Officer 444 (1926, 10 episodes)

Robert Preston Brownley (Ben Wilson) – “Uncle Bob” to the children of his precinct, and Officer 444 to his colleagues – is the a member of the “Flying Squadron” under the command of Captain Jerry Dugan (Lafe McKee). The squadron’s main task is to break up a dangerous criminal gang, and to determine the identity of its mysterious leader, known only as “the Frog”. When scientist Professor Haverly (Arthur Beckel) perfects his new formula for “Haverlyite”, the Frog and his gang are so determined to gain possession of it, they set fire to the chemical plant where the formula was developed. In the ensuing confusion, the gang gains possession of a sample of Haverlyite. Officer 444 bravely enters the burning factory and rescues the trapped Professor Haverly, but he later dies of his injuries, leaving his son (Phil Ford) the only person who knows the secret of Haverlyite. Knowing that they can use Haverlyite for all sorts of nefarious purposes, the gang kidnaps young Haverly—but Officer 444 is hot on their trail… Unfortunately, Officer 444 fails to live up to the promise of its first episode—and that’s putting it mildly. Star Ben Wilson, who also produced, was fifty when he cast himself as the “dashing young policeman”; it goes downhill from there, with most episodes consisting almost entirely of chases and arm-flailing fist-fights, and a perfunctory cliffhanger at the end. Absurdly, the Frog favours a disguise both conspicuous and hindering, shuffling along under the joint “affliction” of a hunchback and an unnerving glass eye; while apparently we’re not supposed to realise that a second character, who sports an obvious Groucho glasses / eyebrows / moustache outfit, is disguised. Neva Gerber, aka Mrs Ben Wilson, is nurse-heroine Gloria Grey, who contributes nothing to the action besides getting kidnapped a lot, but is allowed to tag along with the police like the Kenny in a Japanese monster movie. Ruth Royce does better as “the Vulture”, one of the Frog’s “subtle aides”, whatever that means (no-one helps in this serial, they all “aid”), although her main job is simply to hang onto Gloria while the men flail their arms. The one genuinely amusing touch in Officer 444 is the Dragon Cafe, a front for the Frog’s gang, where Bright Young Things like to Charleston the afternoon away oblivious to the kidnappings, fights and arrests going on around them; the serial’s one genuine point of interest, that August Vollmer – first Chief of Police of Berkeley, where this was filmed, and one of America’s first professional criminologists – appears as himself. It was Vollmer who first established a motorised police-force, and Officer 444 accordingly puts much emphasis on the squadron tearing to the scene of various crimes in their cars (although it must be said that these scenes have a weird Keystone Kops-y vibe). This serial apparently also features the first-ever onscreen use of a polygraph—or as it was known at the time, a “lieing machine”. Officer 444 was directed by Francis Ford, who was also responsible for its “scenario” (a way of saying there was no screenplay as such; it shows); Ford’s son Phil gives a one-note performance as Haverly Jr. We should note that, entirely typically for this sort of serial, the audience is never told what Haverlyite actually is.

(I’m in two minds as to whether the funniest touch in this serial was an off-colour joke they got called on, or an accident they hurriedly corrected: one subplot deals with an organisation called the “Amalgamated Society of Scientists”; by the next episode, it is the “International Society of Scientists”.)

The 9th Guest (1934)

Based upon The Invisible Host by Gwen Bristow and Bruce Manning, also known as The Ninth Guest. Eight prominent New Yorkers are summoned by telegram to a party held in a penthouse apartment. As they begin to assemble, tensions rise, as they discover amongst themselves a high degree of enmity. Corrupt politician Tim Cronin (Edward Ellis) has ruined the chances of his main rival with the help of his lawyer, Sylvia Inglesby (Helen Flint), much to the fury of man-behind-the-throne, Jason Osgood (Edwin Maxwell). However, Cronin’s glee is tempered by the exclusion of his debutante daughter from society, after her shunning by hostess Margaret Chisholm (Nella Walker). Meanwhile, Osgood has forced university dean, Dr Murray Reid (Samuel S. Hinds), to dismiss academic Henry Abbott (Hardie Albright) on the grounds of his supposed radicalism. The last guests, actress Jean Trent (Genevieve Tobin) and journalist / author James Daley (Donald Cook), are childhood sweethearts who fell out over a willed property meant to bring them together. The prevailing hostility lifts to another level, however, when the eight guests hear themselves addressed by a disembodied voice, informing them that they have been brought together to play a game of wits—in which the losers will die… Though it gave rise to both a film and a fairly successful play, the novel The Invisible Host by the husband-and-wife writing team of Manning and Bristow is all-but forgotten today, except for something that may or may not have been an accident: its odd resemblance to one of Agatha Christie’s most famous works—usually known these days as And Then There Was None. On the whole I’m inclined to think this was a coincidence – the novel itself was never issued in Britain, nor the play staged there; though I suppose this low-budget B-movie may have been screened – but even if it wasn’t, there is no question that Agatha’s work is immeasurably superior. Unfortunately, having come up with such a brilliant premise, the authors of The Invisible Host wasted it on a silly thriller full of elaborate death-traps and other such improbable devices, in which there is nothing more weighty at stake than petty personal revenge. The 9th Guest follows its model too well to be anything but an amusing time-waster, with all extraneous matter trimmed away as it rips through the novel’s cycle of accusation and sudden death over a brisk sixty-five minutes. (It does find time and space for an Odious Comic Relief butler, alas…) Though the “invisible host” who addresses his guests from time to time via a hidden speaker insists that the eight have been summoned for “a battle of wits”, personal animus and panic soon dominate the gathering as, per the host’s grim promise, one of them dies each hour. Attempted murder leads to unintended self-killing; suicide follows the revelation of a disgraceful secret; while a fatal shooting out of terror leads to a second suicide. When a shot in the dark leaves another participant dead, the survivors must pull themselves together in order to save their own lives and identify the guilty party… The best thing about The 9th Guest is the art deco apartment in which the action unfolds. The cast is generally undistinguished, with exception-to-the-rule Genevieve Tobin given disappointingly little to do as the film’s putative heroine.

The Case Of The Frightened Lady (1940)

Isla Crane (Penelope Dudley-Ward) is a poor relation of the aristocratic Lebanon family, who supports her widowed mother and two younger sisters by working as secretary to the autocratic Lady Lebanon (Helen Haye). Life at Mark’s Priory is becoming increasingly difficult for Isla, however: she is disturbed to discover that a lock has been added to the outside of her bedroom door, and frightened by the two unlikely “footmen”, Gilder (Roy Emerton) and Brooks (George Hayes), who take over the duties of the regular servants at night. Isla’s problems increase when Lady Lebanon tries to bring about a marriage between Isla and her son, Lord Lebanon (Marius Goring), who is the last of the family; but Isla is drawn to the young architect, Richard Ferraby (Patrick Barr), who is doing restoration work at the Priory. Lord Lebanon himself, meanwhile, is angered by the constant presence of Dr Amersham (Felix Aylmer), who seems to have some sort of hold over Lady Lebanon. When the family chauffeur, Studd (John Warwick), is murdered, the obvious suspect is the husband of the woman he was planning on running away with; but with the murder weapon a silk scarf of Indian origin, Inspector Tanner (George Merritt) isn’t so sure… Okay, pay attention: this British production is also known simply as The Frightened Lady, to distinguish it from the 1938 made-for-television version – that’s right, the British had TV during the 1930s; deal with it – of the same story, which was filmed as The Case Of The Frightened Lady; both of which were based upon a play by Edgar Wallace which was written as Criminal At Large but later had its title changed to The Case Of The Frightened Lady, and which had already been filmed in Britain, in 1932, as The Frightened Lady, but which in the US had its title changed to Criminal At Large. Got that? The main failing of The Case Of The Frightened Lady is something we’d normally consider a virtue, the lengths to which it goes to disguise its stage origins by opening up its action—which in this case leads to so much jumping from scene to scene and place to place, it becomes confusing and hard to follow. The film’s pacing generally is off, and there is a tendency to skimp on character introductions, with the result that, occasionally, someone gets killed off before we’ve properly grasped who they are. (The film-makers may have assumed, not unreasonably, that by 1940 everyone watching was already familiar with the plot.) Broadly speaking, this is standard Wallace stuff, with a killer on the loose in a house of secrets, police-procedural elements blending a little uneasily with hints of cults and insanity, and much ado about mysterious locked rooms, secret passages, and people creeping about in the dark. It’s reasonably good fun in spite of its shortcomings, if never for a moment credible. For all her prominence in the title, Isla Crane offers little to the plot, besides setting the general tone with periodic outbursts of hysterical screaming. In fact, despite the foregrounding of a tepid love-triangle, this film is dominated by its older cast-members – Helen Haye, Felix Aylmer, George Merritt – although Marius Goring has a few poignant moments as a young man trapped by his circumstances.

