“I declare that I receive 100,000 golden coins; in exchange I give to Mr Scapinelli the right to take whatever he wants from this room…”

Director: Stellan Rye and Paul Wegener (uncredited)

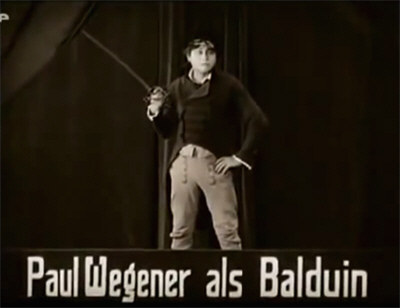

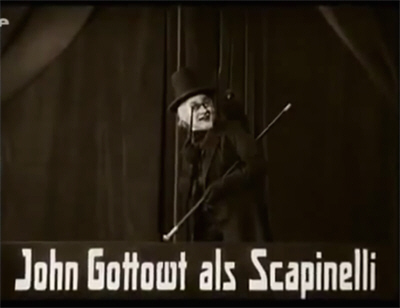

Starring: Paul Wegener, John Gottowt, Grete Berger, Lyda Salmonova, Lothar Körner, Fritz Weidermann, Alexander Moissi

Screenplay: Hanns Heinz Ewers

Synopsis: Though celebrated as the best swordsman in Prague and popular amongst his fellow students, Balduin (Paul Wegener) has been reduced to a state of poverty. In his depression of spirits, he refuses to join in his friends’ carousing, and shuns the advances of Lyduschka (Lyda Salmonova), a dancing girl who loves him. As he sits apart from the crowd, Balduin is joined by a stranger called Scapinelli (John Gottowt), who intimates that he might be able to help him. Balduin retorts that the only thing that could help is a winning lottery ticket or a rich wife. Scapinelli continues to hint that there might be something he can do, and the two men walk off together… The Countess Margit Schwarzenberg (Grete Berger) is reluctantly engaged to her cousin, the Baron Waldis-Schwarzenberg (Lothar Körner), who is also her father’s heir. While the two are riding to hounds, the Baron takes Margit aside. She tells him bluntly that she does not love him; while she is struggling to get away from him, her horse bolts. As it gallops down the road, it passes Balduin and Scapinelli; the former hurries after it, in fear for the rider’s safety. Finally reaching the banks of a river, the horse throws Margit into the water. Balduin dashes in and carries her back to dry land. Immediately, some of the hunters arrive, alerted to the danger to Margit by the Baron, who thanks Balduin for his efforts. Balduin, smitten by Margit, reluctantly surrenders her… Later, Balduin pays a formal call upon the Graf von Schwarzenberg (Fritz Weidermann), Margit’s father. Margit is delighted to see the young man and welcomes him warmly, but retreats into her shell when her cousin appears. The arrival of the Baron prompts a disappointed Balduin to cut his call short. He is gloomily contemplating his situation in his barren rooms when Scapinelli arrives. Scapinelli explains that he has come to make a bargain with Balduin, and astonishes him by pouring from a purse more gold coins than it could possibly hold. Excited but suspicious, Balduin demands to know Scapinelli’s terms, laughing incredulously when he is offered one hundred thousand pieces of gold in exchange for any one item that may be found in his rooms. Balduin signs the contract without hesitation, then waves a hand at his bare walls, inviting Scapinelli to makes his choice. To his bewilderment, Scapinelli demands his reflection—and Balduin can only stare in horror as it steps out of the mirror and follows Scapinelli from the room…

Comments: While designating “the first” of anything is always tricky, there is no doubt that the 1913 version of The Student Of Prague was amongst the very first attempts to tell a full-length horror story on screen. The film was the brainchild of Paul Wegener, who unlike many of his fellow stage actors grasped the potential of cinema from the first, particularly the options offered by special effects. In this respect he found a sympathetic collaborator in Hanns Heinz Ewers, who may be best known these days as the author of Alraune, but was notorious in his own time equally for his peculiar personal philosophy and his espionage activities. At Wegener’s behest, Ewers came up with a cinematic take on the German legend of the doppelgänger, creating a scenario that blends E. T. A. Hoffmann’s short story Die Abenteuer der Sylvesternacht with Poe’s William Wilson, and with a smattering of Faust thrown in for good measure.

