“You’re going to Camp Blood, aintcha? You’ll never come back again! It’s got a death curse!”

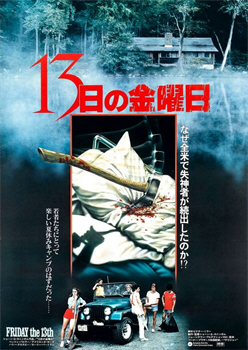

Director: Sean S. Cunningham

Starring: Adrienne King, Betsy Palmer, Harry Crosby, Laurie Bartram, Kevin Bacon, Jeannine Taylor, Mark Nelson, Robbi Morgan, Peter Brouwer, Walt Gorney, Rex Everhart, Ronn Carroll, Ron Millkie

Screenplay: Victor Miller, based upon a story by Sean S. Cunningham and Ron Kurz (uncredited)

Synopsis: Camp Crystal Lake, 1958. After the children are asleep, the camp counsellors have a singalong. Two of them slip away from the group to make out in the barn, but are startled by an intruder. The boy is stabbed to death; the girl backs away, screaming as the killer comes towards her… June, 1980. Annie Phillips (Robbi Morgan) hikes into the small town of Crystal Lake, and enters a diner to ask for directions. The locals are shocked when they hear that the camp near the lake is being re-opened, after the various tragedies; however, a waitress arranges for a truck-driver, Enos (Rex Everhart), to give Annie a lift part of the way. As they head out, Annie and Enos are accosted by the unbalanced Crazy Ralph (Walt Gorney), who warns Annie that if she goes to “Camp Blood”, she will never come back… Though he deplores Ralph’s behaviour, as they drive along Enos reinforces his warning, telling Annie about the various things that have happened at the camp over the years – a child drowned, two counsellors murdered, a series of fires – before urging her to stay away. Annie laughs the warning off, however, and Enos drops her off at a crossroad. Meanwhile, Ned Rubenstein (Mark Nelson) and his friends, Jack Burrell (Kevin Bacon) and Marcie Stanler (Jeannine Taylor), arrive at the camp, where they meet fellow-counsellor, Alice Hardy (Adrienne King), and their new boss, Steve Christy (Peter Brouwer), who immediately sets them to work. As Alice checks with Bill Brown (Harry Crosby) to see what the camp is running short of, Brenda Jones (Laurie Bartram) sets up the archery-range—and gets a shocking introduction to the practical-joking Ned when he shoots an arrow into the target nearest to her. Christy sets off for town in his jeep to collect more supplies, leaving firm instructions for the kids to get as much work done as possible before a looming storm breaks. Out on the road, Annie accepts a lift from someone driving a jeep. She chats happily to the driver until she notices they have passed the turn-off to the camp. When she points this out, the driver speeds up… Frightened, Annie throws herself out of the moving vehicle and runs into the surrounding woods, with the driver in pursuit. Her injured leg slows her down, however; she sobs in terror and despair as the driver pulls a knife… At the camp, a bad-tempered motorcycle cop who, after expressing his suspicion of and dislike for teenagers, informs the counsellors that he is looking for “the town crazy”, last seen heading their way on his bike. And Ralph is closer than anyone suspects: as Alice works in the galley, she is frightened when he suddenly emerges from the pantry, announcing himself “God’s messenger”, and again warning the kids that they are doomed if they stay at the camp… As dusk falls, Jack and Marcie have some private time by the lake, leaving Ned to wander disconsolately away on his own. To his surprise, he sees someone entering one of the outlying cabins, and goes to find out who it is… As the threatened storm begins to break, Alice, Bill and Brenda shelter in the recreation-room; while Jack and Marcie slip into one of the cabins to have sex. So intent are they upon each other that, in the gloom, they do not notice that Ned is lying dead in an upper bunk, his throat cut…

Comments: It is curious to reflect, all these years later, that the entire direction of horror cinema in the 1980s was dictated by a pair of low-budget productions about a killer with a knife.

Nothing exists in isolation, of course; and while Friday The 13th now bears the burden of unleashing the wave of slasher movies that dominated the early 80s, it is evident that it was almost wholly inspired by the unexpected success of Halloween two years before: a film which in turn represents the coming together of several disparate threads of horror-movie development.

While there is a common belief that the slasher movie was “born” in the 1980s, anyone who knows their horror-movie history will be aware that there were proto-slasher films made as early as the 1930s—and even earlier, if you stretch your definition of “slasher film” far enough. The next important nexus formed in the 1960s, when increased social upheaval outside the cinemas, and a breaking-down of the traditional, hampering “standards” on the inside, saw the emergence of a more confronting kind of horror film. 1960 itself saw the almost simultaneous releases of Psycho and Peeping Tom in the US and the UK, respectively, films which not only found major directors dealing in what was, for the time, graphic violence, but also bringing back the sense of aberrant sexuality that had been missing from horror cinema since the censors clamped down on such themes during the 1930s.

But there was an important third player in the game, one which would make this area of film-making its own. In Italy, the style of film known as the giallo was becoming increasingly popular. Having been (inevitably, it seems) pioneered by Mario Bava with his 1963 thriller, La Ragazza che Sapeva Troppo (The Girl Who Knew Too Much / The Evil Eye), the gialli were overtly, like the yellow-jacketed books that inspired them, murder mysteries; but as the 1960s wore on the mystery aspect became more and more perfunctory, with ever-greater emphasis being given to the twisted psychology of the killer—and to the murder scenes themselves. By the time Dario Argento got hold of the giallo, though the mystery of the killer’s identity and motives was still there, the spectacular set-piece murder scenes had not only become the genre’s raison d’être, but were presented in a perversely beautiful way that you can hardly avoid calling “art”.

And meanwhile, there was – of course – Mario Bava, doing everything first and usually best. Bava followed La Ragazza Che Sapeva Troppo with the amusingly frankly titled Sei Donne per l’Assassino (Six Women For The Murderer / Blood And Black Lace), and then spent the rest of the decade playing games with the very conventions he had helped to create: a period of activity that culminated in the absurdly over-the-top Ecologia del Delitto (Ecology Of The Crime / A Bay Of Blood / Twitch Of The Death Nerve), which features no less than thirteen gruesome onscreen deaths, including – note bene – a machete to the face and a young couple jointly impaled with a javelin while having sex. Bava considered the whole thing a huge joke, but not everyone was laughing: his film eventually landed on the British “Video Nasties” list under yet another alternative title, Blood Bath.

Ecologia del Delitto was released in 1971; but it was another three years before the Italian influence began to show itself in the Americas: 1974 offered both The Texas Chainsaw Massacre which, while not a slasher film, does feature a proto-Final Girl sequence; and the Canadian production, Black Christmas, which may be the first genuine example of what we now designate a “slasher movie”. But it would be Halloween, released another four years later, which would prove to be the era’s pivotal film.

Unlike many film-makers working in this area, there is no doubt that John Carpenter knew and admired his Italian predecessors. Their influence is clear enough in Halloween: in the way the film is designed and shot, and chiefly in the bizarre tableau featuring the unfortunate Annie Brackett, laid out with a gravestone at her head, and the scene lit by a jack o’ lantern candle. As with many such moments in the Italian cinema, the scene makes, if not intellectual, then certainly emotional sense, in a manner which is its own justification; ars gratia artis, if you like to put it that way.

But while we can trace John Carpenter’s influences throughout his creation of Halloween, perhaps the most notable thing about Friday The 13th is how it seems to have undergone the opposite process—with anything that might be considered as complicating its scenario stripped ruthlessly away.

At the time of my first viewing of Friday The 13th, many years ago now, I was a slasher movie neophyte—and reacted with a mixture of dismay and disdain to what was unfolding before me: a response provoked chiefly by the realisation that this film existed for no other reason but to show us people dying. There were other reasons for my reaction, too: the lack of characterisation; the emphasis upon gore; and the implications of how the death-scenes were staged. The experience left me repulsed and uncomfortable.

