“Hi! I’m Chucky, and I’m your friend to the end!”

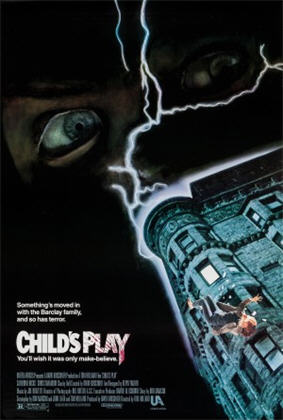

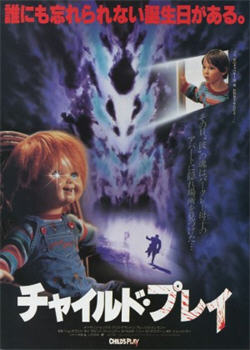

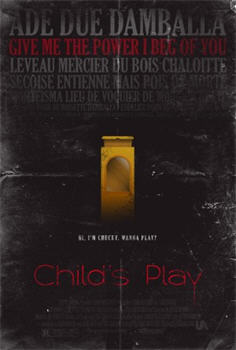

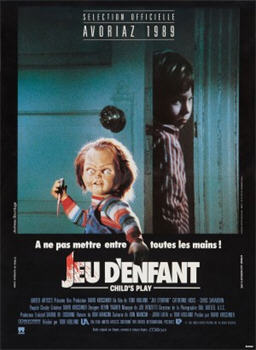

Director: Tom Holland

Starring: Brad Dourif, Catherine Hicks, Chris Sarandon, Alex Vincent, Dinah Manoff, Tommy Swerdlow, Jack Colvin, Raymond Oliver, Neil Giuntoli, Alan Wilder

Screenplay: Don Mancini, John Lafia, Tom Holland and Howard Franklin (uncredited)

Synopsis: Serial killer Charles Lee Ray (Brad Dourif), wounded in a shoot-out with police, takes refuge in a toy store after being abandoned by his criminal partner, Eddie Caputo (Neil Giuntoli). Ray is pursued by Detective Mike Norris (Chris Sarandon) and, in the exchange of gun-fire, is wounded again, this time mortally. Clutching a Good Guy doll in his bloodied hands, Ray performs a voodoo ritual over it. A huge bolt of lightning smashes through the store’s glass skylight, triggering an explosion that causes the store’s windows to erupt, and hurls Norris through the air. Badly shaken but uninjured, Norris staggers to his feet and checks that Ray is really dead… Karen Barclay (Catherine Hicks) tries to give her young son, Andy (Alex Vincent), the best birthday she can, but is unable to afford the Good Guy doll he desperately wants. However, while she is at her job as a department store salesperson, her friend and co-worker, Maggie Peterson (Dinah Manoff), rushes up to tell her that a pedlar in an alley near the store has a Good Guy doll going cheap. Though it is not her break, Karen takes the risk of leaving her counter. She is delighted to find that, though the packaging is damaged, the doll is authentic, and buys it without question. Karen returns to her counter to find that her supervisor has discovered her absence, and cannot argue when he tells her she must work an extra shift that evening. She does have time to pick Andy up from day-care and give him his present: the boy is thrilled with his new “best friend”, Chucky. In Karen’s absence, Maggie baby-sits. When she orders Andy to bed, she is unmoved by his insistence that Chucky wants to stay up and watch the news, and switches off the TV before carrying both Andy and his new toy to his room. Shortly afterwards, however, Maggie finds the TV on again and Chucky sitting in front of a report about Eddie Caputo, who has escaped from custody while being transported to court. She scolds Andy for his disobedience, though the boy insists he did nothing. As Maggie lies on the couch reading while she waits for Karen, a small figure slips through the apartment, finally making noises that attract Maggie’s attention. As she searches for their source, she is dealt a savage blow with a hammer that sends her reeling: she crashes through the apartment’s windows, and plunges to the street below… When Karen arrives home, she finds her apartment building surrounded by police and emergency services, and rushes upstairs in terror. Andy’s safety assuages her first fear, but she is grieved and horrified to learn of Maggie’s death. Detective Norris leads her to the kitchen, pointing out to her some spilled flour on the countertop in which the outline of small footprints may be seen. Karen is outraged by the implication of Norris’s questioning, though the detective admits that none of Andy’s shoes match the prints. However, when Andy comes out of his room, Norris realises he overlooked the boy’s Good Guy sneakers—the sole patterns of which match the prints. Karen intervenes, sending Andy back to bed. He goes—but when alone with Chucky, he sees that there is flour on the soles of the doll’s shoes. He rushes out, announcing that it must have been Chucky on the counter, but neither his mother nor Norris will listen to him. Later, as she prepares wearily for bed, Karen hears the low murmur of voices. She finds Andy sitting with Chucky, apparently in the middle of a conversation—and becomes increasingly disturbed by the boy’s insistence that the doll is alive. In the face of her distress, Andy admits that he was just making up stories; but when Karen has gone, he tells Chucky that he was right: she didn’t believe him…

Comments: We might as well get this out of the way at the outset: I find the doll in this film absolutely terrifying.

