“Oh! Amon-Ra – Oh! God of gods! Death is but the doorway to new life— We live today; we shall live again— In many forms shall we return – Oh, mighty one.”

Director: Karl Freund

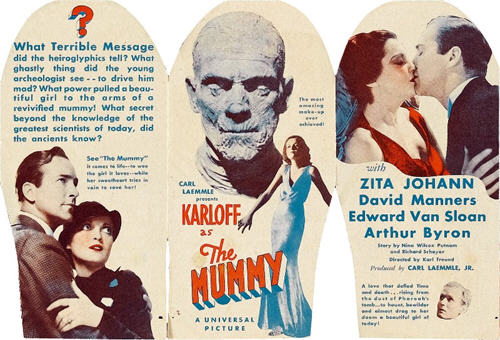

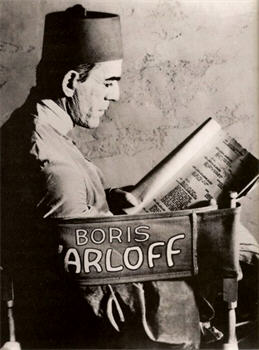

Starring: Boris Karloff, Zita Johann, David Manners, Edward Van Sloan, Arthur Byron, Noble Johnson, Kathryn Byron, Bramwell Fletcher, Leonard Mudie

Screenplay: John L. Balderston, based upon a story by Nina Wilcox Putnam and Richard Schayer

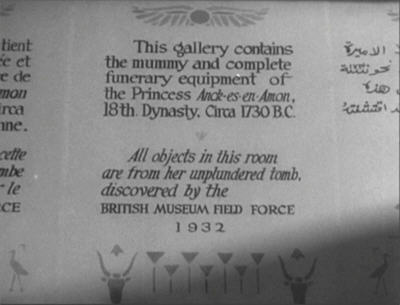

Synopsis: In Egypt, the members of the British Museum Field Expedition of 1921 examine and catalogue their recent finds. Ralph Norton (Bramwell Fletcher) is eager to inspect the team’s most exciting finds, the mummy of Imhotep, High Priest of the Temple Of The Sun at Karnak, and a sealed chest; but the director of the expedition, Sir Joseph Whemple (Arthur Byron), insists that everything be done in the usual orderly manner. Dr Muller (Edward Van Sloan), an academic with expertise in the Egyptian occult, then makes a startling discovery: the mummy did not undergo the usual embalming procedure. Moreover, the contortions of the body show that Imhotep was buried alive; while the spells usually engraved on a coffin to protect the soul on its journey to the Underworld have been chipped off. The men wonder grimly what crime could have deserved so dreadful a punishment, with Dr Muller suggesting sacrilege. Norton again tries to persuade Sir Joseph to examine the chest, and he finally agrees. Inside the chest is a smaller casket, and Sir Joseph translates the engraving upon it as a terrible curse. To Sir Joseph’s surprise, Muller reacts with fear, pleading with him to heed the warning. When Sir Joseph insists on going ahead, Muller takes him outside to talk, cautioning Norton to touch nothing. Muller tells Sir Joseph that the casket may contain the Scroll of Thoth, with which Isis raised Osiris from the dead, and adds darkly that many of the old spells are still potent. Sir Joseph replies that even if he believed the curse, he would go ahead in the name of science. Meanwhile, Norton allows his overwhelming curiosity to get the better of him, opening the casket and removing the parchment within. Unrolling it, he begins a translation, reading the words aloud—and behind him, unseen, the mummy of Imhotep stirs to life… Norton’s terrified screams, and then his hysterical laughter, bring the two men running. They find Norton hopelessly insane—and the mummy and scroll both gone… Ten years later, Frank Whemple (David Manners) is bringing his own depressingly unsuccessful dig to a conclusion when he and his partner, Professor Pearson (Leonard Mudie), receive a visit from a mysterious Egyptian who introduces himself as Ardath Bey (Boris Karloff). Bey brings an artifact, part of the funerary equipment of the Princess Anck-es-en-Amon, daughter of the Pharoah Amenophis, and tells the Englishmen that he believes her tomb to be only a hundred yards from their camp. Under Bey’s guidance a new excavation begins, and an undiscovered tomb is unearthed. Pearson insists upon summoning Sir Joseph Whemple, who has not set foot in Egypt since the tragic conclusion of his last expedition. The new finds, put on display in the Cairo Museum, cause an international sensation. Sir Joseph finds Ardath Bey with the mummy of Anck-es-en-Amon and gives him the freedom of the museum. Later that night, Bey returns to the display room where, by the light of a lamp, he unrolls a scroll and begins to read aloud… Meanwhile, in Cairo, Helen Grosvenor (Zita Johann), the half-Egyptian daughter of the English Governor of the Sudan, is suddenly entranced. Dazed and unknowing, she leaves the party she is attending with Dr Muller and heads for the museum, where she attempts unavailingly to get in. She is seen by Frank Whemple and his father as they are leaving, and Frank tries to intervene—only to have Helen collapse at his feet…

Comments: By the end of 1931, the fight to establish the horror movie in America had been fought and won. Although it was the gamble of Universal Studio’s twin nightmares, Dracula and Frankenstein, that had in effect created the horror genre, it was Paramount’s filming of Dr Jekyll And Mr Hyde that legitimised it, by demonstrating that the horror movie could also be art. Having sat back warily and watched as Universal in particular bore the brunt of the initial critical and social backlash, the other studios now jumped upon the bandwagon, determined to cut themselves a slice of this unexpected financial pie.

Within the next twelve months, MGM, RKO and Warners, through its partnership with First National Pictures, all joined the fray; and indeed, 1932 would ultimately prove to be one of the finest and richest years in the history of the horror movie. Curiously, after its hugely successful first venture, Paramount withdrew itself from the battle (although when the studio did finally produce another horror film, it would again be a work of extraordinary power and artistry). Universal, on the other hand, seeing its rivals harvesting the new cash crop it had developed, redoubled its efforts; and towards the end of the year made another kind of history by producing the first major horror movie with an original screenplay written directly for the screen.