And now— Well, I’m older and, I hope, wiser; certainly better informed; and a little thicker-skinned…perhaps. This time around, somewhat to my surprise, I discovered that Friday The 13th is, if no more complex a film, then still a better piece of film-making than I recognised the first time, and perhaps a smarter one, too; while I was also on firmer ground in judging to what extent the film did – and did not – deserve the accusations that I threw at it the first time around.

Friday The 13th opens at the now-notorious Camp Crystal Lake, in 1958. A couple of young counsellors sneak away from the others, heading to the upper storey of a barn for a little private time. Immediately, the camera assumes a split persona: at times it is objective, but at other moments it is clearly giving us someone’s point-of-view. The latter follows the kids upstairs, surprising them in mid-clinch. As they both adjust their clothing, the boy – who recognises the person who has caught them – begins making an embarrassed apology / excuse. Moments later he falls to the ground, clutching his bloodied abdomen. The girl backs away, screaming, and searching frantically for a way out; but she is trapped…

The narrative then shifts to Friday, 13th June, in “The Present”. While the film was shot in the autumn of 1979 – causing climatic difficulties for its scantily-clad cast-members – it is set at the beginning of the American summer-camp season; and there was, in fact, a Friday the 13th in June of 1980, when the film was released.

A young backpacker called Annie wanders into the small town of Crystal Lake and enters the local diner, looking for directions and hoping for transport information—and a classic “shocked locals” moment ensues, when she asks her way to Camp Crystal Lake:

Local woman: “Camp Blood?”

As a muttered conversation takes place, the head waitress at the diner organises for a trucker-customer, Enos, to give Annie a lift part of the way. Outside, they are immediately accosted by someone who will later be referred to as “the town crazy”, but who horror fans have since taken to their hearts as “Crazy Ralph”.

Alas, like all prophets, Ralph is without honour in his own land; and despite the locals’ own qualms, no-one pays attention to his warnings that Camp Blood has a death-curse on it, or that those venturing there are doomed…

But though he was the first to abuse Ralph, once they’re on the road Enos the trucker concedes that, well, maybe he has a point. Prompted by Annie, he repeats the sad history of Camp Crystal Lake: a young boy drowned in 1957; two counsellors murdered in 1958; a series of fires; and then, when the camp was first set to re-open in 1962, the water going bad for no reason. Enos opines that the place is jinxed, that current owner, Steve Christy, is mad to have sunk $25,000 into fixing the camp up again—and that Annie ought to stay away.

But Annie is unimpressed by “ghost stories”, and has Enos drop her off as planned. He drives off, leaving her to walk the last ten miles…

Another thing that this viewing of Friday The 13th did was settle the nagging question (which came up re: Jason Takes Manhattan, for obvious reasons) of whether these films are actually set in New Jersey, or were only shot there. In fact, the film’s budget didn’t extend to sets. Instead, it uses real locations, and makes no effort to disguise the fact. Camp Crystal Lake itself is played by the real, still-operational Camp NoBeBoSco (where apparently they do not like unauthorised visitors); while the rest of the film was shot in and around Blairstown, Hope and Hardwick, in the north of the state, on sites that in most cases are still extant. (The Blairstown diner, unlike the camp, welcomes film-tourists.)

Thus, Annie jumps out of the truck in front of the Moravian Cemetery in Hope, just at the intersection of Delaware Rd and Mt Hermon Rd; she sets off down the latter…

We then cut to a car on another road—while the twangy banjo music on the soundtrack gives us, perhaps, an exaggerated sense of the horrors to come. It is true that the car carries both Ned, our group’s practical joker, and Jack and Marcie, who give us Friday The 13th’s one on-camera sex-scene; but this film being the ground-breaker that it is, none of these characters are anywhere near as annoying as their slasher-movie progeny would become.

The other point of note here is that Jack is played by a twenty-one-year-old Kevin Bacon, who at this time had only a handful of other screen appearances to his credit. Part of the fun of slasher movies is this chance to catch future stars in an early (and occasionally embarrassing) point in their careers; and though Bacon doesn’t actually embarrass himself, I can’t say we see much from him here that hints at future stardom. For the record, I always thought that Laurie Bartram, who plays Brenda, had the most screen presence amongst the young cast; but as it turns out she never made another movie, so what do I know?

The three new arrivals are barely out of the car before they’re put to work, joining their fellow counsellors / workers, Alice, Bill and Brenda. Alice, who has been fixing up the cabins, then has an acutely uncomfortable encounter with Steve Christy, who makes his personal interest in her only too clear—until Alice begins speaking obliquely of having things to clear up in California, and maybe having to leave, upon which Christy backs off…although not without stroking her hair.

(I was dismayed to learn that, in the minds of the film-makers, there had been a sexual relationship between Alice and Steve Christy prior to the events we witness. I have to say, nothing in their interaction has ever suggested that to me. Rather, I see a young woman trying to find a way of evading the advances of her much-older boss without losing her job—but perhaps that’s just me?)

Escaping, Alice runs down to the dock to check in with Bill, who is doing some painting; and at this point we again realise we are watching her from someone else’s point-of-view…

After giving firm orders about the amount of work he wants done before the developing storm breaks, Christy sets off for town in his jeep. Brenda returns to the archery-range, where she is introduced to Ned Rubenstein’s sense of humour when he shoots an arrow at the target she is standing by. Brenda takes this more lightly than I would, inasmuch as she does not respond by grabbing that arrow and—

Well, never mind. Let’s leave a full consideration of the capabilities of arrows for later in the film.

Meanwhile, out on the road, Annie is hitchhiking. She runs up eagerly when a jeep pulls over, and babbles happily about her plans for the summer to the strangely silent driver – whose face we do not see – until the car shoots past the turn-off to the camp. Annie points this out—but the driver’s only response is to speed up…

Thoroughly frightened, Annie throws herself out of the car. She injures her leg in landing, but nevertheless scrambles up the bank and into the woods. Her desperate bid for escape is doomed from the outset, however, and comes to an end when she trips and falls almost at her pursuer’s feet. Though she sobs and begs for her life, the other’s only response is to take out a knife and cut her throat…

Back at the camp, Steve Christy’s orders are being neglected in favour of swimming and sun-bathing down on the lake—where Ned pulls yet another “hilarious” stunt by pretending to drown; all in order to get mouth-to-mouth, you understand.

And then—

OH NO NO NO NO NO NO NO NO NO!!!!!!!!!!

Look, I appreciate that this is a horror movie…but that doesn’t really excuse the inclusion of footage of a real snake being really killed, even if that did happen on the set (and even with Roger Corman as a model). At this point I can watch everything else that happens in this film, but I cannot watch that.

Ugh.

(Of course this scene establishes the existence of the machete…)

Joker Ned is jumping around in his underwear and a feathered head-dress making “Whoo-whoo!” noises when the camp is visited by a motorcycle cop. Officially he’s there to warn them that Crazy Ralph is in one of his moods, but first he takes time out to express his dislike of teenagers – at this point, we don’t blame him – and his suspicions over what they might be smoking.

The kids are inclined to laugh, but Officer Dorf speaks more truly than they know: while working in the galley, Alice gets the shock of her life – so far – when Ralph suddenly emerges from the pantry, preaching his gospel:

Crazy Ralph: “God sent me! I got to warn ya: you’re doomed if you stay…”

“What next?” demands Alice helplessly, as Ralph departs. Needless to say, she’ll get her answer soon enough…

In the rather beautiful dusk, Jack and Marcie spend some time together, leaving eternal fifth-wheel Ned to wander off on his own. To his surprise and puzzlement, he sees someone slipping into one of the outlying cabins, and goes to investigate.

And that’s the last we see of Ned.

Well. Almost the last…

One thing that Friday The 13th does very well is provide an answer to the eternal slasher-movie question of how these things can be going on without anyone noticing. It helps that the film has a relatively small cast: later ones, in their efforts to ramp up the body-count, write in so many extras that it really does become absurd. Here, with only six kids (the others comment on Annie’s non-appearance, but think no more of it), they separate naturally into smaller groups, before being kept apart by the breaking of a violent rainstorm.

