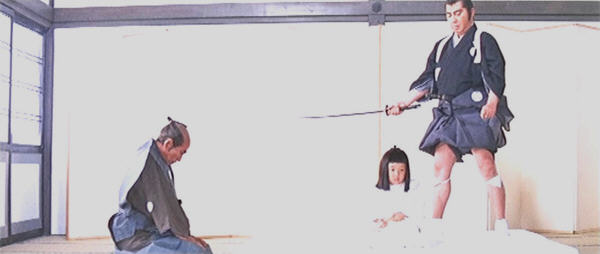

“Daigoro, the road you will take shall be chosen by you alone. If you choose this sword, you will travel the road of the assassin, with me. If you choose this handball, I will send you to be with your mother…”

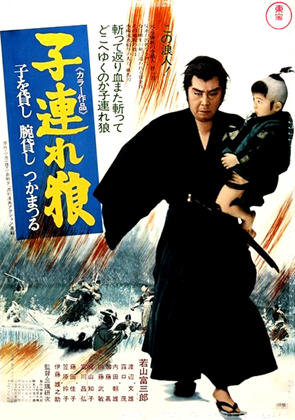

[Original title: Kozure Ōkami: Kowokashi Udekashi Tsukamatsuru (Wolf With Child In Tow: Child And Expertise For Rent)]

Director: Misumi Kenji

Starring: Wakayama Tomisaburō, Tomikawa Akihiro, Mayama Tomoko, Itō Yūnosuke, Naito Taketoshi, Kasahara Reiko, Watanabe Fumio, Fujita Keiko

Screenplay: Koike Kazuo, based upon the works of Koike Kazuo and Kojima Goseki

Synopsis: Ogami Ittō (Wakayama Tomisaburō), former Shogunate executioner, wanders the countryside with his young son, Daigoro (Tomikawa Akihiro), whom he pushes in a wooden cart, hiring himself and his child out to anyone who can pay for their services. An elderly woman rents the child, so that her daughter, driven insane by betrayal and the death of her own baby, can breastfeed him. Ogami refuses payment, as this transaction provided a meal for Daigoro. It begins to rain. Covering his child, Ogami thinks back to another rainy day two years earlier… Ogami’s wife, Azami (Fujita Keiko), confesses to him that she has been suffering a recurrent dream about the spirits of those that he has executed. Ogami takes the baby Daigoro and goes to his personal shrine, where he performs a ceremony to honour the dead. In his absence, a band of assassins breaks into the house. Ogami hears Azami’s cries of agony, and runs to the house. Azami lives long enough only to touch her son’s cheek with bloody fingers, then dies in her husband’s arms. Ogami discovers that the rest of the household has been murdered as well; he swears a terrible vengeance… Even as he grieves, Ogami receives an official visit from Superintendent Bizen (Naito Taketoshi), who is of the Yagyū clan. Bizen tells him that three samurai accused him of treason against the Shogun, claiming that evidence could be found in his shrine, and then committed seppuku as proof of their sincerity. Within the shrine, Ogami is stunned to find the Shogun’s mortuary tablet. He then realises that the Superintendent’s men have armed themselves, and put on sword-proof mail. In a fury, Ogami accuses Bizen of plotting against him, and of being one of the “Shadow Yagyū”. Led by Retsudō (Oki Yūnosuke), this is an offshoot of the genuine Yagyū clan, whose members are using treachery and murder to bring themselves into positions of power. Admitting the plot, Bizen orders his men to kill Ogami, but the swordsman slaughters his adversaries. Ogami sees Retsudō watching from a distance, and again swears that he will have revenge… Ogami and Daigoro enter a small village, where Ogami is hired to dispatch four treacherous samurai and their band of mercenaries, who plan to kill the rightful heir to the local fiefdom’s throne and establish a puppet government. As Ogami sets out on his mission, he sees two children playing with a ball. This triggers more memories… Convicted of treason and ordered to commit seppuku, Ogami makes a fateful decision: he will defy the Shogunate’s decree and become a paid assassin, until he can fulfil his vows of vengeance against the Yagyū. But what of the infant Daigoro? Grimly, Ogami places before the child a sword and a ball. If the boy chooses the former, he will become an outcast like his father; the latter, and he will be sent to join his mother…