While there were original screenplays written for horror movies throughout the silent era and in the early days of sound, these were without exception either examples of explained-away horror, as in most of the “old dark house” comedy-horrors, or of real-life grotesquery, as in the films of Lon Chaney. When it finally came to the genuinely supernatural, Hollywood looked to its libraries and its theatres. Horror movies were far from alone in their dependence upon literary sources, of course, but unlike other genres, here there was a secondary motive lurking behind the obvious one: it was a way of either sharing or, preferably, deflecting the blame. If you could trumpet in your opening credits that your horror movie was based upon “the classic tale” by Edgar Allan Poe or Robert Louis Stevenson or H.G. Wells, it was less likely that the critics would be quite so savage.

However, by the closing months of 1932, screen horror was firmly enough entrenched for Universal Studios to commission an original tale for its next production. It assigned to this task journalist and author – and creator of a series of illustrated comics for children – Nina Wilcox Putnam, who crafted a treatment based upon the true story of “Cagliostro”, an 18th century Italian charlatan who successfully passed himself off as an alchemist. Putnam’s story, however, made Cagliostro’s powers real, and told the tale of a man who had lived for centuries, finally to be brought undone by the memory of a tragic love of countless years before. This treatment, after undergoing further development by staff writer Richard Schayer, was finally handed to John L. Balderston, who discarded the true story aspect but retained the idea of an immortal, and ultimately deadly, love.

For better or for worse, John Balderston had, by this time, already played a critical role in the development of American horror, first re-writing Hamilton Deane’s stage version of Dracula, upon which the screen version would largely be based, and then performing the same function for Peggy Webling’s version of Frankenstein.

(I say “for better or worse” because historically imperative as these films are, the screenplays for both Dracula and Frankenstein are probably – certainly in the latter case – their weakest aspect.)

The story of the mummy did have some literary precedent – Sir Arthur Conan Doyle had dabbled, and so had Bram Stoker, and even Poe – and there had even been an earlier mummy film, of sorts: 1918’s Die Augen Der Mumie Ma, directed by Ernst Lubitsch, of all people, and starring Emil Jannings and Pola Negri; but John Balderston drew upon none of this in shaping his screenplay. He had no need to, his own experiences giving him all the inspiration he needed. A journalist before adopting a literary career, Balderston was working as the London-based correspondent for the New York World newspaper when he was assigned the task of covering of one of the most breathtaking stories in archaeological history, the discovery and opening of the tomb of Tutankhamun in November of 1922.

Due to the methods employed by Howard Carter and his team, it was almost ten years before their investigation of their finds was fully completed: an event that finally occurred in February of 1932. However, it was not only archaeological interest that kept the story of Tutankhamun in the public eye during the intervening years, but rather the so-called “Curse Of The Pharaohs”, held to strike down all those with the temerity to violate the tomb of a pharaoh. In the case of Tutankhamun, the story was fuelled by the deaths of the financer of the Carter dig, Lord Carnarvon, only five months after the discovery, and of railway magnate George Jay Gould a month later, after he paid a visit to the tomb. (Howard Carter himself would also die prematurely, of leukaemia, in 1939.)

The newspapers and the public had a field day with these sensational events, and of course were not in the least dissuaded from their belief in the curse – or their exploitation of the curse, as the case may be – by anything that might be said by sceptics and statisticians. So it was that a decade after the discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb, words like “mummy” and “tomb” and “Egyptology” were associated in most minds not with science or history, but with supernatural powers and unnatural death.

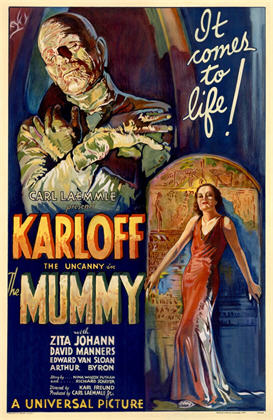

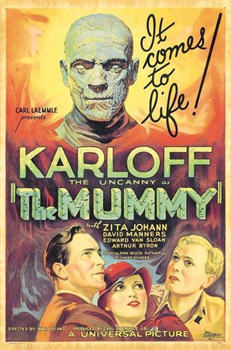

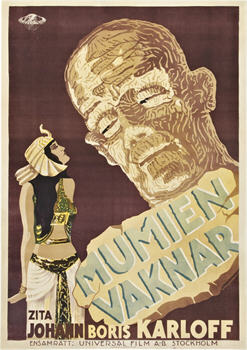

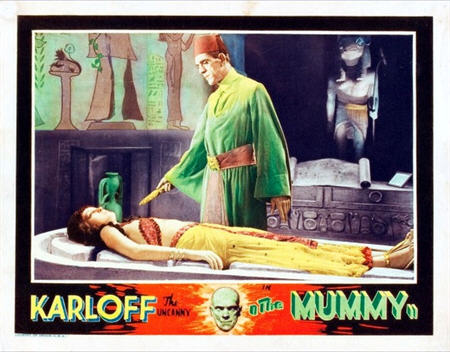

For John L. Balderston, this was an opportunity not to be missed. Combining his journalist experiences, his own life-long interest in ancient civilisations and his working knowledge of the horror story with the public’s desire for the sensational, Balderston scripted a tale that combined Egyptology and ancient curses with one of Universal Studio’s favourite horror movie themes, the battle between the ancient and modern worlds for possession of a soul; and which furthermore provided a perfect vehicle for America’s unlikely new king of horror, Boris Karloff—or, as he was billed here, “Karloff the Uncanny”.

