“She fears something more than mere mental derangement…”

Director: D. W. Griffith

Starring: Henry B. Walthall, Spottiswoode Aitken, Blanche Sweet, George Siegmann, Ralph Lewis, Mae Marsh, Robert Harron

Screenplay: D.W. Griffith, based upon the works of Edgar Allan Poe

Synopsis: A boy left orphaned as a baby is adopted by his uncle (Spottiswoode Aitken), who swears to devote his life to the child’s care. At first a careful and affectionate guardian, the Uncle becomes domineering and even tyrannical as the Nephew (Henry B. Walthall) grows to manhood, sometimes forbidding the young man even to leave the house. Inspired by the works of Edgar Allan Poe, the Nephew decides upon a literary career. He also falls in love with a local girl, whom he nicknames “Annabel” (Blanche Sweet). However, certain of his Uncle’s disapproval, the Nephew keeps his engagement to his Sweetheart a secret. Rejecting his Uncle’s plea to stay home, the Nephew meets and walks with his Sweetheart; the Uncle sees them together, and later accuses his Nephew of ingratitude, throwing all of his sacrifices in the young man’s face. Recognising his emotional debt to his Uncle, as well as his financial dependency upon him, the Nephew gloomily agrees to do as he is bid. Not understanding the extent of the Uncle’s possessiveness, the Sweetheart calls at his house to introduce herself, and to invite both men to accompany her to a garden party. However, the Uncle reacts with fury, and insults the girl to her face. She flees the house, humiliated. The Nephew, outraged by his Uncle’s conduct, defies his commands to stay at home and goes after his Sweetheart. The two do attend the garden party, where their unhappiness is compounded by the sight of other, happy couples around them. They decide that, in the face of the Uncle’s obduracy, the only thing they can do is agree to part. The Uncle follows his Nephew to the party, where the sight of happy couples and young families makes him recognise both his own loneliness and his unreasonableness. At home again, he prays fervently for guidance. Meanwhile, bereft of his love, the Nephew sits sadly alone, and suddenly becomes aware of scenes of natural violence around him: a spider devours a fly, while upon the ground, ants swarm and battle. Slowly, an evil thought takes possession of the young man’s mind…

Comments: The early history of cinema may seem to the uninitiated a case of the cart before the horse. “Cinema”, as we know it, sprang not from a vision of a new form of entertainment and art, but was the purely practical outcome of technological developments, as various parties around the world – including the Lumière brothers in France, and Thomas Edison in America – used short films as a way of advertising their new camera equipment. The American Mutoscope and Biograph Company – later simply called Biograph – was co-founded by William Kennedy Dickson, who had worked as Edison’s assistant and played a significant role in the development of the Edison “Kinetoscope”. At Biograph, Dickson not only developed a new camera that rivalled Edison’s, but also invented a distinctly superior projection system.

Possibly as a result of this, by the early 1900s Dickson’s company had shifted its focus to the creation of what it called “actualities”, short films of two or three minutes footage that, like the pioneering works of the Lumières, consisted of scenes of real life. However, rival companies both in America and in Europe were having even greater success releasing short narratives; and from 1903 onwards, Biograph, too, would follow this path. In pursuit of this end, the company created a new studio, the first in the world to be entirely enclosed and operated under artificial lighting. By 1908, Biograph had given up on the “actualities” on which its initial cinema success was founded, to concentrate upon the production of one-reel fiction films. During the same year, needing to bolster its artistic ranks, the company offered a job to an actor then in the employ of the Edison Studios, a Kentuckian by the name of David Llewelyn Wark Griffith.

D.W. Griffith’s first artistic ambitions had been literary in nature. While trying to establish himself as a playwright, he found employment as a stage actor and spent more than a decade touring America with various stock companies. It was not until 1907 that Griffith finally succeeded in having a play produced, and then it was a comprehensive flop. Still dreaming of finding fame as a writer, Griffith turned to the burgeoning motion picture industry, which was hungry for new talent, only for history to repeat itself. The script that Griffith submitted to the Edison Studios, an adaptation of Tosca, was rejected, but head producer Edwin S. Porter hired him as an actor. Griffith made has screen debut in Rescued From An Eagle’s Nest, which was directed by J. Searle Dawley, who would later write and direct the screen’s oldest surviving version of Frankenstein; while Griffith’s co-star, also in his first acting role, was a man with whom the future director would forge a significant artistic partnership, Henry B. Walthall.

