“It’s unscientific, unexplainable, unnatural, unreasonable. It doesn’t make sense!”

Director: Ōbayashi Nobuhiko

Starring: Ikegami Kimiko, Oba Kumiko, Jinbo Miki, Matsubara Ai, Tanaka Eriko, Miyako Masayo, Satô Mieko, Minamida Yōko, Wanibuchi Haruko, Sasazawa Saho, Ozaki Kiyohiko, Kobayashi Asei

Screenplay: Katsura Chiho, based upon a story by Ōbayashi Chigumi

Synopsis: As their vacation time draws near, seven young schoolfriends discuss their plans: six of them – Fantasy (Oba Kumiko), Sweet (Miyako Masayo), Melody (Tanaka Eriko), Kung Fu (Jinbo Miki), Prof (Matsubara Ai) and Mac (Satô Mieko) – will be going to a training camp, and staying at an inn run by the sister of their favourite teacher, Mr Tôgô (Ozaki Kiyohiko); while Gorgeous (Ikegami Kimiko) will be spending her holiday with her father at his villa in the country. Gorgeous is thrilled when her father (Sasazawa Saho) returns early from Italy, where he has been working on the music for a film, but recoils in shock and dismay when he not only introduces her to Ema Ryôko (Wanibuchi Haruko), a jewellery designer, but announces their plans to marry. Gorgeous retreats to her bedroom, where she communes with photographs of her dead mother. One photograph, taken on her parents’ wedding-day, causes Gorgeous to begin thinking about her aunt, her mother’s sister, who she has not seen for many years… At school, Mr Tôgô tells the girls that his sister is expecting a baby, and consequently will be closing her inn for the summer; therefore, they will have to make other plans. Gorgeous, who has already told her father she will not go to the villa if Ryôko is to be there too, suggests that they all visit her aunt in the country: she writes to beg an invitation. Even as she is writing her letter, Gorgeous is startled by a white cat, which suddenly jumps through the window of her room; delighted, she adopts the animal and names it “Blanche”. Gorgeous receives a reply from her aunt welcoming her and her friends, and adding that she had been hoping for such a letter for many years. Gorgeous’ father and Ryôko discuss her refusal to go with them to the villa. Ryôko suggests that, at the end of the girls’ visit to the country, she could pick Gorgeous up and bring her to the villa, so that the two of them will have time to get to know one another. Beginning their journey, the girls meet at the railway station—becoming worried when both Gorgeous and Mr Tôgô, who they have invited to accompany them, are late. Mr Tôgô, indeed, meets with an embarrassing personal mishap, and when the girls phone to check on him, tells them that he will have to join them later. Gorgeous, meanwhile, is searching for Blanche—only to find her already on the train. During their journey, Gorgeous tells her friends of her aunt’s sad history: how her fiancé died in the war, and how ever since, she has lived all alone… From the train, the girls take a bus, which still leaves them with a long walk through the countryside. When they finally arrive, the girls are delighted with the huge, rambling house, but dismayed to find that Auntie (Minamida Yōko) is in a wheelchair; Gorgeous adds that she feels guilty for not having visited her aunt before. However, Auntie reassures her—insisting that she is delighted to have all seven off them there… The girls begin to make themselves at home: Auntie directs Melody to her piano, while the others offer to clean the house and do all the cooking. The girls make themselves a meal, worrying that Auntie has slept through it and has had nothing to eat. Mac slips outside to retrieve a watermelon which, earlier, she lowered into a well to cool—and does not come back. Some time later, the girls begin to worry about her. Fantasy goes outside to search, but can find no sign of Mac. Noticing that, wherever she is, Mac did not raise the watermelon from the well, Fantasy pulls it up herself—and finds herself holding Mac’s severed head. It laughs at her…

Comments: There is a moment during the opening credits of Hausu when the viewer is informed that what they are watching is “A Movie”. At the time this seems merely an odd and unnecessary detail, but make no mistake: before another ten minutes have passed, you’ll be grateful for the reassurance.

In fact, this 1977 horror-comedy-musical-drama-tragedy-fantasy-slasher-movie-chick-flick is one of that small subset of films so determinedly – so aggressively – weird and idiosyncratic that you have to put aside all preconceptions about how movies are “supposed” to work in order to get anywhere with them. It is significant, I think, that the film which kept coming to mind as I was watching Hausu – and the fact that the two overtly have nothing whatsoever in common only underscores my point – was Eraserhead. I can think of very few other films that function so thoroughly as a reflection of their director’s psyche; nor many that, while remaining quite self-consciously a motion picture, are so wilful in their refusal to comply with any of the established rules of that form of artistic expression.

Throw into the mix hints of, say, Yellow Submarine, The Umbrellas Of Cherbourg and Suspiria; add a large serving of the absurdist visual humour we now associate with Monty Python (but which in cinematic terms probably originated with Hellzapoppin’, the 1941 film adaptation of the stage musical by Olsen and Johnson), plus the so-sincere-it-hurts sensibility and hyper-real visuals of a Douglas Sirk melodrama; and you have a film for which the word “unique” is an entirely inadequate descriptor.

Hausu was the first full-length film of Ōbayashi Nobuhiko, who in the late 1950s broke away from the medical tradition of his family to follow his passion for art and film. Already a talented painter, illustrator and musician, Ōbayashi was accepted into the liberal arts program at Seijo University, where he began to concentrate on experimental film-making. After graduating in the 1960s, Ōbayashi became a member of the Japan Filmmaker’s Cooperative. He continued to develop his style via a number of surrealist short films, which came to the attention of an executive from a major Japanese advertising firm. Ōbayashi received the traditional offer-he-couldn’t-refuse: the chance to work with cutting-edge technology and facilities, and to continue experimenting with his art, provided that the “short films” he produced and directed did as required and sold the commercial products they were built around.

The results of this trade-off astonished everyone: Ōbayashi eventually became a household name in Japan, thanks to his ad campaigns featuring American and European actors and musicians (most famously, or at least notoriously, that featuring Charles Bronson demonstrating just how manly you could be while using “Mandom” toiletries).