After more than a decade of bit parts and supporting roles – interspersed with periods of manual labour such as road-building and ditch-digging, when times got particularly tough – Boris Karloff’s professional life changed utterly and irrevocably almost overnight, with the November 1931 release of Frankenstein; and at the age of forty-four, he found himself Hollywood’s most improbable superstar.

(So much so, he was awarded the ultimate honour of billing by surname alone, an acknowledgement at the time granted otherwise only to Greta Garbo.)

The roles got better after Frankenstein, although not immediately bigger – Karloff’s most memorable performance in this interim period was in Scarface – but horror continued to go from strength to strength as 1932 progressed; and by the end of the year, the studios were bidding for Karloff’s services for their movies. In rapid succession, he re-teamed with James Whale – and played another supporting, and non-speaking, role – in The Old Dark House; finally won stardom and a chance to put his remarkable and distinctive speaking voice to glorious use in MGM’s The Mask Of Fu Manchu; then returned to Universal to take the lead role in The Mummy, released thirteen months after his first screen triumph.

The most immediately striking thing about The Mummy is the confidence with which it plunges the viewer into the world of its story. It is evident at first glance how much effort was put into the production design of this film, with Universal demonstrating their commitment to the project by hiring the Hungarian artist, muralist and illustrator William Pogany to oversee the art direction of the film. The recreation of both ancient Egypt and “this dreadful modern Cairo”, as the film’s leading lady will shortly phrase it, is atmospheric and quite convincing.

(To evoke Egypt itself, the film-makers used a judicious mixture of stock footage, model work and location shooting, the latter carried out in Death Valley and in Red Rock Canyon, which would over time become one of the most famous of all science fiction locations, appearing in everything from Rocketship X-M to The Andromeda Strain to Jurassic Park.)

The film’s visuals are distinctive and beautiful, and show the guiding hand of Karl Freund, the German cinematographer, here sitting in the director’s chair for the first time in America…att least, officially: arguments continue over Freund’s possible involvement in the direction of Dracula.

After establishing shots of “Egypt”, and all those images with which by now the whole world was familiar, we move to the dig site of the British Museum Field Expedition, 1921—neatly recalling the Carter expedition without directly referencing it. At once we are within the workroom of Sir Joseph Whemple, head of the dig, and his young assistant Ralph Norton; a room cluttered with the debris of their profession. Sir Joseph and the impetuous Ralph are debating the best way to go about the investigation of their latest discoveries, with the more experienced man insisting upon order and method, as always, while his young assistant pleads for an immediate examination of two startling finds.

However, it is the third member of the party, the Austrian physician and expert upon the Egyptian occult, Dr Muller, who seizes our attention. As Whemple and Norton argue, Muller is busy examining one of the objects of their dispute: a mummy, and the sarcophagus in which it was buried.

We get a salutary reminder in this scene of just how far the horror film had come in just over a year and a half, of what distance the genre had travelled from the astonishing timidity of Dracula. That film had relentlessly undercut almost everything that might have the power to disturb the viewer, and kept every one of what should have been its gruesome highlights off-screen; this film plunges the audience directly into the grisly details of ancient Egyptian mummification, with Muller commenting, “The viscera have not been removed – the usual scar left by the embalmer’s knife is not there!”

This confirms Sir Joseph’s suspicions; that the occupier of the sarcophagus, Imhotep, died “in some sensationally unpleasant manner”; was buried alive, as the contortion of his muscles within the bandages indicates. Moreover, the sacred spells, intended to protect the soul on its journey to the Underworld, have been chipped off the sarcophagus, condemning Imhotep to eternal death in the next world, as well as this one. Sir Joseph suggests that Imhotep may have been guilty of an act of treason, but Dr Muller replies grimly, “Sacrilege.”

This mystery gives Ralph Norton an excuse to resume lobbying for the immediate examination of the second find, a wooden chest discovered with the sarcophagus. Accepting that he will get no peace otherwise, Sir Joseph agrees to the chest being opened. Eagerly, Muller and Ralph remove the rotting wooden lid, and strip the bindings from the object within, a smaller chest. Inside that again is yet another object, an ornamental casket. Sir Joseph leans close to translate the hieroglyphs carved upon it: “Death – eternal punishment – for anyone who opens this casket. In the name of Amon-Ra…”

(By the way, although modern viewers will probably wince and groan their way through the crude disembowelling of the wooden chest by Whemple and Norton – and although the scientist in me cannot let this scene go without a pained cry of, “Please, someone, put some gloves on!” – this depiction of the archaeologists’ approach to their work is not at all inaccurate. Incredibly, at the time little care was taken with objects considered comparatively unimportant, and sometimes even with important finds. In fact, in order completely to remove the golden artefacts with which Tutankhamun’s mummy was swathed, Howard Carter had it cut into pieces; an act which – among other things – significantly interfered with subsequent efforts to determine the young ruler’s cause of death.)

Ralph Norton moves eagerly to open the casket, only for Dr Muller to intervene, trying to dissuade the archaeologists from what he believes to be a dangerous and foolhardy act. The writing in this section of the film is particularly nice in its balance, allowing the three distinct points of view to emerge: the young archaeologist’s dismissal of the curse as “mumbo-jumbo”, the occult expert’s genuine fear, and the senior archaeologist’s insistence that even if he did believe, he would go ahead anyway, in the name of science. At last, Dr Muller, rather disgusted with the callow Ralph, persuades Whemple to step outside with him to continue their debate. As the two older men move away, Muller turns back to Ralph with a warning gesture: “Do – not – touch that casket.”

Out in the desert, Muller tries again to convince Whemple that the curse may indeed be a reality; and it is in this conversation that we learn the contents of the casket, with the two men in agreement that it holds the Scroll of Thoth, the sacred document with which Isis raised Osiris from the dead. Muller does his best, but Whemple is unmoved—although in what he intends as a gesture of reconciliation, he does invite Muller back inside, to help him examine the find. Muller refuses to be present at what he describes as “an act of sacrilege”, and prepares to leave. He does not get very far, however. Inside, Ralph Norton has allowed his curiosity to get the better of him…

After his sufferings on the set of Frankenstein, Boris Karloff was put through the wringer again for The Mummy, enduring a solid eight hours of makeup artist Jack Pierce’s ministrations in order to create the bandaged figure that we know so well even to this day.

