“It’s alive! It’s alive! In the name of God! Now I know what it feels like to be God!”

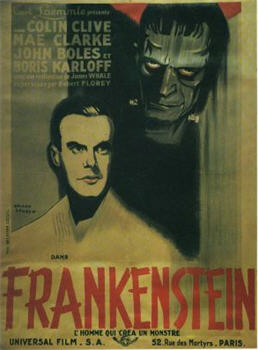

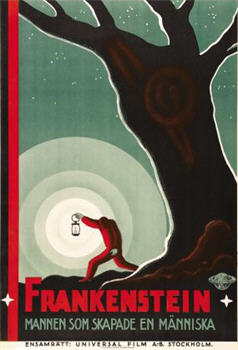

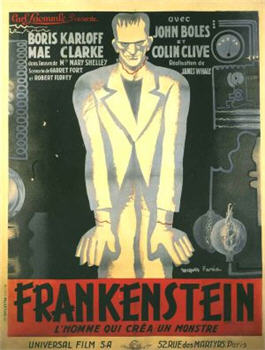

Director: James Whale

Starring: Boris Karloff, Colin Clive, Edward Van Sloan, Mae Clarke, Dwight Frye, John Boles, Frederick Kerr, Marilyn Harris, Lionel Belmore, Michael Mark

Screenplay: Francis Edwards Faragoh and Garrett Fort, based upon the play by Peggy Webling and John L. Balderston, and the novel by Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley

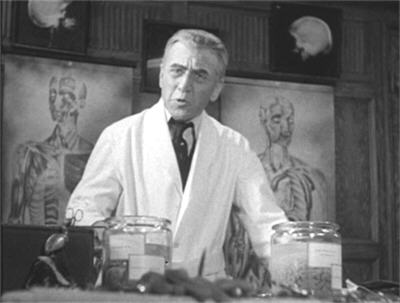

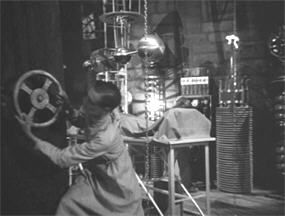

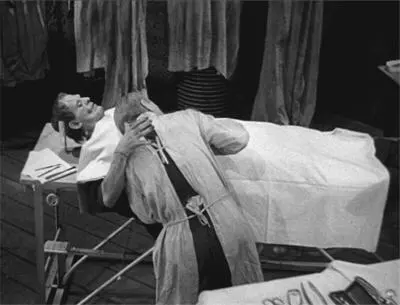

Synopsis: As a funeral takes place, Henry Frankenstein (Colin Clive) and his assistant, Fritz (Dwight Frye), lurk nearby. When the mourners have gone and the grave has been filled in, the two men emerge from hiding, shovels in hand. The coffin is swiftly unearthed… As the two leave the cemetery, Frankenstein points out a body hanging from a gibbet, ordering his horrified assistant to climb up and cut it down. Fritz reluctantly obeys, but upon examining the body, Frankenstein rejects it in disgust, commenting that they will have to get a brain from somewhere else. At the Goldstadt Medical College, Dr Waldman (Edward Van Sloan) demonstrates to his class the anatomical differences between a normal brain and an abnormal, criminal brain. When the class has been dismissed, Fritz breaks into the room. He intends to steal the normal brain, but after being startled into dropping it, in desperation he steals the criminal brain instead. At Frankenstein’s home, the scientist’s worried fiancée, Elizabeth (Mae Clarke), greets with relief Frankenstein’s good friend, Victor Moritz (John Boles). She tells him that although she has not seen Frankenstein for four months, she has received a rambling letter from him in which he insists that his work must come before everything—even before her. Elizabeth begs Victor to visit Dr Waldman, Frankenstein’s university mentor, and he finally agrees. At the last moment, Elizabeth decides to go too. The two question Waldman as to why Frankenstein left the university. Waldman tells them that it was because Frankenstein’s experiments into chemical galvanism were becoming dangerous – and because he began to demand that fresher specimens be provided for his work, without much caring how they were obtained. The aim of these experiments, Waldman reveals, was to create human life… The three decide to see Frankenstein at the ruined watchtower in which he has built his laboratory. At the laboratory, as a violent electrical storm builds outside, Frankenstein and Fritz prepare to conduct a critical experiment. On a surgical table, surrounded by electrical equipment, lies a tall figure covered in a sheet. Fritz recoils at the sight of a hand emerging from beneath the sheet, but Frankenstein admires the fruit of his labours. He tells Fritz that the stolen brain is within his creation—a body made with his own hands… There is a knock at the door. Frankenstein initially refuses his visitors entrance, but upon realising that Elizabeth is outside, reluctantly admits them. Elizabeth and Victor try to talk Frankenstein into coming home with them, but when Victor accuses him of being crazy, the scientist defiantly invites his visitors into his laboratory. Frankenstein tells Waldman that he has discovered the great ray that brought life into the world. Waldman demands proof, and Frankenstein tells him that he shall have it… As the storm continues to rage, Frankenstein and Fritz raise the shrouded figure to the roof of the laboratory, where its electrodes are struck by lightening. The figure is lowered again and, as those gathered watch in horror and fascination, its hand begins to move. Frankenstein howls in triumph…

Comments: It was, appropriately enough, precisely nine months after the beginning of screen horror in the sound era that, amidst a blazing shower of sparks and at the height of a violent electrical storm, cinematic Mad Science was born.

