“I shall show you strange things about the mind of man…”

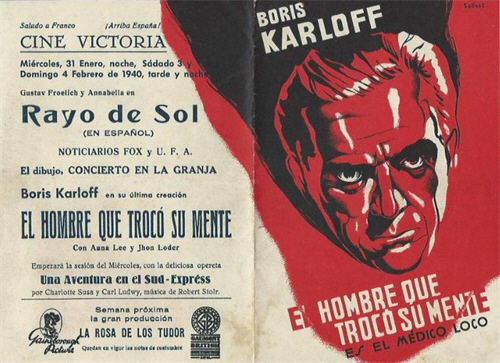

[aka The Man Who Lived Again aka The Brainsnatcher aka Body Switch aka Dr Maniac]

Director: Robert Stevenson

Starring: Boris Karloff, Anna Lee, John Loder, Frank Cellier, Donald Calthrop, Cecil Parker, Lynn Harding

Screenplay: L. du Garde Peach, John L. Balderston and Sidney Gilliat

Synopsis: To the dismay of her colleagues, Dr Clare Wyatt (Anna Lee) resigns her position as a surgeon in a London hospital to take up a research post, working with the brain expert, Dr Laurience (Boris Karloff). Dr Gratton (Cecil Parker) warns her that Laurience is no longer the man she trained under, but has since acquired a strange reputation. Clare is adamant, however, and remains so in face of pleading from reporter Dick Haslewood (John Loder), who wants her to marry him. Dick too has learned some odd things about Laurience, including his claim that he is, “Discovering the human soul.” Clare is unperturbed, and sets out for the isolated country house in which Laurience has set up his laboratory. She is perturbed, however, when she arrives at the nearest station to find Dick there before her: he tells her that he has persuaded his editor there is a story in Laurience. Clare shakes him off and takes a horse-drawn cab to Laurience’s house—only for the reluctant cabbie to drop her some distance away. She is admitted to the house by an abrasive individual in a wheelchair called Clayton (Donald Calthrop), who brusquely directs her to the laboratory. Clare is delighted to be reunited with her mentor, but dismayed to find him so changed. Laurience speaks bitterly of his past reputation as a leading surgeon and an authority on the brain—and of his rejection by the European scientific community, which considered his ideas too outrageous. He tells Clare that he wants her as his assistant, in spite of her lack of research experience, because of the enthusiasm and courage she displayed as his student. Clare promises Laurience that she will follow him without fear… That night, after Clare has gone to bed, she is startled by the sound of stones hitting her window—but not surprised to find Dick down below. He climbs up the ivied trellis, telling Clare what he has learned: that Laurience has a sinister reputation in the village, and that no servant will stay in the house. He tells Clare that he will be staying at the village inn, and she agrees to send for him if anything goes wrong. The following morning Clare receives further discouragement from Clayton, who jeers at her contention that she understands Laurience. Meanwhile, Dick has filed an inflammatory story about the scientist. When he learns that Laurience will not see this deliberate provocation, as he does not take the paper, Dick makes a point of carrying a copy up to the house. A horrified Clare intercepts it, but Clayton shows the article to Laurience; indignantly denying that he had anything to do with it. Back in London, Lord Haslewood (Frank Cellier), the owner of the paper – and Dick’s father – criticises his editors for not making the story more prominent. Not only does Lord Haslewood believe that science is news, he has founded a research institute to ensure that any new developments will be his property, and reported first in his papers. He decides to meet and talk with Laurience himself. Meanwhile, Laurience reveals to Clare the nature of his research. He argues that the only difference between a living brain and a dead one is that the latter has had its thought-content removed; and that, in his belief, it is possible not only to extract and store that content, but to transfer thoughts – in effect, a personality – from one brain to another…

Comments: After establishing himself in Frankenstein in 1931, Boris Karloff cemented his reputation as a horror star across 1932 via a trio of films – and effectively four roles – that allowed him to display his range: as the sinister mute butler, Morgan, in James Whale’s The Old Dark House; the title character in The Mask Of Fu Manchu; and as both the bandaged-swathed monster and his seemingly human incarnation in The Mummy.

Having reached this pinnacle so swiftly, after so many years of struggle, Karloff then showed unusual shrewdness in his subsequent management of his career—at least during the horror boom of the 1930s. While always staying loyal to Universal, and returning to the studio at regular intervals, Karloff negotiated contracts that allowed him to remain independent and to pick and choose his roles—and to move as he liked between Hollywood and Britain.