(Clearly, the combination of Karloff’s uncomplaining nature and Pierce’s single-mindedness was a deadly one—or at the very least, painful in ways that hardly bear contemplating. “Jack did a great job,” Boris commented later with his usual rueful good humour, “except that he forgot to put in a fly…”)

So iconic is the image of Karloff as the mummy, so completely does it dominate all advertising art for this film (including the poster that, in 1997, sold for US$453,000), that it is always a shock upon repeat viewings to realise that this marvellous example of Jack Pierce’s art is glimpsed in only a very few brief scenes in the film itself. History has changed the way we view this aspect of The Mummy: almost every later mummy film features a bandage-swathed, ambulatory, murderous monster, and so, retroactively, we expect to see one here, too. That we do not may disappoint and frustrate some viewers, particularly those weaned upon today’s rub-your-face-in-it horror movies, but this restraint is the very essence of The Mummy’s most unforgettable sequence.

We have been aware of the bandaged figure of Imhotep all throughout the opening scenes, seeing it as the subject of Dr Muller and Ralph Norton’s examination; and then in the background as the three men debate the opening of the casket; as it is while Ralph Norton attempts, with little success, to concentrate his mind upon the translation of some tablets, the task that Sir Joseph has left him. At first Ralph tries to control himself, merely examining the outside of the casket; but finally his curiosity overwhelms his judgement, and he lifts the casket’s lid. Inside, as Sir Joseph and Dr Muller have anticipated, is an ancient parchment, the Scroll of Thoth. Ralph removes it from the casket and unrolls it, beginning a translation—and muttering the words aloud…

We see—well, what do we see? Not what Ralph sees. The glimmer of an eye, the movement of an arm; a hand, bandaged and crumbling, clutching at the scroll; a trailing bandage…and Ralph Norton, as he recoils from the impossibility before him and splits the night with a nightmarish scream—and then begins to laugh.

By the time Sir Joseph and Dr Muller re-enter the room, Ralph is beyond their reach. “He went for a little walk,” he gibbers. “You should have seen his face…” And he begins to laugh again, the laughter of the utterly, irretrievably insane. This is the last we see of Ralph Norton, but not the last we hear of him. A chilling epitaph is delivered a little later in the film, as two other archaeologists reflect upon his fate. “He was laughing when they found him,” muses one. “He died laughing—in a straitjacket…”

Instantaneous insanity is one of the most cherished tropes of horror film and literature – particularly if we extend our definition of “horror” to include various Gothic tales and melodramas – and I have encountered it more times, and in more formats, than I could begin to remember; but this brilliant, subtle sequence in The Mummy is the only instance of it I can think of where I honestly believe it: that a man could indeed encounter something so far beyond the normal parameters of human comprehension that, in a single instant, his mind could snap.

The Mummy now jumps forward over a decade, to a period contemporary with the film’s production, and to another archaeological dig—although one considerably less memorable than its predecessor. In fact, the British Museum’s Field Expedition of 1932, under the co-leadership of Sir Joseph Whemple’s son, Frank, and a Professor Pearson, has been a complete bust, yielding nothing more than “a few beads, a few broken pots”. The dig has already been broken up; Pearson and Whemple have stayed behind to close down the camp. Pearson in particular is disgusted and embarrassed by the poor outcome of their efforts, muttering in frustration over the fact that hard work is not enough: in archaeology, you need luck, as well, as Frank’s father always had…only Sir Joseph has not returned to Egypt since the disastrous conclusion to the 1921 expedition.

As Frank and Pearson reflect upon this, the door of their office swings open to reveal a tall, gaunt figure with strangely piercing eyes. He introduces himself as Ardath Bey, an Egyptian scholar, and he offers the two archaeologists a rich prize: a relic from the tomb of Anck-es-en-Amon, daughter of the Pharaoh Amenophis, a vestal virgin of the Temple Of The Sun, dedicated to Isis. This tomb, claims Ardath Bey, is only a hundred yards from the expedition’s campsite…

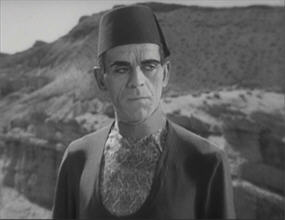

And so Boris Karloff in truth enters The Mummy, carrying but not hidden by the film’s second wonderful example of Jack Pierce’s artistry, the layer upon layer of wrinkles and dust that indeed give an impression of living parchment. It is beneath the makeup, however, that the power of this film is to be found. Karloff’s work in this film is remarkable—and as different from his contribution in Frankenstein as you can imagine. As the Creature, although it was finally driven to fury and violence, what we remember is the hapless innocence, the heart and gentleness of Karloff himself shining from behind the prosthetics.

Jack Pierce learned well this fundamental lesson, and again his makeup design for Ardath Bey allows Karloff’s own amazingly distinct and expressive features to show themselves, but with altogether different results. Karloff’s performance here is one of extraordinary stillness; his movements are minimal and deliberate; and yet his Ardath Bey radiates malevolence. From our very first glimpse of him, the impression is of something unnatural, and deadly.

The archaeologists are suspicious, but willing enough to take advantage of Ardath Bey’s seeming generosity; and sure enough, the tomb of Anck-es-en-Amon is found at the point to which he directs them. As Frank and Pearson stand before the unbroken seals of the tomb, untouched for 3,700 years, Pearson insists upon cabling England and sending for Sir Joseph.

