“Kill! Then love! When you have known that, you will have known ecstasy!”

[aka The Hounds Of Zaroff]

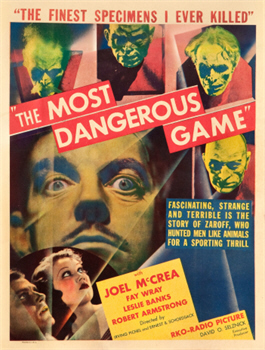

Director: Ernest B. Schoedsack and Irving Pichel

Starring: Joel McCrea, Leslie Banks, Fay Wray, Robert Armstrong, Noble Johnson, William B. Davidson, Hale Hamilton, Landers Stevens, Phil Tead, Steve Clemente, Dutch Hendrian

Screenplay: James Ashmore Creelman, based upon the story by Richard Connell

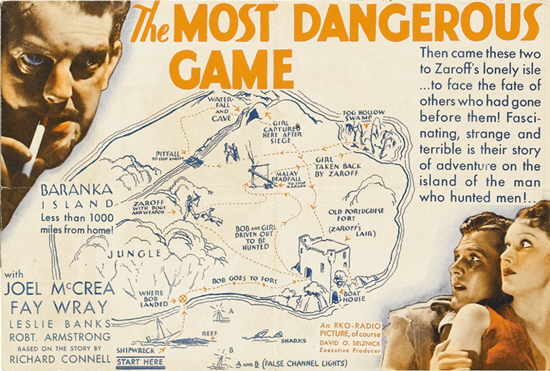

Synopsis: As a private yacht passes through the waters surrounding an island group in the Pacific, the captain (William B. Davidson) becomes concerned about two channel markers, which to do not seem to be in quite the same position as is marked on his chart. He carries his doubts to the yacht’s owner (Hale Hamilton), who ordered that the yacht go between the islands to save time, rather than around them. One of the passengers, known as ‘Doc’ (Landers Stevens), agrees with the captain that the waters are dangerous; but the rest insist on pressing ahead. Doc’s travelling companion, Bob Rainsford (Joel McCrea), agrees with his friend that perhaps they shouldn’t take any chances. The others only laugh, as Rainsford is famous as a risk-taking big-game hunter and author. The passengers examine some photographs taken during his last expedition. Doc criticises the idea of hunting being “sport” and, when Rainsford defends it, asks wryly if he would be willing to trade places with the animal? Annoyed, Rainsford declares flatly that the world is divided into two types of people, the hunters and the hunted—and that he is simply fortunate in being the former. The argument comes to a dramatic end when, without warning, the yacht hits a reef and is ripped open. The men below decks have no chance to escape; while, as the yacht rapidly sinks, the rest are cast into the water either to drown or be taken by sharks. Only Rainsford escapes with his life, swimming to an island and collapsing on the shore… When Rainsford wakes, it is to the sound of dogs barking and a strange, wild cry. Realising that there must be people on the island, he sets off through the jungle—eventually coming across the startling sight: a stone fortress built high on a cliff. Making his way to the building, Rainsford finds the front door open, and steps into an almost medieval scene, a huge open vestibule lit with candles and with an enormous fire burning. A noise from behind him makes Rainsford swing around, to where a grim-faced servant has locked the door. Rainsford tries to explain himself, but the man remains silent. It is a voice from the sweeping stone staircase that answers him, explaining that Ivan (Noble Johnson) does not speak at all. Rainsford is startled to see an urbane man in evening clothes descending towards him; he introduces himself as Count Zaroff (Leslie Banks). When Rainsford explains that he has been in a shipwreck, the Count tells him commiseratingly that he is not the first; that, indeed, survivors of a previous accident are still with him. He offers Rainsford shelter and a new set of clothes, ordering Ivan to show him to a room upstairs. When Rainsford comes down again, he is introduced to his fellow-guests, Eve Trowbridge (Fay Wray) and her brother, Martin (Robert Armstrong). Eve tells Rainsford that she, Martin and two sailors survived their own wreck in a lifeboat; and that they are now waiting for the island’s only launch to be repaired so that they may be conveyed to the mainland. Martin asks Rainsford about himself, only for Zaroff to interrupt, observing that Rainsford’s fame as a hunter precedes him, and that he, Zaroff, is also passionately devoted to the sport. He tells Rainsford that after a life devoted to hunting, at one time he was dismayed to find himself growing bored with it. Now, however, on his private island, he has reinvigorated his passion, by providing for himself the most dangerous game of all…

Comments: Cinematic histories have a tendency to reduce The Most Dangerous Game to a mere footnote in the story of King Kong, which (among other things) gets the story the wrong way around. It was The Most Dangerous Game that was Merion C. Cooper’s first choice for a project when he was hired at RKO early in 1932; for which in turn he hired Ernest B. Shoedsack to direct, and cast Fay Wray and Robert Armstrong; and for which those famous jungle sets were built. Numerous other touches in King Kong, including the sound effects and music, also had their origins in the earlier film.

But of course, the real injustice in this footnoting is that it creates a dismissive air around what is, on its own terms, a gripping horror-drama—as well as the first screen rendering of a theme which has since become one of cinema’s most enduring.

In fact, as far as popular culture goes, Richard Connell’s short story, The Most Dangerous Game, is the gift that just keeps on giving.