Looking for a quick way to capitalise upon the huge and unexpected success of Dracula, Universal Studios made the obvious move and put into production an adaptation of Frankenstein. As had been the case with its predecessor, Frankenstein’s path to the screen was convoluted, with the finished product bearing only the vaguest resemblance to the tale on which it was supposedly based. Although the novel Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus was in the public domain, Universal chose to by-pass it in favour of the stage adaptation of the story—or rather, of one of them. Frankenstein had been in print only a few years when it was first dramatised; and over the following hundred years and more, stage version followed stage version, each of them altering the story to suit their own ends, and all of them contributing to what many people today consider to be “the” story of Frankenstein and his Creature.

In 1927, yet another interpretation, this one penned by Peggy Webling, was presented upon the British stage by producer-actor Hamilton Deane, who chose for himself the juicy role of the Creature. This version of Frankenstein was Deane’s follow-up to Dracula, and like that play was both acquired for production in the United States, and substantially re-written by the American playwright, John L. Balderston. Unlike Dracula, however, Frankenstein was destined never to see the light of day in America—or at least, not as a play: it was this version to which Universal ultimately acquired the rights.

And so Frankenstein went into production. Without the services of Tod Browning, who returned to MGM after his unhappy experiences with Dracula, the studio hired Robert Florey to direct. Afterwards, Florey contended that much of the film’s scenario was his idea, although screen credit would eventually go to Dracula screenwriter Garrett Fort and to Francis Edwards Faragoh, the latter of whom would put his indelible – and unforgivable – mark upon the whole Frankenstein mythos by coming up with the infamous “criminal brain” twist.

Dracula cast members Edward Van Sloan and Dwight Frye were effectively asked to reprise their earlier roles by playing Frankenstein’s mentor, Dr Waldman, and his hunchbacked assistant, Fritz, respectively. For the roles of Henry Frankenstein (as far as I’m aware, no-one has ever come up with a reasonable explanation for why Victor Frankenstein and his best friend, Henry Clerval, swapped first names) and his fiancée, Elizabeth, Leslie Howard and a struggling ingénue named Bette Davis were touted; while for the Creature, only one actor was considered possible: Universal’s new star, Bela Lugosi.

And then everything started to go wrong.

Frankenstein’s problems began with Lugosi, whose always-robust ego had inflated to unimaginable proportions following his success in Dracula. Although early in production the feasibility of Lugosi playing Frankenstein himself had in fact been discussed, it was not long before, to the actor’s outrage and disgust, he was chosen to play the Creature. Legends abound about Lugosi’s early make-up tests for the role, which claim that he was photographed wearing an ungainly headpiece that seems to have been modelled upon Paul Wegener’s appearance in the 1920 version of Der Golem. Alas, to this day no surviving footage from these tests has ever been located, so we will probably never know for certain.

In the end, burningly resentful at being asked to play a dialogue-less role, and offended by the production team’s refusal (no doubt, entirely justified) to act upon his suggestions for the conception of the Creature, Lugosi quit: a decision for which, no disrespect intended, all fans of horror cinema – all fans of cinema, full-stop – should fall to their knees in profound and endless gratitude. Of such things is history made.

The production upheaval did not stop there, however. Bette Davis was the next to go, her casting vetoed by Carl Laemmle Sr, who found the young actress distinctly unsexy. In time, Leslie Howard also received his marching orders, the film’s ultimate director preferring another actor for the part of Henry.

And yes, poor Robert Florey, too, would soon find himself replaced; certainly not through any fault of his own, whose enthusiasm for the project is well-documented, but simply because another director was, at the time, more in favour on the Universal lot. A former production designer and stage director, James Whale had successfully adapted for the screen his own stage production of the play Journey’s End, then scored a second triumph with his filming of Waterloo Bridge. As a reward, Whale was offered his choice of project, and cast his gaze over all of the films in development at Universal, looking for one that would offer him, as he put it, “strong meat”. He found it, in the tale of Henry Frankenstein and his unnatural creation.

