“I cannot believe that Godzilla was the only surviving member of its species. If we keep conducting nuclear tests, it is possible that another Godzilla might appear…somewhere in the world…”

Director: Honda Ishirō

Starring: Takarada Akira, Kochi Momoko, Hirata Akihiko, Shimura Takashi, Murakami Fuyuki, Sakai Sachio, Ogawa Toranosuke, Suzuki Toyoaki, Yamamoto Ren, Kodo Kokuten, Tezuka Katsumi, Nakajima Haruo

Screenplay: Honda Ishirō and Murata Takeo, based on a story by Kayama Shigeru

Synopsis: A freighter, the Eiku-maru, is lost when it encounters a strange light in the Pacific Ocean to the south of Japan. A distress call sent before the boat’s sinking brings Lieutenant Ogata Hideto (Takarada Akira) of the Southern Sea Steamship Company to the firm’s head office. The other officials are unable to account for the ship’s loss, but report that another vessel, the Bingo-maru, is in the area and will investigate. But the second ship goes the way of the first… A few survivors of the second steamship are picked up by a fishing boat; they insist that “the ocean just blew up”. The manager of the company (Ogawa Toranosuke) tells the frantic families of the ships’ crews that the survivors are being taken to Ohto Island, and that another vessel, the Kotaka, has been sent to assist. But then word comes that the Kotaka, too, has been lost… On Ohto, the islanders bring ashore a raft, on which they find a local fisherman, Masagi (Yamamoto Ren), who speaks brokenly of a monster before losing consciousness. As time passes, the islanders must cope with the sudden disappearance of fish from the waters surrounding Ohto. An elderly man (Kodo Kokuten) insists that, “Godzilla must have done it”, but the younger people scoff at him. A helicopter carrying a reporter, Hagiwara (Sakai Sachio), lands on Ohto. Masagi tells Hagiwara about the creature in the sea, then reacts angrily to the reporter’s obvious scepticism. The islanders perform an ancient exorcism ceremony, during which the old man explains to Hagiwara that “Godzilla” is the name given to an ancient monster from the sea, who legend states will come ashore to devour humankind; in the past, the islanders held human sacrifices to placate the beast. That night, a violent storm sweeps the island – and with it, a blinding light. Masagi and his mother are killed when their house collapses; Shinkichi (Suzuki Toyoaki), the younger son, escapes. Survivors of the disaster are brought to Tokyo, to testify before a parliamentary committee at the Diet Building. They all agree that the force that swept the island was not an ordinary hurricane. Shinkichi claims that he saw an animal; Hagiwara insists that the houses and the naval helicopter were crushed from above. The famous palaeontologist and marine biologist, Dr Yamane Kyohei (Shimura Takashi), is put in charge of an investigative expedition to the island. In addition to various naval and scientific personnel, and a number of reporters, Yamane is accompanied by his daughter, Emiko (Kochi Momoko), who acts as his assistant, and Lt Ogata. Their departure is watched intently by Dr Serizawa Daisuke (Hirata Akihito), a brilliant but reclusive scientist. On Ohto, the team’s first discovery is areas of strangely localised radioactivity. Yamane examines an enormous depression in the ground, and declares it a footprint. The footprint is also found to be radioactive, and within it lies a trilobite thought extinct for millions of years. An alarm bell sounds. The terrified islanders, as well as the members of the expedition, flee into the hills. Professor Tanabiya (Murakami Fuyuki) finds a stunned Yamane standing on his own: Yamane insists that he saw it, a creature from the Jurassic age. Suddenly, it looms up over a nearby hilltop, a 50-metre high prehistoric monster—Godzilla…

Comments: Although great and influential motion pictures were produced on either side of it, in the history of the science fiction film in America, 1952 is an odd little hiatus of a year. The cinema of 1950 sent humanity to the moon and to Mars in Destination Moon and Rocketship X-M; while 1951 delivered the politically opposed but equally significant allegories, The Thing (From Another World) and The Day The Earth Stood Still—and destroyed the world as mankind then knew it in When Worlds Collide. More, many more, were to follow: It Came From Outer Space, The War Of The Worlds, Them!, The Creature From The Black Lagoon, Forbidden Planet, The Incredible Shrinking Man…

The list goes on and on; yet in the midst of all this, the best that 1952 can offer are interesting but severely flawed efforts like Howard Hawks’ Monkey Business and the bizarre Red Planet Mars, while at its worst—well, Bela Lugosi Meets A Brooklyn Gorilla, anyone?

(The best original science fiction film released in America in 1952 in fact emanated from Britain: Alexander Mackendrick’s The Man In The White Suit.)

Ironically, however, hindsight demonstrates that despite its almost total lack of quality new productions, 1952 was one of the most critical years in the history of cinematic science fiction, not because of any new motion picture, but rather because of the surprising financial success of a nineteen-year-old “jungle picture”. A smash hit upon its first release in April of 1933, King Kong continued over the years to be one of RKO’s most lucrative investments, being re-released to cinemas in 1938, 1942, 1946 and 1952, albeit in increasingly censored form each time.

As events would prove, the 1952 re-release was a watershed of unanticipated but vast importance. For one thing, it was hugely profitable: King Kong earned more money during this run than upon any of its earlier releases, and out-grossed any number of that year’s prestige productions from rival studios. This fact was not lost upon producers Jack Dietz and Hal E. Chester, who in 1950 had come together to form Mutual Pictures of California. One would have to search far and wide to come up with two more unlikely figures to exert such a profound influence upon the development of the science fiction film. Chester was a former child actor who had graduated to production – sort of – spending the forties churning out the Joe Palooka series at Monogram Pictures. It was there that he met Dietz, whose credits at Monogram include some of Bela Lugosi’s most notorious efforts, such as Black Dragons, The Corpse Vanishes and The Ape Man.