First published in Collier’s in January of 1924, The Most Dangerous Game is the story of professional hunter Sanger Rainsford, who is cast ashore on an island occupied only by General Zaroff and his servants. Zaroff knows Rainsford by his books, and over dinner the two men discuss their mutual passion for hunting. Zaroff confesses to Rainsford that his own skill at the hunt is such, it was robbing the sport of the danger which he craved—until he began to stock his private island with a new sort of animal, which he refers to as “the most dangerous game”. Rainsford’s puzzlement turns to horror as Zaroff goes on to explain just what this dangerous new animal is, and he refuses point-blank to participate in Zaroff’s sport—at least, as a hunter. At length he is forced to participate as the only way of saving himself. Armed only with a hunting-knife and his own wits and skill, Rainsford is sent out into the jungle. If he can evade Zaroff for three days, he will be granted his life…

The Most Dangerous Game was an immediate sensation, and went on to secure the year’s O. Henry Memorial Award for short fiction. Over time it has become not only one of the most anthologised short stories of all time, but one of the most frequently adapted—being used as the basis for a myriad of films, television episodes and radio plays. The central concept of man hunting man is one that has proved endlessly fascinating; while Connell’s refusal to expand overtly upon the themes embedded in his tale has allowed for wide range of interpretations in which human beings are hunted for sport, as originally conceived; or for punishment; or for the entertainment of others: sometimes purely within an action framework, sometimes with more serious intent.

The 1932 adaptation of The Most Dangerous Game was not only the first, but almost matches its model in terms of the efficiency of its story-telling. There are, however, some significant differences between the two—including the provision within the film of a moral framework, though not necessarily the one we might expect.

In keeping with the mores of its time, The Most Dangerous Game takes hunting as a sport very much for granted. It draws a line according to what is being hunted, but otherwise does not question the morality of the activity. Yet produced only eight years later, The Most Dangerous Game does question it—and with a vigour that endears the film to those of us who to whom the thought of killing an animal merely as an amusement is abhorrent, and in a way that throws an intriguing shade over the film’s central character.

In spite of my attempt to separate The Most Dangerous Game from the surrounding story of King Kong, there is no question about the impact which the later film had upon it. Merion Cooper initially conceived his first RKO film as a fairly lavish ‘A’-production—and to this we can probably attribute the hiring of a co-director for Ernest Schoedsack, in the form of Irving Pichel. Schoedsack had not directed a sound film before; while Pichel, with his stage background, was accustomed to working directly with actors. He was assigned the dialogue scenes, while the action sequences were left under Schoedsack’s direction.

However, as the costs associated with King Kong began to escalate, the budget allocated to The Most Dangerous Game was slashed and its production schedule significantly shortened. Cooper kept both of his directors, but he cut his spending in other directions by seeking ways in which his two productions could utilise the same resources—including their casts. The shooting of The Most Dangerous Game was ultimately organised around the availability of Fay Wray, as she was involved in or freed from King Kong’s pre-production special-effects work.

It could reasonably be argued that what started out as a fairly ruthless exercise in cost-cutting ended up shaping a film whose brief running-time and rapid-fire pace are among its virtues. In fact Merion Cooper and Ernest Schoedsack finally embraced what had initially been forced upon them, striving to create a story free of padding and diversions from its central plot, but full of suspense. Their first cut of The Most Dangerous Game ran only 75 minutes; but the film would be shortened even more before it went into general release, after preview audiences reacted badly to what was, at the time, some brutally shocking material. When The Most Dangerous Game opened in September of 1932, it ran a breathless 63 minutes.

The film hits the ground running, setting up both its physical and moral geography within its first few minutes—and introducing its protagonist in distinctly ambiguous terms.

This was an important early role for Joel McCrea, and helped to establish him as a leading man. His character, Bob Rainsford, is marked from the beginning as the film’s hero: when he first appears, he is dressed all in white; while the supporting characters speak of him in a way that both indicates their reliance upon his judgement, and their admiration of his courage.

Yet almost immediately, the screenplay begins to cut the ground away from under Rainsford’s feet. We learn that Rainsford is a professional big-game hunter and author, and that another of the characters (somewhat misleadingly dubbed “Doc”) has acted as photographer on his most recent expedition. It is evident that Doc did not enjoy the experience; and as Rainsford exclaims in satisfaction over some of the photographs taken – one in particular, showing Rainsford in the very process of killing a tiger – Doc begins to ask some uncomfortable questions—remarking upon the inherent contradiction in animals which kill for food or to defend themselves being called “savage”, while men who kill for sport are considered “civilised”.

Doc: “I asked you a question!…I asked if there would be much sport if you were the tiger instead of the hunter?”

(The photograph of the tiger was doctored, of course, to put Joel McCrea in frame with animal—but the photograph itself was only too real. In their earlier days, Merion Cooper and Ernest Schoedsack travelled the world together, capturing film-footage and photographs for use in documentaries and magazines, and as stock footage. On these expeditions, Schoedsack also acted as guard—and in the encounter with the tiger, as he later put it, he reached for his camera first and his rifle second. That he subsequently used his own photograph as a prop in The Most Dangerous Game, in effect to criticise hunting, adds an intriguing meta-note to this scene.)

It is evident that Rainsford would rather evade the issue and, when Doc refuses to let him off the hook, he makes a poor job of arguing his stance—producing surely the most asinine of all possible defences of hunting, that it’s sport for the animal too, that the animal really enjoys it. Doc immediately calls him upon the idiocy of this argument, asking wryly if Rainsford would choose to change positions with the tiger?

We come away from this tussle with a poor impression of Rainsford as a rather callow young man, who has never bothered to think through the implications of his actions. There is also an off-putting smugness in his final dismissal of the issue, in which he ranks himself amongst the world’s fortunate ones: a hunter, not the hunted.

And immediately, the yacht strikes a reef…

Around the key-note argument of Rainsford and Doc, we have also been informed of the concerns of the yacht’s captain with respect to an attempt to travel between, rather than around, a group of islands. In spite of his ominous reference to “coral-reefed, shark-infested waters”, the captain’s concerns are waved away by the majority of the passengers, including the yacht’s owner. The vessel therefore presses on through the channel near to a certain Branca Island, instead of taking the slower but safer passage around the island group, as the captain wanted.