There is a curious thing about many of the horror films of this era, namely that even after they began to be produced from original screenplays, a great many of them continued to be set in England or in Europe, and to feature people speaking very English English, whether the characters were or not. This habit of thinking in non-American terms, inculcated during the early days of screen horror in America, which drew so heavily upon the European literary tradition, would be a hard one to break for many screenwriters.

(It would – naturally – be Warners who would best succeed in creating genuinely home-grown horrors, although those films are a tale unto themselves.)

Of course, with The Mummy this Britishness is understandable and indeed unavoidable, since the story draws so openly upon recent English history. This, however, has another consequence—one which has shifted considerably in the intervening decades. There is an assumption made within this film that the audience will sympathise with the concerns and attitudes of its central characters, and in 1932, perhaps it did; but these days, it is more probable that the viewer will find the characters’ inherent prejudices and superior airs rather hard to swallow, to the point of taking a Schadenfreude-ish pleasure in their troubles.

The tone, indeed, is set as Ardath Bey approaches the field camp. Frank Whemple spots him, and reports the arrival of a visitor to Pearson, who inquires, “Colour? Nationality?” Shortly afterwards, we are introduced to our story’s heroine, Helen Grosvenor, who we are told is half-Egyptian on her mother’s side, while her father is the governor of the Sudan. “English, of course!” our informant adds hastily. Later, it will turn out that Sir Joseph Whemple’s own Nubian servant has gone over to the enemy, working for Ardath Bey from within Sir Joseph’s house. Dr Muller, discovering this, makes sneering reference to, “The ancient blood!”

But the attitudinal highlight is reached after the excavation of Anck-es-en-Amon’s tomb, when Frank Whemple, having already voiced his resentment over Ardath Bey being the one to locate the tomb, has a fit of the sulks over the fact that these Egyptian artefacts, discovered in Egypt via Egyptian knowledge and by Egyptian labour, have been put in display in – gasp! – Egypt! “I think it’s a dirty trick!” he huffs to his father. Indeed, the only thing likely to elicit a louder guffaw from the viewer is Sir Joseph’s response: “The British Museum works for science, not for loot!”

Actually, there is some balance here, thanks to Boris. When Ardath Bey makes his offer to Frank and Pearson, they not unnaturally ask why he’s telling them? “We Egyptians are not permitted to dig up our ancient dead,” comes the reply, carrying with it the sting of faint contempt. “Only…foreign museums.” Later, Ardath Bey evinces a profound dislike of being touched. We have already seen enough of him to know why that is, but Bey himself has another explanation: “An eastern prejudice,” he tells Sir Joseph—thus neatly playing upon western prejudices.

Ardath Bey is found by Sir Joseph within the gallery of the Cairo Museum, gazing longingly at the mummy of Anck-es-en-Amon. From here we get a whip-pan through the city of Cairo, to the balcony of a hotel where sits Helen Grosvenor, a hint of sadness in her expression.

Helen is played by Zita Johann, a stage actress appearing here in only her third film. Making The Mummy was not a happy experience for Johann. This was partly her own fault: although she was unable to resist the monetary lure of Hollywood, she retained a healthy contempt for the process of movie-making, and showed it a little too clearly. The main consequence of this was an instant and bitter falling out with Karl Freund, who went out of his way to make Johann’s on-set experience a difficult one. Fortunately, none of this shows on film. Cast primarily for her exotic looks (she was Romanian), Johann is an attractive and effective presence in The Mummy, and a very welcome change from all the blonde sylphs that populate too many of the films of this era.

(“This” era?)

Of course, at this historical distance we guess instantly the connection between Ardeth Bey and Helen Grosvenor. However inadvertently, The Mummy would bestow a very terrible legacy upon the genre film. Helen, as we correctly surmise, is the reincarnation of Anck-es-en-Amon, Imhotep’s lost love, for whom he died in that “sensationally unpleasant manner” all those centuries ago. In The Mummy, this storyline works wonderfully because it is absolutely integral to the film, its very heart and soul; but for decades afterwards, the reincarnation of an ancient love would become the prop of choice for far too many lazy screenwriters, unable to create a convincing relationship between two characters who are nevertheless supposed to be “in love”, or to think up another kind of link between the heroine and the bad guy, and with a random reference to Egypt tossed in by way of explaining yet another re-hash of this now tiresome cliché; so that these days, the mere use of the word “Egypt” in a horror film is enough to set the knowledgeable viewer shuddering in anticipation.

That night, Ardeth Bey returns to the display gallery. Kneeling by Anck-es-en-Amon’s mummy, and by the light of a lamp, he unfurls the Scroll of Thoth and begins to read aloud. This has no effect upon the swathed figure before him, but in Cairo, Helen Grosvenor is suddenly gripped by an irresistible force. As if in a trance, she leaves the party she was attending with Dr Muller, her host in Egypt, and makes her way to the Cairo Museum, where she attempts unavailingly to enter by the locked front doors. It is there that Frank Whemple first sees her, as he and his father are departing for the night. He approaches her—only to have her collapse at his feet.

Frank and Sir Joseph take her back to their hotel, where in her delirium she utters the name Imhotep…as well as speaking, as the startled Sir Joseph realises, in ancient Egyptian. Meanwhile, Dr Muller has tracked Helen to the museum, and from there to the Whemples’, and now arrives to find an embarrassed and bewildered Helen trying to make sense of what the overly-attentive Frank is telling her.

While it is true that The Mummy is an original work, viewers conversant with the horror films of this period will by this time probably be experiencing a certain sense of déjà vu. At its bare bones, there is a distinct resemblance between this film and Dracula, with a desperate struggle taking place for possession of a young woman’s soul, between an ancient, supernatural being on one hand, and the woman’s new love and the elderly savant assisting him on the other. The resemblance is only strengthened by Universal’s repeat casting, with David Manners returning as the love interest, and Edward Van Sloan doing duty as the film’s Van Helsing figure; while certain crucial touches from the earlier film, such as a sacred symbol as a form of protection and an emphasis upon the eyes of the undead antagonist, are carried over with little disguise or pretence.

