“What is all this about the dead coming back to life—and having to be killed a second time?

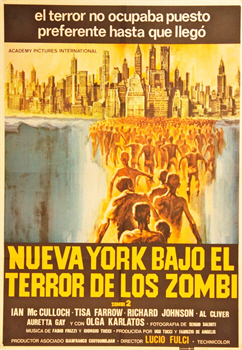

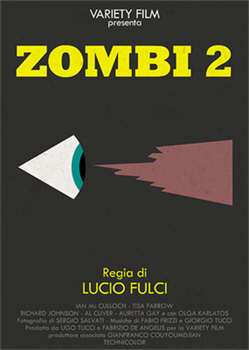

[aka Zombie aka Zombie Flesh Eaters]

Director: Lucio Fulci

Starring: Ian McCulloch, Tisa Farrow, Richard Johnson, Al Cliver (Pier Luigi Conti), Auretta Gay (Auretta Giannone), Stefania D’Amario, Olga Karlatos, Dakar, Lucio Fulci, Franco Fantasia, Ottaviano Dell’Acqua, Ramón Bravo

Screenplay: Elisa Briganti and Dardano Sacchetti (uncredited)

Synopsis: A deserted sailing boat drifts into New York Harbor. Two members of the Harbor Patrol investigate. One searches below deck, finding rotten, abandoned food, signs of a struggle and, in the midst of the devastation, a severed human hand. As the man stares in horror, a huge, shambling figure breaks out of the hold and attacks him, tearing open his throat. It then climbs slowly up onto the deck where, after being shot repeatedly by its victim’s frantic partner, it falls into the water… The story of the boat reaches a local newspaper, whose editor (Lucio Fulci) sends reporter Peter West (Ian McCulloch) to investigate. Questioned by the police, Anne Bowles (Tisa Farrow) identifies the boat as belonging to her father, adding that he set out in it three months earlier, to join some friends in the Antilles. At the morgue, unobserved by the medical examiner preparing to carry out the autopsy, the body of the dead Harbour Patrol officer begins to stir… That night, evading the guard placed upon it, Anne sneaks onto the boat in search of some indication of her father’s fate, only to find Peter there on the same mission—and in possession of a letter written from the island of Matoul. The two agree to join forces. Over the phone, Peter reads the letter from Anne’s father to his editor; it states that the man contracted “a strange disease” and that he believed he would “never leave the island”. Peter persuades his editor to send him and Anne to the Caribbean. Once there, the two ask for help from a holidaying couple, Brian (Al Cliver) and Susan (Auretta Gay). Although Brian warns Peter and Anne that Matoul is spoken of grimly in local legends, he and Susan, having no fixed plans, agree to take them there. Meanwhile, on Matoul itself, Dr Menard (Richard Johnson) tries to call for assistance, but finds that the radio isn’t working. Menard’s wife, Paola (Olga Karlatos), reacts angrily to this, and grows increasingly hysterical when she learns that, “They’ve found another one”. Menard tries to sooth Paola by telling her it was found on the other side of the island, but her only response is to demand to know how soon “they” will reach this side. A violent argument follows, with Paola throwing bitter scorn on her husband’s research and accusing him of being as bad as the local witch-doctors. She begs her husband to get her off the island and, when Menard tells her simply that such a thing is impossible, cries passionately that she hates him. Unswayed by either his wife’s pleading or her abuse, Menard heads for the hospital, where he draws his own blood for use in his experiments… Out on the water, Brian anchors the boat so that Susan can go scuba-diving. As she swims amongst the coral reefs, Susan is frightened by the sudden appearance of a large tiger shark, and drops to the bottom in order to avoid it. Then, as Susan watches in trepidation the movements of the shark, a hand closes upon her shoulder…

Comments: Gather around, children: it’s time for a Shameful Confession.

Until today, I had never seen an Italian zombie movie.

As any regular visitor to this site would know—I’m anal. In fact (not to put too fine a point upon the matter), I’m so very anal, I could have auditioned for the lead role in Rectuma. In practical terms, this means that although I have long had a passionate interest in the Italian zombie movie – that although I own books on the subject – that although my dear friends Keith Allison, Will Laughlin and Scott Ashlin have long drawn me towards it with their sick siren song – I simply could not allow myself to satisfy my craving for this particular sub-genre without starting at the very beginning; that is, with Lucio Fulci’s Zombie.

And what, you might be asking, is the problem with that? Just this—

I have a thing about eye violence.

And on top of that, I have a thing about throat violence. (Although decapitations don’t particularly bother me. Go figure.)