The result of this is that the yacht is ripped open, sinking within minutes. The crew below have no chance, while the rest of the men, thrown into the water, are either drowned or taken by sharks. Only Rainsford escapes with his life, striking out for an island in the distance, and finally collapsing upon its rocky shore…

There are several points of interest in this brief but decisive scene. The sinking of the yacht may be footage cribbed from Willis O’Brien’s abandoned stop-motion film, Creation; if so, it’s not one of its better bits of model-work. The stunt-work involved in throwing everyone into the water was overseen by Larry “Buster” Crabbe—and he’s one of the men taking a dive. Footage of real sharks was cut in here, with one a shot of an animal chewing on a piece of bloody meat found so shocking, it was later censored. But perhaps the most important touch in the sequence is the sound of agonised screaming, as the crewmen are engulfed by scalding steam. This was the first film to make use of a lengthy reel of “test screams” recorded by Murray Spivak, the head of sound effects at RKO, but it was certainly not the last. One high-pitched cry in particular would be used again and again…most immediately, in King Kong.

The other important aspect of production that makes itself felt here is the score. In the early days of sound cinema there was, somewhat counterintuitively, a move away from movie music—partly because film-makers felt they had enough to worry about already, as they made the adjustment, partly because of a belief that audiences wanted dialogue and nothing but dialogue. It was 1932 before this situation changed significantly, with that year’s Bird Of Paradise (also starring Joel McCrea) becoming the first motion picture for which an original score was composed: the work of Max Steiner.

Steiner was the most important composer of the early sound era, eagerly grasping the new possibilities and taking the opportunity to experiment. This is another area where King Kong tends to overshadow The Most Dangerous Game—but if Steiner’s work on the former is now more celebrated, it was the latter on which he cut his teeth, first employing what would become trademark touches such as working thematic motifs into his music: in this case, including a hunting-horn in his orchestral arrangement.

Having fallen into an exhausted sleep, Rainsford is woken by the sound of barking dogs—and by a strange, terrified cry. Realising the implications of these sounds, he begins to scramble up the steep, jungle-covered slope that lifts from the shore, and finds himself gazing down at a stone fortress, lights in its windows confirming the presence of man.

At the front door of the mysterious building, Rainsford finds himself confronted by an unnerving detail—one with which the viewer has already been confronted, during the opening credits. The knocker which hangs upon the massive door of the fortress is in the form of a centaur, with an arrow in its shoulder and a woman in its arms. To use the knocker, one must grasp the woman’s body.

The door swings open, and Rainsford steps into the cavernous hall beyond. As he stares around in bemusement, he is not immediately aware that the door was opened for him: not until it is shut and barred by a wild-looking, bearded individual, who glares at him but does not speak…

Rainsford tries to explain himself, but wins no response. However, a voice does answer him, from the stone staircase that sweeps down into the hall. Rainsford swings around to find a man in impeccable evening dress moving calmly towards him. Explaining that Ivan is mute, the man introduces himself as Count Zaroff. He compels Ivan to smile—which only makes matters worse…

(Ivan is played by the African-American actor, Noble Johnson, who, more unusually but no less uncomfortably, was frequently called upon to undergo a reversal of the usual makeup process and plays his roles in white-face.)

Rainsford introduces himself and explains his situation. Zaroff is sympathetic but not surprised: the reefs have claimed victims before and, in fact, some survivors of the previous wreck are still with him. He welcomes Rainsford also, explaining briefly that his home was once a Portuguese fort, long since abandoned, which he acquired and adapted for his own purposes.

He then has Ivan escort Rainsford upstairs, to a room where he will find a bath and a change of clothing. Rainsford is grateful to have found such a refuge—but on the way up the stairs, he baulks upon observing the tapestry which hangs upon the wall. In its subject matter, it replicates and expands upon the detail of the door-knocker. In this case, the imagery shows the centaur being pursued by a hunter—with both, clearly, intent upon possession of the woman. In this rendering of the scene, the woman’s breasts are exposed. Rainsford casts an uneasy glance back at his host…

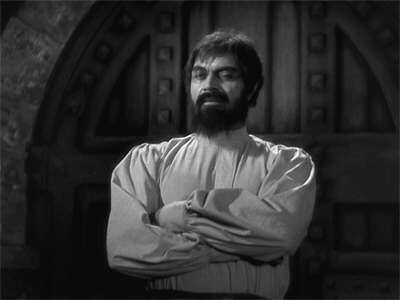

Count Zaroff is played by the British actor, Leslie Banks, who employs a florid Russian accent in keeping with his florid performance. We should not be misled by this, however, as there is more to the character than immediately meets the eye, or that the overt broadness of Banks’ portrayal would initially suggest.

At the outset, it is impossible not to focus upon the physical details of Banks’ characterisation: the scar on his forehead, which was fake, and the rigidity of his face and the slight protuberance of his left eye, which were not. Banks was severely wounded during WWI, with the result that the left side of his face was left paralysed. As he built his acting career, generally he would be photographed from one side or the other according to whether he was playing a hero or a villain. The Most Dangerous Game takes this one step further, often photographing him head-on, so as to convey both aspects of his implied personality at once.

Meanwhile, the way in which Zaroff strokes his scar at moments of tension invites the audience to infer that a head injury (inflicted, we learn, by an encounter with a Cape buffalo) is behind what he later reveals of himself. Yet the film does not insist upon this point; and we are free to treat it as a mere muddying of the waters, if we prefer.

Zaroff collects a refreshed Rainsford from his room and, when he declines any dinner, offers him instead, “Coffee, and most charming company.”

There is no female character in Richard Connell’s version of The Most Dangerous Game, which is basically a two-character drama. However, it was standard Hollywood practice to write a woman into everything – even war films usually managed to shoehorn in a mother, or a girlfriend, or even a resistance-fighter – and it would remain so until the studio system began to break down. (The Great Escape is generally considered the first major film to ignore protocol.) Of course, this was a practice that led to a great deal of tokenism – the creation, in film terms, of “the chick”, decorative but unnecessary – and while to an extent this is true of the character of Eve Trowbridge, as with Zaroff himself, it’s more complicated than that. Furthermore, the film’s rapid narrative prevents the development of any relationship between Eve and Rainsford other than the most fundamental one of mutual survival.

