“Do you know what it means to feel like God?”

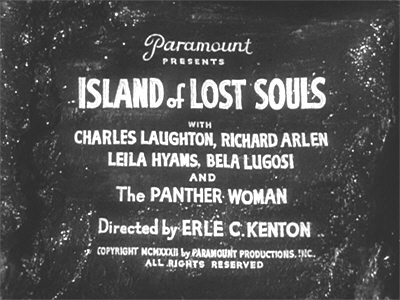

Director: Erle C. Kenton

Starring: Charles Laughton, Richard Arlen, Kathleen Burke, Leila Hyams, Arthur Hohl, Bela Lugosi, Stanley Fields, Paul Hurst, Tetsu Komai, Hans Steinke

Screenplay: Waldemar Young and Philip Wylie, based upon a novel by H. G. Wells

Synopsis: Castaway by the sinking of his ship, Edward Parker (Richard Arlen) is rescued after several days lost at sea by the crew of a South Seas trader. When Parker recovers from his delirium, he finds himself in the care of a man called Montgomery (Arthur Hohl), who concedes wryly that he was a doctor—once. He agrees to send a cablegram for Parker. In Apia, Parker’s fiancée, Ruth Thomas (Leila Hyams), has barely heard of the sinking of the Lady Vain before the cablegram arrives to inform her of Parker’s rescue by the Covena and his safety. Regaining his strength sufficiently to walk the deck, Parker is disturbed both by the ship’s cargo of wild animals, and by the strange appearance of its crew. One of the men, M’Ling (Tetsu Komai), accidentally spills some of the animals’ slops over the feet of Captain Davies (Stanley Fields), and is brutally struck down for his error. When the disgusted Parker verbally chastises him, Davies strikes at him too, but Parker knocks him down. He then kneels beside the recovering M’Ling—only to recoil from the sight of his hair-covered, pointed ear… Montgomery hurries Parker back to his cabin, warning him to stay out of sight. He does until the ship’s arrival at an unnamed island, where the animals are to be unloaded and given over to a man named Dr Moreau (Charles Laughton). Though obliged by sea-law to carry Parker on to Apia, the brutish Davies takes his revenge by literally throwing him off his ship, forcing Moreau and Montgomery to allow him onto the island. However, Moreau tells Parker that, the following morning, Montgomery will skipper the island’s schooner and carry him to Apia, as he wishes. Once arrived at the island, Montgomery remarks quietly to Moreau that he will stay overnight on the schooner with Parker; he is dismayed when instead, Moreau insists upon taking Parker up to his house. On the walk from the docks, Moreau reminds Parker that he is an uninvited guest; he adds that he should be cautious while on the island, and requests that he remain silent about what he sees once he leaves, to both of which Parker agrees. On the walk up from the docks, Moreau must use his whip to drive away more of the strange-looking men, who Parker now assumes to be the island’s natives. Moreau’s “house” is in fact a compound built into the jungle, with high, gated walls. Parker tries to discuss the natives, some of whom work as servants inside the gates, but Moreau ignores him, showing him instead to a room where he can wash before dinner. After the meal, Parker is disturbed by a weird howl from somewhere outside. Moreau reminds about his promise of silence, and warns him not to leave his room. Montgomery is then sent to do some work in the laboratory, while Moreau enters the room of a lovely young woman named Lota (Kathleen Burke). He tells her that a man has come from the sea; that she may go to him, and talk with him—but that she must avoid three subjects: Moreau himself; the Law; and the House of Pain…

Comments: While Universal naturally dominates any consideration of “the Golden Age of Horror”, the lesser yet vital role played by Paramount in the evolution of screen horror should not be overlooked. The studio stood somewhat apart from its fellows in the early 1930s, displaying neither Universal’s defiant enthusiasm for the burgeoning genre, nor the reluctant acquiescence of MGM and Warners. Instead, there was a tendency to observe developments from a safe distance—and then to toss into the mixture an occasional production calculated to outdo its rivals via an explosion of deliberate shock.

Thus, though Universal essentially created the horror genre with Dracula and Frankenstein, 1931 closed with Paramount’s version of Dr Jekyll And Mr Hyde, a superior production in every respect and thematically as daring as any film of the era. And then, in 1932, when MGM threw up its hands and produced Freaks in a declared attempt to make “something more horrible than all the rest”, Paramount retaliated with Island Of Lost Souls: a staggering mixture of horror, violence, sex and blasphemy based upon H. G. Wells’ novel, The Island Of Dr Moreau.

Though we tend these days to think of Wells admiringly as one of the fathers of science fiction, he was also a social theorist who embraced frightening schemes for the ultimate “improvement” of mankind via eugenics, culling of “the unfit” and “inferior”, and the repression of the individual for “the greater good”.

First published in 1896 (and revised in 1924), The Island Of Dr Moreau uses a science-fiction framework to illustrate what Wells viewed as some of the problems with contemporary society and the inherent shortcomings of Homo sapiens that were, in his opinion, hindering its proper progress. A correct reading of the novel requires the understanding that, in Wells’ view, Moreau is not “mad” – on the contrary – and that his experiments, if doomed to failure, are not wrong in themselves. Conversely, the reason that the novel’s hero, Edward Prendick, is so unsatisfactory is that he wasn’t intended as “the hero” at all, but rather as an example of the kind of wishy-washy liberal humanist who was holding society back, by encouraging the self-interest of the individual.

Whether those tasked with adapting the novel to the screen missed Wells’ point, as so many have, or whether they just didn’t care is debatable. Either way, the completed version of Island Of Lost Souls managed, while retaining the broad framework of the novel, to turn every one of the author’s points on its head, while also giving to the world a Dr Moreau who pretty much redefined the expression “mad scientist”.

It is not surprising that H. G. Wells hated the film, describing it as a “travesty” of his novel: something he meant quite literally; and he responded with open satisfaction when the film was banned in England.

In fact, Island Of Lost Souls was doomed to become one of the most censored films of its era, right alongside – you guessed it – Freaks. It could almost be said to gather momentum in this respect, after a curiously soft passage during its production.

Paramount had done the right thing in the first place by sending the novel to Colonel Jason Joy, then head of the Screen Relations Committee, the body given the thankless task of trying to enforce the Production Code in the days before a seal was necessary; Joy had responded with a stern warning about certain aspects of the book, in particular the suggestion of “crossing animals with human”; adding that if Paramount had any idea of including such material in their film, they should abandon it, as, “I am sure you would never be permitted to suggest such a thing on the screen.”

