“You can’t kill me again…”

Director: Michael Curtiz

Starring: Boris Karloff, Marguerite Churchill, Edmund Gwenn, Ricardo Cortez, Henry O’Neill, Barton MacLane, Warren Hull, Joseph King, Joe Sawyer, Addison Richards, Paul Harvey, Robert Strange, Kenneth Harlan, Ruth Robinson

Screenplay: Ewart Adamson, Peter Milne, Robert Andrews and Lillie Hayward, based upon a story by Ewart Adamson and Joseph Fields

Synopsis: Judge Roger Shaw (Joseph King) presides over the trial of Stephen Martin (Kenneth Harlan), accused of stealing from the city treasury. Martin is nervous, but his lawyer, Nolan (Ricardo Cortez), and his boss, Loder (Barton MacLane), both notorious mobsters, smile confidently. During a recess, a tearful Mrs Shaw (Ruth Robinson) tells her husband that she and their children have received another death threat, but Shaw does his duty, sentencing Martin to ten years. That night, Loder and his gang agree that Shaw must be disposed of, but in a way that will disguise their involvement. Loder is visited by John Ellman (Boris Karloff), recently released from prison after a sentence for killing his wife’s lover. Ellman pleads for a job and demonstrates his skill as a pianist, but as part of his plan, Loder drives the desperate man away. Ellman then falls in with “Trigger” Smith (Joe Sawyer). Posing as a private detective, Smith hires Ellman to do some leg work: keeping watch on Judge Shaw who, according to Smith, is having an affair. Ellman, who was sentenced by Shaw, is hesitant, but finally accepts the assignment. Meanwhile, Dr Evan Beaumont (Edmund Gwenn) and his assistants, Nancy (Marguerite Churchill) and Jimmy (Warren Hull), are working towards the creation of artificial organs, as a way of prolonging life. Jimmy and Nancy are engaged, but cannot afford to get married. One evening, as the two are driving home, Jimmy’s car is side-swiped. In his anger and frustration – his car is uninsured – Jimmy pursues the other vehicle. The young couple is thus witness to a strange scene: a group of men placing a body in the back seat of a parked car. Those responsible threaten the couple’s lives, and they flee in terror. As they are leaving, John Ellman approaches and climbs into the car – his car – staring in horror at the dead body of Judge Shaw… Ellman is prosecuted for first degree murder by District Attorney Werner (Henry O’Neill), and “defended” by Nolan, who subtly undermines his own case at every opportunity. Ellman continues to insist that a young man and woman can prove his innocence, but when they do not come forward, he is convicted and sentenced to death. As the time of Ellman’s execution approaches, Nancy and Jimmy are unable to live with their guilt any longer, and despite their fears confess their involvement to Dr Beaumont. Beaumont contacts Nolan with the news, and he, concealing his exasperation, promises to contact Werner and, through him, the governor; which he does—very slowly. The call from the governor reaches the prison…just too late… As Nancy sobs in horror and distress, Beaumont urges Werner to intervene and prevent an autopsy on Ellman’s body, insisting that the body be brought to his laboratory instead, and as quickly as possible. With Jimmy and Nancy assisting, Beaumont works feverishly upon Ellman, subjecting his body to a new experimental technique. As the scientists look on in an agony of suspense, Ellman moves—and then opens his eyes… “He’s alive,” breathes Beaumont…

Comments: Although every movie studio was compelled to jump upon the 1930s horror bandwagon, not all of them were equally suited to the task. It is an intriguing fact that the two studios most philosophically distinct from one another, MGM and Warner Bros., were also the two that experienced the most difficulty in exploiting this new and unexpected film trend. These two studios were, of course, also the two to bear most distinctly the imprint of their heads, Louis B. Mayer and Jack Warner. MGM at this time specialised in glossy, star-heavy, “prestige” films; Warners, in socially conscious tales whose unflinching realism drew a certain amount of criticism upon their makers, and in gritty, cynical crime dramas that drew even more. Both studios, each in its own way, specialised in the real world; neither had any feel for, or liking for, the macabre efforts that were bringing in the box office for rival outfits such as Universal and RKO.

Clearly, however, financial necessity dictated that both organisations overcome their reluctance and try to exploit this new market. At MGM, this resulted in a handful of films dealing with bizarre but ultimately explicable events. Even where the supernatural seemed to be involved, invariably it would be explained away in the last few minutes. Warners, meanwhile, inevitably took a different path. The studio did dabble in horror during 1931, producing a version of Svengali starring John Barrymore; a film that, like most early sound horror, was drawn from a well-known literary source; and that had done well enough at the box office for them essentially to re-make it the same year as The Mad Genius, again with Barrymore (and Boris Karloff in a small supporting role).

However, and this is possibly indicative of the studio’s lingering doubts about its entry into the realm of horror, their subsequent genre films were produced not at the studio proper, but through its subsidiary, First National Pictures. First National had begun as a theatre owners’ association, but had expanded into film production before entering into a partnership with Warners in the late twenties, whereby Warners got access to that organisation’s chain of cinemas, and First National was able to employ Warners’ breakthrough sound recording system, Vitaphone, with which the studio had made the pioneering The Jazz Singer and its subsequent sound productions. However, the two studios remained as distinct entities until the mid-thirties, when changes in taxation law made a complete merger of the two the more desirable option.

Whatever uncertainty Warners may have felt about its entry into the horror fray, having taken the decision to do so the studio went all out, making films in the experimental two-tone Technicolor format, and assigning to their productions the director who for two decades would be the organisation’s number one go-to guy, Michael Curtiz. Say what you like about Curtiz as a human being – and many did: Errol Flynn’s famous summation of Curtiz as “that crazy Hungarian bastard” was actual one of the kinder remarks passed – he was a gifted and above all versatile director, and Warners knew what they were doing when they left the development of this new and unfamiliar genre in his hands. Under Curtiz’s guidance, Warners, too, began to profit from the public’s growing taste for horrors.