The studio at which Ōbayashi had been offered facilities in his ad deal was none other than Toho. By the middle of the decade, the studio was ready to try something different. In particular, with one eye on the increasing struggles of the venerable Godzilla franchise and the other on the massive success of Jaws, studio executives wanted a new kind of monster movie.

With this framework in mind, but nothing more definite, Toho offered Ōbayashi Nobuhiko the chance to make his feature-film debut—but not as a director: since Ōbayashi wasn’t technically a Toho employee, studio policy prevented him from helming the film himself.

Nevertheless, Ōbayashi set to work putting together a project for someone else to direct. Knowing that he wanted a horror movie, a monster movie, but wishing at the same time to avoid the obvious, his first step was to consult with his young daughter about what frightened her, in life and in her dreams; and so vital did Ōbayashi consider her contribution to the shaping and success of the project, Hausu carries a credit stating that the screenplay by Katsuro Chiho was “based upon an original story by Ōbayashi Chigumi”.

The result of this collaboration was too much for the resident Toho directors, all of whom declined to take on the project—with the result that Hausu remained stalled in pre-production for nearly two years.

During this time, the score for the movie was written – a blending of emphatically romantic, jazz-infused piano-pieces by Kobayashi Asei and lighter pop interludes by the band Godiego – with a soundtrack album released well before filming started; while the script was used as the basis of a manga before being novelised. Meanwhile, pre-release advertising continued to be disseminated, even as the production got no nearer starting, let alone being completed.

Eventually, the Toho executives accepted the inevitable, tweaked their policy, and hired Ōbayashi to direct. The production difficulties did not end there, however. Ōbayashi selected his young female cast chiefly from the amateurs and semi-amateurs who had appeared in some of his commercials, and it took both patience and trial and error before he could get from them the attitude he wanted. Perversely, Ōbayashi felt the girls were being too “professional”, too much like actors: he wanted them to loosen up and behave like the teenagers they were when the cameras weren’t rolling. At length he discovered that the best way to get what he wanted from his young actresses was to precede their filming sessions with music and dancing—encouraging them to play rather than work. In this way, Ōbayashi also discovered that the girls responded better to the mood set by musical cues than to his verbal instructions, and adopted this approach to direction.

Meanwhile, Ōbayashi was also involved in the creation of the film’s special effects, in collaboration with his cinematographer, Yoshitaka Sakamoto. Here, too, Ōbayashi wanted the feel of a child’s nightmare: the resulting blend of animation, split-screens, stop-motion, superimposition, fractured images, bluescreen work and practical effects is both charming and disturbing, profoundly illogical yet somehow exactly right. The director even goes out of his way to draw attention to the artificiality of the world within his film (not that it was really necessary!), via such touches as showing the edges of a backdrop.

The hallucinatory WTF-ery of Hausu is either, according to the mindset of the individual viewer, its chief delight or its final straw. However, it would be a mistake to conclude that hallucinatory WTF-ery is all that Hausu has to offer. Behind the admittedly distracting candy-coloured surface is a film that has some very serious points to make about the society that produced it.

Hausu throws the viewer from its very first moments, offering up at the outset a monochromatic, candle-lit, highly romanticised shot of the film’s central character—before pulling back to reveal that this is a staged shot, a pose for a photograph, created in a most unlikely place, a school science lab.

The names of the film’s characters are, however, probably the first thing which must be dealt with and internalised. The seven girls with whom we shall venture into the country do not seem to have names, as such, but instead carry unsubtle signifiers of a single character trait or behaviour (and are never called anything else, so we cannot tell if these are names or nicknames). Five of these are straightforward enough: Melody, who loves music; Kung Fu, the athletic one; Prof, the glasses-wearing rationalist; Sweet, the gentle, perpetually nervous one; and Fantasy, who daydreams a lot, romanticises everything, and is always being accused of “imagining things”.

In each of these cases, clearly, a Japanese term has been rendered into a near-enough English equivalent; but for the remaining two girls it isn’t so simple. For “Mac”, the constantly eating, “fat one” of the group (inasmuch as she is not quite as willowy as the rest), apparently her nickname has been derived from the Japanese word for “stomach”.

Meanwhile, what name our central character goes by depends upon what print of Hausu you happen to be watching. Evidently in the Japanese-language version, her name is “Oshare”, meaning “Fashionable”; there is one English-language version which calls her “Angel”, which seems to me to imply the wrong things about her; while the subtitles on the Criterion print call her “Gorgeous”, which is at least closer in intent to the original character name.

(Fittingly, the film has a tendency to separate both Gorgeous and Mac from their friends, although in very different ways and for very different purposes, as we shall see.)

It is Gorgeous who is posing for the opening photograph, and it is Fantasy who takes it. Our camera then pulls back to reveal that the two girls are at school, looking forward to the end of term and their summer holidays. The two girls are members of a group of seven close friends, six of whom will be going off to camp under the companionship / chaperonage of their teacher, Mr Tôgô (played by Ozaki Kiyohiko, “the Japanese Tom Jones”). Gorgeous alone has other plans: she is looking forward to spending her summer alone with her father at his villa in Karuizawa, after his absence from home for an extended period.

There is, as I say, a lot going on in Hausu, and two of its many possible readings present themselves to us from the outset. In some respects, Hausu is a coming-of-age film; when we meet its young protagonists, we find them balanced on the precarious knife-edge between childhood and adulthood. More specifically, however, this is a film about the generation gap, both superficially and in the most serious of ways. Made in the mid-seventies, when young Japanese women were breaking away from traditional female roles, Hausu reflects the resulting social conflict in a variety of ways. The girls here are, so to speak, part of a transitional generation: while love and marriage still dominate their thinking of their futures, it is clear that they are approaching this from a new and more independent perspective; making their own choices.