Not only did Paramount have such an idea, they went on to build their entire film around it. Astonishingly, when the completed script was resubmitted Joy demanded only one small cut before approving it to be filmed—and even backed down when Paramount argued that the line in question was necessary in delineating the extent of Moreau’s hubris. And even more astonishingly, when the film was ready to be released, James Wingate, Jason Joy’s replacement at the Screen Relations Committee, responded to it with enthusiastic approval—demanding no cuts at all, but warning that some states would undoubtedly object to that one same line of dialogue…

Wingate vastly underestimate the general reaction to Island Of Lost Souls. At this time each American state did indeed have its own censorship board, and the film was trimmed in a variety of ways in a variety of places, according to local sensibilities; being particularly harshly handled in Pennsylvania and Kansas.

This was nothing, however, compared to what it suffered overseas – including in Australia – where the film was cut literally to pieces; while it was banned outright in about a dozen countries, including (somewhat ironically, we might be inclined to feel) Germany. In England, there was practically nothing in the film to which the local censors did not object; and they spurned Island Of Lost Souls altogether with the brief but comprehensive complaint that it was, “Against nature.”

(To which we can hardly refrain from responding, “Well, duh.” Or as Elsa Lanchester, aka Mrs Charles Laughton, wryly put it, “Sure; so is Mickey Mouse.”)

But even in its censored form, Island Of Lost Souls proved problematic. Many critics blasted it, and there were frequent stories of horrified viewers walking out, or sitting with their hands over their eyes for much of the screening. Ultimately, the film was nowhere near the hit Paramount had hoped for: the studio had gone too far, both in terms of physical violence and the sexual implications of the material. Even the eventual revolt of the beast-men failed to touch a chord with Depression-era audiences, who conversely had responded enthusiastically to the oppressed and exploited zombies of White Zombie.

Over the following decade, Paramount tried three times to re-release Island Of Lost Souls; but after the enforcement of the Production Code, it was not until the film was eviscerated, with all of Moreau’s motivation and most of his actions removed, that the studio succeeded. Decades later, prints running approximately an hour made it into general circulation; but it was not until 2011 that the film underwent a proper restoration, in preparation for its release on DVD by Criterion.

Thankfully, then, we are now in a position to appreciate the sheer audacity of Paramount’s original production—but also to understand what upset people so much in 1933. This is, indeed, a confronting film, with moments that remain jolting even today.

Island Of Lost Souls begins briskly, with the rescuing of Edward Parker from the upturned dingy which saved his life, after the sinking of his ship. It is soon evident that the screenwriters have repositioned Moreau’s island to “the South Seas”, then the ocean equivalent of “Darkest Africa”. (Wells, with obvious intent, positioned Moreau’s domain in the vicinity of the Galapagos Islands.) Coming to, Parker finds himself being cared for by a man called Montgomery, who was once a doctor—until (as Moreau later reveals) a professional indiscretion put him in risk of arrest. Montgomery agrees to send a cable for Parker to his fiancée, Ruth, who is waiting for him in Apia, where they are to be married: a detail that places Island Of Lost Souls on the long list of 30s horror movies that deal with the disruption of the relationship between a near- or newly-married couple.

Of course there are no women – wholly human women – in the novel; but as we discussed with reference to The Most Dangerous Game, it was standard procedure at this time to shoehorn a female character into every Hollywood production, no matter how thankless the resulting role. And indeed, the role of Ruth is fairly thankless—more interesting for what is – nearly – done to her, than for anything she does, and as a yardstick, representing as she does the film’s one real note of normality. It is likely, I think, that Paramount cast Leila Hyams chiefly for her name value, to cash in on her much more prominent appearance in Freaks.

Ruth has barely had time to absorb the shock associated with the sinking of the Lady Vain than she receives the reassuring cablegram, telling her of Parker’s survival and his intent to be in Apia on the 6th of the month.

As it turns out, this prediction proves overly-optimistic. When Parker is well enough to walk the decks, he is disturbed to discover the nature of the “cargo” being carried by the Covena: a variety of caged wild animals; a pack of hounds; and a crew consisting of men who all seem to carry some sort of deformity.

All the animals seen in Island Of Lost Souls are real with one inevitable exception: the “gorilla” is played by Charles Gemora, hot off his similar appearance in Murders In The Rue Morgue. Fortunately, however, this is the only scene in which he appears; so that his patently fake ape-suit has no chance to damage this film as it does the other.

On the other hand, the film’s animal casting leads to many distressing scenes of frightened lions, tigers, wolves and hyenas thrashing around in small cages. (Animal-lover Charles Laughton was particularly disturbed by this aspect of the production.) It was not the animals alone who suffered, however: an extra, playing one of the beast-men, was badly mauled when the tiger managed to get one of its paws between the bars of its cage.

Just as repellent to Parker is the Covena’s drunken, brutish captain, Davies—although he is inclined to agree with the man’s furious repudiation of his cargo. Davies is not in the least placated by Montgomery’s contention that “cargo is cargo”, but launches into a tirade about, “An island without a name, an island not on the chart”:

Davies: “Dr Moreau’s island—and it stinks all over the whole South Seas!”

Montgomery counters this by arguing stiffly that Moreau is, “A great man and a brilliant scientist.”

At this moment, Montgomery’s servant, M’Ling, comes forward carry a bucket of slops meant for the dogs. Davies, still on the rampage, threatens to strike M’Ling who, in recoiling, spills some of the slops over Davies’ own feet. The captain promptly knocks M’Ling down, to Parker’s disgust. His verbal protest draws Davies rage to him, but his drunken swing misses; Parker puts him down with one well-delivered blow.

Parker then kneels beside the stricken M’Ling—but his concern turns to apprehension when he notices M’Ling’s ear, which is both covered in hair and pointed at the top. His feeling only increases when M’Ling, sitting up, first shakes himself like a dog, then launches at Davies with a deep growl, showing off an excellent set of canines in the process. Montgomery quells him, however, and sends him away; he also urges Parker to get out of Davies sight, and stay there until they land.

He does so, only emerging to watch with interest the unloading of the animal cargo and the strange crew onto a schooner piloted by a man dressed all in white: a man whom the mate, Hogan, confirms is Dr Moreau.

As the boats prepare to separate, Davies makes his move—striking the unwary Parker and tossing him bodily off the side of the Covena; he lands roughly on the deck of the schooner. Davies laughs uproariously as he orders his vessel away…

Moreau, as it turns out, is almost as appalled by this turn of events as Parker; though after a moment’s thought he reassures the dismayed young man that, in the morning, Montgomery can take him to Apia in the schooner.