But here a curious thing happened: Warners, ever the hard-core realists, proved entirely incapable of creating the exotic locations and fantasy worlds that dominated the films of their rival studios. Even MGM, the home of explained-away horrors, tended to set their tales in the same kind of mythical “mittel-European” world as did Universal. But Warners went the other way. The most distinctive feature of the Warners horrors is how very little there is to distinguish them from the rest of the studio’s output. The horror or science fiction aspect of these films – and it is significant that they did usually tend more towards science fiction; obviously, like MGM, Warners preferred something approaching a “rational explanation”, however outlandish it might be – became basically a MacGuffin-ish hook on which to hang all the idiosyncratic Warners features: incompetent cops, nosy reporters, cynical attitudes, and a whole lot of violence, all of it set in contemporary times and on the streets of real cities. In this, Warners would create the first truly American genre films.

By the middle of the 1930s, Warner Bros. had finished absorbing First National Pictures, and had, moreover, gained enough confidence to go on producing horror movies under its own moniker. Much of the studio’s success and self-assurance at this time can be laid at the feet of Hal Wallis, who in true Hollywood style had risen from being a minor functionary in the publicity department to become a producer, and would in time go one to become one of the most successful and influential figures in the history of the motion picture industry. In 1935, as the studio’s executive producer, second in power only to Jack Warner himself, it was Wallis who lobbied for the production of a horror movie, and the signing of Boris Karloff to star in it.

Although his loyalty and gratitude would always compel him to return to Universal Studios whenever they asked for him, Boris Karloff was wise enough to retain the right to negotiate contracts outside of his home base. Consequently, Karloff spent the years 1933 to 1936 moving from studio to studio, his busy schedule leavened only by occasional trips home to England (although he usually worked there, too). Karloff signed with Warners only days after completing The Black Room, a period drama, for Columbia; and found himself in the midst of a production as far in tone and content from that as is conceivable.

Over the preceding few years, Warners had continued their approach of mingling elements in their occasional genre films, and this tactic reached its apotheosis in The Walking Dead. The film is an amazing melding of disparate components, part horror, part science fiction, part crime drama and part religious allegory, which somehow blend perfectly to make up what is arguably the last great film of the first wave of American horror.

You would be hard pressed to find anything more typically Warners than the first third of The Walking Dead. The film hits the ground running, opening with the conclusion of the trial of a local mobster, accused of embezzling from the city treasury. Characteristically, the action is set in a city rotten with corruption, its judicial system bribed or threatened into impotence. Everyone knows the identity of the professional criminals responsible for this situation, but there is no-one strong enough, or brave enough, to do anything about it. These mobsters are secure to the point of brazenness, showing themselves fearlessly at the trial of the man who everyone knows is a part of their gang, while one of their underlings makes open book on the outcome of the trial. Moreover, as we later learn, these men are an accepted faction of their city’s elite, mingling unconcernedly with the wealthy and powerful.

(As District Attorney Werner, one of the few uncorrupted men left, or left alive, puts it ruefully, he knows these men, “Socially as well as professionally”.)

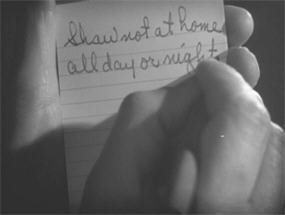

When Stephen Martin’s judge, Roger Shaw, calls a short recess towards the conclusion of the trial, mob boss Loder and his mouthpiece, Nolan, smirk confidently, while reporters call in a verdict of acquittal without bothering to wait for it. In Shaw’s chambers is his tearful wife, reporting another threatening phone-call and demanding to know why his professional duties should take precedence over his duty to her and their children. Shaw stands firm, however, and to the astonishment of everyone gathered, Stephen Martin is sentenced to ten years for his crimes.

Loder and his men gather after this unexpected conclusion. More annoyed at the outcome than concerned for Martin himself, they agree that Judge Shaw must be disposed of. Naturally, the murder of Shaw immediately after the conviction of Martin can only point in their direction, and Nolan urges caution. But not to worry: Loder has a plan, and has found the perfect patsy…

So we meet John Ellman, recently released from prison after a ten year stretch for striking and killing his wife’s lover, in desperate need of a job, and only daring to approach the criminal element in his search for one. Having raised Ellman’s hopes by inviting him in, Loder deliberately crushes them by brusquely cutting short his demonstration of his musical talents and turning him away with insults and abuse.

The devastated Ellman is therefore at his most vulnerable when he “accidentally” runs into a man who introduces himself as a private detective. In reality, this is Loder’s hitman, “Trigger” Smith, who gives an understanding ear and a cup of coffee to the pathetically grateful ex-con, and then offers him a job. Recruited to help keep watch on Judge Shaw’s movements – divorce proceedings pending, is the explanation – Ellman hesitates at first, explaining that Shaw is the judge who sent him up; but finally, persuaded that the job is legitimate, he accepts. So it is that when Judge Shaw is subsequently found with a bullet in him, there is no shortage of evidence that Ellman has been dogging the judge’s steps…

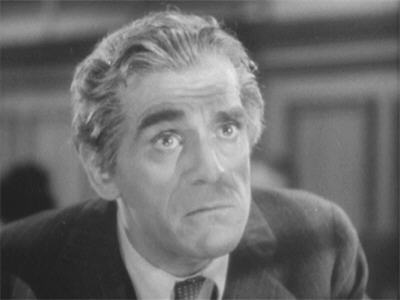

Ellman is put on trial for the first degree murder of Judge Shaw. Nolan defends him – and takes every opportunity to undermine his own case, as the increasingly suspicious D.A. Werner, prosecuting the case, begins to realise. (The eye-acting in this film is marvellous: I love the way Henry O’Neill watches Ricardo Cortez in this scene!) Ellman’s only defence is that there were eye-witnesses who can prove his innocence, a young couple who were on the scene of Shaw’s murder before Ellman got there. But the trial goes on and no witnesses come forward; and despite Werner’s misgivings, Ellman is convicted and sentenced to death.

