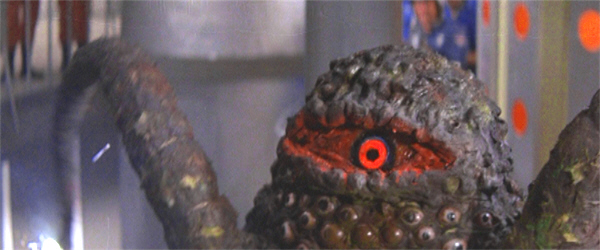

“These creatures could be developing in any part of the station where a drop of this substance can reach any kind of energy!”

Director: Fukasaku Kinji

Starring: Robert Horton, Richard Jaeckel, Luciana Paluzzi, Bud Widom, Ted Gunther, Robert Dunham, David Yorston

Screenplay: Charles Sinclair, William Finger and Tom Rowe, from a story by Ivan Reiner

Synopsis: A huge rogue asteroid, known as Flora, is found to be on a collision course with Earth. At Space Central, Cape Kennedy, General Jonathan Thompson (Bud Widom) calls Commander Jack Rankin (Robert Horton) to his office. Explaining the situation, Thompson tells Rankin that the only way of saving the Earth is for a crew to fly to the asteroid and blow it up. Despite having tendered his resignation from the space program, Rankin immediately volunteers. Thompson tells him that his mission will leave from the space station Gamma 3, and warns him that the station is under the command of Vince Elliott (Richard Jaeckel). Rankin and Elliott were once best friends, but fell out after Rankin reported Elliott for what he perceived to be his unfitness for command. On Gamma 3, Elliott’s fiancée, Dr Lisa Benson (Luciana Paluzzi), is disturbed to learn that Rankin has been given command of the mission ahead of Elliott. When Rankin arrives, Elliott tells him that scientist, Dr Halverson (Ted Gunther), will be joining the mission, then volunteers himself. Once on Flora, Rankin divides the party into three teams, each to drill into the asteroid and plant an explosive device. Halverson discovers a strange green substance that is clearly alive and, thrilled by his discovery, collects a sample. Rankin is contacted by General Thompson, who gives him the grim news that Flora is accelerating, and that to save the Earth, the detonation time has been moved up. The men must therefore leave immediately. When Rankin shows himself willing to leave the tardy Halverson behind, Elliott insists that they wait—only for Rankin to remind him that he made that mistake once before. An excited Halverson comes running up, but Rankin throws away his discovery. Unnoticed by the men, one of the crew’s uniform is spattered with the green substance. The ship is at full speed when the explosives detonate and, while it is badly hit by the shock-force and debris, everyone survives. Arriving on Gamma 3, the crew is greeted by a wild celebration. Lisa rushes into the quarantine area to greet Elliott, but is rebuked by Rankin, who points out that they haven’t been decontaminated. Rankin then puts Halverson in charge of this process, and orders him to go through the routine three times despite Elliott’s objection that they can’t spare the necessary equipment for so long a time. His arm having been injured on the journey back, Rankin goes to the infirmary. As she treats him, Lisa tells him that he nearly destroyed Elliott by reporting him to the board of inquiry. Rankin defends himself, standing by his belief that Elliott is not command material. To celebrate the destruction of Flora, Gamma 3 throws a party. Rankin dances with Lisa, and accuses her of still being in love with him. Suddenly, terrifying screams echo through the station. A technician who was decontaminating the mission suits is found dead, electrocuted; much of the unit’s electrical equipment is wrecked, and a small sample of the green substance from Flora is discovered nearby. While the station is being searched, another crewman is mysteriously electrocuted. As Rankin and Elliott inspect the body, they are urgently summoned to the main power room where they are greeted by an incredible sight: a green, one-eyed, tentacled creature that is giving off a strong electrical charge…

Comments: The first ever Japanese-American co-production in film history was the result of a collaboration between MGM and the Toei Company. It is not altogether surprising that the outcome of this unlikely partnership was rather…odd. However, the oddest thing about it may be that its antecedents were Italian.

By 1968, a Japanese-American co-production was a step that made economic sense. Japanese science-fiction films produced by Toho Studios had been exported to America from the mid-50s onwards, to great popularity and financial success; and while the early films were often re-cut and/or had subplots featuring Caucasian actors added, to (supposedly) make them more appealing to American viewers, as more players entered the game – namely, Daiei, Toei and later Shochiku – it became more common to write non-Japanese characters into these science-fiction films, in anticipation of their export. Sometimes this simply meant rounding up any American actors (and non-actors) who happened to be in Japan and giving them supporting parts, but eventually it became a more organic aspect of the film-making process. One of the various consequences of this shift in procedure was a sudden upsurge in blonde leading ladies in Japanese productions, even to the extent – as in 1966’s Terror From Beneath The Sea – of placing an interracial relationship front and centre.

Terror From Beneath The Sea was co-produced by Walter Manley, the producer-distributor who, in partnership with writer-producer, Ivan Reiner, operated RAM Films during the 1960s. In 1966, Manley brokered a deal which saw MGM supply partial funding for the production of I Criminali della Galassia (Criminals Of The Galaxy), these days better known as Wild, Wild Planet. Manley and Reiner produced the film, with their associate Joseph Fryd; while Reiner shaped the story and, with his colleague William Finger (the co-creator of Batman!), contributed to the screenplay.

The production was originally intended for television, but MGM were sufficiently impressed with the film, and with director Antonio Margheriti’s way with a low budget, to (i) release it to cinemas, and (ii) ask for more of the same. In a ridiculously brief period of time, in fact within a mere three months, Manley, Reiner and Margheriti served up I Diafanoidi Vengono da Martei (The Diaphanoids Come From Mars / War Of The Planets), Il Pianeta Errante (The Wandering Planet / War Between The Planets / Planet On The Prowl) and La Morte Viene dal Pianeta Aytin (Death Comes From Planet Aytin / Devil Men From Space / Snow Devils).

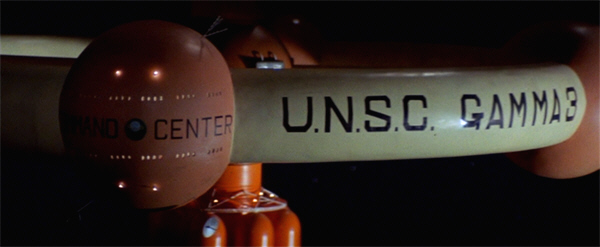

All of these films were set on and around an orbiting, spoked-wheel-shaped space station called ‘Gamma I’, such that the four together are now often referred to as the ‘Gamma I Quadrilogy’.