After only one more film for Edison, Griffith moved to Biograph, from which time onwards he barely had time to breathe. As a part of leading director Wallace McCutcheon’s stock company, Griffith appeared in around two dozen films shot in extremely rapid succession. However, McCutcheon suffered a breakdown during 1908; he was initially replaced by his son, Wallace Jr, but the younger McCutcheon’s talents were comedic rather than dramatic. Needing to find a new dramatic director in a hurry, Biograph’s general manager, Harry Marvin, after consulting with his brother Arthur, one of the company’s leading cameramen, decided to offer the job to D.W. Griffith.

It would be an understatement to say that Griffith repaid Biograph’s faith: still appearing occasionally as an actor and, since at the time most directors also crafted their own scenarios, in some measure finally achieving his ambition of working as a professional writer, before the end of the year Griffith would helm almost fifty one-reelers, while during 1909 he would churn out no less than one hundred and forty-eight short films—one every two to three days. (One of these would be the director’s first attempt at paying tribute to one of his personal heroes, a seven-minute biopic entitled Edgar Allen Poe.) However, as Griffith’s importance to Biograph increased, his output decreased – relatively speaking, at any event: in 1910 he made only ninety-six films, and in 1911, only seventy-six.

Permitted to take longer to make his films, and to extend their running-times to between two and four reels, Griffith began to experiment with the form of his creations. Short as had been his time at Edison, Griffith had taken to heart what he had seen there, in particularly Edwin S. Porter’s pioneering use of such techniques as cross-cutting and the use of close-ups. Defying the popular belief that cinema audiences were incapable of understanding a non-linear narrative, Griffith’s approach to story-telling increasingly involved the use of parallel plots to increase suspense, with flashbacks and dream sequences employed to convey his characters’ state of mind. In close collaboration with his cameraman, Billy Bitzer, Griffith also began to trial new forms of camera-placement and lighting, as well as working closely with his actors to develop a more natural form of screen acting, divorced from the stage techniques that still dominated early film—and in many cases would continue to do so for many years to come.

The next turning point in D.W. Griffith’s career came in 1913, when the director began lobbying for the chance to make what we would now call a feature-film: an extended narrative that gave the film-maker an opportunity to delve far more deeply and richly into the telling of a story. Curiously, most of the major American companies of the time were hesitant to tackle this new form of motion picture, evidently due to the belief that audiences did not want longer films; increased production costs were also a concern. This left the door open for various independent producers and distributors, as well as some of the smaller companies, to make strides in the development of the new format, which the rest of the international film-making community had already embraced.

(The Australian production The Story Of The Kelly Gang, released in 1906, is generally credited as the world’s first feature-film. Sadly, only seventeen of its original sixty minutes now survive.)

The Biograph executives, like most of their fellows, stood firm in opposition to the idea of feature-film production, so D.W. Griffith went behind their backs. Already in the habit of travelling to California in order to exploit the light and the settings for his outdoor films – Griffith was the first to shoot in a little village called “Hollywood” – the director began work on his first feature-length production well out of his employers’ view. The result was Judith Of Bethulia. The film was well-received by the critics, but Biograph saw only the bottom line: it had cost the alarming sum of $36,000.

As a result of the ensuing stand-off between Griffith and his employers, which saw Judith Of Bethulia cut down to what its producers considered an “acceptable” running-time for re-release, the director not only walked out of Biograph but took with him Billy Bitzer and the stock company of actors he had spent five years building: Lionel Barrymore, Donald Crisp, Harry Carey, Henry B. Walthall, Blanche Sweet, Mae Marsh and the Gish sisters, among others. Griffith subsequently entered into partnership with Harry E. Aitken, whose Majestic Pictures was a part of the Mutual Film Corporation, a conglomeration of independent producers and distributors who had banded together to fight against the monopoly of the Motion Picture Patents Company, otherwise known as the Edison Trust. Ironically, most of the success of this collaboration was due to its shared enthusiasm for feature-length films.

