“You must prevent them from entering Oz. They have the papers, and the girl is Queen Dorothy!”

Director: Larry Semon

Starring: Larry Semon, Dorothy Dwan, Oliver Hardy, G.Howe Black (Spencer Bell), Charles Murray, Josef Swickard, Otto Lederer, Frank Alexander, Bryant Washburn, Mary Carr, Frederic Ko Vert

Screenplay: Larry Semon, Leon Lee and L. Frank Baum Jr (Frank Joslyn Baum), based upon the novel of L. Frank Baum

Synopsis: A toymaker (Larry Semon) reads a story to his granddaughter, telling her of the Land of Oz and the disappearance of its baby princess; and how, nearly eighteen years later, the angry populace gathered at the palace, where Prime Minister Kruel (Josef Swickard) sat upon the throne. The people, under the leadership of Prince Kynd (Bryant Washburn), demand the return of their rightful ruler. Acting on the advice of Ambassador Wikked (Otto Lederer), Kruel announces that he will ask the Wizard of Oz (Charles Murray) to find the queen, in reality begging the Wizard simply to create a diversion… Here the child interrupts, demanding to hear about Dorothy, the Scarecrow, and the Tin Woodsman. The toymaker turns the pages, and tells of a farm in Kansas, where Dorothy (Dorothy Dwan) lives with her Uncle Henry (Frank Alexander) and Auntie Em (Mary Carr); and where, as she approaches her eighteenth birthday, she is courted by two of the farmhands, one shy (Larry Semon) and one self-confident (Oliver Hardy). Dorothy complains to her aunt of her uncle’s harsh treatment, and Em confides that he is not Dorothy’s real uncle. Em goes on to describe the night that she and Henry found a baby in a basket on their doorstop. With the child were two letters, one commanding that the other not be opened until the baby’s eighteenth birthday, under threat of death and desolation… Meanwhile, in Oz, Kynd threatens Kruel with the dungeon unless the queen is returned. Kruel confides to Wikked that certain compromising documents are in a place called Kansas, and orders him to retrieve them. Dorothy’s birthday arrives, and she begs her uncle for the mysterious letter. Before Henry can do anything, a plane lands on his property, from which emerges Wikked and his men. Wikked demands the letter, but Henry refuses to hand it over. Later, observing the self-confident farmhand rebuffed when he offers Dorothy a ring, Wikked takes him to one side and promises that if he helps retrieve the letter, he will both earn a great deal of money and the win girl he loves; warning him, too, that if Dorothy reads the letter, she will never be his. Henry takes the letter from its hiding place, but as he is about to give it to Dorothy, Wikked and his men threaten the family with pistols. A distraction allows Henry to hide the letter again, and he refuses to tell Wikked where. Wikked and his men seize Dorothy and hoist her up on a wooden structure, warning that unless Henry hands over the letter, she will plunge to her death. At that moment, however, Wikked’s new henchman finds the letter. He is about to hand it over when the shy farmhand steals it. In the ensuing chase, he both evades his rival and saves Dorothy’s life. Suddenly, a violent storm breaks. Dorothy, Henry, the two hands and Wikked take refuge in a shed, which is ripped from its foundations and carried all the way to Oz…

Comments: It seems to me that the only sane response to a viewing of Larry Semon’s version of The Wizard Of Oz is a cry of…what the HELL was he thinking!? – if, that is, it can in fact be considered permissible to use the words “Larry Semon’s version of The Wizard Of Oz” and “sane” in the same sentence.

Even more than my discussions of the earlier Oz adaptations, this one needs to be prefaced by a history lesson, since without an understanding of who and what Larry Semon was, we will never begin to grasp how this bizarre non-rendering of L. Frank Baum’s story came to exist in the first place.

Though today he is best known chiefly as a footnote to movie history, either for this very movie, or for the fact that he worked with both Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy (although never both at once), in his time Larry Semon was one of the leading silent comedians, second only to Charles Chaplin in terms of both popularity and salary.