I don’t mean Chucky the Killer Doll; I mean the original Good Guy doll. With its moon-face, soul-eating smile and acid-trip eyes, that – that – thing – makes my blood run cold. Quite frankly, once he’s up and around, killing people, performing voodoo rituals and framing small children for murder, it comes as a distinct relief.

It had been some years since I had last watched the original Child’s Play, and I was surprised and pleased to discover just how well it still holds up—and after my recent, almost constant complaints, you probably won’t be surprised to learn that I give much of the credit for this to the film’s screenplay, which is much better than we might expect from the circumstances of its development. Quite a number of cooks were involved in this broth, and the plot underwent significant alteration both before and during shooting; yet the final product is lean, focused and – hallelujah! – internally consistent. The central story arc that carries Charles Lee Ray from voodoo ritual to voodoo ritual is the dominant force in the film, with everything else that happens emanating from that; there are few diversions, and no extraneous subplots. In an era of tediously overlong films that seem afraid to cut anything, this economy of story-telling is striking, and commendable.

Chucky, like a number of his franchise contemporaries, has by now become so much a part of the pop-culture collective that it is almost impossible to imagine how he was received upon the film’s first release. It is certainly true that the special effects in this film aren’t a patch on those in the most recent entries in the series (which, to be fair, are extraordinarily good); but still, the combination of puppeteering, animatronics and the use of child actors and little people (and some stunt work by Ed Gale where needed), by which Chucky is brought to life here, is well-executed and effective. The special-effects work was overseen by Kevin Yagher, who also designed Chucky. (Yagher and Catherine Hicks met while making this film, and married two years later.)

Yet all this would not be nearly so successful without the contribution of Brad Dourif. It is almost shocking nowadays to realise that Dourif has only a “also starring” in the film’s credits. While this is fair enough in the film’s original context—Dourif is onscreen for only a very few minutes at the beginning, and Chucky doesn’t start to talk out loud until halfway through the film—he is now so much the heart and soul of the franchise that, at this distance, it seems as if a gross injustice has been committed.

But what finally puts Child’s Play over the line is that it plays its premise straight. Some mouthiness from Chucky aside, the film is almost startlingly free of jokiness: a correct artistic choice, given that its second half deals largely with the endangerment of a child. The screenplay also finds a nice balance in its handling of both Karen Barclay and Mike Norris, each confronted with the need to accept a horrifying truth – in Norris’s case, two horrifying truths, though only one is true – and neither carrying their disbelief beyond reasonable limits, as movie characters are too often wont to do.

Individuals who stumble over something supernatural and then cannot get anyone to believe them are a recurrent feature in Tom Holland’s work, and the casting of Chris Sarandon as the film’s sceptic adds an interesting self-reflexive edge in the wake of his performance in Fright Night, where he played the opposite role of the disbelieved supernatural entity.

Though various models have been suggested, it seems that Chucky – or rather, his initial, Good Guy iteration – was based primarily upon Hasbro’s “My Buddy” line of dolls for boys. Child’s Play was originally conceived as a satire on marketing and advertising aimed at children; but while elements of this persist in the finished product, the film ultimately gives us something more emotionally pointed.

It is interesting to note that there is a general perception out there that Child’s Play is set at Christmas-time. It isn’t, but the mistake is understandable – and, I would suggest, deliberate – with the film’s emphasis upon the biting cold of a Chicago winter, the opening sequence set in an overloaded toy store, and the desperate chase for a child’s present—“the” present. Though with respect to the latter, Karen Barclay finds herself in the same dilemma the parents in various Christmas “comedies”, what we have here verges rather on tragedy.