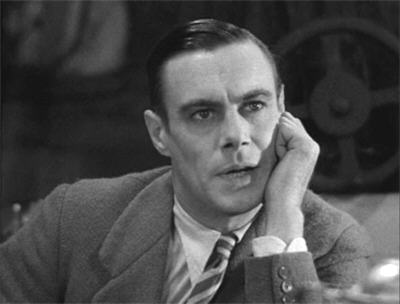

Arriving on the set of Frankenstein, James Whale immediately made his presence felt, insisting upon the casting of two of his former collaborators in the roles of Henry and Elizabeth: Colin Clive, who had played Captain Stanhope in Journey’s End, and Mae Clarke, who had played Myra in Waterloo Bridge. For the pivotal role of the Creature, however, the production team was no closer to finding the right actor—until fate took a hand.

There is no need, surely, for me to recount the story of that historic commissary lunch, or how the artist’s eye of James Whale came to rest upon the distinctive bone structure of an ungainly, middle-aged bit player named William Henry Pratt—aka Boris Karloff. Having struggled for a decade or more to make a career for himself as an actor, Karloff had long since taken to heart the lesson of humility that Bela Lugosi would tragically fail ever to learn. With rueful good humour, he immediately accepted the chance to play an inarticulate “monster”—never dreaming, of course, of the stardom that would follow, nor the cinematic legacy he would create; nor indeed of the physical pain that he would suffer, and continue to suffer long afterwards, as the result of his brave exertions in the role.

Frankenstein is an epoch-making film, like Dracula before it; yet again like Dracula, it must be conceded that it is also a very flawed one; occasionally, even a very bad one. Both films suffer greatly from their slapdash production histories, and in particular from the inability of their writers to overcome the stage origin of the material that they were adapting. In Dracula, this resulted in long, painfully static sequences that gave viewers ample opportunity to contemplate just what was wrong with the film they were watching. In Frankenstein, the problem is less obvious, thanks almost entirely to James Whale’s skill as a director.

Indeed, it is doubtful that Whale ever gave better evidence of his talents than he does in Frankenstein. Perhaps because he had been a stage director himself, Whale clearly grasped what pitfalls he had to avoid, and throughout the film uses imaginative editing techniques and a constantly moving camera to disguise the shortcomings of the scenes being enacted. At one point, Whale even dares, not just to poke fun at his own sleight-of-hand, but to draw attention to it, by having Frankenstein seat Dr Waldman, Elizabeth and Victor Moritz in a row of chairs before the surgical table, prior to animating his creation. “Quite a good scene, isn’t it?” comments the scientist to his “audience”. “One man crazy, three very sane spectators!”

But for all Whale’s heroic wallpapering efforts, the fact remains that the screenplay of Frankenstein, as a screenplay, is simply awful, full of idiotic contrivances and huge leaps of logic. Throughout, things happen with no rhyme or reason. Take Henry Frankenstein’s “disappearance”, for instance. Elizabeth insists to Victor Moritz that she hasn’t seen Henry for four months—since their engagement, in fact. (Hilariously, Victor responds to Elizabeth’s revelation by casually remarking that he recently “ran into” Henry walking in the woods. Apparently, he didn’t see any reason at the time to mention the encounter to Henry’s distraught fiancée.) Yet later on, and despite the tone-setting shots of the isolated watchtower in which Henry is supposed to have immured himself, it seems he’s no further away than just down the road; walking distance even for his annoying old goat of a father. Similarly, the distance of Goldstadt Medical College from the Frankenstein village is strangely indeterminate (summoning up memories of Dr Seward’s travelling Sanitorium in Dracula).

When Henry collapses, following the Creature’s killing of Fritz, Dr Waldman is left behind at the watchtower laboratory to dispose of his student’s handiwork. For reasons known only to himself, the scientist delays taking action long enough for the Creature to develop a resistance to the sedative with which it has been dosed—unfortunately for Waldman. And how, exactly, did Waldman manage to move the unconscious Creature from the basement-dungeon in which we last see it, all the way upstairs to the laboratory!?

Once the Creature breaks loose, impossibilities come thick and fast. Henry and Elizabeth’s wedding preparations are disrupted when Victor arrives with the announcement that Waldman’s body has been found at the watchtower—who found it? Most notoriously (although in justice, something may have been cut here), after the Creature accidentally drowns the child, Maria, her father carries her body through the village, announcing that she has been murdered. Given that there were no witnesses, why on earth would he conclude this? Even more bizarrely, upon being called upon by the Burgomaster to name the murderer, the villagers all shout an answer. Since they’ve been busy all day quaffing the Baron’s free beer and slapping their knees, how could they possibly know!?

Yet before long – although after dark, of course, so that their torches show to best advantage – the villagers are dividing up into search parties, one of them led by—Henry Frankenstein! We can only assume that he hasn’t chosen to break the news of his own involvement in the proceedings. Or revealed that he was the one responsible for the recent outbreak of grave-robbing.

