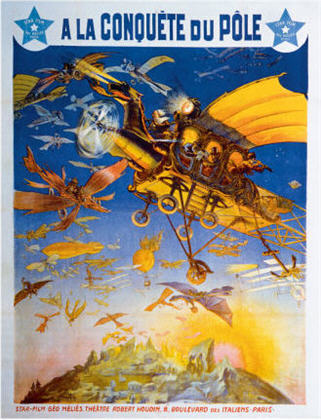

[Original title: À La Conquête Du Pole]

Director: Georges Méliès

Starring: Georges Méliès, Fernande Albany

Screenplay: Georges Méliès, based upon a novel by Jules Verne

Synopsis: At a gathering of the great minds of the world, it is decided to undertake an expedition to the North Pole. Each of the delegates favours his own method of transportation, but all are excited and awed when Professor Maboul (Georges Méliès) reveals that he intends to build and pilot a flying machine. Maboul invites his colleagues to his workshop and shows them a model of his machine, then leads the way to his factory, where construction of the airship is nearing completion. When the flying machine is ready, Maboul and some of the other savants depart, to the acclamation of the gathered crowd. Those using other means of transportation – such as balloon, and automobile – meet a grim fate. Meanwhile, Maboul and his team fly through the heavens, encountering comets, planets and constellations. A lash of Scorpio’s tail almost causes the flying machine to crash. It recovers and reaches the Arctic, but does crash upon landing. Maboul and the others admire their surroundings, then set out to investigate one of the great mysteries of the region: the Giant Of The Ice…

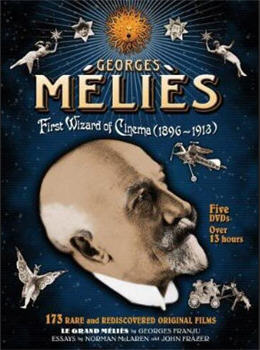

Comments: Circumstances were not kind to Georges Méliès in the decade following the triumph of Le Voyage Dans La Lune. Although he maintained his popularity in the years following the release of his magnum opus, his finances never recovered from the damage sustained at that time. Moreover, the world of cinema was changing. No longer considered a mere novelty, film was becoming a serious business, with companies like Gaumont and Pathé coming to be recognised as a force to be reckoned with not only in France, but all over the world. A one-man operation like that of Méliès – who did nearly everything himself, and oversaw everything else – was simply no longer practical in a market crying out for ever more rapid methods of film production.

Méliès’ life was further complicated by the operations of his brother Gaston, who had remained in America following the debacle of Le Voyage Dans La Lune, and had for some time enjoyed some success as a maker of westerns. However, Gaston’s ambitions began to outstrip his budgets; and the situation worsened when, instead of retrenching, he tried to retrieve his fortunes by undertaking still more extravagant projects involving, for example, location shooting in the South Pacific.

Another crippling blow fell in 1909. By this time, film was sufficiently big business for the various international factions to agree to the need for an accord. At the resulting Congrès International des Editeurs de Films, held in Paris that year – in which Méliès actually played a leading role – it was agreed among other things (like the general adoption of 35 mm film stock) that in the future the practice of selling completed films would be stopped, and a system of renting adopted instead, with the production companies retaining the rights to their films. This was something that Méliès never adjusted to – the sad irony being that had he rented his films rather than sold them, his finances would have been infinitely stronger. In 1911, no longer able to deal with a changing world, Méliès reluctantly entered into an agreement with Pathé, a partnership that instead of helping, finally had the result of hastening the end of his career.

The cumulative effect of all these blows upon Georges Méliès can be judged by his ever-diminishing creative output. At the height of his success, Méliès was making something in the vicinity of eighty films a year; in 1912, he made only five. As things turned out, however, among those five is one of his most enduringly popular, another that contributes to the contemporary vision of Méliès as one of the fathers of the genre film. À La Conquête Du Pôle is for the most part a science fiction-adventure story very much in the mould of Le Voyage Dans La Lune – frankly, rather too much in the mould of Le Voyage Dans La Lune – but at its climax it produces something original, something that moves it into the realm of the horror movie, and would endear the film to generations to come: A Honking Big Monster.