It isn’t quite clear what happened next. It seems that plans were made for a fifth Italian-produced film, but instead – though again funded again MGM, and still co-produced by Walter Manley and Ivan Reiner, and co-written by Reiner and William Finger – the film was shot entirely in Japan, at Toei, with a Japanese director, special effects team and crew, and a Caucasian cast—and with the name of the space station changed to ‘Gamma 3’. Originally called Ganmā dai 3-gō: Uchūdaisakusen (Gamma No. 3: Space Division) in its country of origin, in the west the film is known – and by some of us, adored – as The Green Slime.

On the back of the unexpected critical and popular success of Black Lizard, the man tapped to helm the co-production was Fukasaku Kinji. Fukasaku’s immediate idea was to make The Green Slime an allegory of the Vietnam War: a proposal quickly shot down by MGM, who didn’t want any politics interfering with the marketability of their monster movie.

(It is possible, however, that the director got in a few licks behind his paymasters’ backs, as we shall see.)

Meanwhile, former Toho employees, Yukio Manoda and Akira Watanabe, who learned their trade under Eiji Tsuburaya, were put in charge of the special effects. The rest of the crew were Toei regulars.

Constructing the predominantly American cast presented something of a challenge. Though initially MGM indicated that “big stars” would be appearing in their breakthrough co-production, in the end they settled for familiar faces in Robert Horton and Richard Jaeckel, with former Bond villainess, Luciana Paluzzi, making up the third point of the film’s love triangle (and adding to the Italian feel of the enterprise).

So much for the “names”. Robert Dunham, a part-time racing-car driver who operated an import / export business in Tokyo while also forging something of a film career on the basis of his fluency in Japanese, was cast as the competent Captain Martin. Ted Gunther, who had already played bit-parts in a few Japanese films (including Gorath) was promoted to the full-blown supporting role of Dr Halverson. Bud Widom, a stalwart of the American Forces Radio and Television Service, was cast as General Thompson. William Ross, the film’s associate producer, who also served as an on-set translator, has an uncredited bit-part as one of the station crew.

Beyond that, however, it was simply a matter of who they could round up. Most of the film’s tiny female roles were filled by American models working in the Tokyo fashion industry; while the numerous red-shirt roles were taken chiefly by servicemen from an American military base.

(There are one or two other familiar faces in the film, but we’ll consider those in context.)

The Green Slime premiered in both Japan and America in December of 1968—although each country got a different version of the film. Ironically, given the long American history of cutting Japanese science-fiction films, the Japanese version of The Green Slime is some thirteen minutes shorter than its American counterpart, cut down to focus on the action scenes.

Conversely, the Americans replaced the film’s typically serious and rather martial theme-music composed by Tsushima Toshiaki with—

—this:

God bless ’em, every one.

With all due apologies to Tsushima Toshiaki, this mindbogglingly marvellous bit of psychedelic kitsch is enough on its own to secure The Green Slime a slice of immortality. It was written by Charles Fox – who also wrote the theme-song to Barbarella, but is probably better known for his TV work, which included the themes for Happy Days, The Love Boat and Wonder Woman (“Get us out from under, Wonder Woman!”) – in collaboration with Richard Delvy, aka Richard Delvecchio, one of the pioneers of 60s surf-music, who got his start as a vocalist-drummer with The Bel-Airs, became a composer, arranger and producer, and hit it big when he secured the rights to the Surfaris’ “Wipe-Out”. Though a shortened version of the song plays over the film’s opening credits, the full-length version offered in this clip was, astonishingly, released as a 45rpm single. (Kids, ask your parents!)

It could be reasonably argued that this theme-song is a better fit for the film overall than Tsushima’s solemn scoring. There are, as I have already suggested, many odd things about The Green Slime. It is by no means alone in the field of science fiction in being, evidently, incapable of imaging THE FUTURE in terms other than those in existence at the time of its production; the Italian films which preceded it suffer from exactly the same, admittedly often amusing, shortcoming; yet its military-installation-cum-discotheque space-station seems even more than ordinarily “off”.

The film’s structure is also strange—although that said, it is impossible not to admire the way it turns the entire tortuous two-and-a-half hours of Armageddon into a throwaway opening act, a mere set-up for the main action. And then, having started out looking like an adventures-in-space film, The Green Slime abruptly mutates into a monsters-in-space film, of the kind pioneered by It! The Terror From Beyond Space; but (rather like Contamination’s overkill re-working of Alien’s chest-burster scene) instead of giving us one convincing – or at least, well-hidden – monster, it gives us a swarm of adorably unconvincing ones which run around in plain sight. And, perhaps most puzzling of all, the character presented to us in the position of “hero” is a man whose leading personality trait is his unrelenting dickishness.

I don’t think we can much blame the Japanese for cutting out what passes in The Green Slime for “human interest”, which amounts to an ongoing pissing-match between Robert Horton’s Jack Rankin and Richard Jaeckel’s Vince Elliott – mostly over their disparate command styles, but with Lisa Benson a further bone of contention – which invariably end with Elliott getting, uh, soaked. From the moment these two erstwhile best friends are reunited (and it is almost as hard to believe they were ever friends as it is that Lisa was, and is, attracted to Rankin), the storyline settles down into a cyclic pattern of Ranking giving an order, Elliott countermanding it, Elliott being proven wrong and Rankin being proven right; repeat ad infinitum.

The difficulty for the viewer in all this is that – to put it mildly – Rankin is a smug, smarmy, self-satisfied butt-wipe, intolerable even by the exasperating standards of the Designated Hero©.

So dominating is Rankin’s obnoxiousness is that we are forced to ponder how the audience was intended to take him. Of course, it’s quite possible that the film-makers didn’t see what we see: that Rankin was simply meant as the standard no-nonsense, by-the-book, get-the-job-done type, but that by some film-making twist – possibly Robert Horton’s inability to project authoritativeness rather than someone having a hissy-fit – the film was left with a walking contradiction.

Or—perhaps this was intentional—and insidious. We eventually learn that Rankin and Elliott fell out over the former reporting the latter over what he considered incompetence in command, after a mission in which Elliott lost ten men in an attempt to save one. Again and again, Elliott’s “weakness”, his tendency to risk lives to save lives, is held up against Rankin’s hard-line command style and found wanting; again and again, Rankin berates Elliott for it—even as Rankin himself is getting people killed—until the disconnect between what we’re told and what we see cannot help but give the viewer pause.

Now—I’m perfectly prepared to concede that being a nice guy is not necessarily the best qualification for command (though you’d like to see some concern for his men shown by a commanding officer, surely?); but at the same time, no-one’s ever going to convince me that being a snarling, petulant bully who actively causes conflict and turns everything into a dick-measuring contest qualifies someone for the job either.

