“If that’s so…then we human beings are nothing but puppets of some force or other, which we cannot possibly escape…”

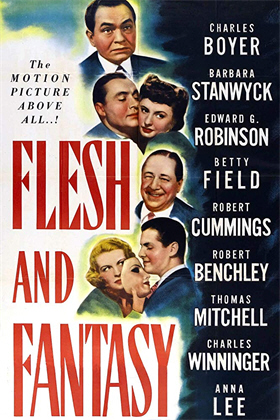

Director: Julien Duvivier

Starring: Robert Benchley, Betty Field, Robert Cummings, Edgar G. Robinson, Thomas Mitchell, Charles Boyer, Barbara Stanwyck, Edgar Barrier, May Whitty, Anna Lee, C. Aubrey Smith, Charles Winninger, Clarence Muse, David Hoffman

Screenplay: Ellis St. Joseph, Ernest Pascal and Samuel Hoffenstein, based upon the works of Oscar Wilde and László Vadnay

Synopsis: Mr Doakes (Robert Benchley) admits to fellow clubman, Mr Davis (David Hoffman), that he has been disturbed by a dream; or rather, by the dream that followed his encounter with a fortune-teller—the one telling him he would do a certain thing, the other that he would not. Therefore, Doakes laughs, he is destined to prove accurate either fortune-telling or dreams… This exchange leads to a conversation about the reality, or otherwise, of predictions of the future, and how far human lives are dictated by destiny. Davis then chooses a book from the shelves of the club library, and together he and Doakes consider three tales of the supernatural… In New Orleans, as others celebrate Mardi Gras, a young dressmaker named Henrietta (Betty Fields) broods over lonely life, one full of bitterness and without love: something she blames upon her plain face. Finally in despair she contemplates suicide, but is prevented by the intervention of a mask-maker (Edgar Barrier), who offers her the chance to see the world from a different perspective… In London, the centrepiece of a gathering hosted by Lady Pamela Hardwick (Dame May Whitty) is the palmist Septimus Podgers (Thomas Mitchell), whose assessments of the guests are alarmingly accurate. American lawyer Marshall Tyler (Edward G. Robinson) reacts to Podgers’ reading of his hand with scorn; though he is forced to change his mind when Rowena (Anna Lee), who he has long loved in vain, finally confesses her love for him—just as Podgers predicted. Aware that, during the reading, Podgers saw something in his hand which he did not reveal, Tyler pursues the palmist until he forces him to talk—and learns that he is destined to commit murder… After witnessing an accident on a London street, the aerialist Paul Gaspar (Charles Boyer) returns to his circus, to rest before his performance. Known as “The Drunken Gentleman Of The Tight-Rope”, Gaspar’s dangerous high-wire act climaxes with his netless leap from one rope to another below it. Falling into a doze, Gaspar experiences a terrifying dream: his own death-plunge, watched by a beautiful woman wearing distinctive, lyre-shaped earrings, who screams in horror…

Comments: When the Laemmles were forced out of Universal Studios in 1936, control passed to the Standard Capital Corporation, a New York-based finance company from which the Laemmles had borrowed in order to produce the James Whale-directed Showboat. The head of Standard, John Cheever Cowdin, became president and chairman of the board of directors of Universal; and, being a money-man and not a film-maker, his first act was to rein in the studio’s expenditure. He disposed of Universal’s chain of cinemas; he slashed costs and salaries, resulting in the departure of most of the studio’s contracted stars; and he announced a production schedule dominated by franchises other and inexpensive B-movies, with only a very occasional foray into the realm of the “prestige picture”.

One such prestige picture was 1943’s Flesh And Fantasy—although predictably, the newly cautious Universal did not take this step without good reason to believe that their investment would turn a profit. The specific motivation was the previous year’s Tales Of Manhattan, a 20th Century Fox production based upon a novel by the Mexican author, Francisco Rojas González—though no less than seventeen people, credited and uncredited, would eventually work on its screenplay, among them Ben Hecht, Donald Ogden Stewart, Billy Wilder and Buster Keaton. Tales Of Manhattan is an anthology film, comprising five stories linked by the device of a cursed evening-jacket, which passes from hand to hand and influences the life of each of its owners for better or worse. Offering a literal all-star cast, Tales Of Manhattan was both a critical and popular success, and turned a tidy profit in spite of its production costs.