Griffith’s deal with Harry Aitken saw him take a substantial pay-cut, as well as putting him in the position of having to prove his worth – and profitability – to Aitken’s numerous business partners by turning out a number of standard melodramas; but it also allowed him to make feature films, and promised him the opportunity to produce two independent films of his own choosing per year. Although his thoughts were already running on the ambitious production that would be his first independent film, a version of Thomas F. Dixon’s novel, The Clansman, Griffith was mindful of his new responsibilities and knuckled down to the job at hand.

Across the remainder of 1914, the director made four films for his new employers. Three of these Griffith would later dismiss as “potboilers”; the fourth was The Avenging Conscience, a loose adaptation of the works of Edgar Allan Poe that has some claim to be considered the first serious American horror movie.

These days, of course, the expression “horror movie” sets up certain expectations. Such was far from the case in 1914, when indeed the expression “horror movie” was yet to be coined by the disapproving critics. While the Europeans, the Germans in particular, embraced the macabre and the supernatural from the very dawn of their cinema, in America it was far otherwise, not least because in parallel with the development of film itself came the development of factions determined to blame many of society’s ills upon it. In time the huge popularity of cinema allowed the studios to pay less heed to the finger-waggers – not that the waggers have ever gone away entirely – but at the beginning, when authorities could and would shut down cinemas and nickelodeons for the most minor of perceived transgressions, film-makers were under constant pressure to tell stories that were “moral” and “uplifting”. Horror for its own sake was quite out of the question. Those few directors who did wish to dabble in darker material often turned to literary sources, excusing their transgressions by referencing the “celebrated classic” and thus deflecting any blame from themselves and onto the author.

The Avenging Conscience does indeed have a dark literary source, but unlike many of its brethren there is no sense in this film that D.W. Griffith was looking for a scapegoat. On the contrary, it is clear that, as was the case with Edgar Allen Poe, Griffith intended his work to be a tribute to someone he admired. Amusingly, however, the finished product plays very much like many horror movies of a later era, that seek to exculpate themselves by blaming societal violence and psychoses on the watching of other horror movies. The difference here is that Griffith doesn’t seem to have noticed how strongly he was implying that one possible outcome of too much Poe might be to turn a nice, normal young man into a killer.

It is the middle section of The Avenging Conscience that wins the film its classification as a horror movie, where we find one of the earliest examples of cinematic technique being used to convey a complex psychology. However, contemporary viewers should perhaps be warned that this justly famous sequence is bookended by a mixture of heavy-handed sentimentality and failed comedy—unfortunately, two of the more common Griffith failings.

There is a reasonable efficiency about the film’s early scenes, wherein the orphaned baby is adopted and raised by his uncle, with the two sharing a relationship of mutual affection; and the first scene between the Uncle and the Nephew wherein the latter is an adult conveys the shift in that relationship with commendable subtlety. We see via a not-quite exchange of glances the Uncle’s growing fear that he is beginning to lose his hold on his Nephew, who in turn feels the first stirrings of resentment, as he chafes against his prescribed and dependent existence. The catalyst of the Nephew’s change in attitude is his secret love affair with his Sweetheart; the alteration in his expression as he glances from a note written by his fiancée to his Uncle tells us all we need to know about why the romance is being kept a secret.