Whether this carbon-copying is an example of Hollywood’s instinctive return to a successful well; whether John L. Balderston – a first-time screenwriter, after all – nervously retreated to what had worked for him in the past; or whether, conversely, Balderston saw an opportunity to correct what he felt was wrong with his earlier effort, is impossible to say. However, the reproduced details actually work better here, where the central triangle is far more successfully integrated into the story (in Dracula, it is never really clear why the vampire is so obsessed with Mina), and where the screenplay is better structured overall. It is evident that John Balderston was far more personally invested in this project, than he was when he took on the task of trying to “rescue” the stage version of Dracula.

Another thing that it is difficult to decide, particularly at this distance, is how far we are supposed to sympathise with Imhotep. It is certainly hard not to feel some connection with his quest—and indeed, only the most determined cynic could entirely resist the impossible romanticism of a love reaching across the centuries. These days, of course, the issue is muddied by our enduring affection for Boris Karloff; even when his characters are at their most evil, it is difficult not to be at least sneakingly on their side.

In The Mummy, this situation is exacerbated still further by the nature of the opposition offered to Ardath Bey / Imhotep. Boris Karloff may have suffered physically for his art at period, but it is doubtful whether anyone suffered artistically more than poor David Manners, who spent his time in film after film trying to make something of the dreariest, wettest excuses for “romantic leads” you could imagine. Manners himself was just as disgusted as anyone else about this, and as a consequence quit acting altogether only a few years afterwards.

(For a better David Manners role, I recommend The Death Kiss, in which he stars as a screenwriter turned amateur sleuth, trying to solve the murder of an actor that occurs, not just mid-production, but on camera. The film – inevitably, it seems – co-stars Bela Lugosi and Edward Van Sloan.)

The character of Frank Whemple is particularly problematic in this respect, because he is not just a drip, but often actively unlikeable. Even our first impression of him at the dig site is unfavourable, as we get the sense of a rather characterless young man who has followed in his father’s footsteps chiefly because he hasn’t the energy or the imagination to think of anything else. We certainly get no feel of any passion in him for what he does, even allowing for the failure of the current dig. Actually, it comes as no surprise to any follower of thirties horror to learn that the 1932 Field Expedition is a bust, not once we see who is charge of it!

It is supposed to be Helen’s growing love for Frank that ultimately protects her from Imhotep’s attempt to claim her soul, and we just don’t believe in that love. (Evidently no-one did: the screenplay has to tell us that Helen is falling in love.) Helen, in fact, ends up as the focus of what just might be the creepiest love triangle ever put on film. On one hand we have her centuries-old undead lover, who wants to kill her in order to make her immortal like himself; on the other, we have a young man who makes it clear that his immediate attraction to Helen is due to her resemblance to the dead body he has been researching.

Frank’s description of his interaction with the mummy, his unwrapping of her body, the inventory of the tomb – “But when we came to handle all her clothes, her jewels and her toilet things…” – is so obtusely crass, it is hard to know whether it is Anck-es-en-Amon or just Helen who recoils from it in distaste. “How could you?” demands his auditor, whoever she may be, leading to what is – for me, at any rate – the most wince-inducing moment of the entire film. “Had to!” replies Frank, looking puzzled at her reaction. “Science, you know!”

We are supposed to believe that Helen is finally won over by the simplicity and guilelessness of Frank’s all but instant declaration of love for her, but in the end it is her not-quite-joking inquiry – “Do you have to open graves to find girls to fall in love with?” – that tends to linger.

Meanwhile, the dead body of a museum guard has been found – dead of shock, is the diagnosis – and by its side, a roll of ancient parchment. With horror, Sir Joseph and Dr Muller begin to join all the dots, with Muller forcing the impossible truth upon his colleague: “Do you still think that the mummy was stolen?”

Ardath Bey – Imhotep, rather – shows up soon enough, seeking the scroll he was forced to leave behind at the museum. Instead he finds Helen. The two gaze intently at one another, holding a trivial conversation about the whereabouts of the men even as their eyes and their attitudes to one another say a thousand other things. (How much easier it is to believe in the instant connection between Helen and Ardath Bey, than it is in that between Helen and Frank!) With this scene, our literally eternal triangle is put firmly in place.

The Mummy shifts gears at this point, as the mystery aspect of its story is essentially resolved, and it becomes instead a question of Helen’s fate. Although Muller and Whemple now know the truth, it remains very unclear what they can do in the face of this powerful undead adversary. The tale’s fundamental resemblance to Dracula shows itself again here, as Muller confronts Ardath Bey with their knowledge of his true identity, and tries to trap him into betraying himself. Bey is forced to retreat without the scroll at this point, but Muller knows that it is only a matter of time, and tries to persuade Whemple to destroy the parchment. Although the archaeologist is reluctant, he finally accepts the necessity—but it is too late.

We get our first glimpse of one of this film’s most memorable touches here, the magic pool via which Imhotep is able to watch, and take action against, his enemies. As Sir Joseph places the scroll in his fireplace, Imhotep reaches out, chanting—and Sir Joseph collapses, clutching his chest in agony. The Nubian servant enters in the wake of his master’s death, retrieving the scroll and burning in its place some newspapers, which briefly serves to convince the others that Sir Joseph succeeded in destroying the ancient parchment before his death. Muller learns his mistake soon enough, however, and forces upon Frank a symbol of Isis, warning him that it is he, and not Helen, who is truly in danger.