(Tales Of Manhattan originally included a sixth story starring W. C. Fields, but it was cut before the film was released. In the 1990s, a copy of the sequence was discovered in the Fox vaults, and today most prints of the film include this sequence.)

Despite committing to the production of Flesh And Fantasy, Universal moved cautiously, duplicating Tales Of Manhattan in a number of ways, including hiring one of that film’s many screenwriters, Samuel Hofferstein, and basing one of its segments upon a story by another, László Vadnay. The company also signed two of the earlier film’s headlining stars, Edward G. Robinson and Charles Boyer. This latter move was perhaps the most significant: Boyer’s involvement was secured by an offer to co-produce the film, his first foray into production; and this in turn helped to secure the services of French director, Julien Duvivier.

Considered one of “the Big Five” of classic French cinema, along with Jean Renoir, Marcel Carne, Rene Clair and Jacques Feyder, Duvivier was much celebrated for his so-called “poetic realism”, his ability to find lyricism and wonder in tales of ordinary life. However, during the 1930s, he also directed two films dealing with the outright supernatural, both of them remakes of famous silent horror films: Le Golem, a version of the famous Jewish legend previously filmed in 1920 by Paul Wegener; and La Charrette Fantôme, an adaptation of Selma Lagerlöf’s novel, Körkarlen, filmed under that title in 1921 by Victor Sjöström, but better known as The Phantom Carriage.

In 1937, Julien Duvivier’s Pépé le Moko caught Hollywood’s attention, and he was invited to work in America—though not on the inevitable remake of his film (which, under the title Algiers, would be directed by John Cromwell and star, somewhat ironically, Charles Boyer). Rather, he was given a completely dissimilar production, The Great Waltz: MGM’s biopic about Johann Strauss. It was a troubled production marked by studio interference, giving the director a difficult introduction to Hollywood. However, with the situation in Europe deteriorating, Duvivier began to alternate his work between America and France. He relocated altogether in 1941, directing Lydia, a remake of his own Un Carnet de Bal, for Alexander Korda’s London Films, before making Tales Of Manhattan—leading in turn to his hiring by Universal.

Horror films fell out of favour in the late 1930s, with the studios if not with the public, chiefly because of the anti-horror crackdown in England and the drying up of that previously lucrative market; while, with the coming of war, there was a general feeling that the real-world horrors were quite sufficient. Consequently, what horror movies were produced in the 1940s tended to be non-threatening in nature: a harmless thrill, rather than anything intended to disturb or frighten. For Universal, this meant turning their iconic 30s monsters into franchise characters, and then bringing them together in their enjoyable but distinctly unhorrific “monster-mash” films.

And for all that it is a relatively high-budget, star-heavy production, Flesh And Fantasy sits comfortably within this paradigm. Though certainly not without its virtues, this is a tentative film, self-conscious about its horror elements, and determined to undermine anything which might actually unnerve the viewer. Though watchable for its cast and, even more so, its cinematography and art direction, it is finally an intentionally compromised work.

In fact , “compromise” is a work we can apply to Flesh And Fantasy in more ways than one. As with all anthology films, it was necessary for the film-makers to decide how many short stories the production would contain, and in which order they would appear so as to have the correct impact. Prior to its release, therefore, the film underwent considerable testing to gauge audience response; and viewers were essentially unanimous in declaring that of the four stories presented, the strongest was that starring Gloria Jean and Alan Curtis, playing a blind girl and an escaped killer, respectively.

To which Universal responded by removing that segment from the film altogether.

It is unclear why this puzzling step was taken, though it has been suggested that some of the film’s bigger names were affronted at being upstaged by their lower-billed cast-members. Alternatively, Universal may have felt that the material was too good to be “wasted” as a mere short. In any event, the segment was subsequently turned into a feature-film, Destiny…with, perhaps, the inevitable result: in being padded out, it lost much of its impact; while the studio also felt compelled to tack on a happy ending.

(Another piece of compromise was associated with this segment: John Garfield was originally loaned out by Warners for the part eventually taken by Alan Curtis. For reasons unknown, he was so strongly opposed to it that he refused the role, and was suspended by the studio for his pains.)

