inaccurate altimeters and a lack of appropriate bomb-sights – only to have Wallis break the unwelcome news that in order for his bomb to function properly, it would have to be released not from the expected height of one hundred and fifty feet, but from precisely sixty feet over the water. So they practice that.

The home stretch of the film follows the squadron in flight, approaching Germany from over Holland, and following a route pre-determined to bring them under only light fire. Of course, when you are being shot at, “light” is a relative term. Two of the planes are lost before the target is reached; six more will be downed before the mission is complete.

The battle scenes of The Dam Busters are a bit of a mixed bag. The photography and editing are very good, making clear just how difficult was the task that lay before the 617; but the special effects used to realise the destruction of the Mohne and Eder dams are a disappointment, even considering the film’s vintage. (A third target, the Sorpe, which was of a different construction, was hit but not breached.) However, The Dam Busters is one of those films whose intrinsic merits supersede its technical limitations – and has, over time, proved enduringly influential. Viewers coming to the film today with fresh eyes might find sections of it strangely familiar: The Dam Busters is one of the many – many – acknowledged inspirations for Star Wars, with sections of that production’s climactic battle scenes transferred over from their model with remarkable fidelity. Even some of the dialogue is copied!

Historical opinion remains sharply divided over the success or failure of Operation Chastise, particularly in view of the losses suffered by the British. In immediate terms, the mission certainly was a success; yet within a year, German industry was running again at full capacity. However, it is generally conceded that whatever its military shortcomings, the mission was a great success in terms of morale, raising the spirits of the British (granted, contemporary reports were very much exaggerated) while striking a blow at the complacency of the Germans, who had previously considered their heartland unreachable – hence the comparatively light defences on the dams. And indeed, one practical outcome to the mission was the strengthening of the defences of many inland targets in Germany, with men taken away from the lines in order to accomplish this.

But all this is wisdom after the event. One deeply significant aspect of The Dam Busters is that it offers, in the microcosm of Barnes Wallis’s story, a depiction of what scientists worldwide must have experienced during war-time: the moment at which their idea stopped being merely a fascinating theory, and became in truth the means of widespread destruction and the taking of human life. It is, of course, impossible to judge such matters in simplistic terms – there is no “right” or “wrong” way to feel, or to behave, in such a situation, let the individual react how he might.

It is, however, a fact that Wallis was devastated by the outcome of Operation Chastise, which saw over twelve hundred casualties in Germany – more than half of them, it was later discovered, Russian POWs – and the loss of eight British planes and crews. (Three of the fifty-six crewmen survived to be captured by the Germans; the rest were killed.) On Britain’s side, considering the way in which the 617 Squadron had been constructed, these losses represented a devastating blow to the RAF; and yet the notion of elite forces for specialist missions took hold. It is generally accepted that this attack on the Ruhr Valley gave birth to the idea of what today we would call the “surgical strike” – precision attacks on definite targets, rather than the use of carpet bombings.

Despite its losses, the 617 was re-built following Operation Chastise, and continued to fly these dangerous pin-point missions – eventually, indeed, using new bombs designed by Barnes Wallis who, despite his feelings of guilt and remorse, continued to cling to the idea of shortening the war, which had drawn him to military work in the first place. (With tragic irony, it would be during one of these later missions that Guy Gibson would lose his life.)

Historically, the screenplay of The Dam Busters does take a few liberties. The bombs we see used in the mission are round, not cylindrical; they are based on Wallis’s earlier designs, before his realisation that he would have to remove the bombs’ casings to get them to function properly. There is a simple enough explanation for this: in 1954, the real bombs’ design was still classified information. Wallis himself is depicted as a lone wolf, wholly responsible for the scientific side of the bombing project, whereas in reality he had a team of technicians who made significant contributions to the project. Conversely, the film does have Wallis declining to claim sole ownership of the “bouncing projectile” idea, chalking it up instead (and, I believe, truly) to observations made by Horatio Nelson with respect to his cannon-fire sinking of an enemy ship.

(On the other hand— Call me a cynic, but I somehow question whether Nelson did in fact describe the French as being, “Dismissed by a yorker”. [And yes, I know there are some of you out there who don’t know what a “yorker” is. Neither did the French, and look what happened to them.])

The film’s one egregious mis-step comes when it has Guy Gibson coming up with the idea of how to overcome the altimeter problem – while watching a kick-line at a music hall! In truth, the use of fixed beams of light to determine the altitude of a plane had been developed during World War I. As for the rest of the film, some of its events have been—not altered, precisely, but sanitised. As portrayed by Richard Todd, Guy Gibson is an ideal officer, courageous and self-sacrificing in the air, protective of his men and popular on the ground. Sadly, this seems not to have been entirely the case. While no-one would dare question Gibson’s abilities in the air, it seems that on the ground he was anything but popular, being cold, aloof, and rigidly class-conscious. (In Gibson’s defence, in a recent documentary the woman who acted as his driver at the time of these events advanced the scornful opinion that he was “too intelligent to be popular”, which has a nasty ring of truth about it.)