Merion Cooper and Ernest Schoedsack had worked with Fay Wray before, on the 1929 production of The Four Feathers (one of the last all-silent films), and they had no hesitation in casting her again. While it is now King Kong for which Fay is best known, and which endowed her with her famous title, “scream queen”, this was the culmination of a remarkable phase of horror film-making, with the length of that film’s production allowing Fay to appear not only in The Most Dangerous Game, but also Doctor X, The Vampire Bat and Mystery Of The Wax Museum, before King Kong was released.

Robert Armstrong, meanwhile, represents the most misunderstood aspect of The Most Dangerous Game—often interpreted as the film’s comic relief, in his role as Eve’s alcoholic brother, Martin.

In fact, not only is Martin annoying, but we were intended to find him so. In the time of Prohibition, Merion Cooper disapproved of the way alcohol was used in movies – the constant, casual consumption, and the prevalence of the “comic drunk” – and often included such a deliberately abrasive character in his films to off-set this. And really, the fact that it is impossible to tell the difference between Martin and the era’s numerous “funny” drunks rather makes Cooper’s point for him. If we understand that Martin is meant to be obnoxious, he’s a lot easier to take…because he really, truly is.

(Though Martin himself is not meant to be funny, the one overt touch of humour in this grim film comes via the sarcastic contempt with which Zaroff treats him. Conversely, that Rainsford actually does find Martin funny is perhaps intended as another tacit criticism.)

Zaroff introduces Rainsford to Eve and Martin, adding that they are meeting a celebrity. Here he hails Rainsford as a kindred spirit, informing him that he has read all of his books, and praising him on two points in particular: that he does not, “Excuse what needs no excuse”, and the fact that he considers hunting a game like any other, only with higher stakes. Rainsford asks Zaroff what he hunts on the island, and he replies ambiguously that he has invented “a new sensation”:

Zaroff: “You will be amused, I know.”

Zaroff then makes an impassioned speech about hunting, which he has made his life-long pursuit; indeed, his raison d’être. But, he adds, at length he reached a terrible impasse: he realised that his own skill was such, it was all too easy; he was getting bored with hunting… And with the loss of this passion, he adds, he lost all his others: for life, for love…

Zaroff is so taken up with his own memories, he is oblivious to the by-play going on between Rainsford and Eve. Indeed, as the viewer is aware, Eve has been striving to capture Rainsford’s attention since he came into the room, trying to catch his eye and emphasising certain words in her seemingly casual speech—but it is not until she deliberately knocks over her coffee cup while stressing the word “danger” that Rainsford understands.

Zaroff, meanwhile, is still describing his attempts to overcome his boredom—first by increasing the danger to himself, by hunting with more primitive weapons, like a war-bow. Finally, he concludes, he realised that what he needed was not a new weapon—but a new animal…

Zaroff: “Here on my island—I hunt the most dangerous game…”

Here the conversation takes an overtly unnerving turn, with Zaroff expounding to Rainsford – and only Rainsford – his ideas about the proper order of things: that one must “hunt” women only after the blood has been quickened by the actual hunt. Rainsford is clearly embarrassed by this suggestion, indeed by the topic itself, prompting a soft, mocking laugh from Zaroff: “You Americans…”

At length, Martin’s blundering causes Zaroff to change the subject. He sits down at the piano, which presents Eve with an opportunity to take Rainsford aside. As they occupy a window-seat a safe distance, she explains her fears in a hurried under-voice—all the while encouraging Rainsford to keep smiling, to look cheerful. She first nods out the window, alerting Rainsford to Zaroff’s pack of hunting-dogs, then tells him that there is actually nothing wrong with the island’s launch, repairs to which are Zaroff’s excuse for holding her and Martin there. Furthermore, the two sailors who were rescued with them from the wreck have now disappeared—first one and then the other, after Zaroff took them off to see his trophy-room…

(The dogs, some splendid Great Danes, were borrowed for the film from none other than Harold Lloyd. During production, it was decided they didn’t look fierce enough; and consequently, their coats were darkened and roughened up. When they were returned to their owner, he wasn’t the least bit impressed…)

When the music is done, Zaroff dispatches Eve and Rainsford rather peremptorily to bed—with Eve making certain that Rainsford understands the unnaturalness of this, too. When they are gone, Zaroff invites Martin to see his trophy-room…

In the middle of the night, Eve wakes Rainsford and tells him that Martin is not in his room. Rainsford is sceptical about Eve’s fears, but agrees to dress and come downstairs with her. They find the hall deserted, and make their way apprehensively into the Count’s trophy-room—where they find answers to all their questions…

The Most Dangerous Game was a pre-Code film, of course, and it took advantage of the era’s relative permissiveness in a number of different ways—not least, in offering for our delectation the screen’s first ever piece of graphic body-horror.

As Eve and Rainsford make their way cautiously into the darkened room, peering around by candle-light, they are confronted by a shocking sight: a human head, mounted on the wall like any other hunting trophy. And it is not the only one… And even worse is to follow: hearing Zaroff coming, the intruders rush into the shadows to hide—with Eve bumping into a huge clear jar in which floats yet another head…pickling.

This sequence is where most of the pre-release cuts to The Most Dangerous Game were made. It was initially much longer, with the trophy-room revealed also to contain intact human bodies which had been stuffed and mounted—and with Zaroff explaining in detail just how the individuals in question died. (The film-makers also went to the trouble of finding out just how you’d go about pickling a head!) This proved too much for test audiences, many of whom walked out. The producers took the hint and cut the sequence right back—while still keeping sufficient evidence of the nature of Zaroff’s madness.

