“You’re gunna need a bigger boat…”

Director: Steven Spielberg

Starring: Roy Scheider, Richard Dreyfuss, Robert Shaw, Lorraine Gary, Murray Hamilton, Jeffrey Kramer, Carl Gottlieb, Lee Fierro, Jeffrey Voorhees, Chris Rebello, Jay Mello, Susan Backlinie, Robert Nevin

Screenplay: Peter Benchley, Carl Gottlieb and Steven Spielberg (uncredited), based upon the novel by Peter Benchley

Synopsis: During an all-night beach party on Amity Island, Chrissie Watkins (Susan Backlinie) goes for a swim and is dragged to her death by something in the water… The next morning, Amity’s police chief, ex-New Yorker Martin Brody (Roy Scheider), goes to the beach with the young man who reported her missing. The two hurry along the sands upon hearing a frantic signal from Deputy Hendricks (Jeffrey Kramer), who has found washed up on shore what little remains of Chrissie… When the medical examiner reports the cause of death as ‘shark attack’, Brody orders the beaches closed. Learning that a group of boy scouts are scheduled to do a mile swim that morning, the sheriff then rushes to the local ferry terminal, hoping to head the boys off. On the boat, he is cornered by Amity Mayor Larry Vaughan (Murray Hamilton), local newspaper editor, Harry Meadows (Carl Gottlieb), and the medical examiner (Robert Nevin); Vaughan tries to persuade Brody that his order to close the beaches was premature, an overreaction. When Brody argues that it is the correct response to a fatal shark attack, Vaughan presses the medical examiner to concede that he may have made a mistake in his original conclusions, and that Chrissie’s injuries may have been inflicted by a propeller. Reluctantly, Brody gives in, and life in Amity goes on as usual—until a boy named Alex Kintner (Jeffrey Voorhees) is bloodily killed in a daytime shark attack witnessed by dozens of beach-goers, including Brody himself. At a town meeting, local business-people continue to resist any measure that will impact the summer tourist trade, and react with dismay to the bounty placed on the shark by the devastated Mrs Kintner (Lee Fierro), which is advertising the shark’s presence far and wide. Brody explains to the gathering that they will be hiring extra deputies and shark-spotters to help deal with the situation. However, in the face of relentless questioning, he is forced to admit that he also intends to close the beaches. The crowd’s angry reaction drowns out Brody’s announcement that an expert from the Oceanographic Institute is on his way to Amity. The protestors are silenced, however, when a local fisherman called Quint (Robert Shaw) offers to catch and kill the shark for a flat fee of ten thousand dollars. His offer is not accepted, but before long Amity is flooded with fisherman, both professional and amateur, all hoping to catch the shark and secure the bounty offered by Mrs Kintner. Among the arrivals is Matt Hooper (Richard Dreyfuss), the marine biologist from the Oceanographic Institute, who is appalled by the reckless behaviour of those venturing out onto the water. Hooper introduces himself to Brody, who invites him to examine Chrissie Watkins’ remains. Hooper confirms that she died from a shark attack, and angrily denounces the medical examiner. Meanwhile, it seems that the fishermen have succeeded: Brody and Hooper rush back to the docks to find that a large tiger shark has been killed. As the townspeople, including the relieved Brody, celebrate, Hooper examines the animal—and comes away almost certain that it is not the shark that killed Chrissie. An argument between himself, Brody and Larry Vaughan is interrupted by the arrival of the furious and grief-stricken Mrs Kintner, who now knows of the first fatal attack, and tells Brody flatly that he is responsible for her son’s death. That night, as Brody drowns his sorrows, Hooper makes a second effort to convince him that they must examine the contents of the tiger shark’s stomach before the animal is disposed of. The two men cut the shark open, and so confirm their worst fears: the killer shark, a much larger animal, is still out there…

Comments: There was a time, getting on for fifty years ago, when it was assumed by the producers and distributors of motion pictures that no-one really wanted to spend a summer day inside, sitting in the dark and watching a movie. Consequently, the summer months were generally used as a dumping-ground for those productions of which little was expected in terms of financial performance, or which might appeal only to a niche audience.

All that changed, however, in the American summer of 1975, when a single film altered forever the way that movies were made and marketed, and single-handedly created the concept of “the summer blockbuster”.

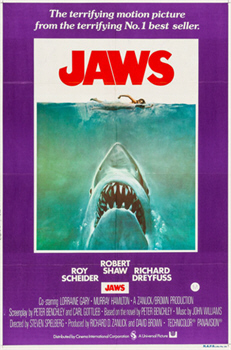

(That’s the Australian one in the middle; I don’t know why we went with purple.)

In fact, that particular film did more: it created in the process the perfect feedback loop, by frightening the summer crowds away from the beaches—and back into the cinemas…

While we might deplore some of the consequences of its success, including its part in the development of a “bigger is better” mindset focused upon opening-weekend takes, saturation advertising and an emphasis on the sizzle rather than the steak, there is little to criticise in Jaws itself. The film is a brilliant exercise in the blending of genres, and an object lesson in “layering”: an adventure written in broad strokes, but one supported by thoughtful characterisations and first-class performances, and with an attention to texture and detail that adds immeasurably to the richness of the finished production.

Of course—the film had no right to turn out like that. As we now know, Jaws is one of those films that somehow succeeded in spite of itself, second only to Casablanca in creating brilliance out of chaos. (Second because, as we shall see, Jaws does not always quite succeed in papering over its cracks.) In fact, the more you know about it, the more you have to wonder how anything went right.

Even before production began on Jaws, some significant chances were taken, with an inexperienced director assigned to the self-evidently difficult shoot, and pre-production cut short in order to take advantage of (what were expected to be) appropriate weather conditions. Then, almost from the first day of production proper, things went wrong. The short preparation time meant that shooting started before the screenplay was finished; it ended up being written, and rewritten, on the fly, with scenes constructed only the night before they were filmed and the cast given minimal time to prepare. The good weather evaporated almost immediately, to be replaced by wind and rain that hampered shooting and made matching of the footage next to impossible.

Furthermore, the combination of rain and sea-water resulted in the production being plagued by mechanical failures—most seriously with respect to the animatronic sharks via which the film’s menace was intended to be actualised.

The consequences of all this were unavoidable: the shooting schedule blew out, and so did the budget, with a nervous Universal finally spending almost ten million dollars more than intended upon “a summer film about a shark”.

The studio needn’t have worried: Jaws went on to make a staggering $260 million in its domestic market alone, making it America’s top-grossing film of 1975; it would go on to make $470 million worldwide. Adjusted for inflation, Jaws is currently ranked #7 on the list of highest-grossing films of all time.

But the money only tells a part of the story—and not the most important part. Jaws is a film that crosses boundaries in a manner that only a handful of truly great films succeed in doing: an adventure film, but one whose strength lies in its characters and their dialogue; a male-focused action film that appeals to most ages and both sexes; a thriller that blends suspense with touches of genuine humour; a horror film for those who usually wouldn’t be caught dead watching one.

And a two-hour film about hunting and killing a shark that can make a shark-lover, love it.

As you would appreciate—I have something of a contentious relationship with Jaws. I can’t exactly call it a love-hate relationship, because I certainly don’t hate the film; on the contrary; but I do hate what it wrought.

I’ll do my best here to stay focused and treat Jaws simply as a film, and to remind myself it was built around what people thought they knew at the time, but—well, apologies in advance if I wander off-topic.

Jaws is a movie that sets its tone from the opening frames of its credits: an ominously prowling underwater camera, and that still more ominous music…

John Williams’ score for Star Wars is usually credited with reviving the dying art of full orchestral movie scores, but it started here, with his less flashy but no less indelible work for Jaws. Those shivery chords are not merely a perfect complement for the film’s central menace, but so very effective that – as became more and more necessary as things went wrong during production – they are likewise a perfect replacement for it: the music alone is enough to put the viewer into a state of full tension.

That said, I have to admit that I find some of Williams’ other work on this film less successful. The “seafaring” themes that accompany the scenes involving the Orca are a bit much for my taste; or, perhaps more correctly, a bit too light-hearted in tone for the material they support.