Semon’s career peaked in 1920 with the two-reeler The Grocery Clerk, a quintessential example of his frantic, sight gag and stunt-filled, little-guy-makes-good comedies. At this time Semon was attached to the Vitagraph Company, with whom he had signed a contract the previous year that truly rivalled Chaplin’s. Riding high on the profits of their star’s short films, Vitagraph raised his budgets and granted him artistic autonomy. It was a decision that many people would come to regret, and none of them more bitterly than Larry Semon himself.

Larry Semon was not the first film-maker ruined by being given everything he wanted, and he certainly wouldn’t be the last; but Semon’s self-destruction took an interesting form. As Semon’s films became more expensive, they also became more remote. While lower budgets had forced him to exercise his ingenuity in sight-gags that spoke directly to the audience, Semon now spent a fortune on ever more elaborate sets and stunts, while the more intimate aspects of his films were lost. In fact, 1922’s The Sawmill – for which Semon seems to have purchased a real sawmill, rather than building a mock-up – cost more than an average feature-length production.

(We should note, however, that there may have been an underlying agenda to Semon’s behaviour: in 1920, Vitagraph sued him for deliberately increasing costs, in what they asserted was an attempt to get out of his contract.)

Vitagraph might have put up with this had Semon’s films continued to be as profitable as they once had been, but it was also around this time that a complaint began to be heard with increasing frequency: that all Larry Semon’s films were the same. It was a warranted criticism. The same gags were used and re-used; the same stunts appeared over and over, in particular those featuring falls from high places; while Semon’s apparent obsession with water towers became a running joke in itself, although not in a good way.

Vitagraph heeded these complaints, which issued from critics and the public alike, and forced them upon Semon’s attention. Oddly, while it seems that Semon did listen, the lesson never took hold: after any such lecture, he would respond with some welcome new material, only to fall back onto the same old stuff in the film after that.

After years of wrangling and legal battles, Vitagraph and Larry Semon parted company in 1924. Semon negotiated himself a contract with an independent producer named Isaac Chadwick, under which he intended to meet a new film-making challenge. By this time, Semon’s most successful competitors, Charles Chaplin and Buster Keaton, had both made the step-up to feature film production; Semon intended to do the same, announcing a two-film schedule: The Girl In The Limousine, a comedy about Semon falling foul of a gang of thieves, and an adaptation of The Wizard Of Oz.

No prints of the former film survive today, so we cannot judge for ourselves; but contemporary reviews of The Girl In The Limousine were scathing and box office returns miserable.

The experience of making Wizard Of Oz aged Larry Semon just a tad…

Nevertheless, Semon and Chadwick pressed ahead. Semon claimed that he had wanted for years to film a version of L. Frank Baum’s story, and his initial behaviour seems to confirm this. He paid a large sum to the Baum estate for the rights to the novel, and hired Baum’s son to work on the screenplay with him. (He is trumpeted in the titles as “L. Frank Baum Jr”, although he was so only in the sense that Creighton Chaney was “Lon Chaney Jr”.) All evidence suggests that Semon was quite sincere in his desire to bring the author’s classic tale to the screen.

So what on earth happened?

Well, the short answer seems to be that, left to his own artistic devices, Larry Semon did what Larry Semon always did: he made a Larry Semon film. The result is a product that reminds me of nothing so much as the soft- and hardcore fairytale adaptations of the sixties and seventies; except that, in grafting pornography onto children’s tales, the makers of those films were being calculatedly transgressive; whereas Larry Semon—well, heaven knows what Larry Semon intended, but whatever it was, he seems inadvertently to have created a forerunner to some of today’s more unfortunate comic book movies, producing a film that manages to offend the serious fan and the casual viewer alike.

The distance of this film from its source can be summed up by the fact that, in a film called “Wizard Of Oz“, the wizard is merely a throwaway bit-character; although perhaps the most striking thing about this adaptation overall is the elimination from the story of all its fantasy elements: there are no witches, no talking scarecrows, no metal men, and the lions are real. At the same time, the film does play out in what we might call “the land of slapstick”, wherein people can survive falls from high places and other such physical dangers provided that their doing so can be made some sort of punchline.

