“Free! Free at last!”

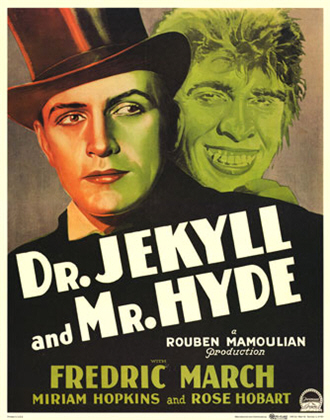

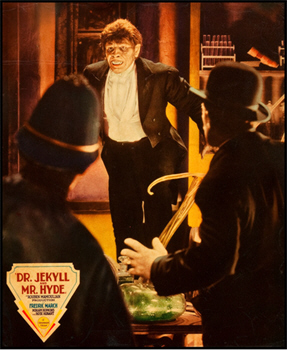

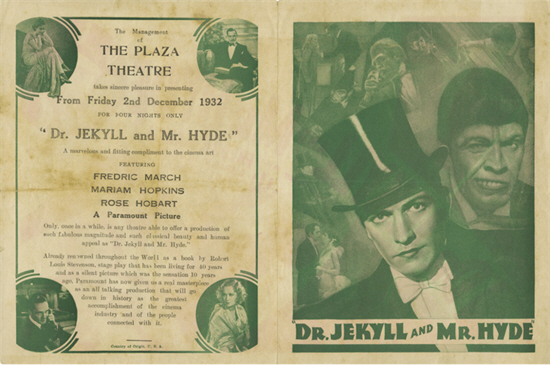

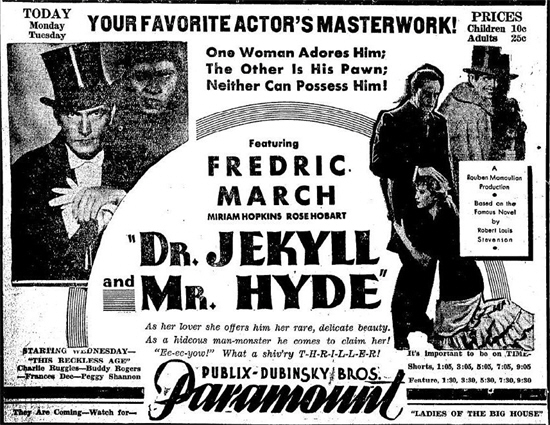

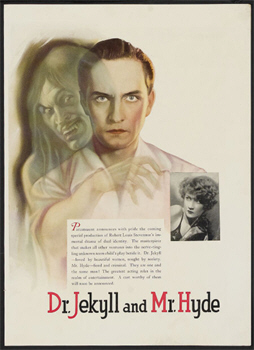

Director: Rouben Mamoulian

Starring: Fredric March, Miriam Hopkins, Rose Hobart, Halliwell Hobbes, Holmes Herbert, Edgar Norton

Screenplay: Samuel Hofferstein and Percy Heath, based upon the novel by Robert Louis Stevenson

Synopsis: Dr Henry Jekyll (Fredric March) lectures at St Simon’s College in London, expounding on his theory that the good and evil in the human soul can be separated by scientific means. His assertion is met with a mixture of fascination, shock, and disapproval. Especially critical is Jekyll’s colleague, Dr John Lanyon (Holmes Herbert), whose strictures Jekyll receives with good humour. Jekyll dismisses Lanyon’s reminder that he is due for a consultation with a duchess, choosing to devote his time to free-ward patients instead; although he promises Lanyon that he will keep his dinner engagement at the home of General Sir Danvers Carew (Halliwell Hobbes) and his daughter, Muriel (Rose Hobart), to whom Jekyll is engaged. Jekyll is late, however. Carew is disapproving, but Muriel defends Jekyll staunchly, insisting that she is proud of him for his dedication to helping the poor. When Jekyll does arrive, he induces Muriel to slip away to the garden with him, where they kiss passionately. Jekyll persuades Muriel to agree to an immediate marriage, but she adds that she must obey her father, who rejects Jekyll’s plea for an earlier date. As Jekyll grows more insistent, the General takes offense, finally telling him that his impatience is indecent. An angry Jekyll, muttering imprecations against the General, leaves with Lanyon. As the two men argue their opposing philosophies, they are interrupted by the sound of a violent quarrel. Jekyll rushes forward to the rescue of a young woman, Ivy Pierson (Miriam Hopkins), chasing away the man who was attacking her. Jekyll carries Ivy up to her rooms where, misunderstanding his ministrations, she begins to undress, then throws her arms about him and kisses him—just as Lanyon walks in, looking for Jekyll. Lanyon is shocked, but Jekyll laughs the incident off, dismissing it as “an impulse”, and insisting that while men can and must control their actions, impulses are another matter. He adds that only by ridding himself of his baser nature altogether can a man be truly clean in thought and action. Throwing himself into his research, Jekyll succeeds in creating a chemical draught that, he believes, is capable of severing the good and the evil bound together in the soul. Writing a precautionary farewell letter to Muriel, Jekyll tests his invention on himself, undergoing an agonising transformation as a result. When he gazes at himself in the mirror afterwards, Jekyll sees not a Victorian gentleman, but a frightening, bestial figure… Poole (Edgar Norton), Jekyll’s butler, hearing a strange voice, pounds worriedly upon the locked laboratory door. It is opened by a flustered Jekyll, who tells Poole that there was someone else in the room – a friend of his, a Mr Hyde – who left by the back door. Jekyll again pleads with Muriel to marry him at once, trying to persuade her to elope if they cannot secure her father’s consent. Muriel will not agree to this, however, and tells Jekyll reluctantly that she and her father will be leaving London for an indefinite period. Seeing her fiancé utterly downcast, Muriel asks with gentle reproach if he does not love her enough to wait just a little longer? Jekyll replies that he can and will wait—but as time passes, his frustration grows; until one fatal night when, learning that Muriel will not return for another month still, Jekyll again prepares his mysterious draught…

Comments: In the silent era, most American horror movies were rather nervous efforts, more likely than not to have their supernatural elements explained away, and to be leavened still further by the insertion of the most painful kind of “comedy relief”. As far as true screen horror went, apart from Lon Chaney’s macabre but real-world-based offerings the Germans had it nearly all their own way; a situation that would not change until sound cinema was fully three years old.

The year 1931 would prove to be a landmark in the history of screen horror, with the eternally cash-starved Universal Studios taking its financial life in its hands by producing a version of Dracula – and then, emboldened by the public’s enthusiastic reception of their first venture, by defying the critics, both cinematic and social, and following their first experiment with a filming of Frankenstein. Horror on the American screen was never the same again.

However, although their historical importance cannot possibly be overestimated, the fact remains that as motion pictures, both Dracula and Frankenstein are severely flawed; both require the modern viewer to approach them armed with historical perspective and a large measure of good will in order to appreciate them.

Most unexpectedly, it would not be Universal, “the House Of Horrors”, at all, but Paramount Studios, an organisation best known for glossy, star-heavy productions, that would take things to the next level, producing a film as horrifying as it is dramatically compelling, and daring both thematically and visually: Rouben Mamoulian’s version of Dr Jekyll And Mr Hyde, released on New Year’s Eve, 1931.

Although many film-makers struggled painfully with the transition from silent cinema to talking pictures, the Armenian-Russian émigré Rouben Mamoulian was not of their number. After beginning as a stage director in London before securing a job teaching opera and theatre in New York, Mamoulian soon graduated to directing on Broadway. By 1929, when he made the move to Hollywood, no-one was more an advocate of dialogue, or better understood the power, not just of the spoken word, but of music and of sound effects, too. While other directors of talent and vision seemed almost paralysed by the need to work to a microphone, Mamoulian not only took the new technology in his stride, but proceeded to demonstrate to his bemused contemporaries how its seeming limitations could be overcome.

The result of this was Applause, a frank melodrama of a mother with a past dealing with her innocent daughter, which stunned the film community by successfully using two-track sound, in order to present simultaneously the mother’s risqué stage songs and the daughter’s prayers. The film was likewise remarkable for its visual extravagance and its use of symbolism; for the fluidity of its camerawork, another landmark in an era when the need to centre on the microphone nailed some directors to the spot; and for its location shooting.

Mamoulian continued to experiment with his next project, the taut crime drama City Streets, where the mobility of the cinematography was matched by some masterful use of light and shadow. The film also boasts the first screen flashback of the sound era, a scene accompanied by more of what were rapidly becoming Mamoulian’s trademark visual flourishes.

Not everyone approved of Rouben Mamoulian’s flamboyant style—but everyone noticed it. It was even startling enough to win over the Paramount executives, who operated their studio on the premise that stars were everything, and the director, very much a secondary consideration; though paradoxically this actor-fixation had the side-effect of granting Paramount directors unusual freedom. Violating their own conventions, studio heads Adolph Zukor and B.P. Schulberg reward Mamoulian’s ground-breaking efforts with his choice of project.