A little knowledge is, as they say, a dangerous thing. In this case, although I didn’t know everything about Zombie, I knew enough to chicken out. Repeatedly. The consequences of this cowardice were, to someone of my straitjacketed habits, pre-determined: no Bruno Mattei for you, young lady, until you finish your Lucio Fulci!

(And so it sat for many months untouched upon my shelf, the Anchor Bay “Walking Dead” Fright Pack; its cellophane wrappers intact; its enclosed security devices unviolated; reproachful; mocking….)

But then we B-Masters decided that we would once again join Nathan Shumate in his annual “Month Of Living Dead”; and I, personally, decided that it was high time I stopped being such a pathetic little panty-waist and faced my demons. And so this morning, clutching a comforting pillow to my chest and drawing a long, nervous breath, I prepared to dip my toes into the murky waters of Lake Fulci.

At this date, I don’t really need to go into the history of Zombie and its title(s), do I? I do? Okay then. Although there still seems to be some dispute about whether or not this film was already in pre-production at the critical moment, it was undoubtedly the enormous success achieved by the re-cut version of Dawn Of The Dead – financed in part by the Argento brothers, Dario and Claudio, and marketed in Italy as Zombi – that paved the way for Lucio Fulci’s distinctive vision of the living dead.

I use the term “distinctive” advisedly. Despite the film’s local release as Zombi 2, only someone who had seen neither film could dismiss Zombie as a rip-off of Dawn Of The Dead. Although certain zombie film ground-rules apply to both, the universes created by George Romero and Lucio Fulci are as disparate philosophically as they are visually—and, in a sense, represent the conceptual divide that lies between the American and the Italian genre film. (Although, I concede, given Romero’s gloomy world view, his films are not necessarily the best illustration of this gap.) While the former tends to favour an eruption of horror into a recognisable reality, and to end, if not with the re-establishment of normality, at least with its protagonists escaping to some version of normality, the latter prefers a progressive shedding of the familiar, the creation of a wholly nightmarish realm of the threatening and illogical, often with no sense of conclusion at all, still less any resumption of “normality”.

Artistically, it is a dangerous predilection, with – as anyone conversant with Italian horror films generally could tell you – infinite scope for failure, but when it works, the results can be sublime. The horror career of Lucio Fulci is a perfect illustration of this. The man had his embarrassments, heaven knows; but his best films are powerful and affecting in a way that many more conventional film-makers can only dream about; a victory of the visceral and the emotional over the reasonable.

In Zombie, however, we have a Lucio Fulci who was just beginning to find his horror voice. This is an uneven work, shot through with all of the flaws that would dog Fulci’s films to a greater or lesser degree for the rest of his career. Its pacing is problematic, although I think at least some of that is intentional; its script is perfunctory at best; and most of its characters might as well be department store dummies.

(That said, they’re a step up from many of their cinematic brethren, inasmuch as no-one is poisonously hateful in personality, nor, upon the whole, suicidally illogical in behaviour.)

But outweighing all of these shortcomings is the sheer impact of the film’s imagery, the combination of Fulci’s direction with the cinematography of Sergio Salvati and the production design of Walter Patriarca—and, of course, the make-up effects of Giannetto De Rossi. This film’s great triumph is the atmosphere it creates once the action shifts to the island of Matoul: the sense of deterioration, of decay, is so palpable you can almost feel it; worse, you can almost smell it. We have no trouble at all believing that in this sick and fetid realm, the very earth might be vomiting up its dead.

As for its zombies— Well, I’m not as well-versed in the zombie film generally as I might be, but as far as I have gone, I can say this: these are the best zombies I have ever seen. The make-up work here is superb, realising in graphic detail every potent human fear of what happens to the body after death. Furthermore, I am of the school that finds the slow, implacable zombie much more frightening than its fast-moving and sentient counterpart, and these are one of the best examples of that, too.

There is, of course, a frank illogicality about the zombie that scuppers films less visually potent than this one. Why should the dead want or need to feed upon the living? – and how could they have the capacity to do so? Why should something so slow, so mindless, so rotten, pose any threat to us at all? Twice in this film, doomed human beings succeed in stripping the rotting flesh right off the bones of their undead attackers, yet cannot fight them off or save themselves. It makes no sense…but then, fear isn’t about things that make sense. No explanation is offered here. Fulci’s zombies are entirely irrational—and effective as hell.