On the other hand, this a film that really knows how and when to use its music—and critically, when not to use it at all. Too many films these days overuse their score, pouring music into almost every scene so that it loses its effectiveness. Jaws, conversely, is a brilliant exponent of silence; of letting the ocean speak for itself. Long stretches of this film have no accompaniment at all. That creeping music, when it re-emerges, therefore has twice the impact.

Jaws opens upon a night-time beach party: young adults play music, drink beer, smoke pot, and canoodle; one young man catches the eye of a young woman, sitting somewhat isolated from the party proper. She smiles at him invitingly, and he crosses to her side.

Almost instantly, the young woman leaps to her feet and sprints off. The young man accepts that tacit invitation, too, and runs after her; she calls over her shoulder that they are going swimming.

But it turns out that the young man is somewhat the worst for wear after his night’s indulgences, and he is unable to keep up with his companion—even when she adds to her general invitation a more specific one of stripping off her clothes as she runs. Naked, she sprints across the beach and plunges into the water, striking out for a buoy some distance from the land. The young man, meanwhile, gives up the chase and collapses onto the sand, vainly fighting his state of intoxication.

The young woman pauses in her swim, floating effortlessly, at home in the water; she dives, and somersaults, one leg raised gracefully above the surface like a sail—or a fin. She looks back, calling to the young man, but there is no response from him.

Suddenly, as the young woman treads water, something jerks her beneath the surface. Fear grips her: a fear that turns to mortal terror as she is dragged back and forth, pulled again and again beneath the water. She makes a desperate grab at the buoy and for a few moments clings to this last poor defence, as her screams cut through the night; she is then dragged under one last time…

Few films provide so unforgettable an opening gambit as Jaws. The scene is exquisitely constructed: unforgettable in its switch from serene beauty to brutal violence; terrifying in its implications.

One thing, however, that I don’t think has ever received enough credit is the performance of Susan Backlinie. She had done some acting when she was cast, but she was predominantly a stuntwoman and an animal trainer, and her main qualifications for the role were her ability and her willingness to work in the water at night and to go through the difficult and potentially dangerous harness-work necessary to get the scene shot (and also, of course, to get naked and be photographed so).

Yet it is her acting that we remember; the utter terror she conveys, the human tragedy of this random, violent death. Not much happens by way of “action” over the next phase of Jaws, as the film takes its time in introducing its characters and setting up its narrative; but the shadow thrown by this opening sequence is long and dark, and Backlinie’s contribution is its most significant component.

We should note that the stories of Backlinie being seriously injured during the filming of this scene are untrue. It is true that Spielberg didn’t warn her when the jerking-around was going to begin, so those first, startled reactions are genuine; but beyond that, the performance is all Backlinie’s own. The suggestion that she was really injured, really screaming in pain, is in its way a compliment; but it also takes away from the power of her performance.

The following morning dawns bright and sunny across the island community of Amity, including directly into the bedroom of former New Yorker, now sheriff of Amity, Martin Brody; his equally sleepy wife, Ellen, reminds him that they bought the house in the fall; now it is summer.

One of the many almost immeasurable improvements made in adapting Peter Benchley’s novel for the screen was the decision to make the Brody family – Martin, Ellen, and their two boys, Michael and Sean – the narrative’s anchor. This is not to say that Steven Spielberg pushes them at the viewer—as, alas, he might have done at a later point in his career. Rather, he simply foregrounds these people and allows their quiet normality (as opposed to the tiresome marital difficulties that drive their narrative in the novel) to give us a measure for much of what happens later. And while the performances from Chris Rebello and Jay Mello as the boys are adequate, the interplay of Roy Scheider and Lorraine Gary, as a long-married couple at perfect ease with one another, is remarkable in its warm naturalness.

Both Brodys are then shaken out of their remaining sleepiness, Ellen when she is called upon to clean and dress a bloody cut across the hand of eldest son, Michael – which she does with the matter-of-factness of long experience – Martin when he receives a phone-call. His side of the conversation alerts us to a report of a missing person, a possible case of drowning. He promises to be on the scene in about twenty minutes.

Once there, Brody questions the young man, Tom, who rather shamefacedly admits he’s not sure what happened; although the discovery at the scene of Chrissie’s clothes and bag suggest the worst. A whistle blows frantically in the distance. The two run towards the sound, and find Brody’s deputy, Hendricks, slumped upon the sand, looking shaken and sick. Nearby is Chrissie’s body; what’s left of it.

This is the film’s first real gross-out moment, not so much the hand jutting from the sand but the crabs crawling all over it. A fake arm was constructed for this shot but in the light of day it looked too fake, so they ended up burying a crewmember in the sand instead. The fake arm shows up later in the morgue scene, however.

It’s too early even for the Amity Police Department, so when Brody’s secretary, Polly, arrives, she finds her boss already hard at work at his typewriter, barely lending an ear to her report of out-of-control young karate students as he writes up his report. (Not well: “CORNERS OFFICE”?) The phone rings; and in response to the voice at the other end of the line, Brody adds a cause of death to his report: SHARK ATTACK.

Learning that there are no ‘beach closed’ signs in existence, Brody rushes out to buy the necessary items to make them, running a gauntlet of citizens with comparatively minor grievances and the preparations for Amity’s 4th of July celebrations.

On his way back he encounters Hendricks, who tells him that a group of Boy Scouts are out on the water. They exchange jobs, Hendricks being sent back to the station to construct the signs, and Brody commandeering the departmental truck to go and call the boys back in.

Brody drives off, just missing a summons from Amity’s mayor, Larry Vaughan. It is Hendricks who tells Vaughan that there has been a fatal shark attack at South Beach…

At Avril Bay, Brody has just stepped onto the ferry when a car follows him onboard: it disgorges Vaughan, Harry Meadows, the local newspaper editor, and the town doctor—who doubles as its “medical investigator”.

Cornering Brody against the railings, Vaughan and Meadows point out the damage that will be done to Amity, a community dependent upon summer tourist dollars, should the beaches be closed; debating, in fact, whether Brody even has the authority to close them. As the sheriff hesitates, the two ramp up the pressure, arguing that there has never been anything like a shark attack in the Amity waters, and that maybe Brody is rushing into things: it is his first summer, after all…

Brody can only appeal to the doctor, but finds no help there: with Vaughan’s helpful prompting, the doctor now concludes that he probably made a mistake, and that the injuries to Chrissie’s body could have been caused by a propeller. Such “boating accidents” have occurred before:

Vaughan: “It’s all psychological. You yell, ‘Barracuda!’, and everybody says, ‘Huh? What?’ You yell, ‘Shark!’…and we’ve got a panic on our hands on the 4th of July…”

And so the beaches stay open…

And the people of Amity make the most of it. Many of them lie in the sun, talking and laughing. Others swim and horse around. A man plays with his dog, throwing a stick into the water. A boy begs his mother for a few more minutes on his inflatable raft.

The Brodys are among those present. Ellen is chatting with some locals, learning to her laughing dismay from one of them, hotel owner Mrs Taft, that she and her husband will never be “Islanders”. (Earlier, the boy who reported Chrissie missing told Brody casually that, though he lives in Hartford and his parents in Greenwich, they’re all still Islanders, because they were born there.) We see that Brody is not paying attention to the conversation: his gaze is fixed on the water…

Throughout this scene, the camera wanders around, picking out this person and then that one in an increasingly unnerving fashion. Our first sense of something really wrong is the owner of the dog standing at the water’s edge, calling unavailingly for his pet. (Spielberg foregrounds Sean Brody in this shot, reminding us what his father has personally at stake.) Then the camera drops below the water—and the music starts…

Alex Kintner’s death remains as confronting and upsetting today as it ever was, both in its immediate bloody violence and its profoundly unjust randomness. It sparks a panicked rush in both directions, with those on the beach rushing towards the tragedy, and those in the water scrambling to get out. Terrified survivors run to their family and friends, and reassuring hugs are exchanged. Parents are reunited with their children, including the Brodys with theirs.

