“It’s here – years of research – evidence from all over the world – proving beyond a shadow of a doubt that cats have been exploiting mankind for centuries! We think we’re the masters and they’re merely pets, but we’re wrong. They’re the masters!”

Director: Denis Héroux

Starring: Ray Milland, Peter Cushing, Joan Greenwood, Roland Culver, Susan Penhaligon, Simon Williams, Katrina Holden, Chloe Franks, Alexandra Stewart, Donald Pleasence, Samantha Eggar, John Vernon

Screenplay: Michael Parry

Foreword:

Never let it be said I don’t make things as hard for myself as I possibly can.

When we chose this Roundtable topic, I was quite stumped for a while. Nothing immediately leapt out at me (well…one thing did; with any luck, we’ll get to that later on), although mostly in an embarrassment-of-riches sort of way. As time ticked away, I finally resumed my default position of “in order”, and began working my way through a list of all the Academy Award winning Best Actors and Actresses from the beginning, to see which of them (in my judgement) was the first subsequently to make a terrible genre film. I also decided not to complicate things any further (I know—not like me, was it?) by including the Best Supporting Actors and Actresses in my search; so I was pleased and amused when Will Laughlin went down that road.

Interestingly, it was not until I hit the awards for the films of 1945 that I found what I was looking for—and interestingly again, both the Best Actor and Best Actress from that year qualified for this: Ray Milland, Best Actor for Lost Weekend; and Joan Crawford, Best Actress for Mildred Pierce.

To be honest, I eliminated Joanie almost at once. They get bad press, but I don’t think her genre films are all that bad. Most of them, in fact, are entertaining-to-good. The obvious exception is Trog, which really is terrible; but I can’t even hate that, thanks to Michael Gough’s hysterical hissy-fit of a performance.

Ol’ Reginald, on the other hand— He made some excellent genre films in the sixties; the seventies, not so much. Two of his films did immediately leap out at me: Frogs and The Thing With Two Heads.

And I hesitated. Oh, how I hesitated. Of course, I adore Frogs—rather too much for the purposes of this Roundtable. But then, I adore The Thing With Two Heads, too; and it does have a very high Embarrassed Actor quotient…

And so I hesitated…

…and finally put both films aside for a third one that I had no trouble hating. A perfectly legitimate choice, however, as we find Academy, Cannes, and BAFTA award-winning actor Ray Milland supported by BAFTA award-winning actors Peter Cushing and Donald Pleasence.

And all three of them wasted.

Uh, “wasted”, that is, not “wasted”.

Although you wouldn’t blame them…

♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦

Synopsis: Writer Wilbur Gray (Peter Cushing) slips quietly from his house one night, looking apprehensively over his shoulder as he hurries along the street. From the darkness, eyes are watching… Gray is welcomed into the home of his publisher Frank Richards (Ray Milland), but starts back nervously at the sight of Richards’ white Persian cat. Richards tells Gray that he might publish his new book, but that he is having a hard time accepting Gray’s assertions as fact. A flustered Gray points out that his earlier publications, which at first were considered incredible, are now accepted as the truth. Insisting that he has evidence to support all of his contentions, Gray tells Richards three stories… London, 1912: the elderly, bedridden Miss Malkin makes a new will in which, over the objections of her solicitor, Mr Wallace (Roland Culver), she cuts out her spendthrift nephew and leaves the bulk of her estate to her numerous cats. As Wallace is leaving, Miss Malkin calls him back to her room, giving the housemaid, Janet (Susan Penhaligon), the chance to extract one copy of the new will from his briefcase. Janet then creeps softly to the bedroom door, and learns that the combination to Miss Malkin’s safe, where Wallace places the second copy of the will, is written in the diary she keeps under her pillow. Janet meets secretly with Miss Malkin’s nephew, Michael (Simon Williams), who destroys the will she brings to him and gives her the job of destroying the copy. But Miss Malkin’s cats have other ideas… Montreal, 1975: losing her parents in a plane-crash, the young Lucy is sent to live with her aunt, uncle and older cousin. Her only links to the past are her cat, Wellington, and the occult books that belonged to her mother; both of which Joan Blake (Alexandra Stewart) profoundly disapproves of, and threatens to get rid of. Lucy’s cousin, Angela (Chloe Franks), bullies her and throws her orphaned state at her, and makes more trouble by accusing Wellington of making messes. Joan Blake finally decides that the cat must go, convincing her husband to take it away to be euthanised. But Wellington is not so easily got rid of—and nor are those books of Lucy’s just souvenirs… Hollywood, 1936: Valentine De’ath (Donald Pleasence) and his wife are making a horror movie together when Madeleine is killed in a horrifying on-set accident. The film’s producer and director worry that the project may have to be abandoned, but De’ath suggests that Madeleine’s stand-in, Edina Hamilton (Samantha Eggar), might take over her role. Later, at home, De’ath and Edina openly celebrate Madeleine’s “accident”, as her cat looks on from the shadows…

Comments: I have a very uneasy relationship with The Uncanny—mostly because I can’t quite decide whether it represents a most welcome reinforcement of my own personal life philosophy, or whether it’s the most offensive film I’ve ever seen. I lean towards the latter.

Cats have fangs?

The Uncanny is, in any event, a profoundly schizophrenic film, which can’t make up its mind whether cats are a force of retribution sent to punish evil humans, or whether they themselves are evil, and something that human beings must guard themselves again. The action repeatedly contradicts the script, showing us the former while the cast insists upon the latter. The viewer, consequently, is at a loss to know whether he or she is supposed to be horrified by the fates meted out to various characters in this film, or sickly amused, in an EC Comics kind of way. The screenplay zig-zags between these two attitudes so frequently, in the end it’s easier to throw up your hands and not feel anything at all.

Anything except personally affronted, that is. Now—I know that there are some genuine ailurophobes out there, with whom I can only sympathise; and I also know that there are people who just plain don’t like cats. I don’t understand that, but I accept it. However, neither of these positions justify the wearying lack of imagination with which cinema handles cats, maintaining a monotonous “cats are eee-vil” stance which gives rise to a most hateful corollary: that violence against cats is funny. Both of these positions make their appearance in The Uncanny, I am sorry to say.