(Of course, if you wanted to get profound about it, you could say that slow zombies act as a perfect metaphor for Death itself: it doesn’t matter how much you try to outrun them – it doesn’t matter how much you think you ought to be able to outrun them – sooner or later – they’re gonna get you…)

In his later and most accomplished works, a confident Fulci dared to have his characters slipping through the cracks in their reality into a terrifying parallel universe that, it seems, always existed just out of their normal range of vision. Here, at the outset of his horror career, his characters voluntarily leave their secure lives and go actively looking for disaster in an obscure corner of the world—and find it.

After an inscrutable opening scene in which a bound and shrouded figure is shot through the head, we cut to New York Harbor, where an apparently abandoned sailing-boat bobs incongruously in the path of the Staten Island ferry. Importantly, Fulci was able to shoot this sequence – and the one that closes the film – on location in New York, and the scenes are all the more evocative for it.

(This opening puts me in mind of the arrival of the ship in Werner Herzog’s version of Nosferatu, which was released early enough in 1979 to perhaps be an influence here.)

Two Harbor Patrol officers board the boat, and one ventures below stairs, where he finds a scene of abandonment and ruin—and, under the fold of a blanket, a severed human hand. The next moment the man is being attacked by a hulking figure that forces him down onto a bunk; as he struggles with it, its flesh tears away in his hand. The attacker bends down and rips the young policeman’s throat open with its teeth.

The bloody-mouthed killer then makes its way up onto the deck. The officer’s partner empties his gun into its chest, propelling it overboard and into the water, where it sinks…

That’s the last we see of our first zombie—but not, we later gather, the last that New York sees of it…

The doings on the boat attract the attention not just of the police, but the press: British ex-pat reporter Peter West is dispatched by his editor (an uncredited Lucio Fulci) to “poke around”. At the now-docked boat, the cops are questioning Anne Bowles, whose father owns the boat; she tells them she hasn’t heard from him in over a month, and hasn’t seen him in over three, since he set out to join friends in the Antilles.

Meanwhile, at the morgue, a medical examiner is establishing to his satisfaction that the dead patrolman suffered massive haemorrhage following a bite. Unfortunately, he then becomes distracted by the poor condition of the instruments which he is offered to perform the autopsy, and consequently fails to notice that, beneath its sheet, the corpse is starting to move…

After this brisk and bloody opening, we hit the stretch of the film that really tests the viewer’s patience, particularly the unnecessarily protracted cute-meet between Anne and Peter. I do think that this tempered pacing was a deliberate choice on Fulci’s part, but it’s hard going, just the same. Anyway, long story short, Peter finds a letter from Anne’s father dated the Caribbean island of Matoul, which states that through his “morbid curiosity” he has contracted “a strange disease”; and that parties unspecified are looking after him as though he were, “Some sort of guinea-pig”.

Peter persuades his editor to send him and Anne to Matoul in search of the solution to the various conundrums that have manifested themselves; a search temporarily derailed by the discovery that Matoul is not marked on any map. Never mind. Having arrived in the Caribbean, Peter and Anne meet a holidaying American couple, Brian and Susan, who, having no fixed plans, agree to help search for the elusive island—even though Brian knows its grim local reputation, and warns Peter in advance that he and Susan won’t be coming ashore when they reach their destination. “I’ve found it never pays to ignore native superstition,” he comments in a display of intelligence unsurpassed in the history of the Italian horror film. Of theoretical intelligence, anyway: when the critical moment comes, Brian will, of course, evince a signal failure to take his own advice.

We then cut to Matoul itself, where the sweaty and unshaven Dr David Menard is trying and failing to make radio contact with someone; anyone…

A scene follows between Menard and his booze-chugging, pill-popping, perpetually hysterical wife, Paola—whose behaviour is perhaps the most rational to be found in the film. Throughout this scene, Fulci repeatedly frames the Menards against the wooden shutters of their villa; he closes it with a close-up of Paola’s eyes…

One of Zombie’s unsolved mysteries is the exact role played by Menard in the events on Matoul. There is a tendency among reviewers to conclude that he is somehow responsible for the raising of the local dead, partly on the basis of Paola’s frenzied accusations, but mostly, I think, because, well, he’s a doctor, he’s scientist, he’s there. On the whole, however, I’m prepared to exonerate Menard of first-cause blame, at least. He strikes me, not so much as someone Meddling In Things That Man Must Leave Alone, but rather as someone who simply cannot accept that there is no scientific basis for what is going on around him; as the kind of arch-rationalist who will continue to scream, “THERE IS A LOGICAL EXPLANATION FOR THIS!!” even as he is having his face eaten off by zombies. It is his inability to accept his own powerlessness that keeps Menard on the island—and hence everyone else along with him; so even if he didn’t cause the crisis, he is responsible for most of what happens.

