“The destiny of the priests of Karnak is fulfilled! Not one of you who tried to enter the tomb of Ananka will leave this valley alive…”

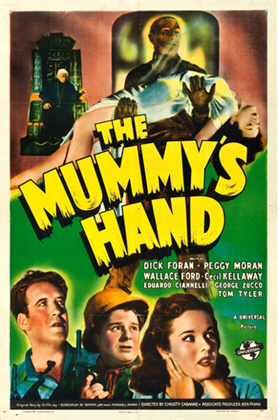

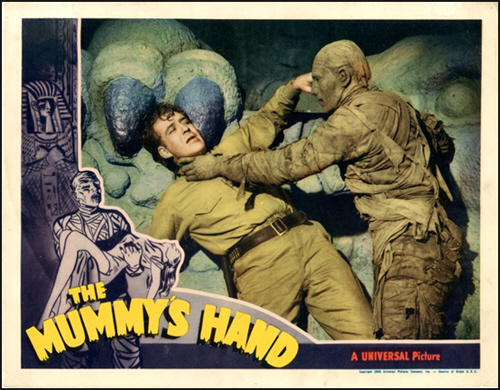

Director: Christy Cabanne

Starring: Dick Foran, George Zucco, Wallace Ford, Peggy Moran, Cecil Kellaway, Charles Trowbridge, Eduardo Ciannelli, Siegfried Arno, Tom Tyler, Michael Mark

Screenplay: Griffin Jay and Maxwell Shane, based upon a story by Griffin Jay

Synopsis: The High Priest of the Temple of Karnak (Eduardo Ciannelli), knowing that he is dying, summons his successor, explaining to him the great secret that it will be his duty to guard. Via a vision in a magic pool, the High Priest tells the younger man a story of three thousand years before: the death of the Princess Ananka, daughter of King Amenophis, and the bitter grief of her lover, Kharis (Tom Tyler), a prince of the royal house; a grief that drove him to an act of sacrilege. Breaking into the altar room of Isis, Kharis stole a supply of tana leaves, from which a potion might be brewed that would bring Ananka back to life. However, he was caught in the act, condemned, and buried alive, his bandage-wrapped body placed in a cave on the far side of the mountain in which Ananka’s tomb was built. There, the High Priest concludes, Kharis has been ever since, caught between life and death. The High Priest goes on to explain the use of the tana leaves, now rare and precious after the plant that bore them became extinct: how to keep Kharis in a state of suspended animation, or raise him to new life—or turn him into a killer. Having received an oath of faithful duty from his successor, the High Priest dies… In a Cairo market, archaeologist Steve Banning (Dick Foran) examines intently a broken vase, insisting upon buying it even though it takes almost all of the money needed to carry Steve and his friend, Babe Jenson (Wallace Ford), back to America. Nearby, unbeknownst to the Americans, a beggar (Siegfried Arno) listens intently… Steve takes the vase to Dr Petrie (Charles Trowbridge) at the Cairo Museum, who agrees with him that it is authentic, and a valuable clue to the still-hidden tomb of the Princess Ananka. Excitedly, Petrie takes Steve and his find to consult Professor Andoheb (George Zucco), the museum’s resident expert—and also the new High Priest of Karnak. To the dismay of Steve and Petrie, Andoheb contemptuously dismisses the vase as a fake. Steve, unconvinced, announces his intention of mounting an expedition anyway. He asks for the vase back, but it slips through Andoheb’s fingers and shatters. Later, Petrie reaffirms his own belief in the authenticity of the vase, while Steve swears that he will raise the money needed somehow. In a bar, Steve and Babe fall in with a stage magician, Solvani the Great (Cecil Kellaway), a fellow Booklynite who is persuaded to enter into partnership with them. This is overheard by the beggar from the marketplace, a follower of Karnak, who Andoheb has ordered to follow Steve. Shortly afterwards, Marta Solvani (Peggy Foran) receives a visit from Andoheb, who warns her that her father has fallen in with a pair of known swindlers, possibly murderers, who make their fortune by convincing people to invest in fake expeditions. When a highly intoxicated Solvani staggers in some hours later, Marta learns to her horror that he has handed to Steve the money meant for their boat tickets. Furious, Marta arms herself with a trick pistol and goes to the Cairo Hotel, demanding the money back. Steve manages to disarm her, and insists upon the legitimacy of the business deal. Learning that the money has already been spent, Marta announces her intention of joining the expedition. The party sets out across the desert, locating the Hill of the Seven Jackals. Its first find is a gruesome one: the skeletal remains of the members of a previous expedition; but the explorers then discover a hidden tomb, marked with the Seal of the Seven Jackals. The natives attached to the expedition recoil, as their head man warns that to break that seal means certain death. The archaeologists press on regardless. Inside they find, not the tomb of the Princess Ananka, but a sarcophagus containing a mummy: the mummy of a man who was buried alive…