Having removed one of its four stories, the makers of Flesh And Fantasy were obliged to find a way of restoring its running-time; and finally they settled upon a series of linking scenes, in which two minor characters discuss fortune-telling and predictions of the future, and whether fate is set in stone or we shape our own destinies; whether, in short, the fault is in the stars or in ourselves. And while these scenes could have had an ominous tone, and added a sense of foreboding, the film’s hand is tipped in the casting of Robert Benchley, at the time best known for his humorous short films and supporting roles in various romantic comedies. The message sent by his appearance in the framing device is sadly evident.

Benchley plays a clubman called Doakes, who has been disturbed by two consecutive events: a fortune-teller at a party told him he was to do a particular thing; while afterwards, he dreamed that he would not do that thing…so one of them, the fortune-teller or the dream, must be right.

Davis, to whom Doakes is speaking, tells him of a book to be found upon the club’s shelves, which he has just been reading: a book of strange stories dealing with precisely such things. He persuades the reluctant Doakes to listen while he reads out loud the first of them…

In denouncing the first segment of Flesh And Fantasy as its worst, I admit frankly that I’m expressing an opinion both personal and prejudicial…and I don’t back away from it one little bit. The New Orleans-set story is a compendium of all the pernicious, psyche-damaging rubbish thrust upon girls from the time they’re old enough to understand what the word “pretty” means: that your worth as a human being depends upon your appearance; that pretty people are good, and ugly people are bad; and that no-one will ever love you if you’re not beautiful—and nor should they.

Our object lesson is Henrietta, a young milliner. She is plain, and lonely and bitter; or rather (we are told) she is plain because she is lonely and bitter; evidently the bitterness came first, somehow. In fact, we’re told that she was, “Born with this load of hate.”

Be this as it may, it might seem that Henrietta has good reason for her current bitterness: she earns her living catering to pretty girls who make their contempt for her evident while making use of her talents; and the man she loves remains oblivious to her existence, though she tries repeatedly to edge herself into his world. She is plain, therefore (literally, evidently), he cannot see her.

On Mardi Gras night, Henrietta has a confrontation with a customer, who has ordered a new dress from her but cannot pay for it. The young woman begs to be allowed to take the dress first and pay for it later, but Henrietta is in no mood to do favours. Her attitude sees the customer’s pleading turn into abuse:

Customer: “It’s Mardi Gras tonight, and my sweetheart will be waiting for me. We’ve been counting on it for so long… Henrietta, please! – listen with your heart! We love each other so much!… You don’t want anybody else to have any loving, just because you haven’t got any! How could you? You’re ugly! No man would ever look at you! – and if he did, he’d sooner see a dead cottonmouth! I hate the sight of you! – and everybody does!”

And of course, it’s Henrietta who is deemed to be in the wrong here, because she doesn’t “listen with her heart”, that is, sympathise with the young lovers to the point of handing over her work for free: two days’ solid work, which left her eyes, “Feeling like they were riddled with needles.” Her rejection of the girl’s romantic pleading – “That don’t pay my rent!” – is not merely dismissed as of no importance, but taken as diagnostic: a heart so hard can only result in an ugly face.

Having chased away her dissatisfied customer, Henrietta goes outside to see why people are milling around at the edge of the water, and becomes one of the crowd gazing in superstitious horror at the dead body that has been pulled from of the river.

(This is reused footage from the cut sequence, given a very different meaning here.)

Then Michael, the struggling young law student to whom she has lost her heart, pushes his way through the crowd, almost to her side. She speaks to him, hoping to win some notice, but he barely glances at her before moving away…

This second rejection is the last straw for Henrietta, and in her desperation she heads for the edge of a nearby cliff. She stands there, gazing down, gathering herself—

—and a hand closes on her arm. It’s a man, a stranger, who scolds her gently for her intention. Henrietta pours out her woes and, after a speech in which he insists that her life is not shaped by her face, the man offers her a chance to be beautiful, if only for a few hours…

He turns out to be a mask-maker, and has her select a disguise to wear for the remainder of Mardi Gras. While Henrietta searches for a mask with, “That soft, sweet look men seem to like,” the mask-maker lectures her on the true meaning of love: how she must be prepared to give everything even with no hope of a return; and that when she has reached this pinnacle of unselfishness, she will hear the words: “You are beautiful; and your face is as beautiful as you are.”

Not, you notice, “It doesn’t matter that your face isn’t beautiful.” Heavens, no.