This point is made when Gorgeous and Fantasy briefly interact with one of their teachers, a young woman not so many years older than themselves but, in society’s terms, an adult. As they discuss their plans for the summer, the teacher admits shyly that she will be getting married. “I bet you’re marrying for love!” says Gorgeous, to which Fantasy responds, “Naturally!”—causing an awkward moment when the teacher must admit that, in fact, it’s an arranged marriage. The self-absorbed girls shrug this off, but as they literally skip away, hand-in-hand, their teacher is left looking after them rather ruefully: thinking more, or at least more positively, of the school holidays in her recent past than the marriage in her imminent future.

Meanwhile, our second theme emerges on a more personal level. In some respects, most significantly with respect to the artificiality of its mise-en-scène, in which it positively wallows, Hausu is a film about film-making and film-tropes (rather ironically, given its own refusal to toe the line); and this shows itself most clearly in the character of Gorgeous who, if she does not indulge in the standard romantic fantasies of her best friend, Fantasy, does envisage her own life in what are clearly movie terms—seeing herself as the heroine of her own and her friends’ “story”, with them reduced to supporting roles in her personal narrative. The film’s visuals support this reading, with Gorgeous alone repeatedly shot in isolation; often, indeed, made the subject of a telescoping image; which serves both to remove her from the group and to emphasise her importance, or at least self-importance.

As she fusses in the foreground with her makeup and general appearance, and as her admiring friends fawn and coo over her, Ōbayashi places Gorgeous in a series of settings that bear no resemblance to reality, but are – almost absurdly obviously – movie sets.

The origin of this deeply personal fantasy is not far to seek: Gorgeous’ father is a film composer, most recently employed in Italy. “Leone said my music was better than Morricone’s,” he reports complacently, in one of Hausu’s few overt jokes.

(Father is played by Sasazawa Saho, who later became better known as the author of a series of novels featuring the samurai, Kogarashi Monjiro.)

The relationship between Gorgeous and her father has more than a few disturbing overtones. On one hand, Gorgeous clearly views herself as having taken the place in her father’s life of her own dead mother; on the other, there is an aspect of infantilisation, seen when her father scoops her up into his arms as part of their reunion greeting.

And it is a relationship about to be challenged at all points, as Gorgeous is confronted with the beautiful young woman who is to become her step-mother…

This interlude is bizarre, funny and unnerving all at once. (And not least because the woman is introduced as “Ema Ryôko”, which was the name of a contemporary Japanese actress; although this “Ema Ryôko” is played by Wanibuchi Haruko.) As Ryôko glides forward, she brings with her a movie fantasy that outdoes Gorgeous’ own, being accompanied by a wind-machine that causes her draperies and in particular her scarf to flutter around her in a manner that unavoidably brings to mind – and particularly in conjunction with the immovable artificial sunset that hangs above the terrace of the apartment – Cyd Charisse in the “Broadway Melody” ballet from Singin’ In The Rain.

As Gorgeous stands stunned, her father goes on to describe his intended as a “jewellery designer”, but who is nevertheless, “Surprisingly good at cooking and other things too.” (!)

A distraught Gorgeous retreats to her bedroom where – after changing from her school uniform into a sundress with a Wonder Woman-like twirl – she talks to a picture of her dead mother; an interlude which grows ever darker, as she promises to “bully” her father, while scratching his face out of the family photographs. Meanwhile, though sunshine continues to pour in through the windows, this scene is accompanied by the sound of a breaking thunderstorm more in keeping with her mood… Gorgeous’ sorting through of her photo-collection gives us glimpses of ever-earlier points in the family history – with the images shifting from colour to black-and-white – and finally shows us her mother in her traditional wedding-robes, with her sister standing beside her.

It is this last photograph that brings Gorgeous’ aunt to her mind.

(Ikegami Kimiko plays both Gorgeous and her mother, something which becomes of increasing thematic importance as the film goes on.)

We are then introduced to the other five members of the group of friends, as they contemplate the summer and tease Fantasy over her crush on their teacher, Mr Tôgô. “He’s so handsome and manly!” Fantasy sighs, as her friends giggle.

By the way—if you’re going to watch Hausu, it is best to bring along a high tolerance for inane giggling, because these girls giggle about everything: everything, that is, from b-o-y-s to the atomic bomb.

No, really.

Mr Tôgô himself then shows up—an unlikely object for a schoolgirl crush, we might be inclined to think, with his dune-buggy and his cap and the lab-coat he apparently treats as casual wear. He has bad news for the girls: his sister is expecting a baby and is closing her inn for the duration, so they will have to make other holiday plans.

While this has been going on, a depressed Gorgeous has been standing a little apart, brooding on her situation. Now she breaks into her friends’ lamentations, inviting them all to join her for the summer at her aunt’s house in the country. Then, rather belatedly, she sits down to write a letter, begging her aunt to endorse the invitation, despite the fact (as we learn) they have only met twice in Gorgeous’ life, and she has only once before been to her aunt’s house.

In the middle of composing her letter, Gorgeous is startled when a white cat suddenly leaps through her bedroom window, landing on her writing-desk. As well she might be: from what we know, the apartment is on the top floors of a high-rise. Gorgeous is delighted, however, and immediately adopts the feline intruder, dubbing it “Blanche”. (In this print; in some it is called “Snowflake”.) Those of us who have been paying attention might note that the cat bears a distinct resemblance to the one that Gorgeous’ aunt is cradling in the wedding-photo.

Auntie’s reply to her letter is everything that Gorgeous hoped: she not only invites her friends as desired, but tells Gorgeous she has been hoping for just such a visit for many years.

Gorgeous’ father is not happy about her refusal to accompany Ryôko and himself to the villa, but Ryôko suggests a compromise: at the end of Gorgeous’ visit to Auntie, she will go and collect her and bring her to the villa, so that they have a chance to get better acquainted during the journey back.

The soundtrack of Hausu now does what it has been threatening to do from the outset, and breaks out into a peppy pop-song-cum-musical number, with various happy people grooving along—including a cameoing Ōbayashi Chigumi.

It turns out that the girls have invited Mr Tôgô to accompany them to Auntie’s, but this unauthorised part of the plan gets no further than the steps leading down from Mr Tôgô’s apartment building: a white cat suddenly darts across his path, causing him to stumble downstairs, and then skid all over the road, narrowly avoiding oncoming traffic, with his backside stuck in a bucket.