Zaroff enters the trophy-room with Ivan, and also accompanied by two more of his servants, who are carrying a stretcher on which lies a shrouded figure. This brings Eve and Rainsford out of hiding; and, as the former demands wildly to know where her brother is, Rainsford lifts one corner of the sheet…

Both intruders are seized at Zaroff’s command. Rainsford is held by the servants until he is secured via a chain-belt and shackles; while Eve is carried away, struggling and screaming…

The Most Dangerous Game is a perverse glitch in the career of Fay Wray, since it places her in a series of situations in which, for her own safety, her character cannot scream! She doesn’t even do so when confronted by the human heads, but manages to restrain herself to involuntary gasps; and this will be the case later in the film, too. Of course we have to remember that this was Fay’s first genre film, and that she had not yet garnered a reputation as the screen’s premier screamer; yet it is hard to shake the feeling – particularly since Eve is later shown at (relative) liberty – that this little scene was included specifically so that we could have at least one instance of an uninhibited Fay.

As with the earlier scene in which Zaroff described his passion for hunting and his cure for boredom, the confrontation between Zaroff and Rainsford which follows the revelation of the trophy-room reproduces much of the short story’s dialogue. There is an additional resonance here, however, because of the film’s opening scenes on the yacht, in which Rainsford’s beliefs about his profession are questioned. At the very outset we see that Rainsford has never really thought through the implications of his choices; and whatever he might say when unchallenged – as in the books that Zaroff quotes from – when called to account he first retreats into a mixture of evasion and joking, and then takes a stance that is no answer, but instead a smug assumption of privilege.

And if Rainsford is unable to stand up even under Doc’s off-the-cuff cross-questioning, he is utterly unprepared to deal with what Zaroff throws at him.

One of the most unexpected things about The Most Dangerous Game is the degree to which it makes it possible for the viewer to sympathise with Zaroff’s position, in theory, if not in practice; though it probably helps to be as biased against Rainsford as I am. In this lies the true significance of those opening scenes. Zaroff may be a madman, but he knows what he does and why he does it; his detailed self-analysis is in stark contrast to Rainsford’s evident failure to think at all.

If today our unavoidable foreknowledge of this story’s premise takes away from the film’s shock value, it also allows us to appreciate from the very beginning that Zaroff’s interaction with Rainsford is a kind of seduction—a delicate attempt to win him to his own point of view.

Knowing him only from his books, Zaroff has hoped to find in Rainsford a companion, an equal—not merely in the hunt, but intellectually. Of course he is doomed to disappointment. One of this film’s most striking shots is a close-up of Zaroff, a profound sadness coming into his eyes as his glorious dream is shattered; as he absorbs the fact that his “celebrity crush” is in fact a thoroughly conventional, thoroughly unimaginative individual.

But between his own warped philosophy and his vision of a partnership with Rainsford, it is some time before Zaroff grasps this unwelcome truth. Thus, when Rainsford denounces his killing of Martin, Zaroff defends himself not on simple moral grounds, but by insisting that Martin was perfectly sober and fit for the hunt—a visit to the trophy-room tending to have that effect on people. So it was a fair fight, if a swift and unsatisfactory one.

Describing Martin’s blundering efforts, Zaroff fully expects Rainsford to commiserate with him—as a hunter—as he does that he will appreciate that he, Zaroff, strives to bring “the game” into fit condition to be hunted, by providing good food and exercise; and that he gives his quarry weapons and a head start. And if that quarry manages to evade him between midnight and dawn, the prize will be life and freedom. What could possibly be fairer than that?

And even at this point, his protests and insults notwithstanding, Zaroff believes that Rainsford must see his side of the matter; must be thrilled by the possibility of such a hunt, against such a prey. We recall that Rainsford has described hunting as “a game”, and now Zaroff turns his own words back on him:

Zaroff: “Oh, Rainsford! – you’ll find this game worth playing! When the next ship arrives, we’ll have gorgeous sport together!”

But when it slowly dawns upon him that Rainsford means what he says and will not budge, Zaroff passes through sadness to anger. If Rainsford will not hunt with him, well…

It is Zaroff’s practice to give his prey a day’s head start – he made an exception with Martin, because he was so damn annoying – and to hunt in the dark, thus giving away some of his own advantage. It is now dawn: he will therefore send Rainsford out as usual; and, come midnight, he, Zaroff, will hunt again…

We are not, of course, supposed truly to sympathise with Zaroff’s position – even if we do get a giddy, guilty thrill out of it – but there is no doubt at all that the film expects us to appreciate the sight of Rainsford getting his moral comeuppance. Zaroff puts it in terms of Rainsford lacking the courage to follow his convictions to their logical conclusion; the viewer is more likely to think in terms of Karma. The man who justified his life as a professional hunter on the specious grounds of his prey’s equal enjoyment, who dismisses killing as a mere game, as sport, is about to find out that it’s not as much fun as he thought, being on the other end of the rifle…

However—it’s not as simple as that. Had The Most Dangerous Game stayed with the short story’s two-person narrative, some of us – okay, me – might have had no problem remaining in Zaroff’s corner. But more is at stake than even the life of one of the two hunters—as is made clear when, just as Rainsford is to set out, Eve bursts through the front doors of the fort. Presumably she has seen through a window what is going on down in the courtyard, and Rainsford confirms her worst fears, that he is to be hunted.

Zaroff protests this wording, describing what is to follow as “outdoor chess”: Rainsford’s brain and craft against his own; winner take all…

In its expansion of its base story, and the character of Zaroff in particular, The Most Dangerous Game takes full advantage of the time of its production, not only presenting its antagonist as a sexual psychopath, but explicitly tying his perverse hobby into his psychopathy. Women as well as men are Zaroff’s prey, as his chilling dismissal of Eve as “the female animal” makes clear; but there is more than one kind of trophy.