But first things first!

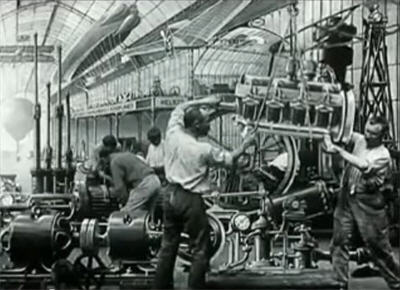

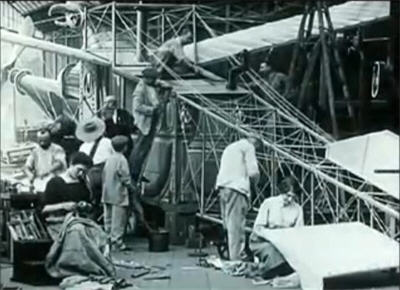

À La Conquête Du Pôle, which is very loosely based upon Jules Verne’s The Adventures Of Captain Hatteras, as well as on a now-lost film by R.W. Paul, Voyage Of The Arctic, opens with a congress of “savants”, who decide to undertake an expedition to the North Pole. The leader of the group, a bearded chap called Professor Maboul (played as usual by Méliès himself), invites some of the others into his workshop, to show to them his model of the “flying machine” with which he intends to attempt the assault upon the pole.

A curious mixture, those other savants: we have a Spaniard in a sombrero and a Mexican in full bandido regalia; there’s a fan-waving, be-robed Japanese man, and a fur-hatted and bearded Russian, and so on. There is a slightly uncomfortable vibe to this blunt stereotyping, though it is offset by a sense of comradeship and bonhomie amongst the savants. (The problem, I suppose, is that the nationality of the other adventurers is ultimately irrelevant.) Maboul demonstrates the model of his flying machine, then conducts the others into his factory, where the real machine is under construction. Enthused, the others dedicate themselves to the expedition.

In the next sequence, we get the distinct impression that Georges Méliès’ always macabre sense of humour had, over the intervening years, either naturally or due to his increasingly difficult circumstances, crossed the line into the realm of outright cruelty. The savants are not the only ones presented via crude stereotyping: the early stages of the film are punctuated by an unfunny running joke involving a group of suffragettes.

While Méliès would have enjoyed the tribute paid to him in the “Tonight, Tonight” music video, there was one aspect of that to which he probably would have objected: the fact that Billy Corgan & Co. have a woman as an equal participant in the adventure, eagerly boarding the flying machine, duelling with Selenites, riding a rocket and swimming in the ocean. Women did not fare quite so well in Méliès’ own films, where for the most part they were cast as sex objects, as victims, or as the targets of mockery.

Such is the case here. The leader of the suffragettes turns up again as the various expeditionary groups prepare to set out. She has brought a flying machine of her own, something like a helicopter built out of balloons, but is denied permission to participate in the expedition. She then tries to force her way onto Professor Maboul’s flying machine, but is forcibly ejected.

Only a few of the savants win a place in Maboul’s flying machine, and the others seek alternative methods of transport. One group decides that they will fly to the pole (!!), while another chooses to travel by balloon. As the balloon begins to ascend, the leader of the suffragettes rushes up and grabs onto the basket. The man on board shakes her loose (!!!), and she tumbles through the air – fussing with her hair on the way down – to end up impaled upon a church steeple…between the legs (!!!!). This being a Méliès film, she then explodes.

Mind you, most of this film’s male characters don’t fare much better. In fact, in the process of detaching the suffragette, the balloonists lose much of their ballast. The balloon goes soaring into the stratosphere where, yes, it explodes.