Thus, Alice, Bill and Brenda are in the recreation-room; Jack and Marcie are off in one of the cabins, doing what Jack and Marcie do (so the others leave them to themselves); and – cruelly, but not surprisingly – no-one cares where Ned is. The killer is therefore able to work from the fringes of the group in.

At the same time, Friday The 13th here offers a few shocks that have nothing to do with its lurking killer. I do not refer to the sex-scene between Jack and Marcie (during which we are offered glimpses of Jeannine Taylor’s boobs and Kevin Bacon’s butt), but what the others are up to—Alice in particular.

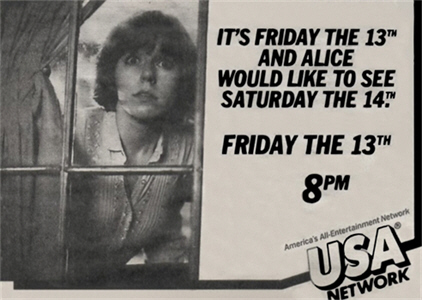

The phenomenon of the Final Girl (to use the term coined by Carol Clover, which has since become part of the bedrock of the pop-cultural world) is, to my way of thinking, the most interesting and worthwhile aspect of the slasher-movie genre. However, like everything else, the Final Girl is a construct which has undergone several cycles of evolution since her creation: the earliest one being, in the face of the critical backlash which occurred in the wake of this film’s release, to be held to an ever-more rigidly imposed moral standard.

It can be startling, therefore, to remember what potential Final Girls could get away with, before the Moral Majority had their say. For example, in Halloween, we have Laurie Strode smoking pot (not well, but she does it); while here, in response to Brenda’s suggestion of a game of “Strip Monopoly”, it is Alice who gets beers for everyone, and Alice who goes to see if there is any of Marcie’s pot left—offering the remark, “I’m not going to pass ‘Go’ without a glow!” This is behaviour that, a year or two later, would mark her for death.

But of course – and even at this early stage of the game – it is sex that actually marks people for death. Post-coitally, Jack and Marcie separate: she slipping on her panties, a t-shirt and a raincoat to venture out through the rain to the bath-house; and he lounging back on the lower bunk. After a few moments, Jack is puzzled when something drips onto him. He hasn’t even had a chance to grasp the fact that’s it’s blood when—

—an arm reaches out from beneath the bed and clamps him down, while an arrow is thrust up through the bed, and then through the base of his throat…

…while Marcie, having made her pit-stop, eventually becomes convinced that she is not alone in the bath-house…and finds out she’s right the hard way, via an axe to the face…

Meanwhile, though Bill sits shirtless and Brenda has been reduced to her underwear, Alice remains fully clad until finally landing on one of Bill’s properties—but a blast from the storm intervenes just as she is about to remove her blouse, blowing open the door and scattering the game’s components all over the floor.

(Speaking of eyebrow-raising touches: Brenda responds to Alice’s aborted strip with, “Just when it was getting interesting…”)

This brings things to a halt. Worried that she left her cabin windows open, Brenda throws a hooded slicker over her underwear and takes off into the night; while Bill and Alice tidy up.

The long-absent Steve Christy finishes up a belated meal at a local diner before heading back to camp. He is only halfway there when his jeep breaks down, but he is fortunate enough to flag down a passing police-car. It is carrying, not our acquaintance, Officer Dorf, but his superior, Sergeant Tierney, who gives Steve a lift.

Brenda is lying in bed reading when she hears what sounds to her like a child crying for help. The plea becomes more urgent, enough so that, collecting a torch, Brenda ventures out into the rain, seeking the source of the cries. She has followed them onto the archery-range when suddenly, overhead lights flood the area, illuminating and isolating her; making her the perfect target…

When Bill returns from checking the generator, a nervous Alice confesses to him that she thought she heard a scream; though she admits it was probably only the storm. Bill offers to check on Brenda, and Alice decides to tag along. When they don’t find her in her cabin, they conclude easily enough that she is with Jack and Marcie—until Bill notices an axe lying in Brenda’s bed…

Thoroughly unnerved now, Bill and Alice go looking for the others, but can’t find any of them. Bill is still prepared to believe that the two of them are the targets of a joke, but Alice insists upon calling outside the camp for help. They have to break into the office – it turns out to be about the only door in the whole place that can be, and is, locked – but having done so, they discover that the phone isn’t working.

And nor can they get Ned’s car started.

By now, Alice is freaked out enough to suggest hiking out; but Bill points out that it’s ten miles even to the crossroads, and counter-argues that they wait for Steve. They will then be able to use his jeep if they decide they really do need to leave.

Speaking of Steve— When Sergeant Tierney is called to a car-crash in the opposite direction, he drops off his passenger short of the camp. Steve walks the rest of the way, and has just reached the camp’s entrance sign when he is blinded by the flash of a torch. However, when his vision clears, he recognises the person holding it…

At the camp, Alice has calmed down sufficiently to doze off on the sofa; so she doesn’t notice when the lights go out. Assuming that the generator has broken down or run out of gas, Bill takes a lantern and ventures out on his own…

Some time later, Alice jerks awake to find herself on her own and in the dark. Too nervous to stay alone, she heads out looking for Bill, guessing that she might find him at the power-house.

And she does, too: impaled to the door with a trio of arrows – one through his groin – and with his throat slashed…

Screaming in horror, Alice flees back to the recreation-room—but there’s no lock on the door—and it opens outwards. Without hesitation, she constructs a makeshift barricade, holding the door shut via a rope lopped over a ceiling-beam, and piling furniture up against it.

Then, arming herself with a baseball bat, she retreats into the galley, where she allows herself to relax and catch her breath…

…until Brenda’s battered and bloodied body is tossed through a window.

Alice is still dealing with this shock when car headlights flash outside. Seeing a blue jeep pull up, she gives a sob of relief and tears down her barricade so that she can rush out.

But the newcomer is not Steve Christy, as she assumed. It’s a stranger; a woman…

The fact that the killer in Friday The 13th is a woman – and a middle-aged woman at that – was certainly one of the film-makers’ best ideas…except for the manner in which Pamela Voorhees is introduced. Her first appearance, occurring so late in the film, erases the possibility that she could be anyone but the killer, and so wastes a great deal of the potential surprise and shock-value.

(I take issue with the film-makers’ chortling over having “fooled” their audience. No such thing: when Annie is killed early on, naturally we’re not shown the killer’s face; but we do see the hand with which the knife is being wielded, and it is a man’s. [In fact, that of Tom Savini’s assistant, Taso Stavrakis.] And this is also true during the killing of Jack. You don’t put that in front of your viewers and then claim to have fooled them!)

And it’s all the more disappointing when you consider that Friday The 13th is, in effect, structured like a murder mystery; or, perhaps more correctly, like a giallo. The vast majority of gialli keep the “whodunit” framework of the classic mystery story, even while ramping up the sex and violence; but whereas those films provide a raft of suspects for the viewer to choose from, hiding their killers amongst their red herrings, Friday The 13th offers nothing but red herrings – Crazy Ralph, Enos the trucker, Steve Christy, Officer Dorf – and then reveals its killer as a hitherto unknown character.

It’s unforgivable, really—both in its violation of the tacit contract existing between film-maker and viewer, and because it would have been so easy to establish Pamela as a local figure in the early scenes. She could, for instance, have entered the diner when Annie was there—causing a traditional “sudden silence” amongst the locals, since she was so tragically enmeshed in the history of Camp Crystal Lake; or, since we’re told she works for the Christys, we could have seen her delivering supplies to the camp. Anything to establish in both Alice’s mind and the viewer’s not just the fact of her existence, but her right to be on the premises.