Henrietta finally chooses her mask, and the man sends her on her way, telling her that the mask must be back by midnight; to use the back-door to the shop if the front is locked; and, to make the best use of the evening, to go to a certain Café Mazarin…

Dressed in a costume of her own making, and with her face hidden behind her mask, Henrietta does as instructed. With her real face hidden, she goes out into the night with an air of confidence; and, though her new beauty is only a mask, men immediately begin to force their attentions on her. (Poor girl! – to think she never knew before the joys of being groped by a stranger!) One of her harassers is so persistent, she must be rescued—and looks up to find that her saviour is Michael. He invites her to take a glass of wine with him and, though he hesitates at first – “A pretty girl like you couldn’t possibly understand” – ends up telling her his woes: that he is tired of being an onlooker, “Only waiting for life, not living”; and that he is on the verge of throwing in his studies and giving up; that he intends to take a job on a ship and leave everything behind—almost immediately…

Henrietta devotes herself to changing his mind; to giving him faith in himself by expressing her faith in him. In a sense this backfires, as he ends up promising to believe, for and in, her. Henrietta protests, telling him that he doesn’t know her, that he only sees a mask; he doesn’t know what she really looks like:

Michael: “I know that your face is beautiful…because you are beautiful. It couldn’t be otherwise!”

And he removes her mask…

And guess what?

There’s an overtly supernatural twist to this tale, but that hardly excuses this outcome. Basically what we have here is a dishonest version of the plot later rendered at feature-length in The Enchanted Cottage: dishonest because that film has the grace to make it clear that the “new beauty” of its central couple is wholly in the eye of the beholder.

This isn’t good enough for Flesh And Fantasy, which finally suggests that Henrietta was “beautiful all along”, but could not see that she was, because of her bitterness; and that it is only when she puts aside her own troubles to help Michael with his (such as they are) that her inner beauty can show itself. Conspicuous by its absence, however, is any accompanying suggestion that inner beauty is enough. On the contrary, in the way it treats the first version of Henrietta – rendered via the time-honoured (and still extant) practice of taking an attractive actress, in this case Betty Field, and “turning her ugly” via unflattering makeup, lighting and camera-angles; and, of course, glasses – the film is apparently expecting a cry of, “KILL IT WITH FIRE!!” from the horrified viewer.

Back at the club, we find Doakes protesting that this story hasn’t anything to do with his own situation; while Davis counters that the moral of the story is that “fate” rests with the individual, and that no outside force – be it a dream or a fortune-teller – has the power to make anyone do anything that it is not within their nature to do. He backs up this argument with the next story in the book…

There is little question that, of its three stories, Flesh And Fantasy positions its strongest one in the middle. That said, it is not, perhaps, what it could and should have been, since the Hayes Office saw fit to tamper with the story’s resolution: an intervention which, ironically, had the effect of increasing the paranormal overtones of the tale, since it removed the final twist that is present in its source.

That source was Oscar Wilde’s 1891 short story, Lord Arthur Savile’s Crime, re-set in contemporary times and re-cast with American lawyer in London, Marshall Tyler, played by Edward G. Robinson.

(The dominance of this story is perhaps best conveyed by the fact that, while the initial advertising for Flesh And Fantasy exploited the all-star cast, when the film was re-released some seven years later most of the artwork focused upon Robinson to the near-exclusion of his co-stars.)

Though Tyler is a welcome member of the society crowd that gathers around his client, Lady Pamela Hardwick, he remains something of an outsider—not least because of his cynicism about the endless fads in which Lady Pamela dabbles. However, Tyler continues to visit because he knows that he will meet at Lady Pamela’s house her goddaughter, Rowena, whom he has loved quietly and unavailingly for many years.

Lady Pamela’s latest fad is palmistry, as practised by her guest of honour, professional cheiromantist Septimus Podgers. Podgers causes a sensation by telling a Lady Carrington that she will soon hear from her husband—who has been missing, presumed dead, for two years, after a disastrous Antarctic expedition. Though Podgers’ readings of several other guests seem accurate, Tyler continues to hold aloof. He admits that he disapproves of the practice, but his real objection is he cannot accept that people are at the mercy of outside forces, unable to shape their own destinies. He nevertheless allows Podgers to look at his hand—and is more convinced than ever that the palmist is a fraud, when Podgers tells him that the lady he loves also loves him.