In this respect too, in his dealings with Rainsford, Zaroff moves cautiously. He begins by dismissing Martin’s view of things, his placing of wine and women before the hunt; and having won Rainsford’s casual assent to this, he moves on to specifics. Once again he places Rainsford in a class with himself—and, most significantly – and in intriguing contrast to what was said on the yacht – he calls them both “barbarians”, as opposed to the “civilised” Martin.

Rainsford lets Zaroff talk, rather than agreeing, as he progresses from suggesting that “the revels” should follow the hunt, to quoting certain “Ugandi chieftains” and their philosophy: “First hunt the enemy, then the woman”; and he counters Rainsford’s view of this as, “The savages’ idea” with the insistence that it is, “The natural instinct.” Rainsford grows uncomfortable as Zaroff strips away the veil from what he is saying, his linking of killing – and as we know, the killing of men – with sex. For the audience, a second warning bell is sounded in his simultaneous dismissal of women – “Even such a woman as that,” Zaroff says, gesturing at Eve – to the status of a post-hunt amusement—or, as he now makes explicit, a prize.

We are left in no doubt about what will happen to Eve should Zaroff win the hunt—and that Zaroff calls it “love” only makes it worse. Eve has no doubt either—so it is not surprising that she chooses to go with Rainsford rather than wait to learn her fate.

And so the two set out into the jungle, Rainsford armed only with a hunting-knife…

(The Most Dangerous Game manages to have it both ways here, making full use of the horror of Eve’s situation while indulging in a little audience titillation. The screenplay is careful to tell us that Martin and Eve were cast ashore, “With only the clothes on our backs.” Zaroff is able to provide men’s clothes for his “guests”, but not women’s. Eve, therefore, must head into the jungle wearing a flimsy evening-gown, which is progressively torn away during the chase, leaving her in a state of provocative, pre-Code déshabillé.)

Rainsford is confident at the outset: he leads Eve to high ground, so that he can get his bearings, and decide on the most likely way of evading Zaroff for the four hours necessary to save both their lives. But at the highest peak, a crushing blow is in store: the island is tiny; even smaller in practical terms than in actuality, since some of it is all but impassable—such as Fog Hollow, into which Martin apparently stumbled. Rainsford realises immediately that passive evasion will be impossible. If he is to save himself and Eve, he must do as Zaroff has always intended, and engage fully in the hunt…

The chase sequence of The Most Dangerous Game occupies a full third of the film’s brief running-time and is a classic exercise in suspense. During the first phase of the hunt, neither side gains an advantage: Zaroff evades the traps that Rainsford sets for him, while Rainsford and Eve, in turn, evade Zaroff’s attacks—albeit by a hair’s-breadth. And as the night wears on, we note a curious contradiction: instead of appreciating the situation, that he has, at last, met an antagonist fully worthy of his steel, Zaroff begins to grow angry and frustrated. The realisation that his theory of the hunt has become the reality, that he is engaged in exactly what he swore he wanted, a fair fight against an opponent of equal skill, rips away all pretence on his part. The man who started out with a confident smile upon his lips, who sent Rainsford and Eve on their way with a salute and a genial warning about Fog Hollow, no sooner realises that there is a real possibility of him being bested for the first time than he cheats. What else can we call it, when he resorts first to a rifle, and then to a dog-pack, in a game of “outdoor chess”?

And the dog-pack it is that finally gives Zaroff the unfair advantage he needs. As the minutes creep away, towards the dawn that will – or should – win them their lives and their freedom, Rainsford and Eve end up trapped on a high ledge, below a waterfall and above a raging river. Even here, Zaroff dare not follow—but he sends the dogs in. Rainsford manages to dispatch the first, but as he struggles with the second, Zaroff fires his rifle—sending man and beast alike toppling over the edge and down into the waters below…

The triumphant Zaroff then sends his servant to fetch Eve. It is, after all, still one minute before sunrise…

Back at the fortress, Zaroff takes his time, savouring the moment. A bath – a rest – wine – music; then he sends for Eve.

But it isn’t Eve who enters the room. It’s Rainsford—and he has come to kill—and not in self-defence…

Despite – or, perhaps, because of – the conditions and restrictions that attended its production, The Most Dangerous Game is a remarkable little film. Its action-suspense framework and its touches of horror notwithstanding, this is very much a story of ideas: of opposed philosophies; of two men forced to confront the falsity of their declared principles.

In this, the screenplay by James Ashmore Creelman is a legitimate expansion of Richard Connell’s story, cleverly teasing out the themes that Connell only suggested. Even the inclusion of the character of Eve, which we might consider a mere token gesture, serves to illustrate where the path travelled, in the past, by Zaroff and Rainsford alike undergoes a final, irreconcilable divergence, and where the former’s passion crosses the line into obsession.

This overt opposition, between the prosaically American Rainsford and the floridly European Zaroff, is well-supported by the film’s casting. Leslie Banks as Zaroff is deliciously over-the-top; yet it is a performance not without some subtlety, too, nor an undertone of black humour. Banks never loses control: it is the indeed the reasoned way in which Zaroff makes his case to Rainsford in which the horror of the situation lies. In fact, for most of the film it is a little too easy take a twisted pleasure in Zaroff and his warped philosophy—at least until he reveals himself with respect to Eve, and until circumstances and Bob Rainsford combine to prove him a poor loser—or as I should probably say in context, a bad sport.

Joel McCrea, meanwhile, though inevitably he has a lot less to work with, is solid enough as Rainsford; while the film itself puts his good looks and air of affability to interesting use, turning them into something of a smokescreen for the uncomfortable shadings in the character.

