[Original title: Le Voyage Dans La Lune]

Director: Georges Méliès

Starring: Georges Méliès, Henri Delannoy, Victor André, Bleuette Bernon, Jehanne d’Alcy

Screenplay: Georges Méliès, based upon the novels of Jules Verne and H.G. Wells

Foreword: When Georges Méliès’ epoch-making science fiction film, Le Voyage Dans La Lune, was first screened in 1902, it was made available to exhibitors in both black-and-white and hand-coloured prints. Although, as a consequence of Méliès’ business naivety and the dishonesty of others, the film itself was soon effectively in the public domain, and while it has been almost constantly in circulation from the time of its initial release, the coloured prints were for many decades considered lost. However, a copy resurfaced in 1993, in Spain, when a private collector donated a print to the Filmoteca de Catalunya. Initial excitement turned to dismay when it was released that the print was so damaged by decomposition, restoring it would be an impossible task.

But there’s nothing that some people like better than a challenge. A deal was struck between the Filmoteca de Catalunya and the film preservationist Serge Bromberg. The film was first transformed from a solid, twisted lump of melted celluloid into an actual film strip via treatment with certain chemical vapours (a process developed by Bromberg and his team, the details of which they decline to divulge), before the incredibly slow and painstaking task of preserving by digitisation every single frame of the film could begin. This done (with backing-up and separate-site storage to a degree which may well be imagined), the images sat and waited a full eight years for the technology to complete the next step in the process to be developed.

Then, with funding from the French organisation, the Groupama Gan Foundation for Cinema, and the Technicolor Foundation for Cinema Heritage, the individual images were transformed back into a motion picture. Bromberg and his team met their goal of having the project finished in time to mark the 150th birthday of Georges Méliès; and in 2011, at the Cannes Film Festival, a colour print of Le Voyage Dans La Lune screened for the first time since 1902.

****************************************************

Synopsis: At the meeting of a society of astronomers, their head, Professor Barbenfoullis (Georges Méliès), astonishes his colleagues by proposing the building of a rocket in order to undertake a journey from the Earth to the moon. An uproar results. One of the astronomers vehemently opposes the proposal, and Barbenfoullis responds by throwing his papers at his colleague’s head. After order is restored, it is resolved that the journey will be undertaken, with five of the astronomers volunteering to accompany the Professor. A rocket is constructed, and the enormous cannon required to launch it is forged. The astronomers board the rocket to the acclaim of the gathered crowd, and at the conclusion of a formal ceremony, they are fired into space. The rocket lands roughly but safely, and the astronomers look around in astonishment at their surroundings, and at the Earth, which rises into the night sky. After being shaken by an unexplained explosion, the astronomers settle for the night, but they are soon woken from their dreams of celestial bodies by a fall of snow. Retreating into the interior of the moon, the explorers discover an extraordinary world populated by mysterious and dangerous beings…

Comments: What today we might call “the language of cinema” can be attributed to no one individual, but represents the culmination of various technical and artistic advances that permitted the birth of the moving picture towards the end of the nineteenth century. Understandably, what we are now able to recognise as momentous steps forward tended to occur in a fairly discrete manner, fuelled by the particular preoccupations of the individuals involved. A number of the most significant contributions that accompanied the dawning of the cinematic age emanated from France; and, curiously, the most important of these could hardly have been more philosophically opposed.

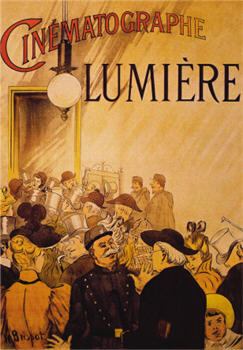

In 1894, Auguste and Louis Lumière patented their cinématographe, a device incorporating a camera, a developing system and a projector all-in-one, and the following year began advertising their invention to the public via the screening of short films recorded with the equipment. In the sense that the Lumières’ films – including those most historically imperative of simple narratives, La Sortie Des Usines Lumière and L’Arrivée D’Un Train En Gare De La Ciotat – were recordings of the daily doings of people and places, there is a tendency today to regard the brothers as documentary-makers. However, in truth the Lumières regarded their films merely as means to an ends, as the most effective way of selling the invention in which they were primarily interested as a technical breakthrough.