All of this, however, is the kind of thing that may not occur to the audience until after a viewing. The weakest scene in the film – also the one in which the material’s stage origin is most apparent, not coincidentally – is also one of its most famous: the confrontation between the Creature and the wedding gown-draped Elizabeth. Badly structured in all departments (“Grrr!” “It’s upstairs!” “Grrr!” “It’s in the basement!”), the scene culminates with the clumsy, lumbering Creature somehow managing to sneak soundlessly into Elizabeth’s room, and stalk her unnoticed while she restlessly paces the floor. And then, having mysteriously “intuited” which was Frankenstein’s house, made its way there, distracted everyone else in the house and broken in, the Creature simply goes away once it has made Elizabeth faint.

You can understand why all this was left in the script – and you can easily imagine the impact it must have had upon the stage – but for all its iconic value, this sequence is easily the silliest in the whole film. It doesn’t even make sense on a theoretical level, since in this context the Creature could not know who Elizabeth is, or her connection to Frankenstein; or understand that in attacking her, it is indirectly attacking him, as is the case in the novel.

Yet as I say, most of this may only be apparent after the event, or upon subsequent viewings; because there is also much in Frankenstein to love and to admire. So great is the film’s contribution to the development of science fiction on the screen that its influence is felt to this very day. Frankenstein defined “Mad Science” not just for a generation, but apparently in perpetuity. The point at which this film most closely resembles the novel from which its story was drawn is their mutual conception of Frankenstein himself, who is certainly not mad, but rather suffers from a tragic mixture of overweening ambition and weakness of character. One of the main flaws of the novel Frankenstein (which, for all its seminal power, is certainly extremely flawed) is Mary Shelley’s vacillation over the exact nature of Frankenstein’s sin. Is it his desire to play God, or his subsequent failure to take responsibility for his actions?

(In justice to Shelley, this flaw may be more apparent today that it was when her book was first published. When Frankenstein was re-issued thirteen years after its initial success, Shelley, by then beaten down by the tragedy of her life and attempting a shaky rapprochement with her still-hostile family, undertook a conciliatory re-editing her work, putting far more emphasis upon the religious implications of Frankenstein’s transgressions. You nevertheless come away from a reading with the distinct impression that her real concern lay elsewhere.)

Thanks to Frankenstein, the “mad scientist” who “plays God” would become one of the most frequently recurring – not to say clichéd – characters in all filmdom. In time – and not much of it, either – few screenwriters would find it necessary to provide any explanation for the action of their scripts: if you had a scientist in your story, everything was automatically explained.

(Or as a recent incarnation of this stock character chose to put it: “I’m a scientist – that’s what we do.”)

But as is generally the case, Frankenstein differs significantly from most of the films it spawned, inasmuch as it bothers to provide its scientist with motivation – even justification – for his actions. The critical moment of Frankenstein is that which immediately precedes the revelation of the Creature. As Waldman and his former student argue their respective viewpoints, Frankenstein makes an emotional attempt to express the yearning for knowledge that has led him to this juncture, demanding of Waldman whether he has never wanted to, “Do something dangerous”; to, “Look beyond the clouds and the stars”; to discover, “What causes the trees to bud, or what changes the darkness into light”? But all this wins no response from Waldman, and Frankenstein stops himself, concluding his speech with a half-shrug, a sad smile, and one of the most famous lines in all of science fiction: “But if you talk like that—people call you crazy…”

This is a beautiful scene, and beautifully acted by Colin Clive; and fascinatingly, it was not in the shooting script. Legend has it that James Whale himself penned this scene, and it may well be so. Perhaps the most fundamental difference between Frankenstein, the novel, and Frankenstein, the film, is Whale’s evident sympathy for the scientist; sympathy, that is, not for his hubris, but for his desire to create, to explore, to understand; and for the intellectual isolation that his pursuits engender. We have already seen Frankenstein shunned and criticised by those closest to him. His father, the most parasitic of aristocrats, is utterly scornful of the notion of his son working at all. His mentor, Dr Waldman, dubs him “dangerous”; his best friend, Victor, “crazy”. Even Elizabeth, although she says over and over again that she believes in Frankenstein, is speaking from the heart, not the head. The scientist’s pursuits have left him utterly alone.

But for all Whale’s sympathy for Henry, Frankenstein leaves us in no doubt that he is also the villain of the piece. While the scientist’s crimes throughout the film are many and varied, the one action that audiences, certainly modern ones, are guaranteed to find unforgivable is Frankenstein’s rejection and abandonment of his creation.

It is difficult to deal with this aspect of the film without reference to the novel from which its ideas were taken. Mary Shelley’s own life was one of heartbreak and trauma. She herself suffered rejection by her father, William Godwin, after her mother, Mary Wollstonecraft, died only days after giving birth to her. As an adult, Shelley would lose three of her own four children during their infancies. The influence of all of this in the novel is sadly apparent. Shelley’s ambivalent feeling about her own reproductive capacity is evident, but so too is her horror at the thought of what “science” might make possible—namely, male usurpation of the reproductive privilege.