And at last, only Mrs Kintner stands alone, as a ripped and blood-stained raft nudges the shore…

There is one more critical point in this scene. The viewer has only just been made aware of Brody’s water-phobia when the attack occurs, via a rather contemptuous remark from an elderly local. Brody is among the crowd that rushes to the water’s edge in the wake of the attack—but only to the edge: he stays there even though Michael is in the water; at this stage, even his fear for his son can’t push him any further. It is Ellen who plunges in to help other people out—though not actually Michael, who we see assisting a child younger than himself. The point is not emphasised, but in retrospect it serves as a measure of Brody’s problem.

The death of Alex Kintner, and the placing by the devastated Mrs Kintner of a bounty on the shark, prompts a meeting between Amity’s business community and the town council—headed by Mayor Vaughan.

When Jaws was released in the American summer of 1975, in the wake of the Watergate scandal, there was an understandable tendency to read Larry Vaughan as a corrupt and venal politician intent upon instituting a cover-up; and amongst the welter of Jaws rip-offs that have since seen the light of day, not a few have included a Vaughan-figure who helps make the situation worse by refusing to close—whatever it might be in context, from a national park to the ski slopes. In fact, so deeply ingrained is this by-now cliché in our collective movie-consciousness, many of these productions don’t even bother to give a reason why the whatever should not be closed.

However, the passing years have seen various efforts to rehabilitate the reputation of Larry Vaughan, or at least to see him less simplistically. The chief argument made in his favour is that in refusing to close the beaches, he is simply doing what he was elected to do, and representing the interests of his constituents. The town-meeting scene leaves us in absolutely no doubt that, despite the death of Alex Kintner and the persisting danger, the local business leaders want the beaches kept open.

And that’s true, as far as it goes; but it doesn’t go far enough: while Vaughan no doubt has a financial responsibility here, and a very big one in this “summer town”, he has a greater one with respect to public safety. His refusal to have the beaches closed, under the circumstances, amounts to reckless endangerment—not of the townspeople, who know the truth, but of the tourists whose money they rely upon.

But it isn’t what Vaughan does but the way he goes about it that finally condemns him. Upon his first appearance, when he catches up with Brody on the ferry, he pursues a cynical but shrewd and effective policy of exploiting the sheriff’s newness in Amity, and his uncertainty about the limits of his authority, to get him to back down about closing the beaches. Furthermore, the demeanour of the medical examiner, as he changes his cause-of-death ruling from “shark attack” to “boating accident”, makes it perfectly clear that he has been got at, and pressured into what amounts to the falsification of medical records.

Worst of all, though, is Vaughan’s attitude towards Chrissie herself, who he dismisses as, “A summer girl”—as if that somehow makes her life of less value, her death of less importance.

(His use of that phrase introduces a note of shared culpability: earlier we hear one of the townspeople using the contemptuous expression, “Summer ginks.”)

As for the town meeting— There Vaughan shows himself a perfect politician, taking the temperature of the gathering before he commits himself to anything, and hanging Brody out to dry when it comes to telling the business leaders things they don’t want to hear: making him announce the closing of the beaches, and undermining him with a hasty, “Only twenty-four hours!” when he is howled down.

The meeting then descends into a ruckus, one brought to order – in a touch whose appropriateness is amusingly evident in retrospect – by the intolerable sound of fingernails down a blackboard…

I must admit that, these days, I find Robert Shaw’s performance as Quint a bit over the top; although that said, the impossibility of thinking of the role occupied by anyone else (Lee Marvin and Sterling Hayden were considered before Shaw was cast) speaks for itself. Moreover, though they are at times hard to take, the deliberate obnoxiousness and crude humour which are Quint’s trademarks serve several purposes within what turns out to be a deceptively complex characterisation. In particular, they conceal the deeper motivations of Quint’s subsequent behaviour, and the real danger he poses to those forced by circumstances to interact with him.

But there is a danger to the viewer, too, that of overlooking the bedrock upon which Robert Shaw builds his eccentric performance; and to do so would be to underestimate his contribution to the interlocking triangle upon which so much of this film’s success rests. From the moment of his first appearance, Shaw is completely credible as a working-class man marginalised by the evolution of his town from a fishing community into a tourist resort, and whose attitude towards those in charge of this new and – Quint wouldn’t use the word himself, perhaps doesn’t even know it, but it’s the one that fits – effete iteration of Amity is charged with a mixture of resentment and contempt. The unfolding crisis and the panicky uncertainty of the town leaders, while reinforcing his own understandable prejudices, are like a gift to Quint; and as he offers himself as a solution to their problem, he barely bothers to hide his malicious enjoyment of the situation.

Positioning himself as the only person with the knowledge and the skill to deal with the shark, and reminding the business leaders of exactly how much they stand to lose if the matter is not dealt with quickly, Quint revenges himself upon the town with his demand for a flat fee of $10,000; knowing that they will not accede to immediately to such a sum; knowing too that, sooner or later, they must.

The one condition that Quint places upon his services is that he is allowed to work alone: “There are too many captains on this island,” he sneers. We note, however, that in expressing his disdain for the town leaders, Quint directs none of his hostility towards Brody. On the contrary, there is a distinct touch of sympathy in the glance Quint sends towards the chief: despite his apparent authority, Quint has recognised in Brody a man as marginalised as himself, albeit in a very different way; and indeed, one far worse off than himself, in being completely out of his depth.

The other urgent matter raised at the town meeting is the $3000 bounty that Mrs Kintner has placed upon the shark. Here another ominous detail about the manner in which the town is run emerges. We recall that Harry Meadows, the editor of the local paper, was also present when Vaughan was pressuring Brody into silence on the ferry; here we find him apologising for not being able entirely to suppress the story:

Meadows: “It’s a small story. I’ll bury it as deep as I can. The ad will run on the back with the grocery ads.”

Nevertheless, word has spread sufficiently that two local men have set out to hook and kill the shark—using, “My wife’s holiday roast” as bait.

This scene serves two purposes—simultaneously releasing some of the pressure that has been building since the encounter on the ferry via a dose of humour, yet contradictorily beginning to build that tension again by demonstrating the size and power of the shark through the ease with which it demolishes the wooden jetty to which the bait has been tethered. This is of course one of the film’s numerous moments in which the shark’s presence is only implied; but the shattering of the dock and the terrified scramble from the water of one of the fishermen conveys everything necessary.

This scene is intercut with one of the Brodys at home, with Michael’s birthday gift of his own small boat becoming now a point of contention, and Martin terrifying himself by reading up on sharks.

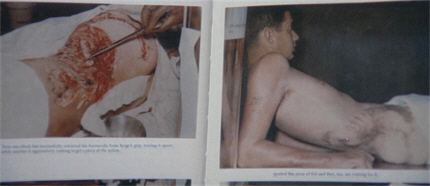

These are all real books of the time; the one whose title we are able to glimpse is The Shark: Splendid Savage Of The Sea by Jacques Cousteau and his son, Philippe. As Martin flicks through its pages we are given glimpses of the photographs contained within, including several of the appalling consequences of shark attack (another touch that emphasises the shark without needing to show it), and one of a shark with a diving-tank lodged in its mouth…

By the next morning, despite the best efforts of Harry Meadows, word of Mrs Kintner’s bounty has spread well beyond the confines of Amity. As he stares in dismay as the crowds flocking out onto the water in boats of all sizes, armed with fishing-gear of all types, Brody counters Hendricks’ suggestion that Mrs Kintner put her ad in Field & Stream with one of The National Enquirer.

But for all those heading out onto the water, there’s one person just arriving…

While the distance between Jaws the novel and Jaws the film is ludicrous in almost all its aspects, no-one benefitted from the screenwriters’ comprehensive makeover of the original narrative more than Matt Hooper, who was rescued from a characterisation that is (without getting into its details) frankly embarrassing, and transformed into one of the film’s unlikely heroes.

Possibly I’m being unreasonable here, or even hypocritical, because in its own way, Richard Dreyfuss’ performance in Jaws is every bit as blatantly idiosyncratic as Robert Shaw’s—yet I find it much easier to take, perhaps because I’m far more inclined to position myself in Matt Hooper’s corner.