The duo did better in partnership, producing the noirish thriller The Underworld Story and the costume drama The Highwayman, before casting interested eyes over the revenue being generated by a certain “jungle picture” and deciding that what American cinema really needed was a brand new monster movie. That was critical decision #1; critical decision #2 came shortly afterwards when Dietz and Chester bought the sales pitch of an aspiring special effects man named Ray Harryhausen, who promised them an unforgettable monster at a bargain-basement price. Made for just over $200,000, The Beast From 20,000 Fathoms sold to Warner Brothers for twice that much and went on become the surprise sleeper hit of the year, pulling in nearly $5 million. Its success would spawn a decade’s-worth of atomic monsters on the rampage, in films varying in quality from the truly great to the simply laughable.

But the influence of these two movies did not stop at America’s shores; and their joint impact upon Japanese cinema can hardly be calculated. In 1953, producer Tanaka Tomoyuki was in deep trouble. A rising star at Toho Studios, Tanaka had travelled to Jakarta to oversee a Japanese-Indonesian production, which had fallen apart when the local backers withdrew their support for the project only weeks before shooting was scheduled to commence. Desperate to come up with a replacement production as quickly as possible, in a flash of inspiration Tomoyuki Tanaka hit upon the idea of a monster movie…but a thoroughly Japanese monster movie. Toho accepted his proposition, and the kaiju eiga was born.

Tanaka’s film went into production with nothing more definite to shape it than an outlined pinched from The Beast From 20,000 Fathoms (which, by the way, had not yet opened in Japan, but with which the producer was certainly familiar, although it remains unclear whether he had managed to see it in another country). Incredible as it now seems, there was a period during which this production teetered on the brink of turning into something dismissible as “just a monster movie”: special effects director Tsuburaya Eiji originally suggested a giant octopus; while scenarioist Kayama Shigeru’s first draft, although it included a “dinosaur-like” monster, had the beast essentially just an oversized animal, driven by hunger.

However, an intense three week development period, during which producer Tanaka, director Honda Ishirō and writers Kayama and Murata Takeo locked themselves away together in a Tokyo hotel, gave birth to something much darker, and far more meaningful: the idea of a monster nothing less than the atomic bomb made flesh.

Several structural blunders mark The Beast From 20,000 Fathoms as the first of its kind, among them its opening-scene glimpse of its monster. Gojira, learning from its predecessors, delays and builds towards this revelation, opening instead with a mysterious light in the sea, and the fiery destruction of the ships that encounter it. While the officials of the Southern Sea Steamship Company in Tokyo struggle to comprehend, let alone deal with, these disasters, the residents of the fishing community of Ohto Island are suffering likewise: a raft bearing a single survivor washes ashore; he speaks brokenly of “a monster”. This disaster is not the only one to afflict the islanders, who face ruin, possibly starvation, from the sudden disappearance of the fishing stocks from the waters surrounding their island. This second catastrophe provokes an elderly man to declare, “Godzilla must have done it”—a statement that draws upon his head the scorn and wrath of the younger generation.

(For the record, the profound honour of first uttering the G-word fell to veteran character actor Kodo Kokuten, whose film credits reached all the way back to the early 1920s, and who at the time was a Toho stock player, appearing in several Kurosawa productions including No Regret For Our Youth and The Idiot.)

By the time Hagiwara the reporter arrives on the island, the islanders’ mood has shifted significantly, to the point where an ancient exorcism ceremony is performed. During this, the old man explains to Hagiwara that Godzilla is the name of “a monster that lives in the sea”, who will “feed on humankind to survive”; in “the old days”, he adds, when the fishing was poor, the islanders used to carry out human sacrifice – of girls, naturally – in order to satisfy the creature and keep it from eating anyone else.

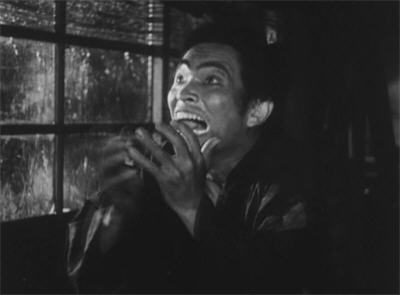

That night, however, a gale-force wind and torrential rain sweep across the island; and as the storm builds, it is accompanied by blinding flashes of light strangely similar to those which preceded the shipping disasters. The storm destroys a number of homes and kills their occupants, including Masagi, the survivor of the fishing-boat, and his mother. Shinkichi, Masagi’s younger brother, escapes the collapsing house. From his hiding place he looks back, and sees something that makes him shriek in terror…

The survivors of the storm are transported to Tokyo, where they testify before a parliamentary committee at the Diet Building. Shinkichi insists that he saw a gigantic animal, while Hagiwara points to the kind of destruction caused, arguing that the houses – and Hagiwara’s helicopter – were crushed from above. Testimony is then taken from the palaeontologist and marine biologist Dr Yamane Kyohei.

The casting of Shimura Takashi as Dr Yamane is deeply significant. One of Japan’s leading actors, at the peak of his artistic collaboration with Kurosawa Akira – he starred in The Seven Samurai the same year, lest we forget – yet here he is, in “just a monster movie”…proof positive, if we needed it, of just how seriously everyone concerned with the making of Gojira took the production. When “Dr Yamane” rises to give his testimony to the committee, those assembled applaud him; I like to think that this was Honda Ishirō’s way of acknowledging the importance of Shimura’s involvement.

The outcome of Yamane’s testimony is the outfitting of an investigative expedition to Ohto Island, which includes a number of reporters, Hagiwara included; a physicist, Professor Tanabiya; Yamane’s daughter, Emiko, who acts as her father’s assistant; and Lieutenant Ogata among the crew. The party’s boat is sent on its way with streamers and cheers and cries of, “Good luck!” – not surprising, considering the fate of every other boat to venture into open water in this film – and its departure is watched intently by a man with an eye-patch and facial scarring. He is identified for us as Dr Serizawa, and his presence on the dock provokes an emotional if rather oblique conversation between Emiko and Ogata.

Our attention is soon focused upon the investigation of Ohto, however, and the discovery that the island has become contaminated with radioactivity—but only in discrete areas, not all over the island as you would expect from fallout. A huge depression in the ground catches Yamane’s attention: slowly, as if stunned by his own thought, he declares it to be a footprint. The depression, too, is radioactive, while lying within it is an impossibility: a trilobite of a species extinct for millions of years, also contaminated with radioactivity. At that moment the local warning bell is sounded. The islanders run to the hilltop; the visitors follow in their wake, although at a loss to know what provoked the alarm. They find out soon enough. Yamane is discovered standing alone, staring into the distance, more awed than frightened; he speaks incredible words:

“Tanabiya, I saw it. A creature from the Jurassic period!”