In both novel and film, this perversion of the natural order leads to death and tragedy. The written Frankenstein, however, is certainly the more culpable of the two incarnations, since he repudiates his work primarily because, although he chose his “materials” so as to make his Creature beautiful, it turns out to be ugly; and it is his subsequent cowardice that causes the deaths of those closest to him. The cinematic Frankenstein, in contrast, is appalled by what he perceives to be the Creature’s sub-human intelligence and instinct for violence. Yet both Frankensteins are guilty of the same fundamental error, which is not giving a thought, as they undertake their “experiments”, as to what will happen to the Creature beyond the instant of its “birth”. Their true crime is their irresponsibility; they are, in short, bad parents.

And the film takes another turn here. There is a sense throughout that the precise nature of Frankenstein’s work is somehow a reaction to the predestination of his life: to his inescapable future as the lord of the manor; and to, above all, his forthcoming (and possibly arranged) marriage. Frankenstein’s expression, when his father gives the first of his endless toasts to, “A son to the house of Frankenstein!”, conveys not just embarrassment or reluctance, but antipathy.

Of course, these days, with all that we know about the private lives of James Whale and Colin Clive, it is hard to look at Frankenstein and not read more into it than, perhaps, even Whale himself intended. Still—the fact that Henry Frankenstein reacts to his engagement by disappearing for four months, and upon the very eve of his own wedding chooses to spend his time dabbling in unnatural reproduction, is suggestive, to say the least. And given the way that these very themes positively erupted four years later in Bride Of Frankenstein, perhaps this is not an over-reading of the film at all.

There is a very great injustice associated with Frankenstein, and that is the use of the word “monster” to describe the outcome of Henry Frankenstein’s experiments. Oh, there are monsters in the film, all right, but they are all in human form. The hapless, bewildered, terrified Creature that stumbles out of the darkness of its basement-prison is, on the contrary, one of the screen’s true innocents.

The supreme blunder of Frankenstein is the idiotic subplot of the “criminal brain” stolen by Fritz and transplanted into the Creature.

(And it is idiotic in practical, as well as in dramatic, terms. The script’s contention that there are gross anatomical differences between “normal” brains and “criminal” brains is laughable, of course, but if we play along—shouldn’t medical student Frankenstein have recognised that Fritz had brought him the wrong brain?—and not least because the jar it arrived in was labelled “ABNORMAL BRAIN”!!)

By introducing this “explanation” for the Creature’s behaviour, the film mitigates the issue of Frankenstein’s culpability—or rather, it tries to. It also fails; because, “criminal brain” be damned, the Creature is unarguably the most complete of victims. Rejected by its creator, chained up in a prison, beaten and tortured by Fritz, threatened with destruction at all turns— Of course it becomes violent!

(Apart from anything else, Frankenstein shows a wonderful understanding of the perversely cyclic nature of abuse. Frankenstein’s own rejection by those closest to him does not prevent him from rejecting his own creation; and nor does the suffering of the marginalised Fritz stop him from inflicting the most appalling tortures upon the still more marginalised Creature.)

Yet for all that, there is nothing truly “criminal” about anything that the Creature does. Of the three killings it commits, two are in self-defence, one a pure and tragic accident. Its two premeditated acts of aggression are its terrorising of Elizabeth – whom it does not actually hurt – and its climactic attack upon Frankenstein himself, the man who brought all this misery and suffering down upon it: a justified action if ever there was one.

It is worth remembering in this context that Mary Shelley prefaced her novel with a pointed quote from Paradise Lost: Did I request thee, Maker, from my clay to mould me Man? Did I solicit thee from darkness to promote me? The pity of all this is that we have been made so thoroughly aware of the Creature’s capacity for gentleness, even for affection. It asks so little of its miserable existence – just what we all want – someone to be kind to it…

And it is this, perhaps, that explains the durability of Frankenstein itself, and the regularity with which its themes are resurrected and re-worked in films even to this day. There is nothing and no-one in all the annals of cinema who can touch the Creature for sheer pathos. Perhaps King Kong comes the closest. I have certainly cried over the fate of that beleaguered ape, as I am sure many of you have; yet our sympathy for Kong operates on a different level from that which we feel for the Creature. When we weep for Kong, it is because we feel for his plight; but when we weep for the Creature, it is because we feel for ourselves. It is no wonder that this story continues to resonate so deeply with audiences. Every child who has ever felt itself to be a disappointment to its parents; every individual ever rejected or ridiculed on the score of their physical appearance; anyone who ever felt unloved or unwanted must respond to the Creature and its sufferings. How could it be otherwise?