But you know— The more the film dwells upon the childish back-and-forth between the well-meaning but ineffective Elliott and the effective but destructively tunnel-visioned Rankin, with the ordinary servicemen caught between them and the body-count rising, minute by minute—the more I can’t help wondering whether Fukasaku Kinji didn’t manage to sneak his Vietnam allegory in there after all…

The Green Slime opens with an attempt at a spectacular establishing shot, as a gliding camera first finds the planet Earth, before pulling back to show us Space Station Gamma 3. Instead, the film immediately gets itself into trouble. It is both a major shortcoming and much of the charm of The Green Slime that its models are never less than almost embarrassingly apparent. Part of this is due to the way the film is lit and shot, which really leaves nowhere for them to hide. Yet the overall model-work itself is disappointing, lacking the attention to detail that marks the best of Toho. Everything looks exactly like what it is, i.e. a plastic toy.

Gamma 3 is going about its normal functions, reporting on the weather, the position of satellites and probes, and astrophysical phenomena to the Cape Kennedy (!) Space Center…where we immediately notice something odd: the complex is emblazoned with “UNSC”, which presumably stands for United Nations Space Command; but don’t waste your time waiting for the non-Americans to show up. (Spoiler alert: there’s one – count ’em! – one.)

Inside the complex – as indeed is the case on Gamma 3 itself – we discover that in this far-flung future (a future which the film never dates for us, by the way), the female of the species has not yet managed to break through the glass ceiling. There are a few women working for the space program, but in extremely limited roles; while (with one exception) all the command positions, and all the military postings, are filled by men. The Green Slime takes pains to inform us of The Way Things Are In The Future in the very first shot involving a female character—who is introduced to us via a camera-shot up her skirt.

“I want to say one word to you, Benjamin. Just one word…”

Female Tech (who gets no lines, of course) carries a printed report to her supervisor, who offers the following deeply profound observation:

Supervisor: “Same old garbage. Nothing exciting even happens around here.”

And wouldn’t you know it!? – the words are barely out of his mouth before one of the command unit’s monitors goes berserk. As its reception clears, something unusual shows itself on the monitor; something which, upon magnification and examination, proves to be a rogue asteroid, which is—

—hold onto your hats; you won’t see this coming!—

—on a collision course with Earth!!

And—cue:

(Oh, go on! You know you want to…)

Calculations of the asteroid’s trajectory and speed are reported to General Thompson, who observes grimly that their only chance is to blow the asteroid to pieces; not a great chance, given the limited time at their disposal. (How the asteroid got this close to Earth without being detected – by Cape Kennedy or by Gamma 3 – is never addressed.) Simultaneously, Thompson receives word that Commander Jack Rankin is waiting to see him.

This provokes an exclamation of surprise from one of the General’s underlings, who explicates helpfully, “But he’s tendered his resignation!”

While he waits for the General, Rankin gazes at a photograph of himself and Thompson with a third man, who we learn is Commander Vince Elliott. “Rankin and Elliott: best space-team we ever had!” reminisces the General. “For a while there,” agrees Rankin, “until I ruined it.”

This is the only moment in the entire film in which Jack Rankin concedes that he is anything less than perfect—so enjoy it while you can, folks.

The General fills Rankin in on the rogue asteroid, Flora, and tells him that there are less than ten hours to go before, if nothing is done, it will hit the Earth. Explaining that blowing the asteroid up is their only option, he adds that in his mind, there’s only one man with the necessary experience to head the mission; though of course, “He’d have to volunteer…”

Which – of course – he does. Thompson gives him his orders, clarifying that until the job is done, Rankin will be in charge not only of the mission, but of Gamma 3…which is under the command of Vince Elliott. “My lucky day,” observes Rankin.

(We’re left to wonder how he could not already have known that.)

Tacky sexism of…THE FUTURE!!

As Rankin turns to leave, Thompson wishes him good luck and gives him a thumbs-up. Rankin returns the gesture, rather dramatically—in what sadly will prove to be a motif which grows ever more insufferable as the film progresses.

(…not least because it kinda makes me want to re-watch Megaforce…)

As Rankin and his crew are blasting towards Gamma 3, word of their mission spreads through the station. Captain Martin, Vince Elliott’s 2IC, reacts in a way which suggests that he, at least, is not happy about the new command arrangements. However, Elliott moves quickly to quash any hint of dissent.

But Martin is easier to silence than Dr Lisa Benson, Elliott’s fiancée—and Rankin’s ex-girlfriend. Sigh. She waxes indignant about Rankin being placed over Elliott’s head—and then offers, unprompted, the assurance that Rankin no longer means anything to her.

Sigh…

By the way, you’ll have to take it from me that Lisa’s surname is Benson: though she is, presumably, Gamma 3’s Chief Medical Officer (in fact, she seems to be the only doctor on board, though there are numerous nurses), no-one ever addresses her by her title, or even by her qualification; she is simply “Lisa” to each person who speaks her name.

The ship carrying Rankin and his crew docks on Gamma 3 (which seems to be a lot bigger on the inside than the outside), and Rankin is greeted by Elliott, who volunteers for the Flora mission—and also informs Rankin that his orders have changed, to include scientist Dr Halverson and his assistants. Rankin isn’t the least bit pleased about the latter, and shows it, but only orders the newcomers to get ready for their immediate take-off.

“God, I look good…”

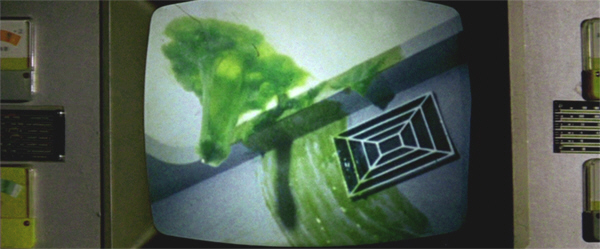

Once on Flora, the crew splits into three, each to place an explosive device; while Halverson’s attention is immediately attracted by patches of green, glowing goop. One patch of it is actually pulsing—which causes this [*cough*] highly-trained scientist to let drop the specimen he’s already holding, which splatters all over his equipment. When he looks back from poking and prodding the second one, the first one has grown up over the monitor on which it landed, and seems to be almost seething with life…

The devices planted, the other men are forced to abandon their equipment and run for it when they can’t start their buggies; furthermore, green goop has grown up over the wheels. They gather at the ship, where Space Command is letting Rankin know the bad news: Flora is accelerating, and detonation must be accelerated likewise—which significantly reduces the chances of the men outrunning the blast.

Rankin reports this to the others, ordering them onboard immediately—only Halverson isn’t back. Rankin shows himself perfectly willing to leave the scientist behind, which Elliott protests, demanding another couple of minutes:

“You’ve made this mistake once before,” Rankin throws at him.

Before the confrontation can go any further, Halverson rushes up – so much for that – brandishing his specimen jar with glee and uttering that all-time favourite scientist’s cry, “It’s alive!”

Rankin, unmoved, orders him to get rid of it—and, when he begins to argue for his “major discovery”, snatches the jar from his hands and smashes it on the ground, snarling as he does so, “You can’t bring it with you!”