Charles Band’s The Wizard Of Oz.

So in assessing Larry Semon’s Wizard Of Oz, first we have simply to accept that it bears no more than the very vaguest resemblance to Baum’s story, and that attempting to judge it from that perspective is a pretty pointless exercise. Unfortunately, assessing it as straight comedy, or even as “a Larry Semon film” doesn’t help either. I am not in a position to judge how representative of Semon’s work this film is, but on this example alone I’m not impressed: the slapstick is fairly crude, and scenes go on well after their potential for humour is exhausted. As for Semon himself, far from being an appealing personality, I actually find him a little creepy. He also overdoes the poor-pitiful-me routine which, while not an unfamiliar ploy in comedy of this kind, needs to be carefully handled if, in its bid for sympathy, it is not to overshoot the mark and do the opposite.

The other issue here is that, at its worst, the film is very much a product of its time, with wince-inducing use of stereotypes. The third farmhand who appears in this version of the story is played by the black actor Spencer Bell, whose character is called “Snowball”, and who was billed in a number of his films as “G. Howe Black”. Snowball is exactly what you’d expect in a film of this time, lazy, and thieving, and an eye-rolling, teeth-chattering, knee-knocking coward. (When the characters start disguising themselves as Oz-ites – don’t worry, we’ll get to that – naturally, Snowball ends up as the Cowardly Lion.)

However, the really bizarre thing here is that, if you look at this film squarely, you can tell that Larry Semon actually had a fair amount of respect for Spencer Bell, who gets plenty of screentime, probably more than Oliver Hardy, and whose character is allowed to save the day at the end of the film…sort of; we’ll get to that, too. I was particularly taken by the moment when Larry offers Snowball a comradely handshake, upon the latter being cast into a dungeon. It’s as if Semon was obliged to include all the demeaning stuff in order to get away with the rest (something we see later in the films of Mantan Moreland).

In any case, Larry Semon’s treatment of Spencer Bell is no worse than that doled out to most other black actors of the time (she said, damning him with faint praise); and in fact is not nearly as bad as Semon’s handling of his fat actors. It was a cherished tenet of Semon’s film-making that few things were funnier than the physical humiliation of a fat person. By way of justification, he invariably made the fat person evil; and the fatter he was, the more evil he was sure to be.

“I took them out of their protective mylar packaging? What was I thinking!?”

Wizard Of Oz gives us two evil fat guys, Frank Alexander as Dorothy’s Uncle Henry, and Oliver Hardy as Larry’s own romantic rival. While Alexander was certainly of impressive dimensions, Hardy at this time was much thinner than we are used to remembering him, barely more than slightly chubby; but compared to the skinny Semon, he looks fat; so we are not surprised when he eventually sells out to Prime Minister Kruel. And it was his evil fat guys who were made the brunt of Semon’s other obsession: gooey stuff. Whether it was molasses, or jam, or oil, or whitewash, you could be certain that at some point either it would get poured onto the fat guy, or that the fat guy would be dumped in a barrel of it.

And it doesn’t stop there. I pointed out during my review of The Last Warning that bodily humour was a feature of movie-making even as early as the 1920s, and Larry Semon was one of its leading exponents. He particularly enjoyed a bottom joke. In fact, if it kicks, or bites, or pokes, you can be very sure that it will make contact with someone’s backside over the course of a Larry Semon film.

And finally, Wizard Of Oz has the very rare distinction of being the only film that I can think of where you get to see a duck projectile vomit.

So. Onwards.

As so many do, Wizard Of Oz has a framing story, that of an elderly toymaker (Semon again) reading to his granddaughter. Thus we hear of the disappearance of the rightful ruler of Oz – here oddly referred to as a “township” – when she was only a baby; and the machinations of the usurper, Prime Minister Kruel, who conspires with Ambassador Wikked and Lady Vishuss in order to hold onto the throne.

HI-larious!

Opposing Kruel is Prince Kynd, who leads the townspeople when they invade the throne-room – all of them politely standing still and quiet until they get their cue, at which point they begin fist-shaking – and demand the return of their queen.