However, in the mid-30s, the boom began to wane—not least because of the British censorial crackdown on screen horror, which dissuaded the American studios from continuing to invest heavily in the genre. From 1936 onwards, two things happened simultaneously: there was a shift from horror to science fiction; and budgets began to shrink. Together, these forces produced a rush of low-budget “mad scientist” dramas—an astonishing proportion of which starred Boris Karloff. It is likely that, failing to predict his own ongoing bankability – let alone that he would still be working regularly some three decades later – Karloff was determined to take financial advantage of what he may have viewed as his last significant professional opportunity.

Karloff is the best thing about the majority of these films; but if none of them are great, most of them are interesting—particularly in their recurrent use of their star, whose characters are usually not outright “mad” so much as over-reachers, whose good intentions invariably lead them down the traditional road.

Most of these science-fiction quickies were churned out in America; but 1936 found Boris back in Britain making one of the most entertaining of the entire clutch—one in which he is (in movie terms) quite indisputably mad…

With only just over an hour at its disposal, The Man Who Changed His Mind has no time to waste; and it introduces us immediately to one of its most important aspects, its female lead.

It is interesting to debate how we are supposed to take Dr Clare Wyatt. Though she is set up as this era’s anathema, a “strong-minded woman” (she’s even called that!), and though her collaboration with Dr Laurience ends in tears, so that you can if you choose read this as yet another parable of the inevitable consequences of women stepping out of their “proper” sphere, it doesn’t seem to me that there’s any real sense of condemnation in the way the film handles her. On the contrary, first and last – literally first and last – it shows her in control in a demanding situation, and finally pulling off the kind of rescue usually reserved for “the hero”.

There’s no doubt, though, that The Man Who Changed His Mind intends to surprise the viewer, when one of the gowned and masked surgeons seen leaving an operating-theatre is revealed as a woman. Clare’s older colleague, Dr Gratton, bemoans her decision to leave surgery for research, and also warns her that Dr Laurience – pronounced “Lorenz” – is not the same man she knew when she was training under him: that they “threw him out” of Genoa, for his “impossible ideas”.

Gratton and another doctor condemn Laurience as “mad”, “unorthodox” and “queer”; Clare counters with “eccentric”, “brilliant” and “genius”.

Clare’s packing is interrupted by Dick Haslewood, who has also come to warn her against Laurience; although he is motivated by self-interest, in that he wants Clare to marry him.

This cliché situation is handled quite lightly, though, in spite of the standard entitled harassment that insists that, no matter how much time and effort a woman has put into getting qualified and establishing herself professionally, she should just chuck it all away the moment a man looks at her; and again, there’s no overt sign we’re supposed to side with Dick: his response to her insistence that firstly, she must do her job, and secondly, that’s she’s used to looking after herself – you guessed it: “How I hate strong-minded women!” – is treated basically as a joke.

Dick wasn’t kidding, though, when he threatened to follow Clare to Laurience’s house: she finds him at the nearest station when she arrives, having caught an earlier train; though his official excuse is that he has been commissioned to interview Laurience. Clare manages to leave him behind, and is driven to the house in the small village’s one horse-drawn cab; or at least, almost to the house: she gets the Borgo Pass treatment from the cabbie, who informs her tartly that, “I don’t go to that door.”

Clare’s reception at the house itself is no more encouraging: she is admitted by a man in a wheelchair called Clayton, who introduces himself as, “One of the doctor’s more hopeless cases.” As Clare runs an instinctive professional eye over him, Clayton points to his head and announces, “Intercranial cyst”, adding that, yes, he should be dead—and that in fact, most of him is. He directs her brusquely to the laboratory.

We must be careful how we interpret the character of Clayton, who is the source of most of the film’s overt humour via an almost-constant stream of sarcastic misanthropy—but who isn’t just here to be funny. These early, mouthy scenes establish his idiosyncratic and abrasive personality.

Likewise, we must refrain from flinching every time we cut to Laurience and find him smoking in his laboratory…

{*shudder*}

On the other hand, Laurience’s private laboratory is another of the film’s small pleasures, an amusing mix of the usual retorts and bubbling flasks with some less explicable electronic hardware. These gadgets and glassware are almost enough to keep us from noticing that the film offers not the slightest hint as how Laurience actually achieves his goals; almost.

Clare and her former mentor share a warm greeting, but almost immediately Clare reacts with dismay to how much Laurience has changed since she last saw him, how much he has aged.

As I say—this isn’t a film with much time to waste, and instead of avoiding the issue at all, Laurience instantly launches into bitter speech:

Laurience: “I am changed! The leading surgeon in Genoa; the greatest authority on the human brain—until I told them something about their own brains! Then they said I was mad!”

You guessed it, folks: The Man Who Changed His Mind is a prove-the-fools-wrong film; and we all know how well that usually works out, right?