And there’s another way in which this could have strengthened the film. When I mentioned at the outset that perhaps Friday the 13th was a bit smarter than I’d previously recognised, I was referring obliquely to the handling of the lead-up to Annie’s death, and the avidity with which she jumps into the car that pulls up for her, and subsequently chats about ”the kids”—which suggests – doesn’t it? – that the driver is a woman. Sure, attitudes to hitchhiking were different back then; and sure, Annie has already accepted a lift from Enos; but Enos was vouched for by the people at the diner, not a “cold” pick-up like this one. And how much more sense would it make if the driver was not just a woman, but someone Annie recognises—and, perhaps, knows is connected with the camp?

Furthermore, such a pre-establishment of Pamela would have gone some considerable way to excusing Alice’s tearing down of her barricade which, as things stand, is one of the few criticisms I have to make of this film’s Final Girl sequence. It’s a pretty serious criticism, though, because even if she did think it was Steve Christy out there, that is no reason for her to drop her defences. In fact, very much to the contrary.

Be that as it may, when a blue jeep drives up Alice does pull away the items blocking the door and rush outside—only to stop short at the sight of a stranger:

Alice: “Who are you!?”

Pamela: “Why, I’m Mrs Voorhees.”

Believing that help has arrived, Alice all but collapses in Mrs Voorhees’ arms. She breaks into a panicked version of the night’s events, but then grows frustrated with the calm way in which the newcomer receives her story, and her apparent refusal to understand that they may both be in imminent danger. Instead, Mrs Voorhees insists upon seeing for herself what has been going on, and strides into the recreation-room with an apprehensive Alice in her wake.

But she is properly shocked by the sight of Brenda’s body lying on the galley floor. “Oh, God, this place,” she whispers, speaking bitterly of “all the trouble” there has been at the camp over the years, and how Steve Christy should never have tried to re-open it…

Mrs Voorhees goes on to speak of the young boy who was drowned so many years ago; who died because the counsellors weren’t paying sufficient attention:

Pamela: “His name was Jason…”

As she speaks, losing herself in the story of the boy’s tragic death, Alice grows increasingly frightened and begins to back away. Mrs Voorhees comes after her, however, grasping her by the shoulders and shaking her as she insists that Jason should have been watched, every moment: “Jason was—”

She stops herself; but we have no doubt that the word trembling on her lips was “special”.

As Alice stares in horrified comprehension, Mrs Voorhees continues to speak of Jason – her son – her only child – whose birthday it is – and how she simply couldn’t let them open the camp again. In her mind, Jason begins to speak to her, and she to him; and when she turns once more upon Alice, her confusion over the two time periods is complete. Pulling a hunting-knife from its sheath, she snarls at Alice: “You should have been paying attention!”

As with many “firsts”, Friday The 13th frequently deviates from what we now consider the rules of its genre; rules which it only began to lay down, but which did not take solid form for some time, and a number of films, later: Alice’s behavioural transgressions being the most obvious instance. We recognise this as we watch, even as we develop a sort of “split-vision”, which acknowledges the proper positioning of a particular film in its historical timeline.

Films exist in a world where films exist, of course—which effects the degree of ignorance or naivety acceptable in film characters. You cannot, for example, get away these days with making a zombie film in which the characters don’t know what a zombie is, or how to recognise one: they might discover that things don’t work like they do in the movies; but still there has to be a moment of recognition, and one not too long delayed.

And likewise, Final Girls now exist in a world where everyone knows that there are things you do and do not do—and a contemporary Final Girl who puts her weapon down after an apparently successful kill, or who throws her arms around someone she knows who has turned up out of the blue, can expect only unsympathetic jeering from the audience.

But conversely, when it comes to the early Final Girls – who did not have their sisters’ wealth of experience to draw upon – we tend to make allowances. Thus, we wince when Laurie Strode drops her knife, or when Alice tears down her barricade—but it’s not a deal-breaker. They just didn’t know any better.

And it is for this reason that I am also able to overlook Alice’s main failing as a Final Girl: her refusal to finish Pamela Voorhees off when she has the chance—which she does twice.

Still— I guess it’s one thing if you’re fighting an undead killer, or even an apparently human but nevertheless unstoppable psycho; it’s another if, like Alice, you’re confronted with a woman twice your age who is a bereaved mother, to boot. Add to that a simple reluctance to kill, and her hesitancy is understandable if not particularly wise.

But there is a significant upside to Alice’s lack of killer instinct, namely that it lays the platform for one of the best-sustained and most suspenseful of all the Final Girl sequences. For a full seventeen minutes the climactic battle is waged, with the balance of power tipping first one way and then the other, and a nice mix of evasion and fighting.

What stands out about Alice is that she is never passive: from the moment she discovers Bill’s body and grasps what’s at stake, she is at high-alert and on the move, seeking to protect herself using whatever means come to hand, and working her way through an amusing variety of makeshift weapons (she does some serious damage with a frying-pan). She makes mistakes, of course, and there is some hiding, and some whimpering; but when push comes to shove Alice shows herself willing not only to defend herself, but to go on the attack, too; and despite her reluctance to take a life, when she finally accepts that this is the only way she can save herself – and when she gets her hands on that machete – she doesn’t mess around…

The climax of Friday the 13th is surely one of the most famous scenes in slasher-movie history; but an even more famous one follows it, as a physically and emotionally exhausted Alice drifts upon the lake in one of the camp’s canoes—and then discovers that she is not alone…

Ironically, it seems that it was not Tom Savini’s bloody handiwork but this now-famous jump-scare that made up the minds of the Paramount executives: it was when they observed the effect of this kicker-scene upon test audiences that they made the daring – and, in many eyes, shameful – decision to pick up the distribution rights to Friday the 13th and put it into wide release. Discovering quickly that it had a minor goldmine on their hands, Paramount simply shrugged off the first wave of criticism levelled at it—much of which, we should note, came from the studios which had lost the bidding war for the film, most prominently Warners…which now owns the rights to the Friday The 13th franchise, and has made a tidy sum via its DVD releases.

But it is doubtful that Paramount was prepared for the storm which subsequently broke, with Friday The 13th becoming the target of hysterical denunciation by critics, morals crusaders, parent groups, and anyone else with an axe to grind (if you’ll pardon the expression). The charge was led by Gene Siskel and Roger Ebert who, in their campaign against the film, unbelievably went so far as to publicise the home addresses of Sean Cunningham and Betsy Palmer, effectively encouraging people to harass them. (Ebert should have remembered that, in 1968, he similarly denounced Night Of The Living Dead…)

A point now often overlooked (or at least, retconned) is that, upon first encounter, the MPAA didn’t have much of a problem with Friday The 13th. The organisation did insist upon some cutting of its bloody effects before they issued a seal; but there is nothing to indicate that those responsible for passing the film for general release anticipated the magnitude of the blowback which would follow—nor that much of it would be directed at themselves, for allowing “this disgraceful excuse for a film” into cinemas.

The MPAA was not slow to take the hint, however; and it made up for its original lapse in judgement by waging an ever-more punitive war against the wave of slasher movies that, inevitably, were put into production in the wake of Friday The 13th and its almost absurd financial success. Indeed, the realisation that a film made cheaply and quickly, with no stars to speak of, just some gruesome makeup effects, could nevertheless turn a significant profit resulted in a literal deluge of further slasher movies: so many, so fast – all of them doing their bit to lock in the rules of the genre – that it was a mere fourteen months after the release of Friday The 13th itself that the first parody of the genre appeared.

But that’s another story.

Re-watching Friday The 13th at this distance, will all these points in mind, perhaps the most shocking thing about it is how inoffensive it now seems. The kill-scenes still have their impact in context, but in light of what is now possible, and considered permissible, they’re almost quaint.

The other shocking thing is the discovery that this is on the whole a competent piece of film-making; occasionally more so, particularly with respect to the cinematography of Barry Abrams, who makes good and spooky use of the rural setting and achieves a number of striking compositions.

(Speaking of which— I was more than a little startled by one shot of Pamela Voorhees, framed through the gap she has just hacked in the wooden pantry door: this, a full year before the now-iconic shot of Jack Nicholson in The Shining! Of course given Stanley Kubrick’s glacier-paced working methods, it’s possible that this is another example of a low-budget copyist getting to cinemas first; but still, it gave me a jolt.)