But there is another and more important reason why this is so: with his own quirks and mannerisms on full display, Dreyfuss succeeds in balancing out what might otherwise be an over-intrusive performance from Robert Shaw, preventing him from dominating the frame as he could have done, to the film’s detriment.

Two vital paradoxes emerge here. Quint and Hooper, for a variety of reasons, will clash repeatedly as Jaws builds to its climax on the water, yet at the same time the film also repeatedly presents them in parallel, as it were, united – and isolated – by their understanding of the situation. Likewise, Quint and Hooper together – which is to say, Shaw and Dreyfuss together – end up throwing a spotlight on the contrasting normality of Roy Scheider’s performance, and in turn upon Brody’s unenviable position as Only Sane Man.

Be all that as it may, my adherence to Hooper begins immediately as his own dismay at the mayhem on the water and the rudeness with which he is greeted provoke him into a derisive cackle:

Hooper: “They’re all gunna die!”

(Of course he’s wrong: Jaws is far kinder in this respect than most of its copyists, nearly all of whom would include an “idiots on the loose” scene of their own, and generally use it to up their body-count.)

Hooper finally succeeds in making himself known to Brody, who with Hendricks is making a futile attempt to control the chaos around the docks: the sheriff’s relief is palpable.

Their first stop is the morgue.

Hooper’s behaviour is foregrounded here: his shock upon realising that “the body” fits in one small tray, his struggle to control his nausea as he extracts from the pitiful remains all possible information about the shark. But we should keep one eye upon the medical examiner too. If we had any doubt that he knowingly falsified Chrissie’s cause of death, we have it in his demeanour here as he waits miserably to be exposed by Hooper’s superior knowledge:

Hooper: “This was no boat accident!”

Brody also bears some of the brunt of Hooper’s angry reaction, when he learns what has not been done as a result of the coroner’s false ruling.

Though this scene succeeds in establishing Hooper’s professional expertise, the uncomfortable fact is that Richard Dreyfuss’ dialogue here is riddled with errors stemming from the long-standing but nonsensical cinematic notion that biologists tend to use Latin when referring to the objects of their study. When debating what species of shark might have attacked Chrissie, Hooper speaks first of Longimanus, the oceanic whitetip, which is correct; but he also suggests Isurus glaucus. There is no such species: presumably this is either a slip of the tongue or an error in research for Isurus paucus, the longfin mako.

But the main problem here is Hooper’s repeated use of the term squalus as a stand-in for “shark”. Squalus is indeed the Latin word for shark, but the word is never used in that general sense, not least because it is also the name of a genus of dogfish sharks: relatively small, bottom-feeding animals that have never been known to attack humans (although there have been incidents of them attacking dogs allowed to swim in the ocean). This is one of those film moments when in trying to sound smart, they end up sounding very silly.

However—in the end, perhaps the most notable thing about this scene is the species of shark that is not mentioned…

From Hooper’s conclusion, not only that a shark was responsible for Chrissie’s death, but one far larger than those commonly found in the local waters, we cut back to the docks where a noisy celebration is taking place around the dead body of a tiger shark.

Again— I understand that in the mid-70s, it probably wouldn’t have occurred to anyone faking this scene was desirable; that there was any problem with providing the production with a dead shark just by going out and killing one. Even so, killing one isn’t what they did: they kept killing sharks until it finally dawned on everyone that they weren’t going to catch one locally big enough to act as a credible stand-in for the film’s monster.

At that point the decision was made to import a dead tiger shark from Florida, where they do commonly run to 18 feet in length (though this one is only around 13 feet, much too small to have done the damage recorded in Chrissie’s remains). The animal was flown to the set by private plane, but even so, by the time it arrived decomposition had set in, making this scene deeply unpleasant for everyone involved.

To which I can only respond—good.

As the excited townspeople crowd around the shark, we note that Harry Meadows, far from hushing up this part of the story, is issuing orders to his assistant: “See if Boston’ll pick it up, and go national!” Brody and Hooper then arrive, and former responds with unbounded relief and glee at what he assumes is the end of the nightmare. Hooper, however, is quietly measuring the animal’s bite radius…

We then pull back to Quint, passing in his boat, and see him laughing scornfully.

Brody has rushed off to drag an equally relieved Larry Vaughan to the scene, and by the time he gets back he finds Hooper at the centre of an angry mob, enraged by his suggestion that this may not be the shark they want. As Brody pulls him out of there, Hooper begins walking a thin line, not wanting to provoke the same response from the sheriff, but needing to convince him that they have to be sure; that they must cut the shark open and examine its stomach contents to be sure.

But in making his argument, Hooper oversteps his own line: intent upon the necessary proofs, he is insufficiently conscious that “whatever it’s eaten” may be a small boy; a local boy. Vaughan, dismissive as he was of poor Chrissie, is outraged by Hooper’s careless choice of words, and correct that, “This is neither the time or the place.” Behind this justified reaction, however, we see a deep reluctance to face facts.

The matter still hangs in the balance when there is a new arrival on the scene. Mrs Kintner, swathed in black, has come to see the animal that she believes took her son; but she has also come to confront the man she holds responsible for its doing so; the man who, she has just learned, knew there was a shark in the waters off Amity, and said nothing…

Mrs Kintner’s verbal attack on Brody, quiet and controlled as it is, is brutal; far more brutal than the face-slap which accompanies it. Vaughan, embarrassed by the scene – and, we hope, by his own part in Brody’s inaction – offers consolation: “I’m sorry, Martin. She’s wrong.”

“No, she isn’t,” says Brody.

Nor is she. Brody knows that he has been weak, too easily swayed by arguments whose falsity he could recognise even through his own inexperience and ignorance of water matters. He could have insisted upon the beaches being closed, or at least made a sufficient ruckus to alert others to the potential danger, but he did not; he did not even (as Hooper pointed out to him) take the elemental and non-controversial precautions of alerting the Coast Guard or patrolling the waters. Though there are good excuses for his passivity, they are only excuses; the responsibility was his, and he abrogated it. Alex Kintner’s death is his fault.

Brody accepts the painful reality of his own failure, which will drive his behaviour for the rest of the film. First, however, it drives him into a bottle…

One of the most remarkable things about Jaws is that its character scenes and its dialogue are every bit as gripping as its action scenes; in some respects, perhaps even more so; and I think you can make an argument that the five-minute sequence which follows Mrs Kintner’s denunciation of Brody is the best scene in the film—even though it consists of little more than three people talking.

But perhaps that should be because it consists of little more than three people talking. The dinner-table scene at the Brodys’ house is film-making at its finest: it is tense, it is funny, and it is profoundly revealing of character. It is a scene you can watch over and over for the sheer enjoyment of it.

It opens which a touch which we must still appreciate in spite of (what was by then) the Jaws franchise’s attempt to ruin it retroactively: Brody’s interaction with Sean, who mimics his father’s gestures back at him while Ellen, amused and moved, watches in silence. Brody demands a kiss from his son – “I need it” – but it is not enough to heal the wounds inflicted by Mrs Kintner and his own guilt.

Ellen’s watchfulness throughout this interlude is fascinating, as is the very fact that she says so little. We are reminded in this scene that she is not just a cop’s wife, nor even just a New York cop’s wife, but a 1970s New York cop’s wife; we can imagine the pressure and the fear she has had to endure—perhaps silently, as now.

We gather along the way in Jaws that it was Ellen who insisted upon the relocation of the family to Amity. As she watches her husband sinking into inebriation, we are left to wonder whether it wasn’t moments just like this that prompted her to make a stand—and whether she isn’t watching once again a scene she thought safely behind all of them.

But it is Matt Hooper who pulls Brody back from the brink—not for unselfish reasons, but because he needs him, and needs him functioning.

The scene on the dock tells Hooper everything he needs to know about the situation in Amity: that there is still a danger of it all being swept under the carpet; that Brody is the one man with the authority and the inclination – and the character – to stop that happening; but conversely that, between his ignorance and his guilt, there is also a real possibility of Brody withdrawing himself and letting events play out as they might.

What has brought Hooper to Brody is an overheard remark from Vaughan indicating that the tiger shark is to be disposed of on the following day. If the necropsy is to be performed, then, it must be at once. Hooper’s barging in, both into the house – “The door was open.” – and at dinnertime is overtly rude, but indicative of the urgency of the situation. (His appropriation of Brody’s uneaten dinner is, however, just him.)