Helen, meanwhile, has obeyed another distant call from her undead lover, and made her way to Ardath Bey’s house. There, he draws her to the pool, and shows her—herself, Anck-es-en-Amon, 3,700 years ago, when she died. “You will not remember what I show you now,” murmurs Ardath Bey, “and yet I shall awaken within you memories of love – and crime – and death…”

By 1932, the transition from silent to sound cinema was complete; motion pictures had adjusted to the change and developed an entirely new rhythm, reflective of the demands now made upon this mode of story-telling. It is one of The Mummy’s cleverest touches that the slice of ancient history to which we are now treated is shot in the style of a silent film; an art-form anachronistic even after so brief a passage of time.

We are witness to the death of Anck-es-en-Amon; to the anguish of her lover, Imhotep, High Priest of the Temple Of The Sun at Karnak; and to the desperation that drives him to an act of sacrilege: breaking into the Sanctuary of Isis and stealing the Scroll of Thoth; drawing upon himself the wrath of Isis herself, as her statue moves to point at him accusingly.

Retribution is swift. Imhotep is caught in the middle of his attempt to raise Anck-es-en-Amon – his choice of words highlighting the necrophilial feel of this whole film: “They caught me doing an unholy thing….” – and condemned to “the nameless death”. Again, The Mummy refuses to shy away from the visceral horror of its story, and we are witness to Imhotep’s living interment, his futile struggle, his wide, terror-stricken eyes, as the bandages are wound remorselessly about him…

(And since I’ve confessed so much to all of you over the years, I’ll confess this, too: I have a deep-rooted fear of suffocation, and this scene gives me the screaming horrors.)

“Anck-es-en-Amon. My love has lasted longer than the temples of our gods. No man ever suffered as I did for you…”

You would have to be dead yourself not to respond to this appeal on some level; and of course, there always is something irresistibly attractive in the notion of an undying passion – up to a point – and that point is, when the object of an obsessive love ceases to have any say in the matter. This is the stage we have now reached, wherein Anck-es-en-Amon is to have her resurrection whether she wants it or not, in payment for Imhotep’s unspeakable suffering. Then, too, Frank must be killed, because Helen’s growing love for him might bind Anck-es-en-Amon to her current form and her current life. There is no regret or hesitation in Imhotep’s manner as he makes these decrees; there is no longer the capacity within him for any emotion not connected directly with his own desires.

When Helen returns to the hotel, she is first cold to Frank, then desperate for his help, as the two different personalities begin to war within her: she speaks brokenly of, “Life within me, for something that isn’t me.” Helen grows ill, and a battle begins which, again, is too reminiscent of the struggle for Mina’s soul in Dracula, particularly in respect to Helen’s knowing conversations with Dr Muller; a repetition only hammered home by the repeat casting of Edward Van Sloan. As was Mina, Helen is secreted away by her undead lover. A near fatal attack upon Frank accompanies this moment, but he is saved by the symbol of Isis. Muller finds him lying unconscious outside of Helen’s room, but Helen herself is long gone…

So begins the final struggle, with Anck-es-en-Amon in control of Helen, speaking confusedly of “My father’s palace” and recalling her forbidden love for Imhotep. She mistakenly assumes, however, that the gods have forgiven them, and Imhotep must teach her otherwise, taking her into the gallery to show her—her own sarcophagus, her own dead body. Assuring her that although he could raise it, it would be no more than an empty shell, as her soul is elsewhere, Imhotep destroys Anck-es-en-Amon’s mummy by burning it—and then calls upon her to repay his love of centuries by giving him her life; by allowing him to kill her, so that she may be brought back, immortal, even as he was.

She follows him into the next room, but is sickened and terrified, first by her sight of the Nubian preparing for the rites of embalming, and then, fatally, by Imhotep’s touch, which leaves the dead dust of the ages upon her warm and living flesh.

As Anck-es-en-Amon retreats from Imhotep, Helen’s personality begins to reassert itself; and even as Helen had struggled with Anck-es-en-Amon, battling for life within her, now Anck-es-en-Amon feels Helen’s own fight for life. “I loved you once—but now you belong with the dead!” she tells Imhotep, but he is in no mood for rejection.

“For thy sake I was buried alive!” he thunders, trying to persuade her that “a moment’s agony” will be repaid with an eternity of love. But the sight of the bath of natron and the sacrificial knife are too much for Anck-es-en-Amon, who with a cry of terror tries to flee the room. Imhotep is too powerful for her, however, and when he wills her to return and submit, she must obey.

And then something truly remarkable happens. We have seen Muller reviving Frank, and having a sudden revelation of Imhotep’s plans for Helen. Everything we know of film-making, everything we have seen to date, and everything we will see for decades afterwards, leads us to expect a last second rescue of the helpless heroine by her lover—but it doesn’t happen quite like that. The Mummy instead gives us something rather more interesting.

As Imhotep approaches the altar upon which Anck-es-en-Amon lies, the sacrificial knife in his hand, he is stopped by the sound of Frank calling for Helen. This rouses the girl, who leaps from the altar, casting herself at the base of a statue of Isis, to whom she prays for forgiveness and protection. Frank and Muller charge in at this moment, but are frozen in their tracks by the power of Imhotep and unable to help.

But Anck-es-en-Amon’s prayers have not gone unheeded. Even as Imhotep turns to carry out his bloody deed, Isis, who we saw earlier react in outrage and accusation to Imhotep’s act of sacrilege, responds to the girl’s desperate plea, raising her ankh and destroying the Scroll of Thoth with a bolt of sacred fire—and causing Imhotep to crumble away to dust. Our final image is, granted, Helen – Helen – in the arms of Frank; but it is not that which we remember, but rather the unprecedented sight of a thirties horror heroine in danger saving herself—albeit with the help of a little divine intervention…

Despite its qualities, The Mummy was not a great success at the time of its release. It is hard to understand why. Perhaps audiences of the time were simply spoilt. 1932, as we have said, was an astonishing year for horror films, and perhaps by its end even the greediest horror fan was sated. It is true, however, that the films has its weaknesses; and that where it does succeed, this success rests more upon its visual power than upon its storyline or its acting—with one notable exception, of course.