Putting philosophy aside for a moment, there are reasons beside its screenplay and its attitude why The Uncanny fails not just as a horror movie, but a movie generally. For one thing, from a genre point of view it throws away the opportunities presented by a first-rate cast. Peter Cushing and Ray Milland appear only in the framing story; and although Donald Pleasence gets a lot more screen-time, he is also featured in the most problematic of the film’s three stories.

But the overriding problem with The Uncanny is that in order to work, it requires the co-operation of that most unco-operative of animals, Felis domesticus. Now, as any enslaved human could tell you, cats are the most perfectly natural drama queens. Better yet: they do the most bizarre things, and pull the most bizarre faces, quite spontaneously, as part of their normal behaviour—as their dominance of the internet illustrates.

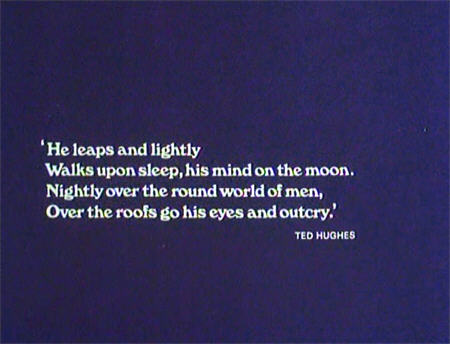

…………………………………………….‘She sleeps profoundly, her mind on nothing

…………………………………………….Stretched full length, stealing bed and blankets.

…………………………………………….But then she snuggles close and purrs

…………………………………………….And you forgive her.’

…………………………………………….—Anon.

However, getting them to do such things – or, indeed, anything – on cue is quite another matter; and while there have been some talented feline performers over the years, the vast majority of cats will, rather, respond to human commands (or pleas) with an expression of mingled disinterest and contempt that says quite as clearly as words could do, “You want me to do what, now?”

And there’s a second, parallel problem with basing your horror movie around cats, although perhaps only real cat-lovers would be thoroughly aware of it. While movies insist that cats vocalise both loudly and frequently, in fact, more than most animals, they communicate predominantly via body-language; it is in most situations perfectly possible to tell a cat’s mood by its posture and its movements, or even just the look in its eyes.

Watching the feline stars of The Uncanny, very rarely to we see anything that suggests “angry cat”, far less “violent cat”. At various times we see “frightened cat” and “startled cat”; but the mood most frequently on display here – a sign that, overall, the cats were being appropriately handled, which is good to know – is “happy cat”. That light-toed, jaunty walk, with tail held high and its tip curled over, is the sign of a cat contented with its lot; the signifier of a retributive force of eee-vil it is not. We’ve all seen plenty of films in which a “savage” dog wags its tail frantically all the way through its big scene. To the feline cognoscenti, the sight of several cats trotting in the same direction with tails held in the air is no less of a giveaway: the message expressed is not, “Die, human, die!”, but, “Ooh, tuna!”

Yet none of this ever seems to dissuade film-makers, particularly horror film-makers, from trying to build their films around cats—even though the attempts to convey their essential eee-vil usually end up consisting of an aggravating mixture of: (1) dubbed in yowls and hissing noises that clearly aren’t issuing from the animals in question; (2) “attack” scenes consisting of unfortunate cats being thrown at even more unfortunate stunt-people; and (3) lots and lots of shots of cats just sitting there, to which we are apparently supposed to react with a horrified cry of (apologies to both Dan Ackroyd and Dr Freex), “Eek! A cat!”

I hope you enjoy this shot, because you’re going to see it A LOT.

All of which The Uncanny has to an embarrassing degree.

This film was a British-Canadian co-production (explaining the second, Montreal-set sequence), and was overseen by Milton Subotsky, still trying to wring a buck from horror anthologies as late as 1977. In contrast to most Subotsky productions, The Uncanny only has three linked stories, and I’m not sure any of them benefits from the longer running-time. Far too many scenes consist of repeated shots of cats doing “scary” things like lying down, peering at things, and blinking. And by repeated, I mean the same shots re-used.

After opening credits that are one of the most enjoyable things about the film (albeit they suggest that Robert Ellis didn’t much care for his remit, inasmuch as those shots overtly intended to make cats look “scary” are either silly or cute), we begin with the framing story, to which Peter Cushing and Ray Milland are entirely confined. After hurrying through the night in a state of clear apprehension, author Wilbur Gray meets with publisher Frank Richards, to discuss his latest manuscript—a terrifying exposé of the fact that, “Cats have been exploiting the human race for centuries!”

Richards, although he published Gray’s earlier books on “flying saucers” and “the pyramids” (ah, the seventies!), baulks at this on the grounds that, “I’m not convinced that the public is ready for the story.” To my mind, a more cogent objection would have been, “Try telling us something that we don’t already know.”

Richards then inquires, “Do you really believe this?” – to which Gray replies (with that patented Peter Cushing sincerity), “I believe everything I write!” He then exchanges glares with Richards’ cat, a half-grown white Persian that goes by the unfortunate sobriquet “Sugar”.

“Another day, another human being subjugated!”

(A good piece of casting: any cat is capable of delivering a mere dirty look, but no breed has more aptitude for really giving stink-eye than the Persian.)

Gray launches into his first story of feline mayhem: “the Malkin story” (a play, I suppose, on Grimalkin), which opens with elderly cat-lover Miss Malkin cutting her greedy, spendthrift nephew out of her will and leaving her entire estate – minus one good dinner, Michael’s entire bequest – to her cats, of which there are very many. Their leader, a very handsome calico, has the privilege of lying on the bed under Miss Malkin’s stroking fingers. Her solicitor, Wallace, is dismayed by the will but knows better than to try and dissuade his stubborn client.

(Throughout this film, the cats are encouraged to certain actions by, obviously, bits of food being tucked here and there. We get a particularly funny example here, as a tabby takes an intense interest in the contents of Roland Culver’s briefcase.)

An interested spectator / eavesdropper is Janet, the maid (“That girl will be the death of me one day,” observes Miss Malkin, in the first of the film’s exceedingly heavy-handed pun-lines, also EC-like), who lurks and pries so successfully that she manages to steal one copy of the will, and learns where to find the combination of the safe that holds the other. Janet is secretly involved with Michael, and breaks the bad tidings to him over dinner at a restaurant that, honestly, no gentleman would be seen taking a housemaid to, even if she was wearing her “best”.