The Lumières’ invention was by no means the first such device patented, and nor were they the first to show short films to the public. They were not even responsible for the term “cinématographe”, which was coined by their compatriot Léon Bouly two years earlier, to describe his own patented device for “the analysis and synthesis of motions”. However, Bouly was unable to exploit his invention, and when his patent lapsed the Lumières appropriated both the term and the idea – significantly improving upon the latter, at least. What the Lumières could boast of their version of the device, as their predecessors and rivals could not, was genuine practicality of operation; ultimately, it was their technical superiority, rather than any artistic vision, that won for the brothers their place in the time-line of cinema.

Despite this, in the Lumières’ work the viewer can truly see the motion picture taking its very first baby-steps. Simple as the films themselves are, within them one can observe their makers’ recognition of the impact of such concepts as camera angle and depth of shot. Much of the power of L’Arrivée…, for example, lies in the decision to place the camera at the very edge of the railway platform, allowing the approaching train to loom up and overwhelm the image. However, when all is said and done, the Lumières were inventors, not film-makers; cinema attracted them not as an entity in and of itself – still less as a potential art-form – but purely as a technical problem that needed solving. Less than six years after their epoch-making Parisian shows, the Lumières had ceased to make films.

But there were others ready and willing to snatch up the cinematic banner as it fell from the Lumières’ hands – although ironically, cinema’s next movement forward would be the work of a man whose vision was to use it to preserve the conventions of the theatre. A Parisian by birth and a manufacturer of shoes by intention, the young Georges Méliès took an entirely unfair advantage of his father’s decision to send him to England to improve his grasp of the language prior to entering the family business, spending countless nights at theatres both high- and low-brow. Whatever he may or may not have learned about use of the local vernacular, Méliès conceived a passion for illusion, and to his family’s disgust finally devoted himself to the study of stage effects and magic, supporting himself as he learned as an illustrator and cartoonist.

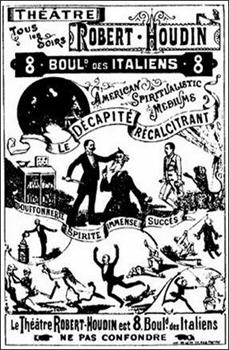

Upon the retirement of his father, Méliès used his share of the family business to purchase the Robert-Houdin Theatre (named for the man considered the father of modern stage magic, and in tribute to whom another famous performer would devise his stage name) and began a triumphant period as a professional illusionist. So successful was Méliès in this new role that in 1895 he found himself one of the celebrities invited to attend the Lumieres’ premiere of their short films at the Salon Indien du Grande Café in Paris.

The impact of these “moving pictures” on Méliès was incalculable; and when Auguste Lumière subsequently refused to sell him a cinématographe, Méliès responded by contacting English inventor Robert William Paul and buying one of his, a device based upon Thomas Edison’s “Kinetoscope”, with which the first British film, Incident At Clovelly Cottage, was shot. Méliès made his own modifications to Paul’s device, not in order to enter the battle for technical predominance, but with a view to incorporating film into his stage performances.

Whether it is due to modern sensibilities or to the accident of fate that preserved some of Georges Méliès films and not others, there is a tendency today to regard Méliès as the father of cinema fantastique. While there is certainly some truth in this, in fact Méliès made all sorts of films, with Lumière-like documentaries, operatic scenes, historical narratives and staged newsreels among them.

(“Staged” not in the pejorative sense: it was the practice at the time for film-makers to “imagine” events at which no camera was present, for the gratification of the public. Méliès’ success over the next few years would be such that in 1902 he was invited to stage a version of Edward VII’s coronation which, due to the king-in-waiting’s illness, was actually completed before the real thing happened. Indeed, this film is highly unusual for its incorporation of real footage of the pre- and post-coronation parades, added prior to its delayed release.)

An anti-authoritarian streak also prompted Méliès to make films criticising or satirising public figures, and to dabble in dangerous political waters: his series of films on the Dreyfus affair were suppressed by the authorities, who feared that their screening might incite civil unrest.

On the other hand, the same authorities made no objection to productions such as Après Le Bal, in which Méliès became one of the first directors to sell a commercial film on the strength of its (implied) nudity.