But witnesses there were; witnesses who, unable to stand their own feelings of guilt, bolt from the gallery of John Ellman’s trial—and yet do not come forward, even when he is convicted…

We have already been introduced to engaged couple Jimmy and Nancy, who were enjoying a rare evening out together – both work long hours – when Jimmy’s car was side-swiped by another vehicle, travelling at pace in the other direction. Furious (his insurance ran out just the day before), Jimmy swings his car around and goes in pursuit of the second vehicle, determined to catch the “at fault” party. In doing so, he gets rather more than he expected. Catching up with the other car, now parked, he and Nancy are witness to something being bundled into the backseat of a third car. Investigating, they realise that the thing is a dead body: Judge Shaw’s body. Even as they stare down at it in stunned horror, the second car returns and the driver warns them that if they breathe a word, they’ll get what Shaw got. Jimmy and Nancy are scrambling back into Jimmy’s car when John Ellman emerges from the darkness nearby. He watches in some puzzlement as they burn rubber to get away—and then he discovers what’s in the back seat of his car…

It is in these sorts of scenarios that Warners always separated itself from the pack. It is not cynicism but simple realism that gives us two young people too afraid for their lives to tell the truth, even as the time set for John Ellman’s execution inexorably approaches. After all, Jimmy and Nancy live in this cesspool of a city; they know the score, and they’ve seen first hand what happened to Roger Shaw when he, a judge, took a stand against the same people threatening their lives. Their cowardice might not be admirable, but it is entirely understandable.

(Jimmy cracks before Nancy, but her terrified pleading holds him silent. It is for this reason that her subsequent guilt is so much the greater.)

It is not until the very night of the scheduled execution that they finally confess themselves to their employer, doctor and scientist Dr Evan Beaumont. Horrified, Beaumont waves aside their lingering fears and insists that Ellmam must be exculpated, whatever the consequences—and he pours the tale of the two frightened witnesses and Ellman’s innocence into the ears of the man who must, Beaumont assumes, have the greatest interest in seeing his life saved: Ellman’s lawyer, Nolan.

Nolan and his criminal cronies are having a companionable dinner together when this fly drops into the ointment. Of course Nolan must play the game, and he does alert Werner to the sudden appearance of the two missing witnesses…eventually. By the time Nolan and Werner reach Beaumont’s office, by the time Werner has heard the story and tried calling the Governor, there are only minutes left before midnight…

The death-house sequence of The Walking Dead is extraordinarily constructed, a masterpiece of chiaroscuro, courtesy of cinematographer Hal Mohr. The terrified Ellman, still clinging to his straws of hope, has them snatched away from him by the warden, who must tell him that the Governor has refused to intervene. As Ellman faces his imminent death, the shadows of his prison cell loom up to engulf him. The warden offers Ellman the traditional last request. “You take away my life and offer me a favour in return,” replies Ellman in a tone that stings even the hardened warden. “Now that’s what I call a bargain.”

But he makes his request, for music. One of Ellman’s fellow convicts, a cellist, plays the piece identified as the doomed man’s favourite, Anton Rubenstein’s “Kamenoi-Ostrow”. (This music will recur as a motif throughout the film.) The remarkable cinematography continues here, with this moving and terrifying sequence entering the realm of pure Expressionism – and, by the bye, giving certain modern directors an object lesson in the correct artistic and emotional deployment of the Dutch angle – as Ellman takes his final walk. He pauses in the doorway of the death chamber, and looks upwards, saying softly, “He’ll believe me.”

Meanwhile, Nolan has belatedly brought Werner to Beaumont’s laboratory, to hear from the now frantic Nancy and Jimmy. The D.A. rushes to get the Governor on the phone, and the Governor in turn calls the warden. Here we get what just might be the defining “Warners” moment of the film (possibly of the decade), as the two guards left on duty in the warden’s office, engrossed in a conversation about the likely make-up of the prison’s baseball team for the following season – their pitcher has been paroled, but they are comforted by the thought of a talented shortstop, just beginning a five-year stretch – take their own sweet time about answering the phone. By the time they do—it is too late…

The grim news is conveyed to Werner and the others, and Nancy breaks down into hysterical sobbing. It is, of all people, Beaumont who here springs into action, insisting that Werner get the Governor back on the line and have Ellman’s autopsy called off at all cost. “Never mind why—there’s no time to lose!” the scientist thunders.

And then The Walking Dead takes a left-hand turn that, even given the presence of Boris Karloff, let alone the exceedingly premature demise of his character, we can hardly anticipate.