Comments: Sword Of Vengeance was the first of six films adapted between 1972 and 1974 from the incredible 110 volume manga by Kazuo Koike and Goseki Kojima, films that are generally known collectively as the “Lone Wolf and Cub” or the “Baby Cart” series. Upon a first viewing, Sword Of Vengeance often strikes viewers as both strangely familiar, and strangely unfamiliar. During the late seventies, Roger Corman’s New World Pictures acquired the rights to both Sword Of Vengeance and the second entry in the series, Baby Cart At The River Styx. The two films were edited, the footage cobbled together and dubbed, and the result released to Western audiences as Shogun Assassin.

Somewhat ironically, this patchwork effort probably turned far more people onto Asian cinema than the “pure” version of either film could have done on its own, by providing an astonishingly compressed view of just how extreme Asian cinema could be. When the two films were cut together, what was kept was, of course, “the good bits”—that is, the incredible fight scenes that make up a portion of Sword Of Vengeance, and a great deal of Baby Cart At The River Styx. It comes as no surprise therefore that far more of the latter film than the former ended up in Shogun Assassin. And indeed, so very good were those “good bits” that Shogun Assassin eventually found itself caught up in the British “Video Nasty” furor of the mid-eighties.

Conversely, what ended up on the cutting-room floor was the “boring stuff”, the background material that introduces the audience to its anti-hero, Ogami Ittō. While Shogun Assassin found a clever way of telling its story without diverting from the action too much (the film is narrated by the child, Daigoro; his voice is provided by, of all people, Sandra Bernhard!), the fact is that the stories of Shogun Assassin and Sword Of Vengeance are quite different.

It is possible to watch Sword Of Vengeance, and indeed the entire “Lone Wolf and Cub” series”, purely for the action scenes – and I imagine that a lot of people do so – but to ignore the story elements is to rob this saga of much of its richness. To be appreciated, the Lone Wolf must first be understood, and for modern audiences, particularly Western audiences, this is not a simple matter

One of the main features of the Edo period of Japanese history was the emergence of Neo-Confucianism, a particularly secular form of orthodoxy that was introduced to Japan by Ieyasu Tokugawa during his Shogunate. Among other things, Neo-Confucianism had a huge impact upon the place of the samurai in Japanese society. Formerly little more than an uncultured fighting force, the samurai were suddenly raised to a level of privilege, and made a social caste of their own, one responsible for setting an example of devotion to duty, and of unswerving honour and morality.

(Something not readily apparent during Sword Of Vengeance is that this period in Japan’s history was essentially one of peace; the changes to the role of the samurai were made primarily because the warrior class no longer had much to do.)

Society at this time was divided into four separate classes: the samurai, the farmers, the artisans and the merchants; outcasts of society, the eta, formed an unofficial fifth class. The story of Sword Of Vengeance manages to encompass all of these levels of society, as the narrative moves from Edo itself, through various towns and villages, then ends up at a spa patronised by samurai in poor health. As we follow the Lone Wolf on his journey, we meet his evil counterparts, the Shadow Yagyū, who exploit the honour of others; many loyal fiefdom officials; various ronin, rogue samurai; merchants; villagers; bandits; and last and least (or so it seems at first), a prostitute.