The critical moment of Méliès’ career, however – so we are told, although the story might well fall under the heading of too-good-to-be-true – came when his camera jammed while he was filming a street scene. When he later inspected the “ruined” footage, Méliès made a startling discovery: he had captured miraculous images of a taxi turning into a hearse, and of a man turning into a woman; while other entities, people and objects alike, both appeared and disappeared.

This revelation was to shape Méliès’ film-making; and over the next few years he would turn out an incredible stream of fantastic films featuring not merely jump-cut effects, but also such pioneering techniques as dissolves, overlaps, double-exposures, superimposition, matte shots, and even a primitive kind of zoom achieved by anchoring the camera and moving the object closer to the lens. The possessor of a gruesome sense of humour (or perhaps just a peculiarly French sensibility), Méliès’ stage illusions had often centred upon decapitation and other forms of dismemberment; and this became a frequent theme of his films, as well, in productions such as L’Homme À La Tête En Caoutchouc, which features a scientist performing macabre experiments and climaxes with an exploding head. (This, in 1901. Take that, David Cronenberg!)

Initially, Méliès had indeed used his films as part of his stage-show, but in time the films themselves became his professional focus. Over a period of six years, Méliès’ imagination gave birth to an incredible stream of wildly creative short narratives, among them some of the earliest examples of what we would now call fantasy, horror and science fiction.

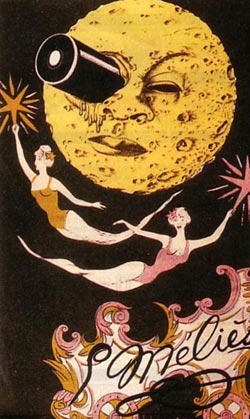

In 1902, Georges Méliès was at the very pinnacle of his success, and for his 400th film undertook the most elaborate and expensive production he had yet conceived: an audacious melding of two of his main influences, Jules Verne and H.G. Wells, called Le Voyage Dans La Lune. Costing an incredible 10,000 francs, taking months to complete – including the construction of the sets and costumes, all done especially for the film – at a time when a week was considered an excessive, and running fourteen minutes when most films were less than three, Le Voyage Dans La Lune was an extravaganza.

All this was a huge risk, but in Méliès’ judgement, a justifiable one – and purely in terms of his film’s reception he was quite right. Sadly, however, as we shall see, it was this film’s success that signalled the beginning of the end for Georges Méliès.

Le Voyage Dans La Lune opens with the gathering of a group of astronomers who, amusingly, are clad in wizards’ robes, and who proceed to entertain us by magically converting the telescopes that they are handed by a series of page boy-attired female attendants into folding stools, on which they seat themselves. (These ubiquitous girls, who reappear performing various functions throughout the film, were ballet dancers from the Theatre du Chatelat, still operating today as a forum for opera and concerts.) The leader of the astronomers then enters, bowing dramatically as he approaches the podium. This is Professor Barbenfouillis, played, as was his wont, by Georges Méliès himself. The Professor steps up and makes an extraordinary proposition: that of a journey from the Earth to the moon by rocket. The result is an uproar, during which one of the astronomers threatens Barbenfouillis with violence, and Barbenfouillis responds by throwing a handful of papers at his opponent’s head.

It is, I may say, entirely typical of Méliès that the astronomers should behave like a group of unruly children: scientists were always one of his favourite targets for satire, even when, as here, they are essentially the heroes of his tale.

A word here on the presentation of this film: those internet versions of Le Voyage Dans La Lune that have a narrator explaining the action are more right than perhaps they know. Méliès did not use intertitles on his films, which for the most part were self-explanatory. Instead, he would provide in his theatre (still the Robert-Houdin, converted for the projection of film) a catalogue listing the various scenes, rather like the chapter menu on a DVD today.

However, on those occasions when the narrative was a bit more complicated, as here, or where he wanted to be certain that the audience would grasp the point of a story, Méliès would indeed arrange for a narrator to provide a live verbal explanation while the film was being projected; not infrequently, he would perform this task himself. It is from Méliès’ notes, prepared for this purpose, that we know that his character’s name is Professor Barbenfouillis – otherwise, “Professor Beard-Tangle”; it has been suggested that the name is a comical corruption of “Barbicane”, the name of Jules Verne’s anti-hero of From The Earth To The Moon.