Comments: Much as some of us might bemoan the constant stream of sequels, prequels, and re-makes that emanates from Hollywood today, it is certainly not a new phenomenon. As film technique improved throughout the silent era, endless motion pictures were shot and re-shot to reflect the fact; while the move from silent film to talking pictures was another cue for countless films to get a makeover. Even the shift from the anything-goes attitude of the pre-Production Code era to the rule-bound post-Code world was an excuse for certain productions to be re-made in more “acceptable” form.

It was, however, those behind the making of Hollywood’s first and greatest wave of horror movies who first grasped the concept not merely of the re-make, but the franchise—and embraced it. Film series were common enough, of course, but it was Carl Laemmle and his people at Universal Studios who realised that the supernatural themes of their lucrative new specialty offered the perfect pretext for returning to the well as often as they liked. Sure the monster was killed off at the end of each film…but just because it was dead, that didn’t mean it had to stay dead, right?

Although the motivation behind their repeated resurrection was certainly predominantly financial, for the most part the classic Universal monsters were treated with respect by their studio; and if there was a decline in the quality of the films over time, it had more to do with external social and economic factors than with the attitude of the film-makers.

Frankenstein was the most profitable of the Universal horrors, and consequently its sequels received the highest budgets and greatest attention: Bride Of Frankenstein, Son Of Frankenstein and even The Ghost Of Frankenstein are all worthy successors. Dracula fared less well, but still spawned the odd but interesting Dracula’s Daughter, while Son Of Dracula is an underrated gem. The Invisible Man Returns took the interesting step of having a concept, rather than a character, as its recurrent aspect—and gave Vincent Price an important early genre role. The Wolf Man alone, coming late to the party, was not granted the dignity of a solo starring role in his sequel, but found himself immediately tossed into the first of the Universal “monster rumbles”, Frankenstein Meets The Wolf Man.

It was The Mummy, however, that leapt rather than slid into the realm of the franchise.

By 1940, much of the world was at war, and the edict against horror movies instigated in the late thirties merely on grounds of social disapproval had strengthened into one based on the understandable feeling that there were quite enough real horrors abroad without the need for any added fictional ones, thank you very much.

Meanwhile, after teetering on the brink of disaster for the best part of a decade, the Laemmles had finally lost control of Universal Studios in 1936, with James Whale’s version of Show Boat ultimately responsible for his employers’ demise. The only way that the Laemmles had been able to begin work on Show Boat in the first place was to take out a huge loan using the studio itself as collateral. When the production went over-schedule and over-budget, the Laemmles were unable to meet their repayments, and were forced to surrender control of Universal to a business conglomerate. Ironically, Show Boat¸ when it was finally released, was a smash hit and a huge financial success.

(Which, as it turned out, did James Whale himself as much good as it did the Laemmles. The new owners of Universal did not approve of Whale, either personally or artistically, one little bit, and subsequently devoted considerable effort to driving him out of the studio, effectively ending his career.)

John Cheever Cowdin, a prominent financier and sportsman, was appointed chairman of Universal at this time and immediately set about retrenching, severing the studio’s ties with its contracted stars and, apart from approving a handful of carefully-considered, rigidly-budgeted, higher-quality productions, spending the rest of the decade turning Universal into a factory for cost-effective genre films: musicals, westerns, melodramas—and horror movies.

Horror movies, yes; but not horror movies as the world had known them until then. Gone were the serious, often disturbing, carefully-crafted works that had kept Universal in business throughout the 1930s. In their place were B-movies – literal B-movies: short, inexpensive films destined for the bottom half of a double-bill, and intended not to frighten or provoke, but merely to entertain by providing a few mild thrills.