No, really.

At the railway-station, the other girls are becoming worried about the non-appearances of Gorgeous and Mr Tôgô. A phone-call to the latter establishes that he has had a slight accident – “Nothing serious” – but will have to join them later, after a trip to hospital. When told that there is no later bus, he responds that he will drive into the country instead.

Gorgeous, meanwhile, has been hunting for Blanche—who turns out to be on the train already. “Any old cat can open a door,” observes Prof, “but it takes a witch cat to close one!”

As the train pulls out, the scene dissolves into the picture-book being read by a young boy; a cartoon rainbow shows itself outside the window, arching over a cartoon countryside; while Gorgeous tells her friends her aunt’s sad story: a tale which unfolds in the form of a sepia-toned home-movie.

We learn then that Auntie was once engaged to a young man, a doctor like her own father, and destined to take over his hospital; but before they could be married, he was drafted. The young man swore to come back, and Auntie swore to wait for him—forever. The young man’s plane was shot down, however, and now Auntie lives all alone in the big house in the country. She never married, but her sister did: an event which coincided with the dropping of the first atomic bomb: an event reported by Gorgeous, more concerned with her parents’ wedding, as, “Peace returned.”

“It looks like cotton-candy!” giggle the girls, as the bomb explodes…

As mentioned, Hausu is a generation-gap film, and here the more serious face of that emerges in its awareness of the distance between the modern generation which knows of the war, and the one before which experienced it, whether or not they were involved as individuals.

This is the generation to which Ōbayashi Nobuhiko belongs: he was born in 1938, and lived the first years of his life in Onomichi, a town in the Hiroshima Prefecture. When his father, a doctor, was drafted, Ōbayashi was sent away from Hiroshima to the home of his maternal grandparents. His childhood friends were not so lucky.

In fact, like Gojira, but far more obliquely, Hausu is a film that addresses the bombing of Hiroshima without ever engaging with it directly. To the girls, the war is just “a story”, something that happened “a long time ago”; as indeed is Auntie’s personal tragedy, which has no more substance for them than something they might have seen sometime in a movie, and which evokes no deeper response than the inevitable sighed, “How romantic!” But the girls’ obliviousness is counterpointed by constant in-film allusions to a world over which the shadows of Hiroshima and Nagasaki still hang, and to the generation that grew up in those shadows.

By the time Gorgeous finishes Auntie’s story, the girls are on a bus heading into the depths of the countryside. They climb out at their stop in the middle of nowhere (at which point we notice that the bus is emblazoned with the emblem of a white cat), and end up standing in front of a billboard bearing an image of the countryside little less artificial than the girls’ surroundings, and which bears the stark instruction: RETURN TO THE COUNTRYSIDE GET MARRIED.

(At the time merely an odd detail – albeit perhaps a reference to a real government campaign? – in retrospect this slogan takes on the ominous overtones of HELP ELEANOR COME HOME ELEANOR in The Haunting Of Hill House.)

It turns out that Gorgeous has forgotten the way from the bus-stop to Auntie’s house, but that’s okay—Blanche knows it. The girls embark upon the long trek still before them, walking across a long suspension-bridge and through the woods, which frighten the perpetually-nervous Sweet. She complains that their surroundings are “spooky”, prompting a short lecture from the pragmatic Prof about how there are no such things as ghosts. Kung Fu further promises Sweet that if any ghosts do appear, she will take care of them.

(Ōbayashi uses this interlude to give us a captioned close-up of each girl—presumably so we have them sorted before they enter Auntie’s house.)

The girls’ first stop is at the stand of a distinctly odd watermelon-farmer (played by the film’s composer, Kobayashi Asei, who also speaks the one-word voiceover that accompanies the film’s credits: “HOUSE!”), who fortunately is able to point them in the direction of the only house in the vicinity, which sits in clear sight atop a ridge. When they have moved off – Mac separating herself reluctantly from the melons – the farmer chuckles unnervingly about how very pleased Auntie will be to have visitors…

The girls are impressed by what has rightly been described as “the mansion”, but can’t get the gates open—until they swing open for Blanche. The cat is next seen sitting in Auntie’s lap, as she in turn sits in a wheelchair. The girls gasp in dismay, but Auntie only smiles and invites them in…

Before they do, Fantasy insists upon taking a group photograph; she steps out with her camera, as the others crowd around Auntie. At the last moment, however, Blanche’s eyes flash green—and the camera leaps from Fantasy’s hands to smash itself on the ground.

Blanche’s flashing eyes are rendered in an animation effect amusing in its obviousness, but there is nothing amusing in its implications, since Ōbayashi draws a distinct visual parallel between it and the flash-photography in the wedding-scene of the “movie”, which itself acts as a form of shorthand for the exploding of the atomic bomb.

Suddenly, Mac dashes back into the scene, having taken advantage of this interlude to run back down the road and buy a watermelon—as a gift for Auntie, she insists, though her friends scoff at this obvious excuse.

Inside, the girls ooh and ahh over the house’s impressive if cobweb-festooned rooms; but almost at once, another strange interlude occurs, with the glass chandelier dropping dangerous shards. One of them impales a lizard (also an animation effect, or you’d be hearing from me on the subject), upon which Blanche immediately begins snacking; the rest threaten the girls, at least until Kung Fu leaps into action, warding them off with smartly delivered blows.

And here we find ourselves confronted with what might be, its ever-increasing eruptions of weirdness notwithstanding, Hausu’s most bewildering aspect: the capacity of the girls to just shrug off incidents which range from the merely strange to the frankly supernatural. It happens constantly, in ever-more mind-boggling circumstances, and is one of the many things about this film that you just have to roll with…

“You like piano?” Auntie says to Melody, and points her in the direction of her cobwebby but perfectly tuned instrument. That’s not all that’s in the room, and a shrieking Sweet recoils from the fakest skeleton you ever did see. That room, explains Auntie calmly, was where she used to teach piano; and before that, it was where her father saw his patients.