And with that, as if invoked, a monstrous head appears over the hilltop, and emits the most famous of all movie cries…

Islanders and visitors alike flee to safety. Frantic gesturing draws Yamane and Tanabiya to another vantage point, from where they can look down upon the coastline….and a beach scarred by a trail of enormous footprints, and the sweep of a gigantic tail…

Back in Tokyo, Yamane presents the expedition’s findings to an understandably stunned group of auditors. (We get the film’s single major blunder here, as Yamane describes the Jurassic age as occurring “two million years ago”—although perhaps something got lost in translation, as two hundred million would be closer to the mark.) During his speech, Yamane refers to the creature as “Godzilla”, in acknowledgement of the Ohto folklore, and puts its height at 50 metres. He goes on to suggest that the creature’s sudden appearance is the result of recent nuclear experimentation, which either drastically altered its natural habitat, or otherwise drove it out into the open. Much muttering and some sceptical laughter greets these theories, to which Yamane responds by displaying the trilobite, and describing the radioactive contamination of the sediment found embedded in its shell: sediment that dates from the Jurassic age. With Tanabiya’s assistance, Yamane goes on to explain that the radioactive contamination of Ohto Island, of Godzilla’s footprints, and of the sand found on the trilobite, is specifically Strontium-90—a product of nuclear fission, and a significant component of nuclear fallout…

To this point, Gojira is a fairly obvious melding of its two major influences. We have the islanders of King Kong – not “savages” here, but not so far advanced that they can’t remember a past of human sacrifice and ceremonies of appeasement, either – and a mythic deity that turns out to be only too real. And we have the prehistoric monster, the dinosaur, of The Beast From 20,000 Fathoms, revived or released by atomic testing, and later running amok through a major urban area. So far, so familiar. But with Yamane’s testimony to the Diet committee, the parting of the ways between Gojira and its models could hardly be more absolute.

The first thing we notice is the vastly different attitude of this film to radiation and atomic testing. During the 1950s, “radioactivity” became the all-purpose whipping-boy of American science fiction—but very rarely more than that. Whether creating, or reviving, or sometimes destroying, “radioactivity” was simply the MacGuffin, an excuse to let loose a monster on a highly enjoyable rampage of destruction. The underlying fears that inspired these films might have been real enough, but the result was rarely other than trivial.

The choice of a similar theme in Gojira, conversely, could not be more serious. Dark and powerful emotions underpin every use of, every reference to, atomic energy and its consequences in this film, as with solemn deliberation, Tanaka Tomoyuki and Honda Ishirō set about evoking the horrors of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and the casualties that reached into the hundreds of thousands.

It is certainly no coincidence that the events of Gojira all take place within the month of August. It was a devastation that the director had personally witnessed. Drafted in 1936, Honda Ishirō finished WWII as a prisoner of war in China. His journey home took him through Hiroshima, and changed him forever.

But a more recent incident also had a profound effect upon the makers of Gojira. The opening scenes of the film, showing the blinding light flash and boiling ocean that bring about the fiery destruction of the Eiku-maru and the Bingo-maru, are an explicit and calculated reference to the fate of the Fukuryu-maru – meaning, ironically, “The Lucky Dragon” – which in March of 1954, in an effort to retrieve the fortunes of an unsuccessful fishing voyage, and having received no warning to the contrary, ventured into the vicinity of the Marshall Islands, and was caught in the fallout from an atomic detonation at Bikini Atoll.

The “Castle Bravo” shot, the first test of a fusion-based device, turned out to be three times as powerful as anticipated. It obliterated part of the Atoll, and threw radioactive debris over thousands upon thousands of square miles. On the Fukuryu-maru, the crew witnessed the blast. By the time the ship reached Japan, several members of that crew were already showing symptoms of radiation sickness; the subsequent death of the ship’s radio operator, Aikichi Kuboyama, provoked mass demonstrations from the Japanese people and gave birth to a protest movement that very nearly brought down the government. It was later determined that around one hundred fishing boats had been exposed to the fallout, along, of course, with much of the indigenous population of the Marshall Islands.

During the Allied Occupation, both the conventional and the atomic destruction of Japan’s cities were a forbidden subject. When the occupation ended, the pro-U.S. government continued to discourage any direct reference to these events. A few film-makers chose to ignore this edict, but for the most part the result was tentative, “after the event” efforts that displayed a distinct uncertainty about the handling of their subject matter. (The exception is Sekigawa Hideo’s Hiroshima, which bluntly accuses the US of using the Japanese people as nuclear guinea-pigs.) Against this backdrop, Gojira is an extraordinarily explicit work, an example – indeed, the perfect example – of a film that is “just” a monster movie, “just” a horror movie, saying far more than its serious dramatic counterpoints dared to, and getting away with it.