There is an admirable subtlety about Child’s Play’s handing of the Barclays. We know that Karen is a widow, that she is struggling as a single parent to make ends meet, that she is caught in the perpetual vicious circle of having to place her child in day-care in order to work and having to work to pay for day-care, that she must put her job before her child even on his birthday. We also know that Andy Barclay is a well-cared-for, much-loved and generally happy little boy—and yet, despite her constant meeting of his real needs, Karen feels guilty, even like a failure, because she can’t fulfil his material wants. The film’s opening sequence, with Andy crushed by not receiving for his birthday the Good Guy doll he desperately wants, and which his mother simply cannot afford, is painful in a way that the film’s horror elements cannot compete with. The overt Christmas feel of the film turns the knife on this point: clearly, Andy’s birthday is quite close to Christmas, meaning that his mother’s slender resources must be stretched to breaking-point and beyond if she is not to disappoint him on either occasion.

All of which sets up Karen’s dash to the alley behind the department store where she works as a salesperson, when her friend and co-worker Maggie tells her that someone there has a Good Guy dolls for sale. The packaging is damaged, but the doll is obviously authentic; and after her scene with Andy, Karen isn’t about to ask questions. (I’d bet she can’t afford the $30 she pays for it, but she doesn’t stop to think about that.) The smile of relief is quickly wiped off Karen’s face, however, when she returns to her counter to find that her supervisor (“Mr Criswell”!) has discovered her absence. She has no leg to stand on when she is ordered to return to the store that evening, to work an extra shift, and no choice but to accept Maggie’s offer to baby-sit Andy for her.

But she does get the chance to pick Andy up from day-care herself, and to watch him while he unwraps his unexpected present.

Each of the Good Guy dolls is an individual, we learn, and this one is called “Chucky”. Karen smiles lovingly as Andy puts the doll through its paces: it blinks, and smiles, and turns its head, and utters its catch-cry: “Hi! I’m Chucky, and I’m your friend to the end!”

Andy spends the evening playing with Chucky and the Good Guy tool-kit that was the present Karen originally bought for him, until his bedtime arrives. This happens to coincide with the TV news, which promises an update on escapee Eddie Caputo; though Maggie is in no mood to listen to what she considers a particularly lame excuse for sitting up, “Chucky wants to watch the nine o’clock news.”

Though it is evident to the viewer what is going on, it is some time before the film has Chucky drop his mask of being “just a doll”. Instead, we get an increasingly creepy interaction between Andy Barclay and his new best friend, which serves to pave the way for Andy’s positioning as prime suspect in various horrors yet to unfold. The interplay between the boy and his not-quite-inanimate object is crucial to aspect of the film, and young Alex Vincent does an excellent job in walking the line between “the doll is alive” and “the kid is delusional”.

An unyielding Maggie packs Andy and Chucky off to bed (and yes, I know “he’s just a doll”; but more careful handling of the latter might be in order—for a variety of reasons); and she is surprised and annoyed some minutes later when she finds the TV back on and Chucky in a chair in front of it, as a reporter announces the escape from police custody of Eddie Caputo, the accomplice of recently deceased serial killer Charles Lee Ray. Her subsequent scolding of Andy for disobedience almost drowns out the boy’s bewildered protestations of innocence.

The stalking and killing of Maggie Peterson is the one place where Child’s Play could be accused of going beyond the demands of its plot: the “something scuttling about” sequence is more protracted than it needs to be, and Maggie somehow convinces herself that she’s “just hearing things” despite finding a spilled canister of flour in the kitchen. The killing itself, however, is both necessary and disturbing in its savagery, the film’s first intimation of a fairly no-holds-barred approach to its story. With a POV shot still disguising the perpetrator, Maggie is dealt a vicious blow with the hammer from the Good Guy’s tool-kit and goes staggering across the kitchen, stumbling into and through the window and plunging to her death on the street below…

The external scenes of Child’s Play were shot on location in Chicago, and here we discover that the Barclays are living in the famous Brewster Apartments. At first glance this seems like a disappointing example of an all-too-familiar cinema (and TV) failing, having characters living in spectacular apartments they clearly can’t afford; but in this case, I think it can be reasonably inferred that this was the Barclays’ home prior to Mr Barclay’s premature death; perhaps, even, that it was using up their resources in the purchase that left Karen in such a difficult situation after she was widowed.

Karen gets home from work that night (on a bus; her use of public transport is another thoughtful touch) to find her building surrounded by police and ambulances. She does a terrified dash to her apartment, rushing past disinterested uniformed officers, and finally discovers an unharmed Andy in his bedroom, being kept company by Detective Norris. Andy tells her that, “Aunt Maggie had an accident”; while Norris breaks the news of her friend’s death. Even through her shock and grief, Karen recognises that Norris’s questions are strangely pointed, and when the significance of his interest in the small footprints in the spilled flour dawns upon her, she is furious and outraged—and not in the least placated by Norris’s revelation that he has already checked and cleared all of Andy’s shoes.