The tactless Lady Pamela immediately begins calling out for Rowena—who, several rooms away, is in the very process of ending a painful love affair, and suffering a complete revulsion of feeling…

Meanwhile, influenced by the suggestion that Rowena might indeed care for him, Tyler cannot resist the temptation of giving Podgers another look into his hand. For a moment an expression of startled horror crosses the palmist’s face; but quickly he protests that he has seen nothing of any significance; and he hurriedly wraps up the reading with a stock prediction about a journey.

Tyler is disconcerted, but he forgets all about Podgers when Rowena asks him shyly whether he will marry her? Unable to believe that he is to obtain his heart’s desire after so many years of waiting and hoping, Tyler hesitates…and at that moment, a newsflash on the radio announces that Sir Roger Carrington and his party have been found and rescued. Across the airwaves, Sir Roger speaks to his wife…

As the other guests cluster around the swooning Lady Carrington, Tyler catches Podgers just as he is about to leave the house, and insists upon knowing what else he saw in his hand. Podgers refuses to answer on the spot, but invites Tyler to visit him the following evening.

However, when he does so, Podgers initially protests that there is no point in him saying anything more, as Tyler has made his disbelief in his powers quite clear. He is finally swayed—not, we feel, so much by either Tyler’s peremptory demands nor his rather crass offer of a large payment, as by a desire to punish him for his attitude. He gives Tyler a character-reading that offends and infuriates him, speaking of his “magnificent ego”, and his determination, “To be right, even if he’s wrong”; adding that Tyler has no real convictions at all: “You would make an excellent criminal lawyer.”

When Tyler snaps that he is not interested in crime, Podgers laughs quietly…

Admitting that Podgers was right about him and Rowena, Tyler insists on knowing if the palmist can see anything in the future which might mar their happiness. Podgers suggest that he might be better off not knowing but, in the face of Tyler’s violent anger, he finally tells him coolly that what he sees in his future is murder…

Podgers: “You’re going to kill someone, Mr Tyler.”

The screenplay’s working-out of this situation is both enjoyably sardonic and genuinely unnerving, playing with questions of destiny and self-fulfilling prophecy as Tyler’s initial sceptism becomes first denial – “Man’s a fool! Cats all over the place!” – then reluctant acceptance, then wholehearted belief. It also allows for a tour de force dual-performance from Edward G. Robinson, as Tyler – in lieu of a little devil sitting on his shoulder and whispering into his ear – begins to have conversations with his own worst nature in the form of his reflection, which argues that if his fate is unavoidable, his most practical course of action is to embrace it; indeed, to rush to meet it. If he is destined to murder someone, why then, he should do so quickly and get it over with. Then he and Rowena can be married and live happily ever after…

But a victim? Having brought himself to concede that if he could push a button and kill someone thousands of miles away, to put an end to his mental torment – provided that the person was “old”, and “worthless” – it is a short step to recognising that there are old and worthless people much closer to hand; and that of all of them, the most worthless is Lady Pamela Hardwick. Poison seems the best method; only he doesn’t know anything about poison. Still, as his reflection points out, it’s never too late to learn…

Having planted a poisoned chocolate upon Lady Pamela in the guise of a new treatment for her liver disorder, and urged her to use it when she next has an attack – not until then – Tyler absents himself from London and hides away at a remote inn—even though this means putting off his wedding. A confused Rowena finally tracks him down there; but even as she is reproaching him with their long separation, his “few days” having turned into three weeks, Tyler receives a phone message that Lady Pamela Hardwick is dead…

At first elated, Tyler hurriedly conceals his emotion from the distressed Rowena, who reminds him that Lady Pamela was her godmother. The two are among those who gather for the reading of the will; and Tyler can only stare in bewildered disbelief when Rowena notices a charming comfit-box on the table, which holds a single foil-wrapped chocolate…

At first profoundly relieved to discover that he is not a in fact murderer, Tyler soon realises that the curse is still hanging over him, and that, having promised Rowena a quick wedding, he must choose another victim—immediately.

The main beneficiary of Lady Pamela’s will – much to the disappointment of her relatives – is the saintly Dean of Norwalk, who is left the bulk of the estate in order to do “good works”. The Dean’s response is to praise Lady Pamela’s charitable nature, and to speak reverently of the “happy release” of her death, her “freedom from tribulation”, and her attainment of the peace and serenity of the afterlife, for which everyone surely yearns: “Thou great liberator! – where is thy sting?”