And of course, Friday The 13th wouldn’t be the film it is without the score of Harry Manfredini…of whom it might almost be said, he built a career on eight notes: his chh-chh-chh-chh-hah-hah-hah-hah holds its own in the ranks of the most instantly identifiable film motifs; while the rest of his work, though less memorable, well supports the action. This is also a film that knows how to use silences and ambient noise.

Friday The 13th has its crudities, and its absurdities, and its moments of poor taste; but there’s no question that it gains markedly by the accidental expedient of being first. This is particularly so with respect to its handling of its characters: not only are there a reasonable (and practical) number of them, the film even goes to the trouble of fleshing them out a little.

Jack and Marcie, for instance, though their main function is to provide the film’s sex-scene, are shown as having a relationship that is emotional as well as physical. Ned is an idiot, granted; but he’s also kind of pathetic; and if Bill has no discernible personality, we can’t say he’s annoying; while we’re given sufficient reason to like Brenda and Alice. The acting likewise is generally competent; while the off-kilter performance of Betsy Palmer, cast perhaps as much against type as anyone ever was, is genuinely memorable.

Though her ability to be always exactly where she needs to be raises eyebrows, we can’t really accuse Pamela Voorhees of Offscreen Teleportation©, later such a hallmark of the genre; although her choosing just the right bed, at just the right time, is more than a little ridiculous. Most of her kills (and her killing, too), are straightforward and gruesome. The disposal of Jack is an obvious exception; but despite the open invitation to ponder that kill’s myriad improbabilities – how exactly do you get sufficient upswing while lying under a bed? – it is the more understated logistics of Bill’s dangling death that truly boggle the mind.

But the reality of slasher movies, this one included, is that most of them don’t have a plot so much as an excuse; and Friday The 13th employed its tropes so efficiently, it really left its imitators with little else to do but exaggerate: more nudity, more violence, increasingly bizarre kill-scenes, a much-higher body-count. At the same time, any pretence that these films existed for any reason but their nudity and violence was quickly dropped, with numerous minor characters introduced for no reason other than to take off their clothes and die. Moreover – whether intentionally, so as not to make people feel bad over their gruesome fates, or just because of poor writing – the main characters in many instances were actively hateful, making the films an endurance test and pushing the audience into siding with the killer.

And with this exaggeration of their framework, it became harder to overlook or to excuse certain aspects of these films.

I may say that I consider both of the main criticisms that tend to be levelled at slasher movies rather absurd: first, that the use of a POV shot is to encourage the viewer to identify with the killer; and second, that they carry a conscious have-sex-and-die message.

The first criticism is easily disposed of: the POV shot has nothing to do with identification, and everything to do with hiding the killer’s identity, where it is necessary to do so. This is the also the reason why, in Italian films, the killer always wears black gloves, so that we can’t see their hands (Sean Cunningham & Co. should have paid heed). In any case, this is a criticism that hardly applies in this instance, as this is almost the only time in the franchise when this tactic is deployed. Having lifted this, like so much, from the gialli – by way of the indelible opening minutes of Halloween – the Friday The 13th films subsequently dropped the murder-mystery set-up, all but in the ludicrously misguided A New Beginning, giving us instead Jason Voorhees right out there in the open.

As for the second, though it is not difficult to see why such a charge should be made, it is again a matter of over-interpretation. The reality is that slasher movies basically exist to show the viewer boobs and blood, and what simpler way of offering both than by following a sex-scene with a kill-scene? We should also consider that these films are aimed predominantly at a young audience—so why on earth would anyone want to insert a buzz-kill message like that?

That said— There is something insidious operating here that needs to be addressed.

While the accusations of misogyny levelled at the slasher-movie genre are, for the most part, misguided – for the most part: there are certainly exceptions – there is no question that there is a disparity in the way that boys and girls are treated in their respective kill-scenes, which may be summed up thus: boys die in shock moments, girls get stalked.

As with everything else, this is less prominent in Friday The 13th than in many similar films; but it is nevertheless there. The opening double-murder illustrates the point exactly: the boy is attacked quickly and collapses; the POV shot then follows the girl as she backs away in terror, making futile efforts to find either a way out or somewhere to hide; and the camera freezes on her screaming face as she realises that she is going to die…

The film proper follows the same pattern. We do not see either Ned or Bill die: instead, we are shown Ned’s body after the event, and follow Alice as she discovers Bill’s. Only Jack dies on-camera…and that (yes, okay) is because he’s just had sex.

We do not witness Brenda’s death either, but she is treated as the girl counsellor is, with the camera showing us her fear as she recognises that she in danger. With both Annie and Marcie, however, we watch from start to finish, every disturbing moment, as the killer singles them out, pursues them, terrorises them, and slaughters them. Annie’s death scene occupies a full two minutes of screentime, from the moment in the car when she realises something is wrong, to the moment when she has her throat cut. Marcie’s death is even more drawn out: between her realising that she is not alone in the bath-house to taking an axe between the eyes, almost two-and-a-half minutes pass.

And there is something else we need to note about Marcie: the way she is dressed, in panties and a short t-shirt that doesn’t cover them.

This is where I have an issue with slasher movies, occasionally to the point of being genuinely offended: their tendency, not just to have girls naked or in skimpy clothing when they die, which bad enough, but to have the camera leer at their bodies while the killer is closing in; sexualising the moment of death, and turning mortal terror into a peep-show.

And this is where we might be inclined to concede that the have-sex-and-die brigade have a point: not in the fact of it, but in the way in which these scenes play out; because if boys and girls alike die after having sex, the latter almost invariably get the worst of it.

And yet, as I say, on the whole I reject the charge of misogyny brought against the slasher genre. Rather, I’d almost call these films misandrous—because in the world of the slasher movie, it the girls we ultimately remember, the boys who are truly disposable; who exist for no reason but to allow the film’s special-effects maven to practice his art.

Which brings us to the slasher movie’s one great justification: the Final Girl.

Over time there would be attempts to give us Final Boys, and recently there has been a shift towards Final Couples; but I doubt think there’s any question that the most effective slasher movies are those which ultimately pit their killer against the last girl standing.

For some viewers, slasher movies are all about the kills; but for me, it’s all about this: the pleasure of watching an essentially ordinary human being stand up in the face of an appalling threat and, through a combination of courage and ingenuity, survive. No film genre that gives us that can be entirely without merit.

Footnote: I have a side-project in mind with respect to this film and its ilk; watch this space!…

…and ETA: Revising my original review of Friday The 13th has given me an excuse to introduce a much-pondered new feature, Ranking The Final Girls.

Want a second opinion of Friday the 13th? Visit 1000 Misspent Hours – And Counting.

I didn’t see any of the F13 movies until around 1987, when our local channel had showed all them (so far), one each night for a week around Halloween. You could definitely notice the drop in quality from one night to the next.

I remember my roommate at the time (a rather demure middle-aged lady) sitting down each evening to watch them after they had started. I kept telling her each night, “You might not want to watch this”, and her saying, “Oh, I can handle it”. She left earlier and earlier each evening.

I always thought the musical sting was actually saying, “Ja-Ja-Ja-Ja-son-son-son-son”. Of course, by the time I saw the movies, it was quite clear just who Jason was, so I might have been hearing things.

LikeLike

It does say “Jason” sometimes, but not until they’ve pulled the most outrageous retcon in film history. 🙂

I hadn’t seen any of them until I sat down to do this sweep the first time, and at that time my access was via grimy VHS and/or cut TV prints. I can appreciate now the manoeuvring of the first four, and get some amusement out of the increasing desperation of the rest.

LikeLike

I really enjoy the first wave of slashers post-Halloween because there was an effort to make them a whodunit before it became increasingly about howtheydunit, motives be damned, and characters got so stupid how could you not start rooting for the Freddies and Jasons of the world. My Bloody Valentine is an apex example of why I love these things. Great read as always.