But in fact he hasn’t: Andy’s Good Guy pyjamas have foot coverings with solid soles, and a pattern that matches the prints in the flour.

At this point, Karen puts her own foot down and orders everyone out of the apartment. Norris acquiesces, calling off his men. Karen is just showing Norris himself out when Andy dashes out of his room, announcing excitedly that he knows who left the prints in the flour: it was Chucky.

In the wake of this Norris is all but thrown out—but it is soon clear that he is indeed contemplating the unthinkable, even if he isn’t yet prepared to say so out loud. He tells his partner, Jack Santos, that he wants to see the results of Maggie’s autopsy ASAP, and to know all about the Barclays; he also gives him the bagged evidence he has removed from the apartment: a hammer which he found on the kitchen counter.

Hearing faint voices from Andy’s room, Karen hurries in and finds the boy sitting on the floor opposite Chucky’s chair. At first she sees only the vivid imagination of a lonely child in his reiteration of “what Chucky said”, but as he persists she begins to find Andy’s insistence on what Chucky said and did unbearable; not least the epitaph delivered for Maggie:

Andy: “He said Aunt Maggie was a real bitch and got what she deserved.”

Already overwrought, Karen almost loses it with her son, insisting angrily that Chucky is a doll, just a doll—only to be pulled up short by Andy’s observation (his? Chucky’s?) that, “It’s because of Aunt Maggie that you’re yelling at me, isn’t it?” There is enough justice in this for Karen to feel she has been overreacting about Chucky; but after she has put Andy back to bed, she stops and listens when she again hears voices…

…which begin with Andy telling Chucky that he was right: she didn’t believe him. Chucky’s reply, however – once he has turned his head and seen from her shadow that Karen is still outside the door – is merely another of his catch-phrases: “I like to be hugged!”

The next morning, Karen takes Andy to school, allowing him to take Chucky with him. No sooner has she turned her back than the two are off down the street and, eventually, onto a train, which carries them to the fringes of the city. Andy carries Chucky through increasingly derelict streets populated mainly with the homeless, and finally to a corner opposite an (apparently) abandoned house.

Here Andy plants Chucky on a broken chair on the sidewalk and slips away to pee. Chucky isn’t there when he gets back, however: a POV-shot has already carried us to the house across the street, into the filthy, rat-infested refuge where Eddie Caputo lies sleeping on a dirty mattress—and where the gas is still working…

The massive explosion destroys the house and everything – everyone – inside, and brings the police to investigate—and for the second time in less than twelve hours, Andy Barclay is found at the scene of an appalling “accident”.

Karen is called to the precinct, where – tsk! – Andy is being questioned about his Aunt Maggie. (Interestingly, the boy explains that she fell out of the window because she saw Chucky and got scared; evidently Chucky felt no need to mention the hammer incident…) Frightened by what Norris has told her, Karen pleads with Andy to start telling the truth—otherwise they might take him away from her—but all Andy can do is appeal to Chucky for support—which, needless to say, is not forthcoming; though he does assure Andy that he is his friend to the end…

(Various Chucky puppets were used in this film, with a range of expressions: the look of utter smugness here is devastating.)

Andy reacts to this betrayal with violence that is understandable but which, as far as Norris is concerned, settles matters. It turns out that a doctor from the state hospital has been watching all this through the two-way glass, and he now tells Karen that he thinks Andy should spend a day or two with them.

At home, a shattered Karen confronts what she desperately wants to believe is not just a doll (“Say something, you little bastard!”); but as with Andy at the police station, Chucky does just what he is supposed to do: he smiles, and blinks, and offers platitudes…

Catherine Hicks’ performance is one of the real strengths of Child’s Play, and here she captures Karen’s impossible situation, forced to believe either that her child is psychotic, or – worse – that he isn’t. This scene is pivotal, and it builds to a climax that makes me want to give this film a great big hug.

Of course, saying “climax” might give you the wrong impression; because the highlight of this film isn’t anything big and gaudy, but a tiny moment of utter brilliance.

Since 1988, Chucky has of course become a pop-culture icon. It goes without saying that The Simpsons have riffed on him, via an evil Krusty doll in one of their Halloween episodes—in which Marge responds to the doll’s spirited efforts to murder Homer by ringing customer service. That joke has its origins here, as Karen despairingly inspects the doll’s packaging (“‘He wants to be your friend’—yeah, right”); and as she picks up the box—

—Chucky’s uninserted batteries drop out of it.