Paramount already owned the rights to the film version of Dr Jekyll And Mr Hyde, having acquired them when the studio absorbed Jesse L. Lasky’s Famous Players Company during the late twenties, and a re-make of the hugely successful 1920 production had been planned for some time. However, the venture foundered when John Barrymore rejected Adolph Zukor’s suggestion that he reprise his dual starring roles. Consequently, Zukor was delighted when Mamoulian chose to revive the project—only to throw up his hands in disbelief at the director’s casting choices. His mind on Hyde, Zukor offered Mamoulian screen heavy after screen heavy; Mamoulian rejected them all, arguing that he wanted someone who could play Jekyll—and insisting upon the signing of Fredric March, at the time known best as a pretty-boy secondary lead and a light comedian.

March’s casting in the dual roles of Jekyll and Hyde was one attended by a good deal of irony. When John Barrymore had briefly stepped aside from his stage career to appear on film as horror’s most famous split personality, he had been motivated not just by the acting challenge involved, but by a desire to break away from too many bloodless roles that required little more of him than to stand there and be handsome.

This was a fate that Fredric March was destined to suffer also. Although March had played bit parts in film all the way through the twenties, his real success was as a stage actor. His permanent move to motion pictures came as a result, oddly enough, of the rave reviews that he won with his performance in The Royal Family Of Broadway, a comedy loosely based upon the Barrymores themselves, in which March was the play’s “John”, Tony Cavendish; his first major film success would be a reprise of his stage triumph.

However, the praise March won in the early phase of his new career wasn’t quite what he wanted: when the critics started calling him “the new John Barrymore”, they weren’t referring to his acting abilities; they were talking about his profile. Even as early as 1931, Fredric March was sick of it, and looking for a way of proving that he was more than just a pretty face. Rouben Mamoulian’s offer of Dr Jekyll And Mr Hyde was a professional godsend.

Mamoulian’s vision of his film also led him to shape the direction of the screenplay. Few stories have been filmed as often as Robert Louis Stevenson’s classic tale, but similarly, few stories have undergone such a clear cinematic evolution. The tale was filmed and filmed again during the silent era, with the first versions based upon the stage adaptations that had proliferated in the wake of Stevenson’s success, and with each version building upon the ones that went before it, taking elements introduced by previous writers and directors and turning them to their own purposes. It can be a surprising experience to go back now and read Stevenson’s story, and discover just how much we think we know of it is actually the invention of the movies.

Stevenson’s Jekyll is, when all is said and done, rather a pathetic figure, a middle-aged man so terrified of losing face before his friends if he indulges his unacceptable desires openly that he is driven to release his alter-ego, Hyde, so that he can indulge them in secret. Significantly, along with Jekyll’s final confession comes his realisation that, had he experimented with his dual nature for less ignominious reasons, then Hyde might very well have been a power for good.

Not surprisingly, this weak and somewhat pitiful Jekyll has rarely made it onto our motion picture screens. Perhaps the Jekyll of the Terence Fisher-directed, Wolf Mankowitz-scripted The Two Faces Of Dr Jekyll comes closest—a version that, amusingly, is invariably tagged “revisionist”. The earliest version of Dr Jekyll And Mr Hyde of any real substance, that directed by Herbert Brenon in 1913, invented a Jekyll about as far from Stevenson’s own conception of the character as it could be: a saintly Jekyll devoted to the poor and meaning only good; his experiments to “release his evil side” are unexplained and, indeed, inexplicable.

Nevertheless, this concept of “saintly Dr Jekyll” took root, reappearing still more strongly in the version directed by John S. Robertson, and starring John Barrymore, whose Jekyll is an innocent abroad, a man almost unaware of his own dark side, until he is deliberately introduced to it by a Mephistophelean acquaintance. Rouben Mamoulian’s idea of Jekyll was certainly drawn from the Barrymore version, but conceived in still more tragic terms: his version would be the story of a soaring soul, a man aspiring to greatness and fighting against his baser nature, but ultimately dragged to earth and destroyed by his own darkest impulses.

The second legacy of the Barrymore version and its screenwriter Clara Beranger was the decision to illustrate the central character’s duality by placing him between a “good girl” and a “bad girl”. This, too, Mamoulian kept but significantly expanded, expressing both Jekyll and Hyde in terms startling for their sexual frankness.

The 1931 version of Dr Jekyll And Mr Hyde was, of course, produced in the middle of what is conventionally called the “pre-Code era”, although that is actually something of a misnomer. The Motion Picture Production Code had been introduced in the late twenties in response to public outcry against the so-called immorality of the movies—and more to the point, the perceived immorality of those making the movies. In theory the Code restricted the inclusion in films of extreme or immoral material, but until 1934, when it was belatedly backed up by the big stick of the absolute requirement for an official “Seal Of Approval” before a film could be released, the Code was a paper tiger.

For the most part, as long as they could secure the co-operation of their studio heads, film-makers could and did ignore it, a state of affairs that produced a rich crop of films that dealt forthrightly with soon-to-be-taboo subject matters and themes including explicit violence, unpunished crime, drug and alcohol abuse, and above all, sex.

This is not to say that films of this era used explicit language, or contained graphic sex scenes (although you could get away with a quick flash of nudity, as Mamoulian does here). The point is not just that these films called a spade a spade; it is, rather, that they were not compelled, to their own detriment, and as later films were, to call a spade a wheelbarrow. While not necessarily promoting sex out of marriage, films of this era simply accepted the fact that it existed, and felt no particular need to punish those who indulged—unless it was dramatically valid to do so.

Moreover, they accepted, too, that women as well as men felt sexual desire, and that their doing so by no means made them “bad” – or at least not any worse, morally speaking, than their male counterparts. There is a maturity and an honesty about the films of this period that, in my opinion, has hardly been matched since.

The brilliance of the Rouben Mamoulian’s interpretation of Dr Jekyll And My Hyde lies not merely in its frankness, but in the way that it takes full advantage of the sexual freedom of the pre-Code era specifically in order to tell a tale of sexual repression and its potentially dangerous consequences. As we have already seen, there are numerous ironies attached to this version of the tale. The crowning one, surely, is that this protest against repression would, in the years following its release, become itself the victim of repression, being censored and re-censored until most of its true meaning had been pruned away—and until one of its leading ladies was hardly in the film at all…

(And then the final indignity: that when MGM were preparing their own version of Dr Jekyll And Mr Hyde, they first bought up the prints of Paramount’s version and buried them, so that no-one could make comparisons. It was the late sixties before Rouben Mamoulian’s film saw the light of day again, and 1989 before all the censored material was restored.)

Dr Jekyll And Mr Hyde wastes no time letting us know Mamoulian’s conception of Jekyll. The film opens with a two and a half minute sequence shot almost entirely subjectively, giving us events through Jekyll’s eyes: his organ-playing (Bach, of course), his journey to the medical school where he is due to speak, his gaze around the full-to-overflowing lecture hall. This prepares us to spend part of the story walking in Jekyll’s shoes, feeling his eventual sufferings; but the purpose of this audacious opening sequence goes beyond that. The immediate sense here is of Jekyll as egoist.

Of course, there is good ego as well as bad, and we get both from Jekyll: the bad ego that leads him to expect people to bow down as he approaches; to expect an overflowing lecture hall, and an audience hanging on his every word, and that enjoys the sensation that his unorthodox theories create; but there is also the good ego, the self-assuredness with which Jekyll unhesitatingly sacrifices the potential social advantage of attending a duchess, dismissing her with a frank but tactless diagnosis of “bilious” and a recommendation of castor oil, in order to devote his time to his charity patients in the free ward.

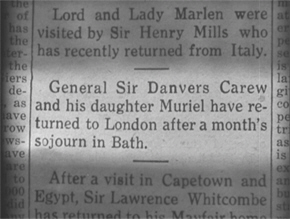

Jekyll’s commitments there bring him into conflict with his social equals, as he gives in to the pleadings of an elderly patient, and stays to operate on her himself instead of handing her case over to “a house surgeon” (a phrase that hardly inspires less horror in the viewer than it does the patient), as his colleague, Dr Lanyon, rather callously advises. Jekyll’s dedication also leads him to miss dinner at the house of Brigadier-General Sir Danvers Carew, who is less than pleased with the excuse offered for Jekyll by Lanyon, fuming that it past time that Jekyll “came down to earth”, and – presumably – reserved his professional expertise for bilious (and wealthy) duchesses.

The subjective photography of the opening scene is supplemented by the first of this film’s numerous mirror scenes, which Mamoulian uses brilliantly throughout to illustrate the theme of duality; a theme further underscored via a more experimental visual technique, a split-screen wipe that serves to highlight the opposing forces and impulses that operate both within and upon Jekyll. The initial contrast drawn is between Jekyll’s patient, drawing confidence by clutching her doctor’s hand, and Miss Muriel Carew, Jekyll’s fiancé, first seen fussing over a lack of almond cakes for her dinner party.