This scene offers our first look at Charles Laughton as Moreau, and we know immediately we’re in for something special. Dressed all in white, carrying both a whip and a gun (the latter positioned suggestively in front of his groin), and with a wicked little goatee (the latter, the actor’s own idea), Laughton’s Moreau is a provocatively Mephistophelean creation.

Island Of Lost Souls was Charles Laughton’s third starring role in America, the follow-up to his outrageous Nero in DeMille’s The Sign Of The Cross—and, amazingly, an even more outré creation. If, as has been argued, the power of (for example) Laughton’s performance as Javert in Les Miserables came from him tapping into the self-loathing with which he struggled all his life, his Moreau represents the opposite end of the spectrum, those moments when he was able to indulge and enjoy his own idiosyncrasies.

Though the character as written is quite daring enough, Laughton’s interpretation is both genuinely shocking and blackly humorous, full of touches that hint at all sorts of unspeakable perversions—that is, in addition to the ones that Moreau is quite up-front about.

Moreau’s comment that he can provide a crew for Parker’s journey to Apia focuses his, and our attention, on the men’s strange boat-mates, milling together at the far end of the deck—all of them, like M’Ling, seemingly with some sort of facial deformity. Several of them press around the caged gorilla, speaking to it in lowered voices, and until Moreau orders them angrily to get away from it. Two of the more brutish-looking ones are singled out for our notice by being addressed by name: Ouran and Gola.

Though purely the result of practical makeup effects, the “beast-men” of Island Of Lost Souls are an effectively unnerving presence. Particularly praiseworthy is the variety observable amongst the group: though similar in their slouching posture and shuffling gait, the beast-men evince a range of heights and builds; as well as differing in their features, their skin-tones, their degree of body-hair, and the nature of their individual “deformities”. Even in scenes such as this, where there is no particular emphasis upon these points, the viewer is invited to speculate about the origins of each; their mass appearance in the later crowd-scenes makes a disturbing impact.

Meanwhile, the location scenes in Island Of Lost Souls were filmed around Catalina, and the fog which swathes the island so atmospherically during the arrival of Moreau’s schooner was quite real, much to the delight of director Erle C. Kenton and art director Hans Dreier. However, Moreau’s compound, a kind of art-deco fortress built in and around a rioting jungle, was entirely the result of Dreier’s genius; one clever detail has a vine-wrapped tree branch draped across the compound, a curving structure that offers a walkway up to the first floor of the main house. The other behind-the-scenes star of Island Of Lost Souls was cinematographer Karl Struss, whose gorgeous black-and-white photography is full of beautiful and sinister shadow effects, particularly bars and zig-zags of dark and light.

Upon arrival at Moreau’s dock, the crew begins uploading the animals. Montgomery offers to spend the night on the schooner with Parker, and is appalled when Moreau instead invites him up to the house. Moreau waves aside Montgomery’s muttered protest that Parker has already seen too much, commenting that, “I have something in mind…”

Before they step out into the surrounding jungle, Moreau reminds Parker rather grimly that he is an uninvited guest: urging him to do as he is told while he is at the house, and demanding his promise that he will stay silent after he leaves the island about anything he sees; to which Parker agrees.

During their walk to the house, Moreau and Parker are followed by a number of the island’s residents, who Moreau drives away with expert cracks of the whip with which he is never without. When they pass through the high iron gates, however, Parker sees that several of them are employed inside as servants, a fact which only adds to his growing discomfort.

“Strange-looking natives you have here,” Parker finally observes in what might be the understatement of 1933. Moreau’s off-kilter response is to offer Parker a cold shower (!).

Moreau, Montgomery and Parker dine together in the latter’s assigned room. At the end of the meal, though he speaks jeeringly of Montgomery’s taste for spirits, Moreau intervenes to stop him drinking too much and orders M’Ling to clear the table. His doing so is interrupted by a moaning cry from somewhere outside, which provokes a trembling fit in the white-clad servant. The men then separate, Moreau departing with an admonition to Parker not to leave his room.

Outside, Moreau reveals to the horrified Montgomery his plan to introduce Parker to someone he calls “Lota”…

Not only in the addition of Ruth Thomas to the scenario of Island Of Lost Souls did the film depart from its source—but also far more memorably, in the character of Lota. At a casual glance this is the standard blonde / brunette, good-girl / bad-girl scenario—but as was also the case with Paramount’s Dr Jekyll And Mr Hyde, this cliché arrangement is turned into something startling.

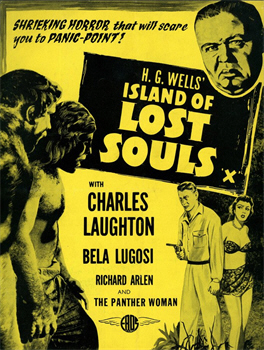

The main way in which Paramount drummed up pre-production publicity for Island Of Lost Souls was via a hunt for a “Panther Woman”: young women were encouraged to show just how feline they could be, with a trip to Hollywood and a film contract the ultimate prize. No less than 60,000 entries were received, which were winnowed down to four finalists—and a final, slightly unlikely choice made of shy nineteen-year-old Kathleen Burke.

Paramount, it should be noted, followed through on their promises—in fact giving all four finalists a shot in Hollywood; though only Gail Patrick really went on to a significant career. Kathleen Burke, though she later appeared in a couple of major films, including Henry Hathaway’s The Lives Of A Bengal Lancer and Dorothy Arzner’s Craig’s Wife, struggled to break out of B-movies, and retired from the screen after a career of only six years. It is generally believed that the “Panther Woman” publicity stunt and the subsequent promotion of Burke under that title did her a great deal more harm than good: she was treated as a studio creation, a bit of advertising art, rather than respected for her talent.

But – and there could hardly be a more significant “but” – BUT – Burke started her short screen career with an incredible one-two punch, following up Island Of Lost Souls with her appearance in Murders In The Zoo, as the wife of a deranged Lionel Atwill. You could hardly have two characters more different, yet each in its own way is memorable and tragic—indicating depths of talent in Burke that, sadly, film-makers of the time rarely tapped. Without her, Island Of Lost Souls would not linger in our memories as it does, the dominating impact of Charles Laughton notwithstanding.

Having parted from Parker, Moreau orders Montgomery to the laboratory – “You’ll see what has to be done,” he comments, adding that he kept him sober for this reason. Moreau, meanwhile, has other fish to fry…

Remarking that Lota is terrified of himself and Montgomery (understandably, as the latter concedes), Moreau allows himself to speculate on what her response will be to Parker, who she has no reason to fear:

Moreau: “Will she be attracted? Is she capable of being attracted? Has she a woman’s emotional impulses?”