And with that—nearly halfway through Child’s Play—Chucky stops pretending and shows himself as the psychotic little killer we all know and love (and Brad Dourif comes into his own as a voice actor). He also takes great pleasure in screwing with Karen, refusing at first to be anything but a doll—until she threatens to throw him into the fireplace unless he talks to her. Then she gets a little more than she bargained for:

Chucky: “You stupid bitch! You slut! I’ll teach you to fuck with me!”

The wrestling match that follows, between full-grown woman and pint-sized doll, ought to be ridiculous, yet somehow it isn’t: the real savagery with which Chucky bites Karen deflates the natural risibility. The fight ends, in any case, with Chucky escaping the apartment, and the building, and disappearing into the night.

Karen’s next stop is the precinct, where she catches Norris on the point of leaving. Her frantic, babbling explanation of what just happened does her no favours, and all she gets out of the detective is a justified, “Whee-ooo.” Even the bite-mark doesn’t convince him. However, Karen’s painful sincerity does have some impact upon him; and when she announces her intention of tracking down the man who sold her the doll, Norris is moved to follow her, albeit for her protection rather than because he expects to learn anything—and just as well, too, because the man wants a little more “payment” for his information than Karen is willing to give. Norris intervenes, and under his not-too-gentle persuasions, the man reveals that he found the doll near the ruins of the toy-store…

I need to reiterate how much I admire the way this film handles the relative beliefs of Karen and Norris. Karen, of course, desperately wants to believe that Andy is telling the truth, though in her heart she doesn’t, until she sees for herself that he is. Norris, meanwhile, having already had to wrap his head around the thought that a six-year-old boy is a psychotic killer, now has to change gears and contemplate a living – and killing – doll.

It doesn’t happen all at once, but neither is there any of that artificially protracted scepticism that movie characters too often display, an insistence on a “rational explanation” past the point where there could be one. Norris may be a sceptic, but he’s also a good detective; and the coincidences – the finding of the doll after his own showdown with Charles Lee Ray, the killing of Eddie Caputo – are becoming too much to ignore.

Karen sees that something in the homeless man’s testimony has deeply affected Norris, and she finally forces him to tell his side of the story—including that, before he died, Ray threatened to kill Eddie Caputo—and him. Norris isn’t prepared to accept just yet that Charles Lee Ray and Chucky are one and the same, however, and he begins to suffer some reaction here, brushing away Karen’s warning that after the killing of Eddie, he’s next; although her parting shot, in which she turns his own words back on him and reminds him how much he hates “loose ends”, hits home.

After dropping her off, Norris returns to the precinct and picks up the file on Charles Lee Ray, meaning to go over it again. When he returns to his car, he finds waiting for him all the proof he could need of even the wildest of Karen’s assertions, as a small figure looms up from the back seat and loops an electrical cord around his throat…

Norris is a smoker, and manages to fight Chucky off with his car’s cigarette lighter. He then has to evade the knife that comes plunging at him through the car seat while still trying to control his car. His latter efforts are thwarted when Chucky slips into the front seat and slams down on the accelerator, sending the car careening wildly through the streets, ploughing through several collisions and finally flipping over in a shower of sparks.

Norris isn’t seriously hurt, but he is trapped; and a dangerous confrontation follows, with the detective warding off Chucky’s knife-attacks and trying to get in a clean shot at him. That he doesn’t do, but he does hit the doll—clearly injuring him in spite of Chucky’s earlier jeering assertion that, “You can’t hurt me!”

The next day finds Karen moving nervously through the now-empty home of Charles Lee Ray—where Norris joins her. The detective has already inspected the premises; but there’s checking something out, and then there’s checking it out after you realise that a dying serial killer may have transferred his soul into a doll; and the occult symbols and weird paintings all over the walls now take on a whole new significance. One of these paintings shows Ray kneeling at the feet of a voodoo master.

Although he doesn’t tell Karen everything that happened the previous night, he does tell her he went over Ray’s file again, and knows who the other man in the painting is; adding that they need to find him before Chucky does…

Too late.