Footnote: If I were Penelope Dudley-Ward, I think I’d be getting legal advice over this:

City Of Missing Girls (1941)

Police Captain McVeigh (H. B. Warner) puts his retirement on hold in order to assist newly appointed Assistant District Attorney, James Horton (John Archer), in trying to solve a series of missing-persons cases—the latest of which has climaxed in the discovery of the dead body of missing dancer, Thalia Arnold. Horton is under extreme pressure for results, both from the District Attorney (Lloyd Ingraham) and from reporter Nora Page (Astrid Allwyn), whose paper is waging a campaign against his office. McVeigh believes that a local nightclub owner – and crime boss – King Peterson (Philip Van Zandt), is behind the disappearances. In fact, Peterson is using his silent partnership in a theatrical agency / training academy for aspiring artistes to gain access to lovely young girls, whose ambitions place them in his power. However, the situation is proving too much for the overt owner-operator of the agency, Joseph Thompson (Boyd Irwin)—who also happens to be Nora Page’s step-father… City Of Missing Girls is a well-meaning but unconvincing drama finally taken down by its mixture of mealy-mouthed-ness and peculiar characterisations. The former is to be expected, given the film’s production date; but even so, the presumed euphemism, “being sent to work as dancers in another city”, is not used euphemistically enough—leaving behind an odd suggestion that the missing girls really are working as dancers in another city. Meanwhile, Nora Page is just insufferable, even by the low-low standards of the “spunky reporter” trope, with her love-hate relationship with James Horton looking a great deal more like genuine hate on his part—and understandably so. (I was reminded of Otto Kruger’s attitude towards Marguerite Churchill in Dracula’s Daughter.) The performance of H. B. Warner as wily veteran police officer McVeigh nearly redeems the film – despite his being on the eve of retirement, I’m happy to report that McVeigh escapes the film with his life – while the screenplay offers just enough odd twists to keep it watchable, particularly with respect to Thompson’s “academy”: in fact, the film is much more interesting in its minutiae than its main plot. It also builds to a hilariously clumsy climax. (NB: If you’re planning on pleading self-defence, try not to be found standing over your unarmed victim with a gun in your hand seconds after you’ve shot him…)

The Bloody Brood (1959)

A group of beatniks falls under the sway of Nico (Peter Falk), whose nihilism goes so far as to encourage his companions to view the collapse and death of an elderly newspaper vendor as a form of “performance art”. Given access to the apartment of a friend, Nico invites the entire group for a party. When Francis (Ron Hartmann) sneers at what the rest consider “kicks”, Nico enlists him for a special venture… Teenage messenger-boy Roy (William Kowalchuk) calls with a telegram for the apartment’s owner. Nico tells him that Curtis isn’t there, and then invites him to join the party for a short time… Later that night, Cliff Bowers (Jack Betts) gets a frantic phone-call from Roy, who is in extreme pain; he collapses before he can tell his brother what happened to him. Nearby, Nico and Francis look on as Roy dies… Cliff is devastated by Roy’s death, and enraged when Detective McLeod (Robert Christie) tells him that Roy ate a hamburger laced with ground glass. When the initial police investigation exonerates both the eating-places on Roy’s route and the people to whom he delivered a message on the night of his death, Cliff persuades McLeod to give him the list of the addresses at which Roy called, to do some checking of his own. He soon discovers that although Curtis, who one of the undelivered telegrams was for, was not at his apartment when Roy called, a lot of other people were… This low-budget drama was the feature-film debut of director Julian Roffman, who cut his teeth as a wartime documentary-maker for the National Film Board of Canada. Though Roffman’s follow-up, The Mask, is probably better known to B-movie buffs, The Bloody Brood is an impressive if rough-edged production, whose shortcomings are compensated for by an uncompromising story-line, an unnerving central performance by Peter Falk, and some moody black-and-white cinematography (by Eugen Schüfftan!). The film is also quite confronting in its violence, pointing forward to the more exploitative films that would emerge during the 1960s. Thematically, however, The Bloody Brood is a world away from those later exploitation efforts: this is a profoundly conservative film, roundly condemning its out-of-the-mainstream characters while glorifying the Bowers brothers, for whom work and education is all there is in life. In fact, The Bloody Brood carries this theme almost to the point of dishonesty. The film is both disgusted by and contemptuous of its beatniks, even though – and this is perhaps the single most interesting thing about it – it admits that most of them are regular people with regular jobs, who simply choose this milieu and lifestyle as their way of blowing off steam. (Only Dave the goatee-ed poet is what we might call a “professional” beatnik.) Nico, meanwhile, is explicitly shown as an outsider who is using the beatniks to further his burgeoning career as a drug-pusher, and because they feed his ego by allowing him to assume leadership over them; and while the film might be justifiably critical of the latter, it never stops to ask why these people are so disaffected. Furthermore, it is because intellectual dilettante Francis sneers at the beatniks and the music, poetry, sex and drugs from which they are content to get their “kicks” that Nico enlists him in his thrill-killing scheme. (All of which begs the question of whether there has ever been a beatnik film that was actually about the beatniks? Even A Bucket Of Blood, which perhaps comes closest, is really about its outsider / wannabe.) Nevertheless, when Cliff Bowers submerges himself in the world of Nico and his followers, his curled lip expresses the view of Julian Roffman and his screenwriters. Discovering that Roy’s last call was during a party hosted by Nico, Cliff poses as a friend of the absent Curtis in order to infiltrate the group. Though he uses a false name, Nico and Francis discover the deception and realise that Cliff is Roy’s brother. Having from the moment of the murder’s commission been subsumed by guilt, Francis begins to go to pieces; but Nico responds with a campaign of escalating violence against Cliff…

Caesar The Conqueror (1962)

