“That bunch of Scraps has caused all our trouble!”

Director: J. Farrell MacDonald

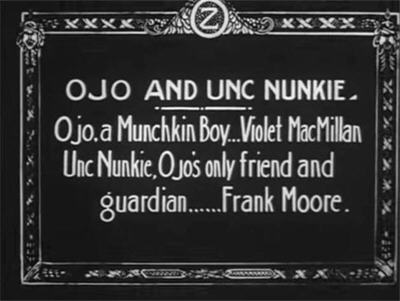

Starring: Violet MacMillan, Pierre Couderc, Raymond Russell, Bobbie Gould, Frank Moore, Leontine Dranet, Marie Wayne, Richard Rosson, Fred Woodward

Screenplay: L. Frank Baum, based upon his novel

Synopsis: Ojo (Violet MacMillan), a Munchkin boy, and his guardian, Unc Nunkie (Frank Moore), are starving because the bread-tree in their yard is no longing supplying them with food. Ojo tries to persuade Unc that there is plenty of food in the Emerald City, but he is too tired and hungry to make the effort, until persuaded by Ojo’s despairing sobs. Meanwhile, Margolotte Pipt (Leontine Dranet) bemoans the fact that her husband, the magician Dr Pipt (Raymond Russell), has spent six years working on his Powder of Life. Margolotte begs her husband to hurry up and finish, so that she may make herself a servant, and not have to do any more housework. Climbing into her attic, Margolotte begins to fashion her new servant out of an old patchwork quilt. Outside, the Pipts’ daughter, Jesseva (Bobbie Gould), becomes engaged to her sweetheart, Danx (Richard Rosson). They join their friends and dance in celebration. On the road, Ojo and Unc find their way blocked by Mewel (Fred Woodward), a mule. When they succeed in passing him, they join the Munchkins’ dance, as does Mewel. Margolotte, picking up a wand, tries some magic herself: to her delight, the quilt pieces she has shaped join themselves together into the form of a girl. At Jesseva’s prompting, Margolotte invites Ojo and Unc into the house. Ojo is fascinated to hear Margolotte’s plan for the Patchwork Girl, but horrified when he learns that the new servant will be given no brains. Cautiously, Ojo searches the room and finds some of Dr Pipt’s magic potions. He mixes a formula consisting of a lot of Cleverness and Ingenuity, some Judgement, and just a smidgeon of Obedience and, unobserved, slips it into the Patchwork Girl. Soon afterwards, the Magic Powder of Life is finally ready. Dr Pipt uses it to bring the Patchwork Girl (Pierre Couderc) to life, but gets more than he bargained for when her energetic cavorting knocks a vial of Petrifaction Liquid over Margolotte, Danx and Unc Nunkie, turning them into statues. Initially, Dr Pipt, Jesseva and Ojo are in despair, as Dr Pipt comments that it will take another six years to make more Powder of Life; but then the magician finds in one of his books a spell for reversing petrifaction. He declares that he will find the necessary Dark Well and collect its waters, while Ojo and Jesseva, along with the Patchwork Girl, must search for a six-leaf clover and three hairs from the tail of a creature known as the Woozy. Jesseva begs her father to reduce Danx to only six inches high, so that she can carry him with her. This done, the four set out upon their quest…

Comments: In 1914, L. Frank Baum and his family relocated to California. One of Baum’s interests there was his membership of an organisation that called itself (courtesy of the man himself) “The Lofty and Exalted Order of Uplifters”. This was an offshoot of the Los Angeles Athletic Club, founded by ex-Chicago plumbing tycoon Harry Marsten Haldeman (the grandfather of Richard Nixon’s Chief of Staff, H.R. Haldeman) with the declared intention of, “Uplifting art, promoting good fellowship and building closer acquaintance”; a noble-sounding manifesto somewhat undercut by its sub-motto – also composed by Baum – which added that, “Nothing has been found more uplifting than a cocktail, except perhaps several.” In a wonderful piece of seeming contradiction, Baum and Haldeman joined with fellow “Uplifters” Clarence Rundel and the composer Louis F. Gottschalk to form The Oz Film Manufacturing Company, their aim being, “To produce quality, family-oriented entertainment suitable for children.”

While it was not the company’s intention to produce only Oz films, Baum’s tales were the obvious place to start. The company’s directors set up shop in a small studio on Santa Monica Boulevard, and also arranged for access to San Diego’s Balboa Park for their location shooting. Their facilities in place, the team set about assembling a crew of actors and technicians; while Baum also wrote the company’s first screenplay, an adaptation of his 1913 novel, The Patchwork Girl Of Oz.