Meanwhile, to direct his film Wegener hired the Danish Stellen Rye, who earlier the same year had directed him, Grete Berger and Lyda Salmonova – all graduates of Max Reinhardt’s stage company – in his first film, Der Verführte. The two men worked closely together on The Student Of Prague, so closely indeed that Wegener is commonly listed as the film’s co-director.

(Rye had fled Denmark for Germany after serving a prison term for homosexuality. In 1914 he enlisted to serve in his adopted homeland’s army, and died as a POW.)

Paul Wegener meant The Student Of Prague to be a cinematic landmark, and in this he was supported by the film’s production company, the Deutsche Bioscop Gesellschaft. Advertising declared the film to be an attempt at “great, serious dramatic and literary art”; the pianist Josef Weiss, a student of Franz Liszt, was hired to write a score – the first ever written specifically for a film – to be played at its premiere, which took place at the Mozart-Lichtspiele cinema in Berlin on the 22nd August, 1913.

Both because of these then-unique promotions and its own significant artistic virtues, The Student Of Prague was a huge success. Almost immediately, a slightly-shortened English-language version was prepared for export: the beginning of a history of tampering with the film that would go on for nearly a century. The next significant step occurred in 1926, when a remake starring Conrad Veidt was produced, and the distributor to whom the rights to the Wegener version had passed re-released it—but not in the same form. Wegener and Ewers had made the deliberate artistic choice to keep their intertitles to a minimum, intending that the acting and visual effects should tell the story. The distributor, however, responding to the perceived needs of audiences of the 1920s (and possibly foreshadowing the imminent shift to sound films) inserted an astonishing 107 new intertitles, trimming the film in the process and, between the two, completely destroying its rhythm.

Meanwhile, around the world, The Student Of Prague was being cut and cut again—also in response to the perceived preferences of local audiences—while the accompanying intertitles were translated from German to English with more haste than care. Finally, in English-language territories, all that remained was a poor quality, 41-minute-long, black-and-white version of Paul Wegener’s 85-minute, tinted original.

And so it would remain until, in preparation for the film’s 100th anniversary, a restoration was undertaken by the Munich Film Museum. A copy of the re-titled 1926 version was hunted out, and nitrate fragments of the film were tracked down in storage all over the world. Amazingly, 83 of the original 85 minutes (which included a musical intermission) were finally found, including the long-missing prologue featuring Wegener and Ewers contemplating the city of Prague from across the river; with short interludes of black-screen left to indicate where something was missing. A score was added that drew upon Josef Weiss’s work, and the original tints and few intertitles were replaced. The restoration was released to DVD in 2016.

While the commonly available 41-minute version of The Student Of Prague is a visual abomination, it represents a surprisingly intelligent piece of editing. Though every scene has been truncated, not a single major plot-point is missing; there is not a single moment when the viewer left to scratch their head and wonder what just happened. That is the best we can say for it, however: this choppy, simplified version only hints at the artistry of the original film, and its remarkable special effects; both extraordinarily advanced, considering the film’s production date.

For those familiar with the early days of horror cinema, the other striking thing about The Student Of Prague is its seriousness of tone. There is not a breath here of the nervousness that pervades so many of the early American and British horrors, no comic relief, no deliberate undercutting of atmosphere; not even a contrived happy ending.

Indeed, one of the greatest attractions of the silent German horror films is exactly this gravity, the unhesitating way in which they demand to be taken seriously. Perhaps this is not, upon reflection, so surprising: the Germans were the first to embrace an unabashed horror literature, when everyone else was explaining away their supernatural manifestations via unconvincing tales of banditti and wax figures; it makes sense that their approach to cinema would be the same.