There is another tendency among reviewers, too, and that is to complain that scuba-diving scenes slow a film down unbearably. Oddly, however, hardly anyone complains about Susan’s scuba-diving scene in Zombie. Possibly, just possibly, her habit of stripping down to a G-string before donning her air-tank and mask has something to do with it.

Me, I can live without the gratuitous nudity; but I admit, I love the direction of this scene: Susan strips off without warning; Peter stares disbelievingly; Anne looks at Susan, then looks at Peter looking at Susan; Peter sees her looking at him looking at Susan and gives her a cheesy grin, but doesn’t stop looking; and Brian, obviously used to Susan’s habits, pays no attention whatsoever.

(The moment that stays with me here is when Susan roughly hikes a tank-strap right up into her barely covered crotch. Male viewers might find it a titillating gesture, but I couldn’t suppress a yelp of sympathetic anguish.)

Susan lets herself down into the water and we share a few lovely scenes of coral and tropical fish before her dive is interrupted by the arrival of…a rather large tiger shark.

Keeping her head, Susan evades the shark by sinking to the bottom and hiding beneath the overhang of a coral outcrop. Sensible girl! As the animal moves temporarily away, Susan heads for the surface to call for help, then sinks again to the bottom to keep out of the shark’s way until the boat draws near. Up above, Brian shoots at the animal but misses (yay!); the shark hits the boat, knocking the three on board to the deck. Susan returns to the safety of her outcrop and is watching the shark warily, when—-

—a hand closes about her shoulder. A rotten hand, belonging to tattered figure in equally tattered clothing…and with no air-tank.

Susan struggles desperately with her slow moving attacker and succeeds in fighting it off by—shoving a piece of seaweed in its face!? (I assume that was meant to be hard coral.) She swims away and hurries to the surface, and then—-

—the zombie grabs and fights with the shark—

—and bites chunks out of it, while itself losing an arm…

Oh. My. God.

It’s an incredible scene. I don’t dispute that.

But—

There is no way that a real tiger shark could have been involved in the creation of such a scene without it having been drugged to the very limits of its endurance. This legendary “fight”, looked at with clear eyes, consists almost entirely of a distressed animal struggling to get away from its tormentor. And that means that while I can appreciate, even admire, the audacity of imagination that not merely conceived of such a scene, but actually went ahead and executed it…I cannot enjoy it.

However—the paucity of footage captured (continuity errors abound here, as they make the most of very little) infers that the shark was still frisky enough for them not to mess with it more than absolutely necessary; and that, in turn, gives me hope that, unlike almost every other animal that ever appeared in an Italian horror film, the shark got out alive.

(And if anyone out there knows differently, please, keep it to yourself. I don’t need to hear about it.)

Leaving this scene and its plethora of unanswered questions – how could a zombie bite through a shark’s skin? what does a zombie taste like? does a shark bitten by a zombie become a zombie shark? do zombie sharks eat other sharks? – we return briefly to Susan – remember Susan? – who tells her incredulous companions that, “There was a man down there!”

We then pay a visit to Menard and the world’s most unnerving hospital—which is a converted church, by the way, and where the “patients” are bound to their beds so tightly, the sheets are soaked with blood. Menard and his nurse are debating what to do about a patient who “won’t last the night”, when they are interrupted by an understandably panicky local, Lucas, who brings ominous news about the natives leaving their village, and what “the new juju man” has been up to. Even at this stage of the game – even doing what he has been doing to “cure” his patients, which we shall shortly witness in flashback – Menard can still spit, “Ridiculous!”

The zombie-shark fight is probably the second most famous scene in the history of the Italian horror film. The most famous one follows fairly hard upon its heels, as night falls, and we re-join Paola Menard, alone at her villa—and in the shower.

(Not content with Auretta Gay’s scuba-diving scene, Fulci here has Olga Karlatos stand in front of one of those triple-angle mirrors, thus giving the viewer front, back and side views simultaneously. Covering all the bases, you might say.)

As Paola lingers in the rushing water, a rotting hand presses itself against the glass of the bathroom window… Contrary to popular rumour, Paola does get dressed after getting out of the shower. She also pops a pill. And then she hears a noise…

Trying to lock herself into an inner room, Paola finds herself unable to shut the door—which is being pushed open from the other side. After a struggle, and some tearing of rotten flesh, Paola manages to get the door closed and locked. But then the zombies start breaking through the flimsy, tropical-climate windows and shutters. Paola tries to build a barricade, but in doing so ventures a little too close to one of the shattered windows. An arm shoots through a jagged opening and grabs Paola by the hair, dragging her slowly, inexorably, towards a jutting shard of wood…face-first…

I can only say again— Oh. My. God.