Sword Of Vengeance opens, however, at the court of Edo, where the viewer is immediately confronted with a shocking manifestation of the prevailing code of honour, and the way that it dictated life and death. We are introduced to Ogami Ittō in the performance of his duty as Shogunate executioner, “helping” a condemned prisoner to commit seppuku. The prisoner is nothing but a child, scarcely more than a toddler, who is almost lost amongst his white death robes, his bewildered expression leaving the viewer distressingly uncertain whether he understands what is happening or not. As his kneeling vassals weep, the child sits motionless, unresisting. Ogami then steps up behind him and draws his sword…

Even though this is the one act of violence in Sword Of Vengeance that is not depicted explicitly, it is one of the film’s most disturbing. It also illustrates the magnitude of the task that the film sets before the viewer, who must come to terms with a time and a society when the slaughter—sorry, the execution of small children (or “terminating the bloodline”, as the Shogun himself puts it) was an accepted thing; when the post of executioner was not only an honourable one, but so desirable that others would commit murder and treason in order to obtain it; and when death was not something to be feared but, on the contrary, very often to be embraced.

Perhaps the best example of the latter philosophy comes in the form of two followers of the official who will eventually hire Ogami to kill the rebel samurai. In an attempt to determine whether this paid assassin is indeed the notorious Ogami Ittō, the official orders the other two, both skilled swordsmen, to attack him, reasoning that if they can kill him, obviously he is not Ogami. On the other hand, if he kills them… “It is better if we are the ones to die!” enthuses one of the underlings, and needless to say, he gets his wish, in one of this film’s most blackly humorous moments: Ogami is attacked from behind by the two swordsmen while negotiating with the senior official, and kills them without even bothering to look around. He then resumes negotiations.

As Sword Of Vengeance unfolds, it becomes apparent that Ogami is a man who lives by an uncompromising and all-consuming code of honour. He must do so. Nothing else could make the commission of the kinds of deeds that he is ordered to carry out possible. His loyalty to the Shogun is unshakeable, even though it is clear to the audience that greed, hatred and paranoia, not justice, are behind many of the ordered executions. In fact Ogami occupies the impossible position of being an honourable man in a dishonourable service; something has to give.

The film’s first flashback shows us the last moments of Ogami’s normal life; and though it gives way soon enough to brutal violence, the quiet beginning of this sequence is critical for revealing to the audience the other side of Ogami: we see him as a considerate husband, a gentle and loving father. Questioned as to her evident distress, Ogami’s wife, Azami, confesses that the spirits of the dead are beginning to haunt her dreams.

Ogami does not respond directly to her implicit doubts about the righteousness of the recent wave of executions but, taking the baby Daigoro with him, retires to the shrine he has had constructed within the grounds of his estate, specifically for purpose of honouring the spirits of those he has executed. He is scrupulous in this duty, as in all other duties; and it is through his very meticulousness that his enemies strike at him.

While Ogami is conducting his religious ritual, his home is invaded by a band of assassins, who slaughter every member of his household; and it is while Ogami is cradling his dying wife that the invaders plant within the shrine a mortuary tablet marked with the sacred symbol of the Shogun upon it.

There it is “found” by Bizen, one of the Shogun’s “inspectors”—in essence, the police, although their duties extend to monitoring religious practices. Bizen’s first words imply that he believes Ogami himself is responsible for the slaughter of his own family; he goes on to produce a “declaration”, supposedly offered voluntarily by three samurai immediately before they committed seppuku at the gates of his, Bizen’s, house. The declaration accuses Ogami of plotting against the Shogun’s life: an accusation of which the mortuary tablet is considered proof.

Even in the midst of his grief and rage, Ogami sees clearly enough the plot against him; sees, too, the significance of Bizen’s men being armed and dressed in sword-mail. In a flash he understands both the plot and its intentions, that it is part of a larger scheme to give power into the hands of the so-called “Shadow Yagyū”, an offshoot of the main clan, who in particular desire the post of executioner. The Shadow Yagyū are led by a man called Retsudo—who happens to be Bizen’s grandfather…

Bizen is surprised and rather impressed by the depth of Ogami’s knowledge; so much so that he decides he must die immediately, instead of being arrested and tried by the Shogunate.

Of course—that’s easier said than done.