What Kruel is supposed to do, if she’s been missing for eighteen years, remains unclear; but he is sufficiently shaken by Kynd’s threat to throw him into the dungeon to ask for Wikked’s advice. Wikked suggests calling in the Wizard, upon which the audience is informed via title card that here this character is “just a medicine-show hokum hustler”, something Kruel evidently doesn’t know.

Kruel begs the Wizard to create a distraction, and he obliges by summoning up “The Phantom Of The Basket”, an individual in flowing robes and a peacock-tail headdress played by one “Frederic Ko Vert” – I think we can be safe in assuming, not his real name – who was not only a well-known female impersonator, but also designed the film’s costumes (not that they’re anything to write home about, other than his / her own). S/he performs an elaborate dance while the unsophisticated Oz-ites fall back in understandable alarm. Prince Kynd only laughs, however, declaring this interlude to be “a lot of applesauce”; a reaction that suggests that Kynd spends the time that he is not onscreen – which is a lot – hanging out in Parisian nightclubs.

At this juncture, the toymaker’s granddaughter, no doubt speaking for the vast majority of this film’s viewers, interrupts to declare that she doesn’t like this, and wants instead to hear about Dorothy, and the Scarecrow, and the Tin Woodsman. So her grandfather turns the page, and we hear about “a rose that bloomed in Kansas”; and if you think Judy Garland was too old to play Dorothy, well…

“I’m Kruel; she’s Vishuss. Any questions?”

Shortly after the release of Wizard Of Oz, the twenty-year-old Dorothy Dwan became Mrs Larry Semon, which explains both her casting and the plethora of loving close-ups. Our star really was called “Dorothy”, by the way, although her surname was not her own. Debate might continue over Jessica Lange’s character in King Kong, but this was a tribute to director Alan Dwan, chosen in place of the actress’s real surname…Smith.

So we meet sweet, grey-haired Auntie Em, fat and angry Uncle Henry, and the two farmhands in love with Dorothy – neither of whom is actually given a name, so I’m just going to call them “Larry” and “Ollie”.

Uncle Henry proves his “fat = evil” credentials by threatening everyone with violence, particularly Dorothy (Ollie intervenes, and gets a sock on the jaw for his trouble); but considering that on this farm we have a healthy young woman who leaves the backbreaking physical labour to her elderly aunt while she literally smells the flowers, one farmhand who spends all his time flirting, one who likes to doze in the barn, and one who likes to steal watermelons (guess which?), I find myself oddly in sympathy with the angry violent fat guy.

A great deal of allegedly comical fighting and chasing and bottom-humour follows: Larry gets kicked by a donkey, sails over a fence and lands in one of those Kansas cactus-patches we’re always hearing about; he detaches the cactus leaves from his own backside and tosses them back over the fence, where Uncle Henry is just about to sit down. Larry tries to give Dorothy a lollipop, but she’s too busy flirting with Ollie to notice. A duck eats the lollipop instead and, well, we know how that ends. Larry gets a bee swarm all over his backside, but they desert him for Uncle Henry’s vast posterior…

Having exhausted the possibilities of brains and hearts, the Wizard looked to expand his horizons…

Oh, look, I’m not going to report this stuff in any detail. Suffice it to say that if you enjoy slapstick, you’ll probably enjoy this; while if you don’t, you’ll probably be in agony.

What I will comment on is an unfortunate phenomenon, which perhaps was another problem with Larry Semon’s films overall: that whenever he does come up with something really funny – in this film, his interaction with a real lion, or evading Ollie by playing a version of the shell game with a series of wooden crates – he tends to spoil it by dragging the joke out to untenable length. Still, he’s hardly the only comedian in history who didn’t know how or when to end a sketch.

Let’s see, what’s relevant in all this? Probably only that both Ollie and Larry are in love with Dorothy, and Ollie has his nose in front. Dorothy accidentally propels whitewash all over Uncle Henry (told ya), and when he objects, Dorothy complains to Em that the way he treats her, you’d never think he was her uncle; causing Em to ’fess up that, well, he isn’t. Dorothy is so delighted by this revelation, it doesn’t occur to her that this means Em isn’t her aunt, either; that, or she doesn’t care.

