“I wonder if they are imitators? Perhaps their will has been subdued; perhaps they’ve been possessed by another personality, a powerful, malignant personality without – well – without a body of its own…”

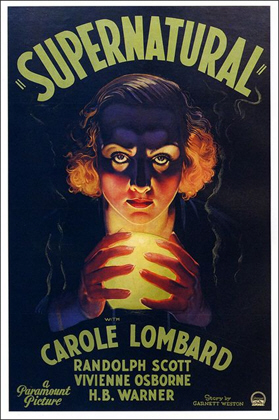

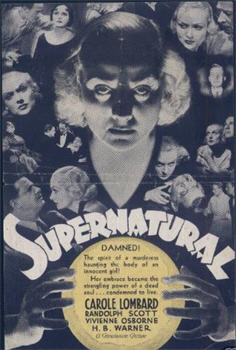

Director: Victor Halperin

Starring: Carole Lombard, Vivienne Osborne, Alan Dinehart, Randolph Scott, H. B. Warner, William Farnum, Beryl Mercer, Willard Robertson, Lyman Williams

Screenplay: Harvey Thew and Brian Marlow, based upon a story by Garnett Weston

Synopsis: Having been convicted of strangling three of her lovers, Ruth Rogen (Vivienne Osborne) is sentenced to death in the electric chair. She is unrepentant and shows no fear as her execution draws near, displaying emotion only upon the question of whether a letter to a man called Paul Bavian has been delivered. Shortly before the execution, Dr Carl Houston (H. B. Warner) calls upon the prison warden (Willard Robertson), warning him that Ruth may be more dangerous after her death than she is now. As the sceptical warden listens, Dr Houston explains his theory of “copycat crimes”: that they are not merely deliberate repetitions of high-profile cases, but actually influenced from beyond the grave… When Dr Houston requests possession of Ruth’s body after her execution, as a subject for his experimentation in this area, the warden takes him to her cell. Ruth is at first hostile and orders the men away, but when warden intimates that Dr Houston may have the power to bring her back after death, she agrees that the psychologist may have her body. As the men leave her, she begins to laugh hysterically—and crushes a metal cup in one hand… A shadowy figure breaks into the mansion owned by the Courtney family, and penetrates the parlour where the body of young John Courtney lies in state. The intruder sets to work inside the coffin… On his way home, Paul Bavian (Alan Dinehart) buys a newspaper: the headline story is Ruth Rogen’s vow of revenge against the man who betrayed her to the police. As he reads, Bavian is accosted by his intoxicated landlady, Madame Gourjan (Beryl Mercer), who asks if he intends visiting Ruth in prison, and scolds him for his shoddy treatment of her. In her own room, Madame Gourjan begins to sort her lodgers’ mail—and opens one letter to see the contents for herself. It is, as she surmised, from Ruth Rogen; in it, Ruth begs Bavian to let her see him one last time… In his room, Bavian is completing work on a death-mask of John Courtney when Madame Gourjan brings his letter in. Seeing immediately that it has been resealed, he insists to Madame Gourjan that Ruth is wrong: he did not betray her. His landlady only laughs, commending his common-sense in not going anywhere near Ruth’s hands… After the funeral of John Courtney, his twin sister, Roma (Carole Lombard), her fiancé, Grant Wilson (Randolph Scott), and the Courtney family lawyer, Nick Hammond (William Farnum), return to the mansion. They are accompanied by Dr Houston, an old family friend. After Roma withdraws to her room, the men worriedly discuss ways to help her through her grief. Upstairs, Roma goes reluctantly into John’s bedroom, touching his possessions gently and consoling his dog. She does not see the spirit of her brother, which hovers near to her… The maid brings Roma a letter. It is from Paul Bavian, who identifies himself as a spiritualist, and insists that he has been contacted by her brother, who has a message for her… Downstairs, the men discuss Ruth Rogen’s execution, at which Dr Houston was present; Houston comments grimly that Ruth may be more dangerous now than she was in life…

Comments: White Zombie was a surprise hit in 1932, bringing its distributors, United Artists, a significant return on a small investment. This did not go unnoticed by the other studios, and towards the end of the same year the producer-director team of Edward and Victor Halperin were offered a deal with Paramount for their next movie, an arrangement which afforded them access to better facilities and far more elaborate sets than had been possible on their previous production’s tiny budget.

That, however, is almost where the good news ended for the Halperins. They had wanted to re-cast Madge Bellamy, their leading lady in White Zombie, in their new film, but Paramount stepped in. The studio insisted instead upon the starring role in the production now called Supernatural being taken by a young actress who, in her struggling early days at Fox, had used her real name of Jane Peters—but who at Paramount had been given the more stylish moniker of “Carole Lombard”.