He’s ASKING for it! thinks the incredulous but grateful Tyler, as his reflection smirks at him from a glass-topped table.

But with time short, Tyler realises that, this time, he’s going to have to get his hands dirty. He calls upon the Dean – who helpfully tells him that he is “quite alone” – and describes his own dilemma, in the guise of asking what advice he should give a client in such a situation. The Dean, taking in Tyler’s agitation, is obviously sceptical about the existence of this “client”, but answers gravely—dismissing the idea that anyone can know what the future holds, and arguing further that if God wanted man to know, He certainly wouldn’t rely on such vessels as Septimus Podgers.

Hoping that his words have sunk in, the Dean then goes to his wine cellar to get a bottle of port—and looks around from his task to find Tyler standing behind him with a mallet in his hand…

The Dean takes this calmly, telling Tyler to put the weapon down, “Lest you hurt yourself”; and after a stricken moment, Tyler does—then rushing out wildly into the foggy night. Striding on, and on, he wrestles with himself, unable either to relinquish his belief in his fate or to bring himself to take the action he believes will free him. His unthinking footsteps finally lead him, exhausted and distressed, to London Bridge, where he begins to contemplate a third option: suicide.

But as he hesitates, he hears someone approaching—and who should it be but Septimus Podgers…?

The third story in Flesh And Fantasy, which features Charles Boyer and Barbara Stanwyck as star-crossed – or dream-crossed – lovers, leads directly out of the second, with a violent incident on a London street witnessed by Paul Gaspar, a French aerialist, and his servant, Jeff. The latter speaks in puzzlement of what they have just seen and heard: “What did he mean—about something being in his hand?”

Gaspar dismisses the incident, wanting to rest a little before his performance. Known as “The Drunken Gentleman Of The Tight-Rope”, his specialty is a dangerous high-wire act full of deliberate swaying and staggering, which climaxes with a leap from one wire to another some twenty feet below—all done without a net.

(Charles Boyer was doubled in his high-wire scenes by the Australian acrobat and aerialist, Con Colleano.)

Gaspar settles down in his dressing-room and dozes off…and has a dream of terrifying vividness, in which he plunges to his death as a woman in the audience screams: a beautiful woman wearing distinctive earrings in the shape of a lyre.

Gaspar is so unnerved by the dream that it impacts his act: he is unable to go through with the final, death-defying leap; and as he climbs down, the disappointed crowd boos and hoots. Whether they were hoping for his success or his failure is left to our imaginations…

King Lamarr, the owner of the circus, is puzzled but sympathetic. He knows, too, that an aerialist who has lost his nerve is a danger to himself and a liability to the show. As it happens, this was the circus’s last London performance before the company’s departure for America. Lamarr urges Gaspar to use their journey to shake off the effects of the dream; or, failing that, to decide what he wants to do in the future; reassuring him that if he wants to go back to working with a net, he is at liberty to do so.

But once on shipboard, matters take a turn in the other direction when, amongst his fellow-passengers, Gaspar sees a woman who he is certain is the one from his dream.

The woman, Joan Stanley, is at first inclined to take Gaspar’s pursuit of her in a cynical spirit, seeing in his story that they met in a dream merely an elaborate pick-up line—until he mentions the earrings: she has such a pair in her possession, but has never worn them.

As the two get to know one another, they compare travel-stories, and realise that they have been just missing each other, all around the world, for several years…

But Joan continues to resist Gaspar’s simple acceptance that they were destined to be together. Even as they fall in love, she refuses to answer questions about herself or her past; and as they approach New York, she tells Gaspar firmly that theirs is simply a shipboard romance: once they dock, she will not see him again.

Gaspar’s confusion is only heightened when, as the walk around the deck, a man greets Joan as, “Miss Templeton.” She tells him coolly that he is mistaken, but the impression remains.

The upshot of Gaspar’s disturbed state of mind is another dream. This time it is Joan he dreams of: Joan in distress, Joan being pursued, Joan being hailed on all fronts as “Miss Templeton”; when he does it, she laughs at him. But no-one is laughing as a handcuff closes about Joan’s wrist…

And sure enough, the next morning, the details of Gaspar’s dream begin to come true—all except the last: Joan leaves the shipping terminal without incident. So relieved is Gaspar to have this dream proven wrong, not even Joan’s attempt to go on giving him the cold-shoulder can quench his delight; and when King Lamarr follows up his own suggestion that perhaps he should revert to his earlier, less dangerous aerial act, he waves the idea away, insisting upon his “Drunken Gentleman” routine. Furthermore, he insists that Joan be there to see it, waving away too her fear that she may be a jinx.