That we continue to react so strongly to the centrepiece of a film over seventy years old is proof positive that cinematic miracles do sometimes happen. Just think of all the ways that things could have gone wrong here: Frankenstein left in the hands of Robert Florey (a talented director, but no James Whale); an alternative design for the Creature’s look (neither of them the most modest of men, Whale and Jack Pierce both claimed sole credit for concept of the film’s brilliant, unparalleled make-up job; let’s just call it a great collaboration); or, above all, a different actor in the role. Yes, that’s the crux of it: Frankenstein without Karloff is unthinkable; an obscenity. It is the actor, and the actor’s heart, to which we respond. Want to give yourself nightmares? Try this: close your eyes, and imagine this film with Lugosi…

Unlike Dracula, Frankenstein is consistently visually interesting. James Whale was far more the artist than Tod Browning; and, we feel, far more the film scholar, too. Frankenstein throughout shows the influence of the silent European horror films that preceded it; the lighting and the camera-work are heavily Expressionistic. This is particularly true during the graveyard scenes that open the film, which are full of strange shadows and camera-angles (and are highlighted by the incredible moment in which Frankenstein literally hurls dirt in the face of Death), the laboratory scenes, and the climactic chase and battle. Moreover, the relationship between Frankenstein and his Creature (particularly with respect to the victimisation of the film’s so-called “monster”) is reminiscent of that between the hypnotist and his enslaved somnambulist in The Cabinet Of Dr Caligari; while the film’s overall structure and look, and the Creature’s vulnerability to a child who shows no fear of it, recall Der Golem, as its laboratory scenes do Metropolis.

Re-watching this film for the umpteenth time, but perhaps studying it for the first time, I found myself particularly struck by two of Frankenstein’s recurrent motifs. The first, fully in keeping with Frankenstein’s attempt to tamper in God’s domain, is the film’s constant vertical movement. For a film of its time, this is very unusual. Many productions of the 1930s suffer from a slightly cramped feeling, due to the struggles of the cameramen of the time to conceal the limitations of the sets on which they were shot.

Not so Frankenstein. On the contrary, the camera of Arthur Edeson is constantly lifting from the floor up into the air, showing off the sets (and glass mattes!) that are one of the film’s glories. The laboratory, in particular, is a beautiful piece of design, stretching up as it does towards the life-giving lightning storm, and full to overflowing with Kenneth Strickfaden’s fabulous (and, of course, wholly decorative!) electrical apparatus. When the electrical storm reaches its height, Frankenstein and Fritz raise the as-yet unseen Creature all the way from the laboratory floor up to the opening in the ceiling; and when Frankenstein realises that his experiment has been a success, his cries and looks of triumph are also directed up—at Whom, we have little doubt. (The thunderclaps that greet Frankenstein’s infamous pronouncement that he knows what it feels like to be God leave us in little doubt that the heavens are not best pleased with his presumption.)

And so on it goes throughout. Characters are constantly looking up, climbing up, reaching up— This climaxes, of course, in the carrying of the unconscious Frankenstein up into the top of the ruined windmill, where the cornered Creature makes its final stand. xxxFrankenstein, initially intended to set a precedent for all mad scientists to follow, and to die at the hands of his creation, is given a last-moment reprieve here; and significantly, he must fall to live.

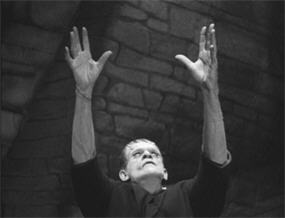

This verticality, this reaching up, leads us into the Frankenstein’s most interesting theme: its constant insistence upon the importance of hands; hands as a point of contact, as a medium for communication; as the means of creation, and as the means of destruction. The first thing we see of Henry Frankenstein in this film is his hand, pressing down upon the shoulder of the over-eager Fritz, as the two wait for the funeral mourners to depart. Frankenstein continues to draw our attention to this motif with his reiterated speeches about the Creature being the product of his hands, his own hands.

(Actually, Frankenstein’s fixation upon what his hands have been up to rather takes us back to the question of the film’s subtext…)

Fittingly, the first we see of the Creature is also its hand, the deep scarred gouges about the wrist evidence of the rough-and-ready acquisition of its component parts; and it is the twitching of that very hand that signals Frankenstein’s seeming triumph. The most memorable hand movement of the film follows, as the Creature encounters sunlight for the very first time, and reaches up in mystified delight, trying to catch the very beams within its stiff, gnarled fingers. Frankenstein soon cuts off that light, leaving the Creature gesturing in helpless bewilderment. It is a gesture repeated after the film’s great tragedy, the accidental drowning of the child, Maria.

Prior to this, there is a moment of inexpressible poignancy as Maria begins to divide up her flowers between herself and her new friend. As she does so, the Creature reaches out and, with infinite gentleness, takes her tiny hand within his, spreading the fingers and staring transfixed at its dainty perfection. And they dare call it “monster”…

(Just for the record— Whale was right, and Karloff was wrong. Undoubtedly the Creature would have thrown the child into the water, not merely placed her in. For it to do otherwise would imply an experience of the world, and a capacity for reasoning, that it certainly did not possess.)

Karloff’s acting during these scenes cannot be praised enough. It is delicate, and full of judgement. We feel infinitely for the poor Creature, but we are also made aware of its capacity for inadvertent violence—never mind what it might do if thoroughly angered. The true wonder of Jack Pierce’s make-up is that it lets so much of Karloff himself show through; the Creature is never a mere object to us.