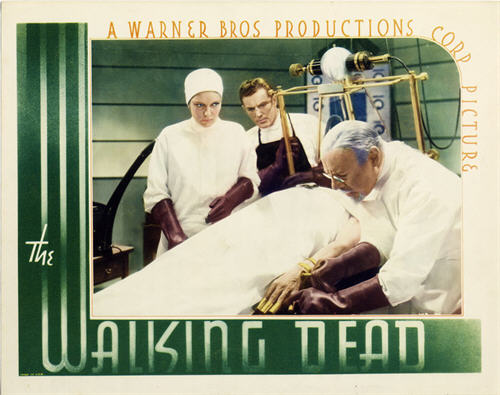

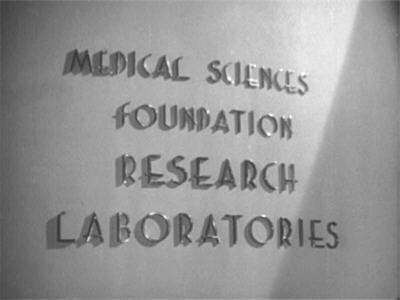

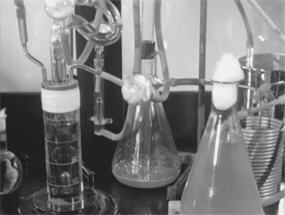

Dr Beaumont is employed at the Medical Sciences Research Laboratories, where Jimmy and Nancy act as his assistants. Science fiction films of the 1930s are full of laboratories, but once again realism wins out in The Walking Dead, which gives us a lab that actually looks functional, rather than just being an eye-catching piece of set design. There’s the usual dry ice fog, true, but aside from that the collection of glass slides, microscopes, flasks, test tubes and racks that we are shown is unusually practical.

Similarly, the actions of Beaumont and his assistants within that lab are purposeful and brisk. Within a couple of brief scenes we establish the specialised credentials of all three of these people, and also the nature of the relationship between them, which is affectionate as well as professional, as we see in Beaumont’s avuncular teasing of his young employees. Beaumont is not just a doctor, but also a scientist, and Nancy is his nurse as well as his research assistant. Jimmy alone is “only” a scientist, which is probably why he is the one left to bemoan a lifetime of comparative poverty, unable to afford immediate marriage to Nancy, and envisioning a future where his professional efforts will be devoted primarily to earning enough money to pay off the tiny engagement ring he has bought for her.

(Another nice touch here: the inference that Nancy will continue to work after marriage, not just because she’ll have to, but because she wants to—and Jimmy doesn’t mind. “That’s okay, we both like working for you,” he replies to Beaumont’s dry remarks on the cost of marriage.)

As for the nature of Beaumont’s research, we are given only a single indication, but that is one that, for the time of The Walking Dead’s production, was highly topical. The first half of the 1930s saw much medical research devoted to developing techniques to allow complicated surgery. Much that today we take for granted has its roots in this work, with the procedures that would subsequently allow open-heart surgery and even organ transplantation finding their beginnings here. One experimental device that captured headlines at the time was the so-called “artificial heart” – a misnomer, but one that stuck – that was developed by Charles Lindbergh in collaboration with the pioneering French surgeon Alexis Carrel. This device, actually a glass perfusion pump, was able to circulate a solution of artificial blood, a growth medium developed at what was then called the Rockefeller Institute, and in this way could keep various organs alive outside the body for up to three weeks. The device was made public in 1935, and it is certainly this the viewer is supposed to think of when Jimmy, leaning towards a pulsating object in a glass flask, comments, “Imagine Dr Beaumont keeping this heart pumping for over two weeks!” The pump is later referenced by name, in the film’s most staggering sequence.

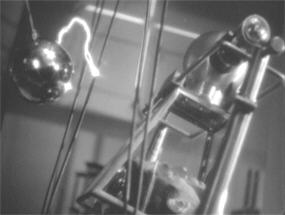

These efficiently staged laboratory scenes establish Dr Beaumont as being at the cutting edge of medical research. Even so, we are hardly expecting what happens following John Ellman’s execution. As Nancy gives voice to her feelings of unbearable guilt and Jimmy gives cool orders – including, “Keep that Lindbergh heart pulsating, Nancy—see that it doesn’t stop!” – The Walking Dead moves from realism and practicality into the glorious world of movie science fiction. The camera pulls back to reveal the kind of laboratory spawned from memories of Frankenstein – or of Metropolis, if you want to go back to the real dawn of movie science, one full of flickering electronic equipment, where pulsing lights and buzzing noises dominate.

In the midst of all this lies John Ellman’s dead body, to which Beaumont and Nancy are attaching electrodes. Beaumont pulls a switch, and the laboratory equipment bursts into electronic life. Electricity arcs leap from point to point, surrounding Ellman’s body. As Jimmy and Nancy look on tensely, Beaumont carries out an examination of his subject—and with an expression of dawning hope, turns to gaze at an x-ray image of Ellman’s chest, where the heart begins slowly pumping. The three scientists gaze in disbelieving wonder as Ellman stirs, and then opens his eyes…and Beaumont, awe-struck, breathes softly, “He’s alive…”

(You can hardly blame the writers for choosing that coda to this extraordinary sequence. It should be noted, however, that Edmund Gwenn’s quiet, reverential reading of these words is about as far from Colin Clive’s hubristic hysteria as you can imagine.)

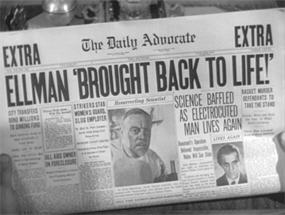

And that done with, The Walking Dead settles back down into the wryly realistic world of Warners, as beside the blaring headlines that proclaim the “modern miracle” performed by Evan Beaumont we see a smaller announcement that Nolan, as Ellman’s lawyer, is suing the state for wrongful death. (He not only does it, but wins a settlement of half a million dollars, a staggering sum in 1936.) However, the John Ellman we see now is not the same man we knew before his death, but a still, silent figure with a stiffened left arm and hand and a white streak in his hair, whose deep, sad eyes seem to hold a universe of unspoken secrets.

Beaumont tries to communicate with him, but Ellman seemingly cannot remember his own name, let alone – and this is the true purpose of Beaumont’s frantic questioning – what happened to him between his death in the electric chair and his resurrection in the laboratory. Speaking with difficulty, Ellman denies both memory and new knowledge. Beaumont’s examination of his charge reveals a blood clot at the base of the brain, which the scientist-doctor believes might be the cause of Ellman’s memory loss. However, he also believes that an operation to remove it might kill the patient.