LikeLike

Thank you!

Yes, it’s odd, because the two dominant franchises didn’t bother with it after this; I suppose the rest felt they had to find a different hook. So to speak.

I think My Bloody Valentine is actually a pretty good film, not just slasher movie. I’ll be copying it over at some point, though I have to decide whether this time around I’m going to try and get hold of the restored version (I own the original cut version).

LikeLike

I would recommend the upgrade for two reasons. One, yes, it does add back in a lot of excised grue but it also restores a lot of the murder set-pieces to their original edits and makes things far less jarring and far more harrowing. And two, and more importantly, the scenes in the mine look sooooooooooo much better, cleaner, discernible. It truly is like watching it again for the first time. I upgraded when I tackled the movie for an O, Cananda Blogathon I participated in earlier this year, which was a ton of fun getting into the guts of Dunning, Link and Cinépix.

LikeLike

Noted, thank you. It’s available for DVD rental here, I believe.

I really should get out more and weasel my way into a few Blogathons…

LikeLike

I have been in the proximity of Kane Hodder, but not being a huge Friday fan had nothing to get autographed. He was one of those pay me twenty bucks for a signature types, so I passed on a photo.

I’m campaigning for the phrase “Biting the Carl”, but to use the old one- certainly by the time it got to the telekinetic girl the series had jumped the shark. Well before that, but exactly when is debatable. As a completist I have seen most of them, but without more than just the killing, despite my yearning for the offbeat, I didn’t get too excited by the lack of originality.

I’m going purely on memory here, and I might be jumping the gun and should watch my copy. 1988’s April Fool’s Day I believe was more about finding the severed head shock value than actually showing the slaughter. I do remember I liked it first view and the several rewatches. Because it has that key element. Not a little bit of mystery. DEBORAH FOREMAN!!!! Shame she disappeared.

LikeLike

Somewhere within A New Beginning; I’ll be looking out for the precise moment this time around. 🙂

April Fool’s Day is…well, it’s a number of things that I don’t want to get into out of context, except to say that I’m looking forward to taking a better-informed look at it. And I agree about Deborah Foreman, although of course my personal impulse is to squeal AMY STEEL!!!!

LikeLike

I changed my mind. I had planned an April Fool’s joke trying to see if someone who hadn’t seen it would bite. Then after the ensuing confusion I was going to link a fake alternate ending URL. Which was going to be a Rick Roll.

Because it’s too hard to get people to fall for an April Fool’s prank anywhere near April 1st.

So to explain to those that aren’t familiar with the film (SPOILERS)

– the killings were faked. There’s no slaughter on screen because there’s no slaughter.

Another reason for giving up on the prank is uncertainty if anybody here would even understand or appreciate a Rick Roll.

But the Deborah part is true. She’s adorable. At least this motivated me to add my review to Lobster Man from Mars on IMDB.

LikeLike

Heh. I recently had a discussion of this (along with other genre films) with Tom Connors of Midnight’s Edge and part of the conversation dealt with the legal battle between Sean Cunnigham and Victor Miller over rights to the original film. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9TkU2To69Kg But the thing they’re fighting over, and which might actually win the suit for Miller, is the twist on Alfred Hitchcock’s ‘Psycho’, turning the concept of the dead parent who ultimately consumes the mind of the child on its ear by reversing it: in this case, the dead child subsumes the mind of the parent.

LikeLike

Interesting, thank you!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on Mike's Movie & Film Review.

LikeLike

And I should also add Friday the 13th holds a dubious distinction for me. I have seen it (in this order) via word of mouth from my older sister, on Betamax, on VHS, on old school Laser Disc, on broadcast TV, on basic cable, on premium cable, on Monstervision, digital streaming, on DVD, on BluRay, at a Drive-In theater, under a hardtop, expanded through the novelization, three separate ‘making of’ texts, and countless behind the scenes documentaries. No other film, even Star Wars, holds that distinction. Loved it then, and I still love it now.

LikeLike

Brilliant! 🙂

There’s actually a ten buck midnight screening of it on here tomorrow night, though I’m not really up to watching it twice in a week. (Although that said, I was thinking of forcing bits of it on my brother, to whom I’ve been banging on about my Final Girl theories…)

LikeLike

Another plot for Lyz’s future film career: Revenge of the Snakes. A cheap horror film production is shooting in a remote location, but the local snakes don’t want to be exploited any more…

LikeLike

“We’re mad as hell, and we aren’t going to take it any more!”

LikeLike

Through in Ray Milland and some frogs and insects….oh, that’s been done.

LikeLike

“We’re mad as hell, and we aren’t going to take it any more” is a good summation of the final act of a lot of those Hong Kong snake movies; unfortunately it’s usually prompted by an hour’s real snake-killing. 😦

Frogs, on the other hand, is the greatest movie ever made because the uprising is not prompted by onscreen violence, just endemic human dickery.

Time to copy over some snake movies, I think…

LikeLike

Throw….I can’t even blame that on autocorrect, just not paying attention. I have a lot of killer snake movies. I’m especially fond of Silent Predators for the insanity of the title, completely ignoring why rattlesnakes rattle in the first place. And it’s very Fredish all throw and throw. <——- (thus, the cosmic balance of bad grammar is maintained).

LikeLike

🙂

Aww, I love Silent Predators and its noisy, noisy snakes!

Yup, definitely feeling some snake films in our mutual futures…

LikeLike

For what it’s worth, in the massive documentary on the Ft13 franchise, the actress who played Marcie formally apologizes to any snakes who happen to be watching for what happened to the snake in that scene.

Probably won’t be enough to save her when the snakes come for their revenge, though…

LikeLike

Well, that’s nice to hear, anyway.

I haven’t tackled any of those docos yet, but I’ll probably get around to it when I finish this re-sweep of the franchise.

LikeLike

I think the reason the males get killed quickly while the female deaths are drawn out is that audience sympathies tend toward protecting females. When we watch women being pursued, the thought is to want to protect them, whereas we think men should be protecting themselves. Maybe that’s just my caveman mindset, though.

And yes, I’m sure there are people who simply enjoy long drawn-out suffering, but I don’t know what to say to those people.

LikeLike

Although the ultimate lesson of slasher movies is that you can’t depend on anyone but yourself.

I don’t think it’s as straightforward as that. For one thing the men are rarely given a chance to protect themselves, because they hardly ever see it coming. You could argue that the skimpy-clothing scenario is to increase the sense of female vulnerability, but (i) it’s hardly necessary when someone’s being menaced by a psychopath with a machete, and (ii) the way those scenes are shot undermine the suggestion that it’s just about increasing audience concern for the victim.

LikeLike

I once saw, in a comics-and-film-and-such shop, a set of photo cards titled “women in terror” (various stills from film rather than newly produced). I assume that some fraction of the horror film audience wants to see just that.

LikeLike

I suppose so, sigh. But you would like to think that the film-makers aren’t specifically catering to what we hope is a minority.

LikeLike

Like it or not, films that highlight violence against women are, on average, more likely to draw male audiences than films that highlight violence against men. I don’t presume to know why that should be, but it’s kind of an inescapable conclusion.

AFAIK female audiences don’t tend to unduly gravitate toward either.

Thus, films that highlight violence against men would not particularly draw in either male or female audiences, while films the highlight violence against women would draw in male audiences, and IIRC male audiences tend to be the most sought-after demographic. It’s all about the money, just like it always is.

Then again, another possible interpretation would be:

“Well, who gives a damn if MEN die, anyway?!”

Which was debatably kind of one of the central themes of the Vietnam War, so…

LikeLike

“Well, who gives a damn if MEN die, anyway?!” All the action films full of men dying by the dozens could be seen to support that. It could just be, though, that men are…I don’t know if “expected” is the right word, but definitely are more likely to go out and fight and die. However, considering how well such movies do, I don’t think we can say that no one is drawn to movies that hightlight violence against men. No one watches, say, an exploding bamboo movie because they anticipate a bunch of women being shot down or blown up. Further, while I certainly haven’t kept track, I have a feeling the numbers of men and women I’ve seen die in horror movies are probably about even. I think only a particular type of individual specifically watches a movie to see one gender or the other get killed; most people want to see people live or die based on the character, and if they die want a good show of it.