The first of Sword Of Vengeance‘s many explosions of violence follows as, in spite of being desperately outnumbered, Ogami literally carves his way through Bizen’s men, escaping onto a waterfall-bridge that fords the river. At last only Bizen himself remains. Ogami jumps down into the water, forcing Bizen to confront him on his own terms: a move that causes an elderly man watching from nearby to shake his head in dismayed anticipation.

This is the treacherous Retsudo, who has planned Ogami’s downfall—but can only look on as his followers pay with their lives attempting to implement only the first stage of the plot. Retsudo cannot withhold a certain admiration for Ogami, muttering to himself about his “Suiouryu” (Seagull) Technique. As Retsudo expects, the final encounter ends in Bizen’s bloody death…

Ogami then turns upon the old man, declaring his intention of destroying the Shadow Yagyū. Retsudo takes this coolly, pointing out the degree to which the Shogunate depends upon the Yagyū, and arguing that in the wake of the slaughter of Bizen and his men, which ended the bloodline of the true Yagyū, the Shogunate will sanction even the Shadow Yagyū. As for Ogami Ittō, he is a condemned traitor…

The first flashback ends here, and Sword Of Vengeance returns to Ogami pushing Daigoro’s cart through the pouring rain, until they enter a small village. Three samurai watch the two intently from cover. The leader of the three tells his subordinates that, two years earlier, the Shogun’s official executioner disappeared. Since then, strange tales have been heard of an assassin for hire, who travels the country with his small son; they are known as “Lone Wolf and Cub”. The samurai hesitate, however, wanting to be assured that the assassin is indeed Ogami Ittō, who defeated the best swordsmen of the Yagyū clan. The leader of the samurai proposes to his underlings a rather drastic test, by which they may find out for certain…

The question of Ogami’s identity having been settled via his hilariously casual dispatching of the unfortunate underlings, the surviving samurai identifies himself as the Edo Chamberlain of the Oyamada Sanmangoku Clan. He explains that there is a plot by a rival chamberlain to assassinate the Clan’s leader, Lord Noriyuki, and to install the head of a branch family as leader, by which means the chamberlain can control the clan. Noriyuki is in poor health, and will shortly be leaving Edo to travel to the country town of Gounomori, famed for its therapeutic hot-springs. Four ronin have been hired to assassinate Noriyuki: three expert swordsman and a “horse musketeer”, who uses pistols.

Accepting the assignment, Ogami sets out for Gounomori. The weather has cleared, and children are playing in the road, bouncing a ball while singing a rather rude song—the lyrics of which, the gleeful Daigoro immediately picks up and begins singing too. Ogami, however, is focused on the ball…

A second lengthy flashback reveals the events which set Ogami on his current path. Ordered by the Shogunate to commit seppuku, and to assist Daigoro to do likewise, so as to end the bloodline of the family, Ogami took the shocking decision to disobey: aware of the magnitude of the step, but also conscious of the Shogun’s own lack of faith in him—that he has sold out his most loyal follower for political expediency. Only by defying orders will Ogami have a chance to vindicate his honour.

When the Shogun’s men arrive with the official order of condemnation, they are gratified to find Ogami and Daigoro already clad in their white death robes—but there’s a little surprise in store for them… The horrified officials call upon their armed followers, ordering them frantically to kill Ogami. They try, but fare no better than did Bizen and his fellow Yagyū.

Ogami and Daigoro make it safely out of the gates of their home, but there find waiting for them representatives of the newly-established Shadow Yagyū. They are led by Retsudo, and inform Ogami that they now hold the post of executioner: they even offer to help him commit seppuku.

In response, Ogami throws back his death robes, revealing beneath them his own executioner’s robes which bear the sacred symbol of the Shogun. This is something even the Shadow Yagyū dare not take action against (at least, not so publicly). Instead, Retsudo is forced to offer Ogami a deal: if he will relinquish the robe and its protecting symbol, they will send against him their best swordsman in an honourable duel. If Ogami wins, he may live wherever he likes, outside of the Shogun’s domains.