Lombard was an unusual figure in early Hollywood. She had made a point of learning the technical side of movie-making, and knew more about camera-work and lighting than quite a few directors. (Lombard’s self-consciousness regarding the scar on her left cheek, the result of a car accident, made her sensitive to how she was lit and shot.) She also had very firm ideas about what sorts of films she should be making—and that did not include horror movies. Dismayed in the first instance by her proposed casting in Supernatural, once she had read the script Lombard began an unsuccessful fight to avoid making the film; and in the end it was only threats of suspension from Paramount that kept her toeing the line—and that only up to a point.

Stories abound these days about Carole Lombard, many having to do with what seemed a most jarring contradiction: the combination of her beauty and elegance with an extraordinarily foul mouth. Interestingly, the latter seems to have had little negative impact upon her career: thanks to her more positive qualities – her talent, professionalism and sense of humour – she remained a popular figure, to the extent of various crew-members requesting to work with her; while her vulgarities were generally shrugged off with, “Oh, that’s just Carole.” Victor Halperin, however, might have begged to disagree. During the making of Supernatural he became the target of Lombard’s frustration and disappointment, being made the recipient of any number of choice epithets. One line in particular has gone down in Hollywood legend:

Carole Lombard: “Who do I have to screw to get off this picture!?”

While it is true that Supernatural was neither a commercial nor a critical success upon its first release, it is, I suspect, rather thanks to that line, and the attitude which prompted it, that the film is so little-known today. While over time all of Lombard’s other films appeared on DVD, including a handful of genuine stinkers from her early days, no-one showed any interest in an official release of Supernatural; though it did, thankfully, finally see the light of day as part of the Warners Archive Collection.

Was Carole Lombard justified in her criticisms? Yes and no. Supernatural is a film you would tend to classify as “interesting” rather than “good”…but it is very interesting.

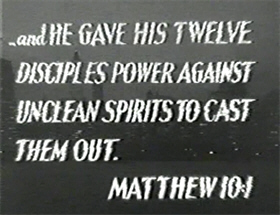

Though we now tend to think of the early 1930s as “the Golden Age of Horror”, we also need to keep in mind that there was still a lot of resistance to the genre—and to supernatural horror in particular. The moral guardians disapproved of them, and the critics tended to scoff at them as demanding too much of “credulity”.

This background makes the opening of Supernatural even more striking: set against crashing lightning and raging seas, a series of titles offer passages to illustrate the fact that only do all religions believe in life after death, but that they believe to in the existence of malevolent undead beings. We get a quote from the bible, and another from Mohammed—and one from Confucius, apparently doing duty for all the rest (“Miscellaneous,” as Reverend Lovejoy would put it).

These titles then give way to something still more startling: a virtuoso opening that employs montage and double-exposure and lighting effects to unnerve the viewer and to provide an admirably summarised version of the film’s back-story.

And it does more: it reminds us bluntly that we are in the pre-Production Code era, offering us not just murder with unabashed sexual overtones, but one of the screen’s first female serial killers.

Evidently a “Black Widow”-type killer, Ruth Rogen has been convicted of strangling three of her lovers to death, each one after – and I quote – a riotous orgy in her sensuous apartment. As we see flashes of the trial, of Ruth Rogen’s deadly hands, and of the prison bars which now restrain her, we also hear her hysterical laughter and snippets of her shrieking testimony:

“He’s lying!…I’ll kill him!…I’d do it again – and again – and again!…Men: I hate the whole breed!…No, I’m not sorry…One week more…Three more days; one for each man…”

Against this is set the ruling on Ruth’s sanity, which paves the way for her to die in the electric chair. Frankly, this comes across more as a determination to consider Ruth sane so that she may be executed than as actual belief; because on the evidence presented to the viewer, this woman is battier than a cave in Texas.

In her cell, counting down her last hours, Ruth laughs at her looming death as she laughs at all else; displaying distress only when asking whether her letter has been mailed: a letter to a man called Paul Bavian. “Why doesn’t he come, why doesn’t he come?” she moans, wrenching unavailingly at her prison-bars.

This powerful opening then gives way to a subplot which is simultaneously one of Supernatural’s most intriguing aspects, and one of its weaknesses—the latter, because of the absurdly off-hand manner in which it is treated.

On the day before Ruth’s execution, eminent psychologist Dr Carl Houston calls upon the warden of the prison to ask a tiny favour: namely, possession of her dead body.

Houston then goes on to explain his belief that, in some cases, the personality – the will – of certain individuals is so powerful, it lives on after the body is dead and can possess another person. To this Houston ascribes the occurrence of copycat crimes, which tend to follow high-profile and unusual cases. He adds that, by experimenting with Ruth’s body, he hopes to prevent this from happening—and to receive negative proof of his theory, at least, if it does not.

The warden is not in the least convinced, but he agrees to let Houston talk to Ruth about it. His arguments carry no weight with her; least of all his suggestion that his experiments will “do something for humanity”, which provokes only sneers:

Ruth Rogen: “My body’s my own! The law gives me that much!”

Those were the days.