Clare questions Laurience over her own position, pointing out self-deprecatingly that he could have hired a far more experienced scientist than herself as his assistant. Laurience replies passionately that he didn’t want experience, someone whose “mind is set”: he wanted the courage and the faith in the work that he remembered from Clare’s days as a young student. Laurience then warns Clare that he shall show her some strange things, but adds that she must follow him without fear. Fired by his enthusiasm, she promises to do so.

After Clare has gone to bed, Laurience confronts Clayton, who admits bluntly that he doesn’t like women, and doesn’t want her in the house:

Laurience: “But she’s a scientist!”

Clayton: “A female scientist!? All tears and hysterics and can’t keep a secret!”

Laurience insists that Clare wants to work with him, and that she is going to—admitting, however, that he has not yet fully explained the nature of that work to her. Clayton urges him to do so, adding satirically, “Perhaps she will change her mind!”

Meanwhile, Clare is perched on her own windowsill having a conversation with Dick, who tells her what he has learned in the village about Laurience and his household. He responds inadvertently to Clare’s insistence that he go away, plunging to the ground when the trellis collapses under him, and hiding in the bushes went a suspicious Laurience appears at the front door and shines a torch around. Clare is amused by this, but startled when Laurience comes knocking at her door, asking about voices. However, he accepts her hurried denial.

Clare earns another dose of sarcasm from Clayton the next morning when she sets about washing up—not the dishes: given the accumulation, that’s a task beyond any woman—but the coffee-pot. He continues to nag at her, accusing her of disliking him as much as he dislikes her, and jeers at her assertion that she understands Laurience.

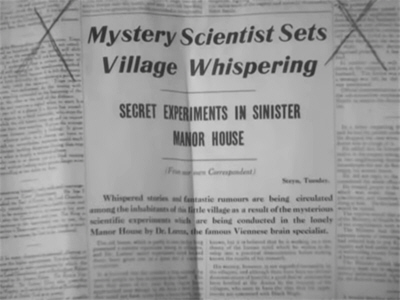

Up at the village inn, Dick is admiring the morning edition of the Daily Gazette, which carries his own inflammatory story on Laurience. Learning that they don’t take the paper up at “the manor”, Dick makes a point of delivering a copy. Clare is pleased to see him, but horrified at his handiwork, which she conceals from Laurience. (We note that Dick spells it “Lorenz”: did they, ahem, change their minds, or does this reflect Dick’s lack of professionalism?) Clayton makes a point of bringing it to his notice, however, only to be accused of being the source. Laurience reminds Clayton angrily that only he is keeping him alive; and if he were to miss one injection…

Clayton: “I don’t mind dying; but to be accused of journalism…!”

This remark properly introduces the main subplot of The Man Who Changed His Mind, in which the press – and perhaps more correctly, press barons – take a beating. Alas! – would we could say that much has changed in this respect since 1936.

The film has a great deal of satirical fun with the character of Lord Haslewood, who makes his editors’ lives miserable via his, ahem, strictly hands-off management style:

Editor #1: “If you say so…”

Haslewood: “I don’t say so: it’s a fact!”

Editor #2: “But I have other views—”

Haslewood: “There are no other views!”

Editor #2: “Then what do you want us to do?”

Haslewood: “Nothing! Not a thing. You know I never interfere in the conduct of my papers…”

The point of contention this time is Laurience—and not just because it is Dick who has filed a story on him. Dick himself, by the way, is also made the object of the film’s satire: his story is a complete fake, a beat-up constructed out of village gossip but posing as an interview with Laurience: something that will later come back to bite him (although not as hard as it should, presumably out of deference to his position of putative romantic lead).

The ensuing argument with his editors reveals that Haslewood has founded a scientific research institute out of his belief that “science”, these days, is news – “If properly handled, front-page news!” In this way, the Haslewood papers get full benefit of anything produced by the Haslewood Institute—

—a situation which rather delightfully illustrates one of the most cherished, and tenacious, beliefs of the science-fiction film: that SCIENCE!! is something that happens by way of sudden DISCOVERY!!, rather than via years of painstaking, step-by-step progress.

The upshot of Lord Haslewood’s argument with his editors is his decision to see Laurience for himself, and recruit him for his Institute.

Meanwhile, Laurience is easing Clare into the nature of his research, explaining to her his theory that the only difference between a live brain and a dead brain is that the latter has been “wiped”, the thought-content, the personality, the mind removed. He goes on to assert his belief that there may be a way of actively extracting the thought-content from a living brain, and to store it – “As you would store electricity” – leaving the brain itself alive but empty.

Moreover, Laurience is in a position to prove his theory. He introduces an experimental chimp, a gentle, friendly and affectionate animal, which has been trained to sit on one side of what looks worryingly like a two-for-one electric chair, and to don a helmet sporting a range of electrodes, from which wires run to one of Laurience’s electronic doo-hickeys.