(In a nice joke, Michael is played by Simon Williams, at this time best known for Upstairs, Downstairs, where his character also had a penchant for interfering with the maidservants.)

“Fancy ending up in a film like this! It’s enough to make a chap’s hair fall out!”

“Tell me about it.”

Michael persuades Janet to steal and destroy the second will, in exchange for what we later learn is a promise of marriage.

Yeah, right.

That night, Janet slips silently into Miss Malkin’s bedroom and extracts her small diary, in which the combination is written, from beneath her pillow. She succeeds in opening the safe, and is just removing the will when the calico cat jumps up onto the bed, waking Miss Malkin, who immediately denounces Janet as a, “Wicked, wicked girl!” Janet takes the ensuing threats of hellfire with something like equanimity, but when Miss Malkin picks up the phone to call the police, her response is to snatch up one of the pillows. “I was hoping I wouldn’t have to,” she says, more in sorrow than in anger, moving towards the appalled Miss Malkin. “This was Michael’s idea…”

But no sooner is the deed done than Janet finds herself dangerously outnumbered. When she goes to pick the will up from the floor, where it fell during the confrontation, she finds it guarded by several cats, who defend it with vigour. Here we have the film’s first open suggestion that not only do cats understand every word we say, but that they are capable of grasping concepts such as “law” and “inheritance” and “murder”.

I can only say again: tell us something we don’t already know.

The back of her hand shredded, Janet makes the mistake of retreating. She gets as far as the bottom of the staircase, then realises that she’s surrounded. We get a series of shots of cats sitting still and gazing about quite calmly, while some frantic dubbing of hisses and snarls tries to convince us that they’re massing for an attack.

There’s something fishy going on here…

The attack, when it happens, consists of shots of “Janet” – or her stand-in – having cats tossed at her by someone off camera, all of which then run away as fast as they can. One cat does indeed look like it’s inflicting some damage, as it lands off balance and tries frantically to hang on with its claws as the barrage continues.

A bloodied and battered Janet finally scrambles to her feet and makes a run for it. (Amusingly, most of the cats that are supposed to be chasing her run past her. My suspicion is, someone was making a noise like a can-opener.) She manages to beat the cats into the pantry, where she shuts the door and, hilariously enough, shoves a chair under the door handle. Evidently in all the time she’s been working for Miss Malkin, Janet has never noticed that cats don’t have opposable thumbs. I mean, why do you think they keep us around?

Of course, having barricaded herself in, Janet then realises she’s trapped. There’s no second door, and only one window, high up and barred.

Some sloppily edited scenes let us know that time is passing: shots of the outside of the house, Janet dozing, Janet eating bread, Janet dozing, Janet eating cheese, outside, Janet dozing, Janet licking the dried blood off her hands, outside, Janet dozing, Janet steeling herself to spread cat food on a dry crust…

At one point, in a night-time scene, we see Michael lurking outside in a cab, evidently hoping for good news on the Operation Snuff Auntie front; but at the sight of a bobby on the beat, he makes himself scarce.

(Oh, come on— Who feeds slop like that to their cats!? Their servants, yes, but not their cats.)

“After giving the matter much careful consideration, I have come to the conclusion that people suck.”

At another time, the milkman comes to the house. Janet climbs up on a chair and gazes out the window at him, but makes no move to attract his attention, presumably on the grounds of Operation Snuff Auntie having been successfully carried out. The milkman leaves, and it’s back to the game of trying to find something to eat. It seems to me that for a house this size, it’s rather ludicrously under-provisioned; possibly because it’s also ludicrously under-staffed.

At last, after one of her periodic glimpses through the keyhole, Janet finds the coast clear. She creeps out, knife in hand, but instead of leaving the house, hesitates at the bottom of the stairs, thinking again of Michael’s promises. Finally she tip-toes up to Miss Malkin’s bedroom to have another go at securing the will. As she goes, we are offered the rather bemusing sight of a trashed house—including such mystifying details as the paintings on the wall being tilted, drawers pulled open, and cupboards ransacked. Uh…the cats did that?

(I guess we have to forgive Janet her frantic barricading of the pantry door: evidently these cats were quite capable of using a battering-ram to break it in.)

The will is where she left it, on the floor with two cats sitting on it. Janet makes her way around to it, but is suddenly startled by the phone ringing. Janet lets it ring and makes a try for the will, but a well-wielded set of claws both stops her and disarms her.

And it is only at this moment that the not-particularly observant Janet sees what’s on the bed, namely—what’s left of Miss Malkin. Which isn’t much. Not with so many mouths to feed…

PROOF POSITIVE THAT CATS ARE EEE— Hey, wait a minute…

That’s enough for Janet. She bolts towards the stairs, where a cat trips her down them. The phone rings again, and this time Janet tries to answer it, but the cats aren’t having that. We then get another mass attack scene, which just goes on and on and on: Janet screaming and flailing, cats flying through the air, cats running downstairs, more screaming and flailing, more flying, more running, more flying…

It’s Wallace on the phone; Michael is with him. They decide to go to the house and see for themselves why no-one is answering. They pick up a policeman on the way. The bobby forces his way in, and the three men are immediately confronted by the sight of Janet’s dead body. Curiously, her neck appears to be broken. I’m not quite sure how the cats managed that, but I guess if they can ransack a house, they can do anything. We’re straying into a wizard did it territory here. (My actual answer is, more sloppy editing. Someone changed their mind about having her die in a fall.) Meanwhile, her one exposed arm looks more mummified than chewed on: how long did Michael wait to hear from her?

Michael then makes a dash upstairs, presumably hoping to secure the will before the others get up there. He notices that Auntie’s somewhat the worse for wear rather quicker than Janet did. However, by this time the only cat on the bed (resting, not eating) is the calico, which gives him a long look. Michael continues to edge towards the will, currently guarded by three cats (two of which are licking Janet’s blood off it). As Michael bends down, a lone tabby launches itself from the bed’s canopy and latches onto his throat. The sounds of the struggle bring Wallace and the policeman. They burst in to find Miss Malkin’s gnawed corpse (the cats having settled in for the second course), and Michael—dead of history’s most bloodless jugular severing.