Chucky is already berating his voodoo master, demanding to know why it hurt to be shot, why it bled. The frightened man tells him that he is turning human and that, once the process reaches a certain point, Chucky will be trapped in doll form forever. There is a way out, but his former master won’t share it until Chucky starts doing unpleasant things with a voodoo doll. Then he discloses that Chucky can still transfer his soul into a new body—but it must be the body of the first person to whom he revealed himself as alive, after occupying the doll…

Karen and Norris arrive to find the voodoo master bleeding to death on the floor. As Norris tries to call for help, the dying man whispers to the terrified Karen that she must save the boy; that Chucky must be stopped before he “says the chant”; that, too, as Chucky becomes more human he can be killed, though in his doll form; the target must be his heart.

It is one of Child’s Play’s interesting and, I think, successful choices to stay with Karen after Andy is taken away, leaving the child’s situation to our imagination, instead of wallowing in it—and indeed, what we see of that situation, when we catch up with the boy again, is more than enough: an almost bare room with bars on the window—bars wide enough to let a child slip through, if there was anywhere for him to go, suggesting, as does the height of the barred opening in his door, that Andy has been incarcerated in something designed for adults, although we see later he is in a “children’s ward”. A noise outside draws Andy to the window, and to his horror he sees Chucky working his way up the fire escape at the end of the building. He yells out in terror that Chucky is coming to kill him, but of course no-one’s listening…

Finding out Andy’s room number and getting hold of the keys pose no difficulties for Chucky (you might even say it’s, ahem, child’s play), but the boy outsmarts him, hiding a pillow under his blankets and slipping through the open door once Chucky is occupied on the bed. Andy must then evade not only Chucky but the alarmed staff (now they’re alarmed), with Dr Ardmore finding out the hard way that Andy was telling the truth.

I’ve commented already on the lack of jokiness in Child’s Play, and I think in this sequence we find the reason for it. The film does not hesitate to place Andy in real and imminent danger—but it also accepts that its doing so is no laughing matter. This is the film’s one really outrageous death-scene (allowing death-by-voodoo in context), with Ardmore taken down by a savage scalpel slash before dying under his own electroshock equipment; but even though Chucky gloats over the doctor’s death in a way that would become more frequent over the course of the franchise, here the focus is upon Andy’s terror as Ardmore is murdered in front of him.

Karen and Norris arrive at the hospital to find that Andy has disappeared—but is now the prime suspect in Ardmore’s death. Much to Jack Santos’s bemusement, Norris cuts off his description of the crime with questions about a doll; while Karen hears from a frightened little patient that Chucky was there. She tells Norris she is sure Andy would go home—where, indeed, we find him doing his best to barricade the doors of the apartment, before hiding in a closet, baseball bat in hand.

Chucky is already on his way up in the elevator, looking like a real doll again and attracting the attention of two other of the building’s occupants. The woman isn’t impressed:

Woman: “Ugly doll!”

Chucky [waiting until she’s out of earshot]: “Fuck you!”

Alas for Andy’s brave efforts, he didn’t think about the chimney. A chase around the apartment ends with an unconscious child, and Chucky beginning his voodoo ritual…

As Norris and Karen rush up to the apartment, a violent thunderstorm, rainless but with blinding lightning strikes, breaks directly over the building: the same sort of storm that preceded the death of Charles Lee Ray…

The final showdown in Child’s Play is not without its share of absurdity, to say the least; but by this time the film has built up enough good will that suspension of disbelief is easy. It helps that there is more chasing around than there is adults wrestling with dolls (though there’s some of that); while the fact that Chucky could be hiding almost anywhere in the apartment leads to some real suspense. (I wish people in films like this would stop sticking their faces under the furniture, though. Seriously.) The terror displayed by both Karen and Norris does a lot to sell the situation, with a genuinely nasty note entering proceedings when we see that while Chucky uses weapons in dealing with Norris, he prefers to get hands-on with Karen—a little reminder of just who and what Charles Lee Ray was.

Chucky, of course, isn’t about to go down without one hell of a fight; and in the end it takes the combined efforts of both adults to get the job done, and not without some help from Andy, who in the face of his mother’s danger manages to snap out of a state of near-catatonia to play his part, too.

(It is still something of a shock, though, that Andy gets the closest thing this film has to a parting wisecrack.)

In the end, Child’s Play manages the not inconsiderable task of being both an effective horror movie and great fun. The film’s premise, and its realisation of its living doll, add an inescapable edge of the ludicrous to the proceedings, but at the same time the whole thing is played so admirably straight that the viewer is compelled to take it seriously too. There is even, in the film’s closing moments, not merely the usual tiresome kicker, but a chilling hint that those involved in this horror will struggle to get over it.