While the production of The Student Of Prague in 1913 runs against the convention that the German horror cinema was a by-product of World War I, this film does differ markedly from its later brethren. Whereas the next wave of German horror embraced the concept of Expressionism, Paul Wegener was interested in emphasising the difference between the stage and the screen. In this he is not always successful, though some of this may be due to the technical limitations of the time. The film’s indoor scenes nearly always play out in front of a single, static camera; however, its outdoor scenes offer movement of the camera itself, action within the frame, and even depth of focus. Cinematographer Guido Seeber builds atmosphere via chiaroscuro; while the location shooting in Prague – including in the Lobkowicz palace – grants an increased sense of realism. Wegener was unable to gain access to one of his most important settings, however, being refused permission to film in the famous Jewish cemetery. (It’s interesting that he thought to ask, respectful behaviour uncommon in the early days of film.) His response was not to create an entirely synthetic setting, but to have reproductions of a number of headstones, Hebraic inscriptions and all, placed within the shadowed margins of a real forest.

While concentrating upon the effectiveness of his sets, it is possible that Paul Wegener did not give sufficient attention to another difference between the stage and the screen: namely, that what you can get away with on one doesn’t fly on the other. Wegener was thirty-nine when he cast himself as Balduin, and it shows. His overall performance is good, but he convinces neither as a hell-raising student nor as a first-class swordsman. Still, on the whole he comes off rather better than the unfortunate Grete Berger, who plays the Countess Margit. Berger was only thirty when she made The Student Of Prague, but was so unflatteringly photographed that quite often she looks a good ten years older than Paul Wegener, and sometimes old enough to be his mother. The scenes featuring the two “young lovers” are uncomfortable at best, and occasionally embarrassing.

Conversely, the outstanding piece of casting in The Student Of Prague is John Gottowt as Scapinelli. His scenes are few, but unforgettable; and, moreover, possibly represent the first instance of the persistently popular depiction of Satan as a deceptively good-natured con-artist. It is not surprising that his performance proved influential, with echoes of it to be found in other films for many years to come. Some have detected anti-Semitic overtones in Gottowt’s characterisation, but I cannot say these are evident to me. I think, rather, that this interpretation is a retroactive consequence of the way that characters like Scapinelli were used in later films.

The opening of The Student Of Prague plunges us right into Balduin’s problems. While his fellow students drink beer and carouse, he sits gloomily on his own, considering his empty pockets. He responds neither to his friends’ toast – “A health to Balduin, Prague’s finest swordsman and wildest student!” – nor to the advances of Lyduschka. Who exactly Lyduschka is, is one of the film’s little mysteries. A direct translation of the original German intertitles has her “a daughter of travel”, usually interpreted as “a wandering girl”; some reviews call her “a gypsy”; while I’ve gone with “a dancing-girl” on the grounds that the first thing we see her do is dance on a table.

Lyduschka is, in any event, cast in the mold of Cigarette, from Ouida’s Under Two Flags (first filmed in 1912, significantly enough): a good-time girl who is popular with all the boys but who loves only one, and the corner of a burgeoning romantic triangle, self-evidently doomed to lose out to her aristocratic rival. We get no sense here if there was ever anything serious between Balduin and Lyduschka, but know only that at this moment he has more urgent things on his mind than romance.

A carriage pulls up outside the Biergarten, and Scapinelli climbs down. He makes his way to Balduin’s table with suspicious promptitude. Balduin is irritated by the intrusion and shows it, but lends an involuntary ear to the stranger’s hints of financial assistance. At last the two seal a bargain of some sort with a firm handshake, before strolling off together while Lyduschka looks on worriedly.