Houston is about to give up when the warden intervenes—not, it must be said, in the most ethical of ways, as he intimates obliquely to Ruth that Dr Houston may be able to bring her back after death…

That gets Ruth’s attention, as you might imagine: she contemplates coming back – walking and talking again – using her hands. And as this thought occurs to her, her right hand closes on a metal prison-cup, crushing it…

We then cut to away to a mansion all in darkness, and watch a shadowy figure breaking in. The man makes his way into a flower-strewn sitting room, where the body of twenty-four-year-old John Courtney lies in state. The intruder gets quickly to work, mixing up some thick liquid and smearing it over the face of the dead man… Afterwards, we see the same man striding along with a paper-wrapped package under his arm. He stops to buy a paper, the front-page story being Ruth Rogen swearing vengeance against the man who betrayed her to the police. He is still engrossed when a small, shabby figure staggers up to him.

Beryl Mercer made a career out of playing saintly mothers and put-upon servants, and she clearly found the cheerful, vulgar, drunken Madame Gourjan a refreshing change. She’s the film’s Comic Relief: I’ll refrain from calling her “Odious”, though a little does go a long way, because of the way she balances this aspect of her character with her role as—well, not as Bavian’s conscience, exactly, but his tormentor. This is a man whose entire profession consists of fooling people – who even, we gather, took in Ruth Rogen – but the perpetually inebriated Madame Gourjan sees right through him—and lets him know it.

Furthermore, Madame Groujan is the only person in the film who seems at all interested in Ruth Rogen as an individual; even expressing sympathy for her, in the face of what she knows has been her mistreatment at Bavian’s hands.

“Been to see her in jail, Mr Bavian?” she inquires as she looks over his shoulder at the newspaper. She continues to talk as she pursues him up the stairs, striking at him repeatedly like a more than usually annoying mosquito. He finally escapes into his rooms—and at this point we see the professional sign that hangs outside: PAUL BAVIAN SPIRITUALIST.

(Another reminder that this is a pre-Code film follows, as we see Madame Gourjan’s own filthy apartment, including cockroaches scuttling over her unwashed dishes. On Joe Breen’s watch, something like that would be considered far too tastelessly realistic)

In her own room, Madame Gourjan pounces on one letter in the pile of her lodgers’ mail. Opening it carefully, she finds it is indeed from Ruth: a pleading, placatory letter, promising forgiveness if only Bavian will come and see her. Resealing the letter, Madame Gourjan carries it up to Bavian, who sees at a glance that she’s been before him. He insists that Ruth is wrong, and that it was not he who gave her away.

Having thrown his landlady out, Bavian gets back to work: preparing the death-mask of John Courtney. We see too a newspaper clipping, reporting the young man’s premature death, the bereavement of his twin-sister, Roma, and the fact that she is her brother’s sole heir.

(I have seen several reviews which claim that John was one of Ruth’s victims, but there is no evidence of that in the film.)

We can probably attribute to Ruth Rogen’s being a woman that the film skips over her execution. We hear about it after John Courtney’s funeral, and after his grieving sister has retreated upstairs. Downstairs, the conversation between Dr Houston, Grant Wilson and Nick Hammond turns to the subject of Ruth when Hammond begins reading out loud a newspaper report of her last moments.

Nick Hammond is one of the odder characters in a film not exactly lacking them. Though we are given no hint that he is not thoroughly competent in his job, nor genuine in his care of Roma, or at least of Roma’s money, his abrasive personality and crass sense of humour are what get thrust upon us. Here, Hammond quickly shrugs off the funeral, demanding sautéed truffles to assuage his bottomless appetite, and changes the subject to Ruth Rogen. He chuckles suggestively when he learns that, not only was Dr Houston present, but that Ruth requested he accompany her on her last walk. Hammond opines that Houston is lucky Ruth is dead, as it seems that she was getting a crush on him—and Ruth’s crushes have a way of turning up dead…

Dr Houston: “She may be more dangerous now than when they had her locked in a cell.”

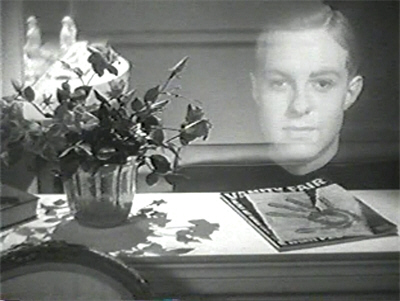

Meanwhile, Roma has forced herself to enter her brother’s room—and as she wanders around, touching his possessions and hugging his dog, we get one of the film’s creepiest touches – because so unexpected – as fleetingly, the spirit of John Courtney shows itself…

Roma does not see it—but perhaps someone else does. If Carole Lombard doesn’t make you tear up in this scene, the dog might, as it trots back and forth bringing John Courtney’s slippers to his armchair. But is it doing this out of habit—or does it know that John is in the room…?

(This turns out to be a rather doggy film: Bavian has one too, though he doesn’t exactly strike us as a pet-person.)

A letter is brought up to Roma. It is from Paul Bavian, and informs her that he has been contacted by her brother, who is distressed about something… Roma goes downstairs to consult the others. A disgusted Hammond stalks off to telephone Bavian, and to tell him off (Bavian hangs up on him in mid-rant); while Dr Houston – after stating that there is, “without doubt”, life after death – adds that he does not believe there can be communication with the dead.