All this Beaumont explains to Werner, who has become a permanent fixture at the Foundation since Ellman’s return. Werner, like Nancy, is consumed with guilt over his role in Ellman’s death; also like Nancy he is, consciously or unconsciously, seeking absolution from the man he has wronged. His first question, as Beaumont tries to stir Ellman’s memory, is, “Do you feel that I am your enemy?” But far from confessing any feelings of animosity – or otherwise – Ellman can only shake his head to indicate no memory of Werner at all.

It is Nancy who inadvertently reaches Ellman, playing upon the piano in the Foundation’s lounge. Drawn by the music, he joins her there, and she steps aside to listen joyfully as he seats himself to play. She calls Beaumont to the room, and he brings with him another visitor: Nolan, who wanders in to announce not just the settlement made upon Ellman, but that he has had himself appointed Ellman’s legal guardian. As soon as Ellman lays eyes upon Nolan, however, his entire demeanour changes. Rising from the piano, he confronts Nolan and orders him to get out. Nolan, more disturbed by this reaction than he cares to let on, withdraws at Beaumont’s insistence, and the scientist, bewildered not just by Ellman’s display of emotion but the form it has taken, questions his patient once more. “He is my enemy,” insists Ellman, but cannot say why—or more critically, how he knows.

All this is greatly interesting to Werner, who is reasonably certain in his own mind that Nolan is very far from being Ellman’s friend. He explains to Beaumont his own belief that Nolan was part of the frame-up that saw Ellman executed, and Beaumont in turn describes Ellman’s uncanny knowledge of things that he did not know before his death. The two men, each with his own agenda, agree to have Loder, Nolan and their cronies invited to a gathering that Beaumont has arranged, to introduce Ellman to the medical and scientific communities. Rather than putting Ellman on display like a specimen, however, Beaumont decides to have him play the piano for his guests.

(And if the resulting scene seems familiar to you, it’s because it was roundly spoofed by Mel Brooks in Young Frankenstein, where his medical miracle goes into a song-and-dance version of “Puttin’ On The Ritz”.)

Meanwhile, Jimmy is feeling rather on the outer, resenting both the detour that Beaumont’s research has taken, and the hours that Nancy, in her guilt, is devoting to the care of John Ellman—or is it only guilt? “Dr Beaumont has changed. All he thinks of now is finding out what Ellman experienced while he was dead; trying to put his soul under a microscope,” Jimmy says critically. As Nancy defends Beaumont, Jimmy becomes still more agitated, finally throwing at her, “Every time I try to see you, it’s always Ellman, Ellman, Ellman!”

(I’ve always felt that the ultimate romantic humiliation to be found in any horror movie is that suffered by Joan Collins in Tales That Witness Madness, wherein she loses her husband to a tree. Warren Hull’s Jimmy gives Joanie a run for her money here, though, very nearly losing his fiancée to a dead man!)

As the guests seat themselves, Nancy leads Ellman to the piano and he begins to play—and as he does so, and as Werner and Beaumont look on intently, his gaze, deep and baleful, rests in turn upon each of the men who framed him: Merritt, Blackstone, Loder and Nolan. Unable to bear it, the first two bolt; Loder obeys a signal from Nolan and joins them, scoffing at their sudden fears, their conviction that Ellman somehow knows the truth, and dismissing Blackstone’s insistence that they must have Ellman killed again. Then Werner, too, strolls in, satisfied in his own mind of the truth. He and Nolan, also joining them, face off, with Nolan sneering at Werner for “believing in the supernatural”, and Werner responding smilingly that he doesn’t need to: guilt is written all over them.

Nolan tries to dissuade the others, but they ignore his advice and contact Trigger Smith, who agrees to dispatch Ellman for three times his regular fee, payment in advance. Smith is loading his gun, whistling cheerfully, when the door of his room swings open…and Ellman walks in.

“Why did you kill Judge Shaw? That night…I thought you were my friend… You can’t kill me again. You can’t use that gun. You can’t escape what you’ve done.”

Smith backs away in growing dread, and trips over the furniture. As he hits the ground his gun discharges…and he does not move again.

Meanwhile, outside, Blackstone approaches with the pay-off for the hit. He hears the commotion, and the gunshot, and enters the darkened room to find Trigger Smith’s dead body. As he leans over it, a silent figure slips away… Merritt rushes out, and sees a distinctive shadow on the wall as someone walks down the building’s stairs…

That’s enough for Blackstone, who is packing his bags when he phones the news to Nolan. He gets as far as the railway station, and is waiting on the platform when Ellman approaches him.

“Why did you have me killed?”

Like Trigger Smith before him, Blackstone backs away in abject terror…and stumbles right into the path of an oncoming train…

Merritt is the next to succumb to panic – the news of Blackstone’s fate having been broken to him by Werner – and he is pacing his apartment in growing fear when his turn comes. It is a violently stormy night, which does nothing to help quell Merritt’s terrors, and nor does the moment when his two of his three bodyguards quit and leave, sensibly arguing that there’s nothing they can do against a supernatural force anyway. Reassuring himself that the third guard isn’t going anywhere – although the man rightly waves away Merritt’s “generous” offer of his own bed for the night: “You wouldn’t be expecting Ellman to pay you a visit, would you?” – Merritt returns to his own room to close the windows, blown open by the wind – and turns to find Ellman beside him.

“Why did you have me killed?”