Indeed—the introduction of Lota marks this film’s passage into an area so outrageous in its implications, it almost defines the pre-Code era. What is staggering is how explicit the film is: not bothering with hints or allusions, but telling the audience almost in words of one syllable what Moreau is up to, and the implications of that for Parker. Granted, the film has not yet revealed the origins of the island’s “natives”; but when the reveal does come, there is no getting away from the fact that this is, in essence, a film about bestiality; that its entire plot turns upon the possibility of human / animal sex. The only thing more thoroughly shocking is Moreau’s smirking delight in the situation he has created.

Island Of Lost Souls’ introduction of Lota is intriguing, a subtle inversion of James Whale’s famously confronting three-shot introduction of the Creature in Frankenstein. She is shot from behind, so that the audience sees only her tousled hair, and hears only her soft voice saying, “Yes”, to each of Moreau’s orders. Having seen the other “natives”, the viewer is prepared for the worst: instead Lota turns out to be a lovely if exotic-looking young woman (Kathleen’s Burke’s makeup exaggerated to emphasise her eyes and cheekbones), whose every movement is charged with a sinuous grace.

Before taking her to Parker, Moreau gives Lota a last firm command: she may talk to him about anything, with three exceptions: she must not mention him, Moreau, she must not mention the Law, and she must not mention the House of Pain…

(This is the film’s first use of that now-infamous expression.)

Parker is understandably startled by his unexpected introduction to a young woman, who Moreau comments is, “Pure Polynesian”, and the only woman on the island. He then leaves – or seems to – in fact spying on the two through a barred section of the wall.

There is a painful quality to the little scene that follows, both Parker and Lota going through the social rituals according their separate training. Though their conversation goes nowhere, Lota is intrigued by Parker – “the man from the sea,” as Moreau has explained him – and quite willing to cosy up.

However, just as things are getting interesting, Moreau is summoned away by an urgent Montgomery who, swathed in gown and surgical mask, calls him to the laboratory.

Parker and Lota are still making awkward conversation when they are interrupted by an agonised scream. Parker is alarmed, but Lota recoils in terror; and so frightened is she, she forgets the most serious of Moreau’s interdictions, gasping aloud, “The House of Pain!”

Though Lota tries to hold him back, Parker rushes out and to the laboratory—where he finds Moreau and Montgomery standing over a humanoid figure which is chained to a surgical table, and writhing and groaning in agony. “Get out!” snarls Moreau. “Get out!”

Sickened, Parker does. As Montgomery closes the laboratory door behind him, Parker staggers towards Lota. “They’re vivisecting a human being,” he says in numb disbelief. “They’re cutting a living man to pieces!”

“Vivisection”, that is, the use of live, often unanaesthetised animals in medical and surgical research, was a hot-button issue when H. G. Wells wrote The Island Of Dr Moreau, and it remained one when this film was made. (We should note, however, that the term was and is often applied to any animal experimentation, of any kind.) A burgeoning animal-rights movement took on the medical profession over it and a protracted battle ensued, eventually producing an increasingly stringent set of laws and requirements for licensing around all animal experimentation.

The creation of the beast-men is another widely misunderstood aspect of The Island Of Dr Moreau. Wells believed that an over-concern with pain was one of the main things holding back the advancement of human society, which could only progress via the acceptance of suffering by the masses (which, naturally, excluded Wells himself). Moreau’s indifference to the agonies of his surgical subjects therefore marks him as one of the few with the capacity to lead humanity forward. The implication of his experiments is that, using animals, a way might be found to rid mankind of its “animalistic” tendencies; the failure of those experiments indicates how strong is man’s connection to his “beast” past, and how much there is to overcome before progress could be made.

Wishy-washy Edward Prendick, meanwhile, though initially sickened, becomes immured to the pain of the beast-men as his disgust with them grows; he eventually admits (in typical humanist style) that other people’s pain only really bothers him if he has to look at it. In other words, it’s not about them, but about his own comfort.

But none of that applies in Island Of Lost Souls, wherein Moreau’s experimentation marks him as madder than a hatters’ convention.

Parker’s first thought, as he reels away from the laboratory, is that if Moreau can experiment on a man in the first place, he’ll probably do it on any man. Grabbing Lota, he runs from the compound and out into the jungle, towards Moreau’s schooner and safety.

The fugitives don’t get far, however. Soon they find themselves on an edge overlooking a clearing in the jungle, where many beast-men are gathered around a fire. Catching sight of Parker, several of them cry, “Man from sea! Man from sea!”

Parker and Lota turn to run, but find their way blocked by Ouran and Gola, who have followed them from the compound. Parker strikes at them with a fallen branch, before he and Lota turn back the other way—and find themselves surrounded…

“Stop!” cries a familiar voice. “Stop!”

It is hard to know what to make of Bela Lugosi’s appearance in Island Of Lost Souls as the Sayer of the Law—if you can call it an appearance, given that Lugosi is buried under a welter of fake fur. The harsh reality was that, by mid-1932, Lugosi had blown both the professional and financial gains of his success in Dracula: he was bankrupt, and trying to win his way back to the studio favour he had lost through his subsequent pickiness over roles; particularly his rejection of the Creature in Frankenstein. His acceptance of this relatively minor, if quite memorable, role marked a new, hard-learned compliance on his part; while for Paramount, they took the opportunity offered of another “name” for their film at a bargain price. And like so much of what Lugosi did, what he does here is memorable for its oddness, rather than because it is good. (It doesn’t help that he gets the film’s silliest beast-man makeup.)

The beast-men surge around Parker and Lota: the former is again referred to as “man from sea”. Then comes some argument as to whether the intruders are “like us” or “like them”.

“One is not man,” observes the Sayer, leering at Lota.

The sound of a gong interrupts this dangerous moment. On the ridge behind stands Moreau, whip in hand…

At the sound of the gong, all the beast-men pour obediently into the clearing. They stand still and silent as they gaze up at Moreau, who demands of them, “What is the Law?”

This is another point at which the novel has been inverted: Wells intended his law as a mockery of the Ten Commandments, seeing religion as another barrier to human progress; his beast-men are taught the law by an interfering missionary in an attempt to give these not-quite-humans an ethical code to live by, and Moreau finds it a damned nuisance. Here, it is a code invented by Moreau himself, to keep the beast-men in line.

Nevertheless, the “call-and-response” ritual that follows is clearly meant to carry religious overtones, be they ever so twisted, with the chanting beast-men all kneeling down before their whip-cracking “Creator”:

What is the Law? Not to run on all fours: that is the Law. Are we not men?