(So…the dead can’t communicate, but they can possess other people and force them to commit murder?)

Left alone with Grant, Roma reveals her firm intention of going to the séance. She asks Grant to accompany her, to which, though completely sceptical, he agrees.

In its way, this is one of the strangest scenes in Supernatural, taking place in a spacious conservatory containing an enormous aviary: strange, because this is a completely thrown-away moment, with no later relevance; we never have the birds reacting to a spirit-presence, for instance. I suppose the set was available, so they used it; but it tends to be a bit distracting. (I should note too that there’s a cockatoo roaming free. I wonder if that’s the same bird that appeared in Mad Love two years later?)

A spying Madame Groujan is unabashed when Bavian catches her at it, instead alluding pointedly to “wires” and “fake messages”. This last is too much for Bavian, who pulls her into his room and shuts the door. As the landlady makes her hopes and expectations clear – that is, a cut of whatever Bavian gets out of Roma – she is unwise enough to add a threat, wondering aloud if she should warn Roma – “Woman to woman.” Bavian has been fiddling with his signet-ring through all this, and as he agrees to a “partnership”, he offers to shake hands—closing his own very firmly about that of his landlady. Madame Gourjan gasps and staggers back, wiping at her own hand in sudden panic and pleading with Bavian that she was only joking, and that he is only joking too, isn’t that right? Joking, maybe not; but Bavian does smile to himself as he watches her die. With time pressing, he then (we gather) uses the train-line that runs outside and below his windows as a handy dump-site.

This bit of business out of the way, the séance may proceed. Roma is fearful yet hopeful, Grant openly contemptuous. Bavian responds to his attitude with practised humility, while Roma begs him to keep an open mind. Once the séance begins, though, we can only side with Grant: the “manifestations” are at first tacky and obvious in the extreme: a disembodied hand, a floating trumpet.

We feel that Bavian has miscalculated, and that a less-is-more approach would have been more effective: just the sudden appearance of the pale face of John Courtney which, when it occurs, is eerie enough; all the more so because when an enraged Grant throws himself in the direction of the apparition, he can find no explanation for it…

Meanwhile, the message delivered, despite Bavian’s preliminary warnings, is clear enough: “Guard yourself. Hammond wants our money. He murdered me…”

An unnerved Roma promises to call Bavian, and then allows Grant to lead her away. As the door closes, Bavian smirks—and retrieves John Courtney’s death-mask from behind a sliding-panel.

In her frightened uncertainty, Roma heads for Dr Houston’s apartment, hoping for his counsel—but interrupts him at an exceedingly awkward moment. Ignoring Houston’s servant, who tries unavailing to keep her out of “the laboratory”, Roma forces herself into a curtained-off section of the apartment just in time to see Ruth Rogen sit up and open her eyes—and then (to the sound of crackling equipment) collapse again.

The collision of off-kilter tones here is enough to do your head in. On one hand we have a classic mad-scientist-in-his-laboratory scene, all strange electronic noises and an accompanying thunder-and-lightning storm outside; albeit that the “laboratory” is situated in a swank penthouse apartment. On the other, Roma and Grant barely react to what they walk in on, displaying mild embarrassment, as at a social faux-pas, rather than shock and horror at the discovery that the respected Dr Houston is experimenting with dead serial killers—and has apparently brought one back to life!?

But, no: it turns out that Grant and Roma don’t recognise Ruth; not big newspaper readers, apparently. Still, that hardly excuses Grant’s puzzled, “Why, doctor – what’s the matter?” when Houston’s stressed and frazzled demeanour dawns upon him. Houston drags a screen across, blocking their sight of the body, then breaks to them the identity of his experimental subject—adding, “You remember the case.”

You mean the one that dominated front pages for weeks and which culminated in the woman’s execution YESTERDAY and that you were discussing THIS MORNING?

And Dr Houston, in fact, is not upset about being caught performing questionable experiments on a corpse: he’s worried about the safety of Grant and Roma, hustling them out of his laboratory with the explanation, “There’s danger of contagion.”

(Um, yes: I’m not altogether sure that two glass doors and a folding screen are sufficient protection against that sort of “contagion”.)

The three then forget about the reanimated corpse, discussing the séance instead. Interestingly, though Houston dismisses the suggestion that Hammond murdered John (though, we now learn, the lawyer was with him when he died), he is not so sure that the rest was necessarily faked. He advises a second séance, but at her house, to test the matter.

Suddenly, a cold wind sweeps through the apartment—despite the windows being closed. Houston again hustles Roma and Grant away, promising to arrange the séance and asking the spiritualist’s name. When Roma replies, “Paul Bavian”, they are startled by a noise from behind them. The three swing around to discover that the screen has been knocked over, and that Ruth’s body, now slumped upon the floor, is now in plain sight.