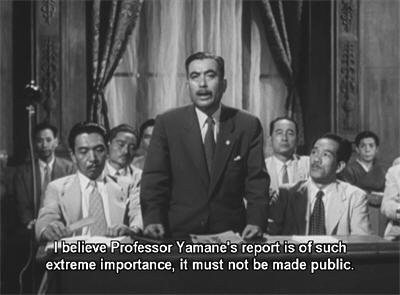

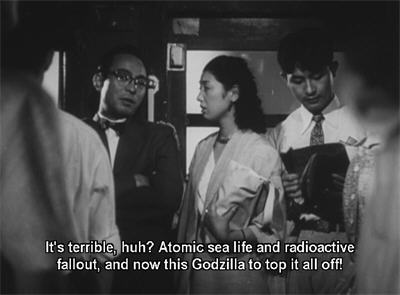

If the first half of Gojira is somewhat derivative, from the point of Dr Yamane’s address it becomes a remarkable and individualistic work inspired by little beside the sensibilities of its makers. A fascinating scene follows Yamane’s announcement that Godzilla has not merely survived a nuclear blast, but has somehow absorbed the radiation. Mr Ooyama, the chair of the parliamentary committee hearing testimony about the events on Ohto, instantly declares the news too serious to be made public; that the announcement not merely of Godzilla’s existence, but that he is in some way the product of atomic testing, would assuredly throw the population into panic. The rest of the entirely male committee applauds this declaration approvingly. The gathered reporters, however – led by an extremely mouthy trio of women, one of whom does not hesitate to call Ooyama an idiot – aren’t having a bar of any cover-up. They get their way. The newspapers reveal the truth to the public, and we cut to some ordinary citizens discussing the news on a train, frightened and bewildered, but calm. One makes wry reference to surviving Nagasaki; another sighs with grim resignation, “The shelters again…” Was this scene intended as a criticism of the government for under-estimating its people? Perhaps—but on the other hand, it is clear that the citizenry has yet truly to grasp what is in store for them; certainly not those people spending an evening on a drinking-and-dancing boat upon Tokyo Bay…

(Another interesting touch to be found at this point of the film is the unofficial adoption of the orphaned Shinkichi into the Yamane family; a fate similar to that experienced by many real war orphans.)

In the meantime, the government dispatches the “anti-Godzilla frigate fleet”, to drop depth charges in the creature’s vicinity: an historic moment, the first but far from the last failure of conventional weaponry against its most famous foe. (With sixty-odd years’ hindsight, watching these scenes, and those in which the soldiers fire standard machine-guns at Godzilla, is enough to make you cry.) The effectiveness of this ploy is revealed when Godzilla makes his first ever appearance in the vicinity of Tokyo, rising up out of the bay and splashing his way across, but doing no immediate damage—even to the party boat. Dr Yamane is again summoned to speak with the government officials, who plead with him to be frank, if he can suggest any way that Godzilla can be killed.

Dr Yamane, of course, doesn’t want Godzilla to be killed at all—not, I would argue, an unreasonable stance for a palaeontologist and zoologist confronted by a living dinosaur, certainly not at this point in the story. The one single tiny sliver of humour to be found anywhere in this film comes when Ogata works up the nerve to tell Dr Yamane about himself and Emiko, and ends up being ordered from the house—not for his intentions towards Emiko, but for declaring that he agrees with those who say that Godzilla must be destroyed. We should note, however, that Yamane says nothing more about it once Godzilla really begins to (ahem) stomp Tokyo.

Nor is Yamane’s initial hope that Godzilla can be preserved a simple desire for the survival of a unique specimen. When the officials ask Yamane to suggest a way of killing the creature, the scientist is blunt. “Godzilla absorbed massive amounts of atomic radiation: what do you think could kill him?” Yamane’s argument is that Godzilla’s ability not just to withstand but to absorb radiation, even to thrive upon it, must be studied and understood.

Here we cut back to the reporter Hagiwara, assigned full-time to Godzilla’s story, and on a lead dispatched by his editor to interview another scientist, Dr Serizawa Daisuke, who rumour claims to be the creator of a weapon powerful enough to destroy even Godzilla.

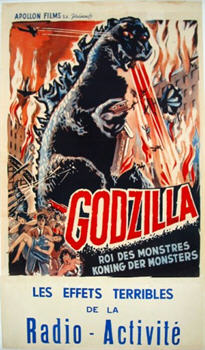

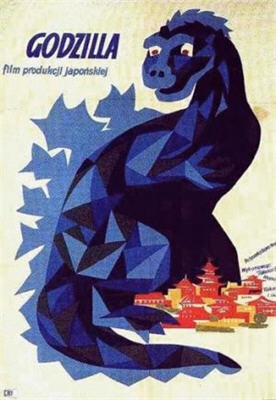

There are many ways in which the gap between the American and the Japanese perspective makes itself felt over the course of this “monster movie”, but nowhere more so than in Gorija’s presentation of Dr Serizawa. Serizawa is first glimpsed silently watching the departure of Dr Yamane and his team on their expedition to Ohto; and in any other movie, his eye-patch, his sunglasses, his facial scar, his grim expression and his dark suit would be enough to mark him as the villain. (And while we’re on the subject, look at the way that Serizawa’s image is used on the poster.) It is a commonplace of American monster movies for the hero to be one of the first people to become aware of the existence of the monster – or at least, to do so and survive – and generally speaking, we follow him from first encounter to final destruction, in which more often than not he is involved, either directly or by coming up with the plan. The Beast From 20,000 Fathoms itself takes this road. Our familiarity with this schema makes Serizawa’s deferred introduction in Gojira seem anomalous, as indeed does the oblique way in which the character has been referenced to this point; because Serizawa is, inarguably, the hero of Gojira—and ultimately, one of cinema’s most moving and tragic heroes.

A further dissimilarity between this film and many of its American counterparts is its handling of its central love triangle; that is, what we, perhaps belatedly, perceive to be its central love triangle. It is another American commonplace for the heroine of a monster movie to be caught between two male co-leads, but ending up with one of them by the end, either because he has proven himself “the better man”, or because his rival has sacrificed himself along the way. Although something generally similar happens here, its specifics could hardly be more different. It is evident from the outset that there is something between Yamane Emiko and Ogata Hideo, although this being a Japanese movie of 1954, we neither expect nor receive much physical or verbal confirmation of this fact. That something is bothering the two of them is also clear; what, exactly, remains undisclosed until Ogata reacts uncomfortably to Serizawa’s presence at the departure of the expedition. It is Hagiwara’s editor who finally declares Serizawa to be “Dr Yamane’s future son-in-law”…at almost the same moment that Emiko is assuring Ogata that she thinks of Serizawa as a brother, and always has.

When Hagiwara comes to Emiko to beg her to get him an entré to Serizawa, she seizes the opportunity to visit him herself, determined to tell him about Ogata and formally to break their engagement. It doesn’t quite work out like that. Serizawa stonewalls Hagiwara and his inquiries about a new weapon, and eventually the reporter gives up. When he has gone, however, and Emiko herself puts off carrying out the real reason for her visit with questions about Serizawa’s research, the scientist abruptly offers to show her what he is working on. It is a demonstration that leaves Emiko overcome with horror. As she staggers from the laboratory, Serizawa demands from her, and receives, a solemn promise that she will tell no-one of what she has seen—no-one. There is an air of discomfort about Emiko here that has nothing to do with what she has seen. We understand that she is thinking of another solemn promise that she once made to Serizawa.