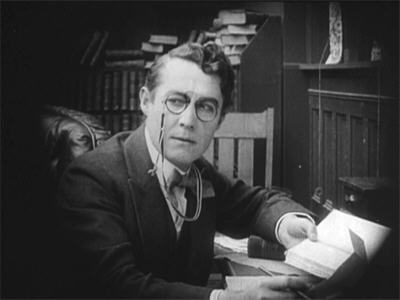

The Nephew is played by Henry B. Walthall, one of Griffith’s favourite actors; and his contribution here is something of a mixed blessing. Walthall was thirty-six when he appeared in The Avenging Conscience, and there is no getting away from the fact that he was much too old for the part he was playing; the Nephew by rights should have been only just out of adolescence. The problem is at once exacerbated and excused by the fact that Griffith spends much of this film playing with the art of the close-up. While Walthall’s real age is obvious, in The Avenging Conscience we see the strides that Griffith had made since he began experimenting in his short films with the more subtle methods of conveying emotion. Once the idea of murder has entered the Nephew’s mind, and his worse and better natures begin struggling with each other, Henry Walthall offers up a fine piece of silent film acting, in the range and the shadings of expression that flit across the Nephew’s face. In conjunction with Griffith’s repeated use of the close-up, this sequence illustrates a critical stage in the evolution of film-making. Later on, however, Griffith and Walthall fall back upon early cinema’s old, unsubtle ways, with the Nephew’s mental and emotional suffering conveyed via the usual stand-bys of face-pulling, hair-clutching and arm-waving.

The use of designations rather than names in The Avenging Conscience indicates that Griffith saw his characters more as allegorical constructs than as real people. Blanche Sweet suffers particularly from this approach. We are introduced to the Sweetheart in a series of scenes that are all too typically Griffith, wherein Miss Sweet is compelled to adopt all the fluttery mannerisms usually associated with the director’s girl-women. Even at their best executed these sorts of characterisations are trying for those of us who don’t happen to share Griffith’s particular taste in heroines, but without any unkindness intended, the fact is that Blanche Sweet was not nearly ethereal enough to get away with kind of behaviour, and it is hard not to feel a little embarrassed for her here. This kind of role was something of an anomaly for Sweet, who usually played a much more grounded, practical type of young woman. The Sweetheart does show a certain independence when she tries to take the conduct of her relationship with the Nephew into her own hands, but after this backfires she is reduced to resignation, self-sacrifice and tears.

Our first intimation of the dangerously possessive turn that the Uncle’s affection for his Nephew has taken comes when he tries to stop the young man from even leaving the house; likewise, the impatient way that the Nephew shrugs off his guardian bodes very ill for the future. The Nephew is going out to meet his Sweetheart, as the Uncle learns to his dismay when he sees the two together, walking by the river. It is the next day, when the Nephew prepares for the garden party, that matters reach a crisis. The Uncle again tries to prevent the Nephew from leaving, throwing in his face his own “sacrifices” and demanding in return “a few years of gratitude”. Reluctantly, the Nephew gives in to his Uncle’s demands, and sits back down at his desk.

However, in her note the Sweetheart intimated that she might call for the Nephew, and at this very ill-timed moment, she does so. Anticipating no evil, she introduces herself to the Uncle, inviting him to the garden party. The Uncle’s response is a crude insult. Shocked and mortified, the girl withdraws. In an excusable rage, the Nephew shakes off the clutching hands of his Uncle and goes after her.

What is interesting in all this, certainly in terms of what follows, is how justified the Nephew’s resentment and anger towards his Uncle seems. The Uncle’s insistence upon his own sacrifices and his demands for gratitude are as unwise as they are ungenerous; we have seen enough to know that everything he did for the boy was done voluntarily, and we will soon learn that he has sufficient resources put away to constitute a desirable “inheritance”. There is certainly nothing unreasonable in the young man’s desire for a life of his own, however much the Uncle’s irrational fears insist to him that to give the Nephew freedom is tantamount to preparing for his own abandonment.

From our perspective, far from being ungrateful, the Nephew seems absurdly compliant…except, of course, for the little matter of the finances; it comes as no surprise to learn that the Uncle has made no separate provision for the young man, but compels his obedience by keeping him dependent. At one point the Uncle physically drags the Nephew towards his desk and points at a journal, presumably the household accounts. It is possible that there has been some extravagance on the Nephew’s part, but we are given no concrete proof of this; and indeed, from we see it is hard to know when or how the Nephew could have had the chance to contract a debt. When we learn that the “career” that the young man is intended for is literary in nature, it is hard not to think that its main attraction for the Uncle is that it doesn’t involve the Nephew leaving the house!