Houston starts for the lab, but stops again when Roma suddenly moans, clutching at her own throat. A frightened Houston hurries her and Grant into the next room, as the cold wind sweeps through again…

As Roma sinks back upon a couch, Grant is horrified to see finger-marks upon her neck. “Ruth Rogen!” exclaims Houston. “She tried to get possession of Roma’s body! Thank goodness she failed…”

Invited to hold the second séance, Bavian’s first move is to recharge his signet-ring; also preparing a small vial of the poison, which he tucks into his pocket.

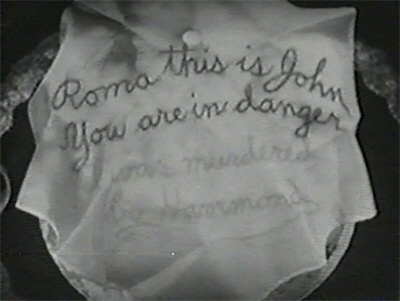

At the Courtney house, Bavian arranges the participants around a globe-shaped light. He explains to his sceptical audience that he will be trying to invoke spirit-writing, which sometimes appears on a piece of cloth spread over the lamp. He takes a handkerchief from Nick Hammond, drawing attention to his use of an item that he could not have pre-prepared—and, under this smokescreen, skilfully substituting one of his own. Bavian then withdraws from the circle, lighting incense before sitting down at the piano.

As Grant switches out the lights, there is a shift in mood. Despite Roma’s distress, Grant, Hammond and even Dr Houston have been exchanging smirks and sneers; but now something changes. Grant becomes serious, Houston uneasy. And then a draft begins to stir the curtains. Roma shivers…and her hand moves up to her throat…

Bavian, oblivious to these unanticipated events, sticks with routine, suddenly slumping over the piano and striking a discordant note on the keys. As he does so, writing begins to appear on the handkerchief:

Roma this is John. You are in danger. I was murdered by Hammond.

At the piano, the seemingly unconscious Bavian takes from his pocket a small portable projector—and suddenly the ghostly face of John Courtney appears in the darkness…

Roma cries out in shock, while a furious Hammond confronts Bavian, grabbing him angrily. This contact allows Bavian to slip a vial into Hammond’s pocket—and to clutch at him back.

Houston intervenes between the two men. As Hammond turns away, still uttering furious threats, the others realise that Roma has fainted. Concerned with her, they do not immediately notice that Hammond, having staggered into the next room, has also collapsed…

As Roma lies unconscious on a sofa, we see the spirit of Ruth Rogen settle over her. In an instant, Roma’s whole demeanour changes; her hands begin to writhe; the eyes which she opens are no longer her own…

One of the – many – things that drove Carole Lombard crazy on the set of Supernatural was the “transformation” scenes. In order to convey those moments when Ruth Rogen was in possession of Roma Courtney’s body, Victor Halperin had Lombard made up as Vivienne Osborne is in the early scenes, darkening her lipstick and her eyebrows, and adding heavier eyeshadow; and to do that, he forced Lombard to lie motionless for hours while she was photographed as Roma, had her makeup applied, was photographed as Ruth, and had her makeup taken off again. We can only assume that no-one associated with this film was aware of how the transformation effects were achieved in Rouben Mamoulian’s version of Dr Jekyll And Mr Hyde!

The thing that is frustrating for the viewer, however, is that it wasn’t necessary. Carole Lombard’s physical performance after Roma is taken over by Ruth makes it perfectly clear who is in charge of Roma’s body at any given moment.

As Roma sits up, Grant is simply relieved, while Dr Houston looks puzzled. It is Bavian, however, upon whom Roma’s attention is focused. As she glides up to the spiritualist, he too is clearly puzzled—but willing enough to accept Roma’s sudden interest in him. Their interaction provokes Grant, who accuses Bavian of trickery and orders him out of the house.

“You keep out of this!” Roma snaps at him, as Grant stares back in shock.

At this critical moment the butler rushes in to announce his fear that Hammond is dying. As Grant and Houston hurry out, Bavian remarks drily, “I think I’d better go.” “Yes,” purrs Roma. “Let’s both go.”

Ah, the male ego! – what a wonderful construct! Nothing in Roma’s change in attitude, or her sudden interest in himself, strikes Bavian as at all unusual. Instead, preening himself, he offers Roma an arm, and the two of them depart. Grant and Houston are too late to stop them but, rushing out after them, Grant gets the license-plate of their taxi.

Bavian is surprised, however, by where Roma leads him: to a block of studio-apartments over a glass-blower’s shop, one of which used to be occupied by Ruth Rogen. The key is still in its slot: Roma helps herself and, with Bavian trailing apprehensively in her wake, makes her way upstairs.

Ruth was an artist, as we are now reminded: various sculptures are placed around the studio, while in the middle of the floor sits a large painting on an easel. It is covered when the visitors enter, but – explaining coolly that the studio, “Belonged to a friend of mine” – Roma pulls away the cloth, exposing a full-length self-portrait of Ruth in which, suggestively, she is cradling an apple.