They also find the will…

“I’m the party of the first part. And this is my legal advisor, Tiddles.”

Cut back to Gray and Richards, and the best illustration of just how philosophically confused this film is. Richards excuses the owner-munching on the grounds that the cats had to eat something, but then objects to Gray’s reading of the situation: “To suggest that they decided to deliberately avenge the murder of their owner…”

Wait a minute. Let’s back up a bit. Isn’t the premise of this film that cats are, well, eee-vil? Surely, then, this was about the cats defending Miss Malkin’s will for their own gain…and then eating her corpse just to show what ungrateful little bastards they are?

But bizarrely, Gray – propounder of the eee-vil theory – casts the cats instead as vigilantes, avenging Miss Malkin and making sure that Michael and Janet don’t get their grubby hands on her property. That’s hardly an example of cats as exploiters of mankind.

And another thing— Frankly, the gnawed-corpse gross-out is pretty stupid, given the time-frame. These are, after all, spoiled domestic pets; I sincerely doubt that such an idea would have crossed their minds, certainly not in such a short time-frame; and even if it did, it is much more likely that they would have gone and sat in front of their bowls, waiting for bits of Miss Malkin to magically appear in them, like their food always does. But if we must have corpse-gnawing, and obviously we must— Why didn’t they eat Janet’s corpse? You could still have your gross-out, and it would fit the story infinitely better.

Richards here interrupts Gray’s blathering by getting up to let his own cat out, which sends Gray into another panicky fit. With Richards still out of the room, Gray crosses to the window, where he observes Sugar nose-to-nose with another cat: a perfectly standard piece of feline interaction that sends Gray into yet another tizzy. However, by the time Richards responds to Gray’s call, Cat #2 has wandered off. “But—there were two cats!” gasps Gray. “I saw them! They were talk—”

I guess sometimes the jokes do just write themselves.

Here he stops himself. Richards turns the conversation back to the book; while outside the cats begin to mass…

(…around a pile of food on the pavement, but we’ll try to overlook that.)

The second story is a modern one, taking place in Quebec only two years previously; and while it is referred to as the story of “Lucy”, it is actually about the disappearance of a second girl, “Angela”.

A social worker delivers a young girl, whose parents were killed in a plane crash, to her exceedingly reluctant aunt and her almost personality-less uncle. To the aunt’s horror, the kid brings along her two remaining comforts: a small collection of books on the occult which belonged to her mother, and her cat, Wellington (a handsome black feline that was either of an amazingly placid temperament or, I fear, lightly sedated: the poor thing is hauled around here like a sack of potatoes, almost without protest). Mrs Blake hardly knows which of these two to be more disgusted about, but since Wellington sheds, this latter-day Craig’s Wife decides to focus her animosity on the cat. (Surprise!) The social worker, however, warns Mrs Blake that Wellington is vital to Lucy’s mental state and she should at all cost be allowed to keep her pet.

The other occupant of the house is Lucy’s older cousin, Angela. (Another amusing bit of casting, since in the earlier Amicus production, The House That Dripped Blood, Chloe Franks was the one dishing out what she ends up taking here.) Upon seeing Wellington, Angela protests that she was never allowed to have a cat, and makes a bid for audience sympathy (all right, my sympathy) with the following argument:

Mrs Blake: “We let Lucy keep Wellington because she doesn’t have a mummy and daddy—but you do.”

Angela: “If you and daddy were killed in a plane crash, could I have a cat then?”

“Do tell me more about your fascinating theory, Mr Gray…”

But this piece of logical debate proves misleading, as Angela settles into the task of making Lucy’s life miserable, and manages to blame a series of minor household upsets upon Wellington, to whom she takes a dislike after her overtures to him are rejected in no uncertain terms.

So—the two girls are out in an elaborate, self-contained “summer house” (more like a small cottage), painting Wellington’s picture. Lucy runs off to shows hers to her Aunt Joan (why??), and in her absence Angela chases Wellington around, finally knocking a small tin of red paint to the floor in another bit of this film’s Subtle Foreshadowing. Mrs Blake arrives immediately afterwards, prompting, “Look what Wellington did!” from dear little Angela, and a threat to get rid of Wellington from her mother.

Later, a bored Angela discovers by accident that the model planes she builds with her father are distressing to Lucy, for obvious reasons; and an early, hand-held, zoom-zoom piece of harassment has such a gratifying effect upon her cousin that Angela steps up her attack.

Watching from her window one day, Angela sees her father stop briefly to play with Lucy in what is, to our knowledge, the first bit of friendliness she’s been shown since arriving. This, naturally, puts thoughts of brutal revenge into Angela’s mind. When her father has departed, Angela throws open the window and sics a remote-controlled model plane onto Lucy, making it swoop at her again and again as she throws herself to the ground to protect both herself and Wellington. (Another lovely bit of editing: at one point the plane that Angela is supposed to be flying is still sitting on the window-sill in front of her.) Lucy finally makes a run for the house, and makes it inside—just.

I believe this is what they mean when they say that evil is seductive.

At this point Angela loses control of the model plane, and it slams into the side of the house, just next to the door, smashing a window and blowing up. Remarkably, Mr and Mrs Blake hear none of this, Mrs Blake being too taken up with the fact that Lucy’s clothes are dirty from her repeated trips to the ground. On the other hand, the simultaneous fact that her young niece is in a state of extreme emotional distress evidently escapes her attention. Angela, scooting downstairs from her room, announces, “She was playing with her cat and fell in the mud!” This is the final straw for dear Aunt Joan, who as soon as the kids are out of earshot, starts telling her spineless husband of a place where, “They do it quietly and painlessly.”

Well, yes: I’m certainly being convinced by all this that cats are evil. Mind you, I guess I should be grateful that Mrs Blake isn’t advocating doing it loudly and painfully. I wouldn’t put it past her.