And Gaspar’s new confidence carries him through his act, wire-leap and all. Afterwards, overwhelmed with relief, Joan threads her way out of the audience and asks directions to his trailer. She is on her way when two men approach her: one addresses her as “Miss Templeton”; the other produces a pair of handcuffs…

Back at the club, Doakes and Davis debate this story, and the significance of Gaspar’s dreams, one of which came true if the other did not. What will happen the next time Gaspar does his act?

It is Doakes who puts his foot down, insisting that Gaspar cannot – that no man can – allow his life to be controlled by such dubious outside forces; chuckling ruefully as he realises that he now sounds just like Davis—

—Davis, who hurriedly stops him drinking out a glass held in his left hand, insisting that it’s bad luck.

Laughing outright, Doakes then heads for the club’s exit—making sure to sidle around, not walk under, the ladder in the doorway…

Viewed in its entirety, Flesh And Fantasy has a great deal of style but very little substance. It never really comes to terms with its own premise, being content instead merely to use it as a hook, an excuse for its stories. There’s a hollowness about it, a timidity that was too often the hallmark of the genre film at this time, at least at the “higher” levels of film-making: B-movies, ironically, were often more daring. The centrepiece story alone has both intelligence and wit; not surprisingly, given its source material. The other two, written specifically for this project, are terribly flimsy, making a lot out of not much. The third, in particular, carries with it a distinct suggestion that we shouldn’t be worrying about things like “depth”, when we can be watching Charles Boyer and Barbara Stanwyck fall in love.

Well—perhaps it has a point.

At any rate, the makers of Flesh And Fantasy weren’t kidding when they boasted about their “all-star cast”, and nor were they only referring to the headliners. Remarkable as is the film’s main ensemble, quite as much so is the supporting cast, an astonishing gathering of those familiar faces who enriched so many films in this era. Quick eyes will spot Bess Flowers, Lane Chandler, Eddie Acuff, Joseph Crehan, Mary Forbes, Doris Lloyd, Charles Halton, Ian Wolfe, Heather Thatcher, Bruce Lester and Hank Worden – among others! – while Gaspar’s manservant is played by Clarence Muse (whose character is, inevitably it seems, called “Jeff”), and a young Peter Lawford gets one line in the Mardi Gras sequence.

Furthermore, when I said the film had style, I was putting it mildly. Whatever the story faults of Flesh And Fantasy, it is spectacular to look at: cleverly designed by Robert Boyle, Richard Riedel and John B. Goodman, and beautifully photographed by Stanley Cortez and Paul Ivano in glorious black-and-white.

In this respect, even the first story redeems itself, at least a little. The Mardi Gras itself is rather too set-bound and artificial, but the finding of the body by torch-light, as people costumed and grotesquely masked look on, is powerful and unsettling. However, we recall that this footage was actually shot for the missing fourth segment. Leading with it also raises expectations that the film fails to meet. The third story, though content for the most part simply to put its equally stunning stars front-and-centre, also includes some effective, occasionally surreal montage-work, as Gaspar suffers his prophetic dreams. But again, it is the second story that steals the show, offering some interesting lighting effects as Tyler wrestles unavailingly with what he believes to be his fate, but dominated by the wickedly funny scenes of the lawyer arguing with – or rather, being persuaded by – himself, as the film-makers find an astonishing array of surfaces via which to catch the reflection (real or superimposed) of Edward G. Robinson.

Despite its shortcomings, Flesh And Fantasy was one of Universal’s top-grossing movies in 1943; and while we can probably chalk this up to its cast, it might also be an indication of how starved the public was for anything that might be regarded as “horror”. But if it was possible on a first viewing to enjoy the rather superficial pleasures of Flesh and Fantasy and to overlook its faults, a glaring spotlight was thrown upon those faults only two years later, when Britain’s Ealing Studios took a daring plunge into genuine horror with their production of Dead Of Night—and in the process gave the world an object lesson in what the anthology film could, and ought to be.

♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦

This review is part of te B-Masters’ examination of anthology films.

Those movie posters don’t really explain what happens in the movie. They just throw in a bunch of superlatives.