Original title: Giulio Cesare, il conquistatore delle Gallie (Julius Caesar, Conqueror Of The Gauls). The most interesting thing about this Italian historical drama is that it effectively gives Julius Caesar a screenwriting credit—declaring itself to be based upon his Commentarii de Bello Gallico (“All Gaul is divided into three parts…”, yada-yada). I haven’t read the book myself, and can only hope it’s a lot less dull than this film. Caesar (Cameron Mitchell) has already conquered Gaul when the film opens, and has his eyes upon Britannia. Back in Rome, however, those who oppose Caesar and fear his ambition are massing against him under the leadership of Pompey (Carlo Tamberlani). The film then devolves into a series of scenes amounting to the Senate saying, “Julius Caesar, you get back here to Rome right this minute!” and Caesar responding, “I won’t and you can’t make me!” While this is playing out, Caesar stages a series of gladiatorial contests to amuse himself and his troops, and is so impressed with one fighter, Vercingetorix (Rik Battaglia), that he rewards him with his freedom. This proves something of a mistake, as Vercingetorix promptly begins forging alliances amongst the various factions within Gaul and raises a rebellion against the Roman invaders. Meanwhile, Caesar tries to forge an alliance of his own by marrying his ward, Publia (Raffaella Carrà), to Quintus Cicero (Aldo Pini), the brother of the orator Cicero (Nerio Bernardi) and one of his most important generals, even though she loves Claudius Valerian (Ivica Pajer), a brave centurion. The plan becomes moot, however, when both Publia and Valerian are captured by Vercingetorix… Whatever its shortcomings as drama, there is no doubt that, overall, the makers of Caesar The Conqueror were striving for historical accuracy; so it is amusing to note that their courage failed them at the last, when they chose to conclude their film with a bloody battle between Caesar’s forces and the rebels led by Vercingetorix. In fact, the rebellion was put down by a brutally protracted siege; and while this wouldn’t have made for much of a climax, it would have been a more fitting ending for a film that is itself something of an endurance test. I may also say that watching this film with the weight of much drama and pepla behind it is a peculiar experience: you have to keep reminding yourself that it is Caesar who is the hero, and that the rebels are the bad guys. (Apropos, the German title of this film translates to “Caesar The Tyrant Of Rome“.)

Hellfighters (1968)

Chance Buckman (John Wayne) is the head of an international company whose specialty is dealing with oil-rig fires and similar dangerous situations. Though Buckman’s team are the best in the world at what they do, this has come at a personal price: Buckman’s wife, Madelyn (Vera Miles), unable to deal with the stresses of her position, left him many years ago; as a result, Buckman barely knows his now-adult daughter, Letitia (Katharine Ross). So guarded has Buckman been about his personal life that most of those close to him do not know about his family. However, when he is seriously injured on the job, Buckman’s friend and former colleague, oil executive Jack Lomax (Jay C. Flippen), sends word to Madelyn and Tish. The former is in Europe, but Tish flies in to see her father—meeting along the way Greg Parker (Jim Hutton), Buckman’s protege, to whom she is immediately attracted. After being reunited with her estranged father and assured of his recovery, Tish begins a whirlwind romance with Parker which ends in marriage. This brings Madelyn home: she is dismayed to find Tish following in her own footsteps, and even more so when she insists upon accompanying her husband on his dangerous assignments… Loosely based on the professional, if not personal, life of “Red” Adair, who acted as a consultant on the film, Hellfighters is a fair action movie (not a disaster film, alas) that falters whenever it strays away from the oil-fields. In broad terms the film somewhat resembles Harari!, in that it likewise deals with a team of men doing a dangerous job supremely well, and that much of its interest lies in the technical details of how exactly they go about it; the two films also share some cast members (Wayne, Bruce Cabot, Valentin de Vargas), and both spend much time pondering the “right” kind of woman for a man who does such work. Hatari!, however, is as much or more entertaining outside of its animal-trapping scenes; whereas Hellfighters offers only flimsily obvious characterisations and silly “male bonding” scenes of the kind that really should have gone out of fashion by 1968 (for example, bar-brawls in which people get thrown through glass and hit with furniture, but no-one ever gets hurt). Reasonably enough in context, I suppose, but still aggravatingly, the screenplay puts the onus for the maintenance of relationships entirely on the female partner, whatever strain or sacrifice that might entail—to the point that the separation of Chance and Madelyn due to the latter’s inability to deal with the stress of being a firefighter’s wife leads to her being condemned (by her future son-in-law, no less) as “a complete bitch”. On the evidence presented, however, the viewer is unlikely to feel that Tish’s penchant for intruding herself into her husband’s business at the worst possible moment is all that more desirable. Hellfighters is ultimately sustained by its fire-fighting scenes, which are on the whole convincingly staged; although the film would have been better off with more scenes of the firefighters planning their approach to their work, and less of Katharine Ross standing around looking worried.

Lady Caroline Lamb (1972)

William Lamb (Jon Finch) becomes engaged to the emotionally unstable Lady Caroline Ponsonby (Sarah Miles), to the dismay of his autocratic mother, Lady Melbourne (Margaret Leighton). Though initially the marriage is happy, it is not long before Caroline’s erratic behaviour begins to cause difficulties for her husband, particularly when his political career gains momentum. Caroline’s desire for the spotlight takes a new and dangerous turn when she encounters the aristocratic but poverty-stricken Lord Byron (Richard Chamberlain): she finds him intriguing, but hardly credits his claim for poetic genius. She is proven wrong when Byron becomes the rage of London society; and Caroline, like so many others, is swept away by his writing. When their paths cross again, it is the trigger for a passionate affair conducted with complete disregard for discretion or who might be hurt. Byron, however, soon grows weary of Caroline’s demands; and a cruel streak in his nature prompts him to humiliate her publicly. Caroline, however, cannot let go… The only film directed by screenwriter, Robert Bolt, and starring his wife, Sarah Miles, Lady Caroline Lamb is a well-mounted and interesting but historically questionable drama. The main problem is that, having taken a sympathetic stance towards Caroline, the film just prunes away anything that doesn’t happen to jibe with that reading—such as the lengthy feud / stalking that followed her breakup with Byron, and which included the publication of Caroline’s roman à clef novel about their affair, Glenarvon. Caroline herself was full of tics and dramatics, so Sarah Miles isn’t badly cast; but Jon Finch is given nothing to work with as William Lamb (the future Lord Melbourne, Queen Victoria’s favourite Prime Minister): while it is true that Lamb stood by his wife in spite of everything, the film never attempts to get at what he was thinking or feeling. Ultimately, it is the supporting players who have the best of things: Richard Chamberlain is a fittingly calculating and self-centred Byron; Laurence Olivier gives us an amusingly sardonic Duke of Wellington; John Mills appears as William Lamb’s political mentor, George Canning (another future Prime Minister); Michael Wilding makes a final, brief film appearance as Lord Melbourne; and his real-life wife, Margaret Leighton, steals the film as Lady Melbourne—whose own life was an object lesson in how to conduct sexual liaisons discreetly. Indeed, perhaps the best thing about this film overall is its ironic awareness that nearly all of William Lamb’s social and political advantages stem from the fact that his mother was once the mistress of the Prince of Wales. Speaking of whom, Ralph Richardson gives us a—well, I’m going to call him just “George”—who is both inappropriately slender and unconvincingly shrewd: the film refers to this character as “the king” and “George IV”, even though the events depicted took place when he was still Prince Regent; a strange and jarring blunder. In spite of its story inaccuracies, Lady Caroline Lamb offers a fine visual depiction of Regency England, including location shooting at Chatsworth, Brocket Hall and Wilton House.

Evil Under The Sun (1982)