But in spite of all its tensions, this is as I have said also a very funny scene—the tone set by the quiet exchange between Hooper and Ellen that starts it – “I’d really like to talk to [your husband].” “Yes, so would I.” – and the latter’s hilariously awkward conversation-starter:

Ellen: “My husband tells me you’re in sharks.”

The conversation – mostly between Hooper and Ellen – encompasses the former’s love of sharks and Brody’s fear of the water, as well as Hooper’s belief that the shark has not been caught, and it has the desired effect: it is Brody who suggests that they go and cut the tiger shark open—after “one more drink”…

The result is exactly what they feared: the tiger shark disgorges partially digested fish, a tin can and a Louisiana license-plate…but no human remains.

Brody comments numbly that he has to call the mayor and close the beaches. Hooper retorts that he, they, have to do more than that: they have to go find the real shark; now; at once.

(Yet another mark of a great film is that no matter how many times you watch it, you can always spot something new. It was only on this viewing of Jaws that I properly absorbed the fact that Brody supports his assertion that he is, “Not drunk enough” to go out on the water – at night – looking for a man-eating shark – by taking with him Hooper’s second bottle of wine…)

Using Hooper’s boat, which is laden with expensive equipment, the two men patrol the area in which they believe the shark has established its territory. They don’t see the animal, but they do come across an apparently abandoned boat that belongs to fisherman, Ben Gardner. The boat is lying low in the water, “all banged up” and with a half-circle piece missing from one side. There is no sign of its owner.

Under Brody’s incredulous gaze, Hooper changes into diving-gear in order to examine the boat’s hull. Slipping beneath the vessel, he examines it with a powerful light, discovering a jagged hole in the boards—in which is embedded an enormous tooth.

And as Hooper works at the hole, what’s left of Ben Gardner’s mutilated body drifts into his line of vision…

Hooper flails for the surface, in his terror dropping both his light and the shark’s tooth. Loss of the latter evidence proves critical when, the following day, he and Brody confront Larry Vaughan, who stubbornly resists their arguments—and perhaps with some reason.

Though he is trying to be helpful, Brody’s panicked reiteration of Hooper’s assertions – which are being made hotly enough on his own account – has the effect of making them seem exaggerated, giving Vaughan grounds to go on disbelieving. And of course Hooper can’t produce the tooth that would have supported his claims.

(Perhaps the best measure of how Jaws changed everything is the reminder offered here that there was a time when laypeople did not know what a great white shark was…)

Something else is in play here, however. Jaws was notoriously a film made on the run, with significant alterations to the script being made along the way to cope with or cover up its production challenges. One of the consequences of this is a raft of continuity errors, which are evident enough if you pay attention to the mentioned dates and other discussions around the timing of the fatalities—and their number. For example, Brody’s initial police report gives Chrissie’s date of death as the 1st of July, but when Mrs Kintner places her bounty, Alex’s death is supposed to have occurred on the 29th of June. It is evident that a lot of mind-changing went on during filming and post-production, and the results are not always hidden.

Spielberg is on record as having chosen to re-shoot the finding of Ben Gardner’s body during post to make the scene more “jump-worthy”. While there’s not much question that he succeeded, it is evident in retrospect that in the first place, his body wasn’t meant to be discovered at all—which would have worked better in the context of Hooper and Brody’s failure to convince Larry Vaughan of their claims.

Thus, we are left with Brody telling Vaughan about Gardner’s boat being “all chewed up”, and pointing out that [Amity has had], “Two people killed within a week.” But no mention is made of Ben Gardner’s death.

It is therefore not wholly unjustified that Vaughan chooses to go on believing that the killer shark has been caught and killed. The more the others press, the more Vaughan shuts down, finally ending the conversation by complaining about the vandalism of a billboard, into which a shark has been graffitied. He then departs, telling Brody on his way out to do whatever he has to, to keep the beaches safe—short of closing them.

As he drives off, a ferry arrives from the mainland, disgorging tourists in their hundreds…

At first glance everything seems normal in Amity on the 4th of July weekend. A second glance reveals signs of agitation that have nothing to do with the size of the crowds. Helicopters patrol overhead; boats manned by men with guns cruise offshore; Brody paces at the water’s edge, monitoring the walkie-talkie communications between the spotters.

And then there’s the fact that no-one is going into the water.

It is Larry Vaughan who takes care of that—not personally, but by urging a reluctant town councilor to make the first move. He then responds to a request for a TV interview (by a cameoing Peter Benchley, who nails the facile absurdity of such “human interest” bits) – stressing the killing of a shark that, “Supposedly injured some bathers…”

The entry of the councilor, his wife and their grandchildren into the sea does begin a general movement down the beach, and soon the waters are filled with people swimming and splashing. However, as Michael and his friends carry his small boat towards the gentle surf, Brody intervenes—asking Michael to take the vessel out on the quiet, partially enclosed area of water known as “the pond” instead. The boy groans, but obeys; and as he and the others head down the beach and across the road, Sean bolts after them, uttering an indignant protest about being ignored.

And mere moments later, a fin cuts through the water behind the main group of swimmers…

Well. Those of us who have been paying attention shouldn’t be fooled, because as this “shark” glides into the midst of the swimmers, there is no music.

From beneath the gliding fin emerge two young boys, whose tasteless practical joke undoubtedly got more of a reaction than they anticipated—and who probably find themselves facing more blow-back than they ever dreamed, after the panicked stampede towards shore leaves several people injured.

The head lifeguard tries to quell the crowd’s panic with a soothing announcement that it was all just a joke. As his amplified voice sweeps down the beach, it almost drowns out the hysterical screaming of one young woman as she stares in horror towards the waters of the pond…

This scene offers our first good glimpse of the shark, as it attacks a man unfortunate enough to row his small boat between the animal and Michael and his friends, leaving its victim dead and dismembered and Michael, who has a literal brush with death as the sated shark departs, in a state of deep shock.

(We should note this moment for historical purposes: the shark, having just killed and eaten, swims off without attacking anyone else. Going forward, it would be a rare killer animal film indeed that would privilege such realism over its body-count. Even this film ceases to do so…)

So terrified is Brody for his son, he rushes into the water without even thinking about it, in order to help pull him out. Michael is rushed to the hospital, where his parents are reassured about his condition, though the boy is kept in overnight as a precaution.

Having sent Ellen home with Sean, Brody then drags the hovering Larry Vaughan into a cubicle, demanding his authorisation for the hiring of Quint. It takes him a few minutes to get his message through to the shell-shocked Vaughan, who is still coming to terms with the fact that in his determination to prove – to believe – that the water was safe, he placed his own children in danger, but in the end Brody gets that signature.

This is Quint’s big opportunity—and he is not slow to take advantage, appending to the $10,000 dollars a list of further demands that span everything from Brody “getting the mayor off my back” over zoning to a new colour television.

But Quint’s genial mood fades as soon as he realises that Hooper is being forced upon him as a boat-hand. In spite of Quint’s declaration at the town meeting that he would have “no mates” and “no volunteers”, Brody has made it a condition of the contract that both he and Hooper should be a part of the hunt.

Brody’s own involvement in the shark hunt has two faces. It is his job, his responsibility; but on a deeper level it is also something like an act of penitence for his failures, real and perceived. Nevertheless, we can appreciate that for Brody, the only prospect more appalling than hunting for a shark on the open water is doing so alone with Quint.

The inherently clashing personalities of Robert Shaw and Richard Dreyfuss here pay off in the antagonism that quickly develops between Quint and Hooper. The general contempt expressed earlier by Quint for Amity’s business community focuses into a laser-like beam of active hostility directed at Hooper, who is – or appears to be – everything the fisherman most despises: an individual of privileged background, a “college-boy”, wealthy enough to indulge his hobbies as a career, without any need to actually work—that is, to do anything Quint recognises as “work”.