At the garden party, the Nephew and his Sweetheart walk disconsolately amongst all the more fortunate, happy couples. They discuss their situation and finally agree that in view of the Nephew’s dependence, they have no choice but to part. The Sweetheart goes home to cry, while the Nephew slumps miserably onto a bench. Meanwhile, the Uncle has followed the two to the party, where the sight of all the youthful cheerfulness around him begins to have an effect: at length, he recognises his own unfairness, in preventing his Nephew from finding happiness in his own way. Unfortunately, however, the Nephew’s own thoughts have taken a very dark turn. He witnesses death and savagery all about himself, as he gazes into the insect world, until he begins to believe, Nature one long series of murder. This, the intertitle tells us, represents, The birth of the evil thought. As a result, the Nephew conceives, The plan of a fevered brain…

Later, as the Uncle dozes in his chair, the Nephew produces a gun, pointing it in a way almost playful, as if he is still trying to convince himself that he doesn’t really mean it. Then, sobering, he draws near his sleeping guardian and brings the muzzle of the handgun close to his temple…only to pause as voices outside suggest that a shot might be heard. The Nephew puts down the gun and then, as the Uncle begins to wake, picks up a curved walking stick instead. This, too, he discards, instead approaching his Uncle and bluntly demanding money, so that he may go away.

However chastened the Uncle may have felt before he had his nap, those kinder impulses evaporate in the face of this ultimatum; he flatly refuses. The Nephew becomes more importunate as his anger rises again; and as the Uncle persists in his rejection of the demands, the Nephew seizes him by the throat…

And then he disposes of the body by bricking it up within the wall of the fireplace, conveniently undergoing renovation.

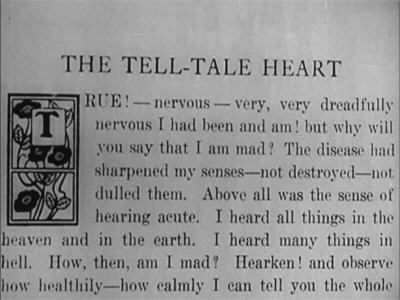

Although not a true adaptation of any one of Edgar Allan Poe’s works, The Avenging Conscience contains any number of allusions to The Tell-Tale Heart. The Nephew is seen at the beginning reading that very story; a copy of the famous daguerreotype of Poe forms the book’s frontispiece; we are given a close-up of the text. After the murder, the Nephew’s state of mind is conveyed by an intertitle that re-phrases a portion of the tale’s famous opening: I saw all the things in the heaven and in the earth. I saw many things in hell; while later, when he is overcome with remorse, another title observes, Conscience overburdened the telltale heart. The Nephew is also driven to near madness by repetitive sounds that to his tortured nerves are, Like the beating of the dead man’s heart. However, in place of the “pale blue eye” that becomes the focus of the narrator’s obsession in the story, Griffith gives the Uncle an eye-patch, which both places him amongst Griffith’s pantheon of older characters who are somehow “damaged”, and in a certain sense shifts the moral culpability for the crime.

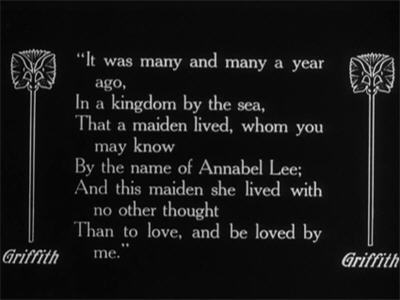

There are many other references here, direct and indirect, to Poe’s writings. The Sweetheart is never named in the text, but the Nephew nicknames her “Annabel”; and the state of their mutual passion, first happy and then miserably frustrated, is communicated by means of extensive quotations from the poems Annabel Lee and To One In Paradise; this use of poetry about the death of a loved one to describe an extant love affair is creepy in a way that Poe probably would have approved of.

At length, the Nephew begins to suffer horrible visions, which he describes via a quotation from The Bells: They are neither man nor woman; they are neither brute nor human; they are ghouls! And of course, the walling up of the Uncle’s body recalls both The Cask Of Amontillado and The Black Cat.