“You see, he likes it. To him it’s just like falling asleep,” comments Laurience (a line I have no doubt was included to placate the British censors, who were always touchy about the treatment of animals in films, and rightly so).

Laurience then sets his doo-hickey in motion: its moving parts go up and down, electronic whining fills the air, and a Van der Graaff generator springs to life. The end-point of the process is, we gather, a kind of storage container, which begins to glow as Laurience works his equipment.

SCIENCE!!

To Laurience’s contention that the mind of the chimp has been drained, and is now in storage, Clare demands to know how he can prove it: the chimp, unconscious in its seat, might simply be asleep or anaesthetised. When she agrees that placing the chimp’s drained mind into a second animal would prove it, Laurience tells her that for the first time, he intends to make the attempt. He introduces a second chimp, this one aggressive and dangerous.

(Since the plot requires this animal to resist, and to be forced into its seat, most of this takes place off-camera, with chimp-shrieks dubbed in.)

Laurience goes through the same process with the second chimp, draining its mind into a second storage battery. He then attempts to place the mind of the first chimp into the brain of the second one—effectively by – say it with me, now! – reversing the polarity.

Once done, Laurience releases the second chimp, which is now conscious. It immediately displays a completely different temperament—and that it knows which pocket Laurience keeps his chimp-treats in. The scientist then releases the first chimp—which shrieks and snarls.

An excited Laurience insists that this proves his theory: that the mind of each animal has been transferred into the other—its personality, its likes and dislikes—what, if they were human beings, would be called “the soul”…

Clare’s protest is immediate and vehement, prompting Laurience to agree that she is right, of course: he can’t do that…

Dick is on the verge of departing the village inn when his father arrives. He is gratified to win praise from Lord Haslewood for his work, but dismayed when his father asks for an introduction to Laurience. He resorts to some fast talking, insisting that no introduction is necessary, that Laurience must know him as the founder of the prestigious Haslewood Institute.

Lord Haslewood swallows this and sets off for the manor, where Laurience receives him with hostility as a representative of the press—pre-emptively rejecting any offer that Haslewood might make him with a frosty, “I am not for sale!”—

—although as it turns out, this isn’t strictly true; but we can hardly blame him, when Lord Haslewood offers him carte blanche in terms of facilities and resources for his work, in exchange for the Haslewood papers having exclusive rights to his discoveries—or rather, DISCOVERIES!! Even so, Laurience hesitates—insisting that he must have freedom to work in his own way. However, when Clare urges him to accept the offer, he capitulates.

And this, in its way – and despite its clinging to various other movie misconceptions – is one of the most interesting things about The Man Who Changed His Mind: it is that rare science-fiction film, certainly of this era, not only to present us with an actual research facility, but to make a plot-point out of the funding of research, and the consequences of that funding; as well as arguing for all the advantages of not working out of your own basement. (Not that it’s a literal basement in this case, but you know what I mean.) That said, of course it all goes horribly wrong for Laurience once he’s thrown in his lot with Lord Haslewood, so I’m not entirely sure what the takeaway message might be.

Haslewood then sets to work publicising his new venture—with the front page of the Gazette given over to Laurience’s new position at the Haslewood Institute. Every possible form of advertising is devoted to boastful references to “the brain genius”, from basic placards on walls to posters in trains to trailing signs in the sky. Dismissing his editors’ concerns about the crassness of his approach – he prefers the term “simplicity” – Lord Haslewood unveils his plan to make Laurience a household word:

Editor #1: “But no-one knows what he’s done!”

Editor #2: “No-one knows if he’s any good!”

Haslewood: “I flatter myself I know genius when I see it!”

And so certain is he, Haslewood arranges for a gathering of “the scientific community”, so that Laurience can explain his theories.

Dick is unimpressed by his glimpse of SCIENCE!! en masse, putting Clare on the professional defensive. She gets one of her most endearing moments here as, despite being both a doctor and a surgeon, she insists upon – to coin a phrase – calling herself a scientist:

Clare: “One of these days you’ll be proud to know me.”

Dick: “Wouldn’t you rather marry me instead?”

Clare: “Definitely not!”

Here The Man Who Changed His Mind delivers on yet another on the science-fiction film’s favourite conventions, the notion that scientists regularly get together for the express purpose of gasping and mocking and ultimately driving one of their number out of their midst: a form of public shaming which, we must note with some bemusement, this community persists with despite the fact that the invariable outcome is a loss of mental balance, a determination to prove the fools wrong and, more often than not, a body count…

(In reality the basic process happens, of course, but in a much quieter if no less effective way: they just don’t publish you.)