And that night, Godzilla emerges from Tokyo Bay, destroying a train and knocking over some bridges in the dock area of the city before vanishing back into the water. There is an immediate response from all over the world, as researchers fly in with offers of assistance and advice. The upshot is the evacuation of the coastal population, and the construction of an electrical barrier about the city carrying 50,000 volts (erected on the conviction that Godzilla will be back…and of course, they’re right). The evacuation serves its purpose, but the only effect of the barrier is to annoy Godzilla into deploying his radioactive breath: one of the most indelible moments amongst so many in this sequence. What follows is perhaps the greatest monster rampage ever put on film, as Godzilla sweeps aside the combined power of Japan’s armed forces, and reduces Tokyo to a state of utter ruin.

It can be easy to forget, particularly if you’ve been watching any of the later, pop-art, good-guy-Godzilla movies in between viewings, just what a grim and disturbing film Gojira is. Even the more serious American monster movies, and the later Japanese ones (including the subsequent Godzilla films), at least tacitly encourage the viewer to take a Schadenfreude-ish pleasure in the destruction of their various landmarks and cities; while many, perhaps most, such movies serve up their carnage in clear expectation of provoking nothing beyond cheers and laughter.

But not Gojira, unique in the gravity and sincerity of its intentions. There is not a single instant in this film when the viewer is invited simply to enjoy the spectacle. Rather, it demands a profound emotional response: horror at the devastation, and pity for the victims; all of it underscored by our knowledge of what inspired this story’s production.

Amongst all the unforgettable images here are two brief scenes immortal in the kaiju lexicon. In the first, a woman, a widow, comforts her three small children by telling them that soon they’ll be with their father again—very soon. In the other, reporters watching from a broadcasting tower attract Godzilla’s attention with their lights. With nowhere to run as the creature moves towards them, the leading radio-man continues his report right up to the instant of the tower’s destruction and his own death. This iconic sequence, so often afterwards referenced either in a direct play for laughs, or so ineptly executed as to provoke laughter, is powerful and moving here.

And then Gojira does something else that separates it from its brethren: it stops to count the cost. We’ve seen Godzilla’s destruction of Tokyo, and we’ve seen the casualties resulting amongst the armed forces, crushed by falling buildings or vaporised by the creature’s breath; but now the film shows us the civilian toll; and if to this point its imagery has referenced the atomic destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, here it evokes rather the firebombing of Tokyo that preceded it. The dead and the dying lie in rows; injured children scream for their mothers; doctors and nurses struggle helplessly with wave upon wave of casualties. A small boy is scanned with a Geiger counter, as his doctor slowly shakes his head…

Throughout all this, we have stayed with the Yamane family and Ogata, seeing the destruction through their eyes. In the aftermath, Emiko works as a volunteer at a hospital—and what she witnesses there brings her to a critical decision: that it is time she broke her second promise to Serizawa. Emiko tells her story to Ogata, and in flashback we see what happened in Serizawa’s laboratory; what it was that caused the scientist to demand from Emiko so solemn an oath of secrecy.

Within Serizawa’s laboratory is a large fish-tank; a new addition since Emiko’s last visit, evidently, since she exclaims at its presence. Donning thick protective gloves, Serizawa drops a small pellet into the tank. He then pulls Emiko back to a safe distance as the water begins to churn—and as the fish within the tank are completely skeletonised, their flesh liquefied as Serizawa’s discovery extracts from the water and their bodies every last vestige of oxygen… A single piece of this “oxygen destroyer”, comments Serizawa, dropped into Tokyo Bay, would turn it into a graveyard.

Emiko and Ogata’s visit to Serizawa is Gojira’s eye-of-the-storm, a period of comparative calm bookended by nightmarish scenes of destruction and mourning. One of the real strengths of Gojira is the way it balances its humanitarian aspects with its sense of proportion. Thus, while we follow the story largely from Ogata and Emiko’s perspective, while their romantic difficulties and desires are always somewhere in the frame, their personal story is never allowed to dominate—and nor is there ever that obnoxious implication, so common in films of this kind, that as long as these particular people are okay, then everything’s all right, that the story has a happy ending. In the overall scheme of things, Ogata and Emiko’s problems don’t amount (as we might say) to a hill of beans, and it is to the credit of everyone involved that this is acknowledged so clearly. Indeed, it is not the Emiko-Ogata romance, but Emiko’s involvement with Serizawa, that really carries weight. It is via this doomed relationship that we come to understand the scientist.

Audiences used to the emphasis given to the love story in most Western films may find its equivalent here strangely diffuse. The circumstances under which Emiko became engaged to Serizawa, for instance, are never referred to; there is no scene in which she justifies herself to Ogata. Whether it was duty to her father, or affection, or hero-worship, or a combination of all three that led Emiko to enter into her engagement is never revealed. It is, in any case, easy enough to imagine the effect that Serizawa’s return from the war, severely wounded in both body and mind, would have had upon Emiko and her father, both of whom clearly hold him in the deepest respect.

Through the tentative interaction between Emiko and Serizawa, the scientist begins to be revealed, and the depth of his tragedy becomes clear. Despite his dedication to pacifism, his desire to work for the benefit of mankind, Serizawa’s war-time experiences have left him emotionally scarred to the point where an ordinary life is beyond his capability. There is a real sense that Emiko represents a kind of life-line for Serizawa, his last tenuous link with normality. It is also quite possible that Emiko realises this herself, and that it is this, rather than any feeling of duty or guilt, that lies at the root of her reluctance to break with him.