Uhhh…why?

Because Jack Rankin says so, evidently. Which is the reason Jack Rankin gives for everything.

We might stop here to consider – which is more than Rankin ever does – why Space Command sent the scientist along on this mission in the first place. It couldn’t have been to, oh, I don’t know, collect specimens, could it??

“Honestly, Vince—all that mind-blowing, loin-destroying, screaming hot sex Jack and I used to have never crosses my mind these days…”

Anyway, everyone rushes onto the ship—no-one noticing that one of the crew has a splash of goop on his space-suit…

The ship accelerates away from the asteroid, but not fast enough to suit Rankin, who orders top-speed. The pilot objects that the ship will break apart, and Elliott that they will. Rankin repeats the order and, when the others hesitate, throws himself to the front of the ship and slams forward the speed controls. The ship lurches forward, Rankin is thrown back – gashing his arm in the process – and the crew writhes under the almost intolerable G-forces.

Then Rankin orders the force-shield activated—I dunno, might have been an idea to do that first, as the pilot cannot fight forward to throw the switch. Only Jack Rankin is man enough for that! – he struggles to the front, G-forces be damned, and activates the shield just in time to protect them all from the combined shockwave and debris of Flora’s explosion.

Wouldn’t it have been easier to send Rankin on up his own?

While I say that— What it is impossible to overlook in this sequence is that there was no specific need for Rankin to be there at all. No specialised skills were involved, no decisions requiring specific experience. And if they hadn’t had to wait for Rankin, then the mission to blow up Flora could have started much earlier, significantly reducing the crew’s danger, while in no way impacting its success.

If I were Vince Elliott, I’d be just a little pissy about that…

But of course, this isn’t the only thing that would have been different if Rankin hadn’t been there. Without the smashing of Halverson’s sample, the green goop would (presumably) have made it back to Gamma 3 safely contained, instead of as an unseen hitchhiker; and while it (presumably) would have been subject to various tests which may or may not have had unfortunate consequences, it wouldn’t have been triple-irradiated, as per Jack Rankin’s orders.

“Maybe I should have had that flu shot after all.”

Which means that everything which happens from this point on is entirely Jack Rankin’s fault.

Don’t hold your breath waiting for the film to admit it, though.

The men arrive back on Gamma 3 to a heroes’ reception. In her excitement, Lisa breaks protocol and enters the containment area. Rankin immediately reprimands her (for once he’s right: a doctor breaking quarantine? – sigh) but his next move is more problematic, as he puts Halverson in charge of the decontamination of personnel and materials and orders him to run the process through three times. When Elliott objects that they can’t spare the equipment for that long, that it will interfere with the operation of the station, Rankin reminds him that he is still in charge.

“I suggest you bone up on your regulations,” he snarls at Elliott, who gives him a look which suggests he’s contemplating a retort that will also feature the words “bone up”. He says nothing, however, and the men – including the one with the splashed suit – pass through the decontamination chamber. Rankin then takes himself and his gashed arm down to the infirmary, where a nurse offers to get a doctor for him. “Don’t bother,” he replies abruptly and strides off—leaving the nurse gazing after him with an expression on her face we might justly interpret as, “What a DICK!”—

—and OH MY GOD IT’S KATHY HORAN!!

Yes, indeed it is: I addressed Ms Horan’s Japanese film career with respect to War Of The Insects, made the same year as this, and I was delighted to spot her here, playing a nurse, and also showing up in the party-scene (one of the film’s highlights). She’s not the only familiar face lurking amongst the station’s nursing staff: another bit-player, sadly without lines, is Linda Miller, who the year before was the female star of King Kong Escapes: one of those “blonde leading ladies” I was referring to, in a film which, given its production circumstances, could reasonably challenge The Green Slime for the title of first co-production.

“I just want to breed vast numbers of insects that drive people mad…after I’ve had a few chammies…”

Rankin zeroes in on Lisa. She acts for all of us and wipes his arm with something that really, really stings, before scolding him for his inflexibility and – again unprompted – assuring him that’s “it’s all finished” between them.

Sigh.

Rankin is just about due to depart, but first Gamma 3 throws a PAR-TEY, in that inimitable the-future-mutates-into-1968 way, as champagne corks pop, and dancers groove. Elliott’s announcement of his and Lisa’s imminent wedding prompts Rankin to haul her out on the dance-floor. At this point we learn details about the falling-out between Rankin and Elliott; and though Rankin conceded to General Thompson that he was the one who ruined their friendship, to Lisa he stands by his reporting of his friend, though it meant he had to face a Board of Inquiry.

A Board of Inquiry which, presumably, exonerated Elliott, since he now holds the rank of Commander and is in charge of Gamma 3; which, in other words, thought Jack Rankin was wrong. Again the film fails to see it like that…

(Though I suppose if you wanted to carry the analogy through, you could see Elliott as the embodiment of the Peter Principle.)

Rankin then dismisses Elliott as a nice guy but not command material, before informing Lisa that what she feels for Elliott isn’t love, but pity. “You’re still in love with me,” he adds, pulling her close enough that he can rest his crotch on her, and smirking at her in a way that, honestly, made me feel rather nauseated.

What I wouldn’t give right about now for some monsters on the rampage…

Somewhere away from the party, a random minion is putting the suits from the mission through yet another cycle of irradiation. In response, something green and oozy begins to slide out from between the layers of clothing…then to grow…then to glow and pulsate…

White People Dancing of…THE FUTURE!!

Some time later, the minion investigates a strange noise, and finds the door of the radiation unit buckled and damaged. He makes the mistake of opening it…

An alarm sounds as the minion’s agonised scream interrupts the party. In the laboratory, various electronic equipment is found wrecked and burned, with its wires hanging out; while the unfortunate minion, too, is found wrecked and burned: electrocuted, according to Lisa. Elliott then notices a glob of goo in the chamber, which Halverson comments looks like the material on the asteroid, only it isn’t moving.

“That’s your responsibility!” snarls Rankin.

(Uh, actually…)

A full search of the station is set in motion. In the command centre, one of the monitors is out of order; and, when its operator requests that a check be made on its power-source, another minion gets a nasty shock. Literally. He screams as a tentacle drops across the back of his neck…

Electronic equipment all over the command centre begins to malfunction, as Elliott is called to C Block. From this point, there will be much movement around the station on metal carts that are nearly as wide as the corridors, and honestly don’t seem to move much faster than the men could do on foot. Be that as it may, Elliott and Rankin have only just arrived at the scene of another electrocution than they are summoned to the main power-block where, next to a high-powered generator, a strange, green, tentacled, almost man-sized figure thrashes on the floor.

Rankin has barely glanced at the creature before he is training a laser-rifle on it—which of course prompts an hysterical intervention from Halverson. Say it with me, now!—

Halverson: “Stop! Don’t kill it! Try to save it! It’s a magnificent discovery!”