And having been driven out of Genoa for his “impossible ideas”, Laurience finds the English scientific community no less hide-bound and hostile, as he is literally hooted off the stage when he tries to expound upon his mind-swap theory. Led by the pompous Professor Holloway – a long-term critic of Lord Haslewood’s proceedings, we gather – the scientists walk out without giving Laurience even the barest chance to explain his experiments or how he drew his conclusions.

(The notion that a group of scientists, whatever they thought of an idea in general, wouldn’t want to stick around to hear how a radical experiment was conducted, is of course quite absurd.)

As his audience files past him, Laurience explodes in anger—giving the first overt indication of the direction in which he intends to take his research, as he speaks of transferring minds from “miserable, bent bodies” into bodies that are “young and strong”. He also sums up the departing in two words: “You fools!”

Mind you— Laurience might have a point when he talks about his colleagues’ “death-beds”: during the file-out, we note that Clare seems to be the only scientist in England who is (i) female, and (ii) under the age of fifty.

These days, however, the implications of Laurience’s experiments cause me even more manic glee than they did when I first saw this film, because I am now in a position to appreciate that what we have here is effectively a bloodless version of Dr Obrero’s brain-swap experiments from Zombi Holocaust—to which exactly the same objection may be made, i.e. for all the talk of “the common good””, it’s impossible to overlook the fact that, in each individual experiment, one person is doomed to get the fuzzy end of the lollipop.

(I suppose you could envisage a situation where the bodies of the brain-dead might be donated; but it’s hard not to further imagine the very rich getting first dibs, rather than the merely “deserving”…)

Clare hurries to Laurience, whom she finds in his laboratory setting up an experiment—which he intends to conduct on himself. She is horrified, insisting that, “Your mind is sacred”, and flatly refuses to assist him.

They are still arguing the point when Lord Haslewood bursts in—dissatisfied (to put it mildly) with the return on his investment. After Clare reluctantly leaves the men together, Haslewood berates Laurience furiously, calling him a “cheat” and a “charlatan”, and accusing him of, “Quackery that wouldn’t deceive a schoolboy.” He dismisses him from the Institute; adding a still-more devastating kicker when he points out to the scientist that he signed over his results in exchange for his new facilities; that the Haslewood Press still owns the rights to anything he might produce; and that, therefore, he cannot simply pack up and start again at the manor – or publish elsewhere – but on the contrary must cease and desist.

Wow. So not only is The Man Who Changed His Mind that rare film which treats research funding in a realistic manner, it follows through and becomes the first one ever to make a genuine plot-point out of intellectual property rights.

And it is that, by the way, rather than the scientific community’s rejection, which pushes Laurience over the edge. We get some fabulous montage and double-exposure work here, as the scientist goes into meltdown.

At length pulling himself together, Laurience apologises humbly to Lord Haslewood and admits all of his accusations—before asking him to stay just a moment more, to see just one thing…

Haslewood: “You must understand that once my mind is made up—”

Laurience: “You will not change it? Perhaps I can do it for you!”

And before he knows it, Lord Haslewood is strapped into Laurience’s new experimental chair…

Clayton is a sardonically amused witness of all this, and willingly agrees to be the other half of the experiment. Laurience pushes the wildly protesting Haslewood back into one of the two compartments of his new and improved mind-swapping equipment, lowers the updated metal helmet, and seals him in. He then sets his electronic doo-hickery into motion…

Laurience wakes up the new and improved “Lord Haslewood” first. After inspecting his new body, Clayton carefully lifts himself out of his chair—taking his first steps in many years. Meanwhile, Laurience retrieves “Clayton” from the second compartment. He, conversely, stares down in horror at his twisted body and its confining chair, and cries out involuntarily. This attracts “Lord Haslewood”, who reproves him, and asks that he treat his, Clayton’s, body with more care, as, “A temporary tenant.”

At this Laurience bursts out with his whole scheme: that Clayton should retain permanent possession of Lord Haslewood’s body, should become Lord Haslewood—and as such, go on funding his, Laurience’s, research. Clayton is amenable to the idea; even when Laurience points out that he doesn’t have to go on keeping “Clayton” alive. At this “Clayton” utters a desperate protest, accusing Laurience of murder. He calmly agrees that it is not just murder, but the perfect murder: “Death by natural causes!”

“Thanks for the sound body,” adds “Lord Haslewood”.

“Clayton” stares up at him, gives a burst of hysterical laughter—and dies.