Meanwhile, the Countess Margit Schwarzenberg is joining the hunt in company with her cousin and fiancé, Baron Waldis-Schwarzenberg. The Baron is the last of the family name, and the fears for his line have prompted the Graf von Schwarzenberg to compel his daughter into an engagement, much against her will. The Baron succeeds in separating himself and Margit from their companions, but she is blunt in spurning his advances: “Cousin, I obey my father’s will, but I love you not!”

One of the film’s most problematic sequences follows. First, we are presumably to understand that Margit’s horse bolts with her, although there is no reason why it should and no indication that she isn’t in control of her mount. However, when it canters down the road past Balduin he reacts as if Margit is in grave danger. Then there is a cut of sorts to the horse standing in the river, at which point its rider falls off: we presume she is supposed to have been “thrown”. Likewise, we are expected to believe that Margit is at risk of drowning despite the fact that the water can be only a couple of feet deep.

(The horse calmly drinking nearby, the river barely topping its hoofs, does little to increase our sense of Margit’s peril. Perhaps this is why the animal disappears between shots.)

Be that as it may, Balduin plunges in to the rescue, and—

Ahem. Gerte Berger was, uh, not insubstantial, even when not fully clad and sopping wet; plus she was properly costumed in the bulky female clothing of the period. Consequently, Balduin’s struggle to pick up Margit and carry her to shore looks a little too genuine to be comfortable. He gives up in the end, settling for walking her out. He has barely laid her down when the Baron and some of the others arrive and reclaim her, and in spite of the Baron’s fervent handshake Balduin finds himself thrust aside. This brief passage has been enough to infatuate him with Margit, however, and adds another layer of misery to his money woes, as he contemplates the distance between penniless student and rich Countess.

Despite her apparent state of shock, Margit managed, “surreptitiously”, to slip her “amulet” (locket) into Balduin’s hand, presumably to let him know who she is and where to find her. Back in his rooms, whose barren state reflect his financial woes, Balduin practises fencing in front of his mirror before responding to Margit’s tacit invitation and calling upon her.

(This is the only time in the film that we see “Prague’s finest swordsman” in action.)

Balduin finds Lyduschka loitering outside of his lodging-house: it is unclear to the viewer whether she is paid for her dancing, but we do learn that she derives a small income from selling bouquets of flowers. Here, Balduin offers to buy one, but instead she presses it upon him as a gift. This does not dissuade him from his intention of re-gifting the flowers to Margit—so perhaps it serves him right that the Baron shows up almost immediately with a much more impressive bouquet. Despite the fact that Margit was evidently pleased to see him, and is even more evidently displeased to see her cousin, a hang-dog Balduin soon withdraws from the scene (not even leaving his flowers!) and returns home to brood.

Scapinelli was an interested spectator of the scene at the river, and his gleeful reaction to Balduin’s pursuit of the endangered Margit, as the two men just happen to be walking down that particular road at that particular moment, hints at a plot deeply and carefully laid. The viewer is therefore not surprised when, at this psychologically critical juncture, Scapinelli turns up again, letting himself quietly into Balduin’s rooms.

(Balduin’s reaction here suggests that the door was locked.)

Scapinelli has come to make a bargain with Balduin; in fact, he has brought a written contract. Before he shows Balduin its contents, however, Scapinelli shows him something else. He pulls a small purse from his pocket and begins to pour gold coins out of it onto the table—far more than the purse could realistically hold…

This is the first of the film’s special effects sequences, and perhaps the least successful: small jump cuts make it clear how the multiplying money was achieved. But something much better soon follows…

Balduin is too dazzled by the sight of all this gold to worry about a little detail like where it’s coming from, and when Scapinelli follows up his first display by pulling handfuls of paper money out of his pocket and scattering them around, the student is almost past caring what the contract says. When he does finally read it, it seems absurdly generous: any one item of Scapinelli’s choosing, to be found in Balduin’s rooms, in exchange for one hundred thousand gold coins; enough to court a Countess on. Balduin’s immediate reaction, as he glances around his barren surroundings, is a derisive laugh; he signs the contract without hesitation.

