“We haven’t seen the end of them. We’ve only had a close view of the beginning of what may be the end of us…”

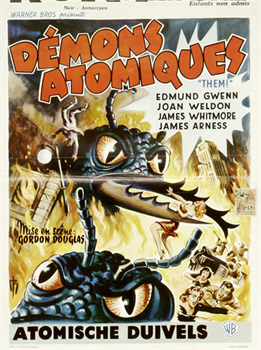

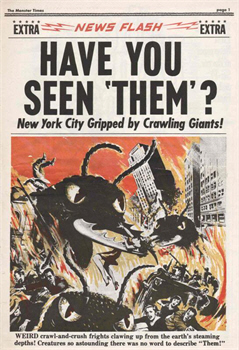

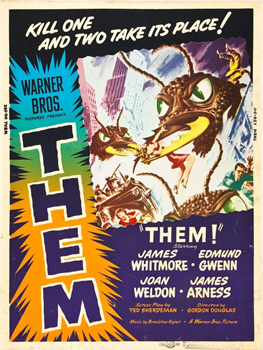

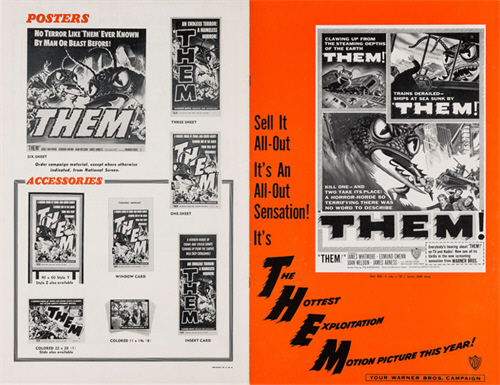

Director: Gordon Douglas

Starring: Edmund Gwenn, Joan Weldon, James Whitmore, James Arness, Sandy Descher, Onslow Stevens, Sean McClory, Mary Alan Hokanson, John Close, Don Shelton, John Maxwell, Fess Parker, Olin Howlin

Screenplay: Ted Sherdeman and Russell S. Hughes, based upon a story by George Worthington Yates

Synopsis: In the desert of New Mexico, Sergeant Ben Peterson (James Whitmore) and Trooper Ed Blackburn (Chris Drake) of the State Police conduct a search under the guidance of a spotter pilot (John Close). The three men are about to conclude that the report of a wandering child was mistaken when the pilot sees a little girl (Sandy Descher) some distance off the road, and directs the others to her. Peterson hurries towards the child, who is in her dressing-gown and carrying a damaged doll; she pays no attention to his calls and, when he approaches her, remains completely unresponsive. As he is carrying her back to the car, Blackburn takes another call from the pilot, who has spotted a trailer and a car a few miles away, though he could see no people. At the scene, the police officers discover that one wall of the trailer has been ripped open, while the inside is a wreck. Torn and bloody clothing lies on the floor, along with some scattered banknotes. Peterson also finds a handgun from which all six shots have been fired and, in a cupboard, a fragment of the little girl’s dressing-gown and the broken part of her doll; while outside, in the desert sand, Blackburn discovers a strange print, of no animal either man can identify. Bizarrely, the scene is scattered with spilled sugar cubes. The men call an ambulance and an evidence team to the scene: the latter dust for prints and make a plaster-cast of the mark in the sand. As the little girl is being loaded into the ambulance, an eerie, high-pitched sound sweeps across the desert. The men look around, not noticing that behind them, the little girl is sitting up, her eyes wide with terror… Peterson and Blackburn then make their way to the local general store to see if the proprietor knows the missing people or has any other information. They find instead a repetition of the trailer wreck; they also find a broken shotgun behind the counter, and a bloodied body in the storm-cellar. Sugar has again been spilled at the scene, and no money has been taken. A call is placed to the evidence team: Blackburn offers to wait for them, so that Peterson can be at the hospital when the little girl wakes up. Shortly after he departs, Blackburn hears the same eerie sound. He walks out into the falling night to investigate its source—and then screams… The people missing from the trailer – a married couple and their young son – are identified as the Ellinsons. The man was a federal agent on leave, which brings to the scene FBI agent Robert Graham (James Arness). He is just as baffled as the local officers, but offers to send the plaster cast of the strange print to Washington. The county medical officer (John Maxwell) then delivers the results of his autopsy on Gramps Johnson: not only was his body crushed and broken, but it was full of formic acid… To Graham’s bemusement, two scientists from the Department of Agriculture are sent to assist the investigation; he is even more bemused when he meets the elderly Dr Harold Medford (Edmund Gwenn) and his daughter, Dr Patricia Medford (Joan Weldon). Though his orders are to cooperate fully with the scientists, Graham becomes irritated by their secretiveness; however, they insist that their theory must be properly investigated before they tell anyone what it is. Having read all the reports and examined the evidence, the Medfords’ first stop is the hospital, where the Ellinson girl is still unresponsive. Learning that all conventional approaches have either failed or are considered inappropriate for a child, the elder Dr Medford tries holding a vial of formic acid beneath her nose. After a few moments, the child reacts violently: in a state of utter terror, she shrieks, “Them! Them!…”

Comments: Okay—we may as well get this out of the way at the outset:

The ants are a tiny bit shonky.

That’s about as close as I’m going to get to actual criticism of Them!, the first ever “big bug” cautionary tale and one of the finest, if not indeed the finest, of the 1950’s many extraordinary science-fiction films.

While we now consider that decade as the pinnacle of screen science fiction, it is a curious fact that almost all of its first genre offerings, even some of those we now consider to be “classics”, were produced independently, with the major studios strangely dilatory about competing for this new audience market. For instance, though we now think of Universal as a major player in this area, as it had been for horror in the 1930s, it wasn’t until 1953’s It Came From Outer Space that the studio got into the new genre game; while it was a relative newcomer, 20th Century Fox, that first took the plunge with 1951’s The Day The Earth Stood Still. (This, even though neither TCF nor its predecessor, Fox, had produced a single genre film during the 1930s!)

Even more strangely, it was Warners that followed 20th Century Fox into action—although, as had been the case in the 1930s, reluctantly, and with considerable doubts over the wisdom of its actions. The Warners executives didn’t really understand this new trend, beyond the salient point that the public was eating it up and paying good money to do so. The studio was still reluctant to commit significant resources, however, and so compromised by picking up for a reasonable sum an independent production which itself had been inspired by the almost absurdly profitable re-release in 1952 of King Kong. The first American monster movie of the 1950s and its first “atomic scare” film too, 1953’s The Beast From 20,000 Fathoms went to make over $5 million dollars at the box-office.

This was enough to convince even the Warners executives – mostly – who committed to producing their own science-fiction film during 1954. In fact, Them! was first conceived as a fairly prestige production, intended to be shot in colour and in 3D. (Some of the still-extant advertising art was clearly designed to promote a colour film.) The latter compelled the film’s monster ants to be constructed full size, since optical effects and 3D photography just didn’t mix (a lesson painfully and expensively learned during some earlier 3D productions). Warners did toy with the notion of hiring the man whose work on The Beast From 20,000 Fathoms had been so instrumental in that film’s success, Ray Harryhausen; but in the end handed the task over to its own studio technicians.

Almost at once, however, things began to go wrong. Jack Warner, who didn’t “get” science fiction any more than he ever “got” horror, thought a film about giant ants was frankly stupid and probably destined to fail. Cold feet set in not long after he signed off on the production of Them! The 3D shooting went first, and then the colour photography; widescreen was at first offered as a compromise, but then even this was yanked away from the production team.

The promised bells and whistles having vanished into the ether, the budget was then cut, and a rookie producer in David Weisbart assigned to oversee the project—reducing Them! to the level of a standard 50s B-film.

Or so Warners intended. Fortunately for all of us, Gordon Douglas didn’t get the memo. Despite having to stand by while the prestige production he had signed on for was lopped and cropped into a shadow of itself, Douglas lost none of his enthusiasm for the project. On the contrary—he set himself to embarrass his bosses by proving to them just how good a film about giant ants could be.

The director’s partner in crime was Ted Sherdeman, who was originally assigned as the film’s producer but became another casualty of the budget-cutting. George Worthington Yates had written the original treatment for Them!, but was unable to turn it into a workable script. When his replacement, Russell Hughes, sadly died suddenly during pre-production, Sherdeman stepped in. His completed screenplay is a lean and intelligent piece of writing, full of quiet but powerful touches whose impact is sometimes not fully felt until a second viewing. It was also he who was responsible for the story’s settings, after (as I am sure no-one will be surprised to hear) Yates’ treatment involved giant ants attacking New York.