Em then describes the night she and Henry found a baby on their doorstep, accompanied by two letters, one insisting that the other not be opened until the baby turns eighteen, under threat of all sorts of awful penalties.

Back in Oz, Kynd and the populace are still shaking their fists at Kruel, who decides that he’s better retrieve those letters. You know, those letters that say who the baby is? That he left? When he kidnapped her?

And better yet, he didn’t strap her breasts down.

(Later in the film, Kruel claims he removed the baby princess for her own safety. Maybe that was true? – only later he grew corrupt and didn’t want to give the throne back? That’s all I got—and it’s more than Larry Semon gives us.)

Anyway, Kruel sends Wikked to Kansas to get the letters back. He flies there in his biplane (!) with four of his men, all dressed as gauchos (!!). Wandering up to the front gate, Wikked says to Henry, “Years ago a sealed envelope was left here. I want it.” – then looks surprised when Uncle Henry declines to hand it over. Wikked then tries to buy the letter, at which Henry gets angry.

Actually, for a wicked uncle, Henry rather steps up to the plate here. Or perhaps he just realises that this letter is his ticket to getting Dorothy off his hands.

Meanwhile, Larry and Ollie are competing for Dorothy’s attention. (If I was feeling nasty, I might say that the little tease is playing them off one another.) Ollie offers her a ring, which is declined; a rebuff witnessed by Wikked, who sidles up to Ollie and whispers that if Dorothy reads the hidden letter, she will never be his…but that there might be a way he can get the girl and a bundle of money besides…

Uncle Henry finally bites the bullet and digs up the casket containing the letter, but Wikked stops Dorothy from reading it by the simple expedient of shoving a pistol in everyone’s face. Uncle Henry manages to slip away and re-hide the letter – can you imagine Uncle Henry doing anything by stealth? – and when he refuses to give it up, one of Wikked’s men suggests, “Chief, let’s tie her to the tower!”

“And at #1 in our list of The Top Ten Things You Never Thought You’d See In An Oz Movie…”

And yes, Uncle Henry’s farm just happens to have an inexplicable tall wooden thing that just happens to have a rope and pulley system attached to it. So soon Dorothy – or a fair-to-middling approximation of her – is dangling from the thingy, while Wikked lights a fire under the suspension rope, threatening to let her drop unless Henry spills.

Ollie, however, finds the letter. Larry sees him find it and steals it from him. A protracted chase follows, climaxing – naturally – in a climb up a silo, and – naturally – a swan dive off it. Larry lands in a hay wagon, Ollie on the hard, hard ground…though he is none the worse for it.

Dorothy’s rope is just about to give way (hoo, that Uncle Henry is one cold-blooded badass!), but Larry sprints across, arms outstretched, and catches her as she plunges to ground. When the dust clears, the two of them are climbing out of a crater…

This thing’s not a fantasy because it takes place in Oz, you know.

Speaking of Oz – you remember Oz, right? – something vaguely recognisable happens next: a violent storm breaks. Animated lightning chases most of the characters into a small shed, which is ripped up and carried off. The animated lightning attacks Snowball, too, but it bounces off his skull, ho, ho; so instead the lightning “hot foot”-s him, chasing him up and across the clouds, until he catches up with the shed and falls into it through a trapdoor in the roof.

We see now that Aunt Em is not amongst those carried off by the storm, so we can only assume that she is buried somewhere under the ruins of the farm, and that her crushed remains, like those of Wikked’s henchmen, will presently be discovered by the Kansas clean-up squads.

“Now, now, Em… She isn’t really our niece, remember.”

In Oz, the shed crashes onto a cliff-top, rolls off the edge and plunges to the ground, where it shatters. Everyone emerges unscathed. Naturally. After briefly puzzling over their whereabouts, Larry remembers that he has the letter, which Dorothy finally opens, learning that she is the rightful queen of Oz. And that her name is Dorothea, which no-one takes the slightest notice of.