Amongst them were four films featuring the only one of Universal’s classic monsters who had not, by the end of the thirties, already been revived for the purposes of a sequel: the mummy. Fascinatingly, these films set about completely revising the mythology and the motives as presented in the 1932 production, operating not as true sequels to The Mummy, but as what today we would certainly call a “re-boot”.

The Mummy’s Hand wastes no time in letting the audience know exactly what has changed, either: it devotes its opening ten minutes – out of a total running-time of only sixty-seven – to re-working the story of The Mummy into more usable terms. The scale on which the production is operating is also immediately evident. As would its three succeeding series entries, The Mummy’s Hand saves costs by using and re-using long stretches of footage from The Mummy, invariably including the flashback sequence wherein Ardath Bey, the resurrected form of the eons-dead High Priest Imhotep, shows Helen Grosvenor, the reincarnation of the Princess Anck-es-en-Amon, the history of their lives and deaths.

This footage actually includes shots of Boris Karloff, although it is not obvious unless you are really looking for him; while for the close-ups, and to alter as needed various aspects of the story, newly-shot scenes featuring Tom Tyler are interwoven with the recycled material. Tyler was, of course, best known at this time as a star of westerns. He was cast in this, his only horror film, because of his height and angularity of build, which were felt to make him a reasonable visual substitute for Karloff. The integration of the new and old footage here is quite well done.

(Admittedly though, if you do happen to be in a disrespectful mood, this section of the film lends itself exceedingly well to a game of Boris / Not-Boris.)

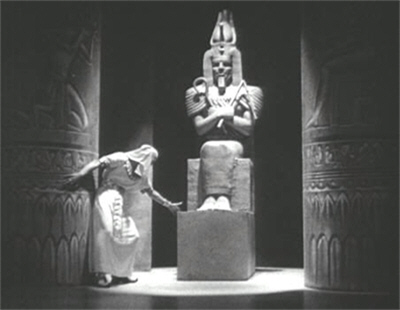

The opening of The Mummy’s Hand sees the dying High Priest of Karnak – which, amusingly, the screenwriters seem to think is an Egyptian god rather than a place – explaining his responsibilities to his nominated successor. As this series of films went on, its primary pleasure (apart from its wild leaps in geography and chronology) would turn out to be the various High Priests who would act as their main antagonists. Thing get off to a fine start here, with a heavily made-up Eduardo Ciannelli handing over the medallion of the High Priests to a more than usually unctuous George Zucco, who goes through the film looking very dapper in a stylish suit-and-fez combination.

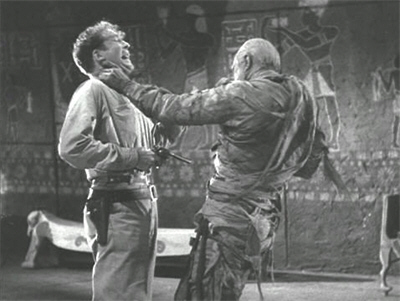

xxBoris…………………………………………………………..Not Boris

The High Priest takes the younger man to the magic pool, now held to contain the Waters of Kar, and summons up for him our re-tooled back story. Here, the dead Princess Ananka is mourned by her lover, who has been re-named Kharis and promoted to “prince of the royal house”. His subsequent desecration of the altar of Isis is committed in order to steal, not the Scroll of Thoth, but a casket of tana leaves, which have the power to resurrect the dead. Kharis is caught in the act and condemned to have his tongue cut out, and then to be swathed in bandages and buried alive. Kharis’s sarcophagus is subsequently placed in a cave within the same mountain that contains the hidden tomb of the Princess Ananka…

Kharis, the High Priest goes on to reveal, is not actually dead, but in a state of suspended animation. A brew derived from three tana leaves, administered to the inanimate figure on nights when the moon is full, keeps him so; but should the temple of Ananka be threatened, it is within the power of the High Priest to bring Kharis to life using nine tana leaves, so that he might kill those responsible. No more than nine leaves should ever be brewed, however, the High Priest concludes, for then Kharis would become unstoppable…

Then, having kindly spelled out for us the rules of the game, the High Priest hands over his medallion, and dies.