Meanwhile, the girls notice that the house – and Auntie’s downstairs bedroom in particular – is full of pictures of a white cat.

The girls were barely in the front door before they were offering to clean the house, and now they take over the cooking. Mac moves to place her watermelon in the refrigerator, but Auntie intervenes, explaining that it isn’t working, and pointing out the well in the courtyard instead. Gorgeous takes Mac outside and shows her how to lower her melon into the chill waters.

As they sit to eat beneath the watchful eyes of a painting of a white cat (though personally the detail I like here is the bat-shaped window), the girls worry that Auntie is missing her meal: evidently, she is sleeping through it. Mac is the first to finish up, unusually—but only so that she can go and fetch the melon. It is some considerable time, and much mutual primping, later – including Prof being reassured that she is, “Pretty without glasses” – before the others realise Mac hasn’t come back…

Fantasy goes to look for her. There is no sign of her friend, nor has the watermelon been hauled up. Fantasy sets about this last task, but is distracted by the beautiful sunset; so that she does not immediately realise what she has pulled up from the well…

“Fantasy!” croons Mac’s smiling severed head.

Fantasy drops the horrid object and stumbles away, tripping over a water barrel—which allows Mac’s head to swoop across and bite her on the butt.

No, really.

Fantasy, um, butts the head away and runs screaming for the house. “Tasty!” chuckles Mac’s head as it sails back towards the well; vomiting out what may or may not be watermelon juice before plunging back in.

It takes a while before the others can get anything coherent out of Fantasy – although to be fair to her, they seem to have unwonted difficulty joining the dots of “decapitated”, “human” and “head”. It is Auntie who offers to go outside and take a look—and the girls forget about severed heads in their astonishment over Auntie being able to walk. “You gave me energy,” she smiles at them.

As Gorgeous comforts Fantasy, the others do go outside, but all they find in the well is a watermelon. This is enough to make them put aside their concerns about Mac (they later rationalise that she went to the potato field down the road; or, failing that, is playing hide-and-seek), as they all tuck into slices of melon; all but Fantasy, who isn’t over her fright—and who gets another dose when Auntie briefly reveals that her portion of melon contains a delicious eyeball…

From hereon in, the escalating weirdness of Hausu is such that any attempt to describe what is going on unavoidably devolves into a series of helpless, “This happens…and then that happens” reports. What we take away from all this is not just that the house itself is occupying the position of the psycho-killer in a slasher movie, but that the girls are being picked off one-by-one according to their own personalities.

Consequently, we sit there slack-jawed while:

- Kung Fu is attacked by flying pieces of firewood, which she manages to fight off.

- Gorgeous, while taking a bath, seems in imminent danger of attack by her own hair. (Good grief! – was this the first instance of the Japanese obsession with scary hair? Does anyone know an earlier one?)

- Melody is bitten on the finger while playing the piano…by the piano.

- Sweet is first hypnotised by a doll which speaks her name, then attacked by rampaging pile of futons. Her friends later find her clothing – right down to her underwear – but there is no sign of her.

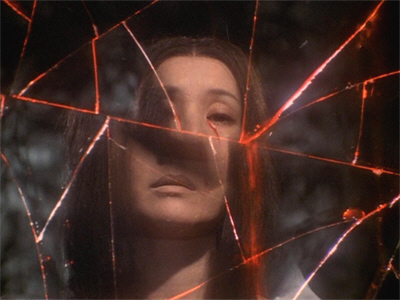

- Gorgeous is drawn upstairs to her aunt’s bedroom, where she observes terrifying things in a mirror, before being taken over by a malevolent force.

- Auntie, not content with merely rising from her wheelchair, proceeds to dance with her father’s medical-specimen skeleton, use her refrigerator as a transporter, and snack on random body-parts, presumably Mac’s.

- Blanche, in between overseeing the various attacks upon the girls, plays the piano herself, while singing along with the film’s main piece of theme-music as it toggles between diagetic and non-diagetic.

You still with me??

By this time, the remaining girls have noticed that something odd is going on. (No, really.) They search for Sweet, but find only her clothes. It then occurs to them that they haven’t seen Gorgeous for some time either. Prof and Kung Fu go to look for her, finally locating her in the bedroom which her aunt used before being confined – or “confined” – to a wheelchair; but she doesn’t seem quite herself…

She is quick to intervene, however, when Kung Fu suggests telephoning the village police about their disappearances. And although we hear the sounds of screaming and cries for help as soon as Gorgeous picks up the earpiece, she simply observes that the phone is out of order…

Gorgeous then announces her intention of going to the police station. The others object to being left at the house, but Gorgeous doesn’t listen. As soon as she steps outside, the door slams behind her—and will not open again. And as the girls dash around, looking for another exit, the house closes all its other doors and windows, sealing itself. Kung Fu tries gamely to fight her way out, but for once is defeated.

Despite all this, the rationalist Prof is (of course) still convinced that there must be a logical explanation: since Auntie, at least some of the time, in a wheelchair, perhaps the doors and windows have been wired to close themselves automatically. The others are persuaded by this, and they go looking for Auntie—but can’t find her. Frightened, the girls beg Melody to play for them, to soothe their nerves. As she does, a soft voice is heard singing along with the music. It’s Gorgeous—who must somehow have re-entered the house.

At this, the four decide to – sigh – split up: Prof and Kung Fu go looking for Gorgeous, while Fantasy stays with Melody—

—and is therefore the sole witness to what might be the greatest scene in the history of motion pictures.

Let’s do a quick survey:

Hands up those of you who know Hausu chiefly as, “The film where a girl gets eaten by a piano.”

Thought so.

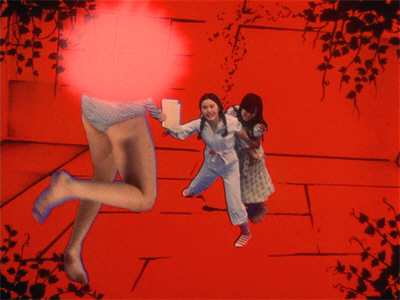

This is indeed Melody’s fate: the piano that earlier bit her finger now has a taste for her blood; and after biting off her fingers, and then her hand, it reaches out with its key-cover, grabs the rest of her, and chomps her into pieces.