Despite all the advantages being with the Yagyu representative, the duel is won by Ogami; and his enemies must allow him to set out into his exile…

And what of Daigoro? One of Sword Of Vengeance‘s most famous set-pieces finds Ogami setting before his infant son a sword and a ball, and compelling him to choose between them. If the boy chooses the sword, he will become an outcast like his father, to “tread the path of the assassin”; the ball, and he will be “sent to join his late mother”—by his father.

After what we have already witnessed in this film, we have no doubt that Ogami will kill the boy instantly should he choose the ball; and yet had this come to pass, it would not have been an act of brutality, or indifference, or evidence of a selfish desire not to be burdened with the child, but genuinely an act of love. This is perhaps the time when an understanding of the film’s attitude towards death becomes absolutely critical. Ogami hopes that his son will choose the ball, not because he does not love him, but because he honestly believes that the boy would be better off dead. His own chosen path is not what he wants for his son.

However, having made his child’s life or death a matter of destiny, when Daigoro chooses the sword, Ogami is compelled to abide by it. (“An assassin with a child,” he comments wryly, as he contemplates the future.) The two set out on their fateful journey, Daigoro in the wooden cart that bestows upon this set of films one of its many alternative titles—and which, as the series progresses, will prove to be considerably more than just a baby cart.

Sword Of Vengeance is not, by any stretch of the imagination, a film that encourages facetious thought, but I couldn’t help reflecting that Ogami’s situation represented one of the more interesting depictions of the eternal problem of juggling parenthood with a career—and of course, of single parenthood.

The relationship between Ogami and his son is one of the film’s most fascinating aspects, and is all the more so for, in a sense, being told backwards. As indicated, we first see Ogami executing the infant Lord Hirotada; our next view of him is out on the road, carrying a banner that, among other things, offers to rent out his own child. Neither of these things exactly encourages the audience to take a sympathetic view of Ogami, and nor does his habitually grim expression; but as the story progresses, we slowly come to an understanding of the sincere love that exists between the Lone Wolf and his Cub.

Ironically enough, one of the most startling touches in the entire film comes when we are permitted a glimpse of the father and son bathing together in the hot-springs, where we find Ogami gently splashing the giggling child with water, and smiling. In the overall context of the film, this moment of playfulness is so unexpected as to be almost shocking; and indeed, it is no more than a moment. Almost immediately, Ogami’s mask slams back into place—because, it seems, he has noticed that we are watching him, but in reality because someone else has entered the spa. Brief as it is, however, this scene allows us a much greater understanding of our anti-hero. Far from being a mere killing machine, he is a man of deep emotion, no matter how vice-like the hold he ordinarily keeps upon himself.

And Ogami will need every bit of his self-control to deal with the situation he finds waiting for him in Gounomori. The town has been taken over by bandits—hired by the four ronin whom Ogami has been sent to kill, we later learn—and while they wait for their masters, these men amuse themselves by terrorising the townspeople and the visitors to the spa. Met at the suspension-bridge that is the only way into town, Ogami takes in the situation at a glance, meekly surrendering his sword, and convincing the bandits that he is just another visitor (“Would I bring a child here otherwise?” he argues). His only abrupt movement occurs when the bandit’s quest for amusement takes the form of literally raping a young woman to death in front of her elderly father (easily the film’s most disturbing aspect, in spite of all the bloody sword-play). Ogami does not intervene, but steps swiftly in front of Daigoro’s cart, shielding the boy from the dreadful scene taking place taking place literally in the middle of the road.

“Fatherly love?” jeers one of the bandits, and of course he’s right; but we cannot help but notice the moral ambiguity associated with Ogami’s protection of Daigoro here, since he never tries to shield him from his own sword-play—and, furthermore, sometimes goes so far as to use the boy as weapon, as we have already seen.