And, well, I have to be honest: I didn’t quite make it all the way through here. I did try. I looked, and looked away, and looked again; squinted; covered my face; peeked out from behind my pillow, and through my fingers; even resorted to my favourite evasive trick of peering over the top of my glasses, so that everything I did see was blurry. And in the end I saw – well, not all of it, but most of it – and that’s something, right? I mean, I’m not claiming this was an act of moral courage on par with, say, Will Laughlin forcing himself to watch the uncut print of Cannibal Holocaust; but I got further than I ever thought I’d get with it. All in all, I’m not too dissatisfied with myself.

If nothing else, the number of opportunities I had to change my mind about looking or not looking should tell you one salient fact about this notorious scene: it takes for-frickin’-ever to play out. Some people have laughed at the care and deliberation that this supposedly mindless zombie displays in lining his unfortunate victim up with that shard of wood, but I think this was an entirely intentional act on Fulci’s part. Although from Zombie onwards, the eye-gouge would become de rigueur for any self-respecting Italian gut-muncher (and for quite a few with no self-respect whatsoever), when this film was released it had never really been done before; not like this. I think Fulci wanted his audience to sit there and sweat; to mutter, “Oh, they’re not really going to do this. Nah. They’re not. Are they? Surely not. Oh, no. They’re not—are they? Oh, my God! They are! They ARE!! THEY AAAAHHHHHH!!!!”

The eye scene in Zombie would also go on to become one of the jewels in the crown of the whole Video Nasty hysteria, and it isn’t hard to appreciate why. After all, I came to that scene fully prepared, knowing in detail what was going to happen, and exactly how the effect was achieved—and I still couldn’t deal with it. Now, imagine coming to that scene unprepared. Imagine being unsympathetic to horror films, and being forced to watch it. Imagine watching it from a jury-box in an English courtroom at ten o’clock in the morning. It doesn’t excuse what they did…but you do understand the impulse.

The next morning we find Menard displaying his first and only act of sensible behaviour, namely, lying on the beach and getting soused to the gills. He is interrupted in this pursuit by his nurse, who comes to tell him that someone called Matthias is now “one of them” – and to reveal herself as the same kind of pig-headed rationalist as Menard. Menard announces that they have to help Matthias. We shall soon see what this “help” entails.

Meanwhile, the party on the boat have made it to Matoul more or less by accident. With the drive-shaft cracked – a legacy of the collision with the shark – their only choices are to go ashore, or to fire off some flares and hope that someone who can help them responds. The local legends in mind, Brian opts for the latter.

Menard, however, doesn’t notice. He’s busy. Shooting Matthias in the head…

Menard and his nurse, those arch-rationalists, then carry the body out for burial. However, Lucas has observed the flares from the water, and Menard goes to investigate, leaving Lucas and the nurse to finish taking care of business. We get one of my favourite shots in the entire film here, as the camera pulls back to reveal, not just one grave, but a pit full of bodies; all of them bound and shrouded, just like Matthias; all of them shot in the head, just like Matthias… And there’s another pit nearby, already filled in.

Menard collects the visitors from their boat (oh, Brian, Brian, you fool!), and tells Anne about her father. We note, by the way, that Menard’s account, in which Dr Bowles insisted upon staying and being used as a guinea-pig in spite of Menard’s pleas for him to leave Matoul, hardly gels with Bowles’ own account of events in his letter to Anne. Menard’s version has Bowles himself begging for post-death “assistance”, and Menard struggling with himself, only able to shoot when the corpse starts sitting up. And it is this killing, we recognise, that comprises the film’s opening scene.

Although the two versions of this that we see are, suggestively, quite visually distinct, they end in the same way: with Menard saying, “The boat can leave now. Tell the crew.”

Of course, the strange thing is, no-one we know does leave by boat at this point; the only boat is Dr Bowles’ own, which he certainly wasn’t on; yet someone must have been on board—aside from the zombie, that is. I said that I exonerated Menard from creating the zombies, and so I do; but it is pretty clear that there is more going on here than meets the eye (if, under the circumstances, you can excuse that choice of expression). Perhaps Menard, in seeking to understand the local voodoo secrets, unwittingly unleashed this particular plague of zombies. Perhaps he even sent them to New York on purpose. We never know. Menard’s motives remain one of this film’s unexplored ambiguities. All we are sure about is that he is not entirely to be trusted…

From hereon in, Zombie presses its foot hard upon the accelerator, discarding its previously measured pace and barely stopping for breath until its literally apocalyptic climax. Zombie signals its intentions with a justly famous shot: a desolate, wind-swept street; a crab scuttling in the foreground; and in the background, a zombie, large as, um, life; right out there in the open, and no longer politely confining itself to “the other side of the island”.