“That had better be your service pistol…”

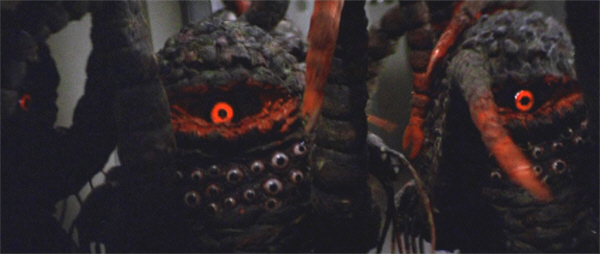

Well, we know by now how the game is to be played: Elliott sides with Halverson, and it all goes ’orribly wrong. The gas-guns fired in an effort to subdue the creature seem to stimulate it instead. It bounces up and comes charging, blinking its single red eye (it does have other eyes, but they appear to be merely decorative), waving its tentacles, and making noises like a chew-toy on acid.

SQUEEEEEEEEEE!!!!!!!!!!!

Yes, it’s true: not since the pyjama-clad starfish-aliens of Warning From Space have I so desperately wanted to run up and give something a hug…though I guess in this case, that wouldn’t be such a bright idea…

Like so many Japanese monsters, the Green Slime are both perfectly ridiculous and strangely effective. The fact that each and every one of the creatures – and there will be hordes of them on the loose before long, I am happy to say – is someone in a suit, and therefore fully present on the set and able to interact with the actors, gives them a reality than even the dysfunctional absurdity of their design can’t completely undermine. And it is to the credit of the cast, too, most of whom weren’t used to dealing with this sort of production, that everyone manages to keep a perfectly straight face when confronted with rubbery polyps on the rampage.

The creature breaks free of the nets and does damage with its tentacles, fatally wounding one of the men and lashing Elliott across the shoulder. Rankin then springs forward and fires at the creature, which turns and flees. Finally they chase it down a dead-end corridor.

Rankin wastes no time rubbing in Elliott’s face the failure of the attempt to catch the creature—although the fact that his own efforts to stop it ended in the deaths of two more men goes unremarked. He announces himself in command of the station, and institutes a fire-at-will policy…which turns out to be the worst thing anyone could have done, not that the film ever acknowledges it…

SQUEEEEEE!!!!!!

As a downcast Elliott heads off to the infirmary, Halverson notices a green material on the floor, and collects a sample.

You know—I’m sure Halverson is a very good scientist, really, but I wish he’d stop trying to pick up liquids with his forceps.

Halverson quickly determines that the material is blood—and is soon in a position to demonstrate to Rankin and Elliott what happens when the substance is exposed to a power-source: namely, that its cells divide, and grow, and eventually spawns new creatures; creatures which can, Halverson adds, can both absorb and discharge energy.

Rankin: “You mean this stuff reproduced itself inside the decontamination chamber!?”

Where you ordered three cycles of irradiation? Yuh-ha!

Rankin sets in motion a new sweep of the station, at the same time revoking his fire-at-will command. Which is to say, he revokes to the men in his hearing—but without bothering to make a general announcement over the P.A. system…

Hey, Jack: that wouldn’t be a mistake on your part, would it?

Didn’t think so.

In the infirmary, Lisa and Nurse Kathy decide to subject a wounded man to “The Analyser”. Lisa swings the giant computerised scanner out of its wall-socket, but notices immediately it is behaving oddly. She glances into the alcove in which it is usually stored—

—and finds it occupied by a creature.

“And as soon as I’ve picked up all this blood, I’ll get that needle in a haystack found…”

“Get everybody out! Don’t ask any questions!” says Lisa, as if the others can’t see the red claw-tipped tentacle thrashing around behind her. To the sound of much hysterical screaming – for qualified Space Nurses, these girls sure lose their heads easily – the patients are hustled out, while Lisa and one or two others try to hold the creature at bay—with a metal bed. Martin and a team respond to an alarm signal and, of course, start blasting away with their laser-guns, ensuring that much green blood is shed.

Rankin, Elliott and Halverson arrive, just too late; and the former two, via much judicially wielding of metal objects, manage to trap the creature in the isolation ward. Even at this desperate moment, Rankin can’t help being a dick, snapping, “Get the door, Vince!”, like Elliott isn’t even capable of thinking of that for himself. Displaying heroic self-control, Elliott somehow refrains from retorting, “You get the door!” and/or sticking his tongue out.

Another of the putt-putt carts comes tootling up, this one carrying a monitor via which the men can see into the infirmary. To their horror, they see the wounded creature using its own tentacles to cauterise its injuries.

Meanwhile, all around it, the spilled green blood, which has already grown into a solid field of slime, is – creeping and leaping – gliding and sliding – across the floor, and all around the walls—

Well, it is.

And among other things, it’s getting into the vents. We also get a rather adorable close-up of baby critters being literally spawned from a puddle of goo. Awww…

(Actually, though it is executed simply enough, by inverting the image, these shots of the slime spreading around the station is one of the film’s more convincing effects.)

Elliott grabs the microphone and orders all power cut to the infirmary. “Smart move, Vince!” approves Rankin…the patronising arse.

Beware of the—uh, green slime!

From this point, I am delighted to say, The Green Slime settles down into almost non-stop monster-scenes. Again and again, we are treated to the sight of whole swarms of them beetling their way along the corridors, waving their tentacles and squeaking like a flock of rubber-duckies. The things are so gosh-darn cute that the human characters seem meaner and meaner, in their efforts to stop them. (And more and more incompetent, in their inability to do so.)

As Rankin gets on the line to Space Command, explaining that Gamma 3 has been placed in quarantine, and why, Elliott explains their plan to confine the creatures to a small section of the station to the men: they will shut off the power to C Block, and use a searchlight on one of the metal carts to lure them into a room where a generator has been set up, offering it as bait. Above all, Elliott stresses, they have to keep the creatures away from the main power unit.

While the trap is being set, C Block has to be evacuated—including Lisa and her patients, who just got settled back down after their first evacuation.

As the station darkens, Rankin and his squadron switch on their search-lights. The plan works, with the creatures shuffling towards this source of energy; so eager to get to it, several of them waddle straight past Elliott and his men without taking any notice. The searchlight-cart begins to back away—just as crashing noises and hysterical screaming are heard coming from the temporary infirmary. Sure enough, some of the creatures have burst in upon the patients – who really aren’t having a good day – though it isn’t clear why they have. Maybe this area is a short-cut for them? – or maybe, being monsters after all, they saw some girls, and, you know…

(Lisa gets a clear Heroine’s Death Battle Exemption© here, as one of the creatures clearly whacks her on the back of the head with a tentacle.)