As Eve, Fay Wray is unavoidably hindered by the unpalatable fact that the character is, realistically, simply an object for the men to fight over. However, the screenplay does compensate for this somewhat, by showing us that while Rainsford has the practical skills needed to deal with their extraordinary situation, in the broader sense Eve is much smarter than he is. This is evident in how she has observed and correctly interpreted the details of her stay on Zaroff’s island, and manages to conveys the truth to Rainsford even under Zaroff’s eye; all while hiding her knowledge from Zaroff himself. Her quick wits are in striking contrast to Rainsford’s lack of reflection.

While there are many intriguing things about The Most Dangerous Game, perhaps its most notable quality is its moral ambiguity. This is a key-note struck during the opening sequence on the yacht, and it is maintained right up until the closing frames. In fact, the film does exactly what Zaroff accuses Rainsford of failing to do: it follows its convictions to their logical conclusion.

One of the most interesting touches in the film is the contradictory way in which Rainsford is presented to the viewer, with familiar visual and verbal cues which declare him to be, in simplistic terms, “the hero” working against a script that deliberately undermines the very expectations raised. The film’s opening sequence is designed specifically to encourage the viewer to do what Rainsford himself, clearly, has never done: question his own actions.

This, indeed, his confrontation with Zaroff forces him to do—even as it forces him into the construction of a series of man-traps, the necessity of which do not disguise their inherent savagery. And this is not all he will be driven to do… Yet the film far less interested in the line that lies between the hunter of animals and the hunter of men, than in that between the hunter and the non-hunter. Despite Rainsford’s immediate and horrified rejection of Zaroff’s philosophy, the two men are not opposites, but the two sides of the same coin, driven by the same impulses; the same feeling of superiority over their chosen prey.

And it is for this reason that the screenplay cuts the ground from under Zaroff and Rainsford with equal zest. The Most Dangerous Game leaves us, finally, with two indelible images: of the great hunter, the great sportsman, declaring Rainsford the victor in their battle with seeming magnanimity—even as he reaches for a hidden gun; and of Rainsford himself in the grip of exhaustion and terror, after he is treed by Zaroff’s hounds. We could hardly be further away from the self-satisfied young man who started the film by ranking himself amongst the naturally fortunate of the world.

.’

Footnote: If you haven’t read The Most Dangerous Game, you really should—and there’s no excuse not to. It’s been anthologised a million times, and it’s also available free online.

Want a second opinion of The Most Dangerous Game? Visit 1000 Misspent Hours – And Counting.

♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦

This review is part of the B-Masters’ examination of Homo sapiens as big game…

Splendid work, as always. I saw this a few years ago, after many viewings of King Kong over the years, and noticing all the shared elements was fun.

I’ll have to go read the story, per your request, as I have not up to this point.

LikeLike

I read the story in 8th grade, and the ending stayed with me

“En Garde!”

Rainsford decided that it was the most comfortable bed he had ever slept in.

If you think about it, the ending could be suggesting that Rainsford might continue with the game himself.

I also remember Zaroff introducing himself and his servant as Cossacks, and the teacher explaining what Cossacks were. Was that in the movie, or were Cossacks not as significant in 1932 as they were in 1924?

LikeLike

Yes, Zaroff tells Rainsford all about his background, but it isn’t made much of in the fact, more as the reason he started travelling the world outside of Russia (and slaughtering things) at an early age.

LikeLike

Thank you, my dear!

Fay must have gotten very tired of that log… 😀

LikeLike

My first exposure to the story … well, the central idea of the story … was of course in that remarkable episode of “Get Smart”, which not only had all the usual humour of the show but scenes of real tension and excitement (which were not typically features of the show).

Of course the story/movie has influenced us in many ways, not just cinema and TV. Robert Graysmith’s book “Zodiac” has speculation (everything to do with the Zodiac Killer is speculation, of course) that this movie was a formative influence on the serial killer, possibly because it was showing at an arthouse theatre in San Francisco around the time of the first murders. One of his infamous ciphered notes quotes the title.

LikeLike

In the short story, there’s nothing to suggest that Rainsford won’t go straight back to his career of hunting. In the film, I got the strong impression that he wouldn’t have the stomach for it any more. Which is a neat trick to portray…

LikeLike

No, they don’t have the same emphasis—even though the story does start with a version of the same conversation, and the same divvying up of the world into hunters and hunted.

LikeLike

I believe the Centaur kidnapping a woman is an allusion to the legend of Hercules and Deianira – especially as the tapestry pictures te hunter in nothing but a loincloth and a bow. Which may add an interesting if minor subtext.

The centaur attempted to rape Hercule’s new wife Deianeira – it’s what centaurs do. So Hercules shot him. However, Deianeira herself had been far from enthusiastic at being Hercules’ umpteenth wife and when the centaur mumured with his dying breath she should use his blood in a love-potion for Hercules, she believed him. So that when Hercules fell for yet another woman, she slipped him the drug which sent him back on Olympus by a most painful route ( the best-known version being she rubs it into his lionskin so that it burn him like acid while adhering to his skin and cannot be torn off; Hercules ends it by burning himself alive on a mountaintop ).

In the context of the movie, then what ? We have two men fighting for a woman, and blood-crazed Zaroff with his retinue of evil ethnic servants is obviously the centaur here, although he thinks he is Hercules. But the fate of Hercules could breed some caution in the winner of the contest…

LikeLiked by 1 person

I had the same thought as far as what the knocker represented, and honestly I can’t think of anything else it could be.

My recollection is that Nessus’ (the centaur) blood was poisonous because Hercules shot him with one of the arrows he’d dipped into the Hydra’s venom after slaying it. I’ve only seen the version where it was put on his robe and burned him when he put it on, although Deianeira’s complicity varies in the tellings. Not this has anything to do with anything, but it’s a rare chance to talk mythology!

I couldn’t quite get it to gel as far as an allegory to the movie itself — aside from perhaps hunters fighting over a woman, one more forcefully than the other — but you certainly have an interesting take on it.