And Scapinelli laughs too, as he strolls up to the mirror. He gestures, and both Balduins – the corporeal Balduin and his reflection – drop their copies of the contract; but only one of them steps forward…

The doppelgänger effects in The Student Of Prague, though chiefly the product of simple split-screen work, are remarkably effective. The two Balduins confront each other time and again with few errors in lighting or any blurring of the image to give away the trick. The result not only outdoes any comparable contemporary film, but offers a serious challenge to many later, infinitely more technically advanced productions. (I’m thinking here of something like The Dark Mirror, where there is never not an obvious visual “line” between the two Olivia de Havilands.)

As he watches Scapinelli and his part of the bargain depart, Balduin tries to laugh again, but it is a feeble effort that does not outlast his first glance in a mirror. Then he shrugs: what is a reflection compared to more money than he ever dared dream of…?

Balduin’s social fortunes are soon looking up as well. He is invited to a ball at the Governor’s mansion, and dons his expensive new clothes before setting out in his expensive new carriage, driven by his expensive new servants. On the road, he meets Lyduschka and buys a bouquet from her, tossing a careless handful of gold coins into the road before driving off.

Lyduschka gathers up the coins, staring after him, and this evidence of his affluence, in confusion and dismay—and then follows him. We see her next infiltrating the grounds surrounding the Governor’s mansion, undertaking several dangerous climbs before reaching a balcony from where she may see the ball.

(As the film progresses, Lyduschka’s ability to come and go among the homes of the Prague elite grows increasingly improbable.)

Margit is also attendance at the ball. She again shows her pleasure at Balduin’s company, and allows him to coax her out for a stroll along a long, moonlit cloister. There, he declares his feelings for her.

Three different people take a great interest in this interlude, and one of them shows himself without loss of time: the Baron stalks up to reclaim Margit, who allows herself to be led away. As she goes she drops her scarf, accidentally or otherwise. Balduin scoops it up and then scribbles a note, which he tucks inside the garment. This manoeuvre is observed by the jealous Lyduschka.

Despite the interruption of his tête-à-tête with Margit, Balduin wanders along in a happy daze—which lasts until he encounters the third of the interested parties, his reflection, who sits perched upon the balustrade and who fades away even as the startled Balduin draws near.

Balduin is still recovering from the shock when he approached by two of his friends, who notice his perturbation. One of them (we gather) remarks that he looks like he’s seen a ghost—and offers him a mirror so that he can see for himself…

After a quarrel with her angry fiancé, Margit leaves the ball. Balduin is waiting in the road, and returns her scarf—of course handing her also the hidden note. Lyduschka, hovering as always, observes this, and quickly hops up onto the back of Margit’s carriage. She is therefore on the scene and spying again when Margit finds the note, which confirms an assignation made between herself and Balduin.

(In the Jewish cemetery, at eleven o’clock at night! – on the grounds that it is “the most discreet place in Prague”.)

Lyduschka manages to infiltrate Margit’s room, where she seizes both the scarf and the tie-pin that Balduin used to secure the note: an affectation which, unfortunately, he showed off to the Baron upon his arrival at the ball. She also follows when a nervous Margit slips away to keep her appointment with Balduin. Lost in her own thoughts, Margit does not notice; nor does she recognise the elderly man in a top hat who accosts her along the way—though she instinctively crosses herself when he speaks to her.

Margit’s fears are soothed when she finally meets Balduin. They stroll hand-in-hand through the woods, and are about to share a first kiss when Balduin realises that they are not alone. He recoils in fear, Margit in embarrassment—and then shock as she realises that the intruder is her lover’s double. Balduin hurriedly sends her away, then turns to confront his reflection, but it has already vanished…

Meanwhile, a vengeful Lyduschka has made her way to the residence of the Baron—who must have the world’s worst-trained manservant in his employ, as he shows the girl in rather than slamming the door in her face and/or releasing the hounds.