When order is restored, five of the astronomers volunteer to accompany the Professor to the moon. (For the record, the other five travellers are called Nostadamus, Alcofrisbas, Omega, Micromegas and Parafaragamus.) The page-girls reappear with their explorers’ wardrobe: ordinary street clothes! The six intrepid adventurers bid their Earth-bound colleagues farewell and make their way to a workshop, where skilled technicians of all kinds complete the construction of the rocket.

It is at this point that the scope of Méliès’ imagination really becomes apparent – as well as his devotion to the conventions of the theatre, a tendency that has seen him criticised for his “anti-cinematic” stance. It is true that Méliès’ films are invariably shot with an unmoving camera, with the objects before it being manipulated in order to create the shot; it is likewise true that his films – and Le Voyage Dans La Lune is a perfect illustration of this – are composed of a series of static tableaux, with the actors performing in front of painted backdrops and sets constructed of papier-mâché, as on a stage.

But as this film wonderfully illustrates, the effect of this can be magical. The care and the attention to detail that Méliès and his team put into the construction of the sets for Le Voyage Dans La Lune are staggering. Whatever we might make these days of its simple narrative, visually the film is breathtaking. Here, the construction of the rocket gives way to the rooftops of – Paris? – as Barbenfouillis and his followers observe the casting of the enormous cannon that will shoot them to the moon. The illusion of depth in this shot, and in the subsequent scene of the rocket’s launch, is marvellously executed. The explorers point and exclaim in the foreground as molten metal is poured into a huge mold in the background, with steam belching forth to engulf and hide the surrounding buildings.

Next, the travellers bow and wave to the gathered crowd (which “crowd” we are obliged to take on faith) before climbing into the rocket. It is sealed, and the page-girls thrust the rocket into the cannon. A ceremony is performed and a soldier signals with his sabre. The cannon, which seemingly projects almost endlessly into space, is fired, and the explorers are on their way.

We then observe the moon as it seems to come and closer; this was the effect achieved by moving the model moon closer to the camera between shots. As for the moon itself, it is a representation of a famous fairy-tale character: the unmistakably human features of The Man In The Moon grow ever more distinct as the travellers rapidly approach their destination – and then the rocket plunges into his right eye.

So indelible is the resulting image, so defining the moment, not merely for science fiction, but for cinema in general, that it is easy to overlook the technical significance of this sequence, in which Méliès chooses to show the landing twice, from two different perspectives – once the fantastical, once the realistic, as we cut away from The Man In The Moon grimacing with pain (understandably!) to the rocket embedding itself in the surface of the moonscape.

This narrative doubling was an unusual effect at the time, and it made an impact. One of those influenced by it was pioneering American film-maker Edwin S. Porter, who began to experiment with similar techniques in his own films. The irony here is that Méliès is often compared unfavourably with Porter, who is credited with developing many of what might be regarded as the “real” cinematic techniques, particularly continuity editing, and for his understanding of the critical role played by “the shot” in cinema (as opposed to “the scene”, all-important in the theatre). Before gaining the opportunity to develop this new cinematic language, however, Porter cut his professional teeth making short trick films for Edison, most of them drawing heavily upon pirated versions of Méliès’ own films.

Once safely landed, the travellers climb out of the rocket and gaze around in awe at the surrounding moonscape. (No worries about atmosphere or gravity or “other science facts” here.) Mysteriously, the rocket then vanishes, something which seems to cause the travellers no particular concern. They – and we – are then treated to another astonishing sight: that of the Earth rising into the sky above the moon.

Here again Méliès creates a legacy for the ages. When science fiction came into its own during the 1950s, there was hardly a space exploration film made that refrained from including an “Earth-rise” shot. The most famous example of these is probably that found in Destination Moon, and rightly so: the scientific and technical accuracy of that film is justly famous.

Amusingly, we notice another convention here that would be passed on to the generations to follow: few space travellers have ever gazed back at anything other than their own particular corner of Planet Earth. In most cases this means that we are given a lingering view of the Americas; Barbenfouillis and his companions, conversely, are rewarded with the sight of Europe and Africa – which, considering that within the narrative frame of this film, the journey to the moon took no more than minutes, is probably fair enough. Otherwise, only Destination Moon, devoted to the reality of space exploration, managed to resist the lure of this particular form of chauvinism.