This introduction is rather unjust to Muriel. For one thing, the almond cakes are intended as a treat for Jekyll himself; for another, Muriel is considerably more than just a social butterfly, defending her man staunchly against her father’s strictures and declaring her love and pride in him openly. “Father would be furious!” she comments after Jekyll, arriving belatedly, urges her to slip away into the garden with him; but she goes willingly enough, and is soon an equal participant in some passionate kissing; she is barely even embarrassed when the butler, coughing apologetically, subsequently catches them at it. When Jekyll pleads with Muriel to agree to an early marriage, she agrees without hesitation or reluctance either real or assumed.

But forthright as she is about her love for Jekyll and her desire for their marriage, Muriel is also a dutiful daughter, and will take no step without her father’s consent.

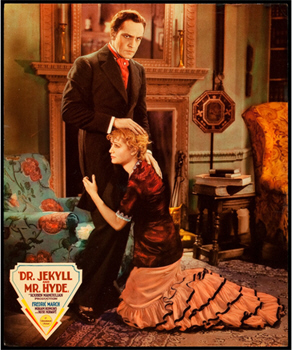

I’ve been guilty in the past of a tendency to undervalue Rose Hobart’s contribution to this film. Heaven knows, playing the “good girl” in a story like this is generally the most thankless of tasks, not least because the “bad girl” is, whatever the moralists try to tell us, usually more attractive and always more interesting. (And the “bad girl” here is certainly something to behold.) Increasing distance has done nothing to help her character in this respect: it is a little too easy for modern viewers, nearly ninety years after this film was made and a hundred and forty-odd after it was set, to grow impatient and unsympathetic with Muriel and her refusal to flout her father’s wishes; but with the right kind of perspective we can see that Hobart really makes something of the role.

Although she comes most into her own late in the film, when Jekyll is at the height of his tragedy, even in these early scenes Hobart gives us a Muriel we can like, showing us that she has character and backbone enough to be a fitting mate for Jekyll, and making us feel for her as she undertakes the impossible task of trying to reconcile her duties to the two men in her life.

And it is impossible. As played by veteran character actor Halliwell Hobbes, General Carew is an acute portrait of a petty domestic tyrant. He’s not a bad man – he’s not an uncaring man – he’s certainly not a violent man – but he is a man of boundless selfishness, one who expects his most trivial whims to be humoured without question; a man quite capable, and in all sincerity, of making a prime virtue out of the fact that in forty years, he’s never once been late for dinner. That for most of those forty years dinner has been arranged to suit his convenience never occurs to him, of course.

In other circumstances, General Carew might be harmless, even rather funny; but in Rouben Mamoulian’s vision of this story, he is the enemy, the personification of every convention and shibboleth that helped win the Victorian era its reputation for repression—and for hypocrisy.

In his position as Muriel’s father, Carew holds the whip-hand over Jekyll, and wields it without compunction. If Jekyll, all impatience and disregard for social niceties, is the worst imaginable son-in-law for the General, then the General, with his platitudes and his pomposity and his small-mindedness, is a father-in-law to drive Jekyll to the edge of madness…and beyond.

While I believe that Dr Jekyll And Mr Hyde is a great film, it is certainly not without its weaknesses. Although Rouben Mamoulian’s artistic daring and visual prowess put him ahead of most of his contemporaries on a technical level, there were other problems associated with the silent-to-sound transition that were less satisfactorily dealt with. For one, it took time before the actors of this period, accustomed as they were to the conventions of the silent cinema, and confronted all of a sudden by the threat of the microphone, were able to relax into a more natural approach to their craft.

The other significant challenge of this era came at the level of the script. With the focus so much upon the technical challenges of the early sound film, it is easy to overlook the fact that all of a sudden, films needed writers; not creators of inter-titles, but authors of screenplays. This, too, was an art developed only with time and practice. Hollywood did its best in this respect, hiring novelists and playwrights, those accustomed to the written word; but the fact remains that a novel or a play is not a screenplay: the result, very often, was dialogue either too stilted or too florid – either way, unnatural – and some very uncomfortable actors.

Dr Jekyll And Mr Hyde certainly reflects both of these issues, although it is necessary to distinguish between the artefacts of the time of the film’s production, and conscious choices made by Rouben Mamoulian, some of which may seem just as anachronistic to modern sensibilities. It is difficult to decide, for example, whether the stiffness of the supporting cast and their occasionally wooden delivery is the result of the comparative neglect of these characters as Mamoulian pursued his vision of Jekyll and Hyde, or whether they are that way intentionally, to help convey the stultifying social world that Henry Jekyll finds increasingly intolerable.

As for the verbal extravagance of Fredric March’s Jekyll, however, there can be no doubt that this was entirely deliberate: the character is very much delineated through his dialogue and the way he delivers it. Jekyll’s addiction to purple prose is both significant and understandable. In an oppressive society full of restrictions, Jekyll uses language as an outlet, channelling his energies, including his sexual energies, into his speech.

But as Jekyll will soon learn, the society against which he is rebelling has a language of its own, and uses it to similar if completely contrasting ends. When the enemy that is Society itself stands against Henry Jekyll, he will find it clad in an impenetrable armour comprised entirely of words.

Jekyll stays behind after the party, pressing General Carew to consent to an immediate marriage. We learn during this exchange that Jekyll and Muriel have already been engaged for two months, with no near end in sight. Victorian engagements often were a lengthy affair, of course, although amongst the upper-class this was rarely for the same reason found amongst the middle- and lower-classes, that is, the need to reach a certain plateau of financial security first. Aristocratic marriages, in contrast, were generally delayed by the lawyers sorting out the money matters; by how long it took the bride to get her trousseau together; and by the need to wait until the weather was suitable wherever was considered the fashionable honeymoon destination du jour.

We don’t hear anything about money here (neither Jekyll nor Carew is exactly struggling, though); Muriel doesn’t strike us as the kind to worry overmuch over her trousseau; and as for Jekyll, he is never more likeable than when suggesting a honeymoon spent in Devon, of all unfashionable places, where he and Muriel are to live upon, “Love, and strawberries, and moonlight”. None of these issues are the reason for the delay, however, which turns out to be due to General Carew having a bee in his bonnet, and insisting that the couple be married on the same day he was, a full eight months away. Jekyll, understandably, has difficulty believing that Carew is quite serious about this, and says so a little too bluntly –“I can’t regard that as a serious objection!” – and immediately the General takes offense.

The verbal battle between Jekyll and Carew, and the argument that follows between Jekyll and Lanyon, comprise one of this film’s most crucial sequences. Jekyll presses the issue, becoming more and more agitated; and as he does so, the primary motivation for his urgency, namely, the intensity of his sexual desire for Muriel, is progressively revealed—which in turn causes the General to take deeper and deeper offense, and grow more and more obstinate.

(In fairness to the General, it’s difficult to imagine any father responding well to this particular line of argument, however obliquely it is phrased.)

The most critical aspect of this scene, however, is the language in which it is couched, with the reiteration of words and phrases that, quite literally, will come back to haunt Henry Jekyll: “It isn’t done – it isn’t done!” protests the General. As Jekyll concedes his “impatience in love”, Carew, praising his own “sturdy temperament”, recoils: “Do you hear him? It’s positively indecent!” – and continues to reject Jekyll’s petition, insisting upon, “A decent observance.” From the latter we infer that there was an unspecified minimum period that engagements were meant to last, presumably to convince any interested parties that the couple in question were not, in fact, “indecently” eager—and nor was their union Victorian England’s equivalent of a shotgun wedding.

Jekyll, reluctantly, gives it up, and departs with Lanyon. That bastion of society is quite on the General’s side, particularly in respect to what both men view as Jekyll’s “eccentricity”. There is no real suggestion in this film that any feeling for Muriel inspires Lanyon’s disapproval of Jekyll; he disapproves simply because he disapproves; and as they walk away, Lanyon observes, “I’m afraid you offended the General.”

“Offended him?” fumes Jekyll. “It’s a pity I didn’t strangle the old walrus!”

Lanyon then offers up the rather dismal hope that “the responsibilities of marriage” will “sober” Jekyll. “I’m not marrying to be sober – I’m marrying to be drunk!” retorts Jekyll. This conflicting vision of the marital state – Jekyll’s view of it as an adventure, as fun, is particularly attractive – then segues into a still more conflicting view of Jekyll’s experimental work, during which Lanyon insists that, “There are bounds beyond which one must not go.”

“It isn’t done, I suppose?” returns Jekyll sarcastically. “I tell you, there are no bounds.”