The cast does excellent work in this respect. I also very much enjoy the way that, over the course of the story, Karen and Norris become real partners in dealing with the situation, yet without any hint of a romance between them, which so many films seem to consider obligatory, and which is usually so unnecessary.

Child’s Play was a significant financial success at the time of its first release, to the surprise of the critics if no-one else; and franchise-dom naturally beckoned. Chucky has had his ups and downs since then, but this first film retains an engaging freshness. This was a gateway film for many a young horror fan, and remains, with good reason, a favourite to this day.

*******************************************************************************

This review is part of the B-Masters’ HELLO, DOLLY Roundtable.

Was never a huge fan of the franchise but I’ve always admired the work Kevin Yagher and Brad Dourif put into bringing an essentially silly concept to life in an effective and very creepy way. You’re not alone in finding the doll by itself creepy as hell either, it sort of provokes an “Okay, now it feels normal” reaction from me when the thing begins killing people. Good review.

LikeLike

Thanks, Ed! Yes, excellent effects work. It’s interesting too how the voodoo context, the part doll / part human scenario, gives your brain “permission” to buy into this.

I’m glad I’m not alone in my fears! 😀

LikeLike

Yep. Not much creeps me out, but overly realistic doll and large bugs make even a tough guy like me cringe a bit. 🙂

LikeLike

Talking about finding the doll creepy, there have been studies done in Robitics, where they found that there is a point where, the more human the robot looks, the more creepy humans will find it. I suppose the same holds true for dolls – you don’t want them TOO life-like (especially after you’ve seen a few of these movies).

LikeLike

The uncanny valley effect! I think that’s the real creep-factor at the bottom of most of the killer doll/puppet/ventriloquist dummy pictures. They’re humanlike but just enough to be deeply unsettling in and of themselves- making scary movies around them seems like such a simple thing, but it’s difficult to pull off without going over the edge into camp. I’m not a fan of campy horror movies or horror comedies, and I think that its very “straightness” is what makes Child’s Play work so well.

LikeLike

Yes, agreed! I’m still fascinated, though, by how often in these films dolls / dummies not intended to be scary are more scary than their “horror” counterparts. Is this intentional, or is it a misunderstanding of the very principle that Dawn references?—that is, the designers try to make them “more human” but only succeed in making them creeper?

I’m okay with actual horror comedies: what I object to is “straight” horror being undermined with smartarsery.

LikeLike

I’ve been meaning to post this for ages, but wasn’t sure if I could link to other websites here. I make doll clothes, and some time ago I made some dolls out of foam which just might typify the creepy doll syndrome. I think they’re adorable, but they do seem to creep a lot of people out.

http://specialty-crafts.com/prod01.htm

Enjoy.

LikeLike

The younger sibling of a high school friend of mine had one of the “My Buddy” dolls that I think was the inspiration for Chucky. Yes, dear god it was a creepy thing to see in the corner of a room. I always half expected it to move around the room or disappear when I took my eyes off of it. I was ready for this film when I finally saw it. You’re really spoiling us with all the reviews lately! Thank you so much.

LikeLike

You know, I wonder if choosing “My Buddy” as a model wasn’t really about the intended marketing satire, but because they people were already scared of it?

This was an inspiring topic! – although I’m a bit surprised too at how this month played out. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

I make doll clothes to sell, and I pick up dolls at Goodwill to display them (and to sell) at craft shows. I picked up a My Buddy doll and had it on display this past weekend at a show. A family walked by, and the dad picked up the doll to show his young daughter. She ran away screaming.

Maybe she knows something?

LikeLike

I will never forget the ad campaign that SCREAMED it was a killer doll movie. Including the “talk with the crowd shots” in which someone says “Freddy’s dead… long live Chucky”….. Imagine my surprise when I saw it that the set up is a very clever… is this a crazy kid or not… kinda thing. That gives the moment of realization sooo much more impact. Shame we lost it. Damn fine time…. I do enjoy the second one… wow what an excess. But yeah..playing it straight serves this film so well. Love the line at the end “Now do you believe me? … Yeah.. but who’s going to believe me” Made me wanna see everything Brad Douriff did… and I am very happy to have a drop for him for the podcast. Throughout all the sequels… I keep wondering whatever happened to Chris Sarandon’s cop…. oh well. Oh.. did anyone read the comic series when it came out??? It had a … few… very few… moments.

LikeLike

No, I can’t say I ever encountered that.

Yes, I talk elsewhere about “What are they going to tell the police?” endings—interesting to contemplate this one, since it actually is the police!