Karl Freund’s expert eye shows itself throughout, in its intriguing compositions, in the use made of the production design, and in the gliding cinematography; but Milton Carruth’s editing is also critical, in building the rhythm of the film.

The cast, for the most part, is less memorable. David Manners is left stranded as usual; and disappointingly, Edward Van Sloan is finally given less to work with than it initially seems he will be: one of the most surprising things about this story is Dr Muller’s open terror of the Scroll of Thoth, not a reaction we expect to see. However, over time Muller emerges as just another of the standard “savant” character found in countless films of this era. Arthur Byron is credible as the senior Whemple, though, and Zita Johann makes an interestingly different kind of heroine—and, by the bye, looks exceedingly fetching in the rather daring costumes permissible at this time. Of all the supporting cast, however, it is Bramwell Fletcher whom we most remember, as he wins himself a slice of cinematic immortality in his few brief scenes as the unfortunate Ralph Norton.

(Actually, Fletcher has a second unforgettable moment, when he gets to utter the film’s most infelicitous line of dialogue. When Muller and Whemple are debating Imhotep’s crime, Ralph offers up the suggestion, “Perhaps he got too gay with the vestal virgins!” Try keeping a straight face through that one.)

Still, this is a movie that has won and retained an audience over the decades, not least as the vehicle of one of Boris Karloff’s finest and most nuanced performances. With Frankenstein’s Creature, Dr Fu Manchu and Imhotep, Karloff created three indelible and yet utterly distinct horror characters—and at the same time trapped himself for perpetuity in the realm of cinematic horror and science fiction. However professionally frustrating that must have been for him, we, the fans, can only be grateful.

Various other mummies would shamble across our screens in the years to follow, but despite those films doing what this film does not, that is, positioning their mummies front and centre, not one of them creates even a single scene that carries anything like the power that The Mummy achieves in just a few brilliantly conceived and subtly executed shots. It would not be for almost another thirty years, when Hammer Studios decided to add The Mummy to its list of films in need of an overhaul, that any performance would rival the one that Boris Karloff gives here. With that one exception – granted, an entirely splendid exception – Karloff’s terrifying and tragic interpretation of undead and undying love continues to stand alone.

Want a second opinion of The Mummy? Visit 1000 Misspent Hours – And Counting.

*******************************************************************************

This review was part of the B-Masters’ Month Of The ALTERNATIVE Living Dead.

Even if her costume wasn’t a tip-off that this was a pre-Code movie, the ending certainly is. A heroine saving herself and defeating the villain by invoking a pagan goddess? It would be thirty years or more before you’d see something like that again.

I’ve been watching some pre-Code dramas, and they have a surprisingly “modern” mentality–it’s curious (for me) how much my view of earlier decades has been warped by the Hayes Code.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh, Pre-Code films—! There’s no comparison. When I hear people speak disparagingly of “old films” I just want to tear my hair out—or point them at Universal’s horror movies, or Paramount’s sex comedies, or Warners’ social dramas…

LikeLike

“Our final image is, granted, Helen – Helen – in the arms of Frank; but it is not that which we remember, but rather the unprecedented sight of a thirties horror heroine in danger saving herself—albeit with the help of a little divine intervention…”

Not to mention with the help of a little *female* divine intervention, to boot. The 1932 version of The Mummy is especially meaningful from a contemporary Pagan standpoint, as well as from a general feminist standpoint. This is a fantastic review.

LikeLike

Thank you!

Yes, the sudden wielding of “sisterhood” as a defence against the demands being made upon Anck-es-en-Amon / Helen is quite fascinating.

LikeLiked by 1 person

One of the standard ‘jokes’ in sitcoms a while back (not sure if they still use it as much), if the woman wanted to keep something from the man, she would explain, “It’s a woman thing.” The man would immediately recoil in disgust, and let her do whatever she wanted. (Cooties! MENSTRUATION!) The phrase, “It’s an Eastern superstition” seems to have the same effect.

And, of course, “Why do you want to defile the dead, break holy taboos, and destroy sacred relics?”

“It’s SCIENCE!”

LikeLike

Hey, c’mon, leave SCIENCE! out of it; SCIENCE! isn’t the bad guy here! 😀

Yes, it’s always rather enjoyable when mainstream prejudices are turned back on themselves.

LikeLike

This was the film that put me onto Karloff as an actor rather than just a vehicle for makeup and prosthetics. His Bey steals every scene he’s in.

Johann has rather less to work with, not surprising in a script of this era; but she’s pretty solid in the little she does that’s more than fainting into someone’s arms, including the climactic moments.

LikeLike

What’s astonishing to me is that only a couple of years earlier you can find performances from Karloff that are absolutely terrible. It leaves you wondering where all this artistry suddenly came from—perhaps James Whale’s confidence in him? Who knows?

Yes, I find her a very pleasant change. (Even the mere fact that she’s not the usual English rose is refreshing.)

LikeLike

The other source of inspiration besides Dracula would be Haggard’s “She”.

LikeLike

Gotta watch this again — haven’t since my teens.

LikeLike

Yes, absolutely—which I mention in a different context (upcoming)… 🙂

Certainly you gotta!

LikeLike

Thanks to my mother, this was one of my earliest horror movie memories, not to mention my first experience with our beloved Boris. I saw it early enough that the now-cliched story elements were fresh to me; of course, I was also too young to really grasp the significance of various moments, most importantly the climactic scenes, but that would come with time. It remains high on my all-time great horror film list, and is one I always enjoy revisiting, especially for Karloff.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I understand it, but the pop-cultural privileging of the later Universal mummies over Boris’s performance still makes me seethe.

LikeLiked by 1 person

As is only natural, I think. Still, it’s kind of fascinating what will stick in the public’s collective consciousness (like the “arms outstretched” walk the monster has been given ever since The Ghost of Frankenstein).

LikeLiked by 1 person