The techniques and conventions of film-making had made huge strides in the years since 1910, when Frank Baum’s stories had last been adapted for the screen. The Patchwork Girl Of Oz, unlike its Selig Polyscope predecessors, was a feature-length production running over eighty minutes—at least at the time of its first release. Sadly, this film is one of the many casualties of the silent era, existing today only in a truncated version of around an hour long, these cut prints being found in Britain some years after the film had been declared lost altogether.

The impact of these cuts is felt most in the second half of the film, which now contains several unconnected and seemingly pointless episodes that presumably made more sense in the original release. The contemporary difficulties caused by this situation are exacerbated by the fact that The Patchwork Girl Of Oz contains minimal, and minimally informative, intertitles, usually no more than a bald statement of who a new character is, and who plays them, which offer little assistance to the viewer trying to interpret these episodes correctly.

However, other of the film’s shortcomings can be blamed upon no-one but its makers. The language of film was still evolving in 1914, and styles of film-making varied wildly. Even so, and allowing that the film was intended for children, The Patchwork Girl Of Oz too often exhibits the exaggerated yet simplistic style of a stage pantomime; the actors mug wildly and wave their arms around to convey every possible emotion. In this, the film bears too much of a resemblance to The Wonderful Wizard Of Oz. Also like its predecessor, it insists upon each frame being filled with movement—as opposed to action. I suggested that a viewing of The Wonderful Wizard Of Oz required a tolerance for pantomime; what’s needed here is a positive passion for capering. Rarely has a film expended so much energy to so little purpose.

Another indication that Baum and his collaborators were still thinking in terms of stage conventions is the fact that the film’s nominal hero, Ojo, is played by a girl. It is, of course, common practice in pantomime to have boys’ roles filled by girls; The Patchwork Girl Of Oz takes this step while making not the slightest effort to disguise or deny the gender of its star, or to acknowledge the difference between the perspectives of the stage audience and the film audience.

With her flowing blonde curls, her pouting, her skipping, her hand-clasping, her eyelash-fluttering and her flirting with the camera, Violet MacMillan gives us an Ojo who makes Little Lord Fauntleroy look like Arnold Schwarzenegger. Suspension of disbelief is out of the question. Hilariously, Miss MacMillan’s performance seems finally to have confused even Ojo’s own creator: while an early title card declares Ojo to be “a Munchkin boy” – and thank heavens, because we’d never have figured it out otherwise – another card late in the film refers to Ojo as “that girl”!

He’s a boy. Honest.

This is not the only piece of cross-gender casting to be found in The Patchwork Girl Of Oz. Baum was unable to find a female performer quite up to the capering challenge presented by playing the Patchwork Girl, and instead cast Pierre Couderc – “The Marvellous Couderc” – a French actor, screenwriter and acrobat. Since the role of Scraps, the Patchwork Girl, required Couderc to be completely made up throughout the film, this piece of gender-impersonation is infinitely less jarring than Violet MacMillan’s contribution; although the knowledge that Scraps is played by a man does lend a certain edge to the scenes late in the film when the Scarecrow, encountering someone as physically uncoordinated as himself for the first time in his life, is instantly romantically smitten.

The main problem with The Patchwork Girl Of Oz, however, is simply that none of the characters are particularly likeable. Scraps herself is downright annoying. Ojo comes across as a selfish narcissist: when their bread-tree runs dry, Ojo first emotionally, then physically bullies his ill, elderly guardian into walking to the Emerald City with him in search of food. (Try watching this sequence and not yelling, “Get a job, ya bum!”) Dr Pipt and his wife have devoted six years to the creation of the Powder of Life chiefly, we gather, because Mrs Pipt doesn’t want to do housework (okay, I have some sympathy with that); while Mrs Pipt plans to deny Scraps brains because, “The fewer brains, the better servant.”

A subplot involves the instant longing of every female who sees it for the tiny statue of Danx, particularly Jinjur, “a maid of the Emerald City”, leading to her endless attempts to steal it via a series of physical tussles that grow increasingly tiresome; and, failing that, to her revenging herself by getting the protagonists arrested by the Emerald City Guard (for environmental vandalism, no less). Meanwhile, Mewel the mule tries to kick everyone who comes near him.

It’s the Marvellous Land of Gender Confusion!