Hercule Poirot (Peter Ustinov) is hired by Sir Horace Blatt (Colin Blakely) to retrieve a valuable jewel from actress Arlena Marshall (Diana Rigg), who not only jilted him to marry another man but, when he demanded his wedding-gift back, substituted a paste copy. Their pursuit of Arlena carries both men to the Adriatic, where Daphne Castle (Maggie Smith) has turned a gift from a grateful royal ex-lover into an exclusive island resort. In addition to Arlena, her new husband, Kenneth Marshall (Denis Quilley), and her resentful young step-daughter, Linda (Emily Hone), the guest include Myra (Sylvia Miles) and Odell Gardener (James Mason), Broadway producers whose potential smash-hit turned into a disaster when Arlena walked out on the show; writer Rex Brewster (Roddy McDowall); and Patrick (Nicholas Clay) and Christine Redfern (Jane Birkin). Already existing tensions rise when Arlena rejects Brewster’s plea that she authorise his biography of her, and when Redfern begins openly pursuing the actress, to the misery and humiliation of his rather mousy young wife. It is not, perhaps, altogether surprising when Arlena is found strangled to death on an isolated beach… Rewriting Agatha Christie just for the sake of doing it is nothing new, as demonstrated by this rather exasperating adaptation of her 1941 novel of the same name, which shifts its action from the English south coast to an island in the Adriatic Sea apparently just because it could, and which clearly put a lot more effort into its costume design and its Cole Porter soundtrack than its screenplay. Like all of these ensemble-cast productions, the focus was upon cramming as many names into the film as possible, with little consideration given to how that might damage the story: the character of Arlena Stuart Marshall was rewritten into a vehicle for Diana Rigg, and everything else falls apart from there. Only the Redferns bear any resemblance to their novel-counterparts, and there the film still goes wrong via the complete over-playing of both Nicholas Clay and Jane Birkin. Peter Ustinov was always a poor choice to play Hercule Poirot, of course, but this film, in the pursuit of the semi-humorous, turns Poirot not only into a buffoon, but a stereotypical Frenchman. The only person who comes out of this worse is poor Roddy McDowall, who suffered the indignity of being asked to play a stereotypical gay man! Sylvia Miles is terrible as the brash, chainsaw-voiced Myra; and in the end, only Maggie Smith, James Mason and young Emily Hone escape with their dignity intact. However—the bare bones of Agatha Christie’s plot are still buried beneath the overdone surface of Evil Under The Sun. Of course nearly everyone on the island had reason to want Arlena dead; but as it turns out, almost everyone on the island has an alibi, too—except for the late-arriving Sir Horace, the presence at the crime scene of the fake jewel proving that he did find an opportunity to talk, at least, to Arlena, despite his denials. But the more Poirot looks into the murder, the more he sees that it is a matter not merely of timing, but of expert timing; perhaps from someone who has done such a thing before…

(This adaptation of Evil Under The Sun not only eliminates the character who actually uses that biblical quotation in the book, but a short conversation about female depilation – or the lack thereof – which is one of the funniest things Agatha ever wrote.)

The Shooting Party (1985)

In the autumn of 1913, Sir Randolph Nettleby (James Mason) hosts a house-party at his country estate. Though on the surface a genial meeting of like spirits, tensions develop between several of the guests. For Lady Hartlip (Cheryl Campbell), the gathering provides an opportunity for a sexual liaison with the financier, Sir Reuben Hergesheimer (Aharon Ipalé), in tacit exchange for his payment of her gambling debts. Aware of his wife’s infidelities, the humiliated Lord Hartlip (Edward Fox) tries to console himself by dominating the shoot—only to find his reputation as his circle’s premiere sportsman under threat from the almost offhand excellence of young barrister, Lionel Stephens (Rupert Frazer). Lionel, meanwhile, is dismayed to find himself falling in love with Olivia (Judi Bowker), the young and sensitive wife of the much-older Lord Lilburn (Robert Hardy). A shortage of manpower forces Sir Randolph to order the hiring of Tom Harker (Gordon Jackson) as an extra beater, despite his reputation as a poacher and a political radical. But even more offensive to the guests than Harker is Cornelius Cardew (John Gielgud), an animal-rights activist who risks his life to disrupt the shooting… Based upon the novel by Isabel Colegate, The Shooting Party is the story of the sun setting—not exactly upon the Empire; not just yet; but upon the long Edwardian summer which preceded WWI. The story unfolds during one of the last of such traditional shoots: the following autumn, house-parties for casual mass-slaughter were a bit on the nose even for the British aristocracy. But while the coming war looms over every moment in this film, the action is carefully placed in another sense: it unfolds shortly after the passing of the Parliament Act 1911, which deprived the House of Lords of its traditional political veto power—to which the upper classes responded by clinging all the more tenaciously to their social privileges… This is a beautifully constructed and rather haunting film, which – like the novel – relies upon the audience’s fore-knowledge of the horrors to come across Europe: the viewer is reminded repeatedly that these were the people largely in charge of the bloodbath—a point driven home when the shooting party ends in tragedy. Unsurprisingly, this film’s sympathies are with its fringe-dwellers: young Marcus Nettleby, out of step with the self-centred adults; Ellen, the generous-natured maidservant; Harker, with his dark mutterings about David Lloyd George; the eccentric Cardew, exercising the courage of his convictions; and, oddly, Sir Randolph himself—a man constrained by his social position into going through all the appropriate motions, yet one with a far deeper if inarticulate understanding of, and interest in, the world outside his walls. This was James Mason’s final film, and it provides a fitting climax to a stellar career. In fact, the highlight of The Shooting Party is the encounter between Sir Randolph and Cardew which, while the other shooters fume, diffuses the potential for violence in the situation, while revealing the two as thoroughly decent and honourable men: each recognising this in the other. Watching two old pros like Mason and John Gielgud, at the end of their respective careers, playing so expertly off one another is both joyous and moving. At the other end of the spectrum, Rupert Frazer and Judi Bowker are a bit facile as the star-crossed young lovers; but that said, the cast is generally excellent. Of course, for all its social and political underpinnings, this is a story about a shooting party—and while they cannot be called gratuitous, the film does contain many lengthy and upsetting sequences of birds being slaughtered; although the cumulative effect of this is, at least to an extent, off-set by the unexpected resolution of the subplot concerning Marcus’s pet duck…

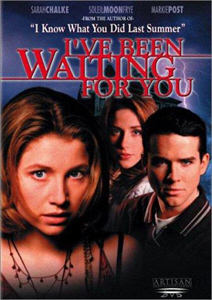

I’ve Been Waiting For You (1998)

Based upon a novel by Lois Duncan. Sarah Zoltanne (Sarah Chalke) moves with her mother, Rosemary (Markie Post), from Los Angeles to the small New England town of Pinecrest, where they have rented a large, rambling old house. Left alone to unpack while her mother buys dinner, Sarah has a series of unnerving experiences: the sudden appearance of a black cat; a loss of electricity; and the ringing of a phone that, moments before, was not working. When Sarah answers it, a voice whispers: “I’ve been waiting for you…” At school, Sarah’s sharp tongue, her interest in the occult and her idiosyncratic wardrobe marker her as an outsider and bring her into conflict with a clique who call themselves “the Descendants’ Club”. However, she makes a friend in Charlie (Ben Foster), who works part-time in a local bookstore that also sells more esoteric items, such as crystals and incense. She stands by Charlie when he is the victim of bullying, and resists the attentions of Eric Garrett (Christian Campbell)—not least because of the rage of his girlfriend, Kyra Thompson (Soleil Moon Frye). Sarah soon learns that the house which she and her mother occupy has a notorious reputation: three hundred years before, a young woman, Sarah Lancaster (Laura Mennell), was dragged from it in the middle of the night and burned as a witch. This story takes on a deeply personal aspect for Sarah when she discovers that a curse was placed upon the witch-hunters; that the members of the Descendants Club believe her to be the reincarnation of the witch, come back for revenge; and that they intend to do it to her before she can do it to them… If I’ve learned anything from I Know What You Did Last Summer – actually, I’ve learned a LOT; but that’s a story for another time – it’s not to blame Lois Duncan for what is done to her books when they’re translated to the screen. I’ve Been Waiting For You fits this paradigm perfectly: what ought to be a respectable, if wholly predictable, supernatural thriller-cum-teen angst drama suddenly transforms into – or rather, becomes as well – a post-Scream (and post-IKWYDLS) teen-focused slasher movie, with a suspiciously familiar hooded and masked figure running around killing people with a set of home-made Freddy Krueger-esque metal claws (that is, when they don’t just die of fright upon being attacked, as happens in one intensely lame cop-out moment intended to avoid graphic bloodshed). The result is a confusing mish-mash of elements that tends to lose track of what it’s actually about. I may say I was not at all surprised to learn that no such killer features in Duncan’s novel, Gallows Hill, which instead concerns itself simultaneously with Sarah’s torn feelings over going her own way or trying to fit in with “the cool kids”, and the rather more urgent matter of her possible connection to a vengeful Sarah Lancaster. Whatever the book may have done, I’ve Been Waiting For You fails to make either of these main plot-threads work. Sarah’s sudden compliance in pursuit of popularity is unconvincing, while the “Descendants” – a bunch of entitled prats who treat their “club” like an exclusive fraternity, rather than a defensive alliance against supernatural vengeance – are impossible to take seriously, and even leave us questioning whether we’re really supposed to—for instance, when they get confused over whether a witch thrown into water is supposed to sink or float. This film also offers one of the stupidest Spring-Loaded Cat moments I’ve ever come across; albeit one balanced by the black cat in question surviving the witchcraft plot. For the individual viewer, whether I’ve Been Waiting For You works at all probably comes down to how they feel about Sarah—who, whether she is or is not the reincarnation of Sarah Lancaster and/or the cloaked killer slashing his or her way through Pinecrest, or whether she’s just an upstart newbie trying to steal Eric away from Kyra, is clearly in a lot of trouble…