Merritt lifts a chair to attack his accuser, but is suddenly gripped by a pain in his chest. He staggers…and falls backwards through the window, plunging to his death.. The third bodyguard – “Betcha”, who was publically making book at Stephen Martin’s trial – rushes back to Loder and Nolan, telling them frantically that he saw Ellman in Merritt’s rooms. Enough is enough, and Loder orders Nolan to make use of his status as Ellman’s guardian, to remove him from Beaumont’s protection. Meanwhile, Nancy and Beaumont discover that Ellman has been getting out of his room at the Foundation – he is found by the caretaker of the local cemetery, wandering in a daze, and returned to their custody – and must confront the fact that Ellman may indeed have played a role in the mobsters’ deaths.

The Walking Dead here reaches a nexus of amazing complexity, as three distinct scenarios, each of them profound and fascinating, begin to entwine. First of all, of course, is Ellman himself, back from the dead with strange knowledge, and, it seems, no clear idea of how he came by it. Ellman’s behaviour during his confrontation with the men who framed him and brought about his death can only be interpreted in supernatural terms. Frighteningly intense as he is as he approaches each of the men in turn, as they die before his eyes there is a complete change in his demeanour. He “comes to” after each death, with dismay and horror entering his eyes; clearly, these are not acts of his own volition. Ellman may be leaving his rooms of his own accord – Nancy catches him at it later, so we know he is – but his presence at each critical place and at each critical time is an act of no human agency: not only could he not know where he has to be, but with Blackstone’s death, he somehow reaches the railway station before Blackstone does. Most significantly of all, however, is the fact that ultimately, Ellman is not responsible for the deaths of his enemies. His presence, his questioning, may panic the men into bringing about their own deaths, but Ellman’s own hands are entirely clean.

As for the particular agency that is acting through Ellman, The Walking Dead is in no doubt about that. For all that they attracted so much criticism during the 1930s – not just during the 1930s, of course, but particularly then – it is notable that these films not only dealt much more frankly with religious issues than any other kind of film, but invariably, either through choice or fear of censorship, expressed a firm belief in the tenets of Christianity. Extraordinarily, The Walking Dead posits John Ellman as a kind of holy hitman, sent by God to avenge his own death—or rather, to be the means of God’s own vengeance.

And it is precisely this possibility that begins to consume Evan Beaumont. As scientists in science fiction films go – and again, this does not just apply to the films of the 1930s – Dr Beaumont is unwontedly benevolent. There’s not a hint of madness, or hubris, in his research, just a genuine desire to serve mankind. However, when it becomes clear that John Ellman has returned from the dead with knowledge he did not possess beforehand, Beaumont’s attitude and aims change. From the beginning, the keynote of his questioning of Ellman is, “But you must remember!”—remember, that is, what happened while he was dead.

It is the scientist’s pursuit of an answer to this supreme mystery that frustrates Jimmy, who begins to contemplate quitting his job if his employer, “Doesn’t come back down to earth”. In time, Beaumont’s hunger to know grows into an obsession. Convinced that the blood clot at the base of Ellman’s brain is all that is preventing him from recalling his post-death experiences, Beaumont decides to attempt an operation to remove it, even though he told Werner earlier that such a procedure would almost certainly be fatal.

Here, finally, what we might call a more “typical” movie scientist begins to emerge, as in his quest for knowledge, Beaumont prepares to risk the life of another. Although he has himself declared the odds of the operation succeeding to be a thousand to one against, it will, Beaumont insists, be worth it. “Secrets from the Beyond! Things that no man has ever dreamed of, will be within my reach!” This indeed sounds like a mad scientist in full flight—but we must not lose sight of what it is that Beaumont is trying to do, nor the full implication of his act. For all that he has raised the dead, there is no hint here of a scientist “playing God”, or thinking of himself as God, or anything remotely irreligious. On the contrary: what Beaumont intends to do is to use his medical and scientific skill in order to prove the existence of God.

The wildcard in all this is Werner. He, like Beaumont, is quite willing to accept that John Ellman has undergone some mystical experience between his death an his resurrection, and that somehow he has been granted the knowledge of who it was that caused his death. Werner is not exactly broken hearted by the sight of Loder’s goons dropping dead one by one—but he is left with the dilemma of Ellman’s involvement. Sympathetic to Ellman’s cause as he is, Werner’s professional ethics demand, should Ellman in fact be guilty of these deaths, that he take action against him. What Werner really wants is proof of Loder and Nolan’s guilt—and it is this that Beaumont promises to give him, by operating on Ellman’s brain.

But before Beaumont can do anything, Loder and Nolan turn up with a court order, demanding that Ellman he handed over to them so that he can be institutionalised. However, Werner notices that the court order has been mis-dated (I always like to imagine the judge, hating having to give Loder and Nolan anything, doing that on purpose). Loder and Nolan, perforce, retire temporarily; and Beaumont makes up his mind to operate at once. Neither do his plans come to anything, however, as it is discovered that Ellman has done another runner. This time, though, Nancy thinks she knows where he might be. Sure enough, she finds him at the Jackson Memorial Cemetery, wandering amongst the graves in spite of the pouring rain. It is so quiet there, he explains, when she questions him; he…belongs there…

Unfortunately, Nancy is not the only one who knows where Ellman has gone. Loder and Nolan, wising up, have been keeping tabs on the Foundation, and have followed Nancy to the cemetery. She urges Ellman to leave with her, but he insists upon staying. “I must. I must.” And again, there is the sense of Ellman having a greater knowledge than anyone else; a knowledge, indeed, of what is about to happen…

Nancy braves the rain in order to find a phone and call Beaumont, and suddenly, within the caretaker’s cottage where she has left him, Ellman sits upright, awareness dawning in his face. He stands and walks outside—and faces Loder and Nolan, who are walking towards the cottage.

It is, granted, a bit difficult to interpret what happens next. We’ve all seen too many movies over too many years when the bad guys, confronted by the good guys, suddenly can’t hit a barn with a bazooka. So it is possible that Nolan, firing shot after shot as Ellman closes in, is missing…except for the bewildered glance he throws at his gun. “Give me that!” snarls Loder, snatching the weapon. He, too, fires and fires—and finally, Ellman collapses. Later we will learn that despite the barrage, only one bullet actually struck him—right in the area of the blood clot at the base of his brain, despite Loder and Nolan standing in front of him.