And now, what will happen in the event of Ananka’s tomb being desecrated having been explained to us, it’s naturally time to meet the people who will desecrate it – and for The Mummy’s Hand to take a painful turn. The opening credits to this film contain three dead give-aways as to its nature, in the names of director Christy Cabanne and screenwriters Griffin Jay and Maxwell Shane. Cabanne was a former writer and stage director who had graduated to silent film acting and from there to directing; over time he would become one of the most prolific directors in the history of Hollywood. Jay, meanwhile, had learned his trade writing serials; while Shane, although he would go on to produce the Boris Karloff TV series Thriller, had his greatest success writing radio comedies.

What the three men had most in common, however, was not their vision or originality, but their ability to work quickly, efficiently and inexpensively. They were, in short, exactly what the new owners of Universal Studios were looking for in 1940. (This period actually represented a high point for Cabanne and Jay: the former would end up at Monogram, and the latter at PRC.) It is, therefore, not surprising that both the characterisations and the action of The Mummy’s Hand are rendered in broad strokes—and nor is it that we should find amongst the supporting cast an Odious Comic Relief in the form of Babe Jenson, played by Wallace Ford.

Impossible as it is not to wince and sigh these days over Babe’s unfunny antics, it is necessary to keep in mind the prevailing social conditions of the time of this film’s production, and the sense that anything that might actually be horrific in a horror film must immediately be undermined. The irony here, at least to my mind, is that this imposed juxtapositioning of horror and (alleged) comedy really makes things worse, not better: it trivialises the violence in a way that looks forward to the action films of the 1980s and beyond, where gruesome death was invariably greeted with a smartarse remark. Here, for instance, we have the killing of Dr Petrie by Kharis, and the discovery of his body, sitting cheek by jowl with a scene in which some of the other characters chuckle merrily over Babe’s inability to master a childish magic trick.

While we might understand the motives at work here – as least to the extent that the inclusion of an Odious Comic Relief is ever understandable – The Mummy’s Hand would certainly have been better served by a Babe who was simply your standard, two-fisted, unshakably loyal hero’s sidekick. This approach would also have rendered the film’s climax, which as it stands features the Odious Comic Relief suddenly unleashing some very straight violence, and displaying a degree of competency that we have no reason to expect, a lot less jarring.

Be that as it may, our very first glimpse of our protagonists is enough to tell us how things actually are, with out-of-pocket archaeologist Steve Banning examining artefacts in a Cairo market while his friend Babe Jenson amuses himself by needlessly insulting a beggar, and then dancing a duet with a gyrating wind-up doll dubbed “Poopsie”.

Steve ends up spending most of the money the two have stashed away to carry them home – to Brooklyn, naturally – on a broken vase, which bears inscriptions that have roused all of his professional instincts.

(The seller of the vase is played by Michael Mark, whose genre credits stretch from Frankenstein to The Wasp Woman.)

Steve carries his find to Dr Petrie of the Cairo Museum, who is equally excited, believing as Steve does that the inscriptions may be a clue to the whereabouts of the almost legendary tomb of the Princess Ananka, in pursuit of which many lives have been lost over the years. However, Petrie suggests that they get confirmation from the museum’s Professor Andoheb, a leading expert in such matters. What seems like admirable caution soon strikes the viewer as anything but, however, when Steve is introduced to the good professor…a man we already know as the new High Priest of Karnak.

Dum, dum, dumm.

Andoheb, of course, recognises at a glance the significance of the vase, and instantly sets about demoralising Steve with a well-judged mixture of condescension and sarcasm. Steve is nevertheless confident enough – and pig-headed enough – to back his own judgement anyway, rather unadvisedly making that clear to Andoheb before demanding the vase back. We are hardly surprised when it, ahem, slips through the professor’s fingers. This only confirms Steve in his determination to pursue the matter, however, and his doggedness has the effect of restoring Petrie’s own belief in the vase’s authenticity, which was briefly shaken by Andoheb’s sniffy dismissal of it. The two men agree to mount an expedition—just as soon as Steve can afford to pay for it.

The subsequent pursuit of money introduces our final two main (living) characters: Solvani the Great – aka Tim Sullivan – and his daughter, Marta; stage magician and assistant, respectively.

(For all Babe’s efforts, nothing in The Mummy’s Hand amuses me quite so much as its attempt to sell the South African born, Australian bred Cecil Kellaway as a Brooklynite, albeit one of Irish extraction.)

An unnecessarily protracted “comic” scene has Babe trying to take Solvani for a drink, and being thoroughly taken himself. Steve, Babe and Solvani then sit down for a boozing session, in the course of which Steve manages to persuade Solvani to fund his expedition, in return for a third of the profits.