Before the travellers can begin to explore, they are flung to the ground by a violent explosion – a moonquake? Worn out, they then settle down for the night; and as comets pass overhead and stars appear in the sky, their dreams conjure up other kinds of celestial bodies: first the stars take on women’s faces; then two other young women appear, holding up another star, while the goddess Phoebe perches coyly on a crescent moon. (An elderly man also appears, emerging from within Saturn, but I’m not prepared to suggest which of the travellers dreamt up that image.) Annoyed by the presence of the travellers, Phoebe waves her arm, and snow begins to fall, covering moonscape and travellers alike.

(Amongst the celestial women is Jehanne d’Alcy, who many years later would become the second Mrs Méliès. She was also the star – the cinematic kind – of Après Le Bal.)

The travellers awake to find that the snowfall, at least, is no mere vision. Shivering with the cold, they retreat into an underground cavern…and here we exchange From The Earth To The Moon for a sliver of Journey To The Centre Of The Earth, as the travellers discover a world full of strange rock formations, waterfalls, and enormous mushrooms. Barbenfouillis plants his open umbrella beside them to gauge their size, only to have it turn into a mushroom, and soar towards the cavern roof. (You may insert your own ’shroom joke here.) The next instant, we move from Verne to Wells as one of the moon’s inhabitants, a Selenite, approaches the travellers with contorted movements, handsprings and somersaults. (The Selenites were played by acrobats from the Folies Bergère.) Barbenfouillis confronts the creature and strikes at it with his umbrella – and it explodes, going up in a large cloud of smoke.

And here we would seem to have another defining moment in the history of science fiction; one that, oddly, always puts me irresistibly in mind of the “Dawn Of Man” sequence from 2001. What it is about Homo sapiens, that those imagining tales of his achievements so often feel compelled to include someone or something being killed?

More Selenites emerge, and finally the travellers are overwhelmed by their sheer numbers. Bound, they are taken to the throne room and shown to the Selenite king. Barbenfouillis manages to break free and, seizing the king, throws him violently to the ground where he, too, explodes. With the Selenites momentarily frozen with horror, the travellers make their escape, fleeing across the moonscape to their rocket, now inexplicably perched on the edge of a cliff. (I wonder whether Méliès originally planned a sequence where the travellers moved the rocket to its new launch area, then decided it wasn’t necessary?)

As his companions climb in, Barbenfouillis fends off some pursuing Selenites before climbing down a rope now attached to the front of the rocket. His weight tips the rocket over the edge, and it is “launched”, falling towards the Earth. As the Selenites gesture furiously, one Selenite, unbeknownst to the travellers, is perched upon the tail of the rocket…

The rocket plunges into the ocean, and we get another of Méliès’ wonderful creations, this time a seascape partially artificial, and partially the result of shooting through an aquarium containing fish and what appears to be some agitated axolotls. The rocket is discovered and towed back to land by a passing steamer.

For decades prints of Le Voyage Dans La Lune ended here, with the final sequence, in which the travellers are publically lauded for their accomplishments, believed lost; but the restored colour print contains this long-unseen sequence, which is chiefly notable for an almost thrown away shot in which a startled bystander is shown struggling with that unaccounted-for Selenite. The film proper, however, concludes with the ubiquitous chorus joining hands and dancing around a statue of Professor Barbenfouillis…a semi-comic rendering of Georges Méliès himself.

Le Voyage Dans La Lune was every bit the success that Méliès anticipated – and ultimately, too successful for its own good. Throughout his career, Méliès was plagued by piracy of his work, and by his inability to find business partners willing to deal with him equitably. For a time, Méliès’ films were distributed in America through the American Mutoscope and Biograph Company, but at length Méliès became dissatisfied, and rightly, with their handling of his affairs.

Determined to take his financial arrangements into his own hands, Méliès sent his brother, Gaston, to America to set up a branch office through which Le Voyage Dans La Lune could be distributed – but by the time that was done, it was already too late. An employee of the Edison Company had stolen a copy of the film in Europe, and by the time Méliès was ready to offer the film himself, pirated copies of it were all over America, earning a fortune for Edison and his company.