But thankfully, there are some positives in The Patchwork Girl Of Oz, most notably the charming surprise of two separate sequences of stop motion—a year before one of the technique’s two most famous exponents, Willis O’Brien, used it for the first time, in the short film The Dinosaur And The Missing Link. Its first use here occurs when Mrs Pipt – for all her hatred of housework – makes the various pieces that will be Scraps out of an old patchwork quilt; instead of sewing them together, she borrows her husband’s magic wand and makes the pieces assemble themselves. Later, when on his quest for the Dark Well, Dr Pipt comes across a mysterious house in the woods that at first seems empty, but which, when he steps outside, prepares a bed for him. Later, while he sleeps, the house’s furniture again comes to life and obligingly sets the table and cooks a hot meal.

The film’s other highlight comes in the shape – or misshape – of the Woozy, a creature so entirely peculiar and inept that it instantly won my heart.

The Patchwork Girl Of Oz starts with Ojo and Unc Nunkie on their quest for a free lunch. We then detour into the betrothal of Jesseva and Danx, and I should perhaps say a few words here on the subject of Munchkins. In the novels, the Munchkins were only slightly shorter than other people, and Baum himself never made much of it; neither does he here. Munchkins as “little people” is entirely the invention of later screenwriters.

After Ojo and Unc manage to circumvent the threat of Mewel the mule – whose addiction to butt-scratching is truly disturbing – they fall in with the celebrations over Jesseva and Danx’s betrothal, before being invited into the home of the Pipts; a gesture their hosts will live to regret.

Call it ‘magic’ all you like: if it comes with a flask, it is by definition SCIENCE!!

Ojo, in the course of poking and prying, comes across Dr Pipt’s supply of “Magic Brains”, and mixes a potion that he slips into the head of the as-yet inanimate Patchwork Girl. This action coincides with the culmination of Dr Pipt’s six years of labour, and he triumphantly declares the Magic Powder of Life complete. He prepares to bring Scraps to life, and—

—there’s a chunk of the film missing, although we can easily infer what happens: Scraps, starting as she means to continue, begins to caper wildly, and in doing so spills onto Margolotte Pipt, Danx the Munchkin and Unc Nunkie a Liquid of Petrifaction; they are instantly statue-ified. As the oblivious Scraps continues to caper inside and outside of the house, the three bereaved parties bewail the situation. However, Dr Pipt declares himself just too tired to devote another six years to making more Powder of Life.

(Wait, he only made enough for one dose? Jackass.)

But then a thought occurs to him, and in one of his books of magic Pipt finds a spell for reversing petrifaction: one requiring waters from a Dark Well, a six-leaf clover, and three hairs from the tail of a creature called a Woozy. Jesseva has her father shrink the petrified Danx to a transportable size, so that she can carry him with her; and while Dr Pipt goes in search of a Dark Well, the girls, accompanied by some of Jesseva’s Muchkin friends, set out to find the clover and a Woozy.

Get used to this, folks…

The latter task proves rather absurdly easy, as there turns out to be one corralled about twenty yards from the Pipts’ front door. Scraps climbs into the enclosure to flush the Woozy out of its cave, and we get our first good look at the legendary beast; and, well, awwwwww…

Scraps invites the Woozy to join her in some capering, then reveals their need for the creature’s tail-hairs. The Woozy is amenable, but pulling them out proves beyond Scraps’ physical powers.

The questers decide that the Woozy must come along with them, but the only way the creature can escape its enclosure is if Scraps succeeds in making it so angry, its eyes will flash fire and burn a hole through the fence. Needless to say, this task proves well within Scraps’ capacity, although you may or may not be surprised to learn that it involves an old-fashioned eye-boink.

Once the Woozy is free, everyone gathers around to hug and caress it, and rightly so. Ojo asks to make another attempt on the tail-hairs, and the Woozy obliges by clinging to a tree while Ojo tugs away, however to no more avail than Scraps’ efforts. The travellers all go on their way and are spotted by Jinjur. She is at first obliging, guiding the travellers through the Wall of Optical Illusion – it isn’t really there – but then she gets a look at the statue of Danx and becomes instantly obsessed with gaining possession of it.

Awww… Woozy!

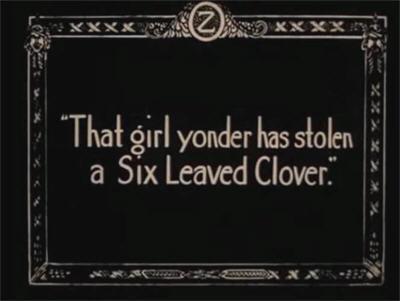

Jinjur’s other contribution at this point is to warn Ojo that plucking a six-leaf clover is against the law in Oz, and to drag him away from the specimen he is trying to collect. Ojo later sneaks back anyway and picks the clover, and Jinjur rats him out to the Soldier With The Green Whiskers (aka Omby Amby, as I recall). Ojo and his companions are threatened with arrest, and Jinjur takes advantage of the situation to accuse them of having stolen the statue of Danx from her in the first place.