This film is almost touching in its belief that archaeologists simply get to keep whatever they find.

The negotiations are overheard by the beggar from the marketplace, who turns out to be a follower of Karnak. (So I guess it’s okay that Babe was rude to him, huh?) He instigates a brawl, presumably in the hope of landing one or all of the Americans in trouble with the local police. This failing, the beggar reports to Andoheb, with the result that Marta Solvani, or Sullivan, is interrupted in the midst of packing for her father and herself by a visit from the professor himself. Andoheb warns her that there are dangerous con-artists operating in Cairo, who convince strangers to back phony expeditions and then, after pocketing their money, lead them into the desert and murder them.

Marta is suitably horrified, and promises to guard her father against any such attacks. She is too late, however: Solvani comes staggering and hiccoughing in some time later, and confesses to handing over all their money to someone whose name he can’t quite remember, and whose address he doesn’t seem to have… However, Solvani does have a hand-written contract, scribbled on stationery from the Cairo Hotel. This is enough for Marta, who arms herself with a trick pistol from her father’s magic act and storms off, bailing up Babe in mistake for Steve before being disarmed by Steve himself, and thus providing the obligatory Cute Meet. Learning that Steve has already spent all of Solvani’s money, Marta announces that she will be joining the expedition, to look after her father and their investment.

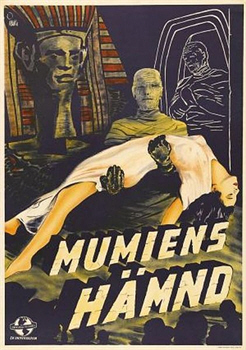

In truth, Marta’s presence in this film is almost as unnecessary as Babe’s clowning; the screenwriters have a devil of a time trying to come up with anything for her to do – beyond being rude in the guise of being feisty – right up to the point when she is carried off by the reanimated Kharis, and thus provides a welcome bit of visual iconography.

Finally – and at better than halfway through the film – the action of The Mummy’s Hand shifts out into the desert. The expedition’s first find is of a distinctly gruesome nature: the skeletal remains of married archaeologists who disappeared two years earlier. Shortly afterwards, the dynamiting of a cliff-face (by Babe: can you actually imagine anyone putting this idiot in charge of the explosives!?) reveals the entrance to a hidden tomb, and a seal: the Seal of the Seven Jackals.

This is enough to provoke a cry of dismay from Ali, the leader of the native diggers, who immediately designates the tomb as “unholy”, and warns of the curse that dooms anyone who breaks the seal. This elicits the usual hand-waving and scoffing and muttering about “superstitious natives” from the all-knowing white people, who unhesitatingly force their way into the tomb.

(To the writers’ credit, we note that it is in fact Dr Petrie who actually breaks the seal.)

However, far from finding themselves in the glories of Ananka’s tomb, the bemused archaeologists end up inside a fairly barren cave containing a single, undecorated sarcophagus – which isn’t sealed – and which in turn contains a bandage-swathed figure that is unmistakably that of a man. Although Petrie is excited by the state of the mummy, which is remarkably preserved, the others can’t see past the absence of treasure. Sitting later around a campfire, Solvani and Marta bitch about the state of affairs; and we get the single moment in the film when Babe comes across as likeable, as he fires up in defence of Steve. Of course, he brings hatred down upon himself again literally a second later, by “comically” confusing a jackal with a jackass; oh, well.

Meanwhile, Steve and Petrie are examining the mummy, determining that it is that of a man called Kharis, who was buried alive, and that it is so well-preserved as for it to feel to the touch like living tissue. Petrie also points out a huge urn, filled with what he identifies as tana leaves, guessing that they were used somehow in the embalming process.

(In a sad piece of likelihood, the tree from which the leaves were derived is declared to be extinct…which, it must be said, has no effect at all upon the seemingly inexhaustible supply of tana leaves that appear here and in this film’s three sequels. I might add that, at least to this reviewer’s jaded eyes, the tana leaves bear a distinct resemblance to eucalyptus leaves.)

Interesting as all this is, Steve is fixated upon the puzzling lack of any reference within the cave to Ananka. He is called away by Babe, and confronted by the news that his diggers, who took to their heels upon the tomb being opened, won’t be coming back.