(And for myself I can say: if I didn’t quite make it through the eye scene, I did manage to watch the rest of Zombie, throat-rippings and all, without once looking away.)

Menard and the visitors arrive at the hospital to be greeted by a garbled message from Lucas about “Mr Fritz”. Menard gives an unconvincing smile and tells the others that his friend, Mr Fritz, has “had an accident”, then asks them to drive on down the road to check on his wife; a belated act of concern that will, of course, reap exactly the reward it deserves.

The friends arrive at the villa to find several zombies chowing down on what’s left of Mrs Menard; two more block their way when they bolt for the exit. Peter and Brian beat these two in the head – note that – and all four of them escape. They pile into Menard’s four-wheel drive – which, unexpectedly, starts the first time – and speed down the road towards the hospital, where a cutaway shows us Menard “helping” Mr Fritz. They never get there, however: a zombie wanders into the road and they hit it at pace.

Remarkably, the driver who panics and hits the accelerator instead of the brake is Brian; and, even more remarkably, the person who ends up with an injured ankle as a result of the ensuing crash is Peter. The four are then forced to walk, and limp, towards the hospital, as the natives’ drums grow ever louder…

Zombie‘s score is another of its strengths. There are indeed native drums a-plenty, and high-pitched electronic whines; but the main score is a piece by Fabio Frizzi and Giorgio Tucci that, perhaps inspired by John Carpenter’s work on Halloween the previous year, is both minimalist and amazingly effective. It does not change with the changing scene, but simply gets louder or softer as events demand.

The four stagger on as far as Peter’s bloody ankle will let them, and then “take five”, with Susan and Brian spying out the land up ahead; a mission that leads to the wholly unwelcome discovery that the spot they have chosen for their rest is an ancient Spanish graveyard full of dead conquistadores.

Oops.

And if we’ve already had the first and second most famous scenes in all Italian zombie movies, here we meet no-one less than the single most famous zombie who, right before Susan’s horrified and disbelieving gaze, proceeds to claw himself up out of the earth. This gentleman, usually referred to affectionately as Ol’ Worm-Eye, would go on to become the poster boy not just for Zombie, but for Italian horror cinema generally.

(And while I haven’t any particular desire to defend Menard, I do feel compelled to observe that if the soil of Matoul is capable of preserving four-hundred-year-dead conquistadores in reasonable working order, well, there’s a lot more going on here than just a little traditional Tampering In God’s Domain.)

Fabulous as this sequence is, on one level it annoys the crap out of me; and since Ol’ Worm-Eye takes his own sweet time about resurrecting himself, I have more than enough time to explain why. There is a little thing, you see, called the “fight-or-flight response”, which is nothing less than a miracle of biological hard-wiring, a way of by-passing that pesky rational side of any human consciousness and insuring that in a crisis situation, we won’t stop to think about it.

Horror films generally underestimate the power of this impulse. It can be overcome, sure, in the face of such things as danger to a loved one; but when it is simply a matter of stay-and-die or run-and-live, that impulse is there to make sure we make the right decision. Which means that, confronted by something that will, certainly, kill you, you don’t just stand there staring at it!! The problem I have here is the same one I have with Lambert’s death in Alien. Sure, I can accept that in the horror of discovering Mrs Menard’s gruesome fate, upon being confronted for the first time with the living dead, these people would just freeze and gawp. But not here, not now; not when they know exactly what the danger is. Basic biology forbids it.

Be that as it may, Susan does just stand there and stare as Ol’ Worm-Eye pulls himself up out of the earth. So it serves her right when, a moment later, he’s biting bloody strips out of her throat.

The reason that Susan is on her own, by the way, is that Peter and Anne, having chosen this of all moments to indulge in a little canoodling, are under attack by undead hands emerging from the ground. Anne’s screams send Brian bolting back down the path, leaving Susan to confront her fate alone. Her screams then bring Peter, Anne and Brian back to the scene just a tad too late. Brian puts two ineffective bullets into Ol’ Worm-Eye’s torso, and then Peter knocks him down with a handy unearthed cross, before using the same item to demolish the zombie’s head. Brian gets no more than a moment’s mourning in before the other two haul him away in the direction of the hospital. Behind them, the soil of the cemetery continues to disgorge its dead…

Hampered by Peter’s injury, the three survivors make it to the hospital just ahead of the hordes of the living dead, which are now converging from all directions. Brian starts putting up barricades as Menard treats Peter’s ankle – which must be the first legitimate piece of doctoring he’s done in who knows how long – and, with a silent grimace, Peter break the news about Paola to Menard.