A great deal of confusion and capering follows, as Jinjur runs away with her prize and Scraps pursues her, both of them knocking over more innocent bystanders on the way than you would believe possible.

(These chases scenes persist almost to the end of the film, with first one of them in possession of the statue, then the other; while at times other female Oz-ites will intervene, fighting both Scraps and Jinjur and amongst themselves to obtain it—until it becomes difficult not to interpret the desperation of all these women to obtain this hard, six-inch-long object as an obscure dirty joke…)

Meanwhile, finding himself besieged by Munchkins, the Soldier With The Green Whiskers has the Great Alarm Bell rung, which turns out the Emerald City’s all-girl garrison: Frank Baum’s dream chorus-line. Those innocent bystanders, still dusting themselves off, are naturally pleased to see the soldiers on the job, and wave and cheer. The Munchkins find themselves arrested and jailed in short order, as well as clad in prison clothes—which happen to be ghost-costume-like floor-length robes, with eye-holes.

In the Emerald City, Ojo seemed positively macho.

Scraps eventually reclaims Danx from Jinjur, and while capering back through the city, sees her friends being escorted through the streets, but does not recognise them in their robes—not even the Woozy. She slips out of the Emerald City with Jinjur still in pursuit.

Meanwhile, Dr Pipt has come across the House of Magic, and we take a welcome break from all the capering. Instead—

Dr Pipt has been referred to as “the crooked magician”, and now we are given a good look at the reason why. This title is not a reference to his morals, but to his inability to control his legs—making him this film’s third constantly-flailing-wildly character. Worse than this, however, is the specific nature of the doctor’s physical affliction: with his overstuffed jodhpurs, incredibly knobbly knees and peculiar leg action, it is difficult these days not to look upon Dr Pipt as the lineal ancestor of a certain infamous movie character of some five decades later…

The House of Magic is empty when Dr Pipt first enters it, so upon his return he is understandably delighted to discover that it has rearranged itself for his comfort and convenience. The magician is more than a little surprised to find a bed waiting invitingly for him upon his return, but, nothing loath, lies down and goes to sleep. Behind his dozing back, a buffet moves forward and disgorges its load of dinnerware, which arranges itself neatly on the table, and then prepares a hot supper for him.

Just a passing family resemblance…

We now move into the edited-into-unintelligibility section of The Patchwork Girl Of Oz, featuring such puzzling characters as The Lonesome Zoop, and someone else who isn’t even given a name. More pursuit ensues. Mewel then comes wandering back into the proceedings, and the Zoop pursues him.

Maybe the Zoop wouldn’t be so lonesome if it just stopped bothering everyone.

Dr Pipt has set out again on his quest, and comes across a sign for Hoppertown, where only hoppers are allowed. So he hops. This isn’t good enough for the Hoppers, who condemn him to have one leg cut off. Fortunately for the doctor, Scraps’ caperings have taken her in the same direction, and she offers herself as a substitute. This self-sacrificing gesture allows Scraps and Pipt to make up over that whole turning-your-wife-into-a-statue thing, and once clear of Hoppertown, Pipt uses his magic to reattach Scraps’ severed limb. The two of them then stumble across a village of “Jolly Hottentots”, who are, shall we say, somewhat obviously interpreted.

(This part of existing prints is heavily damaged: I suspect it’s been cut out and put back in, maybe several times.)

Their third stop is with a people known as the Horners, who do indeed have horns; but who also one and all carry around what to my dismayed eyes look like the world’s worst boob-jobs. Be that as it may, the Horners have a Dark Well, that is, a well untouched by light; and they allow Dr Pipt and Scraps down into the cavern to collect the waters they need.

The wildlife of Oz had a few…idiosyncrasies.

Meanwhile, Ojo & Co. are being taken before Ozma – installed as rightful ruler of Oz a few novels earlier– for judgement over Ojo’s picking of the clover. (Ozma has a swimming-pool in her throne-room: how enlightened!) The Wizard is also there, acting as Ozma’s Prime Minister. The prisoners are disrobed – so to speak – and Ozma summons the Royal Jury.

This collection of learned citizens not only includes the Scarecrow and the Tin Woodman, but another Hottentot; a Hottentot well worth noticing, as beneath the blackface – well, black everything – is none other than Harold Lloyd! What’s more, another of the earlier “Jolly Hottentots” is played by producer-director Hal Roach; it was on the set of this film that Roach and Lloyd first met, leading to one of the classic collaborations of the silent era.