To a man like Quint, everything about Hooper is offensive, from his “city hands” to the expensive equipment with which his own expensive boat is fitted, and which he brings aboard Quint’s own battered and hard-worked vessel, the Orca. From the moment he gets Hooper under his command – even before that, from the first moment they meet – Quint makes it his mission to embarrass Hooper and to expose what he considers his weaknesses by riding him as hard as he possibly can.

Whatever we make of Quint’s behaviour towards Hooper, there is no question that this treatment brings out the very worst in its target, provoking a petulant, spoilt-brat reaction that goes a long way towards justifying Quint’s prejudices.

However, we need to consider the matter from Hooper’s point of view. From the moment he sets foot in Amity, he is abused and/or treated with contempt by the locals, with Quint’s class-conscious attacks merely the extreme expression of a general attitude. His expertise, his motives, even his word, are called into question.

Yet we know he has given up, or at least cut short, an eighteen-month-long oceanic research expedition in order to stay in Amity and help deal with the shark. Hooper makes no overt complaint about this, nor does anything to draw attention to his sacrifice; he merely lets his colleagues know that he will not be joining them. His excuse – that he has a great white here – is just an excuse, since his purpose in staying certainly isn’t research.

During the dinner scene, Hooper remarks that after his own departure, Brody will be the “only rational man” on the island. After the confrontation with Vaughan, however, it is clear to him that one rational man will not be enough. So he stays—risking his life in a matter in which he has no personal, no financial and little professional stake; nothing beyond a recognition of Amity’s general and Brody’s specific need of him.

And this is the thanks he gets?

(All my sympathy with Hooper cannot prevent me from wincing at Richard Dreyfuss’ second-syllable-stressed pronunciation of “Brisbane”.)

And there are two other aspects of Quint’s conduct that we need to consider: first, that it is dishonest: for all that he overtly questions Hooper’s qualifications and expertise at sea, any moment that he must rely upon him to do the correct thing he simply does so, knowing that he can; and second, that it is dangerous, a deliberate ratcheting up of tension that both distracts Hooper from the matter at hand and plays upon Brody’s shredded nerves and feelings of inadequacy.

In fact, this behaviour on Quint’s part is our first real intimation that a great deal more is going on with him than his reluctant colleagues realise.

From this point, just over halfway into the film, Jaws plays out entirely upon the water. One of Spielberg’s cleverest touches in this film, another of those things that you may not consciously realise while watching, is to crowd its first half with images of enclosure. Fences abound – wooden fences, picket fences, wire fences, dividing fences – carrying with them a mingled sense of restriction and safety. The motif is insistently present from the very first moments of the film proper, so when the action transfers so swiftly and so completely to the open ocean, the effect is jolting, if only on the psychological level.

The setting for the ocean filming for Jaws, off Martha’s Vineyard, was chosen with great care—keeping the necessary proximity to land for the benefit of the film-makers, and offering water not too deep for either safety or visibility, but at the same time with absolutely nothing but water visible in any direction.

And once on the sea, Spielberg takes his time about things—introducing what the viewer needs to know about the geography and operation of the Orca through clever dialogue that never once feels info-dumpy. Onboard, the dynamics between the three men continue to shift and evolve. Much as Quint and Hooper despise each other personally, their expertise aligns them and isolates Brody, who is relegated to the disgusting task of shovelling out chum. Meanwhile, Quint’s riding of Hooper continues unabated.

We note, though, that Quint’s treatment of Brody is in some ways better than Hooper’s own: while the latter berates Brody openly for his mistakes, Quint – while willing enough to mock him in a general way – only ever criticises him privately. In this we see his respect for someone who, be he ever so ignorant about the sea, is nevertheless a working man with a dangerous job. In this, it is Quint and Brody who are aligned, and Hooper the outsider.

But these “quiet” scenes serve another, and much more important purpose: they lull the viewer into a false sense that nothing is really happening—thus setting up one of cinema’s most brilliantly executed shock moments…

The entity who has since become known to the world as “Bruce” was realised via a set of animatronic models designed by Joe Alves: a mostly full-body construct, and two partial ones for shooting either from the left or from the right. Various external circumstances saw production of Jaws brought forward, meaning that filming began before the screenplay had been completed, and before the model sharks had been properly tested in water – any water – never mind salt water. During his very first outing before the cameras, Bruce sank, giving the waters of Nantucket Sound the first of many opportunities to eat away at his electronics.

It is now a matter of some debate how much Spielberg originally intended to show the shark in Jaws. His insistence that he always meant to hide it for most of the film may be retconning, although we do know that it was never going to appear during either the opening attack on Chrissie or the destruction of the wooden jetty. The attack on Alex Kintner was actually planned as the shark’s first big appearance, but this was altered not because of malfunctioning models, but because on later consideration the footage of the child’s death was considered too graphic and upsetting.

So as things stand, we get no more than a quick glimpse of the shark during the pond sequence, before its jolting appearance as Brody chums the water.

The shortcomings of Bruce, both generally and specifically, are evident enough—though we should probably keep in mind that when Jaws was made, very few people actually knew what great white sharks looked like, still less how they behaved. Still—the fact is that this shark does things that no shark could or would do, while not doing things that it should be doing. Perhaps the most intrusive example of this is that the model sharks were designed in permanent feeding posture—yet without the real great white’s horrifying ability to thrust its jaws forward as it attacks and eats. Another distracting detail is the jowly folds at the corners of the shark’s mouth, obviously a consequence of the design of the pneumatics by which the mouth was operated.

But you know what? – it doesn’t really matter. In this respect, watching Jaws is like watching a Godzilla movie: by the time the shark shows itself, we are so invested in it that the brain simply accepts what it sees. And of course, the fact that it is a model means that the characters can interact with it in a way that would not be possible with a visual effect.

Moreover, this introduction of the animal, the perfection of timing in this scene, just makes the heart sing. And perfection is piled upon perfection in Roy Scheider’s physical playing of Brody’s response to his first look at the shark, and our knowledge that the verbal response was ad-libbed:

Brody: “You’re gunna need a bigger boat…”

Brody’s terror is one thing; Quint’s shocked disbelief when he first lays eyes upon this enormous predator is something else, and tells us exactly what the men are up against. There is, meanwhile, a level of delight in Hooper’s whispered estimation of a twenty-foot-long animal, which Quint quietly corrects to twenty-five…

(Twenty feet remains the record confirmed length for a great white shark, though others of an estimated twenty-one and twenty-three feet have been spotted. Any shark of that size will almost certainly be female; though on the other hand, males are more aggressive, so perhaps we can excuse the characters’ automatic use of “he”…)

Hooper’s outrageous response to the shark’s appearance is to try and persuade Brody to go out right to the end of the boat’s “pulpit”, a task he indignantly refuses once he understands that Hooper simply wants something to give scale in his photographs.

Meanwhile, Quint has intercepted a check-in call from Ellen—assuring her that everything is fine, and that they have not yet found the shark…

Hooper, we note in passing, calls the shark “darling” while trying to get his photographs, but this attitude in no way interferes with his assistance with Quint’s preparations for harpooning the animal with ropes and drags; though he does attach one of his own electronic markers to the first barrel. Quint starts out assuming that one barrel will “bring him up”, but night has fallen before the animal is seen again.

Prior to this, the three men do the sensible thing and get a little drunk.

This is, in its first instance, perhaps the funniest scene in the film, adding to the stunning impact of the subsequent lurch in tone. It amounts to Quint and Hooper burying the hatchet – topping each other with their many scars and their tales of how they got them – though their doing so isolates Brody once again.

But it is Brody who notices and asks about the scar on Quint’s left arm, which he explains is from having a tattoo removed. After a moment’s hesitation he tells Hooper that the tattoo did commemorate his service on USS Indianapolis. The revelation chokes the laughter in Hooper’s throat, as he stares at Quint in dawning horror.

Brody, however, does not know the story; so Quint tells it to him…

Now— Do I get into this here? I think I have to; though I’ve been abused before by people who have misunderstood what I’ve been trying to say.