In fact, Warners’ corner-cutting ended up having quite a number of inadvertent positive consequences. I don’t think that Them! would have worked in colour one-half as well as it does in black-and-white: Sid Hickox’s moody cinematography is one of its great strengths, contributing to both its serious tone and its growing suspense. There is some marvellous chiaroscuro here, particularly the way the light is repeatedly broken up with bars and checks; while the opening location shooting sets the tone for what is to follow. The film overall has a a terse, pseudo-documentary style which is significantly responsible for its effectiveness; the second half of it plays out almost like a police procedural, although by then the mystery is not “what?” but “where?”.

However, another contributory factor to the impact of the film is that the lower budget also meant a lack of big-name stars. Here the film really lucked out, gathering together instead character actors whose performances are low-key almost to the point of invisibility, but whose work as an ensemble is exemplary, giving at every moment the impression of real people dealing with a real crisis.

And in that, we identify the main reason that this film still works so well: it takes itself seriously without being solemn, and it never lets up. Only the very briefest of comic and romantic interludes are included, an absence not only welcome in itself, but which emphasises the magnitude of the danger confronting the characters.

Them! opens – a little jarringly, it must be said – with a solitary reminder of the film’s initial conception: against a black-and-white backdrop, the title zooms forward both in colour, red and blue, and written in a style we now recognise clearly as standard 3D format. (Rumour has it that Gordon Douglas paid for this touch out of his own pocket, as another nose-thumb at the studio.)

At once we find ourselves in the desert of New Mexico. Coincidentally, Them! and It Came From Outer Space were in production at exactly the same time during the first part of 1953 – and were released within a fortnight of one another – neither therefore copying the other but both together establishing the desert as one of the decade’s fundamental science-fiction settings.

While It Came From Outer Space probably uses the desert better (but then, the entire film is set there), these opening scenes of Them! do succeed in capturing the both stark beauty of the landscape and, more importantly in context, its enormity and sometimes frightening emptiness. Despite the overt setting, the location shooting for Them! was carried out around Palmdale in California.

A small plane crosses the sky as a State Police patrol car drives along a dirt road. The three officers are following up what seems an improbable report of a child wandering alone in the desert. Just as they are about to call off their search, the pilot does indeed spot a young girl walking alone some distance from the road. Under the pilot’s direction, the patrolmen spot her; Sergeant Ben Peterson jumps out of the car and calls to her but she pays no more attention to him than she did to the circling plane, continuing to stare straight ahead of herself as she moves in a straight and rather hurried line.

A bemused Peterson runs after her and stops her, but she remains unresponsive to both his questions and a hand waved before her blank eyes. Peterson carries her back to the car just as his partner, Trooper Ed Blackburn, is receiving another call from the pilot, who reports that he has spotted a car and trailer pulled up on the side of the road a few miles away, although no people are visible at the scene.

The two police officers go to investigate, Blackburn driving while Peterson cradles the little girl in his arm. She falls asleep, leaning back against her rescuer.

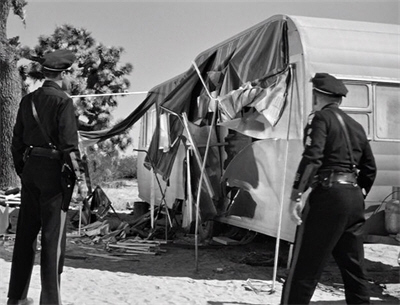

At their destination, the police officers find a scene of devastation and mystery. One side of the trailer has been completely ripped open, and the inside is wrecked. No occupants are present, but Peterson grimly observes some torn and bloody clothing and a fully discharged handgun. He also finds some banknotes scattered about, suggesting that whatever happened, the motive wasn’t robbery.

Peterson’s most disturbing discovery, however, is made within a small cupboard beneath one of the trailer’s bunks: inside he finds the missing piece of the little girl’s broken doll, and a fragment of cloth ripped from her dressing-gown. Blackburn, meanwhile, has made two other curious finds: a print in the sand outside that he cannot identify, and a scattering of sugar cubes all over the scene. The baffled police officers call an ambulance and an evidence team to the scene.

There are a couple of moments in the scene that follows that seem throwaway in context but which in fact are important in establishing two of Them!’s major themes. The first of these is Peterson’s almost-cliché inquiry about one of the newcomers’ kids, and the equally standard reply of, “There’s another on the way.” Throughout Them! we find an underlying insistence upon the value of human life, and it is to this end that children play such an unusually prominent role in the working out of its plot.

The introduction of the lost and traumatised little girl at the beginning is bookended at the film’s climax, which is built around the attempted rescue of two more threatened children; bookended likewise by Ben Peterson’s critical role in each subplot. The film is unusual and striking in its willingness to place children in danger – and worse – but this note of grim reality is counterbalanced by the adult characters’ dogged insistence that no price is too high to pay to preserve a child’s safety. (A minor character who suggests otherwise is shot down in no uncertain terms.)

The other point of importance here involves the technician whose task is to make a plaster cast of the strange print in the sand. (I say “technician”— Of course the whole team rolls up wearing suits and ties and hats and polished shoes!) When Peterson asks what he makes of it, he has no answer but a blank look and a shake of the head. This willingness to admit ignorance is unusual, and it paves the way for the introduction of the film’s real experts, who are handled by the script in a manner that is remarkably refreshing.

Having urged haste on the technician, as a sandstorm is building, Peterson looks on as the little girl is loaded into the ambulance. Suddenly, a strange, high-pitched sound sweeps across the scene from out of the surrounding desert. Peterson and the ambulance attendant look around, seeking its source—and do not see the little girl sit up behind them, her eyes wide with fear. As the sound dies away, she lies down again…

One of the unsung heroes of Them! is sound designer Francis J. Scheid, who succeeded in creating a genuinely unnerving aural signature for the film’s monsters, which is frequently used to suggest their unseen presence. This eerie sound is actually a mixture of animal calls, chiefly that of the bird-voiced tree-frog blended with those of the wood-thrush and the red-bellied woodpecker, with their speed and pitch altered.

Peterson and Blackburn then move on to the nearest habitation, the general store owned by “Gramps” Johnson—only to find a horrifying repetition of the devastation at the trailer. This time there is a body at the scene; there is also a shotgun which has almost been snapped in two, and a barrel of sugar that has been broken open. Over the spilled contents of the latter scurry a hoard of small ants…

This is a genuinely creepy scene: night is falling as the officers arrive at the scene; their search is conducted under a swinging ceiling-light that reveals and conceals the various horrors, and accompanied by the moan of desert winds. It also contains another of the film’s subtle thematic touches: the radio is playing the news as the men walk in; we don’t hear the first story clearly, but it is ominously political in tone. However, this is followed by a clearly-heard WHO report on disease eradication, introducing an important note of, “Yeah, things are bad; but we’re working to make them better.”

Sickened and confused, Peterson can only suggest that the evidence team be called in, to do what they can at the scene. Blackburn offers to wait for them, freeing Peterson to drive into town to the hospital, to be there when the little girl wakes up and, hopefully, starts talking.

Peterson receives this offer gratefully and departs. He has been gone only moments when the Blackburn hears the same high-pitched sound as earlier, near the trailer. Understandably apprehensive, the young cop unholsters his gun, switches off the lights and turns off the radio, waiting for—he doesn’t know what. He ventures out into the night—where he confronts something at which he fires his gun unavailingly…and then screams in terror and agony…

Some critics find the opening sequence of Them! to be overlong and/or too slowly paced. I couldn’t disagree more: I think it does a wonderful job in setting up the magnitude of the danger with which the characters will be confronted – even though, at the moment, we only know a relatively minor aspect of it – as well as making marvellous use of its atmospheric settings.

Furthermore, as noted, these scenes are studded with touches that throughout the film will become important themes. And we can set beside these the demise of the unfortunate Blackburn: a minor character only, but one who has already earned our respect; his death is a warning that this film won’t be wearing kid gloves in the handling of its characters.