(Which I guess makes Bavian the snake…)

Bavian tries to avoid discussing Ruth, though he denies being afraid of the subject—or of her: “Why should I be?”

“Some men were, I hear,” says Roma, contemplating the painting. “She told me of one—so much afraid of her, he gave her away to the police.”

After bringing Bavian to admit that he was the man, Roma abruptly switches the topic back to herself, encouraging Bavian to be “less formal”. As he obediently calls her “Roma”, the camera swings to show us another of Ruth’s works, a simpler one: a framed sketch of a black cat; or perhaps it’s a panther: it’s eyes glowing as we saw Ruth’s / Roma’s only moments ago… As she pours drinks, Roma forces the conversation back to Ruth, dragging more admissions out of Bavian; that she was beautiful, yes, but—

“But repulsive,” Bavian says abruptly. “Like—a female spider that kills her mate when she’s through with it. She would have killed me if I hadn’t got rid of her first.”

“You did get rid of her,” breathes Roma. “Aren’t you lucky?”

And her hand closes upon a metal cup, crushing it…

Bavian then turns on the smarm charm. “You do care for me, don’t you, Roma?” he demands. They kiss, and one of Roma’s hands slips up towards Bavian’s neck—but they are interrupted by the indignant caretaker. He orders these “strangers” out of the studio, prompting Roma to throw herself at his throat: “I’ll kill you, I’ll kill you!”

But even this is not sufficient for the penny to drop, and having quieted Roma, Bavian suggests they repair to her yacht—to which, after one blank moment, she agrees. Once there, and assured that they are alone, Roma begins making her move—encouraging Bavian to pour drinks while she locks the door to the sitting-room and hides the key. Bavian, we gather, is something of a lush – as Ruth must know – because a single drink makes his mask slip; and in place of the smooth-talker is a slightly staggering caveman only to willing to be led to a sofa, and—

Ooooooo-AHHHH-eeeeee, pre-Code movies! I commented that in Murders In The Zoo, Lionel Atwill, “All but puts his hands on Kathleen Burke’s breasts.” Here, we lose the “all but”: Alan Dinehart flat-out gropes Carole Lombard, as Bavian and Roma lock into a lengthy horizontal embrace.

Meanwhile, Grant and Dr Houston are dashing around trying to track down the, uh, lovebirds. They find the glass-blower’s, and learn that they were there—in Ruth Rogen’s apartment. Houston becomes frightened when he hears that it was Roma who seemed to be in charge. “It was the other one!” he exclaims in horror—as we see a laughing Ruth superimposed over him and Grant.

Houston collapses with the shock of it—and the guilt. As Grant tends to him, John Courtney’s spirit appears behind him… Grant knows he must find Roma, but has no idea where to start—until a breeze wafts through the room and knocks over a small ship that the glass-blower has just finished. Grant promptly has a Lightbulb Moment©, and rushes off for Roma’s yacht.

Pre-Code or not, Supernatural cannot be absolutely explicit about whether Bavian and Ruth / Roma actually have sex—but it’s as explicit as it could be. When we cut back to the yacht, the two of them are still lounging on the couch, and Roma at least is smoking. Bavian, meanwhile, is sucking down champagne and chuckling like a man who can’t believe his own luck—as of course he should not.

After all—we do know that Ruth likes to mate before she kills…

“You know, Roma,” muses the self-satisfied Bavian, “you’re a lucky girl. You have your pearls – you have your yacht – and you have me.”

Oh, my God! – never mind Ruth: Roma should kill him!

As Bavian beams, one of Roma’s hands snakes out, briefly stroking his hair—and then dropping to his throat…

And that is when the penny does begin to drop. Bavian pulls away; not really understanding but seeing, or at least feeling, enough to be frightened. But to his increasingly frantic questions, Roma responds only, “You’re imagining things.” She insists upon one last drink, and turns away to pour it—and Bavian starts fiddling with his signet-ring.

But it is Roma who moves first, clutching at Bavian’s right hand with a protective cloth wrapped around one of her own, and seizing him by the throat with the other—forcing him across the room and down onto a sofa, snarling as her grip tightens, and tightens…

“I am Ruth Rogen!” she hisses. “And I’m going to kill you before I leave this body you like so much!”

(And, oh dear: for the third time in three consecutive films, the Halperins try the spotlight-on-the-eyes trick—and for the third time, they botch it.)

Bavian is fading fast – we see a blurred Ruth / Roma from his perspective, smiling down at him – when Grant breaks open the locked door. The interruption gives Bavian the chance to break away and run. Grant grabs Roma as she tries to go after him, shaking her and arguing with her as she struggles—until suddenly she is still. She begins laughing, pulling away not to escape, but as if a glorious idea has occurred to her. She crosses the cabin to look out of a porthole…

…and at that moment, Ruth abandons Roma’s body.