Anyway, the next time Lucy’s back is turned, Wellington finds himself in the car, being taken on The Long Last Journey… Lucy, of course, is next seen rushing about calling frantically for her cat. Angela takes it upon herself to break the glad tidings:

“Don’t you know? Wellington’s gone – gone for good! Daddy took him away this morning. He sold him to the butcher – to make into dog meat! Ha, ha, ha, ha, ha!”

And I’m not ashamed to admit that at this point, I took a quick emotion-break and went and cuddled my own cat.

That night, Lucy having cried herself to sleep, Mrs Blake, who is nothing if not thorough, completes the emotional devastation of her niece by silently collecting Lucy’s books on the occult and throwing them onto the fire…along with a photograph of Lucy’s mother.

A wizard Wellington did it!

But as it happens, Mrs Blake missed one book: a much older, leather-bound one with handwritten contents, which Lucy keeps under her pillow. And there it is lying when Lucy is woken by a soft meow…

(Wellington’s return is never actually explained, by the way; apparently we’re meant to infer the means of it from what happens next. Personally, I prefer to believe that the spineless Mr Blake was just spineless enough to stop the car and let him out somewhere, not reckoning on his feline powers of navigation.)

But the joyful reunion is cut short when Lucy realises what the consequences will be if Angela finds out about the prodigal’s return. “What are we going to do?” she wails, to which Wellington responds be hopping onto the bed and pushing his nose under the cover of the leather-bound book…

Angela looks out her window and sees a light in the summer-house. Running out there, she finds Wellington looking on as Lucy finishes drawing a large inverted pentagram on the floor in chalk. Angela predicts trouble “when Mummy gets home”, indicating more botched editing, as we weren’t aware that Mummy was out. Lucy takes no notice, but comments that the ceremony can begin. She tells Angela that she can watch, but that she must not step into the pentagram.

Upon which Angela, with a smug expression, immediately does.

Lucy and Wellington exchange significant looks. Lucy smiles; Wellington purrs.

Lucy chants an incantation, of which only the word “Angela” is recognisable. Growing nervous, Angela tries to bolt, but finds that she cannot leave the circle enclosing the pentagram. And then she starts to shrink…ending up a size one might not inaccurately call “mouse-like”.

It’s only a movie, it’s only a movie…

[*sniff*]

Much use of oversized props and superimposition follows; and it really is remarkable how much worse this is done here than it was in the equivalent scene in The Incredible Shrinking Man – although colour film certainly doesn’t help. To be fair, the “giant” candlestick is rather nice; but the oversized prop paw meant to represent Wellington is just awful.

Angela dodges beneath a couch, hiding behind a fringed throw; and while Lucy’s hand gropes for her from one side, Wellington’s, ahem, “paw” keeps her in play from the other. It turns out that beneath the couch there is a mousetrap baited with cheese (did people do that in 1975? did people ever really do that?), and Angela manages to get her nightgown caught on it.

The film doesn’t go for the quick, gruesome ending, though. Angela escapes from the trap, then uses the pointy end of a stray paintbrush to fight off Wellington, who recoils with blood streaming from an injury not in – phew! – but next to his eye; an effect so fake that not even I can get worked up about it.

Instead, I will shake my head in mystification at the tone of this sequence, which seems to suggest that we’re supposed to be glad about Angela’s (temporary) victory; further proof, if we needed it, that the makers of The Uncanny did not in the least understand their target audience.

“Mummy” arrives home at this juncture (where “Daddy” is, we never learn; perhaps after reprieving Wellington, he figured he’d better keep driving). She, too, sees the lights in the summer-house, and immediately marches in that direction…

Karma.

Angela, meanwhile, having driven off Wellington, makes a fatal tactical error, emerging from under the couch and grovelling to Lucy, claiming that, “I didn’t mean to hurt Wellington! You’re not angry, are you?”

Oh, nooooooo…

Accompanied by ridiculous echo-ey growling noises on the soundtrack, the Fake Paw reappears, and Angela is pinned to the spot by claws through her nightgown. The approaching Mrs Blake then calls out for Angela, and Lucy wraps up this pleasant little interlude by…putting her foot down.

So when Mrs Blake finally enters, all she finds is a smear on the floor that she takes to be more spilled paint. “Ugh! What a sticky mess!” she complains, trying to wipe it up. “Why can’t you be good like Angela? She never puts a foot wrong!”

Boom-tish.

So – again – tell me: how exactly does this segment prove that cats are eee-vil? At worst Wellington is Lucy’s familiar, and so is subject to her commands. My main objection here, though, is that while Angela may have gotten her comeuppance, I’m not convinced that Mrs Blake really did. From what we’ve seen of her, Angela’s “disappearance” probably would have meant nothing more to her than one less person to mess up the house.

Back in the present, Frank Richards objects that children disappear for all sorts of reasons; and, let’s face it, unless Lucy confessed, Gray couldn’t possibly have any evidence of what really happened. Nor would it prove his thesis if he did.

(Yes, that’s exactly right!…but still the film doesn’t seem to realise it is.)

If your cat’s paw looks like this, please, seek medical attention!

The men are interrupted by some hilariously inappropriate yowling meant to signify Sugar’s desire to come in again, and Richards rightly ignores Gray’s panicky demand that he not open the door. However, he does refuse Sugar a saucer of milk—and so he should.

[Community service announcement] DO NOT GIVE YOUR CATS COW’S MILK, PEOPLE!!!!!! [/Community service announcement]

As he watches Sugar slink around, Gray mutters, “We let them wander about, just as they please – hardly noticing them – and all the time, they’re watching us – spying on us – making sure that we behave!”

Pardon me for mentioning it, but on the evidence of this film so far, Homo sapiens could do with something to make it behave.

Richards remarks that if Gray wants his book published, he’s going to have to come up with more convincing evidence than that which he’s provided so far. Hear, hear! “Do you remember the case of Valentine De’ath?” responds Gray, to which Richards replies drily, “It’s difficult to forget it.”

“It was the cat that did it! The cat!” insists Gray.

And here The Uncanny crosses into near-unforgiveable territory. This is, as I’ve indicated (i.e. harped on about endlessly) a very confused film, both philosophically and tonally. It hardly works at all, and only when it takes its premise seriously; and it repeatedly undercuts itself with jokes that aren’t funny.