Of course—some of the negative reaction is in the monster-movie sense of, “We know what the ‘unknown’ threat is, get on with it!” However, it should be noted that, in 1953, people by and large did not know: the film’s advertising was designed to disguise its menace – partly to increase suspense, partly because of Jack Warner’s embarrassment over giant ants – and the critics of the time mostly played ball, not giving it away in their reviews. And even though we know now, there is never a point in these early scenes where the characters’ own mystification isn’t wholly justified, or strikes us as exaggerated.

This latter point is underscored when we cut to the headquarters of the State Police, where the frustrated officers’ knowledge that they’re doing everything they can is offset by their equal awareness of the futility of “standard procedure” in a case like this. In addition, Peterson is consumed with guilt over Blackburn’s death.

There is a chilling moment here, when we learn the identity of the people from the trailer: fingerprint evidence has identified an Alan Ellinson from Chicago, holidaying, “With his wife and two children.”

Ellinson’s fingerprints are on file because he was an FBI agent; his disappearance therefore brings to the scene a representative from the local field office, Robert Graham.

James Arness was still struggling to establish himself when he was cast in Them! This was his first starring role in a film produced by a major studio after several years of bit parts and small supporting appearances. We might be inclined to feel, however, that things didn’t quite work out here as Arness may have expected, despite his overt casting as the film’s hero.

For one thing, he found himself with an in-film rival; possibly an unexpected one. James Whitmore initially found himself intimidated by Arness, who famously stood a full 2 metres tall and tended to dominate the frame without trying. To counter this, Whitmore resorted to lifts in his shoes—but he also resorted to throwing in little bits of business whenever he shared the screen with his co-star: nothing overt or out of character, perhaps just a shifting of position or a change of expression or a gesture with his hands, but all tending to draw the viewer’s eye. Knowing this in advance adds an amusing if insidious touch to watching the film because, guess what? – it worked. The still-relatively inexperienced Arness never stood a chance.

(Arness’ payoff came later: his performance here was significant in his casting in Gunsmoke.)

But it is the way the two characters were written that had the greater impact. For one thing, even if Robert Graham can be considered the film’s hero – or more correctly, even if he occupies what would normally be considered that role – he is hindered by being in addition the film’s “Ordinary Joe”, the guy who has to ask the scientists to “speak English” and to have things explained to him. Even though Graham is an FBI agent, he ends up as something of an outsider among the group of professionals who hold the story’s centre: not because of any failing on his part, but rather because for much of the film he ends up following the orders of others who better understand the situation; and while he does make an invaluable contribution in that respect, he tends to be reactive rather than taking the leading role we tend to expect.

In this respect, Peterson is an outsider and a follower too—except that we’ve already followed him through the opening sequence of the film, which highlights his quiet professionalism, but also his warmth as an individual; something seen in both his interaction with the little lost girl, which is full of genuine tenderness and concern, and his silent grief over Ed Blackburn’s fate. Because of these scenes, the audience becomes invested in Peterson as it never has a chance to do with Graham, whose late arrival on the scene leaves him at a disadvantage. The film eventually plays fair with him, though: as the ants are tracked across the country, it is Graham who takes the lead in the investigation.

Graham’s arrival almost coincides with the visit of the local medical examiner, who has come to give his autopsy report on Gramps Johnson—who could, we learn, “Could have died in any one of five ways.” Four of them are forms of massive trauma; the fifth is an enormous dose of formic acid…

(“Ah-HA!” I believe I cried out loud at this point the first time I ever saw this film, at the age of seven or eight. I was such a little nerd…)

Graham then makes the most immediate and significant impact upon the investigation of all these mysterious events by sending the plaster-cast of the strange print to Washington. This gets a response that no-one is expecting: a telegram announcing the imminent arrival of the Doctors Medford – two of them – on an army plane.

Graham and Peterson head for the airport, neither one able to guess why the Department of Agriculture is getting involved in their mystery. First off the plane is the elderly Dr Harold Medford; but it is the second Dr Medford who captures the attention of the two other men—chiefly because her rather tight skirt gets caught as she is climbing down the ladder to the tarmac, and so displays to them the lower half of an excellent pair of legs.

In one respect, the Medfords, senior and junior, are Them!’s most cliched characters: we’ve seen the elderly scientist / beautiful young companion duo in more science-fictions than we could name, even if we cared to try. What’s more, there’s a whiff here of the androgynous-name-game too: Dr Medford Jr is called Patricia; and you better believe it isn’t very long before she’s insisting, “Call me Pat!”

But this introduction is deliberately misleading, because there’s something different, and vitally important, about Patricia Medford: she isn’t just Dr Medford’s daughter; she isn’t his secretary; she isn’t his assistant. She isn’t just The Chick. On the contrary, she is a fully qualified scientist in her own right, her father’s professional colleague.

Meanwhile—though likewise there is a whiff here of that other stand-by, “the absent-minded professor”, Dr Harold Medford is tunnel-visioned rather than absent-minded: so focused upon his theory of what is happening in the desert, and what it will mean if his theory is right, that the usual niceties of human interaction are for the moment beyond him.

Though it was probably just, or predominantly, a matter of copying The Beast From 20,000 Fathom‘s casting of Cecil Kellaway as a rather cuddly older scientist, the presence of Edmund Gwenn represents something of a coup for Them! It occurs to me – and the thought delights me – than Gwenn is used here as Shimura Takashi would be in Gojira, made the same year: an established and popular character actor with strong credentials, given the task of lending credibility and gravitas to an unbelievable story. As Dr Medford Sr, Gwenn has to do most of the film’s explaining—first to the police and the FBI, then to the army and the government; but always, of course, to the audience. It is also he who is responsible for most the film’s humorous moments; but this is organic to his character, rather than something written in just to lighten the mood. On the other hand—he also gets the film’s grim closing line…

The Medfords are offered a stop at their hotel, but insist upon a trip to police headquarters instead, so that they can review all the evidence. This provokes another “Ah-HA!” moment:

Dr Medford Sr: “Tell me: in what area was the atomic bomb exploded? I mean the first one, in 1945?”

Robert Graham: “It was right here, in the same general area. White Sands.”

(…although I don’t think I said “Ah-HA!” to that when I was seven or eight; and if I do so now, truthfully I think it’s less for it’s real-world implications and more for the punishing reuse as stock footage of that shot from the opening of Rocketship X-M.)

Their significant mutterings and ignoring of his questions by the Medfords soon riles Graham, who reminds them tartly that he and Peterson are assigned to the case too. Dr Harold insists that their theory must be furthered explored before they voice it, however, and to that end requests that they go to the hospital, so that he can see the Ellinson girl—

—thus setting up one of 50s science fiction’s most indelible moments.

Every time I watch Them! I’m struck all over again by the performance of young Sandy Descher, seven years old at the time—and can only admire the skill (and probably patience) of Gordon Douglas, and whoever may have helped, in getting it out of her. The little girl’s state of catatonia, particularly the lengthy moments when she doesn’t blink, is unnervingly convincing; and the only thing more so is how she comes out of it…

In fact—these days what Ms Descher’s performance puts me most in mind of is Susan Backlinie’s in Jaws: each a small but perfect contribution, without which the films that contain them would not have nearly so much of an impact.

At the hospital, Dr Harold learns from the doctor in charge of the case that none of the standard treatments have been considered appropriate for the child: she’s too young for curare for her muscle spasms, and narcosynthesis is pointless until she overcomes her aphonia. (G-Man Graham knows what “narcosynthesis” is…hmm…but needs “aphonia” explained.) The nurse concludes that a cathartic shock is the only thing that might bring her out of her state of withdrawal, and Dr Harold agrees. In fact, that’s why he’s there.

On their way to the hospital, the Medfords collected some formic acid from a drug store, and now Dr Harold pours some into a glass and moves it back and forth beneath the little girl’s nose. For a few moments there is no response. Then she moves slightly, blinking—and then screams:

“THEM! THEM! THEM!”

She leaps from her chair and dashes into a corner of the room, desperately seeking safety as she shrieks and cries in terror; and once again, it is Peterson who takes her comfortingly into his arms.

As the child sobs despairingly against the police officer’s shoulder, Dr Harold picks up his hat and suggests that the next step of their investigation should be a visit to the desert:

Robert Graham: “It’s getting pretty late, Doctor.”