As Lanyon continues to censure him for his fascination with “short-cuts and by-ways”, Jekyll cries, “It is in the by-ways that the secrets and wonders lie – in science and in life!”

And at this rather critical juncture, Jekyll is interrupted by the sound of a woman’s scream…

For those unacquainted with this era in film-making, Miriam Hopkins’ performance in Dr Jekyll And Mr Hyde can come as a staggering revelation. Like Fredric March, she had had success upon the stage, but in 1931 was only just establishing herself in film; and like March again, she was hand-picked by Rouben Mamoulian for this film. He could hardly have made a better or a braver choice.

There is a tendency to talk about the eventual enforcement of the Production Code in terms of people like Mae West and Jean Harlow, but I’m not sure anyone was more adversely affected by it than Miriam Hopkins. Hopkins was a risk-taker, and the greater the challenge, the better her performance, as can be seen in films as disparate as The Story Of Temple Drake, Paramount’s version of William Faulkner’s Sanctuary (as far as they were allowed to film it: there were limits, even in the pre-Code era), and the daring Ernst Lubitsch-directed comedies Trouble In Paradise, in which she plays a jewel thief for whom robbing and being robbed is a sexual turn-on, and Design For Living, which finds her in a ménage à trois with Fredric March and Gary Cooper.

Hopkins was notoriously difficult to work with – she was a temperamental drama queen off-screen, and a shameless scene-stealer on-screen – but when she hit the mark, the results were worth all the trouble she caused. (Mamoulian must have thought so: he worked with her again on 1935’s Becky Sharp.) However, the coming of Production Code put a stop to Miriam Hopkins doing what she did best; and although she gave some effective character performances later in her career, she never matched her work of the pre-Code era.

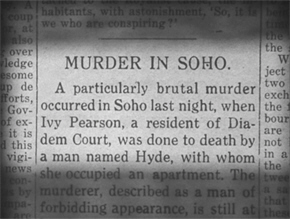

Dr Jekyll And Mr Hyde makes no bones about Ivy Pierson being a prostitute, although the word itself is never spoken. If we did have any doubt, the phrase used by Ivy’s neighbour to describe the man from whom Jekyll rescues her is enough to settle it: he is referred to, not as, “Ivy Pierson’s caller”, but as, “One of Ivy Pierson’s callers”. (The original script actually used the word “customer”, but they didn’t get away with going that far.) When Jekyll impulsively intervenes, he chases off this “caller” – presumably a john disputing the bill – and carries Ivy, who has been knocked to the ground, up to her rooms.

Ivy is too taken up at first with making verbal threats against her assailant to pay much attention to her rescuer, but when, having been deposited up her bed, she looks up and sees the unmistakable toff who has come to her assistance, her expression says as clearly as if she had spoken the word out loud—jackpot. Instantly, she makes a pass at him.

The scene between Jekyll and Ivy is one of the most frankly erotic even of this emancipated time. It is also remarkably free of any hint of either salaciousness or embarrassment, both of which would too often infuse sexually charged scenes in later years; and, most significantly, of any sense of apology, or the need for one. Also striking in its absence is any condemnation of Ivy. This film never does what so many, many others do, tries to shift the blame for its hero’s fall onto a woman. Ivy is tempting and Jekyll is tempted, but this is not considered “her fault”; it isn’t even held against her that she is what she is; and nor, when tragedy inevitably strikes, is there a suggestion that Ivy deserves what she gets. She does not—and that is the real tragedy.

The thing that lingers most about Ivy, at least the Ivy of this point in the story, is the unabashedly cheerful way she goes about her business—although there is more than a hint here that this interlude isn’t entirely business, but rather Ivy trying for a brief taste of life on the other side of the tracks; although, had the matter gone to what we might consider its logical conclusion, Jekyll certainly would have offered money, and Ivy certainly would have accepted it. She isn’t ashamed of her actions—and nor is Jekyll about enjoying the show she puts on for him, stripping off under the pretence of getting ready to recover from her “ordeal” by “resting”, before slipping expectantly under the covers. When Jekyll ventures a little too close to the bed, overtly to offer “medical advice”, Ivy strikes, drawing him down into a passionate embrace.

This is where and how the horrified Lanyon walks in to find him, being instantly provoked to an outraged, “Oh…I say!” – which Jekyll finds just as comical as we do. And whatever we make of Jekyll’s behaviour during this scene, it must be pointed out that it is Dr Lanyon, that upright gentleman, who is guilty here of what can only be described as some very vulgar ogling.

Jekyll detaches himself from the disappointed Ivy and prepares to leave; but Ivy doesn’t give up without one more effort. Perched provocatively on the edge of the bed, the covers not quite covering, and with one lovely garter-ringed leg swinging alluringly back and forth, she begs Jekyll to return to her, dismissing his insistence that he can’t with a laughing, “Oh, yes, you can” – and following him on his way with an urgent whisper, “Come back soon…soon…”

Another of Mamoulian’s visual tactics is to fade from scene to scene, holding a critical shot so that it overlays and colours the one to follow. He does this here, with Ivy’s leg and her seductive whisper bleeding into the inevitable clash between Jekyll and Lanyon—in which, also inevitably, the words reappear. “I thought your conduct quite disgusting!” is Lanyon’s opening volley. At first Jekyll is prepared to laugh off Lanyon’s criticisms, until Lanyon accuses him of forgetting his engagement, which wipes the smile from his face. “Forgotten it? Can a man dying of thirst forget water? And do you know what would happen to that thirst if it were denied water—?”

And Lanyon, just as General Carew did, recoils. “If I understand you correctly—you sound almost indecent!”

Even though its screenwriters were compelled to be circumspect in their choice of terms, Dr Jekyll And Mr Hyde could hardly be more explicit about the sexual motivations of Jekyll’s actions. Where it separates itself from the pack, however, is in its tacit support of his attitude. To this film’s infinite credit, it finds nothing dirty in sex itself, nothing to criticise in Jekyll’s self-awareness—and certainly not in his longing to express his desire for Muriel as well as his love, both of which he rightly classes amongst his “clean, decent” impulses.

Moreover, both the film and Jekyll are only too well aware of the danger that threatens, should a natural, and for that matter lawful, sexual desire be thwarted and denied by social convention. Jekyll here voices his yearning to be “clean”, not only in his actions, which he claims can be controlled whatever a man’s impulses, but also in his “innermost thoughts and desires”. It is to this end, he insists, that his research is devoted.

One of the real joys of Dr Jekyll And Mr Hyde is its production design, in which Rouben Mamoulian collaborated with Hans Dreier. Some people find the director’s films “over-stuffed” – think Josef von Sternberg, but not quite that extreme – but Mamoulian knew what he was doing. The lush romanticism of the garden scene between Jekyll and Muriel, and the cavernous luxuriousness of General Carew’s and Jekyll’s own houses, are starkly contrasted with Ivy Pierson’s squalid Soho existence. Mamoulian was also very much addicted to the use of symbolic objets d’art, and there is no shortage of them in this film, particularly during what will prove to be its emotional climax. (Watch out in particular for the sickly ironic cupids on the bed-posts in Ivy’s “love-nest”.)

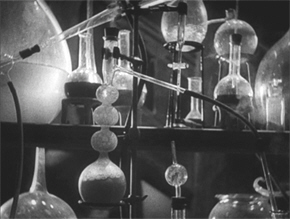

But the high point of Dr Jekyll And Mr Hyde (at least, it is for me) is our first good look around Jekyll’s home laboratory, housed in a separate facility from his house and connected to it by a walkway. We are so used today to “science”, particularly “mad science”, on film that it can be hard to remember that there was a time when there really was no such thing; when the public had little idea of what might be found inside a research laboratory, be it real or entirely imaginary.

If Frankenstein and its electrical equipment anchored in the imagination as one definitive kind of movie laboratory, its main challenger is found here: Jekyll’s lair is a masterpiece of the cinematic imagination, a jungle of flasks and stands and test tubes and crucibles, with a perpetual fire fore-grounded, on which sits a lidded pot, in constant threat of boiling over (what was I saying about Mamoulian and his symbolism?); and although this film is in glorious black and white, we do not doubt, as the camera pans around, that each one of those Mysterious Fluids filling every one of those Conical Flasks is, indeed…Coloured.

Significantly, while Jekyll toils away on his quest to “separate our two natures”, we return to the use of the subjective camera. At last comes the time when Jekyll contemplates the fatal potion. He hesitates, first locking the laboratory door, then casting a wry smile at a skeleton hanging in one corner of the room—and then, his smile fading, he writes a farewell letter to Muriel, in which, along with a profession of eternal love, he assures her that, If I die, it will be in the cause of science.

(I’m sure that will be a great consolation to her.)