Hirata Akihiko’s performance as Serizawa is a wonderfully nuanced piece of acting, allowing our sympathies, even our affections, to lie with the scientist even as we recognise the extent to which he is psychologically damaged. Given the origins of this film, we do not expect any intimate contact or conversation between Emiko and Ogata. However, Ogata is forever putting his hands on Emiko’s shoulders, while on Ohto, as the two of them are fleeing from Godzilla, he does take her protectively into his arms. Conversely, the critical moment between Emiko and Serizawa is that in which he reveals his work to her. We recognise that his doing so is a gesture of trust and affection, the only kind, perhaps, of which he is capable—but we recognise also in its outcome the impossibility of any future between the two. Significantly, the only physical contact between the two occurs here, as a horrified Emiko hides her face against Serizawa’s shoulder after recoiling in revulsion from what he has shown her.

The debate between Serizawa and Ogata, in which the latter pleads for the “oxygen destroyer” to be used as a weapon against Godzilla, cuts to the moral heart of this story. Serizawa himself has already made his feelings on the subject quite clear, expressing to Emiko his recognition of the dangerously dual nature of his discovery: his determination to harness its power for the benefit of mankind, and his profound fear that, in other hands, it might instead be used as a weapon—a weapon even more terrible than the atomic bomb. But Serizawa’s fears are more specific even than that. His overriding terror, confessed here under the pressure of Ogata’s urging, is not just that his work will be put to destructive and violent purposes, but that he himself will be instrumental in it happening; that he will be coerced, or tricked, or tempted, into allowing his discovery to be used against humanity.

And perhaps Serizawa knows that he has reason to doubt himself. His initial reaction to Ogata’s plea is a flat refusal. He flees to his laboratory and locks himself in, and by the time Ogata and Emiko force their way in, he is trying to destroy his experimental notes. A struggle between the two men ends with Serizawa knocking Ogata down and injuring him—and it is this impulsive act of violence that stops the scientist in his tracks, and gives the advantage back to Ogata. As Emiko tends his injuries, Ogata argues passionately that while he understands Serizawa’s reluctance, what he fears is what might happen in the future, while Godzilla is mankind’s immediately reality; that here the oxygen destroyer, although used as a weapon, will be used to benefit humanity. Serizawa counters that once knowledge of the oxygen destroyer is made public, the genie will once again be out of the bottle—and that it will only be a matter of time before someone does use it against humanity.

It is not difficult to read the film-makers’ own bitter and outraged feelings here, lurking behind Serizawa’s ethical terrors; but perhaps in this respect Gojira isn’t entirely fair. Serizawa, after all, is a private individual. He does not work for the government; he is not part of a team; and he is not carrying out his work under constant surveillance, and under threat of professional and personal ruin. The responsibility is entirely his—and so, ultimately, is the choice.

As Serizawa almost collapses under the weight of his moral dilemma, clutching his head as he cries in agony, “What am I going to do!?”, an answer comes in the form of a special television broadcast of a children’s choir singing “Oh Peace, Oh Light, Return”, an anti-war song used here as a prayer. The song is accompanied by images of a city in ruins, and of Godzilla’s victims. Serizawa watches, and accepts his responsibility—and his fate.

As Serizawa’s quandary is resolved, so too is the Ogata-Emiko-Serizawa triangle. The beginning of the argument over the oxygen destroyer, with Serizawa reacting in outrage to Emiko’s betrayal of his secret, and both Ogata and a tearful Emiko pleading for his forgiveness, is curiously double-edged. Although Emiko’s other betrayal is never touched upon, the significance of her choosing Ogata for her confidante certainly does not escape Serizawa. By the time the debate over the oxygen destroyer has concluded, all three of them know exactly where each of them stands—and without one direct word being spoken on the subject.

When Serizawa returns calmly to burning his notes, Emiko breaks down in sobs, understanding only too well the implication of the scientist’s quiet declaration that this is the only time the oxygen destroyer will ever be used. We then cut to a ship on Tokyo Bay, with Geiger counters being used to locate the submerged Godzilla. Another two-edged conversation takes place here, as Dr Yamane and Ogata try to persuade Serizawa that Ogata, an experienced diver, should be the one to take the oxygen destroyer down, and Serizawa countering that he is the only one who knows how to use the device correctly. Finally a compromise is reached when Ogata insists upon accompanying Serizawa. As both men don their diving-suits, poor Emiko can only look on helplessly…

And so Ogata and Serizawa descend to the floor of Tokyo Bay; and if we had any doubt about the depth and breadth of Gojira’s humanitarianism, we have it here as its compassion reaches out to embrace even the destructive power at the centre of its story. Here, for the first and last time, we catch a strangely touching glimpse of Godzilla at peace, going about the normal life from which forces beyond his control or understanding have so violently wrenched him. Even in the face of all the death and chaos, even as mankind strikes back with a power even more terrible than Godzilla himself, the film takes a moment to remind us that Godzilla, too, is in his way a victim.

With their target located, the men signal the boat. Ogata begins his ascent, but Serizawa does not follow.

As the oxygen destroyer begins its terrible work, Godzilla writhes in agony, breaking the surface of Tokyo Bay and uttering a haunting death-scream before collapsing and sinking to the floor of the bay, nothing but a skeleton left behind…

And Serizawa, having witnessed the full realisation of his deepest fears, sends to the surface one final wish for the future happiness of Ogata and Emiko, and cuts his own air-line…

Gojira is a remarkably powerful film. It is also, and this above all else, an overwhelmingly sad one. The twin deaths at its conclusion, man and monster equally victims of a terrifying force, create a climax of astonishing emotional impact. Yet having reached this point, Gojira still does not relent. There is some celebration of Godzilla’s death, but it is brief, undercut by mourning for the man whose self-sacrifice made it possible. Emiko and Ogata, Hagiwara and Shinkichi, all weep openly. And even as he grieves for Serizawa, Dr Yamane insists that this victory, if victory it can be called, is only temporary; that the forces that produced one Godzilla will inevitably produce another, should man continue on his reckless path…

It can be difficult today, with Godzilla one of the true icons of world pop culture, to understand the magnitude of the risk that Toho Studios took in producing Gojira. First and most simply, there was the financial risk. The film was budgeted at roughly three times that of a standard production, with all that money being poured into an unproven genre, a new kind of movie in both style and execution. Then, of course, there was the political risk. The decision to ignore government edicts against nuclear-themed movies was dangerous enough; for many viewers, the film’s deliberate and unrelenting evocation of the horrors of nuclear war was too much, and the film-makers found themselves facing accusations of exploiting the national tragedy for gain. This response is understandable, but misguided. Few films are as pure in their intentions as this one.