Dr Harold Medford: “Later than you think…”

The threatened sandstorm is still blowing when the group arrives at the point from which the car and trailer have now been removed. Peterson shows the others where the print was found, then goes with Dr Harold when he asks to look around. This allows Graham to vent to Dr Pat about his frustration with, “That old— Your father.”

“That old man,” retorts Dr Pat, “as you started to call him—” (uh, yeah: I don’t think that is what he was about to say) “—is one of the world’s greatest myrmecologists!”

Ah, dear. Of course this is also the “Call me Pat!” scene, and of course it signals the start of a romantic attraction between Graham and Dr Pat, even though there’s no real reason why there should be one—except that such a situation was more or less obligatory at the time. However, to the film-makers’ credit the relationship is kept as lightly sketched-in and unobstrusive as possible, and never supersedes the crisis as the focus of the film’s attention. Moreover, more time passes in Them! than is overtly apparent, with mentions of “weeks” and “months” while the investigation is being conducted, making it a lot less exasperatingly perfunctory than usual.

Despite this shifting of their personal connection, Dr Pat holds to her father’s policy of silence and evades Graham’s questions. The two are interrupted by a cry from Dr Harold, who has found another print in the shelter of a small tree. He measures it, and he and Dr Pat do some rapid mental arithmetic:

Dr Harold: “Over 12 centimetres!”

Dr Pat: “That would make the entire—”

Dr Harold: “About two-and-a-half metres in length; over eight feet!”

(The use of the metric system is a nice touch, but there is one bit of silliness here—even if the Medfords weren’t father and daughter: Dr Harold’s habit of calling Dr Pat “Doctor”. Trust me, it isn’t scientists who insist upon being addressed by their titles…)

(And yes, I’m doing it; but then, you know why I’m doing it…)

Dr Pat obeys her father’s instruction and goes looking for more prints, while Dr Harold deduces “direction of travel” from the one they have. By this time Peterson is as exasperated as Graham, but Dr Harold continues to hold his cards close to his chest. They, he tells them rather tactlessly, are concerned with a local matter; whereas he is concerned with something incredible, which may threaten a nation-wide panic…

Meanwhile, Dr Pat’s search has led her to the base of a sandy ridge, where she kneels to smooth away the material surrounding another ominous mark in the sand. At that moment, there is a strange sound from nearby. Dr Pat looks around, trying to locate its source—but does not immediately see what is looming over her from the top of the ridge…

Well. Yes. A tiny bit shonky, it must be admitted; which the film tacitly addresses by shooting the ants either through the haze of a sandstorm or in the dark. The eyes in particular are wrong, being human-like rather than the correct compound design, which frankly would have been much more creepy. Apparently they were made that way intentionally, so that the cavity beyond could be filled with coloured liquids that would shift and change as the ants moved—back when the film was being shot in colour, of course. In black and white, the effect is rather unfortunate.

However, the main practical defect is the floppiness of the ants’ antennae—particularly because the film draws attention to them. These should have been made rigid but articulated, so that they could have been held steady or manipulated by wires. Instead they flop around in a distracting way that interferes with suspension of disbelief.

Still— The very fact that the film’s giant ants are life-sized constructs – which is to say, eight feet long – has some real benefits too; practical effects always do. The ants are consequently an immediate physical menace in a way that no optical effect could ever quite achieve, and can be made to perform physical tasks that would otherwise have been out of the question.

Dr Pat here executes one of cinema’s most forgivable scream-and-trips. (Not least because she’s still in her travel clothes, a pencil-skirt and high heels!) Fortunately, the others have heard the sound too – Peterson of course has heard it before – and come rushing to the rescue. Peterson and Graham begin shooting at the ant, but to no avail until Dr Harold shouts at them to aim at the antennae, so that the creature will be incapacitated. The two men succeed in this, and Peterson then polishes the ant off with a tommy-gun (!) from his patrol-car.

“What is it?” demands Peterson blankly; though it is doubtful whether Dr Harold’s answer – “Camponotus vicinus, one of the family of Formicidae” – leaves him any the wiser. Realising this, Dr Harold adds simply, “An ant.”

And of a rather common species, which was probably intentional. It should be said that the overall body-shape in the models is reasonably correct, although the mandibles are exaggerated—or rather, left in the extended position at all times. (Later films would likewise have their shark in a permanent feeding posture.)

Peterson and Graham express their incredulity, but the evidence is plain; Graham even notices the odour of formic acid.

One of the things at which Them! excels is what we might call the “indirect-gruesome”: it repeatedly provides enough evidence for the audience to realise for themselves what has happened without it being spelled out—like that reference to the Ellinson family consisting of mother, father and two children.

Here, Peterson speaks numbly of Ed Blackburn, the Ellinsons, and Gramps, even as Dr Harold goes into a purely biological lecture about how members of this species use their mandibles to “rend, tear and hold”, but kill by injecting formic acid with their stinger; we are left to fill in the mental images for ourselves.

Dr Harold here also joins the dots between the earlier mention of “White Sands” and the existence of this “incredible mutation”.

To the horror of the two laymen, the Medfords then speak of the necessity of finding the nest; their words underscored by another burst of what Dr Pat calls the ants’ stridulation—communication by sound (which is produced by the ants rubbing two segments of their bodies together, though the script doesn’t get into that).

Dr Harold: “We may be witnesses to a biblical prophecy come true: ‘And there shall be destruction and darkness come upon creation, and the beasts shall reign over the earth’…”

Yeah. We wish.

From here, much of Edmund Gwenn’s dialogue consists of fun – and not so fun – facts about ants and their habits. There is one lecture, when he must impress upon the government the magnitude of the danger that the giant ants represent, but for the most part what we need to know is scattered into his conversation with the others who become involved in trying to deal with the situation.

By the next day, the military is involved. Two search helicopters are sent out to find mounds that might indicate an ants’ nest—Dr Harold and Peterson in one, Dr Pat and Graham in the other. It’s Dr Pat who spots the ominous opening in the ground. As the helicopter flies closer so that she can photograph the scene, a single ant emerges from the nest intent upon tidying up: over the edge of the mound, it drops a rib-cage, which rolls down the side and lands upon an entire pile of stripped-bare bones…including unmistakably human bones. The rib-cage comes to rest next to a gun-belt and holster…

Of course the military – in the form of one General O’Brien – just wants to go in all guns blazing, or at least with a bomber squadron, and wipe the ants out. Dr Harold responds with a pitying tsk-tsk, explaining that the ants forage at night: any offensive foray must take place in the heat of the day, when the ants are below ground.

O’Brien goes along with this—not least because, “I’ve been instructed to take orders from you; give you anything you ask for”, a point I shall return to later.

But he also does it because Dr Harold has an alternative plan. They cannot risk any of the ants getting away, the scientist explains: they must find a way to drive the colony deep underground.

In proposing this plan, Dr Harold first rejects the possibility of flooding the nest, since the others tell him that an adequate water supply will be impossible; mentioning in passing that ants “breath through their sides”.

Yes. Yes, they do.

Ants of course don’t have lungs: they breathe through spiracles, openings in their exoskeleton, one pair in each segment of their bodies. The spiracles connect with a network of tracheae which permeate the entire body, getting narrower as they penetrate the various organs and tissues so that oxygen is obtained by diffusion. Though ants can open and close their spiracles, their breathing is an almost entirely passive process, driven by normal movements; there is no pumping mechanism.

Though this system works perfectly well up to a point, but it does have some consequences—the most important of which is to restrict the body-size of any insect that depends upon it, since the greater the body-mass, the less efficient the diffusion of oxygen.

Sigh.

I can tell you this, people—that day, many years ago, when I discovered that there was an actual biological reason why ants could not grow to be eight feet long and take over the world was one of the most emotionally shattering of my life.

It’s interesting, too, that Them! skips pretty quickly past this point, without any attempt to explain away the size of its mutations. Probably they felt this wasn’t general knowledge at the time. (Later films would often give their monster-insects a form of lungs.)

The general’s offsider, Major Kibbee, suggests phosphorus-bombing via bazooka, to which Dr Harold agrees; adding that the bombing must be followed up with cyanide gas-bombs: the gas will fall and penetrate even the deepest chambers of the nest.

O’Brien then asks how they will know that all of the ants are dead?

Dr Harold: “We go into the nest and find out.”

The bombing is carried out as planned; Peterson and Graham, forced to be passive while the Medfords are making their case, take an active role. (We gather here that Peterson is ex-military; from his behaviour later, Graham is too.) When the area has cooled – although not much – the two men venture to the opening in protective gear to carry out the cyanide bombing.