Briefly, then— In July 1945, the Indianapolis was given the top-secret assignment delivering to Tinian, one of the Northern Mariana Islands, various components of the atomic bomb including the Uranium-235 that was to catalyse the detonation. It was then ordered to Leyte Gulf, in the Philippines. However, just after midnight on the 30th of July, the Indianapolis was struck by two Japanese torpedoes and sank within a mere 12 minutes. Of its 1197-strong crew, 880 men survived the initial attack and made it into the water. By the time help arrived – five days later – only 316 of them were still alive.

There is no doubt that, in Jaws, Robert Shaw delivers one of motion pictures’ all-time great monologues, as he describes the nightmare experiences of those survivors—and of those who lost their lives. Particularly indelible is his recollection of when the sharks came:

Quint: “A shark, he’s got lifeless eyes. Black eyes, like a doll’s eyes. When he comes at you, he doesn’t seem to be living…until he bites you, and those black eyes roll over white, and then…then you hear that terrible high-pitched screaming. The ocean turns red…”

The problem is, though—it didn’t happen the way Quint tells it. In reality, the men who died of shark attack after entering the water were a minority; the majority died of their injuries, or of exposure or dehydration, or from drinking sea water; and the sharks—well, there’s no gentle way of putting this: they’re scavengers; it’s what they do.

Now—I am not for one second suggesting that this version of events is any less horrifying, any less traumatic, than Quint’s version; or that someone might not, or should not, come away from such an experience with a phobic hatred of sharks. Nor am I (as I have been accused of doing in the past) trying to defend the sharks at the expense of the servicemen who lost their lives.

Anyway, I know I’m on the same page here as both the survivors of the Indianapolis and their families, and the navy itself. Serious efforts have been made over the past couple of decades to get the real story into the public record, partly out of anger at the way that this complex and tragic incident has been variously misreported and misrepresented over the years, even by reputable publications and documentarians—who, even when they get it right in outline, nevertheless always end up focusing on the sharks, almost to the exclusion of the rest of the story.

There is no getting away from the fact that Jaws is largely responsible for creating this scenario. This film – this scene – is where the vast majority of people who think they know about the Indianapolis got their information. And what they think they know is the clear implication with which this scene leaves us: that the men in the water would have been just fine if not for the sharks.

What I find frustrating is that it could easily have been handled differently; there could have been a way of maintaining the horror while making it clear that this is not necessarily what did happen, but rather Quint’s memory of what happened. Hooper, perhaps, could have started to interrupt – “But that’s not what—” – before realising that correcting Quint would not only be futile, but profoundly disrespectful.

It is left to Hooper to break the mood induced by Quint’s speech, which he does by leading the other two in a rowdy chorus of “Show Me The Way To Go Home”.

(This song became a significant motif for the cast and crew of Jaws: trapped at sea in the middle of an apparently interminable film-shoot, the lyrics gained the power to provoke a Pavlovian burst of tears from all concerned.)

However, this companionable moment does not last long: it is interrupted by something slamming against the side of the boat, cracking the boards and allowing a dangerous flow of water into the engine-room.

The men deal with the immediate crisis, and the rest of the night passes without incident. The morning reveals the extent of the damage, with saltwater in the fuel and the steering almost out of commission. Though their joint efforts improve the situation, oily smoke is still rising from the boat’s depths when that one barrel suddenly reappears…

This is enough for Brody, who makes a grab for the radio. He is still trying to reach the Coast Guard when he sees, as he thinks, Quint coming for him with a baseball bat…but actually intent upon smashing the boat’s – one – radio…

(Oh, Jaws: you have such a lot to answer for…)

This is the moment when Quint’s mask drops, when the real significance of his earlier remark, that he never wears a life-jacket any more, becomes frighteningly clear. This is Quint-as-Ahab, of course, and like Ahab, he doesn’t much care what happens to those people who get in the way of his obsessive quest for vengeance.

Hooper is as appalled as Brody with the radio situation, but as the barrel comes towards the Orca, he knows that there are more pressing things to be dealt with. The first barrel is retrieved – just – and he and Quint between them place another two into the shark’s hide, pursuing the animal as it heads away from them. Quint yells repeatedly for more speed, but with the Orca still belching smoke there is only so much Hooper can do. He yells back at Quint that he dare not push the vessel past a certain point.

Even so, they catch up with the shark and as it passes the boat, Brody lines it up with his service pistol and sends a series of bullets into it. This has no noticeable effect on the animal, but it does indicate the frustrated Brody’s desire to make a real contribution to the hunt. It also demonstrates for us that he is a pretty good shot…

To the men’s consternation, both barrels then submerge. They reappear again, at a greater distance from the boat.

Spielberg, of course, does not suggest that the shark is deliberately leading its pursuers further and further from shore – it would take some of this film’s less clear-headed copyists to introduce that detail.

As Quint manoeuvres the boat, Hooper and Brody snag the ropes attached to the barrel and wind them around the cleats at the stern. Brody’s clumsiness here traps Hooper between the rope and the side of the boat, with nearly disastrous consequences; but once he has been rescued the men see cause for celebration, assuming the shark caught. Quint even starts talking about a taxidermist acquaintance…until Brody cries out in alarm that the cleats are being pulled free.

Quint puts a third barrel into the shark, but even this cannot stop the animal, which begins to pull the boat in the other direction, against its own course. The opposite forces being exerted put the boat in danger of being literally torn apart; it bucks frantically, with water spilling over its sides and sweeping down into the engine. Finally the cleats are torn away from the transom, freeing the boat.

Three yellow barrels bob at a distance, then turn back towards the boat. “He can’t stay down with three barrels on him,” Quint snarls. “Not with three he can’t.”

But go down he does—directly under the boat. There is a tense pause before the anticipated impact, which causes the Orca to lurch in the water. At this, even Quint is prepared to turn back towards land—only for the shark to follow.

If we were unconvinced by Quint’s insistence about the three barrels, we are even less so by his plan to, “Draw the him into the shallows and drown him.” All Brody knows, though, is that they’re finally headed for shore: “Thank Christ!”

But— Well, how do we interpret what Quint does here? Sheer bloody-minded stubbornness—or a death-wish? Hooper urges Quint to release some of the pressure on the boat’s struggling engine, and he – whistling cheerfully – does the opposite, ramping the pressure up more and more with each frantic remonstrance from Hooper…until the inevitable happens. An explosion rips through the engine-room, leaving the Orca becalmed and slowly sinking, and still pursued by the shark.

Quint throws life-vests to Hooper and Brody; he does not don one himself.

It is a measure of the desperation of the situation that Quint then asks about Hooper’s equipment, with which (as the latter tried to suggest earlier) they might be able to kill the shark. Hooper explains that he has a dart-harpoon with which he can pump poison into the animal. The only problem is, the needle can only penetrate the shark’s soft tissue—which is to say, the inside of its mouth. And that means getting into the water with it…

The novel-version of Matt Hooper does not survive the narrative of Jaws, becoming instead the target of some rather obvious cosmic justice for his various transgressions. It was Spielberg’s original idea to kill off his Matt Hooper too, albeit more in the sense of a heroic sacrifice, but circumstances intervened.

The shark-cage footage in Jaws was shot by – surprise! – Ron and Valerie Taylor. A logistical problem was posed by the unnatural size of the film’s shark, which Spielberg solved by hiring former jockey, Carl Rizzo, who was only 145 centimetres (4 ft 9 inches) tall, to double for Richard Dreyfuss in this scene. (Rizzo’s greatest claim to fame at the time was doubling for Elizabeth Taylor during the shooting of National Velvet.) With everything scaled accordingly, the sharks filmed by the Taylors, which averaged a normal 14 feet, looked much bigger.

That at least was the theoretical solution. However, Rizzo had had no previous diving experience, and was utterly terrified from start to finish (adding another difficulty to the shoot by burning through the oxygen in his miniaturised tanks). His increasing resistance to getting into the water forced the Taylors to supplement the footage featuring Rizzo with more featuring matching dummies.

Another difficulty was getting the sharks to co-operate (no, really). One day, while Ron Taylor was working near an empty dive-cage and trying to figure out the best way of attracting the animals, one shark not only came into camera-range but managed to get its snout caught in the bridle attaching the cage to the Taylors’ boat…and promptly went berserk.