In the middle of the jury’s deliberation, the Scarecrow slips away for some aimless capering, and then claps eyes on Scraps, hurrying towards the throne-room with Dr Pipt. Naturally, it is love at first sight for both of them.

Dr Pipt bursts into the throne-room and declares his success in gathering the Dark Waters to Ojo, who immediately wrestles the incriminating clover away from the jury, as Pipt tries to pull hairs from the Woozy’s tail. The two of them are abruptly called to order, and throw themselves on Ozma’s mercy, trying to explain their dilemma.

Though Oz was committed to an adversarial court system, constructing ‘a jury of your peers’ presented certain difficulties…

Ozma asks the Wizard for advice, and he suggests allowing Pipt to prove his story by restoring the statues. Ozma orders the statues brought to her presence, and the Wizard obliges by summoning up the petrified Mrs Pipt and Unc Nunkie. Then, just as Dr Pipt is explaining that the third one is missing, Jinjur rushes into the throne-room waving the statue of Danx around triumphantly for no readily apparent reason. Dr Pipt promptly relieves her of it, and Jinjur is arrested for theft. And for being a pain in the butt, which is a much more serious offence. (Not that I’m endorsing the cool crime of robbery, you understand.)

The Scarecrow and Scraps wander back to the throne-room arm in arm, kissing and cuddling; and we get one of the few actually amusing instances of capering in the film as, with eyes only for each other, the two of them trip up the palace stairs. Inside, Dr Pipt is working on his formula, having finally succeeded in pulling those three hairs from the Woozy’s tail. He uses it on the statues and, hey presto! – except that Danx is still only a few inches tall. That’s easily rectified, though; and our story ends with mass celebrations as our various parties are reunited with their loved ones.

The Patchwork Girl Of Oz is too often tiresome rather than entertaining. Its characters are unsympathetic, and too much of its action is repetitive and frustratingly pointless, which makes it difficult to care about the central quest. Of all the myriad capering, only the late scenes between Scraps and the Scarecrow come off as they should, being both charming and funny. Of course, some allowance must be made for the film being incomplete; and it does have its bright spots, notably the Woozy, and the various special effects sequences. Apart from the scenes already described, and the shrinking and embiggening of Danx, these include visual tricks such as the fading into existence of the ringer of the Great Alarm Bell, the characters passing through the Optical Wall, and later reaching the Dark Well of the Horners by walking up and over a fence.

A match made in vestibular disorder heaven.

The film has its subsidiary points of interest, too. Hidden in the supporting cast, alongside Harold Lloyd and Hal Roach, we also find Bert Glennon, three-time Academy Award nominee for his cinematography, and for many years John Ford’s DP of choice. All that means little here, however, where he is none other than the Patchwork Girl’s inamorata, the Scarecrow! Meanwhile, in an odd coincidence, Danx is played by Richard Rosson, the brother of Hal Rosson, the cinematographer of the 1939 version of The Wizard Of Oz.

In addition, the film was directed – although certainly under Frank Baum’s close supervision – by J. Farrell MacDonald, far better know as a long-time character actor (usually playing policemen, a thankless task at Warners), and later as a member of Preston Sturges’ stock company.

Finally, and most (?) importantly, all of the panto-animals in the film are played by Fred Woodward, who graduated to the role(s) from the original company of the stage version of The Wizard Of Oz, where he performed a similar function.

The Patchwork Girl Of Oz was not well-received at the time of its release. Critics appreciated its intentions, but bemoaned its execution. There is, of course, all the difference in the world between a film for children and a childish film – the greatest children’s films are not in the least childish – and it was agreed by the critics and the public alike that The Oz Film Manufacturing Company’s first venture had come down on the wrong side of the fence. The film was not a financial success; and Paramount, which had distributed it, baulked at handling its intended sequels. This was a major blow for Frank Baum and his collaborators, who had been so certain of success that they already had a second film in the can and ready to go: The Magic Cloak.

At least they were right about Fred Woodward.

This is a very transitional time in fantasy: 1910 has Nesbit’s The Magic City, which while still being primarily a story for children has a small amount to offer adults too. In the 1920s you get Weird Tales and increasingly the idea that fantasy could be written for adults, and needs to have a plot rather than a series of events.

LikeLike

These films are a lot more childish than the books they’re based on. (Sadly, “wholesome” usually does translate to “dumbed down”.)

LikeLike