All the best people like cats.

But as it turns out, we’ve barely begun to scratch the surface of what this film can deliver by way of an unfunny joke. This third segment, played for laughs, is cringe-worthy to the point that not even Donald Pleasence can save it—and in my humble opinion, The Don can save almost anything. (Yes. Even The Pumaman.) This final tale has only one redeeming feature—though frankly, you probably have to be as fundamentally warped as myself to consider it as such.

(We do, however, get one amusing touch here: the photograph of “Valentine De’ath” in Gray’s file is a shot of The Don as Ernst Blofeld…complete with cat.)

We open in Hollywood in 1936, where the actor Valentine De’ath – “V.D.” to his friends – and his wife, Madeleine, are making a horror movie together—and honestly, it’s astonishing that any group of real film-makers could create a film-making pastiche this bad. My suspicion is, they wanted to do a take-off of silent movie-making, à la Singin’ In The Rain (and may Bastet forgive me for mentioning that film in the same breath as this one), only then someone realised they didn’t make this kind of horror movie in the 1920s. So what we end up with is a clumsy melding of the production of something like The Tower Of London with scenes where the actors have music played on the set to create a mood.

There are other problems, but we’ll get to those.

We find Madeleine strapped to a rack, being threatened with torture or worse by her loving husband. De’ath starts a pendulum in motion, commenting, “Parting is such sweet sorrow.” The thing descends at a surprising pace, and Madeleine screams in agony…only to have her disgusted director yell, “Cut!”, complaining that her performance was too melodramatic, and could she please tone it down…?

What, not “A Miracle Picture”? I’m disappointed.

Not really.

We get a tone-setting jump to a shot of the film’s producer snipping of the end of a cigar in a mini-guillotine, as a police detective explains that whole thing seems to be a tragic accident. “Most unfortunate,” he shrugs. Apparently the question of how, exactly, a real, bladed pendulum got substituted for the fake one isn’t worth bothering over, as this scene is the last we see of him.

(Again, this feels like a 20s touch, when MGM, for one, had a private police force whose job was to cover up scandals and destroy evidence.)

The cop also tells the producer that he’s free to resume work on his film as soon as he wants, to which Pomeroy responds by chuckling and gleefully rubbing his hands together. He and the director, Barrington, are discussing what to do about their lack of a leading lady when De’ath wanders in. (Donald Pleasence is done up here to look rather like Lionel Atwill; his exceedingly obvious toupée – which he wears even under his costume wig – is another nice touch.) He’s not put out by the debate; on the contrary, he has something to contribute to it. He takes the other two out onto the set and introduces them to Edina Hamilton, Madeleine’s stand-in. (I presume he means previously Madeleine’s stand-in, as neither Pomeroy nor Barrington know her.) They agree she looks remarkably like “a young Madeleine”, and hire her when De’ath makes the point that given the resemblance, they may not need to do any re-shoots at all.

Later, at the House Of De’ath, the secret lovers celebrate the success of their wicked scheme. (They’re not cats, so it can’t be eee-vil.) “What do you suppose the neighbours would say,” De’ath remarks, taking Edina into his arms, “if they knew I had brought a beautiful woman to my house on the very day that my wife was killed?”

“Oh, man… Ray and Pete were right about this film.”

Yes, that’s right, folks: (1) Madeleine’s death, (2) the police “investigation”, and (3) Edina’s casting all took place on the same day.

Suddenly, Edina squeals at the sight of Madeleine’s ginger and white cat (which has, of course, overheard the lovers’ conversation). Quoth Edina:

“I thought I saw a pussy cat! I did! I did!”

As Edina tosses the poor thing around, De’ath explains, “He’s Madeleine’s. A vain, empty-headed creature like his mistress,” and that he calls it, “Scat” – as in, “SCAT!!”

“It’s the cat-gut factory for you tomorrow!” he announces cheerfully, as an off-screen Scat yowls and spits.

Actually…there’s far worse in store than the cat-gut factory…

Later, after Edina has tried on Madeleine’s clothes, and while she lies on Madeleine’s bed with Madeleine’s husband, the two of them making bad jokes about Madeleine’s grisly demise – “She went all to pieces!” “And now she’s just a bit player!” – the lovers are disturbed by a loud yowling sound. They track it to its source, and find that Scat has given birth to a litter of kittens.

Uhhh…

Are we quite sure we couldn’t find anyone less our own size to pick on?

Okay. I guess I can accept that De’ath didn’t know what gender his wife’s cat was—although the fact remains that, for complicated genetic reasons I won’t get into here, the vast majority of ginger cats are male. (Maybe this one had a sex-change, like Spot?) But when Edina was holding it up in the air, that cat was definitely not pregnant.

But this is the least of our worries. Without hesitation, De’ath walks across the room and tries to pick up the basket of kittens. Scat scratches him once, but he secures the basket on the second attempt—and having done so, De’ath carries the newborns out and flushes them down the toilet; a scene placed in a context of slapstick chases and waah-waah-waaahh noises on the soundtrack. Because violence against cats is funny—right?

Remind me again who the bad guys in this film are?

By this stage, I’m sure you don’t need me to tell you that Scat subsequently takes a gruesome revenge upon De’ath and Edina—although not gruesome enough, not nearly gruesome enough—and quite unintentionally, I’m sure, The Uncanny manages to place itself in a very rare subset of killer animal films.

Indeed—I had cause only recently to discuss the year 1977 in film-making; one of its negative highlights being Orca, in which, driven mad by the killing of his wife and child, the titular animal manages to contrive (among other things) the complete destruction of an oil refinery. Imagine my surprise, then, when in The Uncanny I found a second film released in 1977 that involved an animal talking revenge upon the humans that wronged it via a startling understanding of engineering and physics.

That’s right, folks—from this point on, it’s Death Wish VIII: The Kittening.

“How dumb do they think I am?”

The next day, at the studio, while De’ath films a sword-fighting scene, and Edina reads a comic-book, we see Scat slinking along in the rafters. She positions herself by the rope holding up one of the heavy lights, and starts to chew…

(Ignore the fact that it would take a cat about ten years to chew through a rope that thick; notice instead the cat-food smeared on it to encourage her to try.)