Lyduschka gives the Baron the scarf, with the compromising pin attached, and tells him what’s going on behind his back. The Baron affects to treat her story lightly and dismisses her with a contemptuous offer of payment; but as soon as Lyduschka has gone he breaks into a rage. There is only one possible response to Balduin’s misconduct, and the Baron gives it: he challenges Balduin to a duel.

As we recall, the whole point of the Graf von Schwarzenberg forcing Margit into marriage with her cousin was survival of the family line; so the news that the Baron will be crossing swords with “the finest fencer in Prague” is all of the Graf’s nightmares come true at once. He pleads with his nephew not to go through with it, but the Baron refuses to back down. The Graf then carries his plea to Balduin himself, begging him not to kill his opponent. Balduin has, of course, every reason in the world to want to be in the Graf’s good graces, so he willingly pledges his word that he will not take the Baron’s life. The two men solemnly shake hands.

The Student Of Prague’s most indelible moment follows. On the morning set for the duel, Balduin sets out for the isolated location chosen for the encounter. As he walks into the margin of the forest, he meets his reflection, coming in the other direction. Balduin stops, recoiling involuntarily, and can only stare in horror as the reflection, with great deliberation, wipes the blood from his sword…

The death of the last of the Schwarzenbergs, in concert with Balduin’s apparent violation of his word of honour, ruins him utterly with the Graf, who bars his doors to him. Cut off from Margit, Balduin tries to forget his troubles with a little debauchery, but can’t even work up enough spirit to dance with Lydushka, who turns up in clear expectation of finding her way back to him cleared. Instead, she is punished as perhaps she deserves, when an impatient Balduin shrugs her off and throws a few insulting coins at her feet.

Cards are next, and for a time Balduin embodies the old adage about being unlucky in love. One by one, much poorer for the experience, Balduin’s companions flee from him—until the only person willing to play with him is the last person in the world he wants to see. To him, Balduin loses…

In desperation, Balduin decides that he must see Margit, and sets about sneaking into the Schwarzenberg estate. (We note with some amusement he has a great deal more trouble doing so than Lyduschka ever did.) With the help of a convenient ladder, he climbs up onto the balcony outside Margit’s room. She is startled and dismayed by his sudden appearance, ambivalent on her own account but in no doubt whatsoever of what her father’s reaction to this intrusion would be. However, Balduin’s desperate pleas finally soften her heart, and she confesses that her feelings towards him are unchanged. Enraptured, Balduin draws her into his arms and kisses her.

This moment of bliss is Balduin’s last, however. As he and Margit stroll about the room, trying to think of a way to resolve their situation, they happen to pass in front of a large mirror…

But Balduin does have a reflection, of course: in fact, it’s standing over by the window. Margit faints; Balduin flees, retracing his steps to the front gate. As he awkwardly climbs over, the reflection unhurriedly opens and passes through a locked door, so that it is waiting for Balduin on the other side. After one horrified glance, Balduin turns and runs madly from the scene and up a deserted street—which is suddenly not quite deserted. He dashes onwards – and onwards – but he is never alone…

(Some truly lovely location shooting here almost distracts us from Balduin’s nightmarish dilemma.)

In what seems like a stroke of fortune, Balduin stumbles out of the forest onto a narrow roadway just as a carriage is passing. He flags it down and climbs in, peering around anxiously as the vehicle rolls on again; but he has, it seems, finally eluded his pursuer. It is not until the carriage reaches town that he sees who the driver is. With a wild cry he runs home, only to find that he has been headed off again…

In his rooms – which are expensive, and lavishly furnished, albeit bereft of mirrors – Balduin reaches the last stage of despair. He takes from a cabinet a set of duelling pistols, and contemplates one resignedly. After checking to see that he is truly alone, Balduin sits down to write a letter—and it is then that his reflection crosses the room towards him.