And then he swallows the draught…

We watch as Jekyll clutches his throat, his face distorting as strange, unearthly noises ring out – and then the laboratory begins to fade before Jekyll’s, and our, eyes, dancing and spinning as it fades into an image of Muriel, as Jekyll urges her to marry him – and then into one of Ivy. We see faces, hear voices: Jekyll’s own, expressing his anger – “—Pity I didn’t strangle him!—” – and his frustration – “Can a man dying of thirst forget water?” And then Carew, and Lanyon, and those words, those words: “It isn’t done! It isn’t done! Positively indecent! Disgusting! Disgusting!” A final cry comes from Lanyon – “You’re mad!” – as the image fades once again to a picture of Ivy, and of her bare leg swinging back and forth, back and forth, as she whispers, “Come back…come back…come back…” It is upon this that the sequence concludes.

By any standard, in any era, this first transformation is an extraordinary piece of the film-maker’s art, a dazzling combination of cinema techniques, and near limitless in its implications. Mamoulian would later reveal how some of its effects were achieved, telling tales of an unfortunate, under-sized focus-puller, strapped to the top of the camera as it was spun around and around; and of the sound effects, famously achieved by recording the striking of a gong and playing it backwards, in combination with various drumbeats and the sound of Mamoulian’s own rapid heartbeats, recorded after he ran up and down a flight of stairs.

And this subjective footage is followed by the revelation of another man’s art, as we are given our first glimpse of—Hyde…

One of the most critical issues to be dealt with in any film version of Dr Jekyll And Mr Hyde is, of course, the design of Hyde. Robert Louis Stevenson himself took full advantage of the freedom of the printed word to create an indescribable Hyde, a man that had nothing overtly wrong with him to look at, yet induced in everyone who saw him a feeling of uncontrollable revulsion. T

here are also descriptions of Hyde as “small”, “pale” and “dwarfish” – in contrast to the bluff and hearty middle-aged gentleman that is the Jekyll of the novel: the sense is of Hyde as a diminished version of Jekyll. A Hyde like this is well-nigh unfilmable, and most directors don’t even try (and that’s assuming they read the novel in the first place).

In this respect, the Barrymore version of Dr Jekyll And Mr Hyde remains unique, giving us an arachnid-like Hyde. The other three silent versions settled upon a simian Hyde—and this, too, was finally Rouben Mamoulian’s choice, albeit in an infinitely more sophisticated manner. Clearly, Mamoulian was reaching for a primitive Hyde, something bestial and devolved; Neanderthal.

As with the transformation scene itself, the creation of Hyde was achieved through a combination of effects, firstly the use of special coloured filters to bring about the distortion of Fredric March’s classically handsome features. This technique was a development of one pioneered in the silent version of Ben-Hur, also photographed by Karl Struss, and at the time it represented the very pinnacle of the special effects man’s art: March’s on-screen transformation drew gasps of disbelief whenever the film was shown. Meanwhile, the full-face makeup and false teeth that give us Hyde in the flesh were the design of Wally Westmore, of the very famous family still active in a similar professional capacity today.

It is a commonplace that actors are supposed to suffer for their art. Just the same, few of them have ever suffered as Fredric March did here. With latex mask technology still in its infancy, the special effects men had worked out how to get the makeup on, but were not quite so certain about how to proceed from there. Throughout Dr Jekyll And Mr Hyde, we see a series of different Hydes, who grows uglier and more animal-like with each transformation. The final and most inhuman Hyde was achieved via a mask attached with liquid rubber directly to Fredric March’s face—and in removing it, as Rose Hobart, a horrified witness, later recounted, the special effects men, “Took most of Freddie’s face off, too.”

March spent three weeks in hospital, recovering, and was considered extraordinarily lucky not to have been scarred for life. A shared Academy Award seems insufficient recompense; perhaps March found his subsequent pick of roles more so. Remarkably, the actor bore no grudge over his experience: when accepting his Oscar, he thanked Wally Westmore and gave much of the credit to his work.

It is difficult to know how far, if at all, Rouben Mamoulian drew upon Stevenson’s novel in his creation of this film, although the influence of the Robertson-Barrymore version is clear enough. However, whether by accident or design, in the timing and above all in the staging of Jekyll’s first transformation, this film finds itself very close to the moral of Stevenson’s story.

Jekyll undertakes his experiment not (so we are told) as a scientist should, coolly and intellectually, in a state of detachment, or even with his higher nature in control, but in the grip of emotional turmoil, seeking escape from his own darkest impulses. That he should consequently fall victim to those very impulses is almost inevitable.

This is, however, the point at which all versions of Dr Jekyll And Mr Hyde founder: what, exactly, does Jekyll expect to happen? The screenplay is too busy being figurative to give us any clear indication. By separating the good and the evil in the human soul, Jekyll declares in his opening lecture, the good might be free to “scale heights”, while evil could “fulfil itself, and trouble us no more” – although how evil is to “fulfil itself” is left to our imaginations. Does Jekyll expect his potion literally to divide him, to produce simultaneously a Good Jekyll and an Evil Jekyll? Does he suppose that his evil side with commit a few dark acts and then somehow cease to be? Or does he in fact think the potion will simply…remove the evil from his soul, leaving him his higher self?

It is impossible even to hazard a guess. The only thing we can be certain of is that Jekyll’s ego once again holds sway here. Although aware of his own “unclean” impulses, it never crosses Jekyll’s mind that his good side isn’t infinitely the stronger; it never occurs to him that his evil side, once unleashed, might be entirely beyond his power to control. But the magnitude of what Jekyll has done is clear to the viewer as soon as a delighted Hyde gazes at himself in the mirror; his immediate cry, his declaration of war, if you will – “Free! Free at last!” – is, in its full implication, one of the most frightening moments in all of thirties horror.

An interruption from Poole, Jekyll’s loyal butler, brings this initial transformation to an end: it is Jekyll himself, flustered and breathless, who finally answers Poole’s increasingly panicked knocking, hurriedly explaining that there was someone else there, a friend of his – “a Mr Hyde” – who left by the back door. Poole gone, Jekyll returns to his mirror, where so short a time ago, a stranger stared back at him…

Jekyll’s next move, tellingly, is once again to beg Muriel to marry him at once, to elope with him if her father still will not consent; and in his extreme agitation we see a reflection of his glimpse into the abyss. As it turns out, things are even worse than Jekyll anticipated: Muriel must reveal that her father, presumably in response to Jekyll’s “indecent” impatience, is taking her away from London.

It is difficult to know whether Muriel recognises the physical, as well as the emotional need behind Jekyll’s pleading, or what she herself is feeling: she is, after all, a good Victorian girl. Muriel is torn but adamant, and eventually a little hurt at what seems to her Jekyll’s refusal to see things from her perspective. “Don’t you love me enough—to wait a little while?” she asks with a hint of reproach.

“Oh, I’ll wait,” responds Jekyll helplessly, almost despairingly, “I’ll wait…”

And wait he does, until the day when a letter from Muriel reveals that she and her father will be away yet another month.

In response to his master’s anger and frustration, Poole offers the suggestion that Jekyll “amuse himself” – “London offers many amusements to a gentleman like you, sir!” “But gentlemen like me,” responds Jekyll sardonically, “daren’t take advantage of them.” With Poole’s departure, Jekyll begins to pace…to grimace…to bite hard upon his pipe-stem…to tap his foot…to rap the knuckles of his hand, the hand still clutching Muriel’s letter, against a table….and finally to take a terrible and decisive step, as that eternally boiling pot at long last boils over…

Before long, Hyde is exchanging Jekyll’s smoking jacket for formal evening attire, complete with cape and top hat, and heading out for a night on the town, to do all those things that “gentlemen like me” dare not do.

If to this point we have sympathised with Jekyll, from hereon in we can do so no longer. His decision to release Hyde is made deliberately and with fore-thought, and knowing what the consequences must be, as is revealed by Jekyll’s flight to Muriel, which is driven as much by fear of himself as by desire for her; and this puts him beyond the pale. And if Jekyll here manages to convince himself that he is not really betraying Muriel and his vows of love to her, and hers to him – that what he does as Hyde somehow doesn’t count – then he is guilty of a worst sophistry, a worse self-deception, a worst piece of hypocrisy, than anything committed by those people he so scornfully condemned for “denying their instincts”.

In truth, the real audacity of Mamoulian’s concept of Hyde lies less in its design than it does in its execution, particularly during Jekyll’s first two transformations. The Hyde we become acquainted with at first is, well, rather a jolly chap. The exuberant physicality of March’s performance here gives us one of the screen’s most unusual interpretations of Hyde. He is delighted to be here, delighted to be “free at last”, delighted with everything. He laughs and runs and stretches, feeling his existence; most famously, as he steps out into the rainy night, he sweeps off his hat and lifts his face to the sky, allowing the rain to fall onto his face and hair, and enjoying the sensation immensely. If we are already well-acquainted with Henry Jekyll’s ego, here we meet his id. Hyde is animal instinct incarnate, the most primitive part of Man, freed of every evolutionary and social restraint.