Once the fires have died out and the gas settled, preparations are made to venture into the nest. Graham looks up from hammering a climbing anchor into the ground—

—and sees Dr Pat striding towards him clad in fatigues and boots.

The tone of the confrontation is fascinating: Graham wants to protect her as a woman, which offends Dr Pat as a scientist. Insisting that greater issues are at stake than merely whether the ants are alive or dead, she argues that a trained observer is absolutely necessary and, as her father isn’t physically up to the task, that leaves her; impatiently waving away Graham’s suggestion that she tell him and Peterson what to look for:

Dr Pat: “There’s no time to give you a fast course in insect pathology! So let’s stop all the talk and get on with it.”

There’s an interjection here from Dr Harold that bears investigation: “I didn’t ask her to do it, she wanted to,” he says to the fuming Graham in a deprecatory tone, “and as a scientist myself, I couldn’t very well forbid her.” Is he suggesting that he should have forbidden her as a father, that he has fallen down on the job? (Leaving Graham, suggestively, to act as his proxy.) Maybe—but really we get the feeling that, rather than being what it “should” be, the relationship between the Medfords is on a different and more mutually respectful level, one without the power differential.

Anyhow— Dr Pat is right and Graham knows it, much as it sticks in his craw. The two of them and Peterson climb down into the nest, all three wearing gas-masks and carrying lamps; the men are armed with flame-throwers, while Dr Pat has her camera gear.

(We should note that in spite of the toe-to-toe, the three of them are by now “Pat”, “Bob” and “Ben”.)

The exploration of the nest is a logistically simple but effectively suspenseful sequence, with the three working their way around the dead ants and penetrating into the depths of the colony. At one point the three are startled by a scrabbling noise, and by a stream of falling dirt. They pause, on high alert—suddenly to be confronted by several ants, which break through a wall and lunge towards them. The men turn their weapons on the creatures, which die under the barrage of bullets and flame. Observing the nature of the cavity, Pat reasons that the original bombing caused a cave-in which both sealed these ants in, and protected them from the gas.

Finally the three locate what, under Dr Pat’s guidance, they’ve been looking for: the queen’s chamber. They also find what Dr Pat has been dreading, though the men do not as yet understand the significance of the torn-open egg-casings. After the scene has been thoroughly documented, Dr Pat issues a terse order for everything in the chamber to be burned.

Later studying the photographs, however, Dr Harold immediately sees the persistent danger, which Dr Pat confirms by confirming that they saw no winged ants amongst the dead, only workers.

In short—two queen ants escaped the nest before the bombing, and by now could be almost anywhere…

(Them! again plays fast and loose with biological reality here: Dr Harold multiplies up the possible distance travelled by the increased size of the ants, when of course at such a size they would not be able to fly at all. In fact, he himself observes that, ordinarily, queen ants travel on “wind and thermal currents”, rather than sustaining independent flight. A second bit of tampering is the observation that these ants have no larval stage, but hatch as adults directly from the egg. Presumably this was intended to escalate the immediacy of the threat.)

The action then shifts to Washington, where Dr Harold delivers a lecture – complete with supporting documentary footage – in order to convey the magnitude of the danger to the necessary Higher-Ups. As eye-witnesses to the incredible truth, Peterson and Graham are also present.

There’s a whiff of Woody Woodpecker about this, but in Edmund Gwenn’s soothing tones, it goes down easily enough.

The message, however, is grim:

Dr Harold: “Ants are the only creatures on Earth – other than man – who make war. They campaign; they are chronic aggressors; and they make slave labourers of the captives they don’t kill.”

Them! is an interesting outlier amongst the “cautionary tales” subset of 50s science-fiction film, in that on the whole it avoids overt politicising; and while it does have its moments, it tends to leave them open for interpretation.

Here, for instance— Dr Harold’s statement is one of simple fact; but at the same time, it is easily interpreted as a condemnation of that other “Them” that fixated America during the Cold War, and a call for a united and comprehensive response to the threat of “invasion”.

Yet to me it seems that most of the moments in this film that have a political aspect carry a negative suggestion. For example, the ruthless use of flame-throwers against “the enemy”, who are trapped in underground bunkers, is a disturbing image. The Higher-Ups agree that secrecy about “the invasion” must be maintained, and immediately clamp down on the flow of information to the news media; while their various actions is dealing with the immediate manifestations of the crisis could reasonably be called “a cover-up”. Their excuse for all this is their certainty that the result of informing the public would be, “A panic that no police force in the world could control,” as Ben Peterson puts it; and the few individuals who do gain such dangerous knowledge are made to pay a price…

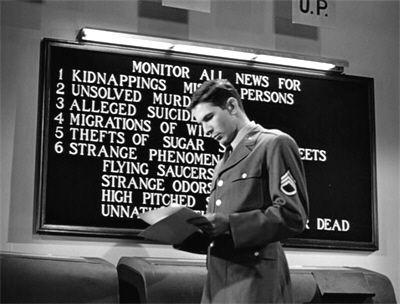

In order to gain some idea of where the queen ants may have established their nest, those in charge establish an information bureau to collate any reports of “strange phenomena”, although without those doing the collation knowing why.

One particular case involves a ranch foreman from Texas called Alan Crotty, who insists that his small plane was forced down by “flying saucers shaped like ants”—and who as a consequence is being held in a psychopathic ward.

Graham and Dr Pat head for Brownsville to interview Crotty, who they find in a state of high agitation: doggedly sticking to his story, but furious about the implications of his incarceration, and even more upset about the mortifying certainty of being laughed at.

Only – as he realises, looking into the faces of his visitors – these people aren’t laughing…

But on the other hand, the fact that they believe Crotty’s story doesn’t mean that – as he assumes – they will arrange with his doctor for his release. On the contrary:

Graham: “Your government would appreciate it if you kept him here… We’ll send you a wire and tell you when he’s well.”

And we shouldn’t be laughing either…

Soon afterwards there is news of one of the two queens, which has landed on a cargo ship at sea and taken advantage of an open hatch-cover. A wire is sent to Washington even as the crew fights a desperate but unavailing battle for their lives.

(This scene contains the first ever use in a genre film of the so-called “Wilhelm scream”, which has since by overuse become a running joke.)

There are only two survivors, who are subsequently rescued by the navy; while the cargo ship is sunk with all, uh, legs. The naval vessel is then ordered to stay at sea, so that no-one can talk about what they’ve seen.

(The ship in question is named as the Milwaukee, which according to my colleague El Santo is an error on the film-makers’ part.)

Meanwhile, Graham and Peterson are in Los Angeles, investigating the theft of 40 tons of sugar from out of a goods-train—the side of which has been ripped open in an ominously familiar manner. They go to the local police station, where a suspected night-watchman is being held; and while they are interviewing him, they get their next lead. In the next room is a distraught woman, who has just identified her husband’s body. According to the coroner, the man died of shock and loss of blood; the police have not yet been able to find his arm…

The matter takes on an even greater urgency when Graham and Peterson learn that Thomas Lodge was out that morning with his two young sons, though their mother does not know where they were. Both boys are still missing…

The officers who found Lodge are questioned, but can suggest nowhere in the vicinity where a father might have taken his kids. Graham thinks to ask about arrests in the area—which leads the search to yet another hospital ward, this one containing a cheerfully rambunctious drunk who, between choruses of, “Gimme the booze!”, speaks of seeing “aeroplanes” and “ants” out of his hospital window…

Along with all its other virtues, Them! has one touch of distinct historical importance: it was the first film to make significant use of the distinctive setting offered by the drainage channels of the Los Angeles River: something which has since become an instantly identifiable cinematic landmark, and which is often found in other monster-movies, as a way of paying tribute to this one (two of the very best being Larry Cohen’s It’s Alive and Lewis Teague’s Alligator, both of which rework the underground climax of Them! for their own purposes).

An abandoned model-plane explains what the Lodge family were doing in the almost-dry channels. Gazing around, Graham and Peterson realise that, when the ants attacked, the two boys may have taken shelter in one of the many storm-sewers which open into the channel—and may still be alive.

On the other hand, if so, it is a case of the frying-pan into the fire, since the underground network of sewers offers a perfect pseudo-nest for the ants: one extending some 700 miles in total beneath the city…

There is a realisation that secrecy can no longer be maintained; but with the revelation of the truth becomes the enforcement of martial law.