(There is in fact a cat in the household, but we never see it again after an early, suggestive glimpse.)

However, The Avenging Conscience owes its deepest debt to Poe in the way that it tries to put the viewer within the mindset of its story’s protagonist. In this respect, this is a remarkably ambitious work, with Griffith employing all sorts of cinematic tricks to enrich the psychological aspects of his tale. In the lead-up to the murder, as the Nephew stares at the desk that his Uncle usually occupies, there is an almost subliminal flashback to the moment when the Nephew witnessed the devouring of a fly by a spider. When he hesitates after drawing his gun, the Nephew thinks of his Sweetheart, who we see gazing mournfully into the night sky from her bedroom window; this vision of the girl steels the Nephew’s resolve.

Once the deed is done and successfully concealed, the Nephew is visibly pleased with his own cleverness, at least until his Sweetheart visits. (She turns up with amusing promptitude upon hearing that the Nephew has come into his inheritance; hmm, perhaps the Uncle was right about her after all…) The Nephew is still rapturously greeting his “Annabel” when his eyes widen in shock and he stares past her open horror. From the bricked-up fireplace we see emerge the ghost of the Uncle, reaching out with those same clutching hands and pointing an accusing finger before gripping his own throat.

The Sweetheart is disturbingly swift in putting the correct interpretation upon the Nephew’s behaviour – leading to that wonderful intertitle, She fears something more than mere mental derangement; I simply love the use of the word “mere” in that sentence! – and hurriedly leaves the house. Blanche Sweet is excellent in this scene, as the Sweetheart grapples with the dawning of an unspeakable suspicion.

Convincing himself that he has experienced an hallucination simply because of overtiredness, the Nephew retires to bed. He does suffer a momentary qualm as he remembers his Uncle, but shrugs it off and settles down to sleep. But no rest is forthcoming. Instead, the Uncle’s ghost enters the room via the window and looms towards the bed as the Nephew shrinks beneath the covers.

The Nephew, very modern in his views, diagnoses himself with a nervous breakdown and retreats to a sanatorium, from where he returns an unspecified time later, “cured”. He immediately seeks out his Sweetheart, who is willing enough to believe her suspicions unfounded. A smile of relief has barely crossed her face, however, before the Nephew is again staring past her and cowering in terror from something that she cannot see. He abandons her and runs home in a panic, as the voice of his “avenging conscience” engulfs him.

In an agony of remorse, the Nephew begins having repeated visions of Christ, alternately emblazoned in holy light and upon the cross, these being intercut with further visions of Moses on the mount, holding stone tablets emblazoned with the words, Thou shalt not kill.

(What is most startling here is the clarity of these visions, at a time when most film-makers shied away from having an actor “play” Christ. Sadly, but not surprisingly, I am unable to tell you who did so.)

The Nephew writhes upon the floor, simultaneously suffering abject terrors and imploring forgiveness. When the fit passes, he staggers to his feet, exhausted but smiling, and evidently feeling that the worst is over.

But the Nephew’s ordeal is far from over; a threat of a more material nature is closing in upon him. In disposing of his Uncle, the Nephew concocted a plan involving a forged note, which sent the Uncle away to a cottage over a hill on the far side of the local village. Ensuring that the Uncle’s outward journey was marked by eyewitnesses, the Nephew also contrived for his return home to be unseen; thus he simply “disappeared”. However, the subsequent murder was not unseen, but partially observed through an imperfectly shielded window by a passing ne’er-do-well, who promptly resorts to blackmail.

Of all Griffith’s archetypes, this is the most unfortunate: this reprobate is billed only as “the Italian”, and there is a definite sense that we are supposed to find the blackmailing ways of this foreigner more reprehensible than the Nephew’s homicidal behaviour.