Meanwhile, those attempting to approach the pole by automobile (models that look charmingly forward to the special effects of Eiji Tsuburaya, and the work of Gerry and Sylvia Anderson), succeed only in driving obliviously onto a rickety wooden bridge over a gorge, which collapses beneath their weight. The rest of the party, lemming-like, plunges over the cliff in the wake of their leaders.

So much for “savants”.

A cutaway shows us that Professor Maboul is not the only one who has undertaken the expedition by air: a whole squad of flying machines, of a myriad of designs, is in the air. However, only the Professor’s machine has the power to soar through the heavens, where it has the usual Mélièsian celestial encounters, and causes the usual amount of Mélièsian damage.

The machine flies straight into Saturn, here a construct with a grotesquely laughing face, and Saturn, yup, explodes. Though badly shaken up, Maboul and the others travel on, flying past various constellations of the female-chorine variety, and others representing the signs of the zodiac. (“Libra: today you will encounter a peculiar Frenchman in a flying deathtrap…”)

This interlude, however, is almost the end of them, as Scorpio strikes at the travellers with the stinger in its tale. The flying machine spins wildly, but Maboul manages to bring it under control. Not even a violent storm can stop him: he and his crew alone, out of all of those who set out, reach the North Pole.

Maboul brings his flying machine in for a landing on the ice, but in the process the machine itself crumples and crashes, and large chunks are torn out of the hitherto pristine Arctic landscape.

As always, Homo sapiens: wrecking the joint wherever he goes.

The adventurers themselves are uninjured, and they begin to explore their surroundings. Here again we get some of Méliès’ glorious constructed landscapes, as an Arctic of dramatic ice formations, soaring pinnacles and dangerous crevasses. After congratulating each other, the adventurers set out to investigate “le mystère du Pôle”…

How many of us, during the years prior to the ready availability of Méliès’ work (we are so spoiled these days!), were tantalised and tormented by stills from the following sequence, reproduced in various books? Maboul and the others discover a strange opening in the ice, and even as they begin to examine it, something stirs within: le géant des neiges, the giant of the ice.

This marvellously imaginative creation is nothing less than a full-sized marionette, towering over the human actors as it is, self-evidently, manipulated by out-of-shot stage-hands. There is a delightfully contradictory aspect to the realisation of our giant: in truth, the operation of the marionette is not particularly well done; his eyelids and his arms are continually out of synch.

However, the result of this is to bestow upon the giant a real personality: with his bizarrely uncoordinated movements, he finally comes across like the drunken, disreputable uncle of one of the Sesame Street gang. (I particularly like the moment when he seems to be winking at the camera while giving us all the big thumbs-up.)

The explorers, understandably terrified, at first run for cover as the giant slowly emerges from his icy retreat. Then they decide to attack him, first by shooting at him, which has no effect, and then by pelting him with snowballs. The giant’s reaction to this is one that is censored from many of the surviving prints of À La Conquête Du Pôle: he catches up two of the adventurers in his hands, and eats one of them alive, with much appreciative champing of his jaws.

(In fact, in a bit equally hilarious and gruesome, the monster grabs two of the explorers at once and hesitates between them. Evidently the fervent prayers of the Spaniard were heard, as the monster devours his companion instead!)

In response, the remaining adventurers step up the attack, producing a cannon from the wreck of the flying machine (don’t leave home on your Arctic expedition without one) and firing it at the giant. This has the result of making the giant spit out the devoured adventurer, who proves to be alive and in one piece (which seems rather unlikely, all things considered); and then the giant sinks back into the ice.