(We get one of Them!’s few genuine disappointments here: the official broadcast is accompanied by various crowd scenes, amongst which – in Los Angeles! – we see precisely one person of colour…and he is a shoe-shine boy. Shame!)

A huge military force is put together, to undertake the daunting task of destroying the ants—and of finding the boys. One of those in charge thinks that both tasks cannot be successfully achieved; arguing they the boys are in all probability dead already, and that they cannot risk the ants escaping while they delay in order to search for them. “Are we supposed to jeopardise the lives of everyone in the city for two kids?” he adds impatiently.

“Why don’t you ask their mother that?” says Graham through his teeth; while Peterson adds, “Yeah, she’s right over there.”

Dr Harold has a compromise answer: that they can’t begin the full attack immediately anyway, not until they’re sure that no new queens have left the nest.

With each opening to the drain system covered by an army unit, the search is conducted by pairs of army jeeps connected by radio to each other. Within each pair, one jeep carries armed soldiers, the other an expert working a spot-light. One of the latter is Dr Pat—and guess what? – no-one says boo.

(In fact it’s she who tells Graham to, “Watch yourself.” He, meanwhile, after her display of courage and professional competence during the nest-search, has not again tried to tell her what to do.)

It is Peterson who, over both the noise of the engine and the rush of water, just catches an unusual sound. His jeep is stopped near a drain opening quite high up on a wall; he and his driver sit silent, listening to an irregular tapping sound.

The men radio to the other jeeps to halt, then consult a map. They learn that the conduit in question runs into an area still under construction. As Peterson dons a flamethrower, the driver reports to the surface command-post, asking for a check on whether there are lights at the construction site, and that they be switched on if so.

Peterson climbs up a wall ladder and crawls into the conduit. By the light of his lamp, he sees it open up into a rough, broad chamber. He calls out for the boys—and they answer him…

However, between Peterson and the boys are two ants. Seeing that, although terrified, they are temporarily safe in a narrow cavity in the far wall, Peterson shouts at the two to stay where they are, but promises them they’ll be rescued.

And then we get what is, in its unobtrusive way, perhaps my favourite moment in the whole film—at least in its implications:

Peterson (calling to his driver): “There’s two ants here, and I got a strong brood-odour—just like in the nest in New Mexico!”

Now—we didn’t hear it at the time, but Peterson could only have gotten that from Dr Pat…meaning that he has been listening to what she’s been telling them.

This may seem like a small thing, but if you’ve seen as many science-fiction films as I have, in which the powers-that-be call in the scientific experts and then pay no attention whatsoever to anything they say, you’ll know why that tiny moment makes my heart leap. That the scientist in question is a woman only makes it all the more satisfying.

Calling for troops to congregate at the nest-site, Peterson then lowers himself into the chamber, seeking an angle from which he can attack with the flamethrower without danger to the trapped children. He kills both ants, then rushes to get the boys to safety, lifting them one after the other into the opening of the conduit.

But just as he is lifting the second boy, another any charges into the chamber. Peterson stays focused on the child, pushing him into the conduit with one last effort—but in doing so, he is left without any time to defend himself. The ant’s mandibles close about his body…

This is a moment both rare and shocking: few films of this ilk succeed as well as Them! in making us care about their human characters, and fewer still contain any scene so genuinely upsetting as the heroic but cruel death of Ben Peterson.

Of course, there’s a secondary reason why we react like this, which is that it is impossible to warm up to this movie’s monsters. And this is how it should be: we’re not dealing here with a Harryhausen monster, who we want to hug and protect from the nasty humans trying to hurt it, but a relentless, faceless army. This is where the film’s insistence upon realism, a kind of realism anyway, pays off: they might cheat about the ants’ biology, but not their behaviour; there’s no attempt to infuse a personality into them, nor conversely to give them added, unnatural abilities or motives. They remain to the end simply ants.

But we shouldn’t infer from this that we are left to care about the humans just by default. We’re not: there’s some fine writing in the screenplay for Them!, and some fine acting in the film, too; and amongst a number of admirable performances, James Whitmore’s may be the best. Consequently, this is one of those rare films where I cry for the human and not the animal.

(Which is not to say I don’t flinch when the flamethrowers get going…)

The reinforcements arrive just too late to help Peterson. After killing the ant, Graham rushes to kneel by his mortality wounded friend; and with his last breath, Peterson assures him of the boys’ safety.

A violent battle then ensues between the soldiers and the in-rushing ants. Dr Harold arrives to put a stop to it, insisting that there must be no more use of explosives until the nest has been found and inspected.

As Graham leads a small squadron with guns forward, the tunnel suddenly caves in, trapping him alone on the other side of the downfall. Graham must fight off and evade more ants while the soldiers break open the obstruction. He escapes with his life but not without having his shoulder ripped open. However, the troops then break through and join the battle—and having killed or driven back the remaining ants, they find themselves on the edge of the brood-chamber. Inside, more winged queens sit ready to fly away.

Checking the scene, Dr Harold assures the others that no queens have escaped, and the final assault begins…

But humanity’s triumph – if you can call it that – is short-lived: as he looks on, Graham wonders about all the other atomic tests?

Dr Harold: “When man entered the atomic age, he opened a door into a new world. What we will eventually find in that new world, nobody can predict…”

“Don’t talk to me about ants!” Jack Warner notoriously snarled while Them! was still in production. He changed his tune once the film was released: this low-budget science-fiction drama became one of the top-grossing films of 1954 across the board, and among the top two or three released by Warners that year. In fact, some charts (according to how the figures were calculated) have it as the most profitable Warners film of 1954.

Not only did the public eat up Them!, it was generally well-received by the critics, too; and time has only enhanced its reputation. It may not be the first film you think of when the subject of the great science-fiction films of the 1950s comes up – let’s face it, the competition is pretty stiff – but it more than holds its own against the rest.

Them! is one of those films that manages to stay fresh over multiple viewings. Some of this is due to the leanness of its storyline, the absence of any diversions or padding; some to the seriousness of its execution; and some to the quietly effective acting, which puts flesh on fairly cliché character outlines. I’ve praised the main cast already, but I should mention some of those in support, too, including a few significant bit-players.

Most prominently, the unfortunate Alan Crotty (whose government has, we hope, decided that he’s “well” by now) is played by Fess Parker, a performance that won him the TV role of Davy Crockett; while the cheerful drunk is played by Olin Howlin, who four years later would find screen immortality as the first victim of The Blob.

But it is those with sharp eyes who will have the most fun here: among the supporting cast we find William Schallert as the ambulance attendant; Ann Doran as the child psychologist; Dub Taylor as the night-watchman; Dick Wessel as the railway detective; and last but definitely not least, as the army sergeant who delivers the message about Crotty’s strange experience—a baby-faced Leonard Nimoy!

As science fiction, Them! is important on two fronts. As the very first “big bug” film, it was responsible for unleashing an infestation of copyists, not one of which came within touching distance of its qualities, dumb fun though a number of them may be. Like everything else in this film, the ants were taken quite seriously by their creators, and it shows on screen. Biological reality is ignored only where it must be, making the ants a believable and tangible threat—even though the worst of what they do must be kept off-screen. (The bone-pile moment is pretty shocking, all the same.)

In that respect—we can’t help noticing here that although Pat Medford gets away with describing the crisis as, “A scientist’s dream come true”, at no point does either she or her father suggest anything less than the complete destruction of the ants. Far from “saving one for science”, they don’t even seem to want to preserve any dead specimens for later study; though I suppose there are plenty that could be retrieved from the nest in New Mexico, once the situation has been resolved. In this, Them! was again followed by Alligator, whose scientist also takes the prosaic view that the giant ’gator isn’t special, it’s just big.

But it is as an atomic-scare film that we need to stop and consider what Them! is actually saying.

In some respects it is disturbing to find, in Them!, science and the military so comfortably hand-in-glove—particularly in a film about cleaning up the atomic bomb’s mess. We might also feel that the film’s threat is, in the end, identified, contained and neutralised a little too easily—with the implication that the American military is capable of neutralising all such threats. Of course, at the time everyone may well have believed this: the lessons of Vietnam were still a decade away, and two decades away from being learned.