Outside, a terrified Bavian is trying to make his escape in the launch which Granted piloted to the yacht—looking over his shoulder as Ruth Rogen’s hysterical laughter pursues him. In his haste and his fear, he struggles to handle the ropes with which the boat is tethered, tangling them and becoming tangled. He looks up, recoiling as if from an incredible vision—

—and then he slips.

Inside, the watching Roma faints. When she wakes up, she is literally herself again—and has no memory of the night’s events.

Just as well.

The term that keeps coming into my head to describe Supernatural is “half-baked”—and that’s not fair, because it conveys no sense of this film’s real virtues.

What it does convey, however, is that the film simply has too many subplots—with only Ruth Rogen’s revenge from beyond the grave being worked out as it should be. All the rest are (Paul Bavian should excuse the expression) just left hanging.

I mean—look at what we have here, in addition to Ruth’s revenge:

- a female serial killer, a literal Black Widow who kills with her bare hands;

- the idea that copycat crimes are in fact committed by the same criminals, their spirits having taken possession of living people;

- an innocent girl being forced to commit murder—and have illicit sex;

- duelling ghosts, with the malevolent spirit of Ruth Rogen being countered by the protective spirit of John Courtney—which none of the characters ever become aware of;

- Nicky Hammond’s “suicide”, brilliantly set up and then just dropped;

- Paul Bavian’s signet-ring: how many times has he used that thing, if Ruth knew to guard herself against it?

- the irony of Paul Bavian as false medium becoming mixed up (all unknowing) with genuine paranormal events;

- and last but definitely not least, Dr Houston’s experiments with the dead—which have enough potential to fuel an entire movie – maybe one of the Boris Karloff mad-scientist films of the late 30s and early forties – but which here are no more than a plot-device! We don’t even know what he does with Ruth’s body once he has it!

All this, in a mere sixty-four minutes!

But if there’s no chance of Supernatural wearing out its welcome, its dangling plot-ends do tend to leave the viewer feeling rather frustrated and dissatisfied. I can’t help wondering if this was initially planned as a longer, “bigger” film. In particular, the clash between Paul Bavian and Nick Hammond – culminating in the latter’s murder – is too fragmentary in its presentation to be effective. There’s no point in the film as it stands at which Hammond poses any real obstacle to Bavian in his pursuit of Roma, and Roma’s money; nor is there any opportunity for Bavian to recognise Hammond as such. Bavian’s framing of the lawyer for John Courtney’s murder, and the staged suicide presumably intended to proclaim his guilt, are excessive even by the standards of someone for whom murder is clearly a regular fall-back.

In fact, it feels as if the middle of the film has been cut quite significantly—which would also explain Dr Houston’s otherwise idiotic remark, “You remember the case?” A lot more time was meant to have elapsed, I think, than is evident in the existing film. And perhaps during this time there was more contact between Roma and Bavian, making their eventual connection less absurdly abrupt.

(To this argument I might add that I’m sure I once read a review of Supernatural which – perhaps from false memory, or maybe from reading the original screenplay? – claimed that Roma did kill Bavian while possessed, and then had to be defended on the grounds that she was literally not herself—presumably via a demonstration by Dr Houston. While I do like Supernatural a lot, I’m kind of sorry we didn’t get that film.)

But whatever the Halperins might originally have intended, and whatever the shortcomings of the completed film, Supernatural nevertheless stands out amongst the first wave of American horror for its contemporary setting, its straight-faced approach to horror, and the audacity of its plot—and for the way in which it is dominated by its female performances.

The men, indeed, fare poorly here: Randolph Scott is wasted in a role that asks him to do no more than stand around looking worried; the part of Dr Houston is too under-developed for H. B. Warner to do anything with it; and Alan Dinehart, though successfully projecting the calculating cynicism of the fake medium, and convincing as an habitual murderer, lacks the sexual charisma we would expect from a man whose business is taking advantage of women.

But this is relatively unimportant beside what Vivienne Osborne and Carole Lombard bring to the film. It is easy enough to criticise Osborne’s performance as too over-the-top—but she is, after all, playing one of the screen’s first out-and-out female psychopaths: why shouldn’t she let rip? But there’s more to it than that: method in her madness, if you like. Vitally for the film’s success, the extravagance of Osborne’s performance allows her to establish for Ruth Rogen a distinct set of physical mannerisms, which Carole Lombard is then able to reproduce when Roma is taken over by Ruth. Both women do a remarkable job in conveying Ruth’s viciousness, her pleasure in killing. But there is also some subtlety in Lombard’s performance, at least—such as the way in which, as Ruth, she looks around quickly on the unfamiliar yacht in order to get her bearings; or how she has to feel for the light-switch in the cabin, contrasting with her unthinking movement in Ruth’s studio.

For the first half of Supernatural, Roma Courtney is a standard horror-movie heroine in concept and behaviour, the usual “good girl”: we have little reason to expect much of her. But even in these bland establishing scenes, Lombard does well—laughing and crying together as she listens to recordings of John’s voice, for instance. Not she, but the film itself falters in these scenes, giving insufficient weight, not just to Roma’s bereavement, but to her position as bereaved twin, before it starts plunging her into séances.