Left with little choice, the Nephew promises the Italian a rich reward for his silence, once he comes into his inheritance. The circumstances of the Uncle’s disappearance convince the authorities that he is dead (a little too quickly for comfort, actually), and soon the Nephew is luxuriating in his unaccustomed wealth. However, one person, an old friend of the Uncle’s, is not satisfied; and he introduces another friend, billed as “the Stranger”, to the Nephew, who of course feigns great sadness and puzzlement over his Uncle’s fate. The Stranger looks carefully around the cottage, and is immediately struck by a discordant detail: What a peculiarly shaped fire-place! he observes, giving the Nephew a meaningful smile and withdrawing with the Uncle’s old friend.

As the Nephew begins to suspect, the “Stranger” is indeed a detective, who rapidly becomes convinced of the Nephew’s guilt, and makes arrangements for his capture. Simultaneously, the Nephew’s paranoia begins to grow; he recruits the Italian to keep watch for him, and to warn him should any danger begin to threaten. He also shows the Italian a barn-like retreat, where he keeps arms and ammunition, and where he means to make a stand, if it comes to that.

Soon, these two plot-strands collide. The Nephew has barely recovered from his night of agonies when the Stranger makes his move, inviting himself into the cottage to “ask a few questions”.

To this point, none of the tricks used to illustrate the Nephew’s state of mind have been particularly revolutionary, although they are effective. It is the following sequence, the confrontation between the Nephew and the detective, which makes this film’s reputation, and shows D.W. Griffith’s growing awareness of the narrative possibilities of film technique.

Feigning unconcern, in spite of his slightly dishevelled appearance and obvious distraction of mind, the Nephew invites the detective to sit down. The detective wastes no time, throwing in the Nephew’s face a local rumour that a scream was heard coming from the cottage on the evening of the Uncle’s “disappearance”. The Nephew laughs this off, but his discomfort is obvious. The detective continues to ask questions and take notes, smiling sardonically to himself at the sight of the Nephew’s growing nervousness.

As the Nephew shifts in his chair, he becomes unable to block from his mind an acute awareness of the ticking of a grandfather clock nearby, the remorseless swinging of its pendulum. Noticing, the detective begins to tap his pencil upon the table, watching in satisfaction the effect of this added noise upon the Nephew. Indeed, it becomes to the young man’s frayed sensibilities, Like the beating of the dead man’s heart… Unable to restrain himself, the Nephew puts an impulsive hand over the detective’s, asking him with an unconvincing smile to please stop that tapping. The detective does—for a time.

But that pendulum keeps swinging. And outside, an owl begins to hoot. And the detective starts tapping his pencil again. He also taps his foot. Swing. Hoot. Tap. Tap. Swing. Hoot. Tap. Tap. Swing. Hoot. Tap. Tap. Swing-hoot-tap-tap. Swing-hoot-tap-tap. Swinghoottaptapswinghoottaptap—

And finally the Nephew’s mind collapses; his “telltale heart” can stand no more. He begins to suffer visions of demons and witches; of himself in the embrace of a skeleton; of the Uncle’s death-struggle, his own hands at his guardian’s throat. Under the horrified but grimly satisfied gaze of the detective, the Nephew re-enacts his own part in the murder, before confessing to his crime…

A struggle ensues, and the Nephew breaks away, fleeing to his retreat and making a last desperate stand there, as the detective’s men close in on him. A gun battle follows, which lasts until the Nephew runs out of ammunition. Even then, he does not consider surrender. Instead, he picks up a nearby rope and begins to fashion a noose…

Meanwhile, the sounds of the gun-battle have echoed through the valley. The terrified Sweetheart emerges from her house and learns the worst from a passer-by, hearing of the confession and the stand-off alike. She rushes to the retreat, and reaches it just in time to see the Nephew’s body being cut down by the police officers.

Overwhelmed with horror, the Sweetheart turns and flees. There is a cliff-top nearby, overhanging a rocky shore. The Sweetheart hesitates for no more than a moment, before casting herself from the edge…

And in the wake of all this horror, and violence, and death…

…we fade to the Nephew waking up in his armchair.

Oh, come on. Don’t tell me you’re actually surprised!?