But the bandits as such are not Ogami’s business; his target is the four ronin who hired them, his business to survive until they appear on the scene; and so, apart from this one impulsive act, he remains completely passive, allowing himself and Daigoro to be rounded up with the other captured visitors, and making no response to the taunts and insults rained upon him: a stance interpreted as pusillanimity by the bandits and his fellow-captives alike.

One person, however, sees further.

One of the overwhelming impressions left by Sword Of Vengeance is that the Tokugawa Shogunate was not a good time to be a woman. We meet only five women in the course of the story. The first is Azami, whose position of privilege leads only to her death, as she is murdered by the Shadow Yagyū. On the road, we see a young townswoman, driven insane by betrayal and the death of her child, and her elderly mother, who has the thankless task of trying to care for her unbalanced daughter. Meanwhile, the bandits carry out their rape-murder as publicly as possible, while treating it as nothing more than a joke.

The fifth woman is Osen, a prostitute, who is introduced penned up with the visitors to Gounomori (who, we gather, she usually earns her living by servicing). The captive samurai, bitterly ashamed of their inability (or unwillingness) to combat the bandits, vent their frustration upon Ogami, making him the subject of constant derision and abuse. Paradoxically, it is only the prostitute who can recognise the qualities that mark the former Shogunate executioner, and who understands almost instinctively that Ogami’s façade of cowardice is exactly that. Osen has, as she herself later puts it, “Known a lot of men”; her experience grants her an insight that will play its part in the ultimate defeat of the bandits and their masters.

Already we have seen that the girl, a social outcast of the most despised kind, has been the only one with backbone enough to stand up to the bandits, even if only verbally. When the bandits, frustrated by Ogami’s lack of response to their insults, make a move to provoke action from him by threatening Daigoro, Osen instantly intervenes, cleverly deflecting attention back to Ogami himself with a sneering speech about his timidity. Finally, however, Osen pushes her luck too far: the bandits decide to punish the two rebels, and amuse themselves, by forcing Ogami to have public sex with her. The horrified girl cringes, hesitates—and then the decision is taken out of her hands by Ogami, who without a word begins to disrobe.

What follows is one of the strangest and most beautiful scenes in the whole film, as what was intended as punishment, as public humiliation for both Ogami and Osen, is transformed by camerawork and editing into a most tender and intimate encounter. Of course, Ogami’s willing self-degradation is interpreted by the other captives as still further evidence of his spinelessness, but Osen knows better: sensing that she was on the verge of suicide (she was trying to work up the courage to bite off her own tongue, she later reveals), Ogami acted not to save himself, but her. “A samurai sacrifice his pride for a woman like me!” she moans, in full and painful consciousness of the magnitude of Ogami’s gesture.

The consequence is inevitable. When Sword Of Vengeance reaches its conclusion, it is with a scene like many seen in American movies over the years: the “fallen woman” gazing helplessly, longingly, after the hero as he walks away from her, accepting that she is morally unfit for him despite her courage and her love for him. Yet here Osen is not rejected because she is not “good enough” for Ogami, but simply because the Lone Wolf and his Cub must make their own way along the bloody path that they have chosen, alone.

But before that happens, there must naturally be the showdown between Ogami and the four ronin he has been hired to kill—and retribution for the bandits.

Paving the way for the planned assassination of the Lord Noriyuki and his followers, the ronin decide to kill all the captive samurai to keep them from talking, and as a warning to the terrified townspeople (who to this point have been confined to their homes). One of the captives obligingly kneels down to commit seppuku, but demands a “decapitator” to help him. The elderly leader of the bandits has been convinced all along that he has seen Ogami somewhere before, and at this, the penny drops, and with a vengeance: he realises exactly who the “coward” in their midst is…

But by then it is too late; Ogami is already making his move. At this point we learn that Daigoro’s cart is much more than it appears: from it Ogami produces weapon after weapon, mowing down his enemies in an orgy of bloodletting. Osen here again displays her courage, swooping in to snatch up Daigoro and carry him to safety—and thus allowing Ogami to use the metal-plated cart to shield himself from one of the ronin who, as was warned, is an expert with pistols—but only single-shot pistols. (Anyone who brings guns to a sword-fight deserves what he gets…which in this case is a split skull.)