The film’s other piece of fudging concerns the treatment of Gibson’s outfit by the men of the other squadrons, who were still flying routine missions while the 617 was undergoing its training. In The Dam Busters, the clashes between the two factions are depicted as nothing more serious than a bit of good-natured ragging; something resolved by a few timely mess-hall debaggings. In reality, the open hostilities that arose between the combat fliers and the 617 over the latter’s removal from active duty was a serious problem, hugely detrimental to morale.

Despite these tamperings, The Dam Busters is as historically accurate as, perhaps, we have any right to expect such a production to be. Of course, when dealing with a film of this nature one must always distinguish between its qualities as history and its qualities as cinema. There are few doubts about the latter. The Dam Busters bears a warranted reputation as one of the great British war films – and is made all the more interesting by its overall tone. There is no question that there was a wide attitudinal difference between the war films produced in Britain and those produced in the United States, particularly those made during the actual time of the conflict. The reasons for this are debatable. Difference in cultural temperament accounts for some of it; the “vetting” of American films by the Office of War Information for some more. (OWI nursed a strange delusion that the forced insertion of lengthy speeches explaining “Democracy” and “What This War Is About” into screenplays would “gently propagandise” [their term] the American public without it being aware of the process.)

The most significant factor, however, is undoubtedly the fact that the war hit the British civilian almost as hard as it did the British armed forces. Consequently, there was little room in the films of the era for speeches, or kind lies, or platitudes; the people had seen too much, and suffered too much, to put up with that. It was not until the highly unpopular Korean conflict that the tone of American war films began to shift, becoming more questioning and ambiguous. British films, devoted as they were to celebrating the heroism of their people, had always had such undertones; and The Dam Busters lies firmly within this tradition.

Although the film, as it stands, tells the story of a military and technological triumph, the hard questions asked about Operation Chastise after the event were beginning to cast a long shadow. The Dam Busters ends on the bleakest, most downbeat note imaginable. No celebration here; no speeches; no flag-waving. Instead, we conclude with a pan around the mess-hall, showing the places set for the men who would never return; with shots inside the deserted rooms of some of the casualties; with Barnes Wallis in tears (“All those boys! All those boys!”); and with Guy Gibson going sadly to his quarters to “write some letters”. The audience itself is left to confront the unanswerable question of what, exactly, constitutes an “acceptable loss”.

For all its merits, The Dam Busters is not much screened these days; not because of the continuing disagreements over the success or failure of Operation Chastise, but rather because shifting social mores have made the film something of an embarrassment. One of the key subplots of The Dam Busters involves Guy Gibson’s beloved dog, which unhappily was run over and killed on the very eve of the historic mission. As a tribute to his pet, Gibson requested that its name be used as the codeword to signify the successful destruction of the German dams. As it happens, however, the name in question is a word that has since become socially unacceptable in the extreme: the dog was a black labrador, and its name was “Nigger”. (Watching this film with an unprepared modern audience is a fascinating experience: you just sit back, and listen to the sound of jaws thudding into the floor…) The casual and repeated usage of the animal’s name throughout the film is jolting, and becomes almost surreally so when the radio operator receives news of the mission’s success, and responds by shouting gleefully across the room, “Sir! It’s Nigger! It’s Nigger!”

Appalling as this word usage may seem to modern sensibilities, it is evident that no conscious malice was intended either when Gibson named his pet, or when the film was made – which is precisely what makes it so difficult to cope with. Contemporary films in which the word was indeed used with malice – the vitriolic tirades of Richard Widmark’s character in No Way Out, for example – are easier to accept simply because we are given a context in which to deal with it. In The Dam Busters, it’s simply – there. This subplot serves as a salutatory lesson of just how deeply ingrained in British society of the time was a racist mindset, all the more so since the guilty parties here are otherwise so entirely “nice”.

Changes in social conditions over time have led to The Dam Busters becoming something of a hot potato, with the film suffering censorship in most parts of the world; when, that is, it is screened at all. In Britain, the contentious material was often cut out altogether, leaving the latter portions of the film disjointed and confusing. In the US, more sensibly, the offending word was simply overdubbed. At the present time, Australia is one of the few countries where The Dam Busters continues to be screened intact. Whether that says good things about us or bad things, I haven’t quite been able to decide.