I always liked the Oscar Wilde story. The protagonist’s final resolution of his dilemma just seems so neat and wrapped up. Although I don’t think Robinson would have been my first choice to play an English aristocrat, I’m sure he did a great job. But spill! what was the final resolution? I can imagine the Hays code having a stroke over the way the story finishes.

LikeLike

Yeah, the fact that the posters avoid saying anything about the nature of the film is a dead giveaway.

Alas, the ending of a short story from 1891 was FAR TOO SHOCKING for audiences in 1943, so beyond a certain point the two versions diverge…

LikeLike

In the 1946 Warner Bros. cartoon “Hush My Mouse,” set at the cat-centric “Tuffy’s Tavern” (a takeoff of the TV program “Duffy’s Tavern”), Art the manager (who is prone to malapropisms) greets an Edward G. Robinson parody with, “Well, as me eyes deceive me! Eddie G. Robincat in the flesh and fantasy!”

So now I FINALLY “get” that joke. Thanks. 🙂

LikeLike

Welcome! 🙂

I suppose we have to consider it a measure of the film’s contemporary popularity that Warners would refer like that to a Universal film, and several years after its release.

LikeLike

Wilde’s cynicism certainly was a strong dose for 1940s American audiences! I love that short story; and nowadays, with our political firestorms, the cynical “talk yourself into what you want to do anyway” bits are pungent, indeed.

LikeLike

Now this is pretty much unrelated, but does relate to movie posters and not being able to gauge what the movie is about. And it’s about people with way too much free time on their hands inferring all kinds of crazy things.

In Avengers Infinity War, Dr. Strange mentions a very specific large number. To be exact, that number is 14,000,605. That’s the number of possible future outcomes he saw in the future on how to defeat Thanos, of which the heroes lose every single time except one.

You could just assume it’s a randomly picked large number to show how the odds are stacked against the good guys. Yet, somebody put up a theory on what this means for the final Avengers movie next year. The Infinity War poster has 24 heroes on it, and it just so happens that log(2) 14,000,605 is equal to 23.73985, rounded up to 24 even. The number of heroes on the Infinity War poster!

Which has more holes in it than the plot of most bad movies.

1). Why not the number other than 14,000,605 that yields exactly 24?

2). Why not the number of heroes at the end of the NEXT movie? They’ve promised us that some characters will be killed off?

3). And so what? Why does this have anything to do with anything?

And more. These things were all pointed out, yet still there are people that think this idea is cool enough to be noteworthy.

In this case I feel obligated to link the video to prove I’m not making this up.

LikeLike

No problem with the post per se, but this is pretty much what I set up “General Chatter” for… 🙂

LikeLike

Project Gutenberg has the story: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/773/773-h/773-h.htm . The ending’s what I would expect of the setup, and of Wilde; I suppose I’ll have to find the movie to see what changes the Code required.

LikeLike

Thanks for that! I imagine you can guess what the censors objected to…

LikeLike

Or maybe “Hush My Mouse”‘s writer(s) just couldn’t think of another Edward G. Robinson movie. 😉

More from Art:

(to an underling whom he sent to get “mouse knuckles” that Edward G. Robincat, uh, strenuously insisted be served to him but whom Sniffles the Mouse avoided being caught by) “Here I am with me life in piccady and you have the VERB to come back empty-handed!”

(to a fighting Edward G. Robincat and dog) “Gentlemen, please! After all, this dump is no ordinary joint! Leave us not turn it into a fight-aroma!”

LikeLike

Oh, and I thought this was a really good one:

(serving supposed mouse knuckles to Robincat) “Well, better late than forever! To phrase a coin! Sink your bicuspidors into this feast for sore eyes!”

😉

LikeLike

It even has Clarence “Jeff” Muse, the Seventeenth Doctor? I wonder if it was really him preventing awful occurrences from being seen on screen, and the Hayes Office is only the cover story.

LikeLike

I just read the Wilde story. My favorite part may be how he describes the protagonist’s determination to commit murder, with a completely straight face, as an example of his exceptional level of common sense.

LikeLike

“You don’t want anybody else to have any loving, just because you haven’t got any!”

And of course even though “We love each other so much!” the customer couldn’t possibly “have any loving” with her partner while wearing a dress that isn’t new.

LikeLike

Well, it’s not like their relationship is based on personality.

LikeLike