Hyde sets out, looking for a little fun—and of course he heads for Soho, and the rooms of Ivy Pierson (on which, we are now permitted to see, a sign reads, “Lodgings by the day or by the week”, another dead giveaway of Ivy’s profession). She is not home, but her landlady directs Hyde to the Variety Music Hall—and for her pains is on the receiving end of an obscene joke, as Hyde, from beneath the staircase, thrusts his cane up her skirt.

Laughing uproariously, Hyde then heads for the Variety, where two dancers in provocative costumes entertain a mingled crowd of lower-class men and women as they drink and laugh and flirt—and more.

We get two of my favourite moments in the whole film in this sequence, evidence in their marvellous detail of Rouben Mamoulian’s investment in this film, and also of his sense of humour. First, as Hyde crosses to one of the tables on the hall’s mezzanine, his eyes light upon a woman in a backless dress. Without thinking, Hyde runs an appreciative hand across the invitingly bared skin, causing the woman to gasp and jump. Settling at his table, Hyde then orders champagne, which we soon gather is an order not often placed at the Variety: the bottle arrives accompanied by beer glasses.

The camera pans around, and we learn that whatever else the Variety is, it is also a hunting-ground for the local tarts. Sure enough, Ivy is there, alluringly dressed, and inviting custom with her trademark song (“Champagne Ivy is my name / Good for any game at night, my boys…”). She already has a punter on the hook when the waiter sidles up and tells her that “a gent” wants to drink with her. Ivy is at first unimpressed, until the waiter, meaning well, warns her that, “He’s not one to be trifled with.” Balanced on a knife-edge, Ivy allows her curiosity to get the better of her – “I’ll take a chance!” – and so seals her own doom.

It is easy to think of the story of Dr Jekyll And Mr Hyde in fairly simplistic moral terms, but clearly, Mamoulian’s interpretation of this seminal tale was, if not quite the same as Stevenson’s own, equally complex. The Hyde who is at first released is not in fact “evil” in the ethical or religious sense, but something more primitive and fundamental. The original screenplay for this film had Hyde guilty from the outset of all sorts of deliberate cruelty, but Mamoulian rejected all of these scenes (including one of the novel’s most infamous, the trampling of a child), recognising that cruelty, that evil, is the product of calculation. Hyde acts and reacts, but never stops to reflect—at least not at first. His anger and his violence, even his desire for Ivy, are, like his initial joie de vivre, untempered impulse.

But this changes over time until evil, true evil, does emerge, and it is through Hyde’s interaction with Ivy that it shows itself.

Ivy’s initial reaction to Hyde is one of conflicting urges, her revulsion wrestling with her pragmatism, and the two bound together by a strange and deadly kind of fascination—that of a bird hypnotised by a snake. She vacillates as he offers her a life of luxury, her awareness of the practical advantages of such an arrangement overcoming her physical aversion—but only for as long as Hyde isn’t touching her; as soon as his busy hands come into play, her instinctive loathing of him takes over.

Still, Ivy is on the verge of succumbing when her abandoned customer comes storming up, furious at being discarded, and for such a – thing – as Hyde. In a flash, the pure, unrestrained, animal Hyde shows himself, smashing the champagne bottle and going on the attack. This outburst of violence is enough to tip the scales the other way, and Ivy tries to flee—but it is already too late…

The Ivy we see next is a far cry from the brash, merry girl who made a play for Jekyll and laughingly enticed the patrons of the Variety; in her place is a quivering wreck, who jumps and gasps at every sound, her eyes wide with fear.

It is in these scenes that Dr Jekyll And Mr Hyde reaps the fullest benefit of the time in which it was made, exploiting its relative freedom in order to venture into the very darkest corners of the human experience. We know, after all, that Ivy is a prostitute, at a time when the law offered little enough protection for any woman, and none at all for one of her profession. We are well able to imagine what Ivy must already have seen and submitted to in her life. Her helpless terror in the face of Hyde, so vastly different from the defiant cheerfulness we have seen in her to date, conjures up a vision of horrors almost past comprehension. Although Hyde is certainly physically brutal – there are finger-marks all over Ivy’s arms – it is even worse when he is not: the misery of expression and the utter rigidity of body with which Ivy responds to Hyde’s rough, eager caresses speak a suffering almost beyond human endurance.

But Hyde is no longer just a creature of the flesh: he has learned how to torture his victim psychologically, as well. He does so here, dangling the possibility of his departure before her eyes and snatching it away again; forcing her to speak, to sing, to beg him to stay with her, turning her into his puppet. With absolute deliberation, Hyde drives Ivy into a fit of hysteria, and then into emotional and physical collapse—and it is then, his intention clear, that he takes her into his arms. Here, indeed, is evil.

And what, in all this, of the saintly Dr Jekyll? We sympathise with Jekyll as he rebels against the suffocating conventionality and hypocrisy of his society, but with Hyde’s exploits – and he is far from done, even yet – there comes a sense of the film pulling the rug out from beneath our feet. We can understand that Jekyll’s passions, barely restrained even when he is at his best and most positive, might give rise to an alter-ego in whom those very passions, unchecked either by the conventions of civilisation or by Jekyll’s better self, become a destructive force; but the extent of the violence of which Hyde is capable, the savagery to which he descends, is startling. Again and again we remind ourselves, this is Jekyll; and it is here, in its suggestion that the dark and cruel desires made manifest in Hyde might be found deep within even the kindest, the best intentioned, the most gentle and loving of men, that this film becomes truly frightening.

During Hyde’s reign, we do get one brief cutaway to Dr Lanyon calling on Poole, sent by General Carew to see why Jekyll hasn’t answered any of Muriel’s letters. Poole’s response is ambiguously phrased, leaving it uncertain whether he has seen Jekyll at all since his transformation, but it does include a reference to “Jekyll” coming and going by the back door of the laboratory. We might wonder what he’s coming and going for: he isn’t stopping to see his patients, and he certainly isn’t reading Muriel’s letters. Is he coming back to take more of his draught, then? – to “top up” Hyde? – to keep Hyde in existence?

Of course, one of the most tantalising, and most unsettling, questions about this story is that of how much Jekyll knows of Hyde and what he does. If he is, indeed, coming and going during this time, it is hard to think that he is not fully conscious of Hyde’s actions.

That Hyde knows Jekyll is clear enough; knows him and scorns him: he certainly includes him as he rails against, “Those nice, kind gentlemen – cowards! weaklings!” It is Hyde who learns of Muriel’s return to London, via a paragraph in the newspaper; and apparently, it is also this knowledge that provokes Hyde’s most savage tormenting of Ivy: a fact that takes us into a psycho-sexual realm almost too horrible to contemplate.

The most serious flaw in this adaptation of Dr Jekyll And Mr Hyde, as indeed it is in almost all screen adaptations of the story, is its inability to reconcile Jekyll’s theories with Jekyll’s actions. Cinema’s invention of a saintly Dr Jekyll introduces a dramatic paradox into the story that no version has succeeded in addressing. Rouben Mamoulian’s rendering of the tale probably suffers from this more than any other, because of the heights to which it raises its Jekyll during its opening scenes, in which he is all but beatified. The Barrymore version suffers similarly, but explains the contradictions by giving us a naive Jekyll unaware of his own darknesses. In contrast, Mamoulian’s Jekyll knows himself, his instincts and his impulses, only too well. No real solution is possible here. The best that the film can offer is an unnerving ambiguity; a refusal to answer, one way or the other, its own most painful questions.

When we finally do see Jekyll as Jekyll, he is grimly contemplating Muriel’s hitherto disregarded letters – and the key to the back door of the laboratory – and we get a most intriguing piece of dialogue. In the novel, Stevenson makes full use of Jekyll’s house and its twin exits, the front door that opens into the fashionable part of town, and the door of the laboratory that leads to a more disreputable area. The symbolism is obvious enough, and the film exploits it as the novel did; but with the playing of this scene there’s a hint of a further meaning, as well. With deliberation, Jekyll discards his back door key, announcing to Poole, “I’ll have no further use for it. From now on, I’ll only use the front door!” – and we can only wonder if, obliquely, we are here being given an intimation of Hyde’s particular sexual tastes.

Jekyll’s next move is also revealing: he sends Poole to Ivy with fifty pounds. The size of the pay-off is suggestive, but not conclusive. Jekyll is at this point distracted to the point of carelessness, and he fails to guard against a mention of his name. As it turns out, it means nothing to Ivy herself, but it does to her landlady, Mrs Hawkins, who has come to tend Hyde’s “farewell gift” to Ivy: whip marks across her back. Speaking enthusiastically of “the celebrated Dr Jekyll” and his work amongst the poor, Mrs Hawkins speculates that Ivy’s sufferings have somehow been brought to his attention, and urges the girl to go for him for help.