As with many great films, Gojira was to some extent the result of serendipity. If Tanaka Tomoyuki’s Indonesian project had not fallen through, if his first-choice director had accepted the assignment…well, who knows? A large measure of the film’s success is also due, ironically, to limitations imposed upon its production by both circumstance and budget. Both of Gojira’s models, King Kong and The Beast From 20,000 Fathoms, realised their monsters via stop-motion; but neither the technical expertise necessary nor the time to execute this particular form of animation were available to the makers of this film. Instead, Tanaka Tomoyuki and his special effects man, Tsuburaya Eiji, came up with something that goes by the rather overly grand title of “suitmation”—in other words, they put a man in a suit. Stuntman Nakajima Harou, with occasional relief from his fellow technician Tezuka Katsumi, was given the job of bringing Godzilla to life. Although suffering agonies courtesy of the combination of the heavy, airless rubber suit and the blazing studio lights, Nakajima gallantly completed his assignment, part of which was the destruction of a convincing miniature Tokyo also constructed by Tsuburaya Eiji.

(Among the landmarks falling to Godzilla in this sequence are the Diet Building and the Wakko Building clock tower; the creature’s now-trademark target, the Tokyo Tower, was not built until 1958.)

The long shots of Godzilla are impressive; the close-ups, which rely upon a rather awkwardly constructed puppet, are less so. It is fair to say, I think, that Godzilla rarely ever looked worse than he does in our very first glimpse of him, peering over the hilltop on Ohto Island. It is noticeable, however, startlingly noticeable, that the Godzilla of Gojira is not the Godzilla with whom most of us are by now familiar. This is a more disturbing incarnation, far more animalistic and entirely free of the anthropomorphism that slowly engulfed him over the course of his subsequent career. With glittering black eyes, clawed hands and an utter disregard for everything and everyone in his way, unstoppable except for the deployment of a weapon even more terrible a power than he, this original Godzilla is a dark and frightening creation, every inch the believable offspring of dark and frightening forces.

The decision to shoot Gojira in black-and-white was critical to the film’s success. Although this was almost certainly done in order to disguise the shortcomings of the suit, and of some of the model work, the usual black-and-white side effect, a gritty cinéma-vérité quality, heightens enormously the film’s realism and dramatic impact. Honda Ishirō’s background in cinematography and documentary-making, as well as his own war-time experiences, is evident throughout the film, but particularly in the staging of the attack upon Tokyo.

The other artistic triumph of the film is its score. While the stirring martial themes of composer Ifukube Akira would before long become the de facto signature of the entire kaiju eiga genre, the deep, ominous rumblings that precede Godzilla’s appearances, and the haunting and elegiac composition that plays softly during some of the film’s more moving human scenes, are equally potent. The use of the latter during the final underwater sequence, as Serizawa goes to meet his destiny, is quite heartbreaking. But in paying tribute to his score, we must not overlook the composer’s contribution to the film’s sound effects, which are in their own way just as important. By dragging a leather-gloved hand over the slackened strings of a bass fiddle, and altering the tempo of the sound in playback, Ifukube Akira would succeed in creating the single most famous cry in all monster-dom.

Although not welcomed in all quarters upon its release, Gojira’s critical reputation in Japan has grown ever stronger with the passing years, until today it regularly turns up on lists of the greatest Japanese movies, rubbing shoulders with the likes of Rashomon and Sansho Dayu and Tokyo Monogatari. While from a certain perspective this may seem outrageous, one need only look past the “just a monster movie” façade, to the power of the message beyond, to see how this could come about.

Sadly, for many, many years the rest of the world was denied the opportunity to see Gojira for themselves—at least in its original form. Starting a trend that, incredibly, continues right to this day, producers Harold Ross and Richard Kay acquired the rights to Gojira and re-shaped the film to their perception of American tastes. The problem was, Ross and Kay didn’t want a “message” film; and they certainly didn’t want one where the message was of the anti-nuclear persuasion. Nor, they imagined, would the American public in general be very interested in an out-and-out Japanese movie. What everyone did want was, well, “just a monster movie”. The producers’ solution to their dilemma was perversely brilliant: hiring Raymond Burr, then just making a name for himself as an actor (he was in Rear Window the same year), they re-structured the story of Gojira so as both substantially to tone down its nuclear doom-saying, and to place an American identification figure at the heart of the action.

To give the devil his due, Godzilla, King Of The Monsters is by far the best and the most honest of all the kaiju eiga “Americanisations”. Even edited and re-focused as it is, and with Raymond Burr playing Greek chorus as reporter-witness Steve Martin, much of the film’s power remains. It is still an incredibly bleak story, not “fun” at all in the usual monster movie sense. And for many years – in America, for a full fifty years – this was the only way most people outside of Japan knew the film. (We in Australia benefited from the then-policy of TV station SBS, which brought the original version, uncut and subtitled, to our screens in the early 1990s.) It was not until its fiftieth anniversary, celebrated by the worldwide DVD release of both versions of the film, that many people saw the real Gojira for the very first time: an enormous shock, and an even greater revelation.

There are, I suppose, some people out there so soulless that they can look at Gojira and see nothing except a guy in a rubber suit stomping on miniatures. You can only pity their lack of imagination—and their lack of heart. For myself, when watching Gojira I generally start to tear up in the middle of the destruction of Tokyo, and by the time of its climactic double tragedy, I’m a complete emotional wreck. Gojira really is unique. No other anti-nuclear film is so accessible, so easy to love; no other “monster movie” is so profound. None of Godzilla’s progeny, and they are legion, can touch their old man.

And in an odd sort of way, the film’s climax is even harder to take today than it was originally. As painful as that ending was when Godzilla was so completely a force of destruction and death, these days, when we have nothing but love in our hearts for the big guy, it’s simply agonising. (It remains, and I suppose I can put it like this, the most unambiguous Godzilla death.) And this fact leads us to contemplate a bewildering contradiction, in the cultural devolution of the symbol of the most terrifying power ever unleashed against mankind into a cuddly pop art icon infamous for his swagger, his tail-propelled acrobatics, and his dubious parenting. Perhaps the best we can say about all this is that, in turn, it symbolises the enduring capacity of the human spirit to come to terms with almost anything—even with the vision of its own imminent annihilation.