Rankin comes rushing in and tries to draw the creatures away with a torch, but suddenly finds himself trapped as one lurches up behind him. To extricate himself, Rankin—

Aww… Polyps-ey!

Oh, whoa, whoa, whoa! I am not having that, nuh-UH!!

—because damned if Rankin doesn’t resort to the patented James Tiberius Kirk Barrel-Roll.

{*seethe*}

Sir, I knew James Tiberius Kirk. James Tiberius Kirk was a friend of mine. YOU, sir, are no James Tiberius Kirk.

{*seethe*}

Anyway, with the room free of creatures, Lisa and the nurses are able to transport their patients out of C Block; Lisa closes the air-lock behind them.

Rankin, meanwhile, is in dire peril – yay! – as he finds himself caught in the middle of a three-way convergence of creatures. But as it seems he hasn’t a chance—Elliott comes rushing up, light in hand, and orders him to douse his own torch so he can lead the creatures away.

Oh, Vince, Vince, Vince… You really are a doofus.

And the bastard isn’t even grateful. As soon as he rejoins his squadron, he snaps impatiently at Elliott, “Back here! C’mon!”, as if he were just messing around to no purpose.

But the plan works, with the creatures locked away with the generator—all except the one in the isolation ward. Oops!

The men agree that the door won’t hold. Martin suggests using the cart to brace it closed, but gets a dose of the Elliott treatment for his trouble, as Rankin snaps at him, “That won’t help much!” Like Nurse Kathy before him, Martin responds with an eloquent look…

“I’m in perfect physical condition! Yay, me!”

Instead, Rankin proposes shutting the creature into C Block via the other air-lock door. By this time the screenplay isn’t even bothering to come up with a reason for Elliott to object to Rankin’s plan: he just does, so he can get shot down and then exchange a sad look with Martin.

Rankin’s announcement of the new arrangement brings Halverson running, wailing about his work, his notes. Of course Rankin doesn’t care. But then Halverson doesn’t care that Rankin doesn’t care, and goes plunging along the corridor into his laboratory. Martin is sent to retrieve, “That idiot”, just as the stray creature comes crashing out of the isolation ward.

And then the other trapped creatures smash down the door that’s confining them and also come charging into the corridor! With the generator still running it isn’t clear why they would do this, but the more the merrier, I guess.

Everyone retreats backwards at a rate of knots, a process much complicated by the fact that (as mentioned) the metal carts are nearly as wide as the corridor, forcing people to squash themselves back against the walls they pass. The carts are, in fact, leaving the scene with undignified haste—which causes a problem when a slightly disoriented Halverson steps out in front of one.

Well. In my original review of The Green Slime, I commented of the scene which follows, “I don’t know how this masterpiece of confusion plays in widescreen, but in pan & scan, it’s hilarious.” Now that I can see it in widescreen, I’m delighted to report it’s no less hysterical. We simply have a better view of things as the first cart swerves desperately to avoid hitting Halverson, hits a second cart instead, which itself swerves out of control, swooping right and left and nearly wiping out the entire squadron of men—one of whom, as he flings himself out of the way, accidentally trips the air-lock catch with his gun, trapping Halverson on the slimy side of it. It nearly traps Rankin, too, but he saves himself via, sigh, another barrel-roll.

Hands in the air—

I must confess, I’m totally confused about the geography of the next scene, which shows us the team trapped between two air-lock doors, one of them jammed by a crashed cart. The dialogue suggests that shifting the cart (which they try to do) will somehow help Halverson—seen and heard in his terror on one of the monitors behind the other door. Eh? Of course Elliott insists on opening the other door, of course Rankin orders him not to, of course Elliott does it anyway—although not until Rankin has threatened to shoot him, he has turned his back defiantly on Rankin, and Lisa has placed herself in the line of fire.

And of course it’s too late – Halverson is dead, fried – and of course the creatures come charging out into the corridor…

And how does Jack Rankin respond? By shooting them and making them bleed…and ignoring Elliott when he reminds him that this isn’t such a good idea.

Everyone then runs away, so I guess they got that cart free when we weren’t watching. Rankin orders Martin to shut the second air-lock, trapping the creatures again—right next to the inflammables store.

KA-BLAMMO!!!!!

An enormous explosion rips through Gamma 3 – in fact, some overenthusiastic special-effects work initially suggests that it’s blown up altogether! – but when the [*cough*] smoke and flames clear, only about a quarter of the outer ring is badly damaged. (So the air-lock doors, which we were told couldn’t confine the creatures on their own, withstood this massive blast??)

The scanner into C Block shows that a few of the creatures have been killed—and that the rest are conspicuous by their absence. In fact they’re outside the station, basking in the sun and healing their injuries—and growing…

That’s enough for Rankin, who orders Gamma 3 (i) evacuated, and (ii) destroyed. Elliott argues that (i) it’s his station, and (ii) only General Thompson has the right to issue that order—and ends up being escorted off the premises for his pains.

Elliott finally cracks and takes a swing at Rankin—and this bastard screenplay won’t even let the punch land. Sigh.

—like you just don’t care!

Rankin gets back onto the line with Thompson, who has accepted that evacuation and the destruction of the station are necessary, but tells Rankin to concentrate on the former, as they on Earth can manage the latter remotely. “It’s your party,” replies Rankin ungraciously. Lisa and her unfortunate patients start getting ready to be loaded onto the first ship away, but then the escape-hatch doors won’t budge—because they’re covered in creatures.

Rankin orders Martin to take a party out to, “Blast ’em!” Elliott – sitting moodily in the evacuation area – decides to take over from Martin; although not before he’s had an embarrassing spat with Lisa. Oh, well.

What follows is a wonderfully terrible combination of obvious wire-work, third-rate bluescreen effects and monster suits, as Elliott and the others swoop around outside the station blasting creatures and trying to force them off the hatch.

The first evacuation ship gets away as a consequence of all this, but in the process one of the team is struck down by the creatures. Naturally Elliott goes immediately to the rescue, putting himself in danger as he shoots at the creatures and swoops in to carry the wounded man to safety. Watching in the monitor, Rankin shakes his head in reluctant admiration.

I may say that the only thing in this film more disgusting than Rankin’s general demeanour is the screenplay’s periodic attempts to convince us that it’s all a façade, that he’s a nice guy, really.

Finally everyone is evacuated but the senior officers and the security detail. Rankin orders everyone onto the last ship, but at the last moment Space Command must report that the station’s power has dropped so low, it cannot be remotely controlled from Earth—and that someone must therefore stay behind to set the station in motion, sending it plunging towards the Earth’s atmosphere and to its – and the creatures’ – destruction; assuming that person can fight his way to the controls in the first place…

’Tis but a scratch!