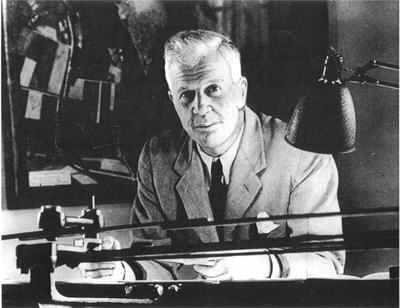

Sir Barnes Wallis

I bought the DVD of this film after reading your review of it some time ago, and I dearly love this movie. War movies are one of my special interests, and often British war movies are some of the best. They seem to combine the historical interest, the feel for the times, the often exciting action, and a real acknowledgment of the price of war. An acknowledgement that ( as you noted) American films sometimes lack.

I do think Barnes-Wallace’s scenes are absolutely fascinating, the science, the frustration, the striving to achieve a result that could hopefully shorten the war, all very compelling. I ask myself why I’m so fascinated by military history, technology, and the rest. I’m a pacifist in my life, and I hope that we will learn as a species to find a way other than war. But, I build models of war machines, and play wargames with miniature soldiers. I think this film especially is a good look at that duality. The striving and achieving of the weapon and the skills to use it, the camraderie of the people, the challenge of training, the triumph of the mission, and the terrible loss on both sides. To have a film be a technical triumph, an exciting story, an accurate history, *and* to make us think of what it all means and if it was worth the costs – not many films accomplish all this.

I wonder about Guy Gibson – RAF Wing Commanders aren’t really known for charm, are they? I would think in Bomber Command especially, if you didn’t distance yourself somewhat from the men, that you might go insane watching friends die because of decisions you were making.

I was quite amazed and amused at first viewing, how much of the dialogue and indeed the whole Dam bombing sequence, shot-for-shot, was used in ‘Star Wars’. As much as I enjoy ‘Star Wars’, I love history more.

As for the name of Gibson’s dog, I’m of two minds. I hate that we’ve virtually lost this movie because of that word, but I’m also someone that is often the target of hateful slurs about my sexuality, and I can totally relate to not wanting to hear slurs casually used. Indeed, I almost can’t get through “Generation Kill” anymore because of all the slurs against LGBTs that are used by the Marines in the book and the series. I don’t know what the answer should be. I’d prefer thoughtful discussion and acknowledgment of history, but there are so many people that use the usage of slurs in books, music, and film as an excuse to engage in further abusive acts. 😦

Thank you Liz, for this insightful review and for introducing me to this superb film. 🙂

LikeLike

The “scientific” WWII film that always fits next to this in my mind is The First of the Few, so I’d recommend taking a look at that too.

If you search “dam busters star wars” on YouTube, you should find a pair of videos by “HenryvKeiper”, each of which uses video from one film with dialogue from the other. Recommended. (I won’t post links or the automatic spam spotter will make more work for Lyz.)

Personally I prefer to keep the original soundtrack and, if people are likely to be offended, preface or follow the showing with “this was made in 1954, when that sort of language was entirely acceptable; not all racism is like Those Guys you’d cross the street to avoid”. But then I read John Buchan or Dornford Yates by trying to put myself into a mindset for the era, not by constantly saying “oh what an entitled ass this hero is”.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I don’t think The First Of The Few has ever turned up here—thank you for reminding me of it.

Yes, I completely agree about not censoring the film. In a way the casual British racism is even more confronting than the historically loaded American kind, just because it was all so taken for granted, and yes, so firmly associated with the “nice” people.

I read a lot from the 20s and 30s too…and get to deal with the sexism as well as the racism, fun!! 😀

(One of my personal side-projects is trying to figure out when writers stopped having their heroines faint at the slightest provocation; haven’t found the point yet…)

LikeLike

Thank you for that, it’s great to hear.

I think it’s important to balance the message that, This is unacceptable with the reminder that, This is how things were. Reactions to The Dam Busters are always fascinating because, clearly, people do not realise today how casual and blatant societal prejudice used to be—and that’s great—but it creates a different problem, namely, people not always understanding what the issue is—the “Oh, they’re just words” brigade. No, they’re not: they’re the thin edge of the wedge of violence, and once you allow verbal and emotional violence, physical violence becomes so much easier…

As for your hobbies—being fascinated by something doesn’t mean you condone it; any more than loving horror movies means you’re going to go out and kill someone (sorry to break it to you, BBFC!), or an interest in forensic investigation means you don’t see how terrible the crime is.

Your comments about Guy Gibson make me think of Twelve O’Clock High, wherein first Hugh Marlowe and then Gregory Peck cracks up under the strain of commanding a flight squadron. (And which is one of that first crop of American war movies to show that shift in attitude.)