Footnote: Ah-HA! – that’s what genre this confusing film belongs to! – the white-people-staring-into-the-camera genre!—

Tomie: Replay (2000)

Technically the first sequel to Tomie, which was based on Itō Junji’s manga about a girl who will not stay dead no matter how often she is killed, was 1999’s Tomie: Another Face. However, that is not really a feature-film but three TV-episode adaptations of aspects of the manga, which were later cut together into a single production. That being the case (and since Another Face isn’t available here anyway), I allowed myself to skip to the first true film sequel. Tomie: Replay begins with a shocking and gruesome sequence, in which a child is hospitalised with a grotesquely swollen abdomen. As she is prepared for surgery, a scan reveals what appears to be a human face… As Dr Morita Kenzō (Sugata Shun) is making an incision, the girl’s abdomen convulses, causing him to cut his own thumb with the bloodied scalpel. He proceeds—only to start back in disbelieving horror as an eye peers at him from within his patient… Some time later, a young doctor called Takeshi (Matsuo Masatoshi) stops to talk to his friend, Sato Fumihito (Kubozuka Yōsuke), who is also a patient in the hospital. He comments on the recent rash of resignations, which has left the hospital understaffed, as well as the strange disappearance of the hospital’s director, Dr Morita. While Fumihito is hurrying away from his bed to use the bathroom, he catches a glimpse of what seems to be a naked girl; the same girl approaches Takeshi, begging him to take her away… Dismissed by the police when she tries to get information about her missing father, Morita Yumi (Yamaguchi Sayaka) goes to the hospital to question Kinoshita Atsuko (Togashi Makoto), a nurse who she knows was once her father’s mistress. Though Atsuko cannot help her, Yumi encounters Dr Tachibana (Endō Ken’ichi), the only remaining member of the surgical team that treated the young girl. He gives her Dr Morita’s medical journal—and then kills himself in front of her. The journal describes the strange surgery and hints at an even more bizarre aftermath. Its later pages, which are soaked in blood, make repeated reference to someone called “Tomie”—insisting that she is a monster who must be killed… Like Tomie itself, Tomie: Replay is something of a mixed bag. On the plus side it offers a far more coherent narrative than its predecessor, and makes less assumptions about the viewer’s familiarity with the manga—although in that respect there are still one or two moments oblique enough to be confusing. It also increases the gore quotient and the bizarre imagery, with an emphasis upon body-horror and severed heads in particular more appropriate to its source. However, the film never really lives up to the promise of its grotesque opening sequence; and despite its memorable visuals its overall tome is rather muted, with some of the acting low-key to the point of invisibility. Replacing Kanno Miho in the title role, Hosho Mai has her moments but is ultimately less effective; her “evil” laugh, in particular, is forced and annoying. Tomie: Replay also makes Tomie herself something of a side-issue by structuring itself as a mystery, with its focus upon the characters’ investigation into the strange and disturbing events that have suddenly impacted their lives. Separately, Yumi and Fujihito begin a search for someone called “Tomie”: the former because of the journal, the latter after a phone conversation with Takeshi during which he grows angry and threatening, insisting that Tomie is his. When the two cross paths, Yumi confides all she knows to Fujihito, who joins her in trying to discover what happened to her father. Meanwhile, having manipulated Takeshi into taking her home, Tomie is disappointed to discover that he is so easily “broken”. She proceeds to orchestrate her own murder and dismemberment by playing on the shy young doctor’s intense jealousy of Fumihito’s success with girls, before driving him insane by regenerating herself in front of him… Tomie then sets her sights on Fujihito and Yumi as more worthy prey—but underestimates the former’s strength of will, and the latter’s capacity for trust and forgiveness…

The Pentagon Papers (2003)

This made-for-TV movie is a fair retelling of the story of Daniel Ellsberg and his leaking to the press of the so-called “Pentagon Papers”. It follows him from his most hawkish days at the RAND Corporation through to the dismissal of the charges against him in the wake of the burglarisation of his psychiatrist’s office by the White House “plumbers”—tracing too his shattering disillusionment and growing rage upon discovering the secret manoeuvring of four consecutive presidential administrations with respect to Vietnam. Though Ellsberg was apparently not consulted by the film-makers, this seems a fair-handed presentation of events—balancing “the people’s right to know” against the nature and magnitude of Ellsberg’s actions. Of course, the real story is of Ellsberg’s progressive loss of faith in the government, and his resulting personal journey from patriot to traitor—or, depending upon your point of view, from patriot to greater patriot. This story was not an easy one to tell, as a way had to be found to convey Ellsberg’s inner turmoil, in a situation that necessarily precludes him from confiding in anyone; and the film resorts to various talking-head inserts, with Ellsberg discussing his feelings with his psychiatrist. Ultimately, these sequences are less of an issue than the amount of time that the screenplay spends on Ellsberg’s private life, and in particular his relationship with his second wife, when there were other aspects of the story far more imperative—though perhaps these did not sufficiently concern Ellsberg himself for the producers’ liking. Still, I would have liked more time spent on the legal aspects of the case, particularly the Supreme Court ruling over the freedom of the press to print what Ellsberg was providing. The Pentagon Papers is necessarily dominated by James Spader’s performance as Ellsberg, which is adequate if not brilliant. The film also stars Claire Forlani as Patricia Marx, Ellsberg’s supportive second wife; Paul Giametti as Anthony Russo, Ellsberg’s former RAND colleague who facilitates his copying of the stolen documents; Alan Arkin as Harry Rowen, then-President of the RAND Corporation ; and Kenneth Welsh as Secretary of Defense John McNaughton.

(In this digital age, perhaps the most impressive thing about The Pentagon Papers is seeing the document in paper form…)

Scream Bloody Murder (2003)