This outcome suits both Laurience and “Lord Haslewood”—the former commenting darkly that since “mankind” has rejected him, he’ll use his work purely for his own purposes, the latter discovering the many pleasant aspects of being a wealthy baron—press and otherwise; along with a few annoyances like editorial meetings, at which his staff find him determined not merely to go supporting Laurience, but to increase his funding; although he agrees that toning down the publicity might be a good idea. On other matters he is unwontedly indecisive…

Given Laurience’s public downfall, Clare assumes that she’s out of a job. She calls at the Institute once last time, as she supposes, to collect her things. She is started to find Laurience there, still in his evening clothes; and even more so to learn he has convinced Lord Haslewood to give him a second chance.

But this is nothing compared to her feelings when Laurience’s speech about continuing his work rapidly morphs into a declaration of his desire to do it all for her (thus sort-of justifying the tacky selling of The Man Who Lived Again as the story of “a love-crazed scientist”).

He misinterprets Clare’s involuntary flinch away. “I understand: I’m old; but don’t you see? – with this new power, I needn’t stay old!” he argues; adding that she, too can eventually benefit; both of them transferring their minds into new bodies, as it becomes necessary: “Eternal youth!”

Clare moves to the window, her instinct to call for help. Laurience pulls her back—and understands when he sees Dick down below, pacing beside his car as he waits. While he is coming to terms with this unwelcome discovery, Clare slips away. Having watched the couple drive away, a scowling Laurience wanders over to his experimental equipment—his brow clearing as he contemplates one of the strapped chairs…

Clare, meanwhile, gives a not entirely accurate summation of her meeting with Laurience: “I told him I was going to marry you.” This is news to Dick as well as us: “You are?” he exclaims. “Yes, I think I am – now,” Clare adds, rather quelchingly.

That evening, Dick calls his father’s palatial home to announce his engagement. His arrival happens to coincide with Laurience trying to persuade Lord Haslewood – distracted as he is by his own entry in Who’s Who: “What a pompous ass I am!” – to summon him there.

There is an awkward moment upon Dick’s first entrance, since his father doesn’t know him from Adam. Dick, for his part, is surprised by his father’s unusual ebullience, also by his offer of a cigar; reminding him that he’s a non-smoker. Lord Haslewood then formally introduces him to Laurience, who tells Dick he knows all about him, “From my assistant.” This gives Dick the chance to break his news. Lord Haslewood rolls an inquiring eye towards Laurience, who responds cheerfully that he thinks he and Clare will make a splendid couple: “You look as though you haven’t had a day’s illness in your life!” he comments approvingly.

Left alone with his father, Dick – who has already raised his eyebrows at Lord Haslewood’s cigar – feels called upon to remonstrate when his father begins pouring out several fingers of whiskey. His remarks about the doctor convey nothing to Haslewood; but he is startled when Dick asks after his heart, and his medication. To his further dismay, he learns that even whiskey well-diluted with soda is off-limits to him.

Dick then departs, giving Lord Haslewood time to absorb the implications of this conversation…

Calling upon Clare, Dick cannot help expressing his surprise at his father’s positive attitude. Clare is at first amused, until Dick’s choice of words wipes the smile off her face:

Dick: “A change? Why, he was a different person!”

Clare stares at him in alarm as he recounts his warm reception from his usually distant father; her suspicions harden into certainty when she learns that Haslewood was showing a complete disregard of his doctor’s orders, and that he and Laurience seemed, “As thick as thieves.” She breaks her date with Dick, though without telling him why, and rushes off to the Institute.

Laurience at first evades her questions, but when pushed he offers a half-truth: that Clayton offered himself as an experimental subject, but the shock proved too much for him. Clare is entirely unpersuaded: she warns Laurience that, the next day, she intends to bring Dick and Lord Haslewood together and get to the bottom of things.

Laurience then returns to the Haslewood mansion, where he finds the lord of the manor in a very different mood from his earlier jocularity. “Do you remember how Haslewood laughed?” he demands, revealing to Laurience the bitter truth: that Lord Haslewood has a heart condition, which means he could drop dead at any moment: “From the frying pan into the fire!” he exclaims—demanding that Laurience do another experiment.

In fact—he wants Dick’s body. He expounds upon his plan, in which as Dick, he will inherit both the title and the family fortune; Laurience can profit from the latter. They have only to get Dick to the Institute, and Laurience can do the rest.

To which Laurience agrees…but once Haslewood has made arrangements to meet Dick there, the scientist takes him by the throat and chokes the life out of him…

Laurience makes no attempt to cover up his crime; on the contrary, he draws as much attention to himself as possible, including speaking to a uniformed police officer outside, and drawing his attention to the time.

When Dick arrives at the Institute, he assumes that “the big story” his father mentioned on the phone has something to do with the new gadget he heard Laurience mention earlier; he, and we, learn that, given Clare’s refusal to assist, Laurience has set himself to re-tool his equipment, so it can now be operated by one person. Laurience continues his monologue until Dick has his back turned—and then presses a chloroform-soaked pad over his face…

When Dick comes to, it is to find himself strapped into one of Laurience’s chairs. As he struggles in vain, Laurience gloats:

Laurience: “Don’t you see? I take your body, your name – and Clare! You? – you take the body of a man the police will hang for murder!”