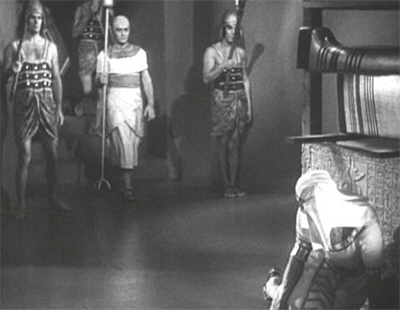

Inside, Petrie is replacing the tana leaves when a smooth voice speaks from the shadows. It is Andoheb, of course, who in fact has been lurking in the area for some time, and witnessed the breaking of the seal. Petrie is bewildered by the professor’s presence, and considerably more than bewildered when the sardonically smiling Andoheb begins an odd demonstration. First, he has Petrie feel for Kharis’s pulse—which he finds. Secondly, Andoheb pours a fluid that he describes as having been brewed from nine tana leaves between the mummy’s shrivelled lips. Kharis’s pulse rate increases…and then he stirs. His hand closes about Petrie’s wrist, and his eyelids lift—revealing the black, glittering pools beyond. Overwhelmed with terror, Petrie struggles unavailingly to free himself from the grip of the mummy, which takes his throat in one hand…

Out at the campsite, Steve and Babe hear Petrie’s despairing cries, but by the time they make it back into the cave, Andoheb has disappeared—and so has Kharis. Petrie is dead, clearly having been strangled, the only clue to his killer the strange grey residue left upon his neck…

Around the other side of the mountain, in Ananka’s tomb, Andoheb orders the beggar to place vials of tana fluid within the tents of those others who have been marked for death, since Kharis, in pursuit of the precious substance, will kill anyone who gets between him and it.

Meanwhile, Marta is making her one major contribution to the proceedings, pointing out an interpretation of the figures from the vase that Steve had not considered, and suggesting that the cave is perhaps in front of – even connected to – Ananka’s tomb. (Although how Steve himself failed to think of that…) Steve, Marta, Babe and Solvani immediately begin hunting for the theoretical hidden passageway, leaving the disposable Ali alone at the campsite. Sure enough, Kharis comes shuffling along…

Back in the cave, while the menfolk are agreeing to pack it in and get a fresh start in the morning, Marta notices that the tana leaves have all gone from the urn. With no explanation to hand, the four return to camp. Ali’s apparent disappearance is noted, and his body discovered in the Solvanis’ tent hard on the heels of Babe’s sneering observation about how, “You can’t trust these gypsies.” No apology is forthcoming, however.

Steve announces that enough is enough, and that they will all be leaving in the morning. He gives up his and Babe’s tent to Marta and her father, while he and Babe strap on handguns and mount guard. Just the same, the beggar manages to slip another vial of tana fluid under the tent-flap and place it near Solvani’s bed, so that he becomes the next target.

You know, I can only assume that somewhere in the by-laws of Karnak worship there is an embargo against dirtying your hands, because it really would be quicker and simpler if Andoheb and/or the beggar just killed everyone themselves. I also assume that this was the point at which Griffin Jay and Maxwell Shane realised they had written themselves into a bit of a corner, inasmuch as they only had headlining stars (of a sort) left at their disposal. So it is that Kharis’s assault upon the Solvanis’ tent ends with Solvani himself surviving the mummy’s attack, and Marta – who has fainted, of course – being carried off.

Steve and Babe catch a glimpse of the receding forms of Kharis and Marta, but by the time they have run into the cave the other two have disappeared.

The search for the hidden passageway is then resumed with extreme urgency, but yields nothing but the discovery that the now-empty urn has been smashed. Upon re-emerging from the cave, Steve and Babe surprise and shoot dead the beggar, whose medallion bears clearly the image that was only present incomplete on Steve’s broken vase, and confirms the existence of a secret passage. It also suggests a second, external entrance to Ananka’s tomb. Steve returns to the search for the former, while sending Babe off to hunt for the latter.

Kharis carries Marta, still in a faint, into Ananka’s tomb, where she is placed upon the sacrificial altar and bound. When she finally comes to, her abduction is revealed to have been instigated by Andoheb, the result of a fixation upon the girl of which the single meeting we observed between them gave not the slightest hint; while there was certainly no, “But don’t kill the girl!” injunction in Andoheb’s instructions to Kharis, either. Andoheb announces his intention of bestowing immortality upon both himself and the girl, but since this plan comes with the proviso that Marta will subsequently spend eternity in the tomb with him as his “High Priestess”, it is perhaps not surprising that her response is a vociferous protest.