Melody is surprisingly unfazed by all this; her head even floats by to raise its eyebrows at her flailing legs, which in their struggles are offering the camera a flash of her panties. “Oh, my! – that’s naughty!” she giggles.

All this while Auntie’s dad’s skeleton dances in the background, and Fantasy is forced to duck a barrage of severed limbs. (A flying arm takes out a goldfish-bowl in what is easily the film’s most genuinely horrifying moment.)

Meanwhile, the others have found Gorgeous; only she’s wearing her mother’s wedding-dress; and she doesn’t seem to have a reflection.

They find Sweet, too—trapped within the workings of the gigantic grandfather clock whose ticking echoes all around the house. As she gazes at them sadly, the gears of the clock begin to turn, splattering the inside of the glass with blood… And finally, they find what’s left of Melody, her severed fingers continuing to play the piano…

When the silent, white-clad figure that was Gorgeous yet somehow not Gorgeous vanished, she left behind a diary entitled “Lonely Days”, on which Prof immediate pounced—finding within it an explanation of sorts for their experiences, although not one in accord with her pragmatic view of the world.

It does, however, allow her to shape a plan of retaliatory action against the house—although it is the brave and athletic Kung Fu who must go into battle against—

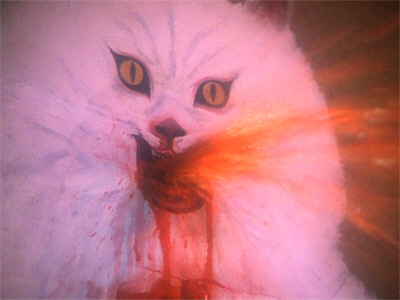

BLANCHE THE DEMON HELL-CAT!!!!

Japan has an ancient tradition of spooky cats, of course—in particular, the kaibyo, the ghost-cat, which is often presented in film as the reincarnation, or at least representation, of a woman who has met a grim fate, and more often than not wreaks vengeance on her behalf. More specifically, and ominously, there is the bakeneko, which has the ability to shift between human and feline forms.

While Blanche does not seem to fill either of these roles (though clearly not “real”, she can leave the house, which Auntie cannot), the very fact that cats hold such a prominent place in Japanese myth allows Ōbayashi to do what so many British and American horror films cannot or will not, namely, make the cat a character in its own right, not merely a symbol.

Blanche is, indeed, an amusingly pervasive presence, manifesting in a variety of forms—from a seemingly innocent pet, to a set of statuettes upon the mantelpiece, to countless photographs, to a distinctly Dorian Gray-like picture on the wall. And if you thought what ultimately happened to that painting was bizarre, well, you ain’t seen nothing yet.

I suppose I could at least try to describe what happens next…but really, this is one of those times when you’re grateful for the old saw about a picture being worth a thousand words…

Alas— Despite what for a few moments looks like an improbable victory, in the end the forces of evil are too much for Kung Fu and Prof: the former is taken out in a vicious attack by a light-fitting – which does not immediately stop her severed legs from fighting on, and quite successfully, on their own – while Prof is dragged down into a rising tide of blood by a saw-toothed piece of pottery as she gropes around for her lost glasses. She does not go, however, without uttering this film’s signature line of dialogue:

Prof: “It’s unscientific, unexplainable, unnatural, unreasonable. It doesn’t make sense!”

Except— I think it does, at least on the emotional level.

I’ve suggested a couple of different readings already for Hausu, but another, more pointed one emerges over the course of the film. This is, as I have suggested a coming-of-age film of sorts (except, alas, none of our characters will ever get to “come of age”); it is also a rumination upon the place of young women in a changing society: the tension between the new possibilities for independence and the older, far narrower traditions; with the most potent weapon in the armoury of the latter being the way that girls are indoctrinated from their earliest years with unrealistic romantic ideals.

Though they no doubt consider themselves thoroughly modern young women, the girls spend an inordinate amount of time contemplating love-and-marriage; in fact, to a degree which Ōbayashi deliberately makes absurd and unnatural. Every man they encounter, in any context at all, is sighed over as “manly and handsome”—even Auntie’s fiancé, as they watch (otherwise unmoved) his bloody death during the war; even the profoundly ordinary Mr Tôgô. In the wake of Sweet’s disappearance, Prof comforts the sobbing Fantasy with the assurance that, “Your love, Mr Tôgô, will soon be here.”

Prof: “He’s a man, after all. He can help us!”

On cue, Fantasy goes off into a daydream about herself as the damsel in distress, and Mr Tôgô as her knight in shining armour, riding in on a white charger to save her…

…a ludicrous vision made only more so by the film’s periodic cutaways to this “romantic hero” as he gets stuck in traffic, stops to eat noodles, and debates fruit with the watermelon salesman; all in the wake, of course, of having a bucket surgically removed from his buttocks. As a warning about the perils of waiting for a man to come along and “rescue” you, this sequence makes its point with brutal jocularity.

But even more bitter, yet oddly heart-rending, is the exchange between Prof and Fantasy, in the wake of Auntie’s declaration in her diary that she knows her fiancé will return one day, because he promised.

As the floor separates into matting, leaving the girls floating on a rising tide of blood, Fantasy lets out a despairing cry:

Fantasy: “Mr Tôgô!”

Prof: “Maybe he isn’t coming.”

Fantasy: “Why not? He promised!”

In fact, Hausu finally positions itself as a cautionary tale about the destructive potential of romantic love. The earlier revelation that Auntie is dead – has been dead for many years – comes as no surprise to the viewer; nor, from a certain perspective, does her determination to keep her own promise of waiting “forever” for her fiancé, “With Blanche in my arms.” Thus, her death notwithstanding, Auntie has continued to inhabit the house as a sort of Miss Haversham figure in reverse: one who, instead of wearing her wedding-gown in perpetuity, must go to terrifying lengths for a chance, denied to her in life, to don the traditional white robe; who, instead of punishing men, sees all young women – who might yet have the opportunities of which she was robbed – as her enemies; her rivals, who must be destroyed.