Jekyll, meanwhile, is trying to explain himself to Muriel, justifiably hurt by his behaviour; what she knows of it. (There is a recurrence of the split-screen here, linking Ivy and Muriel in a particularly discomforting way, Ivy with her whip marks being contrasted with Muriel’s complaint that Jekyll has, “Made me suffer so.”) Jekyll never draws near a real confession, getting only so far as admitting to “playing with dangerous knowledge” and, as a consequence, experiencing an “illness of the soul”.

Jekyll’s plea to Muriel that she help him “find his way back” has the desired effect, and in the next tussle with General Carew, Muriel is triumphant, as her father finally concedes defeat and agrees to an immediate marriage. The terrible irony in all this is that, had Muriel been a “bad” daughter sooner, if she had defied her father instead of taking his caprices as law, he might well have given in weeks earlier—and this entire tragedy might have been averted.

But the implication of this sequence goes deeper than that, and in a way that condemns Jekyll entirely. The very fact that Muriel is now so willing to defy her father, the eagerness with which she responds to Jekyll’s pleadings, and with which she kisses him, tells us clearly enough that Jekyll was not the only one suffering loneliness and frustration during their separation; but Muriel, unlike Jekyll himself, was strong enough, and committed enough, to endure it.

Be that as it may, Jekyll’s reaction – and Mamoulian’s – to Carew’s capitulation is an outburst of joyful acts and imagery; all of which comes crashing to earth as Poole announces, “A Miss Pierson.”

Jekyll’s behaviour here is certainly equivocal. He repeats the name – “Pierson?” – as if he never heard it before, but his whole aspect suggests just one thing: how much does she know? He faces her squarely, however. Ivy, dressed in her pitiful “best” and dwarfed by Jekyll’s mansion, enters nervously, stares at him in disbelief—and then breaks into a delighted smile. “Why…it’s you, sir!” Her rescuer. Her hero. Her white knight.

Poor Ivy is quite heart-breaking in this scene, as she implores help from the man who has caused all of her misery—but not before she has given him his money back. In a gesture of self-loathing, she shows Jekyll her back, bearing the marks of Hyde’s whipping of the night before, before breaking into an frenzied account of her sufferings at her tormentor’s hands, begging Jekyll, if he cannot help her directly, at least to help her kill herself.

And again, we cannot truly tell what Jekyll is thinking and feeling, how much he knows, how much he remembers. But there is one horribly telling moment, one with a significance far beyond the confines of this film: “Why didn’t you get help?” demands Jekyll tersely. “Why didn’t you go to the police?”

Why didn’t you go to the police? That’s what they always say, isn’t it, to victims of domestic abuse? Why didn’t you leave, why didn’t you help yourself? And they continue to say it, despite the ever-increasing number of cases in which women who do leave are hunted down and murdered. Ivy’s hysterical cries are an answer that stands today as much as it did then: too terrified to leave, too terrified to seek help, too terrified to move, almost too terrified to breathe…

The scene ends with Ivy literally at Jekyll’s feet, offering herself to him in a confused jumble of motives: love, fear, desire, hero-worship. And Jekyll, although aghast at his own culpability, although moved beyond expression by her plight, is also…tempted. For a moment he responds, taking her face in his hands – just as Hyde did – and then he puts her away: “I give you my word – you will never be troubled by Hyde again.”

But not even the word of her demi-god is enough to reassure Ivy, and she breaks into another telling outburst: “He’ll come back and he’ll kill me! He ain’t human! You don’t know him!” At last, however, Jekyll’s reiterated, “Believe me, believe me,” calms her. He again presses his money upon her – she takes it, we feel, as much as a memento of him as anything else – and sends her on her way. Jekyll is left staring broodingly into the fire.

When we next see him, though, he is happily departing for the formal dinner party at which his and Muriel’s imminent marriage is to be announced. Jekyll goes on foot, walking through the park, stopping to enjoy the sight and sound of a nightingale, which inspires him to a little Keats—until the simple beauty of the scene is brought to a violent end, as a cat slinks up the tree…

The sickened Jekyll is provoked to a bitterly mocking repetition of the poetry he quoted so joyfully only a moment ago – “Thou was not born for death” – and then gazes down in sudden horror at his hands…

And with this scene of primal blood-letting, Hyde is back: back with a vengeance, and without benefit of Jekyll’s potion; and while the killing of the bird is the immediate catalyst, it is impossible not to feel that Jekyll’s second encounter with Ivy is the true and deeper cause.

Hyde’s steps turn not to the West End, but towards Soho. Here, juxtaposed, are two of Mamoulian’s most weighted split-screens, first Hyde disappearing across the park, as Muriel waits in vain for Jekyll; and then Muriel’s waiting with Ivy’s champagne-soaked celebration of Hyde’s permanent departure. Of course she believes it’s permanent: Jekyll told her so…

More than a little tipsy, Ivy wavers about her rooms, sipping champagne and giggling to herself, and finally toasting her own reflection in the mirror, fervently wishing perdition to Hyde and hoping that Jekyll thinks of her as she thinks of him. “He’s an angel, he is” she sighs. “Here’s to you, my angel.”

And in what may be the supreme moment in all thirties horror, the door swings open to reveal—Hyde.

That Ivy is doomed we know at once; but Hyde cannot be content with merely killing her. He hunts her about the apartment first, throwing her own words to Jekyll back in her face, tearing her pathetic dreams to shreds, and then, as his hands close about her throat, revealing the truth: “I – am – Jekyll!”

Ivy’s despairing screams bring – too late – a crowd. Hyde breaks through the efforts to stop him and dashes through the darkened streets to the back door of the laboratory…only to realise that he doesn’t have the key. An attempt to gain entrance by the front door fails when the horrified but efficient Poole slams the door in his face; and Hyde, in desperation, must seek help elsewhere.

We get the last of Mamoulian’s split-wipes here, a sardonic twin-framing of the people who are, by now, the two men in Muriel Carew’s life: a seething, panicked Hyde, and a seething, furious father, the latter of whom – justly, at last – forbids Muriel ever to see Jekyll again. Muriel, loyal to the end, continues to insist that something terrible must have happened, to keep Jekyll from her.

Meanwhile, Dr Lanyon reaches home to find a note waiting for him, a note in Jekyll’s handwriting, begging him to collect certain items from Jekyll’s laboratory. Lanyon does so; but when Hyde calls for them, he finds Lanyon armed with a pistol and in a distinctly uncooperative mood. Hyde’s furious and threatening attempts to force Lanyon to let him go fail: Lanyon insists upon knowing what has happened to Jekyll. In a moment that may stand as the definition of the expression, Be careful what you pray for—Hyde shows him.

The candles are guttering by the time Jekyll has told it all. Incredibly, it is less the fact of what Jekyll has done, including the murder of Ivy, that draws Lanyon’s wrath, than his rebelliousness and his flouting of social convention, which Lanyon manages to equate with blasphemy. “There is no help for you here – and no mercy beyond,” he pronounces.

Lanyon’s blinkered outrage – God is not just an Englishman, we gather, but an English gentleman – leads into one of the most interesting and misinterpreted aspects of this film. After decades of science fiction and horror films featuring godless scientists, and scientists who want to be God, or just to tamper in God’s domain, it comes as something of a shock to realise that this story is being told from a conventionally religious standpoint. When Jekyll speaks of the soul at the beginning, he isn’t just using a general term, as his addendum – “the human psyche” – might imply; he means it in the absolute Christian sense, as his anguish at the conclusion of the film makes clear.

The final section of Dr Jekyll And Mr Hyde is curiously paced, particularly the drawn-out scene in which Jekyll tries to do penance for his crimes and transgressions by renouncing Muriel, but it is important that we recognise what is intended here. Jekyll’s agonies, his prayers, his visions of hell and damnation, are all meant completely literally; and we rob this film of some of its power if we do not understand this.

Jekyll goes to Muriel to perform his act of penance. There is a heart-breaking irony about Muriel here as, in her desperation, she now defies her father without hesitation, insisting upon Jekyll being admitted when Carew tries to forbid him the house and saying all the things that she should have said earlier, when they might have done some good. “I haven’t fought for him enough,” she admits.

Muriel’s rebellion here, too late though it comes, is vitally important in terms of the overall message of the film. Jekyll’s hysterical condemnation of himself, his repudiation of all that he has done and intended, lends a reactionary tone to the tale. For a few horrible moments, the stifling prejudices of General Carew and Dr Lanyon seem to have gained dominion—but Muriel’s behaviour here puts that into better perspective. Going too far is not desirable, but neither is going nowhere, doing nothing, daring nothing. A little rebellion now and then, we see, is a good and necessary thing.