What is the Law? Not to eat meat: that is the Law. Are we not men?

What is the Law? Not to spill blood: that is the Law. Are we not men?

His is the hand that makes. His is the hand that heals. His is the House of Pain…

Moreau raises his whip, his face wreathed in a smile both contemptuous and gloating: the mad scientist as God…

…a point which Moreau not only concedes, but revels in, when subsequently explaining himself to Parker—both out of necessity of the moment and because, we see, he is absolutely dying – not to justify himself; he sees no need for that – but to boast about his own brilliance.

Parker, we soon realise, has completely misunderstood what he has seen on the island: he thinks Moreau is taking the natives and turning them into subhuman part-beasts. This gives Moreau his opening—allowing him to reveal that each and every one of the beast-men has been constructed out of some sort of animal…

The science of Island Of Lost Souls is both broadly correct and profoundly wrong. Moreau speaks offhandedly of “stripping away evolution”, referencing plastic surgery, transplantation, blood transfusion, gland extracts, ray baths and alterations to “the germ plasm” in the construction of his beast-men. While allusions to such techniques place him (if you’ll pardon the expression) at the very cutting-edge of contemporary knowledge, of course the uses to which he puts his techniques are entirely impossible—whether they be animal / animal transplantation, the creation of the ability to speak, or alteration of the brain to “permit” advanced thought and learning.

Also wrong – though in this belief, Moreau is hardly alone – is the film’s presentation of evolution, which embraces the most widely-held misconceptions about the theory: namely, that it is a more-or-less linear process leading to the improvement of the species; and that Homo sapiens represents some sort of “pinnacle”, towards which all other species are striving. In this we find a fundamental misunderstanding of the difference between best and fittest: evolution is not about making anything “better”, but about giving it the tools needed for survival within a particular environment. Homo sapiens is merely a species well-adapted to current conditions—no different, in that respect, from the cockroach.

This lengthy scene, in which Moreau reveals himself to the simultaneously repulsed and fascinated Parker, is the highlight of Island Of Lost Souls—not least because of the bizarrely funny way in which Charles Laughton plays it. And some of it is very funny, including a distinctly phallic pair of giant asparagus spears, the outcome of one of Moreau’s early plant experiments. Yet the humour only underscores the horror of much of what Moreau is saying, and the chilling contrast between Moreau’s candid delight in his own proceedings and the misery he has inflicted along the way.

Horror does finally overwhelm the note of burlesque, however, first via Moreau’s complete indifference to the agonies of the beast-man-in-the-making, still chained to the operating table, as he pokes it and prods it and inspects his own progress, and then in his casual dismissal of what he calls, “Some of my less successful experiments”—discarded beast-men who, in chains, work the treadmill of the island’s electrical generator.

As with all the best genre movies, Island Of Lost Souls has plenty of subtext to go along with its text; and while the surface horrors alone offer plenty of food for thought in terms of medical responsibility and transgression, and the nature of humanity, it is also possible to put broader social readings on the film—with Moreau, as interpreted by Charles Laughton, easily envisaged as the face of colonialism and/or slave-owning, in in his brutal and self-serving exploitation of the disadvantaged.

And these readings are underscored by Moreau’s verbal response to his brief contemplation of his failed experiments, musing that, which each experiment, he gets nearer his ultimate goal:

Moreau: “Do you know what it means to feel like God?”

…which was the one line Colonel Joy wanted cut after he read the script – we can only wonder what on earth he didn’t see in the rest of it!? – and even then he backed down in the face of Paramount’s counter-arguments; perhaps because the line was presented as a rhetorical question, a matter of feeling like God rather than being God—as opposed to the flat-out statement we now associate with Henry Frankenstein. (Similarly, Charles Laughton’s soft-voiced reading is a million miles away from Colin Clive’s hysteria.)

Overall, Moreau is staggeringly frank to Parker about his work—but there is one thing he does not tell him. While discussing the challenges involved in giving his beast-men the ability to talk, the doctor descends to a sexist joke: “Someday I’ll create a woman, and it will be easier.” Yet the implication behind this cheap crack is self-evident: Moreau has no intention of telling Parker that he has already created a beast-woman…

After Moreau has sent Parker of to bed with a sardonic, “I hope you sleep well”, he watches on as Lota, who has been hovering out of concern for Parker – she is not used to people coming out of the House of Pain as they went in – stops him to say a quiet goodnight. Moreau is delighted, crediting Lota with being, “Tender, like a woman”:

Moreau: “How that little scene stirs the scientific imagination onward! I wonder how much of Lota’s animal origin is still alive; how nearly perfect a woman she is…”

And of course—Moreau intends to find out, with the unknowing assistance of Parker. Montgomery here points out that there isn’t much time for this, um, experiment: Parker will be leaving in the morning—

—except he won’t, because when they get to the dock it is to find that someone has damaged and partially sunk the schooner overnight. Moreau is profuse in his regrets…

Meanwhile, the Covena has finally arrived in Apia. A bewildered Ruth tries to get some information about Parker, who is nowhere to be found, and is finally directed to Captain Davies. He refuses to answer her questions, and is belligerent in the face of her threats to report him to the American consul—although a lot less belligerent when actually summoned into his presence. Davies finally confesses Parker’s whereabouts, and the latitude and longitude of Moreau’s island. The consul assigns a Captain Donohue to carry Ruth to the island and retrieve Parker.

Back on the island, we find Lota’s fascination with Parker growing stronger—not surprisingly, as the only human being ever to be kind to her. In a marvellously constructed scene, she literally slinks into his presence and curls up beside him; and – in perhaps my favourite moment in the entire film – Parker responds with a light caress that amounts to him scratching Lota behind the ears; and if she doesn’t purr in response, well, it’s only because Moreau has robbed her of the ability to do so.

Lota wants Parker to talk to her rather than read; and when he explains that books might help him get off the island, she snatches the current one out of his hand and throws it into a nearby pond. (We are given a gorgeous shot here of the two of them reflected in the rippling waters.) Parker misinterprets her actions, and rather belatedly confesses, “I’m in love with someone else.”

“Love?” queries Lota, as she cuddles up to him. She probably only wants to be stroked; she ends up getting kissed…and as Parker then puts her aside, his face showing confusion, it is left ambiguous whether it is thoughts of Ruth that stopped him, or if sensed that something was wrong.