Nancy screams as Ellman falls. Their mission accomplished, Loder and Nolan leap back into their car and speed away—but they do not get far. On the wet road, on the stormy night, Loder loses control. The car skids, running off the road and crashing into a power pole, which drops its live wires all over the car and the two men within—electrocuting them…

Meanwhile, Beaumont is at Ellman’s bedside, urging him one last time to remember to speak. And Ellman does remember…but he does not speak. “Leave the dead to their Maker,” he cautions Beaumont. “The Lord our God is a jealous God…”

And with that, John Ellman dies…again.

As Nancy weeps, and Jimmy comforts her, a chastened Beaumont gazes out into the cemetery and concedes the impossibility, the impropriety, of his quest, saying softly, “The Lord our God…is a jealous God…”

The Walking Dead is a remarkable little film, exciting, entertaining and thoughtful all at once. It is also, as so many films of this era are, a beautiful example of efficiency in story-telling. Despite being three or four different kinds of film at once, despite its intersecting plot-lines, despite daring to deal with—well, with Life, the Universe, and Everything, it has a running-time of only sixty-six minutes; yet for all that never feels either rushed or skimped. Today’s film-makers, seemingly unable to bring in a finished product that runs less than two hours no matter how shallow or pointless its story, could learn some important lessons from a study of this film.

Again typical of the 1930s, part of this film’s pleasure lies in its ensemble casting, using character actors instead of stars. Edmund Gwenn, then a newcomer to Hollywood, is interestingly cast as Dr Beaumont, and gives us one of this era’s most nuanced scientists, tempted into “tampering in God’s domain”, but finally bowing his head before an unseen Power. Edmund Gwenn and Boris Karloff were fast friends, and the two men loved the experience of working together on this film.

Ricardo Cortez was groomed by his studios as a leading man, but he is far more believable as a slimy mouthpiece like Nolan, grinning to himself as he sabotages his own client, and finishing a leisurely meal before picking up the phone to save a man’s life…not. Likewise Barton MacLane, always more convincing as a heavy than as a good guy – his cops were generally morally suspect anyway – whose Loder wriggles uncomfortably in evening clothes and barely bothers to conceal his criminal activities, even in the presence of the district attorney. Henry O’Neill is his usual reliable self, projecting a moral uprightness that is appealingly tempered by a sardonic enjoyment of the divine retribution to which he is witness.

Romance gets short shrift in this film, but the lightly sketched relationship between Nancy and Jimmy is a nice touch. Warren Hull’s Jimmy is, intriguingly, the film’s voice of caution: it is as a scientist that he objects to what Beaumont is trying to do. Marguerite Churchill made Dracula’s Daughter the same year as The Walking Dead; she is much better here, thanks to superior writing and direction.

There is no mistaking Michael Curtiz’s contribution to this film, in its briskness, its intensity, and above all in the heart lurking beneath the veneer of cynicism. Sadly, the director never made another horror film. During the years to follow, Michael Curtiz would be at the helm of some of the finest dramatic films ever produced in Hollywood. While those who love cinema would not give up those films for any consideration, it is nevertheless hard not to regret that he never tried his hand again at horror.

And Karloff— What is there left to say? The actor’s ability to convey a universe of mysteries with merely a gesture and a look is extraordinary. The sensitivity of his playing, and the shifts in Ellman’s mood as he confronts the men who conspired to kill him, the unsounded depths in his eyes, are fascinating and chilling. This is another of his finest performances, gracing a film entirely worthy of it, something that certainly would not always be the case, particularly over the following decade.

In many ways, The Walking Dead marks the end of an era. Such were the popularity of horror films in the early thirties that the studios were willing to risk battles with the Hays Office in order to get them to the paying public. However, 1935 saw the release of a series of deeply macabre offerings – Bride Of Frankenstein, The Raven and Mad Love chief amongst them – that outraged both the censors and various civics groups to such an extent that a concerted effort was made to quash the production of any more such films. The studios listened, of course, but may not have responded had not the local anti-horror faction found an exceedingly powerful ally.

In England, horror films were even more generally despised. Moreover, the censorship laws meant that even films passed for exhibition could be further cut or banned by local councils. In 1935, an edict was passed banning horror films altogether—removing what had been a major source of profit from the horror market. The studios persisted through 1936, but economic reality finally took its toll. The years 1937 and 1938 comprise a peculiar little watershed in the history of the genre film, being almost bereft of both horror and science fiction, unless we are prepared to stretch the definition of those terms to an untenable degree. (Sh! The Octopus!, anyone?) Horror did recover in time, but it was not the dominant force it had once been. Fantasy movies – often, like The Walking Dead, having a distinctly religious context – began to dominate during the war years, understandably, while outright horror and science fiction were relegated to the realm of the B-film. The first great era of screen horror was over; in The Walking Dead, it found, at least, a fitting coda.