Despite Muriel’s courageous and frantic loyalty, the passionate embraces and the kisses with which she tries to hold him, Jekyll goes through with his renunciation of her—kneeling at her feet as Ivy had knelt as his. “Do you hear me, O God?” he cries, looking heavenward. “This is my penance!” He leaves Muriel upon these words, striding out into the night, but gets only so far as the Carews’ terrace, from where he gazes in painful longing through the curtained window at Muriel, sobbing in despair at her piano.

And then it happens…

And Hyde it is who makes his silent way back into the house, gazing lustfully down at Muriel and then putting his hands upon her. She, believing that Jekyll has returned, swings around joyfully—and screams.

General Carew and the butler, Hobson, come rushing to her rescue. Their struggle spills out onto the terrace and into the garden, where Hyde, getting Carew at his mercy, crushes his skull with two swift blows from his walking-stick, delivered hard enough to snap it in two. And if anything can challenge the tormenting of Ivy for sheer horror, it is surely this moment, when we know that Jekyll’s impulse is speaking through Hyde.

Cries and screams bring the police, and then the populace in general, as Hyde flees for the last time. This time he is able to enter Jekyll’s house by the front door, and rushes to the laboratory, when he begins to mix a draught…

But it is no use. By now Lanyon is at the Carews’, and he recognises the shattered remains of the walking-stick that lies by the General’s dead body.

Throughout this last section of the film, from the scene of Jekyll’s confession to Lanyon, Jekyll is framed so as to place him below all those to whom he speaks, Lanyon, Carew and Muriel in turn, and now the police, who break into the laboratory with Poole’s assistance. The visual symbolism of all this goes a step further here, as Jekyll is at last photographed through that fire burning perpetually in the laboratory, and by the side of the skeleton hanging in the corner, at which Jekyll smiled so wryly and companionably upon embarking upon his first transformation.

Jekyll tries to send his pursuers away, claiming that Hyde has been and gone; but as the police follow his instructions, Lanyon arrives—insisting that the guilty party is still in their midst. “There!” he cries, pointing an accusing finger. “There’s your man!”

And before the terrified and disbelieving gazes of those gathered, Jekyll undergoes another transformation…

Hyde makes a desperate and violent effort to escape, but when he seizes a knife, he is shot down by the detective who arrived with Lanyon. As he collapses to lie amongst the smashed debris of the laboratory, he transforms for one last time, his hideously distorted features returning to those of Henry Jekyll. Poole weeps for his dead master, but little other comfort is to be found in this ending. Also for one last time, we see Henry Jekyll through the leaping flames of his fireplace; it is with the implication of this image that we are left…

Well, perhaps not. The frankly religious underpinnings of this tale leave us with the hope that even Jekyll is not beyond redemption, even without our last shot of him, calm and beatific in death. There is, in any case, a sense of genuine tragedy and loss about the final scene of this film, this story of a man who reached so high and fell so far, and so hard. We are undoubtedly some distance from Stevenson here. Nevertheless, in their belief in the inescapable duality of man the two versions of the story are certainly in agreement—although in this respect Stevenson was, perhaps, rather more pessimistic than Rouben Mamoulian.

That Mamoulian believed utterly in the story he was telling in evident in every frame of this film. Visually, Dr Jekyll And Mr Hyde is a masterpiece, a treasure-trove of experimentation and imagination, of the director’s brilliance and the cinematographer’s art.

All of this, however, would mean little if the film were only visual. Instead, Mamoulian’s artistry goes hand-in-glove with the courageous performances at its heart. I again include Rose Hobart here, whose Muriel does change and grow, and who succeeds in showing us the sexual woman behind the conventional “good girl”. However, it is of course Fredric March and Miriam Hopkins who dominate this film. It is true that the extravagance of March’s contributions as Jekyll and as Hyde, and the floridness of his language, may be a bit too much for modern tastes, but we cannot doubt that in all this he was making Mamoulian’s vision flesh. He gives, in any case, an extraordinary, and extraordinarily brave, pair of performances, and fully deserved the partial acknowledgement that he won from the Academy (in fact, he deserved rather more).

However, no matter how often I watch this film, in the end it is always the image of Miriam Hopkins as Ivy that lingers afterwards: laughing, provocative Ivy; tragic, terrified Ivy. It is bad enough that Fredric March had to share his Academy Award – and with Wallace Beery, of all people – but that Miriam Hopkins wasn’t even nominated for her performance in this film is a travesty. I guess you don’t get rewarded for playing bad girls; you just get remembered.

All that said, this is certainly not a film without flaws. There are problems in its pacing, in its dialogue, and in the rather wooden characterisations amongst the supporting cast; although when you consider the transitional era during which it was produced, these shortcomings are neither unusual nor much to be wondered at—and nor, in fact, do they ultimately amount to all that much in terms of the film as a whole. Rouben Mamoulian’s version of Dr Jekyll And Mr Hyde is a daring, wildly imaginative and above all whole-hearted production and is, in my opinion, still the best of all the seemingly countless cinematic renderings of Robert Louis Stevenson’s seminal tale.

.

Want a second opinion of Dr Jekyll And Mr Hyde? Visit 1000 Misspent Hours – And Counting.

Footnote: Just keep telling yourself…it’s only a movie…it’s only a movie…

the ultimate warning of the importance of drug purity. It doesn’t seem to be mentioned here, but in the novel, the original potion was only effective because of some impurity in one of the ingredients, which could never be duplicated, so Jekyll runs out, and is stuck as Hyde.

And just what is the word, “E-e-yow”, anyways (from the movie poster)? some cousin of Tarzan’s yell?

As you mention, in the novel, Jekyll is not a saint. In fact, it’s implied that he’s looking for the potion so he can ‘indulge’ as he has in the past, without any fear of recognition. When he decides he must be one or the other (before the potion runs out), he is leaning toward choosing Hyde, for lots of fun, but he realizes he would miss Jekyll, with all of his inadequate virtues. The potion running out makes the decision for him.

Remember, always use pure ingredients.

LikeLike

…AND write your experiments up properly!

No, there’s never any attempt to convey how the separation is actually being accomplished.

I included that particular trade ad just because it’s so awful. What a marvellously inappropriate way to advertise the film!

LikeLike

I first saw noticed the good girl/bad girl thing in the first Flash Gordon film serial (1936). When it’s a choice between Jean Rogers (screams, faints) and Priscilla Lawson (shoots people while escaping), well….

Gentlemen like him, traditionally, took advantage of those amusements, brought the microbiological consequences home to their wives, and then blamed the latter for straying…

One could reasonably argue that the planning Hyde is no longer the pure id, but has use of Jekyll’s prefrontal lobes as well. I wonder, now, how effectively one could make a film of this story with no physical transformation at all, with the “compound” as a mere excuse for Jekyll to act as he’s been capable of all along, but has been suppressing… perhaps with an actor who could look different just by facial experssion.

Perhaps Jekyll expects to “get it out of his system”, to release the impulses and leave their consequences behind. That certainly seems to have been a Victorian attitude.

LikeLike

In the original story, there were no women of any kind mentioned by name (only by ‘unmentionable’ suggestions). But Hollywood always likes to throw a little romance at the screen. It was the same with The Picture of Dorian Gray. His first victim is described in the story (he does not have his way with her as in the movie, she just turns into a bad actress once she falls in true love, so he dumps her). But the little girl growing up to become his fiancée is nowhere in the original.

Night Gallery did the same thing with a lot of stories. I had read the original stories, and was always surprised to find a woman on the screen.

LikeLike

The Most Dangerous Game, too. There are no women at all in the original story, and the Hollywood version put in the usual love interest.

LikeLike

Well…I’ve said enough on THAT subject by now, but would reiterate that she isn’t really “the love interest” in the usual sense, because there isn’t time for anything like that.

As I touch on there, it was a standing production order to write in a female character where there wasn’t one, so it wasn’t about doing it, it was how they did it—how well it was blended in thematically. Both Dr Jekyll And Mr Hyde and The Most Dangerous Game find a way beyond the tokenism; Dorian Gray not so much.

LikeLike

Many serials have a good girl / bad girl thing going on, because the nature of them paves the way for it. Ben Wilson, who was one of the major serial actor / producers in the silent era, might have been the first in that context. He was married to Neva Gerber, who was nearly always cast as “good girl” opposite himself; but he often included a “bad girl” in his stories too—usually “bad” purely in the criminal sense, though. 🙂

That’s more or less what they were attempting with Spencer Tracy, I think.

The Victorians accepted that men were naturally “animalistic”**, which is where the tacit support for prostitution came from—despite what they knew of the likely consequences. It wasn’t “nice” to feel that way about your wife, and of course she didn’t want you to… This is where this version of Jekyll is so unforgivable, because clearly he knows better than that and doesn’t have these hang-ups about his relationship with Muriel..but he still can’t / won’t control himself.

(**This is one of the many things that John Stuart Mill called his society out on: if men were naturally bad and women naturally good, how did it make sense to subjugate the good to the bad?)

LikeLike