It would be almost another two decades before American film-makers would wholeheartedly embrace the horror movie, and cease to feel a need, artistic or social, to deny the very terrors that they created. In the meantime, film after film would explain away their supernatural events as mere trickery, or dilute their frights with awful comedy. What catches the viewer off-guard about The Avenging Conscience, therefore, is not that it turns out to be – sigh – just a dream, but how far it goes before that in conjuring up its horrors, both in actuality and within its protagonist’s mind. The sense here is that, secure in the knowledge that none of the horrors he was crafting were “real”, Griffith was able to let himself rip. It is also noteworthy that the director allows the accumulating darkness of that middle section of his film to have its full effect upon the viewer, and refrains from undermining it in any way—at least, that is, while it is in progress.

Either side of its focal tale of murder and madness, however, The Avenging Conscience features material likely to strike contemporary viewers as painfully ill-judged. The scenes at the garden party, during which the Nephew and his Sweetheart talk sadly about their situation while surrounded by happy couples, are nicely staged, and beautifully photographed; but then Griffith goes too far by inserting also an allegedly comical sketch involving the courtship of a “maid” and “the grocer’s boy”. It is possible that the director simply wanted to provide an opportunity for an extended cameo by Mae Marsh and Robert Harron, two more of his regular actors, but the tone of this sequence is entirely inappropriate. Short inserts of the “dancing” intended to entertain the guests at the garden party, in which an enrobed nymph contorts before an apparently bored Roman emperor, are also jarring.

But these scenes are nothing compared to the way that Griffith closes his film. When the nephew wakes from his dream, he is at first uncertain as to what is real and what isn’t; he staggers back at the sight of his Uncle, and must reassure himself of the old man’s corporeality by clutching and poking at him, much to the Uncle’s alarm. The Nephew then describes his experience – Oh, such a dream! – after which the two men embrace and share a hearty laugh. (If I were the Uncle, I’m not sure that would have been my reaction.) At this happy moment, the Sweetheart decides that, Uncle or no Uncle, she cannot live without him, and reappears at the cottage. This time she is welcomed instead of rebuffed.

![]()

Now, we can certainly forgive this, but not what happens next. We cut from this to the Nephew and the Sweetheart by the river, where, He quotes from his successful book. The literary critics amongst us might venture to raise their eyebrows in doubt at this, as the scene we see involves a very camp Pan lolling in the woods and playing his pipes, while “sprites” – small children in pantomime attire – cavort around him and various woodland creatures look on. The whole scenario is so horribly twee, it threatens to dissipate entirely the goodwill of the viewer towards this film.

But ultimately, it is not the success or failure of The Avenging Conscience, either in part or overall, that really matters, so much as the magnitude of the film’s ambitions. Indeed, at this stage of Griffith’s career, the director’s imagination seemed to be outstripping his abilities. Thus, the Nephew’s religious agonies are disappointingly literal; while the “ghouls” that he imagines outside his door, which are realised by putting children (probably the same ones from the end of the film) in masks and costumes, are not exactly terrifying.

However, the visualisation of these scenes is less important than their conception, wherein we see Griffith grasping the potentiality of film as a complete story-telling medium. This, of course, is most graphically illustrated during the joint tormenting of the Nephew by the detective and his own conscience. The brilliance of this sequence, with its use of visual trickery and skilful editing to convey repetitive sound, is indisputable; and it represents a critical juncture in the evolution of the cinema, the era when a primitive narrative technique was metamorphosing into a true and sophisticated art form.

Ginger cat = red herring

I’m going to have to watch this one, if only for the sound-expressed-as-images section.

It seems to be on youtube, so that’s helpful.

LikeLike

And that makes the rest worthwhile. There’s some good stuff here but it’s certainly a mixed bag.

LikeLike

so you can tell a story about the most depraved, degenerate, degraded, immoral situations possible, as long as it was just a dream? (and there’s some kind of moral attached)

Or if it’s from the Bible, or classic literature. That gives them plenty of scope.

LikeLike

Scope that they were depressing slow to take advantage of. Darn Americans! 🙂

LikeLike

Pingback: Early signs of madness: A critical review of “The Avenging Conscience” (1914) | Colin Newton's Idols and Realities