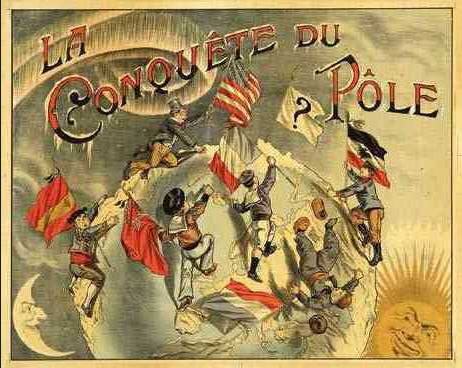

Next the adventurers achieve their supreme triumph by reaching the North Pole – represented by a literal pole, of course. After shaking each others’ hands vigorously, they claim the pole by each planting a flag representing their own nation.

The men then get a dramatic illustration of the fact that this is not merely the North Pole, but the North Magnetic Pole: venturing too close, they are irresistibly drawn to the pole and stick to it, struggling helplessly as it rotates. This rather comic episode then turns to tragedy as the pole collapses under the combined weight of the explorers, and it and they sink into icy waters.

All seems lost for the adventurers until, suddenly, a second flying ship appears (and just who may be piloting that, we never do learn). As the ship hovers over the crevice, it lowers a rope ladder, which Professor Maboul scales. It seems at this point that only the Professor will be saved, but as the flying ship pulls away we do get the briefest glimpse of a strange object being extracted by rope from the crevice. It is the other men, trussed up in an exceedingly uncomfortable-looking bundle. The ship flies off with them still dangling from a rope.

The last scene gives us Professor Maboul and the other explorers being lauded by their peers of le Club Aéronautique.

À La Conquête Du Pôle is a charming work in its own right, but it also highlights the basis of much of the criticism that in certain quarters has been levelled at Georges Méliès. Put bluntly, the film is just Le Voyage Dans La Lune all over again, something quite painfully apparent during the first half, which reproduces the meeting, the construction of the means of transport, and the departure scenes of the earlier film. The subsequent flying scenes are exactly the same, with the explorers encountering the same heavenly bodies as their predecessors did on the way to the moon, right down to Saturn and the star-women, and those two young women holding up a star. The arctic landscapes, although beautiful creations, are also too similar to the moonscapes of a decade earlier.

Of course, all of this is much more obvious today, when we are able to sit and watch examples of Méliès’ work back-to-back, than it would have been at the time of their release, when film was a most ephemeral entity, to be watched once and often discarded. It is quite possible that audiences of 1912 welcomed a reappearance from such old friends as the celestial women – assuming that the film didn’t play to a new audience altogether.

However, a viewing of this film makes it hard to argue against those critics who claim that Georges Méliès never grew as an artist. Other than the single concession of intertitles instead of a narrator, there is little here to tell us that À La Conquête Du Pôle was made in 1912 rather than 1902. The bag of tricks – painted backdrops, superimpositions, explosions, jump-cuts – has not altered one iota over the preceding decade.

The plain fact is that Méliès never had any real interest in cinema as cinema; his aim was, rather, to use cinema as a means of preserving the traditions of the theatre, to which he was passionately devoted. It is rather unjust, therefore, to criticise the man for not doing what he never tried to do, or for not being what he never intended to be. At the same time, it is easily understood how contemporary film-making could overtake and then abandon Méliès.

By 1912 the cinema was on a very different evolutionary path. A real language of film had been developed, thanks to pioneers such as Edwin S. Porter. All over the world, production was exploding, resulting in longer, more carefully scripted and executed narratives; while actors – “stars” – and directors were beginning to become publically known and acclaimed. Within two years of the release of À La Conquête Du Pôle, the Italian cinema, already developing a tradition of historical and biblical productions, would produce the three-hour epic, Cabiria; in Germany, film-makers like Robert Weine and Paul Wegener and the American-born Arthur Robison were winning fame with their tales of the Unheimliche; while in America, David Wark Griffith was honing the skills that before long see him hailed as the leading director in the world. Beside all this, the works of Georges Méliès begin to seem quaint to the point of absurdity.