However— The working relationship that develops between the main characters does make a refreshing change from the science versus the military plot established by The Thing, and so frequently (and often thoughtlessly) reproduced elsewhere. And even here, Them! does things a little differently. One of the most striking things about this film that in any given situation, whoever is best qualified to deal with it is always in charge—which sometimes gives us the military taking orders from the scientists. It is taken for granted that teamwork and cooperation are the best way of dealing with the crisis, with each person’s expertise coming to the fore in turn, and everyone pitching in wherever he or she is needed. (When Graham is trapped by the collapsing tunnel, General O’Brien rushes to help with the digging). Conversely, almost startling by their absence are the power-plays, head-buttings and tantrums usually associated with this sort of subplot, as a way of creating (artificial) drama.

(Note to self: re-watch The Swarm.)

But despite the film’s humanism, despite too the comprehensive manner in which the threat is dealt with, there is as noted an ambiguous air to the film’s politics which prevents us from taking all this at face value. In particular, there are a few too many casual violations of civil rights along the way by those in authority. This is for “our own good”, of course – it always is – and to avoid the panic the Higher-Ups seem to feel is otherwise inevitable. This evident lack of faith of the government in its people is curious when set against the mutual reliance of those on the front lines. It feels as if a distinction is being drawn between those who make wars and those who fight them.

And perhaps we should consider all this in light of the fact that Them! is the first American film to really place the possible consequences of “the bomb” front and centre. Sure, just the year before, it was an atomic test that woke up The Beast From 20,000 Fathoms; but in that film, as in so many to follow, that was really just an excuse: rather like calling a scientist “mad”, once you’d said “radiation” in a film of the 1950s, you could get away with anything.

But Them! isn’t playing that game; it isn’t playing a game at all. Instead it deals explicitly with the genie out of the bottle, arguing that what started at White Sands did not simply stop at Hiroshima and Nagasaki; that such forces, once unleashed, have a tendency to take on a dangerous momentum of their own; including, perhaps, rebounding against those who set them in motion in the first place.

Want a second opinion of Them!? Visit 1000 Misspent Hours – And Counting.

♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦

This review is for Part 3 of the B-Masters’ 20th anniversary celebration!

We’ll never have another year like 1954.

Somehow, the fact that you’d never reviewed this escaped me. Maybe subconsciously it just felt like you had, because…well, OBVIOUSLY you had. Right?

I was a bit older than you when I first saw it, but I’d managed to avoid knowing the secret of “Them!” and so I got a similar moment upon hearing about the formic acid. It took being a bit older to get the significance of the brood-odor comment, but when I first picked it up…well, I’m sure my grin didn’t surpass yours, but it was still pretty big nonetheless. Dr. Pat may be my favorite of the female leads in this genre, with the possible exception of any played by *sigh* Mara Corday.

Really enjoyed this review. This is one of those rare treats, where you review a movie I feel confident that I know as well as you do — Gojira being the obvious example — by virtue of my love for it (and resultant multiple viewings of it). Thus, I can simply read along, loving the fact that you just get it.

I feel like there’s something I should tell you…something I haven’t told you lately…

“Dr Harold: “We may be witnesses to a biblical prophecy come true: ‘And there shall be destruction and darkness come upon creation, and the beasts shall reign over the earth’…”

Yeah. We wish.”

…………………….huh. Just can’t seem to think of what it is I should be telling you.

😉

LikeLike

1954, huh?? 😉

I know, it’s ridiculous that I haven’t gotten to this before; but then I have an entire long list of ridiculous, sigh…

Hmm…yes, but…do you admire Mara for her science or just for her pyjamas??

Ah, well…I’m sure it will come back to you sooner or later… 😀

LikeLike

That was just about perfect, wasn’t it (the 1954 thing)?

Can’t I admire Mara for both?

Yes, I’m sure it will… 🙂

LikeLike

So, Dr. Harold. You call yourself a scientist? The common rules of giant bug movies apply here, namely that the mass of a giant insect can’t be supported by the muscles by the Square-Cube Law and somehow stridulation always confuses the filmmakers into thinking insects have vocal chords. (Although Them! sounds very stridulaty, real word.) But since I have a BS in entomology and this movie is partially to blame for that (as well as praying mantis oothecae which is another story when Alyssa gets around to The Deadly Mantis) I am allowed to pick on this.

When Dr. Pat is first meeting our giant desert friend and the guys come to her aid, good Dr. H clearly says, “Get the other antennae!” Which is the plural of antenna and if one is gone that leaves just a singular antenna to be machine gunned off. However, even more suspect to Dr. H’s credibility is his repetition and addition. “Get the other antennae! HE’S helpless without them.

Even with the exposition of explaining to the laymen that ant drones go on mating flights then die off and they’re only interested in the queens escaping to make new nests, a lone wingless ant is going to be a SHE.

LikeLike

It’s funny how people think that ants have super strength, when it’s actually just that natural laws don’t scale the way people expect them to.

LikeLike

Normal ant strength is one of the things dealt with during the Washington lecture. If we’re allowed to multiply up flight distance, we can certainly extrapolate strength. 🙂

LikeLike

I’m watching “Them!’ on Turner Classic Movies as I type. The first ant encounter was about ten minutes ago. Gwenn clearly says “antennA” when directing Whitmore and Arness to shoot the remaining feeler.

LikeLike

I had put the DVD away and had to go and dig it out again, but—Dennis is correct: Dr Harold says at first, “Get the antennae! Get the antennae!” When Peterson has taken out one of them he then shouts at Graham, “Get the other antenna!”

He does says “he’s”, though. Perhaps he was afraid that if he told Graham the ant was a girl, he wouldn’t want to shoot it. 😀

(“Its” should have been the pronoun of choice, I think.)

The film doesn’t get into how the ants are making their noise, so those of us who feel inclined can view it as a detail done correctly.

LikeLike

Them! really is an extraordinarily good film. I first saw it on TV many years ago when I was… 11, maybe? I didn’t see it again until last year, only to find that it’s even better than I remembered it being. I remembered it as a really good 1950s monster movie; I didn’t realize until I saw it again that it’s actually a really good MOVIE, period. Definitely the all-time best giant insect movie ever made (sorry, Mothra, you know I love you, but…)

LikeLike

Yes, sometimes you only remember “the good bits” and therefore remember a movie as better than it is, but Them! is just flat-out good movie-making.

Mothra, who gets “Well, she didn’t mean to stomp Tokyo” and therefore gets away with it… 😀

LikeLike

The young Lyz in my head says: “If ants cannot grow to be eight feet long and take over the world… we shall have to make better ants!”

LikeLiked by 1 person

Not better; just better organised. 😀

LikeLiked by 1 person

I agree but I will admit that as a kid seeing this film, I did think the baby queens at the end were cute.

LikeLike

Yes, they’re a little too cute for what’s done to them.

LikeLike

I’m very glad that Them! was, through accidents of availability, just about the last of the classic Giant Bug films I ran into– I can only imagine the disappointment of people who had this in their mind when they saw The Deadly Mantis. One might almost believe the concept of a golden age, a halcyon past in which the nigh-Platonic ideal was laid down and of which subsequent eras are only a clumsy and imperfect attempt at copying. It would be a hell of a slope, though, given that Beginning of the End came out only three years later.

LikeLike

Same old problem: most of the copyists thought that providing a giant bug was enough.

The Beginning Of The End* at least has a plot, even if it’s a really dumb one. 😀

(*It only occurred to me on this viewing of Them! where they got their title from…)

LikeLiked by 1 person

The Beginning of the End also tried made their monsters a mystery during its original publicity campaign. Oh the disappointment!

LikeLike

I have a special fondness for this film because of a weird reason.

I was at Magic Mountain (now Six Flags) and while waiting in line for a ride the operator asked some trivia questions including:

“What were “them”?”

I replied: “Ants! Giant Ants!” and won a large rubbery bug!

I won’t comment about how far away White Sands is from the Trinity site.

LikeLike

WHOO!! – so jealous!

Yeah, but—even if they knew, would they have been allowed to say?

LikeLike

Sure, that was very public knowledge at the time.

LikeLike

By coincidence I just went to the national nuclear testing museum, and there was no testing near White Sands. Most of it was north of Las Vegas, but that did not get going until after 1954.

They did mention “Them” as part of the popular culture for 1954.

LikeLike

That’s interesting! So is White Sands something the movies made up, another sort of facility whose function was misunderstood, or a name sold to the public to divert them from the truth?