Detaching himself from his travelling companions, Wikked sprints back to the “township” and breaks the news to Kynd, Kruel and the Wizard. Kynd takes one look at Dorothy and starts licking his chops. Kruel tries to have the new arrivals all arrested for trespass, but Kynd intervenes and reads the letter. Kruel, thwarted, turns to the Wizard and implores him to get rid of the interlopers, preferably by turning them into something: “Make monkeys of them.”

The Wizard, realising that the jig is almost up, confesses his incapacity to Larry. Larry and Ollie obligingly hide, so that the Wizard can claim that he made them invisible; but soon he is able to insist that he did transform them. How? Well, you see, Larry hides in a cornfield, near a scarecrow; and Ollie hides behind a pile of scrap metal…

Yes.

To give the devil his due, Semon makes a convincing and, more significantly, an appealing Scarecrow, during these few minutes when he remains in character, making his refusal even to attempt a proper adaptation of his source material all the more bewildering. We certainly see enough here to be sorry we weren’t given more. It is significant, too, that all of the advertising for Wizard Of Oz shows Semon in his Scarecrow costume—including in some scenes that don’t appear in the released film. Whether this indicates that Semon changed his mind late about how to adapt the story, or represents a deliberate bait-and-switch, we do not know.

“Well, we’re not in Kansas anymore. I dunno… Utah?”

The sight of the Scarecrow and the Tin Woodsman makes Kruel and his men flee in terror, at which the Wizard and his conspirators have a good laugh…until Kruel starts firing a cannon at them. The three – plus Snowball, who’s just hanging around – surrender, and are arrested.

Kruel accuses them of being the kidnappers and demands that they be cast into the dungeon—which is conveniently located beneath the throne-room, and accessed through a hole in the floor. Dorothy does lodge a protest, but Kynd tells her not to worry her pretty little head over the matter.

(Not that he’s intertitled here, but you can tell from the way she flutters and simpers.)

Dorothy is taken away by her ladies-in-waiting, clearly to try on her new wardrobe or something else that has nothing to do with rescuing her friends, and when she has gone Kynd announces that he must confine “the guilty one” in the dungeon. Larry and Ollie start accusing and counter-accusing, and the upshot is that Snowball gets ordered into the dungeon.

You heard me.

So Snowball resignedly climbs down the huge ladder into the depths of the dungeon, which is run by…pirates. Who carry enormous swords. And have cells full of lions. Don’t ask me.

Up top, Larry, to his credit, refuses to let Snowball suffer alone, and insists on joining him in the dungeon. He marches towards the hole in the floor, head held high…and learns that the pirates have removed the ladder. Naturally.

Decent interpretations of beloved characters, or a vomiting duck? Jeez, tough call…

Topside, Dorothy is crowned (offscreen) and assumes the throne. And what, as queen, does she do for her friends in the dungeon? Nothing. Nada. Not a sausage. She’s too busy signing whatever Kruel puts in front of her, and making goo-goo eyes at Kynd, to bother herself over the unjust imprisonment of the man who loves her and a loyal farmhand. Ah, monarchy! Why wouldn’t you want it?

Meanwhile, Ollie and Uncle Henry have been rewarded for…something or other. Ollie is now the “Knight Of The Garter”, while Uncle Henry, who pirouettes to show off his new togs to us, is – wait for it, wait for it! – the Prince Of Whales.

Oh, what would I not give for a pantomime animal to wander on in and do some capering right about now? Fred Woodward, where are you when I need you!?

The persecution of Larry by Kruel and his minions (including Ollie) will occupy most of the remaining film, yet it is never clear what they think they’ll gain from it. I mean—if Ollie still thinks he needs to eliminate a romantic rival, he clearly doesn’t know Dorothy as well as he should. And while we get that Kruel wants a scapegoat for Dorothy’s “kidnapping”, why Larry rather than Uncle Henry? – who, after all, raised her from babyhood and knows all about her. But instead, Henry is rewarded, while Larry is in constant danger of his life. The pointlessness of all the manic chasing around makes it more than a little tiresome.