The zombies begin to press against the hospital – entirely unperturbed, we notice, by the large crosses on the doors – as inside, Menard gives a brief account of the last three months on the island, and the battery of medical tests he used to prove that, There is no such thing as voodooism, dammit!

Menard distributes firearms, and Brian, Lucas and the nurse construct Molotov cocktails using drums of kerosene, as the siege begins in earnest; a sequence made frustrating as hell by the inability of Brian in particular to put two and two together: i.e. head shot = dead zombie, torso shot = live zombie. (What’s worse, although the penny seems to have dropped for Peter, he never says anything.) The zombies prove, as usual, strangely flammable; and for a while the human beings seem to be getting the best of it…except that, busy fighting the zombies pouring in from the outside, they kind of forget about those shrouded figures who were already on the inside…

Finally, only Anne, Peter and Brian are still standing. Outnumbered and hard pressed, they fight their way out of the hospital—only to have Brian fall victim to the classic emotional trap, the loved-one-who-is-now-a-zombie. Proving how well matched a couple they were, he too just stands and stares as zombie Susan looms up before him—and as she bites a chunk out of his arm. Peter puts a bullet through her head, and he and Anne help Brian back to the docks as the hospital goes up in flames behind them…

Of course, Brian’s escape isn’t that easy—and becomes even less so when, ignoring his dying cries that he doesn’t want to become “one of them”, Peter and Anne decide they need him to substantiate their story of what happened on Matoul; and instead of “helping him”, they lock him in the bilge. Anne takes the helm of the boat as Peter fiddles with the radio…and gets New York.

Hey, remember those zombies from the beginning of the film? They’ve been…busy…

The ending of Zombie, although unforgettable, is more like the punchline to a shaggy dog story than one of the truly apocalyptic visions that would conclude Lucio Fulci’s later and more confident works. Fittingly, perhaps: Zombie isn’t by any measure a great film, but it is without question a brutally effective one, a film whose very simplicity gives it a strange power.

Most of its achievement must certainly be laid at the feet of those behind the camera, rather than in front of it—although to be fair, the simple likeability of Ian McCulloch and the baggy-eyed desperation of Richard Johnson do help to carry the film through some of its shakier moments.

The success of Zombie at the box-office ushered in not merely a new phase in the career of Lucio Fulci, but of the Italian horror film in general; a phase that over the next few years would unleash upon the world a cinematic tidal wave of the good, the bad, and the simply unspeakable.

And as for me, well, I’ve done it: I’ve crossed my Rubicon of the undead – near enough, anyway – and now, a whole new realm lies before me. It’s mine, all mine! The taut and brilliant direction of Bruno Mattei and Andrea Bianchi! The skilfully crafted screenplays of Piero Regnoli and Claudio Fragasso! The practical joking zombies! The Oedipal teenage zombies! The zombie animals! The tutu-wearing SWAT guys! The witty reflections on gender! The – the –

I must be out of my fricking mind…

That’s…almost cute…

Footnote: While I don’t hold myself up as an expert, I have at least made some progress in this area since I originally watched Zombie and posted this review—having by this time my own thoughts to offer about tutu-wearing SWAT guys and the wisdom, or otherwise, of taking refuge in a deserted mission during a zombie uprising. If I’ve stalled in this area, it’s because next on my agenda is the Oedipal teenage zombie…

Want a second opinion of Zombie? Visit Braineater and 1000 Misspent Hours – And Counting. (And the Stomp Tokyo one is still out there too, sigh…)

♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦

This review was originally posted as part of MONTH OF THE LIVING DEAD 7.

As long as you are mentioning facing your demons – Bava’s Demons is essentially an Italian zombie movie. In one of my more evil moments I used it to great effect one Halloween. The prior year my brother’s now ex-wife ruined our annual Halloween movie marathon by complaining that the movies (Trick or Treat and others I don’t recall) weren’t scary enough. The next year after I brought over my copy of Demons and Demons 2, she left after the first few minutes of gore.

LikeLike

Seconded. Demons follows the classic “zombie siege” format, with the slight twist that the people are trying to get OUT of the place, rather than keep the monsters out of it. There are a couple of supernatural doings because demons. It’s also quite fun, intentionally and occasionally otherwise, and was one of my original Italian horror movie triumvirate (along with this movie and The Gates of Hell). I haven’t seen the sequel as I’ve been advised it’s the same movie, just not as good, but I imagine I’ll get around to it someday.