Back in the cave, Steve discovers that the smashed urn, once reassembled, carries an explanation for the use of the tana leaves, and directions to the hidden passageway—which is, duh, behind the mummy case.

The Mummy’s Hand then rushes to its conclusion, giving us attempted immortality, gun-play and mummy-wrestling in very rapid succession. Thankfully, this section of the film is played completely straight. Steve repeatedly imposes himself between Kharis and the bowl of concentrated tana fluid intended by Andoheb to bring about his own immortality, and takes quite a beating as a consequence; while at this last extremity, Babe actually makes himself useful; twice.

(In a wonderful touch, Steve at one point tries to stop Kharis from getting the tana fluid by shoulder-charging him: a cloud of dust explodes from the mummy’s bandages.)

In the course of the struggle, the tana fluid is spilled, leading to the unexpectedly upsetting sight of Kharis face down upon the floor, lapping at the liquid like a junkie unable to control his cravings. It is a posture that leaves him terribly vulnerable to attack…

As a film in its own right, The Mummy’s Hand is a brisk and fairly efficient effort, mixing occasional welcome flashes of imagination with equally enjoyable absurdities. Not least among these is the fact that Ananka’s long-lost tomb is, apparently, not only an easy camel-ride from Cairo, but clearly visible from the road! The tomb itself is a wonderful piece of eye-candy, but it comes as little surprise to learn that, like the footage from The Mummy, it was recycled from another production, in this case the James Whale-directed Green Hell. This temple set would continue to put in appearances in Universal adventure films right throughout the 1940s, including Cobra Woman—and never mind that it was supposed in the first place to be Incan.

On the positive side, the screenplay of The Mummy’s Hand contains scattered reminders of earlier Universal horror films, with various cries of, “It’s alive!”, and a reference by the old High Priest, in response to the howling of a jackal, to, “Children of the night!” George Zucco is a lot of oily fun as Andoheb (and comes to a most ignominious end), while Dick Foran is solid and credible as Steve, who we can admire both for his determination to mount his expedition in the face of Andoheb’s jeers, and for his willingness to abandon it for the sake of his companions once things go wrong, whatever the cost to his own feelings and ambitions. You do have to wonder why he puts up with Babe, though, in whose defence there is not much that can be said.

(Not as a character, anyway; but perhaps as evidence of a screenwriters’ game of “outwit the censor”. There is a certain underlying ambiguity about Babe’s relationship with Steve, to which his nickname is a clear pointer. At the beginning of the film, at the market, when Steve calls out, “Hey, Babe!”, it is a female vendor who instinctively answers him; Babe has to explain that, no, Steve means him. And later, when Marta all-but-confesses to Babe that she loves Steve, Babe all-but-confesses to her that he does, too.)

But much as we complain about Babe, it is hard to dispute the fact that much of The Great Solvani’s schtick is just as tiresome as Babe’s, or would be if it were not for Cecil Kellaway’s natural charm. Peggy Moran is little more than a prop here, although you certainly can’t complain that the romance between Steve and Marta slows the action down, consisting as it does of a single fleeting kiss and a declaration by the latter that Steve is, “Pretty swell.” In fact, the most interesting thing about Marta isn’t actually about Marta at all. Rather, it is the total absence of any suggestion that Marta is the reincarnation of the Princess Ananka.

That aspect of The Mummy would, however, eventually turn up in the sequels to this film. Its removal here contributes to the overall “downgrading” of Kharis himself, who is neither the focus of the film, as was Imhotep, nor the romantically-driven figure of various later mummy movies, but rather—just a monster.

However, thanks to Jack Pierce’s handiwork, Tom Tyler is an effective and scary presence in his one turn under the bandages, while the post-production blacking out of Kharis’s eyes is a simple yet wonderfully creepy effect that does indeed lend a sense of supernatural malevolence to the shambling figure. At the same time, the mummy’s physical deficiencies, intended as indications of the incomplete nature of his revival under the effects of nine tana leaves only, have the inevitable effect of handicapping his murderous activities, so that the script must keep finding ways for his intended victims to be cornered—thus avoiding the unwelcome sight of Kharis being easily outrun by his prey.