During this sequence, Edina’s scream – “Eeeeeee!” – which we’ve heard once already, becomes a running-joke. (Which wouldn’t have worked in a silent film context, so there’s that.) A nosy stage-hand notices the imminent fall of the lamp just at the critical moment, and shouts out a warning to De’ath as Edina screams – “Eeeeeee!”

De’ath and Edina stare upwards at Scat, while the director demands, “What idiot fixed that lamp, anyway?” I dunno, the same idiot who fixed your pendulum?

A weary De’ath and Edina arrive home at find Scat there ahead of them. For some reason, they are far more taken aback by Scat’s ability to get from the studio to the house, than they seemed to be by her ability to get from the house to the studio. Upstairs, they find their bed completely shredded. “How are we going to catch it?” frets Edwina, to which De’ath replies, “What was it that killed the cat?”

That would be you, you son of a bitch.

Oh, I’m sorry. It seems the correct answer is, “Curiosity.” An extended chase scene follows, to the accompaniment of Keystone Cops-esque music. Spare me. The cat is not caught. That’s all that matters.

Revenge is a dish best served cold, with mince smeared on it.

As De’ath and Edina leave the next morning for the studio, we cut inside to find Scat contemplating – but not touching – a series of baited traps: box-traps, bear-traps, poisoned food… Fortunately, De’ath left the bottle of poison – helpfully labelled “POISON” – sitting on a cabinet where Scat can see it.

That’s right. They can read.

At the studio, Edina is struggling with a scene in which she is required to scream in terror as the doors of an iron maiden-like contraption – except the budget only extended to wood – close upon her. As usual, she can manage only, “Eeeeeee!” More interestingly, we learn that while the wooden maiden has a back panel by which the actor can slip out of the box, it can be locked; and that the cable by which the front door is operated must be tightly held, otherwise the door will slam shut.

I am no longer surprised by the lack of reaction to the real pendulum. Obviously, at this studio death-traps are a way of life. So to speak.

Barrington gives up on trying to get a real scream out of Edina. De’ath intervenes, and persuades him to let them do their love scene instead. Even this Edina can’t get quite right…and although she does finally manage a genuine scream of terror.

“The cat! I saw the cat!” she explains, but De’ath thinks she’s seeing things, Scat being safely boxed / impaled / poisoned by now.

After this double-disaster, Pomeroy and Barrington are getting nervous about their leading lady. (Angry as this sequence makes me, I must give props to Samantha Eggar for being game enough to take on the thin-ice-ish proposition of playing a bad actress.) De’ath promises that the two of them will stay behind at the studio that night, and rehearse…and rehearse…and rehearse…

“So, let’s see: if Force = Mass x Acceleration…”

Scat, sitting up in the rafters, takes all this in with great interest, as indeed she does the design of the wooden maiden; almost as great an interest as that with which we subsequently watch her slinking down to the device and locking its back doors.

Seriously.

After some persuasion of the reluctant Edina, she and De’ath go back to the sound-stage to rehearse the wooden-maiden scene, though at first Edina can only produce that idiotic, “Eeeeeee!” An exasperated De’ath offers to show her how it’s done. They exchange places, De’ath reminding her to hold the cable tight, “Or else, I shall be killed.”

Of course you will.

They go through the scene, De’ath producing a series of enthusiastic screams. They swap places again, and as Edina stands within the wooden maiden, preparing, we assume, to let fly with one more, “Eeeeeee!”…she looks up and sees Scat…

“Perfect!” beams De’ath as Edina screams bloody murder; or at least bloody vengeance.

At the same moment, Scat jumps down onto De’ath’s head—the shock of which makes him let go of the cable…

As De’ath is investigating the resulting mess, a low yowling sound reaches his ears. De’ath arms himself with an axe from the set – a real axe, it goes without saying – and the final chase begins…

I’m astonished that Robert Bloch didn’t sue.

The next morning, Pomeroy arrives early at the studio to see how the rehearsal went. The door he closes behind himself has dramatic splashes of blood across it, but he doesn’t notice. He calls out for De’ath, asking how the rehearsing went and, when he gets no reply, chuckles, “What’s the matter, cat got your tongue?”

And then he sees that De’ath is dead, and bloody-mouthed…and that nearby, Scat is chewing on a hunk of…something…

Back in the present, Richards is yet again objecting that Gray has no actual proof. Gray responds by handing him his big bundle of papers, presumably describing many more than these three stories – and, we hope, more convincing ones.

“It’s here – years of research,” he insists breathlessly. “Evidence from all over the world, proving beyond a shadow of a doubt that cats have been exploiting mankind for centuries! We think we’re the masters and they’re merely pets, but we’re wrong. They’re the masters!”

You say that like it’s a bad thing.

“But someday – someday,” concludes Gray threateningly. He is interrupted by angry growling, supposedly from Sugar, whose visual shows us the world’s most placidly happy cat. A remarkably patient Richards promises to read through Gray’s evidence, which Gray insists he must guard with his life.

“Yes, master…”

Richards shows Gray out. As he dons his coat, Gray comments, “It’s a strange thing: years ago, people used to believe that a cat was the devil in disguise. I’m beginning to think they were right.”

Oh, yeah? Well, years before that, other people worshipped cats as gods. And I’ve always thought they were right.

Having finally gotten rid of Gray, with a long sigh of relief, Richards returns to his living-room, where he finds Gray’s bundle now on its side, and open…and Sugar sitting on top of it. Richards displaces him, and sits down to some reading.

Gray scurries through the streets, rightly suspecting that forces are massing against him. They catch up with him on a set of stone stairs, attacking from all sides. The usual mixture of dubbing, cat-tossing and stunt-person thrashing follows, and Gray finally plunges down the stairs, lying motionless at their foot. In an effective touch, his fogged breath is abruptly cut off…

(The cats in this scene are in a great deal more danger than most of this film’s humans: the stuntman standing in for Peter Cushing nearly squashes two of them as he rolls down the stairs!)

AND SO SHALL PERISH ALL CAT-HATERS!!…even if they are Peter Cushing…

Meanwhile, Richards’ reading is disturbed by…something. He glances up, looking around uneasily—and suddenly, we’re seeing Sugar through the flames in the fireplace, if you please. Richards looks up again, blinking as some much more powerful force begins to control his puny human brain.