LikeLike

Yes, Demons 2 is essentially the exact same movie. The only thing notable a bit unusual I can think of is that other than The Video Dead it may be the only movie with a zombie coming out of a TV.

LikeLike

There’s a big difference between “scary” and “gory”, though! If she’d complained about a lack of gore and then bailed, I’d back you, but that sounds too bait-and-switch for my liking. If someone’s expecting The Haunting Of Hill House, you really shouldn’t show them Dawn Of The Dead. 🙂

LikeLike

She had it coming since our typical Halloween not- scary-enough for her movie choices were more comedy/horror fare. Even Trick Or Treat is rather tame on the scares. At least I think. Skippy from that sitcom and an Ozzy cameo.

But yes, I chose the most over the top gore I could think of that I wanted to watch. I could have brought my copy of Zombi-2 over. My brother had already seen that before he started dating her.

LikeLike

Now that I think about it, The Video Dead was one of the movies that wasn’t scary enough for her….

LikeLike

It actually worse than you think concerning the shark fight. Apparently, it was common practice back then for stunt sharks to be caught, stunned, beached, dried out, and then have all their teeth forcibly removed before they’re returned to the water where they revive for filming. Bill Graefe was notorious for this, as was René Cardona Jr., who was hired on to pull off this stunt but left it to his assistant. If you look close at most of the shots, it may look like teeth are there but trust me, those are just the empty gums.

I go more into this here:

http://microbrewreviews.blogspot.com/2017/10/hubrisween-2017-z-is-for-zombie-1979.html

LikeLike

So what part of “I don’t need to hear about it” did you not understand?? 😕

Yeah, I know they used to do that: I dealt with that practice in the context of Jaws Of Death back in Ye Olde Dayes: just one of many reasons why RC Jr is on my Shit List.

LikeLike

Well, that’s effing horrible.

LikeLike

Could not agree more profoundly.

LikeLike

I watched this today. Love that movie shower. No soap or shampoo, no actual possibility for drying off, and the clothing looks more like a ripped bedsheet than clothes. These are defining characteristics of a movie shower versus a real shower – an excuse for skin to satisfy degenerates like me.

As for the eye scene.

Sadly, I have seen worse. You might be able to take educated guesses, but the excuse for a film is something most people would rather not know about. For those that don’t want to know, that’s the end of the story. For those that might care, a hint. Drug addled celebrity involved.

LikeLike

Fight-or-flight are actually two of four responses to danger! The other two are “freeze” and “fawn”. “Freeze” is an instinctive reaction because lots of predators are more likely to chase movement than to clearly see still prey. And I get that reaction every time I cross the street and see a car coming (and I do mean *every* time), so I find the “frozen still” reaction more believable than you do…

LikeLike

Yeah, but those are add-ons. Everyone gets “fight or flight”, whereas prey animals – that is, animals that know they’re prey, as opposed to human beings in horror movies – get a few more defensive choices. Of course as per your own experiences, humans do sometimes produce those responses too, but not as often as films make out. 🙂

LikeLike

TIL that Olga Karlatos has been a barrister in Bermuda for the past decade. That has no bearing at all upon this movie, of course; I just think it’s kind of cool.

LikeLike

Me too, thanks for that!

(I’ve just been watching her in The Scarlet And The Black.)

LikeLike

Always wondered how the zombie(s)entered Menards house?The front door was clearly locked from the inside when Mrs Menard went to investigate the noises.And within a split second the zombie moved stealthily like a Ninja and blocked the door jamb behind her with his hand.

LikeLike

What happened to the crew of the boat that sailed from Matoul?All we could see were scattered beer cans and lots of fly-infested rotten food on board.Did they jettison after the fatso turned into a zombie?Perhaps the underwater zombie was a crew?

LikeLike

Found the movie scary as hell,had sleepless nights recalling horrific zombie faces.

Logic has never been a strong point in Italian horror flicks,to enjoy them one has to suspend it.

Zombie make up was gruesome but not all that spectacular.Some of the ‘deader’ ones seem to have black eye mascara to effect a missing eye globe.

LikeLike

The scariest moment for me was when the doctor’s wife was stalked by zombies.All we see is a silhouette outside the door reflected on the dressing mirror when she is about to pop her pill.Next thing we know they are in the house,hiding behind the bedroom door.It seems as if they knew their way around and were pretty discreet.Are zombies supposed to be that way?

LikeLike