Lota follows him, however, and throws her arms around him—and this time when Parker puts her away from him, it is because of the pain he suffers when she digs into his back with—not her nails, but her claws…

Lota gasps in distress, as Parker – shocked, horrified, repulsed – backs away from her in dawning understanding…

Bursting in upon Moreau – who calmly continues his tea-making – Parker denounces him; drawing a curious distinction between Lota and the rest of the beast-men, which he declares are “horrible enough”; she, however, has been given, “A woman’s emotions, a woman’s heartbreak, a woman’s suffering.” Prepared to keep his promise of silence over the others, Parker now warns Moreau that, once back in the world, he will expose him.

Except, of course, that Parker is going nowhere, as Moreau quietly reminds him.

Moreau then proceeds to tell Parker all about the one thing he kept from him previously, the creation of Lota—“My most nearly perfect creation.” There was a reference earlier to Moreau being hounded out of England, after an experimental dog escaped from his London laboratory. He now reveals the vision that has sustained him through his eleven long years on that island, that of returning to London in triumph…

In this, Laughton’s Dr Moreau sets the pattern for a long, long line of spurned movie scientists, each and every one determined to vindicate their work and “prove the fools wrong”. But with the casting of Lota as Moreau’s prize exhibit, it becomes impossible not to see Island Of Lost Souls as a twisted version of Pygmalion – or My Fair Lady, if you prefer – given Moreau’s evident plan to pass off on London society no mere Cockney flower-girl, but a walking, talking Panther Woman.

(It should be noted that, though Kathleen Burke is listed as “the Panther Woman” in the credits, as well as all over the film’s advertising art, never at any point in the film is a panther or any other animal mentioned in context of her creation. Perhaps this was one of those weird censorial touches, wherein you could get away with something as long as you didn’t spell it out.)

But Moreau’s plans for Lota go well beyond that, as he reveals to Parker with amusing obliviousness to his growing rage and indignation; very personal rage and indignation:

Moreau: “I wanted to prove how completely she was a woman; whether she was capable of loving, mating, having children…”

(The thing that always surprises me in that line is the frank use of “mating”, rather than a euphemism.)

“You see of course the possibilities that presented themselves,” concludes Moreau—and gets a long-overdue fist in the middle of his tea-sipping face.

Typically, Moreau takes his anger at his disappointment out on Lota—who, in a tragic mockery of her true nature, is found examining herself in a mirror, which sits behind a table covered with perfume bottles and other women’s items. When Moreau demands to know how Parker found out the truth, poor Lota silently holds out her hands. Moreau drags her over to the window, so in natural light he can examine those revealing claws; twisting her fingers brutally as he turns her hands this way and that.

Montgomery enters to find both Lota and Moreau slumped despondently on a settee. “The stubborn beast flesh creeping back,” sighs Moreau (a process quite as impossible as the reverse, of course). “I may as well quit.”

But even as he speaks, there is a sob from beside him. In dawning realisation, Moreau grabs Lota by the hair and ruthlessly twists her around so that he can see her face. “The first of them all to shed tears!” he whispers. “She is human!”

(In fact, many animals can and do cry; but it is still up for debate whether they shed tears for emotional rather than physiological reasons. Most scientists think not, and are extremely wary of anthropomorphisising animal behaviour; though it is difficult to dismiss evidence such as an elephant crying after the death of its offspring, as has been observed.)

And seeing that Lota is so close, so very close to being the “perfect creation” he envisaged, Moreau is determined to take her all the way—via the House of Pain:

Moreau: “This time I’ll burn all the animal out of her!”

And as if all this wasn’t shocking and confronting enough, Island Of Lost Souls follows up with my nomination for the most outrageous line of dialogue of the pre-Code era:

Moreau: “I’ll keep Parker here. He’s already attracted. Time and monotony will do the rest…”

Not just bestiality, then, but voluntary bestiality, with knowledge aforethought—good grief! As with so many films of this era, particularly it seems genre films, about a dozen different writers were involved in the development of the script for Island Of Lost Souls, including the ubiquitous Garrett Fort; but in the end it was credited to Philip Wylie and Waldemar Young—the latter of whom was Lon Chaney’s main screenwriter, for The Unknown among other films. (It shows.)

But alas! – well, I suppose we’re obliged to say so – this is of course the signal for the forces of normality to re-assert themselves, and they arrive in the form of Ruth and Captain Donohue. Anchoring their boat off the coast of the island, the two row themselves to the dock. One of Moreau’s servants, the little pig-man, sees the new arrivals, and rushes off to tell Gola about them—one of them in particular: “Man! One not man! One like Lota!”

The journey of Donahue and Ruth to the compound is punctuated by glimpses of Gola and Ouran, both straining to get a look at “the one like Lota”. However, a disagreement over “dibs” ends in a violent fight, and Gola takes a beating.

There is more trouble up at the house, when Montgomery discovers – in what might just be another motion-picture first – that someone has been tampering with the island’s one radio-transmitter. Meanwhile, the pig-man alerts M’Ling to the arrivals, and he, faithful as always, reports to Moreau.

(In the book M’Ling and the faithful dog-man that Prendick adopts are two different creations, but the film blends them.)

Montgomery then recalls the wire he sent for Parker from the Corvena, and realises who the arrivals must be. Moreau meets them at his gates – which he does not immediately open – noticing the way that Ouran peers from the bushes at Ruth.

He then begins playing the good host, inviting Ruth and Donahue in—and looking on again as Ruth and Parker embrace and kiss. As this is going on, Moreau calls Ouran inside the compound:

Moreau: “I may not need Parker…”

As Moreau avoids making small-talk with Donahue, and Parker shows Ruth into the house, a shattered Lota looks on—fully aware of the implications of Ruth’s arrival.

But Moreau has overreached himself: the worm is about to turn. Having sat still through eleven years of mad experimentation, and even through the planned “mating” of Lota and Parker, Montgomery draws the line at what Moreau evidently has in store for Ruth.

The first sign of his rebellion is his promise to Lota that there will be no more House of Pain—not for her, at least.

Parker wants to leave the island at once, but Moreau works on Donahue and Ruth, emphasising the dangers of the jungle after dark, and offering them accommodation for the night. Since Parker can’t insist without explaining, and since he remembers only too clearly his night-time encounter with the beast-men, he gives in. A most uncomfortably silent dinner follows; more uncomfortable when not silent, though, as the conversation turns to “long pig”. Donahue drinks freely, but Montgomery – to Moreau’s surprise and displeasure – declines altogether.

Distant sounds of the beast-men chanting reaches the diners; presumably the Sayer of the Law is trying to quell the disturbance caused by Ruth’s presence. However, Ouran is not amongst those being reminded of the demands of the Law, but is still lurking within the compound. Moreau, meanwhile, is prompted to offer what be yet another first, overtly with respect to “the natives”, but in fact with reference to Ouran, who we see peering through some bars at Ruth:

Moreau: “They are restless tonight!”