Ronin and bandits alike fall under Ogami’s sword, until every one of them lies dead and the captives are freed. Not that Ogami cares much for that; he has fulfilled his commission and earned his pay, and it is time for him to move on…

The “Lone Wolf and Cub” films are famous, not to say notorious, for the extremity of their fight scenes. At times it seems as if the films exist only to demonstrate how many different ways you can kill someone with a sword. When Ogami goes into action, it is at all times to kill, and preferably with one blow. Heads roll, limbs are lopped off and, in one memorable instance, a pair of feet remain standing while their owner lies beside them, screaming in agony. Arteries are severed, and blood erupts from the wounds in literal geysers.

Yet for all that, there is an undeniable beauty to much of what we see, even to the scenes of violence. Appropriately, given the film’s origins, the production design is very stylised; many scenes look exactly like frames of the manga from which they were derived.

(In keeping with this aesthetic, the “blood” is fairly obviously red paint, which does serve to take the queasiness factor down a notch or two.)

One of the most sumptuous of all the scenes in Sword Of Vengeance is the opening sequence of the execution of the boy Daimyo, which contains an absolutely stunning use of white on white on white. Other scenes, particularly those that take place out of doors, are simply breathtaking. This is perhaps most evident during Ogami’s duel against the representative of the Shadow Yagyū. The fight takes place at dawn, in a field full of long, swaying grass. As the two warriors face each other, Retsudo gloats mentally that Ogami must fall: the Yagyū swordsman has the sun at his back, while Ogami has Daigoro bundled up in a sling on his. But the executioner has an unexpected manoeuvre up his sleeve. The two men charge at each other, and at the last instant Ogami bends over. We see that Daigoro has a small mirror bound to his forehead. The reflected sunlight blinds the Yagyū swordsman for just an instant, and that is long enough for Ogami. There is almost a freeze-frame when the blow has been struck, one of quite unearthly beauty: the rising sun, the mountain in the background, the gently swaying grass, Ogami standing motionless with Daigoro on his back and his sword in his hand—and the decapitated body, still upright, gushing blood into the air…

Sword Of Vengeance carries an intense, pulsing score by Sakurai Hideaki, and while that is very effective, equally so is the film’s occasional use of silence, particularly at moments of death. Here, we are left listening to the wind in the grass; after an earlier battle, it was to the sound of a waterfall.

But truly, the film is an artistic triumph all around—if you have the stomach for it. The direction of Misumi Kenji, the cinematography of Makiura Chikashi, the art direction of Naitō Akira and, perhaps above all, the editing of Taniguchi Toshio combine in a manner that, while staying true to its source, make Sword Of Vengeance a powerful piece of cinema.

And while we cannot, overall, call this “an actor’s film”, there are two exceptions to that statement, exactly where we need them most. Tomikawa Akihiro, four years old at the time of filming but playing slightly younger, gives us a Daigoro who projects both a natural vulnerability and a sense of absolute trust in his father—and who is, besides, as cute as a basketful of kittens.

(Despite the rampant bloodshed here, I promise you that one of the images you’ll carry away from Sword Of Vengeance is Daigoro’s smile.)

But of course, this film is absolutely dominated—as it should be—by Wakayama Tomisaburō’s remarkable interpretation of Ogami Ittō. With his grim visage, growling voice and intimidating physical presence, Wakayama succeeds in making Ogami the larger-than-life figure these stories require, while at the same time offering a nuanced performance that allows us to glimpse the complex emotions and motivations that lie beneath the former executioner’s stoic demeanour. Though it seems that, in Japan at least, these films have been somewhat forgotten in the wake of the two television series that came later, the first running from 1973 – 1976, the second from 2002 – 2004, and starring Yorozuya Kinnosuke and Kitaoji Kinya, respectively, Wakayama Tomisaburō remains for me the definitive Lone Wolf.