Anyway— We are now made aware that the dungeon pirates have a big tub of goop. Gee, I wonder how this is going to end? Larry and Snowball are both threatened with the goop, but it is Uncle Henry who falls through that hole in the throne-room floor and lands in it. And that’s the last we see of him.

Actually, to be fair, we get a good joke here, when the Wizard sneaks into the dungeon and, taking Snowball to one side, suggests to him that, “You can help me to work the skin game on these folks” – and then, in the face of Spencer Bell’s priceless reaction, to add hurriedly that he means put on a skin; a lion skin; a costume. There are, as I have said, real lions in this dungeon; and much comical misunderstanding follows as Snowball in his Cowardly Lion costume is mistaken for one of them, and vice versa.

“You mean I get to be Queen of Oz, and all I have to do in return is sign death-warrants for my family and friends?”

The lion with which Larry Semon interacts here is easily the best actor in the film (and I would very much like to know what they smeared on its mouth, to make it lick its lips like that). Its only real competition comes from Oliver Hardy, who also gets his best moment here, a gleeful reaction shot when he realises that Larry has unknowingly locked himself in with his feline cellmates.

But then they have to spoil it, when Larry and Snowball are threatened by the lions, by resorting to a dark meat joke. Snowball is driven out of the dungeon through a gap in the wall, plunging and rolling down a slope and out of the movie…or so it seems.

In the midst of this confusion, Larry manages to sneak up the ladder and into the throne-room, where he warns Dorothy not to trust Kruel and his followers. This bit of daring provokes an extremely lengthy chase, and the wooden crate sequence I mentioned before.

Earlier, Wikked suggested to Kruel that if he really wanted the throne, he could marry Dorothy. Kruel now acts on that suggestion, and starts putting his superannuated moves on the girl in an amazingly creepy scene.

(Of course! That’s what the Oz stories were missing – sexual harassment! How could Frank Baum not have seen that?)

Kynd interrupts – and where, exactly, has he been all this time? Probably off with the Phantom Of The Basket, if you know what I mean, and I think you do – and a swordfight follows that does not exactly threaten anyone’s memories of Tyrone Power and Basil Rathbone. In the middle of the confrontation, one of Kruel’s minions sneaks up and gets the drop on Kynd, forcing him to lower his sword.

“You’re just lucky I’m Jewish.”

Kruel gloats, and is about to dispatch Kynd when Larry, up on a balcony, pushes a huge vase down onto him. The minion steps up instead, but Kynd is saved again when Larry leaps down from the balcony and takes care of the minion, too.

Kruel is then marched away under guard, and Dorothy, her life, her honour and her kingdom saved, falls into the arms of…Kynd. Oh, she does kiss Larry, but it’s a kiss-off. Because, you know, prince, farmhand, prince, farmhand…

Blech. Give me Princess Gloria and Pon the gardener’s boy any day.

Larry hasn’t much time to contemplate his loss, though, such as it is, because Ollie, Wikked and…someone else…show up, and yet another chase begins.

(This is another frequent criticism of Larry Semon: that he never knew when to quit.)

Larry runs outside and climbs up a water-tower – naturally – so his pursuers start firing a cannon at it – naturally – so Larry picks up a handy rope – naturally – and swings through the air to the other water-tower – naturally – as the first tower blows up behind him. The others start firing their cannon at the second tower, and all seems lost when—

—Snowball shows up, flying a biplane. It has a ladder dangling from it, and Larry is snatched away to safety just as the second water-tower blows up.

Naturally.

“So, about you and that female impersonator—”

“Just rumours.”

Actually, although I say “to safety”, it ain’t necessarily so. As Snowball flies along, Larry begins to climb the ladder. He has almost reached the top when the ladder breaks, and—

—the toymaker’s granddaughter jerks awake with a cry, gathers up her Oz collectibles, and bolts for her bedroom. We think for a minute that It Was All A Dream – or in this case, that It Was All A Nightmare – except that the toymaker opens the volume he was reading from at the beginning of the film and we are made privy to the last sentence: —and Queen Dorothy and her Prince lived happily ever after.