The present obscurity of The Man Who Changed His Mind is hard to account for; although I suspect its title woes may have something to do with it. Apparently the in-built pun in the film’s original moniker was a bit subtle for its American distributors, who released it as The Man Who Lived Again: an unimaginative choice that may well help confuse it with almost any other of Boris’s mad-scientist films of the late 30s and early 40s. Worse still, at its various re-releases the film was lumbered with a series of other alternatives – The Brainsnatcher, Body Switch, and (heaven help us!) Dr Maniac – which probably contributed to its eventual slip through the cracks. (Annoyingly, it is almost impossible to find any advertising art using the film’s original title.)

Yet there are plenty of signs that The Man Who Lived Again was originally intended as something of a prestige production—not least that it emanated from Gainsborough, of all unlikely sources. Though this is very much a “Boris Karloff film”, for once Boris wasn’t left to carry everything on his own, but was instead given a quality supporting cast to work with. The film was directed by Robert Stevenson (who was married to Anna Lee, to which we may attribute the film’s overabundance of loving close-ups of its leading-lady), with cinematography by Jack Cox and production design – the latter one of its real strengths – by Alex Vetchinsky.

But it is the screenplay which is most responsible for the success of The Man Who Changed His Mind. Here we find three familiar names: L. du Garde Peach, who also worked on Karloff’s first British horror film, The Ghoul, as well contributing to The Tunnel; John Balderston, who wrote the screenplay of The Mummy, in addition to his script-doctoring of Dracula and Frankenstein; and, perhaps most significantly, Sidney Gilliat.

It was likely the latter who was responsible for this film’s careful balancing of its horror and humour: as his later partnership with Frank Launder would illustrate, Gilliat was a master of using comedy to heighten, rather than to dissipate, suspense. We see this in The Man Who Changed His Mind, which is a film that walks a difficult tightrope—treating its bizarre central premise quite seriously, yet offering plenty of humour as well, without ever straying into the realm of the “horror-comedy”. It also manages a genuinely complex and tightly-knitted plot in spite of its brief-running-time; so much so that a second viewing may be necessary in order to appreciate fully just how cleverly structured and genuinely witty this film is.

However—with only just over an hour to work with, something had to give; and most unfortunately (at least from my point of view) it gave with respect to its heroine. That second viewing, if not the first, brings to light the dismaying reality that for all of Clare Wyatt’s professional qualifications, she doesn’t actually get to do any science at all! Overall we see more of her as a surgeon than as a scientist—and washing coffee-pots more than either.

The more we think about, the more it becomes evident that Dr Laurience never really needed an assistant at all. Laurience himself finally assigns quite a different motive to his sending for Clare; while in plot terms, it is not her scientific expertise that matters, but her position as catalyst, bringing Laurience and the Haslewoods together.

But while this is a distinct bummer, all is not lost with respect to Clare. The film ultimately comes down on her side in all of its gender games—including a delicious bit of role-reversal at its climax, which finds Clare rushing to the rescue of the imperilled Dick. We might also care to note that while Clare is presented as genuinely dedicated to her profession(s), Dick is shown as merely playing at his work, while he schemes to get married. There’s not much question here as to who is the stronger personality; and it isn’t hard to imagine Clare putting her foot down about her work even after she and Dick take the plunge. I for one look forward to the day when Lady Haslewood takes over the running of the Haslewood Institute…

But though she makes a fine leading-lady, Anna Lee is somewhat disadvantaged by being outside the outrageous personality switches that dominate the second half of The Man Who Changed His Mind. The film becomes a great gift to its male cast-members, each of whom is given the chance to, in effect, play a dual role; at least a dual role.

The climactic sequence, which finds Boris Karloff playing John Loder playing Dick Haslewood, and John Loder playing Boris Karloff playing Dr Laurience, is marvellous; but even this is overshadowed by the outrageous plot-manoeuvring which finally gives us Frank Cellier playing Donald Calthrop playing Clayton playing Lord Haslewood. In fact, Cellier pretty much steals the film here: the scenes which find Clayton in his new body adjusting to the advantages and disadvantages of being Lord Haslewood are wonderfully funny—and vitally, are so in a manner completely organic to the plot.

Throw these into the mix with some batty science and an even battier scientist, some well-deserved satire of the Fourth Estate, and a young couple in the process of taking their era’s gender stereotypes and turning them inside-out, and the result is tiny gem of a film that deserves to be much better known.

Click here for some Immortal Dialogue!

♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦

This review is for Part 1 of the B-Masters’ 20th anniversary celebration!

“Doctor Maniac”?

“DOCTOR MANIAC”????

LikeLike

I know… 😦

LikeLike

Hmm. Be a scientist, learning amazing new things… or marry a reporter (albeit, one with prospects) and give all that up to become a household manager. How could any woman hesitate for a moment?

Dennis, that’s Dr David Maniac of the Hampshire Maniacs, an old and well-respected family. Well, a cadet branch, the Maniac-Bodysnatchers.

LikeLiked by 3 people

And we’re seriously not supposed to.

Contemplate THAT on the Tree of Woe…

LikeLiked by 1 person

And one who’s said “I hate strong minded women” – oh, so why do you want to marry her? Wouldn’t be to crush the life and soul out of her, hmm?

LikeLike

Strong-minded enough to say ‘no’ to him. 🙂

Whatever general attitudes at the time, in this case at least he’s not serious. (And not capable of doing it if he was!)

LikeLike

You WOULD have a new review up right when I don’t have time to read it…

LikeLike

Well you can’t say now I didn’t give you plenty of time, sigh…

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Mike's Movie & Film Review.

LikeLike

“They called me MAD! They called me INSANE!

…And they were RIGHT!” — Megavolt

LikeLike

Well yes, a research institute and funding is nicer than a basement lab but why settle for that when you can have the true dream of every mad scientist, a Pacific island volcano lair!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Liz, I may have already shared this irrelevant yet moderately interesting tidbit of lost mad science with you, but just in case:

According to the Tod Browning biography “Dark Carnival” (by David Skal and Elias Savada), in the late 1920s, Browning had an idea for a Lon Chaney film which would involve “the transplanting of women’s heads onto apes, and vice versa.” However, it was never made, in part because Browning drew a blank on why Chaney’s character would do such a thing.

[]

[]

[]

[]

[]

[]

[]

[]

[]

[]

[]

[]

Take it, Dr. Forrester:

“Why?! Because it’s SCIENCE, that’s why!”

😉

LikeLike

Is this movie the origin of the brain-switching trope involving two people strapped into chairs wearing helmets with wires and stuff coming out? If so, it’s amazing that it’s so little known! I’ve seen the trope soooooo many times, usually played for comedy. I think it was done on the Flintstones, Futurama, Gilligan’s Island and who knows what else!

LikeLike

A version of it appears in the 1925 Lon Chaney vehicle, The Monster, but under circumstances in which I think we’re meant to understand that it wouldn’t actually work (even within the context of the film), but is rather the clincher proving once and for all that the mad scientist genuinely is MAD.

LikeLike

Is that you Mr. Ashlin? Just curious.

LikeLike

It was. I hope you didn’t blink? 🙂

To be clear, we see the chimps in their wired metal helmets but by the time it’s done to humans most of the business goes on in separate compartments and behind closed doors, as per the screenshot.

On the other hand though the film itself has plenty of humour, this aspect of it is played completely straight.

LikeLike

I can’t help hearing the phrase “brain expert” in Mr. Gumby’s voice.

LikeLiked by 2 people

“a gathering of “the scientific community””

Those seem like they’d be great places to meet highly intelligent women. Is there a website somewhere that provides dates and locations for gatherings like that? 😉

Seriously, though, I’d genuinely like to know. Thanks.

LikeLike

I imagine they take turns hosting them in their respective secret labs.

I mean, I am assuming we want highly intelligent women of a type with the proprietor of this site, yes? I mean, who wants a non-mad scientist?

Turning to the movie itself, it sounds pretty fun. I will have to make a point to get ahold of it. Ever since our dear Lyzzy pointed me to The Walking Dead years ago, I make it a priority to see any Karloff movie she enjoys that I have not heard of previously.

LikeLike

This movie is a lot of fun, head and shoulders above Karloff’s later mad scientist flicks, in my opinion. I have a DVD set of all of the Columbia ones that came a few years later, and seemed to have spawned out of this one, and while they all have interesting moments, none of them really hit on all cylinders like this one does. The strong woman lead is a big part of the appeal – it’s a trend I’ve noticed in a few British horror pictures of this period – I think Dark Eyes of London and Chamber of Horrors both do very well by the women in the cast if I remember correctly.

LikeLike

Hi, Ben – welcome!

I agree, it’s much better than the Columbia mad doctor films but has obviously been lost in the shuffle of their greater fame / availability.

The script doesn’t do Greta Gynt too many favours in Dark Eyes Of London but it does let her rescue herself at the end, so that’s one thumb up at least.

LikeLike

Pingback: THE MAN WHO CHANGED HIS MIND (1936) Reviews of Boris Karloff mad doctor movie – iTube Movie