With a cry Balduin leaps to his feet, snatches up his pistol, and fires at his infernal companion…

Though it is not without its crudities and shortcomings, some of them of them unavoidable at the time, The Student Of Prague is a truly remarkable achievement: one which, thanks to the care and dedication of those involved in its restoration, modern audiences are now in a position to appreciate for the first time. Visually, the new prints are a revelation; and although the edited version did not entirely cut anything, it shortened everything, leaving behind a crude rendering of the story bereft of all detail and some explanation.

Almost every scene benefits—even those which were not previously cut, such as when a card-playing Balduin looks up and realises that he is gambling against himself. My favourite new touch, however, is the clarity of the moment after the duel when, recoiling from the nightmarish vision of his double, with its bloody sword, Balduin finds himself confronted by the distant sight of the seconds and the doctor gathered around the dead body of the the Baron Waldis-Schwarzenberg, as it lies in the meadow-land dueling-ground.

The Student Of Prague marked Paul Wegener as one of the true visionaries of the dawn of cinema. Wegener would continue to dabble in tales of the supernatural throughout his career, both as an actor and a director, and play a vital role in the development of German Expressionism. And to return to my earlier point— While there is absolutely no denying the cinematic power of the German horror cinema of the silent era, the single most striking thing about it, at least to those well-versed in early horror, may well be its mood—its seriousness, its willingness to disturb its audience. The Student Of Prague is a case in point: an extraordinarily sombre work, which far from somehow extracting a happy ending from its tale of spiralling misery, gives Scapinelli the final word. Evil not only triumphs here, but does so gloatingly, with a spring in its step and a laugh upon its lips. The emotional and philosophical distance between this film and the comparable American and British productions of the time is staggering to contemplate.

♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦

This review is part of the B-Masters’ examination of the early days of horror cinema.

Hans Christian Andersen wrote a story similar to this, where the man’s shadow comes to life (no contract with the devil involved, though). The shadow becomes engaged to a princess, and the man is executed (since everyone thinks he is the shadow).

“Now pleasant dreams, sweetie!”

LikeLike

I don’t remember that story, but it sounds like typical Andersen.

LikeLike

It’s interesting to see how the story of doppelgänger is worked out in various contexts—and how often the horror lies in the suggestion that the shadow has more substance than the man.

Hmm, thought: is anyone aware of a female-focused doppelgänger story?

LikeLiked by 1 person

I did read a story where a woman thought she had a doppelganger. I thought it was a Lord Peter Wimsy story, but I tried to look for it just now and couldn’t find it.

SPOILER ALERT: It was really her previously unknown (male) cousin, who ended up killing her, for the inheritance she didn’t know she was in line for.

There was one interesting note. Her “doppelganger” passes her on the stairs, and it has no odor, which confirms her belief in the supernatural. The detective deduces that it (or he, if you prefer), is actually wearing her perfume, since he claimed one cannot smell one’s own fragrance. Which would explain how those people on the bus and subway can live with themselves.

LikeLike

What came to mind belatedly for me was of course Maria in Metropolis. While she’s an artificial and deliberately constructed doppelgänger, the robot functions much the same way in-film.

LikeLike

Wonderful review as always, Lyz! This reminded of the equally well-restored print of ‘The Cabinet Of Dr. Caligari’ I saw at the Goethe-Institut Rotterdam in 2011. It was a breathtaking experience!

LikeLike

Thank you!

Oh, that must have been an amazing experience—I’m very jealous! 🙂

LikeLike

This sounds like a remarkably clever horror movie ( I believe the main source of inspiration would be Chamisso’s Peter Schlemihl. )

LikeLike

Except I think that has the character doing everything knowingly, rather than being tricked? (Not that Balduin shouldn’t have realised that something was hinky…) But the doppelgänger was so ubiquitous in Germanic literature, you can’t point at a single inspiration.

LikeLiked by 1 person