Although I read many of the manga as a teenager (my parents not being close monitors of my reading material), I’ve hesitated to watch the movies based on them as I generally don’t get much out of the heavy gore that the battle setpieces rely on and it’s less jarring in black and white still images. But as I recall, you aren’t into blood and guts either, so this examination might change my mind! I think my tastes line up pretty well with yours, so perhaps we’ll see if I have the stomach for it sometime soon.

LikeLike

No, ordinarily I’m not. It’s all very stylised in these films, and therefore a bit easier to take. The screenshots indicate the kind of thing you’d be dealing with.

From memory the second film is much more (or more consistently) violent than the first, where the fights are alternated with the back-story. I’m interested to note, though, that this film was given an R-rating, whereas the second is only MA; I’d guess the rape scene was responsible for that.

LikeLike

Not into blood and guts? I didn’t recall that about you, unless eyes are involved.

And yet you reviewed all the Friday the 13th movies. That’s some dedication.

LikeLike

I prefer to be frightened rather than grossed out. That’s not to say I don’t watch gory films but they’re not my favourites.

As for the F13s, that’s just masochism. 🙂

LikeLike

Our rating system (I’m in the US) must be different from yours. Is MA Mature Audiences, and that’s lower than Restricted?

LikeLike

Yes, our rating system is more graduated than yours:

G – General audiences

PG – Parental guidance recommended

M – Mature (not recommended for under 15)

MA – Mature accompanied (no-one under 15 unless accompanied by an adult)

R – Restricted (no-one under 18)

So our M, MA and R put together would be your R rating, I guess. On this scale our R is more like your NC-17 (do you have that any more?), but there’s no stigma attached.

LikeLike

That’s about the same as our present rating system: M = PG13, MA = R, R = NC17.

To confuse things, the American system used to have an M rating, a few years before this movie came out.

LikeLike

I guess the other difference is what the ratings boards tend to get fussed about: as I mentioned, I suspect the rape scene got Sword Of Vengeance its R, rather than the straight violence. I remember a story about the release of Being John Malkovich, which got an MA rather than an M because of the use of “c**t”; our raters don’t like that word.

Generally they’re not worried about nudity, though “high-level sex scenes” will get you an MA, and that plus “high-level violence” will probably get you an R.

The main area we get ratings arguments is superhero films, which the distributors always want M, of course, but where some of the violence tends to cop an MA.

LikeLike

Thanks for the breakdown. Ratings systems kind of fascinate me, especially since here in the states they are notoriously opaque (nobody knows who’s on the board or why they make the decisions they do). I think we still have NC-17, but usually films that would have gotten that choose to go with Unrated as I guess they get less of a hit at the box office for it. As you said, there’s still a stigma to it.

LikeLike

Sorry for the OT, but I just finished a novel you might like, Lyz. It is Tim Power’s latest _Medusa’s Web_. It is a time-travelling ghost story set in present day and 1920’s Hollywood. As usual, Power’s weaves history (the 1923 Salome film plays a prominent role) with his magical fantasy. It has a ghost cat in a bit part, too.

LikeLike

Not at all! Thank you for the recommendation—I need more ghost cats in my life… 🙂

LikeLike

I wonder whether one might usefully argue that this is one of the key differences between the wandering-Samurai movie and the wandering-gunfighter Western: the ronin has turned his back on his class and honour, at least in the eyes of the world, and that has to be explained; while the Man With No Name doesn’t really need an excuse at all. (And, again, the ronin can show his softer side, while the MWNN can’t.)

LikeLiked by 1 person

To my mind that makes the wandering samurai superior, but I suppose it puts restrictions on his behaviour that don’t apply to the MWNN, which may be preferable for others.

LikeLike