But once Ruth has taken over Roma, Lombard has something she can get her teeth into—and she demonstrates that despite her talent for, and preference for, comedic roles, she was an excellent dramatic actress as well. As a woman possessed, she creates a fascinating duel-persona: not just Roma-possessed-by-Ruth, but Ruth controlling herself as Roma – most of the time; toying with Bavian as she reveals herself to him, little by little…

Knowing what we do about the production history of Supernatural, the most surprising thing about it may be that none of Carole Lombard’s negativity about the production shows itself in the film; in fact, if you didn’t know better, you’d swear she was enjoying herself playing Ruth Rogen. Perhaps she was imagining having Victor Halperin’s throat in her hands… But whatever Lombard was doing off-camera, onscreen we see nothing but a consummate professional, and a wonderful talent. We may well feel aggrieved that she succeeded in avoiding ever making another horror movie—but we can certainly appreciate what she brought to this one.

Footnote: Please be aware that these images were not taken from the Warners DVD-R. (Though I am now considering an upgrade.)

A little more on this film in WANT!! and Spinning Newspaper Injures Printer.

Want a second opinion of Supernatural? Visit 1000 Misspent Hours – And Counting.

♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦

This review is part of the B-Masters’ examination of the early days of horror cinema.

Can you have an orgy with only 2 people? Or were other people around when Ruth killed her lovers? Maybe she killed them all at once?

In the movies and tv shows, men are always interested in a three (or more) way, but they seem to expect the extra partners to all be women.

LikeLike

Well, “orgy” is a newspaper word, so we might want to take it with a grain of salt.

What I understand them to mean is, that there was drinking and drugs(?) and sex then murder—on three separate occasions, not all at once. 😀

LikeLike

I wonder if Miss Manners has some guidelines on what is involved for a proper orgy. Are 2 people enough if there are plenty of drinks and drugs (Murder optional)? Without the drugs, how many people are required?

This is important information. I’m planning my Memorial Day picnic.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Well, all the best parties are progressive!

LikeLike

Wow, the movie killed off the comic relief? And when it wasn’t really an odious comic relief? There ain’t no justice.

Speaking of which, one wonders what Hollywood would have become without the Production Code. I suppose the backlash was inevitable, given American culture, but its such a shame.

LikeLike

And in that respect, we should remember that the Code was finally enforced as much in response to the social-criticism films made during the Depression, as because of the rising tide of sex and violence.

LikeLiked by 2 people

So, question:

Who actually killed John Courtney? I get that Bavian was trying to blame the lawyer so Roma wouldn’t trust him and leave a clear path to the cash–but it wasn’t actually Hammond, Bavian, or Ruth, right? I assume it also wasn’t a clear accident that would make any accusations of foul play ridiculous, like he was in car accident or had a heart attack.

And what was Bavian planning to do with Grant? He couldn’t very well accuse him as well, and he was too young for the “heart attack” poison thing to be credible. I guess I’m saying that if I was a fake spiritualist I’d try to thin the field a bit and THEN show up with offers of supernatural comfort.

(And if you want a great example of a truly charismatic con man bilking lonely ladies of their fortunes, I love The Amazing Mr. X.)

LikeLike

I read the review again, and there’s nothing to indicate that John Courtney was actually murdered. It may have just all been a con by Bavian.

By the way, who was Grant, anyways? I didn’t see any explanation of who he was. Unless he was by definition Roma’s boyfriend (hey, all women have to have one, or there’s something wrong with them – at least at this time in the movies).

LikeLike

Yes, he’s Roma’s boyfriend.

I can see Bavian conning people into thinking their tragically dead relatives were ACTUALLY MURDERED, scummy as that is.

LikeLike

We do not ever know how John Courtney died, or why Hammond was on the scene. There is no evidence that he was murdered—or that either Ruth or Hammond had anything to do with his death. (The former seems a reviewer’s misapprehension, understandable from the juxtaposition of elements, but unsupported by the film; the latter likewise is almost certainly a lie by Bavian.)

Grant is in love with Roma but has been out of the country on business for some time, so there’s no formal relationship between them when the film opens. He returns just before John dies, and becomes one of the people Roma leans on in her bereavement. I call him Roma’s fiance in the summary just for convenience’s sake, as that’s where they’re heading. His only contribution is to intervene to prevent Ruth / Roma murdering Bavian directly. (And yes, to show that all proper women have a boyfriend.)

LikeLiked by 1 person

Speaking as an information technologist, I contend that possession and murder is a form of communication.

Contagion, yes! You might catch necromanticserialkilleritis! Fortunately the pathogens are very large, and can’t get through closed doors.

LikeLike

Yes, exactly! – the contrast between the enormity of that scene’s implications and its absurdly casual attitude is just dizzying.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This sounds like a must-see, despite its iffyness. (I’ve never seen a Carole Lombard pic.)

LikeLike

It is! And you should at least see To Be Or Not To Be.

LikeLike