The partnership with Pathé, entered into so reluctantly, brought Méliès little but further grief; he made his final film in 1913. With the outbreak of war, Méliès was forced to close his beloved Theatre Robert-Houdin, and subsequently earned a living by converting his film studio into a small theatre and running a repertory company comprised largely of family members. This lasted until the early twenties when Pathé, from whom Méliès had parted most acrimoniously, tried to recoup some of its own debts by forcing the sale of Méliès’ remaining assets. At the same time, the Theatre Robert-Houdin was ordered to be demolished to make way for a road-building project.

In the face of this final, overwhelming blow, Georges Méliès would wreak a terrible revenge upon posterity – and, unknowingly or uncaringly, upon himself. Méliès was compelled to remove his remaining possessions from the theatre prior to its demolition. Amongst them were crates containing the negatives of his films. In his anger and misery, Georges Méliès ordered those crates and their contents destroyed…

The crowning irony of all this is that the film pirates against whom Méliès had fought so bitterly for so many years, and who had cost him so enormous a portion of the profits he should have earned, are the main reason why today we still have as many of Méliès’ films as we do. It is, granted, only a third of the total – catalogues preserved from the time indicate that Méliès made something like 560 films, of which less than 200 survive – but considering that we might have, in that moment of madness, have lost all of Méliès’ work, we can only be grateful for this partial mercy.

Over the years following his retirement from film-making, Georges Méliès was periodically “rediscovered” – literally, in the first instance, when in the late twenties he was recognised by a film critic while at work in the small shop that was by then his main support. Some of his films were found and screened in 1929, to a rapturous reception from the public that at long last provided a balm for Méliès’ lingering hurt. Méliès’ last years were spent peacefully in a retirement home for veterans of the film industry. He died in 1938. In 1952, Méliès’ widow, Jehanne d’Alcy – she of the heavens, and of that shocking near-nude bath scene in Après Le Bal – and their son, André, were heavily involved in the production of Le Grand Méliès, a telling of the man’s life and film-making career directed by Georges Franju; Andre Méliès was allowed to star as his father. At long last, Georges Méliès received his full due.

For something too often dismissed as “novelties” – as opposed to “real” films – the productions of Georges Méliès would prove to have a huge impact upon generations of film-makers; Charles Chaplin, René Clair, Luis Bunuel and – I take it all back: this is the crowning irony – D.W. Griffith are just a few of the directors to claim Méliès as a major influence; while from the 1920s onwards, those taking up employment in a whole new film-making realm, the special effects artists, would only too obviously look back to Méliès for inspiration.

Those of us who love cinema fantastique are incalculably in his debt: horror, fantasy, and science fiction films; monsters and demons; aliens and lost worlds; inventions and expeditions; mad scientists and their bizarre experiments; evil doctors and their disregard for ethics…all of these cinematic standards, and many, many more, have their roots in the imagination of Georges Méliès, and the alternatively bizarre, unnerving and charming celluloid fever-dreams to which it gave birth.

*****************************************************************

This review is part of the B-Masters’ celebration of silent cinema.

Interestingly, given how non-innovative this is in most respects, it’s using some very up-to-date elements; 1912 is still very much in the pioneering era of heavier-than-air flight (first west-to-east flight across the USA happened that year). (See also HP Lovecraft and the discovery of Pluto.) It’s interesting to contrast Jules Verne, who seems to have got the science fiction bug after a balloon flight.

“Exploding Suffragette” would be a good band name, though.

LikeLike

YAY super-awesome ice giant! Everyone should see this; the awesome just can’t be conveyed via stills.

LikeLike

“Super-Awesome Ice Giant” would also be a good band name. (It sounds rather like the literal translation of something Japanese.)

LikeLike

Oh wow, you’re right, that is a band name waiting to happen!

It sounds like some sort of tokusatsu show. “Super-Awesome Ice Giant Daifrieza! Coming this fall from Tsubaraya Studios!” I’m rather ashamed I didn’t make that connection immediately.

LikeLike

Cool review. The ice giant stuff is quite good, all things considered.

LikeLike

The Rev is right, it’s even better in motion.

LikeLike