The senior class of Cherry Mount Academy – all five of them – are boarding the school bus prior to attending an end-of-year dance at the nearest boys’ school when they are joined by a new transfer student, Monique (Anna Garcia Williams, aka Anna Florence). The others – Goth-chick Star (Nicole Andris), bitchy Parker (Brittany Montgomery, aka Stephanie Northrup), sex-crazed Honey (Priscilla Ross), trust-fund brat-cum-closeted lesbian Candy (Missy Weinger), and virginal Shay (Gloria Balding) – are initially suspicious of Monique, but she wins them over with her coolness. Before the group sets out under the supervision of the repressed and nervous Miss Beaver (Tara Thomson), they have their phones confiscated by Principal Burden (Michael McConnohie), who warns them about their behaviour and reminds them they are representing the school. The outing starts badly when the driver, Beaumont (Drew Droege), backs the bus into a statue—unbeknownst to him, severing the vehicle’s fuel line. Consequently, the bus eventually runs out of petrol, leaving the group stranded in the middle of the desert. They are rescued by local tow-truck driver Hank (Jonathan Sayres), who takes them to his junk-yard—which has no phone. The girls’ frustration and boredom soon turns to fear, however, when it becomes gruesomely evident that there is a killer on the loose, intent upon picking them off one by one… Well. Had I known this was a horror-comedy – a slasher-movie spoof, rather than a slasher movie – it wouldn’t have made it into my rental queue; but as it is, I’m not sorry I watched it…mostly. Scream Bloody Murder did its best to alienate me at the outset: the first five to ten minutes are completely puerile, in a way that does not in the least make it clear that you’re watching a bad movie parody rather than a flat-out bad movie; and overall it suffers from dead spots and too much repetition, the latter necessary to drag out the running-time. But it settles down after its teeth-clenching opening—leaving me mildly entertained by most of it, and once or twice genuinely amused. My suspicion is that this was shot more or less sequentially, as once through that dreadful opening sequence everyone seems to relax into their role—with the wholly unexpected result that not only is no-one completely terrible, but a couple of decent performances emerge: Jonathan Sayres as all-purpose red-herring, Hank (he has a knife, a chainsaw, a hockey mask…); Stephanie Northrup as group bitch / unexpected Final Girl, Parker; and Gloria Balding as Shay the virgin (“…and I am so goddam horny!”). No-one here is remotely of school age, of course (“Were you, like, left back?”), which makes the micro-miniskirts and push-up bras and self-declared expensive lacy underwear at least a little less tacky. I should probably mention, though, that despite all this, the leering camerawork, the non-stop sex-talk and the couple of attempts at sexual activity (both bloodily interrupted), there’s no actual nudity. Sorry.

(If you have any thought of watching this, avoid the film’s trailer: it not only shows most of the kills, but gives away the killer’s identity, rendering the entire exercise more pointless than it inherently is.)

Hidden (2005)

A group of young adults runs through the bush, participating in an elaborate game of hide-and-seek that grows increasingly intense—and potentially deadly. As they conceal themselves from their pursuer, Carl (Luke Alexander), briefly forming partnerships or, conversely, betraying one another, several of the participants find themselves afflicted by memories and visions. Mark (Kiel McNaughton) becomes convinced that he is possessed by a taniwha, and begins hunting the others in earnest; Imogen (Sarah Jane Wright) begins to recall incidents from her difficult childhood; Kate (Liesha Ward-Knox) and Chris (Gavin Rutherford) both admit to the sceptical Jacqui (Kerry Warkia) and Jason (Blue Pilkington) that they believe they have seen the ghost of a little girl notoriously murdered in the area some years before… Writer-director Tim McLachlan’s Hidden is a film I really wish I could like more than I do. As a piece of low-budget, guerilla film-making, a production brought to fruition purely through the dogged perseverance of a handful of believers, it is admirable; as a completed project, it is frustratingly insubstantial. The film’s credits carry what I consider a significant reference to the Unitec Institute of Technology’s School of Performing & Screen Arts: Hidden feels exactly like a film-school project, a string of vignettes in which everyone gets a scene or two, but no one plot is allowed to take centre-stage to the point of being what the film is “about”. Similarly, there are too many characters to come to grips with; it is too easy for the viewer to miss story details while simply trying to sort out who is who. The final frustration is the film’s climax, which consists of a revelation rather than a resolution—that is, it doesn’t really explain what we’ve been watching. However, any criticism of the ending as over-obvious should be tempered by the reality of Hidden‘s production history—with most of the film shot in 2001, but production not completed until 2005, by which time its ending had, so to speak, been done to death. But whatever its shortcomings as a whole, Hidden does have some piecemeal virtues. Its young cast tries hard and, clearly, went through the wringer physically during production; while the film makes excellent and often spooky use of various bushland locations outside Auckland.

The Nun (2005)

Original title: La Monja. Mary (Lola Marceli) wakes from a disturbing dream about her time at a Spanish boarding-school, where she and her friends were in conflict with a nun called Sister Ursula (Cristina Piaget), to find her house awash. As she struggles to stop the taps and drain the sinks, the spectral figure of a nun emerges from the water and slashes her throat… Mary’s teenage daughter, Eve (Anita Briehm), arrives in time to catch a glimpse of her mother’s killer, but no-one believes her; her friend, Julia (Belén Blanco), confides to police that Mary had once before tried to kill herself. At the funeral, Eve is approached by Cristy (Teté Delgado), an old schoolfriend of her mother’s, who mentions that another of the group of friends recently died in London under mysterious circumstances. Cristy persuades Eve to meet her the following day, at her hotel, so that they can talk, but when Eve arrives it is to find Cristy bloodily dead in the elevator. Convinced that the truth behind the deaths lies in Spain, Eve joins Julia and her boyfriend, Joel (Alistair Freeland), on their planned trip to Barcelona. With the help of seminary student, Gabriel (Manu Fullola), Eve learns that the boarding-school attended by the friends was closed down after the mysterious disappearance of Sister Ursula… Written by Jaume Balagueró and directed by former editor, Luis de la Madrid, The Nun is a confusing and overlong entry in the “deadly secret from the past” subgenre. Two of the banes of my film-watching life rear their ugly heads again: (i) everything is too dark; and (ii), as with Darkness, also a Spanish-American co-production, too much important dialogue is delivered in heavily accented English, so that (as is also a consequence of the perpetual darkness) it is easy to miss important details. This is particularly true with respect to the various gruesome ways in which the now-adult schoolfriends are being killed off, which is the film’s best idea. The division of the victims and the detectives is also interesting, with the women being picked off by Sister Ursula now in their thirties, while the younger generation takes on the grim task of discovering the truth and laying the deadly ghost. Overall, however, the screenplay of The Nun is the basis of the film’s failure, being full of improbable but plot-necessary touches like the five friends all having the names of saints, and providing absurdly arbitrary “answers” to the very questions it raises. (Why is Sister Ursula taking her vengeance now, after eighteen years? – because they drained the pond. If she travels via water, why couldn’t she get out of the pond before? – because there was holy water in it. Eh?) The “twist” ending, meanwhile, not only comes out of the blue, but doesn’t make sense in what I will call geographical terms. We might also fairly object to it being Joel, previously the group idiot – and who gets to speak the all-too-accurate line, “What is this, I know what you did eighteen summers ago?” – who is responsible for making the sweeping deductions by which the “truth” is finally revealed. The Nun does stage some impressively gruesome kill-scenes, but the preceding water-business tends to drag. It is never scary, though; and the waterlogged nun is actually pretty silly. The film was produced by Brian Yuzna, who gives himself a jokey cameo of sorts: one of his screen credits appears in Eve’s in-flight movie. There is also a misplaced bit of comedy when Eve sees, not a gremlin, but a nun on the wing of her plane…

Bloody Mary (2006)