Spielberg, viewing this sequence, thought it was the best and scariest footage of all that captured, and determined to use it in the film—thus granting Matt Hooper a reprieve: instead of dying horribly as planned, he was allowed to escape and take refuge on the sea-bottom, while the shark attacks and destroys the now-empty cage.

And you know? – as with so much in Jaws, I think this was accidentally the right thing to do. Even in light of the 1970s’ many mean-spirited film-deaths, Hooper’s death would have been an unnecessary downer.

But up above, all Brody and Quint know is that the cage has been dismantled and Hooper is nowhere to be seen…

They have no more than a moment to contemplate the situation, however, nor Brody to grieve. Suddenly, the shark launches itself at the low-lying Orca, slamming down on the transom and smashing it, and forcing the boat’s stern down into the water. The upwards lurch of the body of the vessel sends both men flying—and leaves Quint sliding inexorably down his own deck towards the gaping maw of the shark, as his own worst nightmare comes true…

And that leaves Brody: water-phobic landlubber Brody. Sickened and terrified, he barely has time to retreat into the cabin before the shark plunges through the side of it. Brody scrambles backwards, desperately seeking a weapon, but all that comes to hand is Hooper’s spare oxygen-tank. After landing one blow with it, Brody throws the tank at the animal which, to his bemusement, swims off with it in its mouth.

As the Orca tips over on its side, Brody scrambles out of the hole in the opposite wall of the cabin and up onto the bridge, where he finds Quint’s rifle and a long wooden-handled marine spike. From there he climbs up the mast. He has barely reached the open crow’s nest before the shark lunges for him.

Gasping with terror, Brody fights back with the spike. He loses his weapon in the struggle, but succeeds in driving the shark away—for the moment.

Given this brief respite, Brody braces himself against the crow’s nest. By this time the continued tipping of the boat, to which his own weight is contributing, leaves him almost lying on the surface of the water.

Sure enough, the shark returns. Brody aims his rifle—not just at the animal, but at a very specific target: during the last brief encounter, he noted that the oxygen-tank was still wedged in its mouth. He fires again and again, to no effect, as the shark closes in on him—

Brody: “Smile, you son of a—”

Well. I had my doubts about the logistics of this ending the first time I ever saw Jaws, and I cannot say they have lessened over time. However, they have also by now been thoroughly Mythbusted, so it probably isn’t necessary for me to get into the details. I will simply say that my main objection remains what it always was, that when Brody first grabs that tank it is floating, meaning that it is empty, or nearly so; that at least, it does not hold enough compressed oxygen to bring about the desired result. And even if it were full, though the rupture would no doubt do enough damage to stop the shark, it would hardly result in the spectacular explosion that does finally put an end to the film’s menace.

Still—there’s no doubt at all that Jaws earns the right to out with a bang…

Though of course, that isn’t the actual ending, which is far (and appropriately) quieter:

Brody: “I used to hate the water.”

Hooper: “I can’t imagine why…”

Jaws is a rare piece of art—a film you can watch again and again with ease, in which there is not a wasted moment in its just-under-two-hours running-time. It’s a miracle of film-making, one all the greater for being based – let’s not beat around the bush here – on a terrible book, a poorly written potboiler that lucked out by tapping into the zeitgeist with its one good idea.

That Jaws has lost none of its impact – none of terror, none of its fun – over the intervening decades speaks for itself. It is one of those cinematic acts of serendipity, a film that completely defies the odds – and the odds against Jaws even being good, let alone great, were astronomical – in becoming so much more than the sum of its parts. Literally everything works here; at least, it works in front of the cameras, whatever disasters, arguments, breakdowns, food-fights and desperate instances of patchwork film-making were going on behind them.

Something that the film has gained by now, or rather that we have gained, is perspective: it is fascinating to re-watch Jaws as “a Steven Spielberg film”, knowing what we know now about the director he was to become—and in some respects, sadly, the director he would cease to be. I’m not sure that any subsequent Spielberg film is as purely cinematic as Jaws; Raiders, maybe. A few film-school tricks aside, like the reproduction of Hitchcock’s famous “pull-away zoom” from Vertigo during the attack on Alex Kintner, this is a clean, crisply directed film.

There is also a youthful ruthlessness at work here, an absence of the second-guessing and sentimentality that would increasingly plague Spielberg’s later works, as increasing popularity and success brought in their train a similarly increasing self-consciousness. The later Spielberg killing a child and a dog – in the same scene! – is literally unimaginable; but in 1975 he did it, just because it was right for his film.

But while I don’t want to underestimate what Spielberg brought to Jaws, each time I watch it I am more and more aware of the magnitude of three other contributions, without any one of which the film would not be a patch on what it is, and which together raise it to rarefied heights.

One of these, which we have discussed already, is that of John Williams, whose score rightly won the year’s Academy Award. (Williams was conducting the orchestra at the Oscars that year, and had to climb up from the pit to accept his award—and then climb down again, to get back to work.)

The second vital factor is Verna Fields’ editing. At its most obvious – which is not to say it is ever intrusive – Fields’ cutting gives a brilliant rhythm to the film, increasing and releasing the tension throughout, and effortlessly manipulating the audience’s reactions.

But that isn’t all she did. As we know, this was a rolling disaster of a film-shoot, full of things going wrong and sudden or necessary changes of direction, all of it bundled up in those two great enemies of continuity, water and weather.

And yet the completed film is – as far as it can be – seamless. Where it is not, matters were beyond Fields’ control, as with respect to the previously mentioned continuity errors surrounding the dates on which the various incidents are supposed to have occurred, where the directorial change of mind came too late. Similarly, the timeframe of Alex Kintner’s death, the placing of Mrs Kintner’s ad, the town meeting and the arrival of the bounty-hunters is far too compressed to be credible. However, other than the non-mention of Ben Gardner’s fate, these are probably details that only the obsessive (or the compulsive re-watcher) is really likely to notice.

But for those of us who do pay close attention, we are left with a sense of Jaws as quite as much Fields’ masterwork as Spielberg’s; perhaps even more so. At any rate, both her peers and her bosses recognised her role in the film’s success: she too took home an Academy Award, and was subsequently promoted at Universal to the position of Vice-President for Feature Production. Yet perhaps the greatest compliment paid her was the nickname she acquired on-set: “Mother Cutter”.

Meanwhile—the journey of Jaws, the novel, into Jaws, the movie, was convoluted enough to be almost the film-shoot in microcosm. Peter Benchley himself wrote the first draft, but struggled with the translation from novel to screenplay. Spielberg then took a stab at it, but most of that version remained unused too. The director certainly did contribute to the script, but his material was added later, during production.

The playwright Howard Sackler was brought in for rewrites, but translated the novel so faithfully he kept all of its shortcomings, so most of his work wasn’t used either—with one vital exception. It was Sackler who had the idea to use the Indianapolis as Quint’s backstory, though at the time he provided only a short outline. John Milius, with whom Spielberg discussed the matter simply as a friend, then asked if he might take a crack at fleshing out Sackler’s draft—but did so too much, turning the speech almost into a script in its own right. His lengthy document was then handed over to Robert Shaw, and it was the actor who cut it down into its final, unforgettable form.

Ultimately, however, the person chiefly responsible for shaping the screenplay of Jaws into its definitive form was Carl Gottlieb, who had worked with Spielberg previously as an actor, and who had already been cast as newspaper editor, Harry Meadows, when the screenplay woes began to unfold. The ever-extending production schedule gave Gottlieb plenty of time to tweak and polish his work, to integrate into his script various requests from Spielberg – and some necessary changes – and the fruits of his lengthy discussions with Scheider, Dreyfuss and Shaw about their characters.

Like everything to do with Jaws, the final version of the screenplay gives little evidence of the chaos of its development; but as with Verna Fields’ editing, the more often you watch this film, the deeper becomes your appreciation of Gottlieb’s contribution. The writing is so clever, yet so natural in its cleverness, that it is easy to overlook its real quality. Nothing is wasted here; every line, every interaction, every gesture contributes to the richness of detail that makes this film such a rewarding viewing experience. For instance, I was struck this time by Brody’s shifting language on the boat, as he acquires the correct terminology through experience.