LikeLike

The Heracles/Nessus/Deianeira myth was the first thing I thought of, too. I think it may just represent the relationship, in Zaroff’s mind, between hunting and sex, with the centaur also representing the beast/man connection, rather than being a detailed allegory of the movie as a whole.

LikeLike

I think Alaric’s is the right reading here: it’s an unnerving allusion involving (as he says) “hunting and sex”, rather than a citing of the specifics of the myth.

LikeLike

“Kill! Then love! When you have known that, you will have known ecstasy!”

Wow. Pre-Code, man.

I’ve seen the MST version of this story, Bloodlust, about a thousand times, and they also get in the pickling bits and the trophy room (squeamishness obviously having gone down a bit in the intervening years), but since the protagonists in that film are simply happy teenagers out for a boat ride who stumble onto the wrong island, it’s clearly lacking the whole “moral ambiguity” edge.

What gets me about the entire “kill, then love!” thing is not only its inherent gruesomeness and misogyny, but your mind inevitably starts, than has to track with horror, what Zaroff’s saying…clearly this is far from the first time he’s enjoyed one and then the other of these savage pleasures; it’s not some new and exciting notion he wants to try with his favorite author/adventure pal, but where he feels superior in experience. Hey, buddy, you haven’t LIVED until you’ve slaughtered a guy and then raped a woman! YIKES. How many times has he done this? If Eve’s the first woman who’s been unlucky enough to wreck on this island, where did he get his previous victims? What happened to them? What kind of arrangement does he have with any local authorities?

LikeLike

Well, the island’s in the middle of nowhere – and the short story certainly mentions false lights to draw ships onto the rocks, though I can’t remember whether that made it into the film.

LikeLike

In the original story, they’re in the Caribbean; the film says “this part of the Pacific”, while Zaroff says the island used to be part of Portuguese colony, which would probably imply somewhere around Indonesia or Malaysia (assuming they had anywhere real in mind).

Zaroff moves the channel markers, which is what the captain thought in the first place, only the owner of the yacht wouldn’t listen.

LikeLike

😀

Presumably this aspect of his hobby started out in the form of a post-hunt carouse with a willing participant, after the killing of an animal, and then – like everything else Zaroff does – that arrangement began to pall.

There is nothing to say one way or the other whether there have been women on the island before. (The lack of women’s clothes is the only hint not; but then, clothing may have been ripped off…) But if he’s wrecking boats indiscriminately, there’s no reason to think there wouldn’t have been, particularly in a “women and children first” culture. (Yikes! – children!?)

The overarching implication is that Zaroff is saving Eve for a special occasion—as dessert after a particularly satisfactory hunt. We assume he was originally intending to share Eve with Rainsford, but when Rainsford won’t play he reassigns her as the prize.

LikeLike

*icy full body shiver*

Ugh, this story does NOT get better as the logic path is followed.

LikeLike

No, it does not.

It’s fascinating to consider, though, that all this extra text and subtext had its origins simply in the usual Hollywood practice of writing a woman into an all-male scenario. I wonder whether the script’s internal insistence on “following your convictions to their logical conclusion” had its origin in external consideration of Eve’s role?

LikeLike

I would think so? Even when I read the original story I caught myself wondering things like how Zaroff got his supplies, if Ivan did ALL the household work or if there were other servants, etc. When he’s dining on fancy dishes at the end I was going who cooked? Who’s doing the dishes? I mean, you could plausibly posit that some of the “lesser specimens” got threatened/broken in as household staff, I suppose, but it wasn’t important to the emotional point of the story.

But when you open up the story past just Zaroff and Rainsford in the film, as the filmmakers did because DUH you need a romance! angle to sell the plot, it’s an exponential expansion, so to speak, of possibilities not just in logistics but in the emotional makeup of the central conceit. Hunting becomes not a solitary pursuit or even a duet, but a choral work.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Though we never know where the island is, there’s a motor-launch and mention of “the mainland”. In the film we see two servants other than Ivan. (And of course it was standard practice not to acknowledge the presence, or even existence, of servants. There could be a dozen more “below stairs” for all we know.)

I think it’s to the film’s credit that it realises there is no room or time for romance; there isn’t even a last-shot clinch, which was almost as enforced as having a female character in the first place. I think it’s fascinating that they made such complex and unnerving use of what could have been just a cliche.

LikeLike

Actually, Max Steiner’s first full-fledged music score was for RKO’s SYMPHONY OF SIX MILLION (1932), which was followed by BIRD OF PARADISE.

LikeLike

Hi, Anthony! My understanding is that while Symphony Of Six Million was produced first, it uses excerpts of pre-existing music in its score; whereas Bird Of Paradise has the first fully original film score. Though of course I might be wrong about that. 🙂

LikeLike

Often times there is debate over “the first” in various aspects of cinematic development. It all depends on the context one is referring to. In terms of the first talkie to utilize music for dramatic underscoring, SYMPHONY OF SIX MILLION is usually cited. Max Steiner, in a taped interview with Tony Thomas, stated that he always thought it put film music “on the map”. However, the mix of Jewish folk songs (even in a leitmotif manner) with Steiner’s own themes keeps it from laying claim to being the first “original” film score. Steiner’s score for BIRD OF PARADISE would best fill that position. Although both BIRD OF PARADISE and THE MOST DANGEROUS GAME predate KING KONG, it is KONG’s score that brought to full fruition what Steiner introduced in the earlier films. It was also the most influential of the early film scores, the one that left no question as to what music can do for sound films.

LikeLike

Thank you for that clarification, that’s really interesting.

LikeLike

I just rewatched this again today (TCM outdid itself this Halloween). You mentioned Rainsford’s unthinking arrogance. It’s demonstrated again, even after he knows what the stakes are. He creates a Malay Death Trap, which he is convinced will stop the count, so he doesn’t try to have a back-up plan. He doesn’t consider that the count knows what to look for.

LikeLike