One of a group of psychiatric nurses is forced by the others to take off her clothes, descend into the tunnels beneath the hospital where they work and, while standing in front of a broken mirror, intone, “I believe in Bloody Mary.” Jenna (Danni Hamilton, aka Danni Ravden), the leader of the group, tells the others that she has arranged an extra scare for Nicole (Jessica Lous, aka Jessica Valentine) by having her boyfriend, Scooter (Christian Schrapff), already hidden in the tunnels; so they are not at first worried when Nicole begins screaming in terror—until Scooter shows up behind them, apologising for being late… With her sister Nicole reported missing, crime-writer Natalie (Kim Taylor) returns to town to help with the search. After a public meeting, Natalie is approached by Nicole’s ex-boyfriend, Paul (Cory Monteith), who tells her hurriedly that her sister had been “playing the mirror game”. From Nicole’s friends, Natalie gets expressions of sympathy but no help; Jenna gives her a small mirror pendant, which she says is Nicole’s. Outside, Jenna comments darkly that they have to take care of Paul. When a frightened April (Lindsay Marett) insists that they have to get rid of the mirror before someone else finds it, Jenna is initially furious, but then abruptly concedes that she is right. That night, the two make their way towards the trapdoor that opens into the tunnels—only for Jenna to knock April out, throw her down into the tunnel, and lock her in… Having only a vague knowledge of the urban legend of “Bloody Mary”, I was at a disadvantage from the outset with this low-budget effort written and directed by Richard Valentine—but having watched the whole thing, I’m inclined to think a better understanding of the back-story would have made it more rather than less confusing. “Confusing” is the operative word here: Bloody Mary is one of those aggravating films that spends much time dwelling on unimportant details (like whether Paul dumped Nicole or the other way around), but never bothers to explain why any of the characters are doing what they do—culminating in something that is not so much a plot hole as a black hole: never at any point do we find out what Jenna and her fellow believers expect to gain from providing Mary with victims! But this is only the central stupidity in a network of stupidity as vast as the network of tunnels running beneath the world’s most poorly run psychiatric hospital—which comes equipped not only with a helpful trapdoor entrance, but even more helpful blueish lighting, presumably so that we don’t miss anything to do with the “strip naked first” aspect of the invocation of Mary. In fact—we know very well what to think of Bloody Mary from the moment Nicole is forced to strip during the film’s the opening sequence…but there are plenty of other bits of gratuitous nudity here (including a butt-shot of Cory Monteith). The acting in this film is universally poor, and the screenplay is full of senseless bits of dialogue and jarringly improbable behaviours, which at least provoke the occasional laugh. (I particularly enjoyed Natalie’s ex-boyfriend choosing the meeting held to arrange a search for the missing Nicole as an appropriate forum in which to hit on her.) Bloody Mary‘s gore scenes are plentiful, though, if not particularly explicit—which I appreciated, even if others may not, since Mary is an eyeball-collector…

Dark Ride (2006)

Asbury Park NJ, 1989. On the last afternoon of the carnival season, teenage twin sisters enter the sideshow’s “dark ride”—and never come out. The subsequent investigation uncovers a series of gruesome murders: the ride is closed down, and the killer committed to a mental hospital. Fifteen years later, after slaughtering his attendants, he escapes… Trying to save money, college students Cathy (Jamie-Lynn Sigler) and Liz (Jennifer Tisdale) join a road-trip to Spring Break planned by Steve (David Rogers), his geeky roommate, Bill (Patrick Renna), and their friend, Jim (Alex Solowitz)—even though Cathy and Steve are on the verge of breaking up due to the latter’s infidelity, and Liz once had an awkward hook-up with Jim. As they drive through New Jersey, the group stops at a gas-station, where Bill finds a flyer announcing the reopening in three days’ time of the carnival’s dark ride. Over Cathy’s protests, the others agree to break in and spend the night in the attraction. On their way to the pier, they pick up a hitchhiker, Jen (Andrea Bogart), who supplies the group with marijuana and happily falls in with their plans. Though Cathy refuses to leave the van, the others find a way into the ride—where they soon discover that they are not alone… You could forgive Dark Ride for its painfully derivative scenario if it did anything with its thievings; but instead it offers only a numbingly tedious rehash of films that, honestly, it feels like director Craig Singer and screenwriter Robert Dean Klein never actually saw for themselves, but just read about somewhere. This thing is a compendium of clichés populated by two-dimensional morons without a single redeeming feature between them—and that’s before they start smoking pot. We’re then forced to endure their company and the drivel that comes out of their mouths for a full hour before the killing starts; as well as an oral sex scene that goes on longer than the real thing. Apparently set up as Final Girl, Cathy turns out to be even more of an idiot than the rest; while the inevitable “twist” ending is obvious from the moment we are offered the “urban legend” of the ride’s back-story. The “dark ride” itself is never the effective setting it could, and should, have been, chiefly because it never convinces as a ride: it’s obviously just a set, far bigger than it should be, whose various areas and scare-tricks bear no relation to one another—and which has no tracks. Some of the gore-scenes in Dark Ride are effective (I particularly admire the killer’s ability to decapitate someone without getting blood in his victim’s hair), but they don’t make up for the rest. This is a thoroughly unpleasant film, and not in the least in a good way.

(Dark Ride also pulls a trick I’m getting very tired of, the “back-story via newspaper headlines behind the credits” thing. This did give me my only laugh, though: I’m pretty sure that if “14 more bodies” were found, you wouldn’t need “a vote” to close the ride down.)

The Tall Man (2012)

The small town of Cold Rock, Washington, is left economically devastated after the closure of the mine that was its main employer. Poverty is endemic; even the local school has closed. But the town suffers another kind of devastation when its children begin to disappear. Though it is assumed by most that the town has a killer in its midst, there are also whispers about a local legend known as “the Tall Man”; some even claim to have seen him… After losing her husband, who was the town doctor, nurse Julia Denning (Jessica Biel) tries to provide care for the townspeople, but faces resistance and even resentment. Julia takes a particular interest in local teen Jenny (Jodelle Ferland), who suffers from hysterical dumbness due to her home circumstances—which include her sister having recently borne the baby of her mother’s boyfriend. At night, Julia is glad to retreat to her isolated house on the edge of town, which she shares with her young son, David (Jakob Davies), and her live-in nanny, Christine (Eve Harlow). One night, however, Julia wakes to discover Christine bound and bloodied in the kitchen. She is in time to catch a glimpse of David being carried away by a tall, long-coated figure—and launches into a desperate chase to get him back… The Tall Man is a difficult film to review, as it depends upon its plot-twists for its effect, and it is impossible to discuss it properly without giving those twists away. It can be said, however, that this is a film which, from the beginning, has probably been playing to the wrong audience. Its evident connection to the “Slenderman” stories and the fact that this was Pascal Laugier’s follow-up to the brutal Martyrs understandably leads viewers to expect a horror movie, but this is, rather, a psychological thriller with sociological underpinnings. These misdirected expectations and the film’s structure make it difficult to take in all that The Tall Man is saying on a single viewing—some of which is more than a little outrageous. To be fair, the issues that the film raises about the effects of poverty and neglect, and the responsibilities of government, are perfectly legitimate; but its handling of those issues needed to be far more detached and balanced. As it is, the film stacks the deck by restricting its point of view to one side of its argument—something reflected, in practical terms, by the fact that it includes only one emotionally shattered parent amongst its cast of characters, despite the number of children we know have gone missing. The most overt giveaway, however, is The Big Speech that Laugier eventually puts into the mouth of Julia Denning (a mistake both thematically and dramatically, as Big Speeches usually are: show, don’t tell, Pascal!). A studiously deglamourised Jessica Biel was one of The Tall Man‘s executive producers, and it is easy enough to see what drew her to the project: not only does she dominate the action but, by the end, has effectively played three different characters. She is supported by Stephen McHattie as the detective investigating the disappearances, William B. Davis as the local sheriff, Colleen Wheeler as the bereft Mrs Johnson, and Samantha Ferris as Jenny’s mother. Filmed (of course) in British Columbia, The Tall Man‘s art direction succeeds in creating the necessary atmosphere of deprivation and depression about the town of Cold Rock, but we needed to see more of those conditions from the perspective of the townspeople, not merely from that of a relatively privileged outsider.