Richards re-folds the paper he was reading a returns it to Gray’s bundle, which he then picks up and throws into the fire; and as it burns, he trots off obediently to get Sugar a saucer of milk…

NOOOOOO!!!!

It is a horror movie, after all!

“Feed me! Cuddle me! Open the door!” Some mystery.

Footnote: God bless the Italians…

♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦

The B-Masters’ take a look at some actors who have gone from the sublime to the ridiculous…

A much better cat-revenge movie (which I’ve mentioned before) is the Shadow of the Cat. I was rooting for the cat throughout the movie.

LikeLike

I’d be appalled to think that anyone was not!

LikeLike

Ah, one of my favorites from the older site. This film fits well into the category of films I won’t bother watching because the mere premise is too stupid even for me. Which is saying quite a bit considering some of the stuff I will cheerfully put myself through. Not often you can put Peter Cushing and Donald Pleasence in the same film and not have my attention but there you go. It reminds me of the Gene Siskel quote “Is this film more interesting than a film of the same actors having lunch”.

It occurs to me a better version of this film would just have the three main actors talking about their careers while crumpling up pages of the script and tossing them into a garbage can on the other side of the room while making mildly unkind remarks about the ability of the screenwriter. Make it so Cushing has the relative shot consistency of Michael Jordan and have Milland mutter “uncanny” under his breath and you have a much more compelling movie in my view.

The 70’s yielded stranger things than that, believe me.

LikeLike

The third story sounds an awful lot like one by Bram Stoker, I think called “The Iron Maiden.”

As for cats, I love them, but I understand how others might be unnerved by them. The little fuzzers clearly appreciate that our civilization has given them a very comfortable existence, but unlike dogs, they never really seem to become part of that civilization. They’re like Bill Murray in Ghostbusters–they’re not in the world, they’re alongside and (in the cat’s case) above the world, jabbing it in the ribs every chance they get.

LikeLike

“The Squaw.” And you’re right, except the cat’s vengeance is even more well-deserved in that story. I wasn’t happy with the last couple of sentences, though, even though I’m sure I was supposed to be.

LikeLike

By the way, one excellent cat actor was Orangey, who was in the mentioned Incredible Shrinking Man, but also in Breakfast at Tiffany’s, This Island Earth, “Batman” and a number of others.

LikeLike

He was the cat who starred in Rhubarb, and appeared under that name in a few other films too, most notably The Comedy Of Terrors. He was also in Village Of The Giants, though unbilled.

LikeLike

My favorite cat quote is a poke at flat earthers:

Of course the world can’t be flat. If it was cat’s would have pushed everything over the edge by now.

As for cats being not really in our world, but alongside it. I think of Constantine and how cats are the conduit between Earth and Hell.

LikeLike

Earth and where!? Hmmph!!

LikeLike

I saw this movie on TV as a kid, as part of a “monster week” series on a local channel. There was no internet then (it must have been like 80 or 81) and the TV listings on showed the title so I had no idea what it was about. I remember being pretty disappointed that the “monsters” were cats, although probably not nearly as disappointed as the people who bought tickets based on that Italian poster!

LikeLike

Alleged monsters, you mean… 🙂

It’s wonderful to think that people were still trying to sucker people in via outrageously inaccurate poster art as late as this…though of course it was soon to give way to outrageously inaccurate video-box art…

LikeLike

I came across another great cat quote, from Blackadder IV. “Just how did you get all that custard out of such a small cat?”

(If you’re easily grossed out, don’t look it up)

LikeLike

Don’t worry, I wasn’t going to!

LikeLike

Very belated comment, but UGH, forewarned is forearmed, and I shall know never to watch this horrible bit of muck. I hate any films that include cruelty to animals, but ones about cruelty to cats are totally beyond the pale. Even nasty jokes about cats put me right off the characters and the whole program (there was an episode of New Tricks like this, it was the pits in a series I otherwise enjoyed a lot). Sounds like The Uncanny should have been rewritten entirely to make the cats the heroes, which frankly they seem to be despite the way it was done. And drowning newborn kittens played for laughs??? Lock up whichever sociopath came up with that idea. Maybe that’s it – their target audience was sociopaths.

I thought I read once that Peter Cushing liked cats, in real life. I can only presume either I imagined that, or he was desperately hard-up when he accepted this role …

LikeLike

Peter Cushing was a professional actor. I’m sure he had to appear in a lot of things that he found personally repugnant.

LikeLike

Yes, the notion that violence against cats is somehow funny is depressingly pervasive. 😦

It’s all overtly faked or offscreen here, and as I say, you can tell from the cats’ demeanour than they weren’t actually being mistreated; but the whole thing is just bizarrely wrongheaded and confusing.

LikeLike

I remember Simon Williams as one of the survivors (minus a hand) in Tigon’s THE BLOOD ON SATAN’S CLAW, whose assaulted fiancee (Tamara Ustinov) is taken away to Bedlam with a claw in place of her hand.

LikeLike

I just watched MANIAC, and it had a great quote. The mad actor masquerading as the mad doctor tells a neighbor, “I would never experiment on cats. I have too much respect for Satan.”

LikeLike

MANIAC has the greatest line in cinema history

“To my notion, those that monkeys with what they got no business to get queer sooner or later.”

LikeLike

As commented above, the “Hollywood 1936” segment is based on Bram Stoker’s short story “the Squaw”, except the story ends with the cat causing the iron maiden to slam shut. There was an adaption of the story in comic art form in Creepy Magazine 13 from Feb 1967, adapted by Archie Goodwin and drawn by Reed Crandall. In the grand tradition of horror hosts making a pun at the end of the story they are presenting, “Uncle Creepy” says “…cat got your tongue?” in the final panel. So the writers of the Uncanny lifted the last scene with Donald Pleasence and John Vernon from THAT version of the story. Goodwin should have sued them for not giving him credit.

LikeLike

I recall having a bit of a discussion about The Squaw as it relates to this film on the B-Masters Cabal site, but all the comments there on this film there seem to have disappeared.

LikeLike