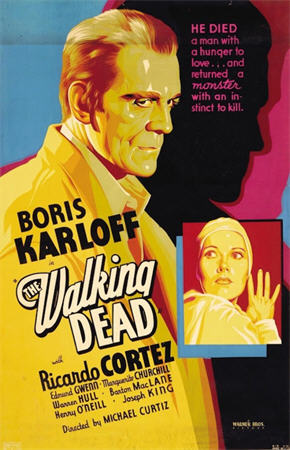

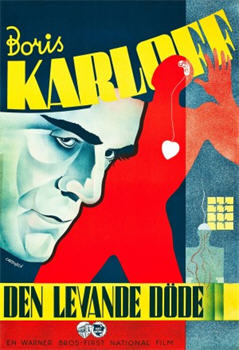

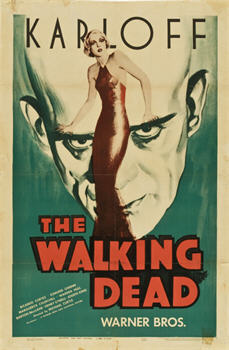

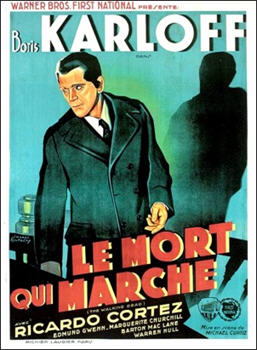

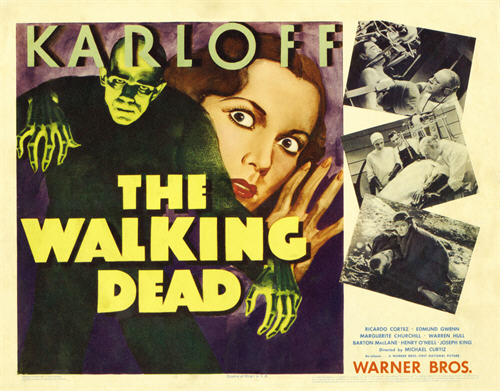

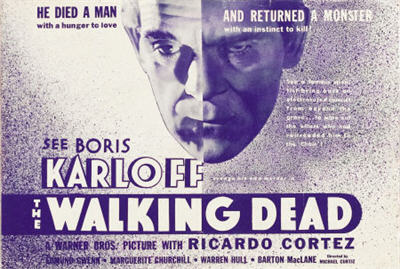

Footnote: I’m fighting an impulse to apologise for the completely inappropriate nature of the advertising art that accompanied the release of this film…but I guess that really isn’t my fault…

Want a second opinion of The Walking Dead? Visit 1000 Misspent Hours – And Counting.

*******************************************************************************

This review was part of the B-Masters’ Month Of The Alternative Living Dead Roundtable.

This review was part of the B-Masters’ Month Of The Alternative Living Dead Roundtable.

Something that struck me about Karloff’s acting in this film,in addition to the way he switches from “vaguely sad ex-corpse” to “mysterious nemesis”; how very small he manages to make himself in the scenes before Ellman dies. He does it not by stooping, but by radiating a sort of servile meekness. He did something similar in The Lost Patrol a couple of years earlier, too, but in that case the emanation was one of cowardice. I love this film as one that lets him show off his power as a performer.

LikeLike

Yes, that’s very true.

Along the same lines, I love the way Ellman’s interaction with Loder is staged—the just-released prisoner in a suit slightly too big for him, against the crime boss in evening clothes. It emphasises both Ellman’s vulnerability and Loder’s bullying demeanour.

LikeLike

This is a similar plot to The Indestructable Man, although Karloff’s character is a lot more innocent.

LikeLike

True, but this is a much superior film in every way.

LikeLike

I believe that the “darn, too late” scene from this movie was used in “Ensign Pulver”, the not-so-good sequel to “Mister Roberts”.

LikeLike

It’s a scenario that’s been used in a number of films, but the way they do it here is a real kick in the guts.

LikeLike

Comparing the screenshots for this movie (especially pre-execution Ellman) to those from The Mummy, it’s hard to believe the same actor played Ellman and Imhotep. Much like Vincent Price, who could go from hapless innocent to malevolent archvillain in (literally) the blink of an eye, Karloff had astounding range. Interestingly, it was the oft maligned genre of horror that allowed both of them to really demonstrate their talents.

LikeLike

I’m always sad that there’s really no such thing any more as “a horror actor”. A much maligned genre as you say, yet it allowed both Boris and Vinnie to show their range in a way that might not have been possible within more mainstream films (although both of them did some excellent work there too, of course).

LikeLike

It’s an odd sort of thing, this “horror at home” – one could see it as the ancestor of the “it could happen you you” non-supernatural horror that came in post-WWII (why yes, I have just read Psycho), but it seems more that, as you say, the scriptwriters and directors were taking their standard vaguely-proto-noir setting and pasting in a horror trope.

(Love that art deco poster with the shot of the operating theatre.)

Wow, all those “coincidental” deaths – presumably influenced by Frankenstein, they were really going out of their way to show new-Ellman as innocent. Not that an all-powerful God ought to need a human agent in these matters.

If this film were being made today, I cannot see any director resisting the urge to put the about-to-die-again Ellman in an arms-outstretched Jesus pose.

LikeLike

I think it was mostly Warners trying to find comfort outside of their comfort zone but yeah, it does inadvertently pave the way for that later horror development.

The “I am doing God’s will” argument is one of many I do not understand…

I don’t think today’s directors resist many urges about anything, sigh.

LikeLike

Pingback: The Walking Dead – scifist 2.0

The lobby card near the top, with Karloff’s face and hands glowing, is so incongruous with the tone of the film and so far from the mood of the other promotional material that I’m puzzled. Ellman doesn’t glow, he doesn’t have a death touch, and he very pointedly doesn’t kill anyone, nor does he want to. The image would have been far more appropriate for Universal’s “The Invisible Ray,” in which Karloff does possess an actual death touch and happily uses it — and which had been released only six weeks earlier!

LikeLike

If it was a pre-release card meant to drum up publicity, it wouldn’t necessarily have to have any connection to the finished product; and it’s quite likely they just reworked some of the art for The Invisible Ray as a cost-saving measure.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Different studios,though. *shrug*

LikeLike

And completely different looks for Karloff. https://i.ytimg.com/vi/t_gsfQS7oxY/hqdefault.jpg

LikeLike