The house itself, meanwhile, has become an extension of Auntie’s increasingly malevolent personality, the weapon by which she takes her revenge—and worse. Though we see Auntie chiefly as a ghost, the film also presents her at various times as a ghoul and a vampire. As per ancient tradition, she explicitly devours virgins—devouring not only the flesh, but the hopes and optimism and romantic longings of the girls drawn into her trap. The entire second half of this film consists of scenes in which the new generation is mercilessly destroyed by the preceding one, that which had its hopes left in ruins by the war.

In all this, too, we find the significance of the unsubtle characterisations of the girls—why they are picked off as they are, and in the order they are—and the reason why Mac and Gorgeous are both tacitly separated from the group.

Mac, the outlier, the only one who doesn’t reflect a recognisably feminine persona, is removed fast and early, turned into a version of the food she has been consuming non-stop; it is by consuming her that auntie begins to regain her strength. Sweet and Melody, conversely, are taken down by their overtly feminine preoccupations—the former with the housework, the latter with her music. (Auntie, we are reminded periodically, used to give piano lessons: presumably a suitable occupation for an unmarried woman.) Meanwhile, it is the relatively “unfeminine” Prof and Kung Fu who put up the staunchest resistance to the house; though in both cases the viewer has been “reassured” about them, with Prof encouraging Fantasy in her daydreams, offering to do the cooking, and beaming at being told she is pretty without her glasses, and Kung Fu’s athleticism excused by the fact that the ultra-feminine Gorgeous, too, excels at sport.

(This unfolding theme throws new light upon the peculiar early remark about Ryôko, that she is, “Surprisingly good at cooking.” Evidently as a career woman, she would be expected to lack such basic female skills.)

Gorgeous herself is uniquely vulnerable to the house’s influence, in herself and as a blood-relation—and the daughter of the woman who alone got to wear the family wedding-robes. And it is, of course, her father’s introduction of Ryôko into their lives that prompts Gorgeous to invite herself and her friends to Auntie’s house. In reacting to her father’s plans to remarry as an act of romantic betrayal – of her mother, of her – Gorgeous reveals just how emotionally akin she is to Auntie. Whereas the other girls must be overcome and brutally dismembered, Gorgeous herself is subsumed into Auntie’s personality with frightening ease.

Yet it seems that the house wants Fantasy as much as it does Gorgeous. Though Kung Fu and Prof each meet a gruesome fate, Fantasy herself is pulled to—well, not to safety, exactly, but out of the rising blood-waters—by Gorgeous – or what used to be Gorgeous, a Gorgeous whose reflection is now that of Auntie – and clasped comfortingly in her arms. “Mama!” whispers Fantasy as she falls asleep, and here we understand the sound of a baby crying that has punctuated the film’s soundtrack: Fantasy’s fate is to be the child that Auntie was also denied in life.

The camera pulls away here, leaving them together, Gorgeous and Fantasy; the two girls whose inner lives were shaped and dominated by their capacity for romantic fantasy; two girls now occupying the definitively female roles of mother and daughter.

This is, indeed, the last we see of Fantasy, but not the last of Gorgeous. Like Auntie before her she is waiting for a visitor; waiting for Ryôko, who is coming as promised to pick her up.

Ryôko’s approach to the house, and her wandering of the grounds – during which she gasps and coos over its many beauties, as her scarf and draperies flutter around her – is underscored by a soppy love song which, in context, is viciously cynical; as indeed is the paean to deathless romantic love that follows—spoken by Auntie, her faith unshaken. Because, you see, he promised…

While I’m prepared to admit that (as usual) I’m probably reading far too much into Hausu, I won’t listen for a moment to those people who contend that there is nothing here to read: that the film is an empty exercise in visual trickery. There’s far too much method in Ōbayashi’s madness for that, too much careful linking of the deceptively random imagery—for example, the way in which the early broken-up framing of Gorgeous through the uneven rectangular windows of her apartment, as she learns she is to have a step-mother, foreshadows the shattering of the mirror which signals her possession by Auntie.

In fact, there is so much going on in this film, both visually and aurally, that you cannot possibly absorb it all on a first viewing; while certain details only reveal their significance after the event, such as the seemingly randomly-placed baby cries, which are not random at all…

Hausu was not well-received critically in Japan, but it was a financial success, finding its audience predominantly amongst the younger generation of which Toho was so painfully aware, and so painfully uncertain how to cater to. The film’s international reputation was slower to build, not surprisingly, but both in its own right and as an illustration of the artistry and imagination (and insanity) of Ōbayashi Nobuhiko, it has by now received at least a measure if the acclaim it deserves—including, notably, the accolade of a Criterion release. And while – to put it mildly – it is not a film for everyone, those coming to it with an open mind, or looking for something “a bit different”, are likely to be rewarded beyond their very wildest dreams…

♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦

This review is part of the B-Masters’ collective cry of, “WTF!?”

You probably already know this, but the floating head that bite the girl is a traditional Japanese monster (Nukekubi). Ghosts with unnaturally long (and unnaturally active) hair are also traditional–Japanese women typically had long hair but always wore it up in a bun, the only time it was let down was for the person’s funeral, hence a woman walking around with her hair unbound was potentially a ghost.

The folktales and ghost stories of Japan seem exceptionally weird to Westerners (the hopping one-eyed umbrella spirit, anyone?); this movie doesn’t sound particularly strange in that context. Especially compared to the excesses of later Japanese cinema!

LikeLike

I knew about the Penanggalan but I didn’t know there was a Japanese version, so thanks for that.

Yes, it’s always clear that the hair business was drawing on an old tradition too, but I wasn’t sure when that started showing up in films, which is something Dirck has answered for us—

LikeLike

Huh, I hadn’t thought of the similarity to the Penanggalan. Talk about weird–I still remember being stunned when I found out that the Penanggalan was an actual mythological creature, rather than one of Gary Gygax’s bizarre inventions. The Japanese version is a lot less disgusting, though–no entrails!