LikeLike

I can’t imagine why you would append “like it or not” to an observation like that. 😕

The overall point here, though, is similar to the one I was making: men get anonymously slaughtered, but the deaths of women get dwelt upon—whether because we are presumed to “care more”, or conversely because a section of the audience is presumed to enjoy it.

BUT – and this is the argument that Carol Clover was making in the first place – if it’s all about rigid gender rules and who should be protecting others and protecting themselves, and who “should” be dying, how do you account for the phenomenon of the Final Girl?

LikeLike

Hah, my husband and I actually watched this one and the first sequel only a few months ago after doing the “remember when you saw it the first time?” conversation (I sure do–my sister and I watched it by ourselves, at night, alone, on Showtime. We were so sophisticated and proud of how well we dealt with FINAL SCENE OH MY GOD WE WENT THROUGH THE CEILING.)

Rewatching the film as adults, knowing the ending and all, makes for noting some pretty hilarious bits–like, the galley has one regular, four burner stove and regular size fridge. For cooking for multiple campers and staff, three meals a day, for how many weeks at time??? Heck, Annie probably looked down from Heaven and went hey, I woulda walked out after seeing that setup anyway…

Plus, the filmmakers inadvertently threw in a pretty trenchant bit of social commentary, even though I’d bet dollars to doughnuts they didn’t realize it. It’s when Annie is riding with the truck driver and he’s outlining the history of accident and blood at the camp, then asks her who exactly is even going to be attending this deathtrap anyway?

Annie says, basically, that a bunch of “inner city” kids will be the camp’s re-opening set of paying guests. Then, as now, “inner city” is usually code for “minority,” and the clear hint is that the locals won’t have anything to do with actually sending their children to this place, but hey, if some outsiders want to spend their money…and they should probably count themselves lucky to find an affordable outdoor place to spend the summer, right?

LikeLike

Heh! Yeah, it still works surprisingly well. 🙂

We don’t do the summer camp thing AT ALL here, so the whole thing is rather mystifying to me.

You may well be right about the intended visitors. On the other hand I would suggest that we’re only seeing the staff facilities, and that there’s a bigger kitchen / dining-room set-up somewhere for the campers that we don’t see. (Perhaps because Annie doesn’t show up: it’s her work area, and the others don’t touch it.)

LikeLike

Is it just me — and I’m fully prepared to be told that it’s just me — or does Alice have a sort of androgynous sort of early-Kristy-McNichol tomboy quality?

On one hand, based on stereotypes of the era, that would qualify her as “mannish” and there’d be the underlying idea that women must “forfeit some of their femininity” in order to survive.

On the other hand, those very stereotypes would dictate that her tomboy-ish looks “prove” that she’s a lesbian, in which case, cool, early LGBT heroine.

Then again, I’m just putting too much thought into it. 😉

LikeLike

Given that the whole group is dressed for country life and manual labour, I don’t think we can read too much into her appearance. The only visual ‘separation’ is that unlike Marcie and Brenda, she doesn’t strip to a bikini to go swimming; but I would say that’s more a sign of her increased sense of responsibility, a la Laurie Strode vs Annie and Lynda.

As far as ‘signifiers’ go, I’ve always been much more intrigued by Brenda’s unlikely neck-to-toe nightie. 🙂

LikeLike

Looking at the photo of her in the canoe on the B-Masters Cabal page, I had this sudden MST3K callback:

“This is where the fish live.”

Honestly not sure why…

LikeLike

A totally interesting thought on the lead character’s femininity. I always thought she had a Dutch-boy haircut going on, and I think some of it is a bit of the 70’s going on, but there is something to her not being filmed in hot pants and screaming all busty-like. She also seems to be the most modernly mature of the girls, Brenda is old-fashioned and a little prudish, while Marcie is a pretty typical teenage girl. If we assume that nothing is done by accident and everything in art has its purpose, then I think you’re onto something!

And P.S. – what good is a movie if you can’t put a lot of thought into it, if you want to?!

LikeLike

Not sure if you’ve seen it but my all time favorite example of the Final Girl phenomenon is in the film Just Before Dawn. Great rarely talked about killer in the woods film.

LikeLike

I’ve mentioned that one to Lyzzy. It’s been a while, so I don’t remember how well she does overall as a Final Girl, but I do know she performs the most outrageous takedown of a killer I’ve ever seen from one. I’ve also floated Sledgehammer at her, as I found that particular Final Girl to be pretty memorable.

LikeLike

Yes, yes – they’re on The List. 🙂

Welcome, Cory! Thanks for chipping in.

LikeLike

Does it count as The Final Girl if it’s the only girl, but the other victims are part of the plot? Naked Fear.

LikeLike

Depends how it plays out. Times like these I trot out good ol’ Justice Potter Stewart and say, “:I know a Final Girl Sequence when I see one.” 🙂

LikeLike

So if that’s the criteria for policing the application of the Final Girl label it makes you a Malle cop.

Anyway. For Naked Fear I would say it counts. Not that it matters. And I may be influenced by Joe Mantegna’s brief scenes and my inflated opinion of the film. He is #4 on my bucket list of people I want to meet.

And Joe is a cop in the movie. Now sign of a mall, but that should count for something, right?

LikeLike

That’s Naked Fear (1999) , right? Because Naked Fear (2007) has a completely different plot.

Among other points of interest about the latter film

uh, SPOILERS, I suppose

, the protagonist (she can’t really be called a final girl because for most of the film, she’s the only victim) ends the film as a slasher/vigilante Ms. .45-style. THAT’S what I’d call a set-up for a sequel, but after eleven years, it seems safe to presume there won’t be one. 😐 IMHO Texas Chainsaw 3D (2013) offers an even better set-up for a sequel — too bad it couldn’t cross over with Wrong Turn 6: Last Resort (2014) — but I’m off-topic enough as it is. Sorry about that.

LikeLike

“Yes, yes – they’re on The List”

May we please see the list? 🙂

LikeLike

“I can’t imagine why you would append “like it or not” to an observation like that”

Just…habit, I guess. My sincere apologies. 😐

Perhaps the Final Girl is intended as a last-minute “justification”: “See, the monster gets killed by a woman so the movie isn’t really misogynistic after all!”

Of course, that implies that the filmmakers were self-aware enough to recognize the misogynistic themes to begin with, which seems a rather dubious prospect to me.

In his non-fiction “Danse Macabre,” Stephen King, when discussing (of all films) “Horror at Party Beach,” points out that the use of nuclear waste to create the monsters surely wasn’t intended as an attempt to call attention to the dangers of nuclear energy but was probably just the first thing the filmmakers thought of as an “origin” for the monsters…which King considers significant as an insight into the filmmakers’ zeitgeist (OSLT; please trust me, it makes sense when HE says it).

Maybe that’s the significance of the Final Girl trope, that the filmmakers never intended it to be significant at all.

They set up the situation of a woman being the last character standing because, as they perceive it, a woman-in-peril draws the audience in more than a man-in-peril.

Which is, as I theorized, probably exactly why all the OTHER female characters were so graphically butchered in the first place.

And because the slasher film is one of the most cookie-cutter genres there is, imitators of the early slasher films included Final Girls just because they were imitating those films without giving the trope any thought at all (much like the makers of “Horror at Party Beach” probably used nuclear waste as a plot point without giving it any thought at all). They considered the Final Girl just another basically meaningless detail to repeat, and that very repetition ultimately resulted in audiences considering her to be VERY significant.

OSLT..

Does any of that make any sense at all? I’m fully prepared to be told that it makes no sense at all. I’m just blue-skying here.