LikeLiked by 1 person

Lyz, thank you sincerely. 🙂

RE: ‘Twelve O’Clock High’ – that’s another favorite of mine, mainly because as you note it’s one of the first American war movies to try and show the strain & price of war. Another I enjoy is ‘The War Lover’. Steve McQueen plays the commander of a B-17. I think it’s the role that the awesome McQueen is the hardest evers to like. Anyway, I’d like to read Gibson’s book, and try to learn more about him.

Yes, an attitude of “this is way people behaved, but the racism/sexism/other is still *wrong*, even when heroes acted that way” is a good way to proceed. 🙂 I think everyone needs to examine why & how we dehumanize others, and then hopefully we will all resolve to do better. I think often of Sir Patrick Stewart’s line from a powerful episode of ‘TNG’ – “When children are taught to devalue others, they can learn to devalue *anyone* – including their parents.”

LikeLike

I’m not familiar with The War Lover – I’ll put it on The List.

I have another Patrick Stewartism for you:

“But she, or someone like her, will always be with us, waiting for the right climate in which to flourish, spreading fear in the name of righteousness.”

LikeLiked by 1 person

🙂 Indeed. I don’t mind telling everyone that TNG got me through an abusive childhood, and that Captain Picard is more a father to me than that man with his name on the paperwork. I hope someday I can tell Sir Patrick that in person.

‘The War Lover’ is quite excellent, McQueen plays a callous, fearless, misogynistic pilot. I usually think of MxQueen as Mister Sexycool, but not in this one.

LikeLike

Isn’t a yorker a cricket term–a way of pitching the ball, like a googly? (Although I don’t know what either means in terms of what the ball actually does).

You can run into surprising casual racism, as well as antisemitism, among nice British people if you get hold of an early edition of an Agatha Christie or Dorothy Sayers mystery from the 1920s or ’30s. Obvious example is the original title of “And Then There Were None” but there are also words and expressed attitudes in other stories that are changed or completely removed in later editions.

LikeLike

A yorker is a fast ball delivered low and on the full, just at the conjunction of the crease, the bat and the foot. It requires a precision response from the batsman—otherwise he may be bowled or out LBW—or at the very least in a great deal of pain. (Yorkers are known here as “sandshoe-crushers”.)

Oh, yes, very familiar with all that—that’s where most people know it from these days. (It’s also notable that their anti-Semitism is much more hostile that their general racism.) The scary thing is, those two are amongst the milder examples of the phenomenon.

LikeLike

One of the many reasons why Dorothy Sayers is better than Agatha Christie is that Wimsey may use the racist language of the time, but he clearly doesn’t approve of it.

LikeLike

But it’s not a simple matter of “This person’s attitude is better than that person’s attitude”, and none of it has anything to do with their writing. As far as that goes, Sayers is more blatantly anti-Semitic; while Christie uses Hercule Poirot to mock the British attitude to “foreigners”, including his wonderful speech in Peril At End House when he reveals that he deliberately uses poor English when he wants to lure suspects into a false sense of security. In both cases we just have to deal with it in its context.

LikeLike

I may have poor data because I have read a much smaller proportion of Christie than of Sayers.

LikeLike

Dorothy Sayers seems to have the peculiar idea that Jewish people talk like Daffy Duck, The lisp is used in more than one novel as a kind of code identifier for “those people.”

LikeLike

That is a very long-standing British stereotype (Agatha does it too) that I have tried before now to hunt to its source—it seems to have been set in stone by the first stage adaptation of Oliver Twist, but obviously was already recognisable to the public before that. It may have been a mutation of an earlier European stereotype that insisted Jewish people “hiss”—possibly just the way Hebrew was heard. But it also seems to be mixed up with the idea that gay men lisp—in both cases implying an absence of traditional masculinity. There was a parallel anti-Semitic stereotype that Jewish people were sexual deviants, and so it may be a “politer” signifier for that.

LikeLike

Only four or five years ago, I saw “The Dam Busters” with its original soundtrack on Turner Classic Movies. It’s interesting to note that destroying dams is specifically named as a war crime by the Geneva Convention. Well, you can’t make an omelet without breaking a few eggs, as Stalin said to Molotov.

LikeLike

Yes, the disproportion of civilian casualties led to the banning of dams as targets; this was one of the cases cited.

LikeLike

Correction – Barnes Wallis did not design the Wellington – he designed the geodesic frame of the fuselage

LikeLike

No doubt you are right about that, but you’d have to take it up with R. C. Sheriff. 🙂

LikeLike

I had a Dutch friend, now deceased, whose uncle was a slave labourer in one of those Ruhr factories. He was one of the lucky few who managed to climb to the factory roof when the wall of water came roaring down. The Nazis left them sitting there for four days before they rescued them. Incidently, Guy Gibson was sent on a bond tour of Canada afterwards, and dated my cousin Jeanne, who was a very pretty girl, when he was in Toronto. She had a photo of the two of them.

LikeLike