The Hellboy comic used the Nukekubi to great effect in one issue.

LikeLike

That Hellboy comic was my introduction to the Nukekubi, oddly enough! One of the many things I love about that series is its delving into world mythologies; more than one critter was brought to my attention in its pages.

LikeLike

I *thought* the hair thing showed up in something a little earlier, and a little straining brought up an answer from the pits of memory– it was the first sequence in Kwaidan (1965), and as mentioned above there’s enough of a foundation for it that it may have appeared even before that.

LikeLike

—which just goes to prove it’s been way too long since I watched Kwaidan, as I didn’t remember that (I tend to remember the tattooing) – thanks!

I certainly wouldn’t be surprised if there were earlier iterations still, so if anyone knows, please chime in!

LikeLike

I’m in agreement with Dirck; if there’s an earlier incarnation of the hair in Japanese cinema, I am unfamiliar with it. After seeing Ring and its ilk, I had thought it was a fairly modern thing. Hausu presented me with what I thought might be its precursor (I also found myself wondering if a young Sam Raimi hadn’t somehow seen it, although it seems unlikely). So you can imagine my surprise when I saw Kwaidan.

LikeLike

This ties into the conversation we’re having over at the B-Masters blog, about the (apparent) genre gap between Hausu and Ringu. Clearly all these details were aspects of Japanese legend and mythology, and turned up occasionally in Japanese horror films, but it wasn’t until Ringu that scary hair became a thing in its own right. (As opposed to ghost-cats, which were a thing from the earliest days of Japanese cinema.)

LikeLike

How about Lady Wakasa from “Ugetsu”? It’s been decades since I’ve seen the film but I think she appeared with her hair down.

LikeLike

Another for The List, thanks!

LikeLike

I saw this film a couple of years ago, and alas, it just seemed like weirdness piled on weirdness to me–though I remember being impressed by the sheer weirdness of it. If I’d read this review beforehand I probably would have appreciated it more.

Maybe I’ll put it back in the Netflix queue….

LikeLike

Well…it *is* weirdness piled on weirdness, but maybe not “just” that. If you do take a second look, I’d be interested to know what you think.

LikeLike

There’s something here that many later films could have benefited from imitating: if you’re going to write characters with one trait each, own it and make them explicitly symbolic, rather than “girl called by the name of the actress whose entire character is built round being (brainy, sporty, emo, etc.)”.

LikeLike

But only if they *are* symbolic, not just if you’re a bad / lazy writer.

LikeLike

Maaannnn….

While you brought up The Haunting of Hill House, Fantasy and Gorgeous being pressed into their roles as fantasy-fulfillment mother and daughter reminds me in some ways of We Have Always Lived In The Castle. This film is so saturated in multiple meanings and symbolism it’s like watching the offspring of Freud and Jung’s subconscious-es.

The point of the generation gap, and the seeming hopelessness of being able to tell the next generation with any emotional accuracy what something like WW II was really like, also explains the oversaturation of imagery and surrealism. The actual experience was so stark and horrifying that it sealed the entire war generation into its own house; the only way to convey any part of that experience is through pranks, allurement, and manipulation of reality into a bizarre carnival to entice the children of the post war generation long enough to grab them by the throats and hiss “You don’t know. You don’t deserve reality or peace if what we went through is just some story.”

LikeLike

And I guess the overriding point is that Ōbayashi sat between the two: he was of the war generation, but he was a child, not an adult, aware and unaware of what was going on—and so was able to see the gap from both sides as he grew older.

LikeLike

Boy I sure did enjoy this movie. The bizarre tonal shifts. The butt-biting floating head. The over-the-top violence, and the strange indifference of the characters to the violence, like the girl who gets her fingers bitten off by the piano and barely blinks. The good-looking naked women. This review did not even mention how the teacher does not come to the rescue because he gets turned into a pile of bananas.

Great flick.

LikeLike

Finally watched this again, in the nice Criterion transfer…though the untranslated word “Panavision” in the end credits makes me wonder if I’ve seen ALL of it…

I still find a lot of it deliberately disjointed–it’s like an episode of “Pee Wee’s Playhouse” directed by Sam Raimi, with a script by several people on a blind drunk who had never met, and just mailed in random pages, edited by David Lynch.

But it’s a lot more compelling and interesting given your analysis. To the point where instead of throwing up my hands and saying “What next?” I’m instead studying the screen and saying “Hmmm…interesting.”

And Blanche is, like all cats, eminently petable and endlessly…petable. Yeah, she’s evil and everything, but…cat! Cat!! No one can resist cats! Unless they’re, you know, “sane” and stuff. Boring dull people!

Again, I want to thank you for an excellent review. If there were any justice in this world, Criterion would reprint your review in the DVD booklet. If nothing else, it would reduce the amount of confusion in the world…but then, the makers of “House” would probably disapprove and want more confusion.

But, hey, the heck with them! CAT EATS EVERYTHING!

LikeLike

I really appreciate that, thank you!

And yes, I would very much like to live in a Blanche-themed house… 🙂

LikeLike

TCM had this in their odd Film Noir insomniac time slot and I couldn’t wait to see it based on this review.

I enjoyed the IMDB review that called it a movie that resembles the product of Beetlejuice directed by Dario Argento, which reminded me of my own description of Dead Alive – the movie that answers the question, “What would you get if you crossed the Three Stooges with Clive Barker?”

Best scene of a piano eating a person on film ever. EVER.

LikeLike

Appreciate that! – but wow, talk about an unlikely TCM film.

We need more to choose from… 😀

LikeLike

TCM also had Witchboard followed by Courage of Lassie recently. That was an odd morning since I watched both.

LikeLike

As I’ve said before, my own favourite accidental double-bill was a homemade video tape (which I may still have around?) which ended up giving me Judgement At Nuremberg plus Hollywood Chainsaw Hookers. 😀

LikeLike

On a sad note, it looks like the director, Nobuhiko Ôbayashi, passed away this past Friday, April 10th. I think a rewatch of this is in order now.

LikeLike