I think it handles the Chucky / Andy situation cleverly, never really trying to fool the viewer but showing why the cops and even Karen might suspect Andy. In fact knowing the kid is innocent makes it worse.

LikeLike

Which really adds to his predicament in the second one when you realize he is now in the system as a “problem child” but not the John Ritter movie kind. One of the comics had a group of wannabe satanists having found Chucky and trying to do bad magic with it. Chucky kills all but one who says the cops are going to end him… Chucky says “I’m a doll… this is your house… you even have a pentagram on the floor ion blood… you made yourself the killer”…. As always… moments of brilliance

LikeLike

I’ve always found this series surprisingly solid. Part 3 is pretty bad, but I like this first one a lot and the rest are generally solid fun, at the very least. And the most recent one, Curse of Chucky, features a really good performance from Brad Dourif’s daughter in the lead role, and the movie is much, much better than it has any right to be.

LikeLike

I think “much, much better than it has any right to be” applies to all of this franchise but #3; the voice work and puppeteering in the later ones are staggeringly good.

LikeLike

Looking at horror in terms of mundane anxieties, I see a lot of “single working mom / unsupervised child” here, which I’d think of more as a 1970s fear than a 1980s one. But that’s exactly why a lesser writer would have forced in the romance (mom no longer single = normality is restored), and I’m impressed that that wasn’t done here.

LikeLike

There’s a peculiar subtext in genre films where if someone is widowed they are “allowed” to be single; whereas if they’re divorced it’s their own fault they’re single and they have to be hustled into another relationship ASAP. (Often with their original partner, at least if we’re watching a disaster movie or killer animal film.)

LikeLike

That bears comparision with the situation in romances, where the question will be asked “if (he|she) is such a great catch, why isn’t (he|she) taken already”. Now to be fair the characterisation has spread out a lot in the last twenty years, but for a long time a romance heroine who wasn’t in the first flush of youth had to be a widow – because that implied that there was nothing “wrong” with her in terms of suitability for a relationship, she’d just been unlucky. And even that took a while to be accepted; for a long time a heroine had to be a virgin, even if it wasn’t stated explicitly. Divorcées took longer than widows to become acceptable protagonists. And the same applies to the men in a slightly lesser way, though a certain amount of “experience” (though with no inconvenient exes hanging around) was generally assumed.

LikeLike

I’ve never seen any of the Child’s Play movies, except one–Seed of Chucky, which I sought out because of your review. Your review here is great, because like all good reviews, it makes me want to see this film.

LikeLike

Thank you, that’s great to hear! The original film is very different from that later ones but clever and effective in its own (more serious) way.

LikeLike

This was a superb review and analysis, and I think you really hit the nail on the head (and “hammered” it home) about why this film works so well. The special effects might have been improved in later films, but this one really has some of the best acting of any “cheesy” horror film. I think the first two films are the best, with Alex Vincent’s performance as Andy reslly grounding the absurd nature of the films.

Anyway, excellent review. I can’t wait to read more.

LikeLike

Thank you! I enjoy the later films but I love the way that this one plays it straight. I haven’t see the second one for a very long time but now I’m looking forward to revisiting.

LikeLike

Perversely, I have seen the first two sequels, but not the original. Actually, that may be why; I saw those way back in high school, and didn’t care much for either one (although the third was definitely worse). I guess I need to see this one ASAP, because this review has really sold me on it. Maybe Bride and Seed, as well? At least the latter, since Lyz had fun with it. Also, the retelling from a couple of years ago is supposed to be rather good, so perhaps I should find that one, too.

LikeLike

I can get behind Bride… seed… not so much… good luck

LikeLike

I find myself in one of my insomniac moments desperate for something palatable on TV. After The Outer Limits, by sheer inertia I remained for Lost In Space. Then I started to get excited about Voyage To The Bottom Of The Sea. The Deadly Dolls, guest starring Vincent Price.

By all rights I should remember this, but I don’t. If you want to make a killer doll film this is a must see for what NOT to do. I can imagine the producers got excited by the prospect of teaming up David Hedison and Vincent again, nearly a decade after The Fly. It doesn’t work. I think one simple change would have been sufficient to make this much better. The dolls. I’ve seen dust bunnies more intimidating than these Sesame Street rejects. I have famously low standards, but not this low.

Now I must cleanse this from my brain. Hopefully some Jenna Coleman in preparation of my planned trip to Boston next month will return me to sanity.

LikeLike