Post-Frankenstein, Karloff inevitably found himself type-cast; yet he never seemed to resent the fact, that early lesson in humility continuing to serve him well. At worst, Karloff was at least assured of steady employment for the next thirty-five years; and those of us who love horror films should be thoroughly grateful for it—even though, it must be admitted, Karloff the actor was often far, far superior to the material that he was offered.

As for the rest of Frankenstein’s cast, the standard of the acting varies from the good to the serviceable to the frankly appalling. Colin Clive is very effective as Henry Frankenstein, although no doubt some modern viewers will find his fits of hysteria a bit difficult to swallow. In his quieter scenes, however, he conveys a sense of humour, of irony, that makes you understand just why James Whale insisted upon his casting.

Of course, Clive had the advantage of being well served by the screenplay; the other actors had to make do with very little, and on the whole they failed dismally. Edward Van Sloan is far more restrained here than he was in Dracula, and while he doesn’t make much of an impact, he does have his moments—like his wry description of Frankenstein’s scientific shopping-list. (“He wished us to supply him with – other bodies – and not to be too particular about where and how we got them!”) Dwight Frye’s Fritz is simply Renfield with a hunch; the actor gives it his best shot, but the role was an insult. Nevertheless, there would barely be a science fiction film made over the following two decades that didn’t feature a doomed assistant modelled upon Fritz.

Both Mae Clarke and John Boles were far better actors than they were able to show here; Boles, in particular, is stuck with the same kind of “useless wooden block” role that would soon kill off David Manners’ career. As for Clarke, she had a big year in 1931. The irony is that her best-known role is also her least distinguished. Those people wincing their way through Clarke’s plummy, pseudo-British accents in Frankenstein might have a tough time recognising Myra the prostitute of Waterloo Bridge, or the pathetic Molly Malloy of The Front Page, or the gravel-voiced, pajama-clad B-girl on the receiving end of Jimmy Cagney’s grapefruit of The Public Enemy. Worst of all, though, is Frederick Kerr as Baron Frankenstein—an awful character, awfully executed. It’s possible that Whale found the Baron amusing (or that he just liked having Kerr, another old collaborator, on his set), but it’s doubtful that any viewer today will find him anything other than an embarrassment.

There are a few familiar faces amongst the supporting cast of Frankenstein, such as Michael Mark, who plays Ludwig, Maria’s bereaved father. I suffered a moment of strange recognition upon re-watching this movie: twenty-nine years after Frankenstein, Mark would play the not-so-mad scientist, Dr Zinthrop, in The Wasp Woman; and in between the two films, he didn’t change at all—except that his hair and moustache turned white! Also featured in Frankenstein is Lionel Belmore, who plays the Burgomaster—and who would continue to do so, or at least appear in a similar role, in just about all of the Universal horror films that followed this one.

And this brings us to the other enduring legacy of Frankenstein: its creation of that strange, cinematic world that I like to call “Universal-Land”. Where and when, exactly, are the events of Frankenstein supposed to be taking place? The names (place and character) are all Germanic; the sets are pure “Mittel Europe”; yet the aristocratic accents are all British (something not uncommon in American films, of course). The clothes are all modern (circa 1930) and so is the language; but the lack of cars, phones, and batteries place it decades earlier; as does the Baron’s condescendingly feudal attitude to his “peasants”.

And it is the transformation of those peasants late in the film that provides the film’s comic highlight. At one moment, they’re all clad in gypsy dresses and lederhosen and slapping their knees in the village square; the next, the men are clad in the very spiffiest of thirties suits – and, oh Lord, the hats! Check out the hats! – yet nevertheless carrying burning torches (as all good mobs would do in dozens of films afterwards), and wielding farm implements rather than guns. As the decade progressed, the enclosed world of the Universal horror film would grow ever more bizarre and anachronistic, finally becoming a disturbing kind of Neverland; one that steadfastly refused to acknowledge in any way the events that were really taking place in Europe…

It can be hard, these days, to discover in Dracula just what terrified people so in the 1930s. It is rather easier to understand what bothered them about Frankenstein. Consider the subject matter: funerals, coffins, grave-robbing, corpses on gibbets, surgical transplants, reanimation of a dead body, the killing of a child— Make no mistake: for the unprepared audiences of 1931, this was grim, confronting stuff.

And the producers of Frankenstein knew it, too—and were sufficiently worried to tack a prologue onto their film. Even as Dracula originally concluded with Edward Van Sloan, as Van Helsing, reminding people that, “After all, there are such things!”, Frankenstein opens with Van Sloan warning the audience that the upcoming film might, “Thrill – shock – even horrify!” This is partially tongue-in-cheek, of course; the eternal horror film challenge—can you take it? The opening of the speech, however, in which Frankenstein is described as the tale of a man, “Who sought to create life after his own image, without reckoning upon God” is obviously the studio’s attempt to ward off the critical and social attacks it knew only too well would follow.