While there is little disputing that The Mummy is far finer work than The Mummy’s Hand and its sequels, the fact remains that many people prefer these little B-movies to their predecessor on the grounds that this is the way that mummy movies should be. Now conditioned to expect a shambling, bandaged figure to be front and centre, viewers new to the earlier film often come away from it puzzled and even disappointed, wondering where the mummy was? – a piece of retroactive judgement that does The Mummy a grave injustice.

The decision of the makers of The Mummy’s Hand to take the single figure of Imhotep / Ardath Bey and divide it into two, the High Priest and the mummy in his service, was a critical one, particularly with the simultaneous invention of the tana leaves. The resulting mythos, with its central concept of a bandaged, ambulatory, murderously-inclined mummy, took hold in the imagination of the movie-going public; so much so that the fact that the mummy itself was reduced from being the real star of the show to being nothing more than a mute, lumbering sidekick, a tool in the hands of the High Priest, either wasn’t noticed or was considered not to matter.

Similarly, Kharis’s pose here, one hand clutched to his body and one outstretched, one foot dragging behind, became the “correct” stance for a mummy—just as the outstretched arms in Frankenstein Meets The Wolf Man would in time become accepted as the “right” way to depict Frankenstein’s creation, even though they were in fact no more than the legacy of ill-considered re-writes.

I could rave for page after page about the artistic superiority of The Mummy (and, of course, did), but my doing so would not alter the fact that in spite of its manifest shortcomings, The Mummy’s Hand is in every respect the more influential film. If a comparison of these two productions proves anything, it is that there truly is no accounting for taste – or any way to anticipate what random details will lodge themselves in the crevices of popular culture, take root there, and flourish.

Want a second opinion of The Mummy’s Hand? Visit 1000 Misspent Hours – And Counting.

“In the course of the struggle, the tana fluid is spilled, leading to the unexpectedly upsetting sight of Kharis face down upon the floor, lapping at the liquid like a junkie unable to control his cravings.”

Lapping? With his tongue? That was supposedly cut out?

Not that slurping at the floor with his lips would be any more dignified ….

LikeLike

Alas, yes: slurping it actually is, poor Kharis!

LikeLike

I was sort of cringing at the mention of using dynamite to find the hidden tomb. Ah, the simplicity of movie archeology.

LikeLike

Accidentally-triggered dynamite…

LikeLike

In this movie and all its sequels, it’s amazing how easily the High Priest or his servant succumbs to temptation. One of them is always falling for the girl and is all set to betraying his sacred vows.

LikeLike

I guess American girls are just that irresistible. 😀

LikeLike

This whole mess was started by a Karnakian priest who couldn’t keep it in his robes, I wonder if it’s ironic that the attempts of future priests to punish those who violate the princess’ tomb are likewise thwarted by priests who couldn’t keep it in their robes? There’s clearly a pattern there, is what I’m saying.

LikeLike

“But boss, when we sneak into the tents of our intended victims, why don’t we just cut their throats?” “Because that is not the Karnaki Way.”

Yeah, very interesting to see how the “modern girl as reincarnation/double of the princess” angle has been dropped completely. I wonder why – not enough time? Thought to be not interesting enough? Not really compatible with the mummy as an automaton?

LikeLike

I think a combination of both those answers; although in typical franchise style the next two films will refute the implications of the first two…

LikeLike

I remember reading somewhere that Tom Tyler was arthritic by the time they shot this movie, and that is the reason for his shuffling gait and stiff gestures. Is this true?

LikeLike

I believe it was several years after this when Tyler’s arthritis brought his career to an effective end. It may already have been hampering him when he made The Mummy’s Hand, but then he played Captain Marvel the year after, so it can’t have been too bad at that time.

LikeLike

Thank you! Haven’t seen any of the non-Karloff ‘Mummy’-s, but your reviews (as usual) have roused my curiosity.

LikeLike

Tana leaves used in the Mummy movies were actually Eucalyptus leaves. No such thing as Tana leaves, made up for the movies.

LikeLike

Given how many eucalypts there are in California, no wonder they used the dratted things! 😄

LikeLike

Pingback: ‘The Mummy’s Ghost’ (B-Movie Review) — Part One | I Found it at the Movies

I found myself genuinely amused by this film’s Odious Comic Relief at times. Should I seek professional help?

LikeLike