The Hazing Secret (2014)

Megan Harris (Shenae Grimes-Beech) wakes from a graphic dream in which she is involved in the death of another girl during a hazing ritual to discover that she is suffering from an amnesiac condition in which, each day, her new memories are wiped by sleep. She learns this and other things about herself from a video log, which she records each night for her own use the following day. Megan is shocked to realise that she has amnesia for five years, as the result of an accident. The newest log informs Megan that she has an appointment with her psychiatrist, Trent Rothman (Keegan Allen), who has been working with her since he was a grad student. On her way to Rothman’s office, Megan encounters Kim (Kaitlyn Leeb), her friend and sorority sister, who tells her that Everton College will be holding its five-year ‘Greek’ reunion and urges her to attend. From Rothman, Megan receives both good news and bad news: she was not involved in the death of Melissa (Sidney Leeder), which was due to alcohol abuse; but her own “accident” was actually a suicide attempt, in which she jumped from the roof of the sorority. Like Kim, Rothman urges Megan to attend the reunion, arguing that this might result in a memory breakthrough. She does so—and finds herself fighting to remember the truth of the past in time to save her own life… It seems as if I’m calling one film or another “the stupidest thing I’ve seen in ages” in pretty much every Et Al. update these days—but it’s honestly more about the kind of films I’m watching than any lack of vocabulary. The Hazing Secret continues this, uh, proud tradition via a screenplay that manages to blend I Know What You Did Last Summer with 50 First Dates: I’m only sorry I wasn’t a fly on the wall at the pitch-meeting. From the opening-scene hazing in a sorority basement permanently tricked out with rows of lit candles and a polished black coffin to the world’s least surprising “twist” ending, this one’s a doozy. The acting is terrible; the writing is worse; our four central sorority sisters are so paint-by-numbers, it’s hilarious, with outsider Megan and nice-girl Kim joined by Queen Bitch Nancy (Amanda Thomson) and her weak-willed 2iC, Gwen (Megan Hutchings); while you won’t believe what this film dares serve up as a police detective and a psychiatrist! The former is Melissa’s brother and Megan’s ex-boyfriend, Brian (Brett Dier), who dropped out of law school to “become a cop” (just like that), and apparently has absolutely nothing else to do with his time but pursue the truth about Melissa’s death—more in the interests of revenge than justice, it seems. “Doctor” Trent Rothman, meanwhile, is so utterly skeevy that we can only blink in astonishment at the film’s evident conviction we’ll be shocked by the revelation that he has an agenda besides treating Megan. No sooner have the four sorority sisters been reunited than they begin receiving mysterious threats relating to Melissa’s death; and before much longer there have been two attempts made upon the lives of the four—one of them successful. As Megan struggles to put the pieces of her past together before the killer can strike again, she must deal with a terrible discovery: that Melissa’s death was due to the hazing; that she, Megan, was involved; and that her subsequent suicide attempt was made out of guilt…

Deep Blue Sea 2 (2018)

I’m not actually going to review this here; not even a short review. I simply want to record my giddy delight at realising that this thing may be even more moronic than the first one…

“Cherry Mount”, “Miss Beaver” – they really weren’t trying to be subtle, were they?

You realise I’m now going to have to seek out a copy of Deep Blue Sea 2…

LikeLike

Not exactly. Imagine my horror when I (briefly) thought it was a serious film??

Yes. Yes, I do. 😀

LikeLike

Reviewed both DBS and DBS2, and I agree with your summary.

https://blog.firedrake.org/archive/2019/05/Deep_Blue_Sea.html

https://blog.firedrake.org/archive/2019/05/Deep_Blue_Sea_2.html

LikeLike

OMG you hadn’t seen the first one before!!??

Anyway, I hope you’re suitably grateful for the motivation to watch both. 😀

LikeLike

That’s why I read the B-Masters… I mean, I heard about Plan 9 after one of its many “rediscoveries”, probably in the 1990s, but I didn’t really get into enjoying bad film until I met you lot.

Shark in Venice is still very high on my list of “how did anyone involved think they were making something worthwhile” films, though.

LikeLike

Haverlyite – the first McGuffin. How do you pronounce it?

LikeLike

Hav-er-lee-ite?

LikeLike

It’s a silent serial, so the issue never really came up! – but yeah, that’s as good a guess as any.

(And trust me, there were loads of McGuffins before that!)

LikeLike

Oddly enough, I was just reading the Wikipedia entry for The Invisible Host a few days ago. Someone shared a cover image on a Facebook group I belong to, so, never having heard of it before, I looked it up.

LikeLike

It was published by the Mystery League, known for their brilliant cover art concealing (generally) mediocre-to-bad books. I’m reading through them with a friend and found it that way.

LikeLike

The emphasis on motorized policing in “Officer 444” reminds me that the magic of two-way radio was a big enough development for there to be both a 1932 feature film and a 1937 serial, both titled “Radio Patrol” inspired by the then-new equipment. The feature was more of a character piece, while the serial was based on a comic strip and featured the usual adventurous situations seen in such entertainments. As for The Frog’s “subtle aides,” I imagine anyone who wears such an outlandish and eye-catching disguise needs *somebody* on his team to be subtle.

Would you recommend that I watch “The Frightened Lady,” “The Case of the Frightened Lady,” “The Case of the Frightened Lady,” The Frightened Lady,” or “Criminal at Large”?

Cameron Mitchell as Caesar. Seems odd. Mitchell was a talented actor, not used well in most of his films, (especially after 1980, but he had to eat, too), but Caesar?

“Hidden” is on YouTube in its entirety, for anyone who cares to look.

“Bloody Mary” — these are actual nurses? Not high-school students at some career training, or even nursing students? (The latter because I knew a couple of nursing students, in my youth, who were pretty darned wild.) Women sufficiently trained to be psychiatric nurses are feeding a monster by making a coworker strip, go into tunnels, and play “Bloody Mary.” And a psychiatric nurse goes through this hazing, rather than report all of the hazers to management. Holy gee whiz.

“The Tall Man” — a single parent nurse, in a small town that appears to be dying, can afford a live-in nanny?

Sorry to go on so long, but this installment of Et Al. has me more puzzled than usual.

LikeLike

Would you recommend that I watch “The Frightened Lady,” “The Case of the Frightened Lady,” “The Case of the Frightened Lady,” The Frightened Lady,” or “Criminal at Large”?

No. 🙂

When I’ve seen more than one of them, I’ll advise.

The film’s not really *about* Caesar, which makes it even odder.

Actual nurses, yes. Just one of the many gobsmacking things about the film.

A single parent left in comfortable circumstances by her husband. (They were *in* the town, but not *of* the town.) And it’s not so much a nanny as a roommate / helper.

LikeLike

I confess that I enjoyed both Evil Under the Sun and Death on the Nile, despite how campy they both were.

I have vague memories of watching The Shooting Party on cable TV when I was in High School. Maybe I’ll look it up again.

Agreed about The Tall Man. I ultimately thought it wasn’t a bad movie, but it definitely wasn’t what I was expecting.

LikeLike

Death On The Nile, while not camp-free, is on the acceptable side of the line. The Mirror Crack’d was where things began to tip.

Yes, it’s one of those films you almost have to watch twice because your head is almost unavoidably in the wrong place the first time.

LikeLike

So, would you recommend watching Tomie: Replay? I saw the original in the wake of Ring bringing Asian horror cinema to the forefront of America’s consciousness, and found myself so flabbergasted that I ended up shrugging and moving on to other things rather than watch the second one. However, if it manages to be more coherent than the original, I may have to give it a go.

LikeLike

More coherent, yes; coherent, no. 😀

If Ringu was your only exposure to J-horror I can imagine that you found Tomie rather brain-melting. You’d probably get along better with them these days. (Hmm… You’re making me want to bump the next in my rental queue.)

LikeLike

Thinking back, I believe Tomie was the first thing I grabbed at the rental store after seeing Ring. (Not that there was much selection for such films then.) It might well be worth rewatching Tomie just to see if, after all these years of Asian horror films, I’m better able to break it down; and then give the second a try. I do remember the trailer for Replay grabbing my attention when I first saw it…until the name came up.

LikeLike

I think you’d certainly do better now, though it’s not like you’re going to discover on a second viewing that it makes sense. 🙂

Kanno Miho is a superior Tomie, though, so it has that going for it.

LikeLike