LikeLike

White sands missile range – not the national monument – was a pretty well known test area from the mid forties. Wikipedia does say that trinity was near the north boundary of the range

LikeLike

For those with U.S. Comcast Cable –

Tomorrow, Friday 9/6/2019

Insect theme day lineup

12:30pm – Cosmic Monters

1:45pm – The Wasp Woman

3:00pm – Highly Dangerous starring Margaret Lockwood as an entomologist

4:30pm – Them!

6:15pm – The Fly

LikeLike

I’m surprised you didn’t mention the brief scene where they pick up a woman and it’s implied she’s sleeping with a man…they’re not married. Maybe I’m remembering wrong, she claimed they were friends and that he was ill. It was towards the later part of the movie and out of the desert. I kind of liked that as a strangely little ‘real’ moment of the 50s. Y’know for a long time there was this wholesome notion of the 50s being squeaky clean. Or maybe I’m remembering this wrong. Hey I don’t care if she was checking up on him or they were in a relationship or what.

LikeLike

No, you’re remembering perfectly correctly: the woman is one of the four people arrested in the same general area and at the same general time as the attack on the Lodge family, three drunks and her. She’s busted for speeding through a red light rushing to get home after “spending the night with a sick friend”…who’s married.

It’s another tiny breakthrough moment of the kind I discuss at (much more) length re: The Naked Jungle, made the same year.

LikeLike

That whole sequence is great, I love the two guys discussing the merits of the formal social life. Being that witty (and sarcastic) while recovering from a bender is impressive.

And from a dramatic perspective, it nicely sets things up for the interview with the mom and the implied horror (which, in another nice touch, is strengthened by the fact that the movie has already established that kids aren’t automatically safe).

It’s just such a well done movie, I often watch parts of it just to appreciate the craftsmanship.

LikeLike

Really great review – thanks for covering this film! I’ve always had a fondness for THEM! I was lucky enough to catch it on Friday Night Frights when I was a kid, and somehow had no idea what it was about, so the whole ‘mystery’ aspect took me by surprise, and the reveal of the ants totally blew my little mind (which was entirely capable of suspending disbelief at the big floppy fuzzy antennae). I think it’s interesting how many parallels there are between the plot of THEM! and ALIENS (the little girl as surviving witness, the flamethrowers in the egg chamber, strong female protagonist, etc.). Probably not enough to write a paper on, but interesting.

LikeLike

Thank you! 🙂

You’re quite right: while writing this I started to get into how Aliens owes as much to Them! as Alien does to It! The Terror From Beyond Space, but it grew into too much of a detour (if not quite a paper).

LikeLike

Wonderful to read one of your reviews again, Lyz, especially about a movie that’s been a favourite ever since I saw it as a happily terrified kid. I’ve always believed that ‘Them!’ inspired a large amount of the storyline of ‘Aliens’, even down to Newt’s plastic doll. I suspect that the original creator of the Alien must have also read the pulp novel ‘The Furies’, which has wasps laying their eggs in the bodies of living, immobilised humans.

LikeLike

Several years ago I was at the Shedd Aquarium in Chicago, where suddenly, I heard the call of the giant ants from THEM!. I traced this to a display on Amazonian tree frogs, where you could push a button and hear a chorus of them chirp and croak. Here, yours truly, kept gleefully pushing the button for five solid minutes simulating a giant ant attack, cackling the whole time. And it would most probably have lasted a lot longer but there were also otters and belugas to go gawk at.

LikeLike

Years ago I drove up to Missouri. A storm had blown through during the day and knocked power out. So, when I got to my destination that night, it was damn near pitch black. And then, as I was unloading the car, I heard what sounded exactly like Them! I’m guessing it was the local cicadas; never did find out for certain. All I know is I spent a few moments intensely scanning the darkness, ready to run like hell, before logic reasserted itself.

If you check the Wikipedia page for “cicada,” scroll down and listen to the cicada sample from Greece; that’s pretty much exactly what I heard.

LikeLike

Oh, brilliant!

1954 again: how freaky that while Ifukube Akira was rubbing a leather glove over fiddle-strings, Francis Scheid was out recording tree-frogs. 😀

LikeLike

before logic reasserted itself

Before what did what!?

Feh! – what a dull way to live… 😀

LikeLike

At least I had a few moments of ridiculous fear, instead of simply thinking, “Huh. Sounds like Them!” and going about my business, not once letting my imagination run wild. I was actually kind of happy I was capable of such flights of fancy in my advanced age, and here you are dumping all over it.

Madam, you wound me.

LikeLike

No, merely confessing that I have never lost the capacity for ridiculous fear. 😀

LikeLike

When I was a kid, the local farmer’s market had an alarm / siren / thing that sounded oddly like the wailing of the ants. My parents would leave my brothers and I in the car while they shopped, and we would cower whenever that went off.

Now, of course, I’d love to have one of those myself.

LikeLike

I’d forgotten about them until I read your comment, but we used to have tons of cicadas every summer about this time. They were very, very loud. They were about 3 inches long and were EVERYWHERE. I’m glad I didn’t remember this movie then.

I never heard how it was to be pronounced – is it ciCAYda, or CIcahda?

LikeLike

In the UK (which doesn’t help you), ciCAHda.

LikeLike

sih-KAY-da.

LikeLike

dawn: We had cicadas where I grew up, but not enough that they were a constant presence. We did have one tree they liked to molt on; any time they came up, it’d have at least half a dozen shells on it. Here in Texas…well, we have a wasp that’s specialized for hunting them, so that tells you how many we have, even in the big urban areas. Luckily their noise doesn’t bother me a bit (although I wish they did the “Them!” screech).

I’ve always heard it pronounced the way Alaric does.

LikeLike

IT’S THEM!

I heard them tonight. I was so glad to hear them again. This is late in the year for them, they used to come about a month earlier.

But of course it couldn’t be climate change. Just because we’ve had more 100+ deg days this year than ever (Willcox AZ, 4k alt).

(sorry, is that opening a big can of worms for discussion?)

LikeLike

Not around here it’s not.

We were in danger of losing our cicadas to drought a few years ago: the ground was go hard and dry that they couldn’t burrow, and so there were years when no eggs were laid, and others when there was nothing to hatch. They are now recovering (we’re doing flood rather than drought now, at least on the coast), but there’s been a shift in the relative populations. We used to predominantly get ‘Greengrocers’, but now its forever since I’ve seen anything but a ‘Black Prince’.

We still don’t have anything like the ubiquitous choruses that we used to get, to the point where you could set your evening clock by them. Now it’s more a matter of them occupying individual tress, and you reacting *if* you hear them. I haven’t even seen an empty case since I was last walking in the National Park.

Si-CAH-da, with a very short first syllable.

LikeLike

So, today I learned Australia has cicada killers, too. I imagine they’re similar in size to ours (4-5 cm).

I also learned the cicadas here are called scissor grinders. Considering their call (which you can easily find online), it makes sense. I love it; it’s like an electronic siren that then does this wonderful buzzy decrescendo that drops in pitch. They’re also what I heard growing up (they actually range that far north, sure enough).

Lyzzy: I wouldn’t expect you to know this, but as far as ridiculous fear…do you know when the last time I wiped a foggy bathroom mirror clear was? 😀

*adds “walk in National Park with Lyz” to itinerary for (someday) visit to Australia*

LikeLike

A great review, good attention to both cinematic and scientific details, as usual.

LikeLike

Thank you, much appreciated!

LikeLike

Watched the clip on YouTube and reality trumps faulty memory. He perfectly says multiple antennae when there are two and switched to singular when the one is disabled

LikeLike

Yeah, noted above. You’re quite right above the ‘he’s’ slip though.

LikeLike

Given the stress of the situation (as in, it’s one thing to be theorizing about an eight-foot-long ant, it’s quite another to see one menacing your daughter), I think the doctor could be forgiven the pronoun gender slip.

LikeLike

But…but…but…he’s a SCIENTIST!!

LikeLike

Indeed, and that sequence makes me chuckle everytime. “Shoot the antennae!” They shoot one antenna then stop. “Shoot the other antenna!” It could just be me, but I swear there is an unstated “you idiots” at that point.

LikeLike

😀

That’s not fair: he’s talking to Peterson in the first place, then shouting at Graham who wouldn’t have heard him over the wind.