Rankin squares his jaw and accepts the task, sending everyone else away—though, suicide mission or not, it would make a lot more sense to assign a team; what happens if he fails? (Oh, yes, yes—I know…) Lisa now has a tacit, sad-eyed, oh-my-god-i-made-a-mistake moment, prompting Rankin to put on that nauseating smirk again before he sends her away.

The ship takes off, slowing to collect Elliott and his team (all of whom seem to have transmogrified into plastic dolls). On board, Elliott immediately notices Rankin’s absence. “He went back inside,” Lisa reports quietly. “Alone.”

And what do you suppose are the odds of him staying alone?

Oh, Vince, Vince, Vince…

You doofus.

Provided you can stomach its leading man, and the escalating bitch-fest between that leading man and his co-commander and erstwhile best friend, which occupies about 50% of the film’s dialogue, The Green Slime is a lot of fun—more than it would be, I think, if it were an objectively better film. And make no mistake, you could build a very good science-fiction film from the theoretical concept of this film’s monsters, which is very clever indeed. But the gap between theory and practice is very well illustrated here, in the charming if unconvincing life-cycle that carries those monsters from a goopy substance that surely must have inspired Mattel’s SLIME! to a waddling compendium of unnecessary appendages and peculiar vocalisations.

As it is, the most engaging thing about The Green Slime is the way that the film’s constant off-kilter feel – which manifests in everything from the monster design to the female crew-members’ leisure-wear to the film’s utter obliviousness to the qualities of character that put the “rank” in Rankin – leaves the viewer never quite sure what to expect next.

“Let’s see: I’ve lost my command…lost my girl…had my cojones handed to me… How could this day possibly get any worse?”

Except, of course, whenever Rankin and Elliott have a conversation.

Jack Rankin is so offensive that it’s hard to judge Robert Horton’s performance (though I stand by my earlier suggestion that some, at least, of Rankin’s abrasiveness was unintended), but Richard Jaeckel is right at home playing a nice guy in the process of finishing last. The only other performance worth mentioning is that of Robert Durham as Captain Martin, who projects a quiet competence even when Martin finds himself caught between his co-commanding officers like a kid whose parents are going through a messy divorce. Luciana Paluzzi, however, is a vacuous waste of space, even as her Lisa is just something for the men to squabble over—her medical degree be damned. Sadly, this bit of tokenism is entirely typical of science-fiction films of this era.

Now— I’ve given him a pretty hard time (to say the least), but maybe I can make up for just a bit of that by letting Jack Rankin, or at least Robert Horton, have the last word on The Green Slime:

“All over Manhattan, on the curbs all over Manhattan, were printed The Green Slime, The Green Slime, The Green Slime! I remember we went down to see it on 34th Street, and about three minutes before the film was going to be over with, I said, ‘Let’s get out of here; I have no desire to have anyone see me!’”

Call me crazy, but suddenly I have a mental image of Robert Horton and Jeff Morrow downing shots and crying on each other’s shoulders…

Speaking of slime…

You’ll find the full lyrics to the theme-song over in Immortal Dialogue.

Want a second opinion of The Green Slime? Visit 1000 Misspent Hours – And Counting.

♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦

This review is part of the B-Masters’ tribute to movie music!

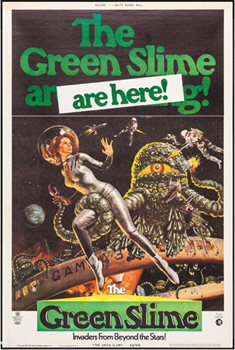

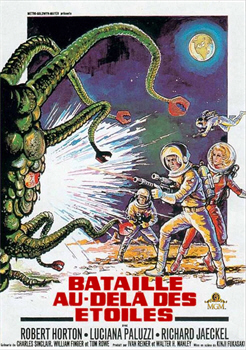

Now there’s a classic poster – clichéd imagery by the 1960s, sure, but it makes it clear what sort of film this is going to be.

There’s a Doctor Who story of the 1980s where people get around on some kind of small buggy – which not only moves at a slow walk, it’s driven by a noisy internal combustion engine. It may have been meant as parody; in late Doctor Who it can be hard to tell.

LikeLike

Though of course none of the women in the film get a chance to do anything requiring a space suit…

Those carts were pretty ubiquitous, and usually intended seriously, sadly enough.

LikeLike

Poor Luciana Paluzzi, she can’t catch a break – the main role I know her in is from Thunderball of course, where she’s shot by one of her own team of assassins.

LikeLike

I kind of understand the impulse…

LikeLike

Now speaking of Doctor Who:

A subject I’m a bit of an expert on. There is a green slime on the space station episode which may or may not have some elements stolen from this movie.

The Ark In Space. Tom Baker’s second serial. This ties nicely into the nostalgia of the Green Slime for me. It was my first viewing of a Doctor Who story on TV. Sort of.

In Central Pa., in the time before cable TV. When rabbit ears were the only chance to find something outside the local stations. There were three Philadelphia stations, 17, 29 and 43 on the UHF dial. Even at the best times the distance from the source signal made watching them a bit problematic. Grainy picture and sound was a norm. But, this kid would rush home to watch the likes of Kimba the White Lion. (Who’s the greatest animal in Africa? ), Marine Boy, and of course Ultraman. Doctor Who was also on, but at the time I discovered it the time slot was at a notoriously bad picture and sound quality. But I sort of got to see Jon Pertwee mucking about.

Finally, years later, the local PBS station made a big stink about purchasing the rights to show the Baker episodes of Dr. Who. We need ten more callers before we return to the Doctor’s adventures! And you get a tote bag. The thrill of finally seeing the Doctor without squiggly lines was good enough for the first story. But then the Ark In Space cemented my madness. (Cementia?) My introduction to the 1970’s Dr. Who special effects team. Which became a running joke with my family and friends over the years. Any low quality but endearing special effects were referred to as being a product of the Dr. Who special effects team.

From a later Who, “That sounded like a shot!”

No. It sounded like a board hitting a table.

For the Ark in Space, it was a rather unconvincing rubber balloon, perhaps suspended by string, against a backdrop of stars. Think Gamma Three on an even lower budget. The humans and the Dr. are trapped while a slimy green parasite with a slimy green slug trail clue to its presence infects one of the people. And here it changes from green ooze that was just a larvae into a Wirrn, an intergalactic insect.

So naturally when I first saw The Green Slime I said, “Dr. Who special effects team! COOL!”

These and many other Whovian coincidences have led to my unhealthy obsession with Jenna Coleman, including my purchase of the most tasteless custom made bumper sticker for my car. As Slime predates Ark this may be partially the fault of the former, and nothing to do with my own mental health issues.

LikeLike

My first full Dr. Who episode, I had seen the last episode of Robot, so I know the feeling. I was amazed at what the BBC crew could do with bubble wrap and green dye. LOL. Since I had only gotten bits of Robot, I still didn’t have any idea who this Doctor person was but I was hooked for life.