When the party separates for the night, Parker doubles up with Donahue, while Ruth is given a room of her own—which just happens to be the one near which that trailing tree-branch in the courtyard ends up leaning. Parker urges Ruth to lock her door, misjudging the direction from which the threat will come. As Ruth begins to undress, Ouran stares at her from the shadows…

As Ruth sleeps, Ouran scuttles up the branch and begins to exert his strength upon the bars of her window. The noise wakes her—and her hysterical screaming brings Parker, who can’t get in because her door is locked. He does, however, shoot through the grill, driving Ouran away.

Meanwhile, this is the final straw for Montgomery, who lets Moreau know very clearly that he knows what he intended, and that he, Montgomery, has finally had enough; too much. Even Moreau’s reminder that he is a wanted man in England has no effect upon him. (In the book, the inference is that Montgomery is homosexual, and wanted for a “crime” far other than medical malpractice.) He throws in his lot with the others, urging them to brave the dangers of the jungle, which at this point are clearly less than the dangers within the compound.

Donahue volunteers to go alone to his ship and fetch his crew, insisting over Ruth’s protest that he has faced far worse in the past; he has a gun, and Montgomery gives him a torch and a key to the gates. Moreau watches Donahue leave, and calls Ouran to him—ordering him to catch up with Donahue, and dispose of him. Even the brutish Ouran initially shrinks from this, muttering, “The Law?”

“It’s all right tonight,” Moreau assures him…

The effect is muted here, but there is finally the suggestion that the beast-men have been convinced that real men, those wholly men, cannot die (possibly this subplot got lost in the rewrites). At any event, once he has followed Moreau’s orders and strangled Donahue, Ouran carries the body back to the encampment and tosses it into the midst of the gathered beast-men. The effect is stunning: not only has the Law been broken, blood spilled – “Law no more!” retorts Ouran, when the Sayer accuses him – but now the beast-men see that men like Moreau can die; that Moreau can die…

Hilariously, the beast-men now show the extent to which they have been civilised: before storming the compound as a mob, they stop to arm themselves with lighted torches…

Only the loyal M’Ling declines to join the revolt, instead rushing to Moreau to warn him—and subsequently dying in his defence.

Back at the house, Moreau correctly interprets the clamour of the beast-men—inquiring innocently of the others, “Where is Captain Donahue?” But perhaps he fails to interpret its implications for himself…

The others, however, do not: Montgomery, Parker and Ruth head for the back entrance to the compound—only stopping long enough for Parker to collect Lota. The four run through the jungle—not realising that Ouran is stalking them. Lota, however, does realise it: she drops back, hiding from the others, and then glides up into the branches of a tree. As Ouran passes underneath, she pounces…

The vicious battle kills both of them, Ouran dying with Lota’s claws embedded in his throat. The battered Lota lives just long enough to speak a few parting words to Parker…

It the terms of the time, it had to be, of course; but—dagnabbit.

(That said, I prefer this ending for Lota to the cop-out of the Don Taylor version.)

Moreau himself is perversely delighted at the uprising. So confident is he of his power over his creations, he goes out to meet his fate—striking the gong and cracking his whip as usual, and demanding to know, what is the Law?

“Law…no more!” responds the Sayer; while Ouran outs Moreau: “He tell me, spill blood!”

Despite the savagery of the whip, the beast-men surge forward, driving Moreau back to the compound. There, their tormentor at bay, the beast-men cry out their approval as the Sayer denounces Moreau for making them, not men, not beasts, but merely—things. “Part man! Part beast! Things!” they howl as they rush towards him—Karl Struss’ camera catching a series of close-ups of the individual beast-men that must have been shocking in 1933; as well as, notoriously, one particular beast-man who has a cloven hoof.

(Unconfirmed rumours have Alan Ladd and Randolph Scott – the latter having been considered for the role of Parker – among the beast-men; certainly there were John George, Buster Brodie, Schlitze Surtees – the microcephalic from Freaks – and Charles Gemora, picking up a second paycheque. The rest were a collection of bit-actors, stuntmen, wrestlers and extras.)

Finally realising that he has been betrayed by his hubris, Moreau tries to retreat into the compound, but the beast-men catch him before he can lock the gates. As they surround him, pressing him back against a wall, he tries one last, desperate feint:

Moreau: “Have you forgotten the House of Pain!?”

No. No, they haven’t…

Although – as with Freaks at MGM – Island Of Lost Souls proved a disappointing overreach by Paramount at the time of its first release, it is a film whose reputation has grown over time—and rightly so. This is a film quite breathtaking in its audacity; and if its subject matter does not shock as it once did, it retains the ability to startle the viewer—if only in a, “I can’t believe this was made in 1933!” kind of way. Perhaps no other film so thoroughly illustrates film-making before the Production Code; or why the Production Code was finally enforced the following year.

Though others would later turn to H. G. Wells’ novel, Island Of Lost Souls remains unique for its blending of mad science, perverse sex, black humour and genuine pathos. The “normal” cast-members are all fine if unremarkable; but the beast-men linger in the memory; while Charles Laughton and Kathleen Burke between them create something marvellous. Burke is genuinely touching as the tragic Lota; while with his capacity for cruelty, his unabashed enjoyment of his work and the sheer insanity of his methods, Laughton’s Moreau raised the bar for all mad scientists to come.

Want a second opinion of Island Of Lost Souls? Visit 1000 Misspent Hours – And Counting.

Footnote: While I had a cogent reason for mentioning My Fair Lady in-text, the other film-thought that always comes to me while watching Island Of Lost Souls I left for here, out of respect.

The first time I ever saw this film, I had an inappropriate laughing-fit when Ruth arrived to “rescue” Parker from the terrible prospect of having sex with Lota—because suddenly all I could think about was Lancelot “rescuing” Galahad from the Castle Anthrax, in Monty Python And The Holy Grail.

Seriously, can’t you imagine Ruth and Parker having exactly this conversation?—

“We were in the nick of time. You were in great peril.”

“I don’t think I was.”

“Yes, you were. You were in terrible peril.”

“Look—let me go back in there and face the peril.”

“No, it’s too perilous…”

♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦

This review is for Part 1 of the B-Masters’ 20th anniversary celebration!

Pingback: Mad science, you say? « The B-Masters Cabal

Reblogged this on Mike's Movie & Film Review.