*************************************************************************

This review was part of RUBBER SOUL, the B-Masters’ tribute to the men in the suits.

I love all the all the varied ‘sweaty guys in suits’ Kaju films but Gojira started it all and will always be the best. I loved your detail in the gathering of the production team and the thinking going into the making of the film. Most discussions never go much further than the story of the director looking out the window of his plane at the ocean and thinking about a monster.

I was so excited this year that Godzilla Returns, aka Godzilla 1985, aka Gojira was finally released in the US on DVD and BR. Toho so hated the Americanized version they never released it after the initial VHS releases. They did an entire new English dub so no annoying Raymond Burr Dr. Pepper Commercials in the film.

LikeLike

I, too, am excited to see Godzilla Returns the way it was meant to be. Godzilla ’85 has a soft spot as my first G film (and for a long time I thought it’d be the only one I’d see in a theater), but when I rewatched it years later, it did not hold up too well. I don’t know if the differences will be as dramatic as those between Godzilla’s Counterattack/Gigantis the Fire Monster, but I can only imagine it will be a more enjoyable experience.

Speaking of which…knowing Lyz, that’ll be the next review she uploads here. And then she’s going to surprise us with her long-awaited, fully-updated King Kong vs. Godzilla review. Right, dear? 😀

For now, though, I’m going to reread what’s probably my favorite Lyz piece, and then no doubt watch this movie for the umpteenth time, even though it means I’m going to start crying at some point.

LikeLike

I’m in the process of writing a 15-page academic paper about the Big G (I’m in grad school)… I had no idea Godzilla ’85 was about to be released (finally) on Blu Ray, let alone the original uncut version. w00t, as the kids used to say!

LikeLike

Wrong! You’re in the right ballpark, but you need to expand your search parameters. 🙂

Fun fact: it *is* possible to make yourself cry watching a film piecemeal for screenshots. Also to fire up an already intense crush…

Yes, this is one of my favourites, too; one of those all-too-rare pieces of writing where you manage to say everything you meant and have it come properly together.

LikeLike

Oh, I just said that because I want more Godzilla reviews from you. Both of yours were superlative. Or even better, have you leap into the Heisei Gamera trilogy. And not just because you’d cover my second-favorite giant monster movie ever. (I still can’t believe a Gamera movie took that spot.)

Hmmm. “Right ballpark” would indicate a giant monster movie, of which you’ve only reviewed a few. However, the only crush of yours I recall is Chow Yun Fat; the only movie of his I remember you reviewing was the crazy awesome Dr. Yuen and Wisely; and other than that recipe he gives for the blood bath I can’t think of anything that would make you remotely sad in that. And I definitely can’t remember a movie that had you weeping AND crushing…well, I may just have to wait and see.

LikeLike

No, no—I was weeping *and* crushing while watching Gojira. 🙂

So yeah, more monsters on the way (hopefully), just not The Big Guy.

LikeLike

I have three guesses on your crush here. I have a feeling number one is the correct one. I’ll wait to see what your answer is.

I certainly hope for more monsters, too! I’m always hoping for the revised KKvG based on the idea that it’ll lead to more Godzilla reviews. I would love to see your take on Son of Godzilla (the one I’ve gotten more flack for loving than any other; plus, giant creepy-crawlies, and SCIENCE~!!!) and a perverse desire to read your thoughts on Godzilla vs. Megalon.

As it turns out, I haven’t even needed to rewatch the movie to start crying; rereading your review did it. This go-round, it was when “Oh Peace, Oh Light, Return” started playing in my head at the appropriate moment.

LikeLike

I don’t think there’s much mystery about it, is there!? 🙂

{*fans herself vigorously*}

LikeLike

Okay, not really; that was my first pick by a very comfortable margin. There was an outside chance of Ogata or even Dr. Yamane, though.

LikeLike

Dr Yamane would certainly come in second; we could shake our heads over Emiko and her poor taste in men together. 🙂

LikeLike

Hi, Kit – thank you! I agree, this film is in a completely different league from all the others, not that I don’t love those too!

I’ve only seen the Dr Pepper version so I’m very excited too! (Noting that we don’t have Dr Pepper in this country…)

LikeLike

Oh such a shame, Dr. Pepper is a great drink. I like it a lot but they really laid it on thick in that movie. Product placement has its place but come on, keep it subtle.

LikeLike

Pingback: Review: Shin Gojira (2016) | Mike's Movie & Film Review

Pingback: Gojira | Scifist

Monday, I went to re-watch this in a theater, which I first got to do 15 years ago. Pretty sure it’s the same print they used back then, too.

Tuesday, I re-read my favorite review from my favorite reviewer. I love how you get it, so completely.

Today, I posted about it under the appropriate review.

The end.

LikeLike

But the big question is—DID YOU CRY AT THE END??

Thank you very much, m’dear.

I may say I am as happy with this piece as with anything I’ve ever written—full credit for which must go to the film, of course.

LikeLike

Oh, my sweet Lyzzy…you don’t really have to ask if I cried, do you?

And you’re only too welcome. It was a pleasure to revisit this.

LikeLike

Just as well for you.

If there’s one thing I despise, it’s a man who isn’t tough enough to cry…

LikeLike

I have never been truly thankful that I cry when I watch this movie until this moment. 😀

LikeLike

I thoroughly enjoyed this detailed, insightful review of the orignal “Gojira” (which I have seen twice so far, most recently yesterday). I have come to love this film, not only because of the well-done monster-on-a-rampage theme, but moreso because of the allegorical elements and the portrayals of human conflict and emotion at various levels (islanders, citizens, scientists, military, news reporters, politicians). All the performers are excellent; the beautiful ending is both prophetic and elegiacal. This is a dramatically compelling film.

LikeLike

Thank you so much! Of course I agree with you entirely about this wonderful film. 🙂

LikeLike

Pingback: Gojira – scifist 2.0