LikeLike

Sure, you can understand that having decided on a female killer, the makers of F13 realised that the balance of the climactic fight would be better served with a girl; and after that, simple copy-catting played its part; but I’m still trying to get at why, when they do tinker with the formula of the Final Girl, the results are always so unsatisfactory.

I’m intrigued by this contradiction of thousands of years of folklore which insist that, at the end, a man has to arrive to slay the monster and save the girl. It isn’t just that this doesn’t happen, it’s that it doesn’t work if it does happen.

Are we back to the original point of no-one cares if a man dies? Is it that having a man throws off the dynamic? – or that it just spoils the fun? And is it simply that? – that the more apparently unfair the fight, the greater the fun?

LikeLike

I think it’s a sophistication of the basic story – moving into two dimensions of badassery rather than just one.

In other words, if you have just one dimension (A is tougher than B, B is tougher than C) then in order to keep tension you need to have the principals killed off in ascending order of toughness. But clearly a Final Girl is not tougher than the jocks who went down the meatgrinder before it was her turn. So in order for her to have a chance of winning there has to be something different about her, something special – whether that’s simply that she has the least moral turpitude, or that she’s smart (or genre-savvy).

For an audience that, to a first approximation, likes to think of itself as not like the jocks, and a bit special, that may well have a visceral appeal.

There’s also the narrative transformation: from inoffensive person into monster-fighter. The less monster-fighty the Final Bod is beforehand, the more it’s “rising to the occasion” rather than “being tough in the first place”. This is an ordinary person, says the shape of the narrative, who doesn’t fight for fun but will be vicious if she’s pushed into it (which matches the broad Western mindscape in that conflicts among women aren’t meant to be seen by the men and therefore aren’t usually physical); it’s the opposite of the already-tough guy who goes up against challenges, your Rambo 3 and such like.

I would expect a male Final Bod that works to be the nerd or clown stereotype much more than the jock.

LikeLike

Way back when I reviewed Westworld, I pointed out how both that film and Deliverance kill off their “action men” and have their non-physical thinkers survive. Subsequently in the musclebound 80s, it seems that that choice was forbidden for men, but was considered permissible for women. 🙂

LikeLike

“. . . while the off-kilter performance of Betsy Palmer, cast perhaps as much against type as anyone ever was, is genuinely memorable.”

I actually went to see FRIDAY THE 13th when it was released, and your statement above, my old friend, marked my biggest take-away from it.

My best memories of Betsy Palmer was of her as a regular panelist on I’VE GOT A SECRET, and she was one of the most endearing ladies I’ve ever seen on a screen. Not Hollywood charming, but genuinely warm and considerate, a genuine version of “the girl next door”. (That was one of the things about old panel and quiz shows, like I’VE GOT A SECRET and TO TELL THE TRUTH and PASSWORD, in which celebrities co-existed with ordinary folks. There was no fooling the camera; it was obvious which celebrities were genuinely nice people and which were just tolerating having to associate with “the little people”.)

Yet, to anyone born after, say, 1965, who’s seen FRIDAY THE 13th, it’s impossible for them to believe just how sweet Betsy Palmer was. All they see her as is the crazy Mrs. Voorhees. That’s how remarkable an acting job she did, flying in the face of her actual personality, to re-brand her image.

The other real thing that lasts with me about FRIDAY THE 13th is the one everybody acknowledges. The final scene of Alice alone in the boat on the lake jolted me like no other scene in a film ever has. That’s the one that sent my popcorn flying. And, as I suspect holds true for every other viewer who experienced that scene, every slasher/horror film I’ve seen since, I watch the conclusion half expecting the same kind of shock.

In that way, along with the others you mentioned, Lyz, FRIDAY THE 13th left its mark on cinema watching.

It’s been way too long, my friend, and I’ve been spending the last couple of days catching up on your reviews.

LikeLike

Oh. My. Goodness.

Looks who’s here! 😮

It has been a while, hasn’t it?? 😀

Yes, I get the feeling that at least a portion of the contemporary backlash stemmed from a sense that the film had somehow “desecrated” Betsy Palmer. I’m somewhat in the revisionist category, in that now when I see her in something earlier there’s now always the feeling that the sweetness is covering for something else…

I genuinely admire her acting in the revelation scene—which is even more important now than it was at the time: the entire franchise is built on Palmer’s delivery of the half-line, “Jason was—”

As noted, it was that last scene shock that sold the film to Paramount. And again the film benefits from being first, because of course afterwards everyone was on guard and waiting for it.

Coincidentally I have just discovered something fairly rare that I will probably be reviewing in the New Year, which (I gather) features Betsy Palmer being much more “herself”.

Anyhoo—lovely to get a visit from you again, and I hope you’ll continue to drop in! 🙂

LikeLike

Count on it, Lyz!

I was half afraid that you wouldn’t recognise me. In filling in the blanks required to post my comment, I unthinkingly entered the unadorned, sans-honourific version of my name that I use for generic matters. Of course, I didn’t catch it until after I’d posted, and I couldn’t find a way to edit or change it. But I trusted your keen wits and good memory to remember an old friend.

A few days ago, I was watching a movie I’d recorded, an old favourite which I hadn’t seen in decades, and one which you had reviewed several years ago. As I watched, I recalled some of your comments about the film, ones I’d happened to agree with. (Both of us find the film not as bad as most of the popular wisdom insists.) That prompted me to return to your site here, and, boy howdy, how new your site looked! And I had a lot of catching up to do. I started reading your reviews, beginning with the films that I had also seen, since it’s the most fun to see what you observed about the same films and on what aspects we agree or disagree. Your comments on FRIDAY THE 13th were the first to which I had anything to add.

Your commentary is still as incisive as ever, and wry. (Nothing you’ve ever written in a review has ever kept me chuckling as much as your refrain about the “one heroic button” in your review of I KNOW WHAT YOU DID LAST SUMMER.)

Never fear, I’ll be around.

LikeLike

Never any danger of that. 🙂

Thank you for your kind comments. It’s great to have you hunt me up again. As you will observe I still have a LOT of transferring / revising to do but I’m trying to keep it ticking along.

LikeLike

I propose an alternate hypothesis about the “boys die in shock moments; girls get long stalk sequences” observation.

Despite inheriting substantial DNA from the giallo, I would contend that slasher films are essentially horror films; their central appeal is allowing the audience to vicariously experience fear. If not for gendered expectations, it’s my belief that a canny filmmaker would be delighted to put as many of his Expendable Meat characters through lengthy stalk sequences as possible, because such sequences deliver stronger, more sustained doses of what the audience came for.

However, gendered expectations DO come into play. The fact that they’re often quite ridiculous expectations doesn’t stop them from being present. If a female character becomes aware of the slasher’s lethal threat, she can respond with either fight or flight, without losing audience respect. (Albeit we don’t expect either response to ultimately succeed, unless it’s the end of the movie, and a female character other than the Final Girl responding with ‘fight’ is sadly rare.)

But what about male characters? A male character can look cowardly if they run, despite that being a VERY sensible thing to do. Even more, a male character who physically fights a slasher only to be defeated (which, again, is practically unavoidable except at movie’s end) is often diminished in audience eyes by the loss. Look at how audiences mocked Julius from Part VIII because, being only an athletic human, he lost badly to an immortal zombie. Almost the only non-Final Girl who ever attempted to stand up to Jason, and he became a punch line.

My hypothesis, therefore, is that male characters tend to be killed suddenly, without time to react, BECAUSE so few reactions they could have, whether fight or flight, could prompt the correct response from the audience.

As supporting evidence, I point to the “Nightmare on Elm Street” series. Freddy represents a quite different kind of threat, and there’s no gendered expectations that males ‘should’ be able to fight off a dream invasion and if they don’t, they’re lesser males. And in those movies, there are some quite lengthy sequences of males being stalked and killed by Freddy – notably John Doe, whose flight from Freddy takes up a substantial amount of the beginning of “Freddy’s Dead”.

Anyways, that’s my hypothesis, for what it’s worth. I’d be interested in hearing whether others think it holds up.

LikeLike