Well, it didn’t work, of course; the film was roundly attacked; but it was also hugely profitable. The other studios, which had held off even after the success of Dracula, were finally convinced that this “horror” trend was no mere flash in the pan, and scrambled to put their own films into production. The next year, 1932, is one of the richest and most magical in the history of the genre film, with remarkable film following remarkable film – as we shall see in due course.

In truth, neither Dracula nor Frankenstein can match the quality, or the audacity, of many of the films that followed them; but it must never be forgotten that they blazed the way, laying down the foundations for all that would come after. And while many better films would follow, these pioneering works remained, and remain, consistently popular. The two films were even re-released as a double-bill late in the thirties—neither of them quite the works they had been, granted. This was after the introduction of the Production Code, and both films suffered accordingly. In Frankenstein, the most significant cuts were to the scientist’s declaration of his divine presumption, and to the Creature’s drowning of Maria—the latter, of course, leaving behind a far more upsetting implication.

Incredibly, it took decades for this footage to be restored, but thankfully, it did finally happen; and at last we can see, as audiences of 1931 did, Henry Frankenstein in all his hubristic arrogance, and his Creature, in all its piteousness.

Want a second opinion of Frankenstein? Visit 1000 Misspent Hours – And Counting.

Bette Davis was considered unsexy? That changed rapidly.

I read in an interview that Karloff’s makeup was so gruesome that the actress had trouble acting with him. Karloff told her that if it got to be too much, to look at his hand (off-camera). He would keep wriggling his fingers to remind her that it was just make-believe.

This is one of those movies that I always assumed I had seen. It was on in October on TCM, and I watched it, and was surprised at how much I didn’t remember. I felt so sorry for the “Monster” when Fritz starts tormenting it. Frankenstein tells him to stop, but basically leaves him to it.

And, of course, who could forget? “Abby.” “Abby who?” “Abby Normal.”

LikeLike

Only by Uncle Carl; fortunately the Warners were a little more clear-sighted.

There’s a similar story about Fay Wray when making Mystery Of The Wax Museum: she froze when confronted by Lionel Atwill’s makeup. 🙂

Bad parenting and sibling rivalry: nothing messes you up like your family.

Have you seen the sequels? Because of course, lots of Young Frankenstein was taken from them (speaking of Lionel Atwill).

LikeLike

I’m sure I have seen the sequels, but considering how many scenes I didn’t remember in this movie, they would probably all be brand new to me now (major senior moments).

I remember more of the 1950’s series. When I watched them this year on TCM, I thought they looked much too glossy and pretty for horror movies. I prefer the originals (even if I don’t remember them)

LikeLike

I rather like the fact that they’re so aesthetically distinct: it lets me enjoy both without feeling the need to draw odious comparisons. 🙂

LikeLike

I marathon’d the old Universal Monsters “shared universe” back around Halloween, Dracula thru Abbott and Costello meet Frankenstein. Hadn’t watched any of these in almost a decade, and what struck me the most was how much Karloff’s vocalizations get under you skin in this thing. Somewhere between a wounded animal and a mewling newborn. Wow.

LikeLike

Yes! It’s remarkable that Karloff had the confidence to add something like that to his characterisation.

LikeLike

Lyz, we don’t have to “close our eyes and imagine this film with Lugosi” – may I draw your attention to “Frankenstein Meets The Wolf Man” (1943), in which Lugosi actually played the Monster? Dwight Frye is in there somewhere in a desperate attempt to add a touch of authenticity, but you’re quite right – Bela’s bloody awful! Though to be fair, I’m not sure Karloff could have achieved the same degree of poignancy if his pivotal scene in “Frankenstein” had involved wrestling with a very hairy Lon Chaney Jr.

LikeLike

True, though to be fair that’s a post-Karloff interpretation where a bad imitation was probably inevitable (in fact, probably insisted upon). And as you say, it’s not easy to keep your dignity intact while werewolf-wrestling!

LikeLike

Isn’t this what the B-Masters are all about, and the bad-film community more generally? Admitting that, yeah, parts of this classic film are absolute stinkers… but still picking out the good bits.

Lugosi as this heavily-made-up Monster wouldn’t have worked, I agree. But Lugosi as Shelley’s original creature, articulate, unjustly accused? He could have done that, and it would have taken the film in an entirely different direction.

LikeLike

“Home? I have no home. Hunted, despised, living like an animal…”

LikeLike

…speaking of picking out the good bits.

LikeLike

“Classic” doesn’t mean “perfect”, despite what some critics try to tell you. 🙂

I agree that Lugosi would have done better as the Creature-as-written…but then I start thinking about Karloff as the articulate Creature, too…

LikeLike

“Abbie?”

“Abbie Normal.”

“How do you spell that?”

“A, B, N …”

LikeLike