LikeLike

To be fair to the Doctor Who team, in 1975 bubble-wrap was not the commonplace thing it is today. But I’ll admit I’ve never worried about effects being photorealistic; as long as I can tell what they’re meant to be, that’s good enough for me.

LikeLike

And to be even more fair, there’s “low budget”, and then there’s “BBC low budget”. Ingenuity was all they had.

I’m generally pretty good at rolling with those sorts of things, but the relentless brightness of the lighting in The Green Slime – as if they wanted the plastic exposed – is a bit confronting. Like suddenly discovering that someone is a practising nudist.

LikeLike

Shouldn’t it be “The Green Slime IS Coming”? Or “The Green Slimes ARE Coming”?

and once again, the lesson to men that the more obnoxious you are, the more irresistible women will find you. Sigh.

LikeLike

Well, I believe Japanese doesn’t make a grammatical distinction between singular and plural…

LikeLike

You could further complicate it with the question are the Green Slime truly separate creatures are some sort of hive/colony organism.

LikeLike

An argument that has been raging since 1968!

Alpha male types make my skin crawl, so granted, I’m not the best judge; but even in that context I would have to say that Rankin is something special.

LikeLike

What a great week, you are doing two of my favorites from my childhood. This movie in particular. I first encountered it on a late night sci-fi movie showing after my bedtime, so I had to sneak into the living room after my parents went to bed to watch it in the dark. hehe. Of course, this one didn’t give me the nightmare fuel that The Blob did, you are right the aliens were just the right balance of coolness and cheesy to make the movie very enjoyable but not really scary.

(Sorry if this posts more than once, WordPress and I are having difficulties.)

LikeLike

(That’s okay, I took care of the multiples.)

I’m glad; mine too, obviously! The first time I saw The Green Slime was that cinema screening, and it was an epoch-making event, I can tell you. 😀

LikeLike

This movie was the topic of the first issue of Famous Monsters of Filmland I bought. I had to wait two decades to see it. The theme song hooked me, then the glorious cheese level reeled me in. I seem to remember a pocket sized game that centered on the plot of this for the game play.

LikeLike

The Awful Green Things From Outer Space? First published in 1979, and still available in recent editions – one player takes the crew of an exploration ship, the other the aliens. The aliens grow or breed every turn; the crew have various things to fight them with, but the effects are randomised at the start of the game, so maybe setting off the drum of rocket fuel will destroy them, or maybe it’ll make them grow.

LikeLike

That is absolutely the game I was thinking of. In addition to my Sci -FI horror movie obsession I also played Dungeons and Dragons. Since that first appeared in Dragon magazine I was aware of what its origins were.

There’s also a game that played out similarly based on Sigourney Weaver style Aliens.

LikeLike

I remember that one and another pocket game that was even simpler and it was a pocket game, one of those distributed in little ziplock baggies. It had a space station layout map and counters. It was more based on Aliens with one player trying to defeat them and if there were two players the other playing the monsters. If solo, the monster, and escaped lab animal counters were turned over and randomly moved around the map.

LikeLike

So, I’m curious: How’d you manage to snatch the two movies with possibly the best theme songs ever? I suppose being able to do the “one rewritten, one new” thing you like to do helped. (I wanted to make a joke about you having your choice because no one else is reviewing anything this time, but it just made me sad.)

I first saw this in high school, and really hadn’t seen anything like it before. Fell in love with the song immediately, of course, and the monsters (who are indeed as adorable as all get out, though their vocalizations grate on me after a while). Thanks to my love of giant monsters I was able to deal with the patently phony models, but those scenes with the little blobs stuck on the space station model…hoo boy.

From the context I’m guessing “chammies” would be slang for glasses of champagne? I could not find a definition remotely like that when I Googled it. Is it national, regional, local, or household?

And he’ll always be Jack “I’M A SMUG BASTARD!” Rankin to me.

LikeLike

I actually had a lot of trouble with this one inasmuch as all the films I thought of as appropriate, I’d already tackled. Of course that was true of The Green Slime too, but pairing it with The Blob seemed like a good excuse…though still rather a soft option, while the others were mostly talking in terms of full film scores. (On the other hand, *I’ve* posted, so there’s that…)

Oh, I can deal with them…though I do appreciate a little effort to tart things up!

National, but possibly confined to the female of the species—i.e. an appropriate way to offer a glass of champagne would be, “Chammie, love?”

Well, he’ll certainly always be a smug bastard… 👿

LikeLike

You finally did it, you wonderful mad scientist, you “re-reviewed” The Green Slime! I don’t need anything else for Christmas this year!

So, is Rankin the most egregiously unlikable protagonist on film? The leads in Rent give him serious competition but then there are several of them whereas he manages to thoroughly repulse me all on his own…

LikeLike

Nic Cage’s character in Wings of the Apache / Fire Birds is pretty vile.

LikeLike

Elvis in Jailhouse Rock? Richard Chance in To Live and Die in LA? The whole cast of Cannibal Holocaust?

LikeLike

It’s been a long, long time since I’ve seen Jailhouse Rock and To live and Die in L.A. so I can’t remember much about them. I’ve never seen Cannibal Holocaust – and likely never will. I have great difficulty watching films with fake animal violence let alone the real thing. Rankin scores really high because not only is he a complete ass but because the film overtly portrays him as a man much to be admired. Tom Cruise in Top Gun comes close I suppose. (I also harbor extra resentment against that film because Art Scholl was killed doing aerial filming for it)

LikeLike

I was glad to find an excuse to revisit it, Ray. 🙂

There’s no shortage of unlikeable protagonists around, although usually there’s a question, at least, of how the viewer is intended to take them. Rankin, like many of the 80s action heroes, offends for apparently having the unqualified support of the film that contains him. Good call on Tom Cruise in that respect (who I always found creepy-repellent, irrespective of the film).

LikeLiked by 1 person

Spirits you’ll have to bring up Top Gun and those homo-erotic lockerroom vibes. *laughs* My wife and I are both slash/shipper fiction fans so that now pops into my head the idea that maybe all that competition and tension between Rankin and Elliot might have been a symptom of something else? *evil grin*

LikeLike

At least that would make more sense than them fighting over Lisa “Waste Of Space” Benson.

(Actually…Lisa as their mutual beard makes perfect sense…)

LikeLike

Kudos for being much too class an act to resort to “C-Block” jokes…

😉

LikeLike

Ehhh, I’m the wrong generation for that. 🙂

LikeLike

“You’re not fit for command. You make too many bad decisions. You’re short, you’re ugly, and you’re lousy in bed.”

…well that SEEMS like what he wanted to say.

LikeLike

I swear the theme song singer sounds like Arthur Brown (of Crazy World of Arthur Brown). I can see him singing this live with his famous flaming head piece.

LikeLiked by 1 person