Once her previous suitor had plunged to his gruesome death, that is.

Improbable as it seems, Wizard Of Oz was a mild hit upon its first release, although it did not re-establish Larry Semon’s reputation as he had hoped. He followed it up with another feature-film, a more typical slapstick effort called The Perfect Clown, which also featured Dorothy Dwan, Oliver Hardy, Frank Alexander and Spencer Bell. It was savaged by the critics, and turned out to be a financial failure.

At this point, Oliver Hardy had the good fortune to escape to the Hal Roach lot. There, he was introduced to a gentleman by the name of Stan Laurel—and, perhaps, enjoyed conversations with his new employer about what it was like to make Oz films. Dorothy Dwan found a niche in silent westerns, becoming a favourite actress first of Tom Mix, then of Ken Maynard. Larry Semon, meanwhile, retreated to the world of two-reelers, where he struggled on for a time but only succeeded in repeating himself more than ever. Consequently, audiences increasingly shunned his work.

“There’s no place like a water-tower…there’s no place like a water-tower…”

By the end of 1926, between debts, lawsuits and crumbling popularity, Semon was in real trouble. He began taking any work that offered, from whoever offered it; and a glimmer of hope dawned for him when he received good notices for an effective character performance given for Josef von Sternberg in Underworld. However, it was too little, too late, and he declared personal bankruptcy in March of 1928.

Larry Semon’s health was unable to withstand this constant strain. It was reported publicly that he had suffered a nervous breakdown, but he was next heard of in a Californian sanatorium that specialised in the treatment of tuberculosis. It was there that he died in October 1928, at the age of only thirty-nine, leaving a twenty-four-year-old widow.

A certain mystery surrounds the death of Larry Semon – various details do not add up – so that some people believe that he may have faked his own death in order to escape his creditors, although little hard evidence supports this theory.

In the long run, Larry Semon’s Wizard Of Oz did nothing to hinder the tag “box-office poison” being increasingly applied to cinematic adaptations of Frank Baum’s stories—although certainly Baum himself could in no way be blamed for this one. It was some time before anyone would again tackle the task of bringing Oz to the screen, at least in any serious way. A scattering of short films, mostly animated, appeared throughout the early 1930s; and then, in 1938, the rights to Frank Baum’s first Oz novel were purchased by MGM…and unlike the Larry Semon version of the tale, we don’t need anyone to tell us how that story ends.

Hey, a happy ending!

Written, directed by, and starring the same person… very often a sign of a film that may be great or terrible, but is unlikely to be mundane, because nobody was in a position to tell him to tone it down a bit.

You’d think the civil service of Oz would have a filtering programme for people whose names are “Wikked”, “Kruel”, “Vishuss”, “Eville”, etc.

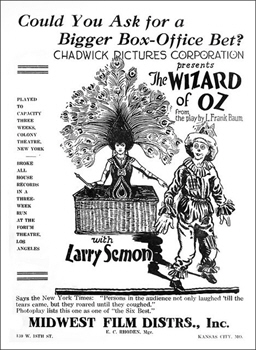

“Could you ask for a bigger box-office bet?” Well, in the sense of “gamble”…

I am now suffering from Hat Envy of the Wizard. My word, that’s gorgeous.

LikeLike

Apparently, nobody realized that ‘box office poison’ referred to BAD adaptations of the Oz novels. The Judy Garland one does at least keep within spitting distance of the original.

LikeLike

I’ve noticed that some films have a form of “anti-suspense” where you’re not thinking, “Is he going to escape?” but “How long is this going to take?” Sounds like Larry Semon might have done that for comedies.

LikeLiked by 1 person

“G. Howe Dark” was, sadly, one of the more gentle supposedly humorous stereotypical names laid upon Black actors of the time. There was, of course, Stepin Fetchit, but poor Willie Best may have had it worst. He was frequently billed as “Sleep ‘n’ Eat.”

LikeLike

That one is at least subtle enough that I’ve known people to miss its significance; the others…not so much. 😦

LikeLike