LikeLike

I saw the remake of this with Michael York, where they changed the ending to leave out the woman showing her bestial origins coming back. I reread the novel after that, and to be honest, I didn’t pick up on all the subtext you read. What gave me chills (and would really make a horror movie) was the description of what the hero did after Moreau was killed. He lived for months in the jungle with the beast-men and beast-women (none of whom would be mistaken for human). After he was rescued, he lived in torment with the impression that the people around him were actiing the same as the beast-men, parroting their lines without thought or intelligence.

Now that’s horror.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I should stress that those interpretations are not so much subtext as a reading based on my knowledge of Wells’ social theories. We tend to assume that we’re supposed to condemn Moreau but the text is neutral.

I do find some support for my view in the fact that we’re left with Prendick’s disgust with mankind, as you mention. This is one of those novels with a whole chunk of narrative that no film maker has bothered with.

LikeLike

your little fingers have been busy, haven’t they?

You realize, with all your comments, I have to go back and read all those reviews again, AND all the comments, Thank you!

My impression of Dr. Moreau’s motivation is just, “Hey, let’s see if this will work”. He says, “To this day, I have never worried about the ethics of the matter.” He made a faceless Thing, just as an experiment, which got loose and killed before it was killed. He wasn’t trying to prove anything, really. He stuck to the Human form as his goal just for standardization – no matter what the animal was to begin with, he wanted them all to be as close to human as possible. “But the stubborn beast-flesh grows day by day back again.”

LikeLike

Well, it’s about time.

Um…you’re welcome?

I think Moreau is trying to work out how to progressively transfoem animal ti human in preparation for the day he will eliminate the remaining animal from the human…

LikeLike

Laughton also played the monstrous father in The Barretts Of Wimpole Street: getting as close as they dared to the “a little more then kin and less than kind” implications of the horrible relationship between Elizabeth and her dear old dad. As Laughton put it, “they could censor the script, but they couldn’t censor the twinkle in my eye.”

While bestiality is of course grotesque in the extreme, what’s really upsetting today is the realization that if Moreau had had his way and brought Lota back to London, there’d be plenty of men lining up for a “made to order” cat-girl. The feminist implications alone are bone-chilling. Nowadays we work out this problem in Sci-Fi with robots and androids, but the realization that many, many people of both genders would be just fine with a created lover/sex object that has all the ‘tears of a woman’ and none of the rights of a human being hasn’t gone anywhere.

LikeLiked by 3 people

That’s another role, like his playing of Javert, where Laughton taps into his self-loathing.

It isn’t only his relationship with Elizabeth that’s icky, it’s the distinction he makes between her being “born of love” and the others being “born of {censored}”. I know that’s in the play but I’m always startled by how much of that material they were allowed to keep in the film.

You mention androids in this context, I immediately think of TNG’s “The Measure Of A Man”, of course. (And later Voyager’s “Intellectual property rights for holograms!” plot. 🙂 )

But yeah, because of our broader and franker context, that’s an aspect that’s only become more horrifying with passing time.

LikeLike

Laughton really had an issue with bad fathers: look at Night of the Hunter, his sole film directing credit. Talk about subtext giving way to plain ol’ text!

LikeLike

Even before I read the review, that first poster… “sure, honey, she lured me on, it wasn’t my fault…”

Ah, if I had a pound for every time some SF film or series says “they’re more highly evolved than us”… you know what’s more highly evolved than you? A koala that can only eat eucalyptus.

LikeLike

I can’t remember what it was actually for – I suppose I’ve blocked it – but for a while we had an ad campaign here that featured the line, “Don’t just be the fittest, be the best you can be!” It drove me to frothing-at-the-mouth fury whenever it played.

LikeLike

I saw this some years back, and I remember being struck by how frightening Moreau’s subjects were. Seemed really shocking for a 1932 film.

This might make an interesting double feature with Cocteau’s Beauty and the Beast…gorgeous fantasy versus grotesque realism.

LikeLike

I don’t think Legosi gets enough credit for his Speaker of the Law role. His doleful roars of “ARE WE NOT MEN?” really underline the horrific nature of Moreau’s vision.

LikeLike

Yes, the makeup work is nastily effective. (As always, the B&W photography helps.)

The ending of La Belle Et La Bête always ruins it for me…

The combination of the voice and the makeup tends to distract from the performance, though on the other hand they underscore the self-disgust in his later cries of, “THINGS!!”

LikeLike

“a Dr Moreau who pretty much redefined the expression “mad scientist”.”

I’m not sure I understand what the previous definition of “mad scientist” was, then.

LikeLike

I’m mad, MAD I tell you! Look at the cost of these medical supplies! Are there no reputable evil contractors anymore?!

LikeLike

There had been a misapprehension that Henry Frankenstein represented the limits of scientific madness… 🙂

LikeLike

Hmm. So the 1933 version was torpedoed by the censors and the disastrous production and subsequent flop of the 1996 version with Marlon Brando is so legendary that they made a documentary about it. Maybe the story is cursed. How did the Micheal York version fare?

LikeLike

Seems to have vanished without trace, neither good enough to be memorable nor bad enough to be memorable.

LikeLike

Pretty much. They eliminated all the shocking material and seemed to be trying to make Planet of the Apes: Spring Break. It’s like it’s fading off the screen as you watch.

LikeLike

I caught it a few months ago, and it added the twist where Moreau did try to make York an animal. He grew hair in all sorts of strange places. But he still had his intelligence, which he demonstrated by reciting childhood memories. Which made Moreau really mad.

Everybody on the island dies, except for York and the girl. York’s hair disappears after a few days, right before they’re rescued. I heard that the original ending was to have the girl start to show her bestial origins (the animals always reverted after a few days without treatment). Which would have been rather shocking for an ending.

LikeLike

It came out in the summer of 1977. Largely overshadowed at the time as another little SF film by a relative nobody famous for directing American Graffiti.

LikeLike

Some of your comments about the novel contradict what I remember from it, but maybe the version released in the USA slightly differs from the original. Besides, you’re more likely to be right about that and, well, pretty much anything, what with being a SCIENTIST and all…

😉

LikeLike

Why thank you. 😀

No, as I said to Dawn up-thread, it’s a reading of the novel based on Well’s social theories, rather than anything overt in the text.

LikeLike

I think the Brando Moreau’s deal was that he was trying to prove that combining a human and an animal would create a human-like being with the “innocence” (i.e. the whole “never known sin” perspective) of animals, so that instead of “corrupting” animals he’d be “purifying” human beings. One can guess how well THAT would’ve gone over with Wells…

LikeLike

Pingback: The Most Disturbing Moments From Classic Horror Films - Weird Darkness