Having invested so much in the production of his film, Méliès had no resources left for mounting a legal battle against the powerful and wealthy Edison. It was a blow from which he never recovered, either emotionally or financially. The final straw came when another American pirate, Sigmund Lubin, unknowingly offered to sell Méliès a copy of his own film – and then reacted to the anger and misery of the outraged film-maker as if it was simply a very good joke.

It might have been some consolation to Méliès had he known that more than one hundred years later, his name would be celebrated, and his work one of the undisputed landmarks in the history of the cinema; that his vision of The Man In The Moon with the rocket in his eye would come to be used as shorthand not just for the science fiction film, but for the dawn of cinema itself. It is an image deeply embedded in the collective consciousness, aided of course by organisations like Turner Classic Movies, which frequently employs it, but chiefly by virtue of its sheer ability to stir the imagination.

A Futurama reference to this iconic visual was certainly inevitable; a better indication of the extent to which popular culture has absorbed the creative output of Georges Méliès may be found in the Smashing Pumpkins’ video for “Tonight, Tonight”, which features a human-featured moon, umbrella-bearing space explorers, exploding moon-men, and a steamship called the S.S. Méliès: a most loving tribute to the man and his work.

Le Voyage Dans La Lune is often referred to as the first science fiction film. This is not true, of course: film-makers including Méliès had certainly dabbled with similar themes prior to 1902; while the film itself is “science fiction” only by its broadest definition, that is, in that it deals with space flight and aliens. (It is, in other words, the lineal ancestor not of 2001, but of Star Wars; while 2001 is the offspring of Fritz Lang’s Frau im Mond.)

However, it might be fair to say that Le Voyage Dans La Lune, and Méliès’ equally ambitious follow-up to it, Voyage À Travers L’Impossible, are the emotional progenitors of the science fiction genre. While there is no attempt at scientific accuracy to be found in them (ironic, given Verne and Wells as sources), and not the faintest sense that Méliès believed in the tales he was telling, what they do possess is a most marvellous sense of wonder, an awareness of the universe’s possibilities and an eagerness to embrace them. It is this quality that gives these primitive yet powerful works their enduring ability to delight and entertain; and it is a quality that we associate with the very best of science fiction.

Want a second opinion of Le Voyage Dans La Lune? Visit 1000 Misspent Hours – And Counting.

********************************************************

This review is part of the B-Masters’ examination of silent cinema.

Reblogged this on Mike's Movie & Film Review.

LikeLike

Excellent review and analysis. I don’t think I’ve ever seen anything other than excerpts of this film–I’ll have to track it down. The color looks gorgeous. Have you seen the “Lumiere,” um, film project, where various directors (David Lynch, John Boorman, etc) were given a Lumiere camera and made one-minute films? Interesting what people can do with the technology they have. That’s what’s always been surprising about Melies.

LikeLike

Thank you! The colour version is available online and really worth watching—the restoration of the colour brings out the amazing detail, much of which was lost in the B&W copies.

I actually own Lumière (NTSC video, so I must have acquired it quite some time ago!) – thank you for putting me in mind of it. Proof, I guess, that it’s about the imagination and not the tools!

LikeLike

Before I dropped cable last year, they had a batch of Méliès stuff on Turner Classic Movies, including the color version of this (I’d never seen more than clips of the B&W one; this is one time I was okay with something being colorized) and that Arctic one with the super-awesome ice giant. Truly incredible stuff.

LikeLike

Yeah, funny you should mention the super-awesome ice giant… 😀

LikeLike

Downloaded and watched a few hours ago. While the restoration and color use was terrific, and the film itself superb–I can’t thank you enough for this–the soundtrack by some group called “AIR” was awful. I recommend watching this with something else as a soundtrack. Fats Waller on piano or Steve Roach’s “The Magnificent Void” or even silence.

LikeLike

You’re very welcome!

Silence is usually my preferred option. When you’re going over and over a film as I do, a poor music choice can become a form of torture.

LikeLike

Pingback: Conquest Of The Pole (1912) | and you call yourself a scientist!?