“What the hell’s a million year old grizzly doing here!?”

Director: William Girdler

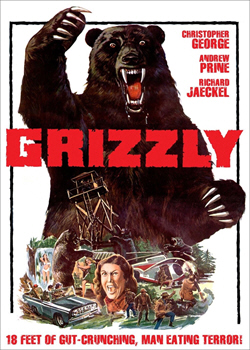

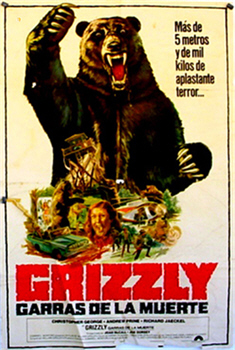

Starring: Christopher George, Andrew Prine, Richard Jaeckel, Joan McCall, Joe Dorsey, Tom Arcuragi, Vicki Johnson, Charles Kissinger, Kermit Echols, Maryann Hearn, Catherine Rickman, Harvey Flaxman

Screenplay: Harvey Flaxman and David Sheldon

Synopsis: Faced with managing unexpectedly large crowds, Head Park Ranger Michael Kelly (Christopher George) briefs his team before sending them out into the field to try to watch over all the campers and hikers. Two of the rangers, Tom (Tom Arcuragi) and Gail (Vicki Johnson), try to make arrangements to go on patrol together, but the grinning Kelly has other ideas, keeping Gail at the ranger station. Photographer Allison Corwin (Joan McCall) expresses her concern over the way her father, Walter (Kermit Echols), is running his tourist lodge. Their conversation is broken up when Kelly reminds Allison that she was supposed to be joining him on patrol. Out in the woods, two campers, Margaret (Maryann Hearn) and June (Catherine Rickman), are startled by the appearance of Tom on horseback. They assure him that they intend to be down well before dark. But the girls never make it: they are bloodily killed by something that emerges suddenly from the woods… Kelly and Allison are met on the road by Tom, who is worried by the non-appearance of the two young women. They search, and in the shattered remains of an old shack, Kelly finds a mutilated body; later, Allison literally stumbles over the other. Dr Samuel Hallitt (Charles Kissinger) confirms that both were victims of a bear attack. Park Supervisor Charles Kittridge (Joe Dorsey) storms in angrily, wanting to know why Kelly didn’t notify him personally of the tragedy. Kelly reports that he has his entire team searching for the bear, and that all visitors have been moved into safer areas. Kittridge warns him that there will be a full investigation into how a bear was in the park at all, after all of them were supposed to have been re-located into the high country. Kelly tries to contact Arthur Scott (Richard Jaeckel), the naturalist who headed the bear re-location program, but learns that he is out in the field. Kelly calls him in. Meanwhile, as the rangers continue to hunt, Tom and Gail separate, and Gail bathes under a waterfall. But she is not alone… Allison tries without effect to comfort a bitter and depressed Kelly, who exclaims frustratedly that there must be something more that he can do. The following day, Kelly enlists the help of helicopter pilot Don Stober (Andrew Prine). The two go out searching for the bear, and see something that they think might be it…but which turns out to be Scott, disguised in a deer-skin. Scott tells them excitedly that the animal they are looking for is an enormous grizzly bear. Kelly and Stober scoff, but Scott insists that on the evidence of its claw marks and footprints, the bear is of almost prehistoric proportions, fifteen feet long and over two thousand pounds in weight. The three men board Stober’s helicopter and head back. That night, a woman camper is attacked in her tent and killed. Kittridge abuses Kelly and Scott, brushing aside Scott’s assertion that the animal responsible is a grizzly bear. To Kelly’s horror, Kittridge invites in a number of local hunters – amateurs, not professionals – and lets them loose in the woods. One of them gets more than he expected when suddenly, a gigantic bear looms up in front of him…

Comments: Director William Girdler learned a valuable lesson from the experience of making Abby, and the lawsuit that followed that film’s release. It was not, however, a lesson about refraining from ripping off other film-makers’ blockbuster hits; certainly not. It was, rather, how to rip off some other film-maker’s blockbuster hit…and get away with it.

The ridiculous thing about the suit brought by Warners Bros. against Girdler and AIP in the wake of the release of Abby was that the studio had no concern about the points where that film was actually ripping off The Exorcist: the archaeologist-priest, the subliminal imagery, the medical testing sequence, the conflict between demon and priest. All Warners saw was a possession and an exorcism; phenomena that, rather hubristically, the studio decided that it “owned”, much as Universal has always tried to insist it “owns” the names Frankenstein and Dracula.

This attitude had two outcomes: firstly, Warners lost the lawsuits it brought against its copyists, the courts sensibly deciding that the studio had no exclusive right to such material; and secondly, William Girdler learned that you could rip off a film as shamelessly as you liked—just as long as you altered the central premise.

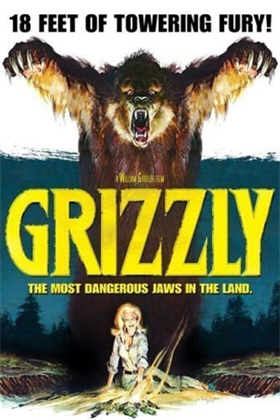

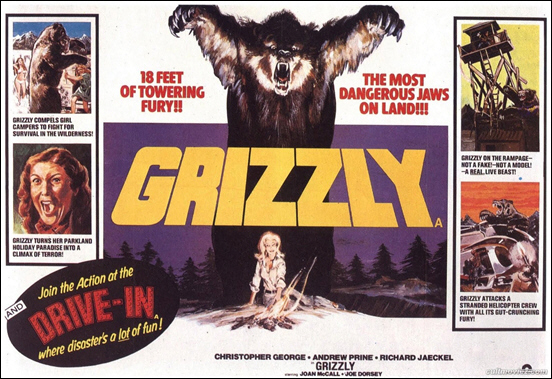

Which brings us to Grizzly, the first, the best and the most blatant of all the many rip-offs of Jaws—and a film that allowed William Girdler to open his eyes very wide, blink them innocently, and say, “But that’s about a shark in the water; this is about a bear in the woods. How could it be the same movie?”

There isn’t much doubt that Grizzly would be a much better film if it wasn’t such a slavish copy of Jaws; almost all of the film’s major weaknesses stem from transplanting plot-points into an environment that can’t support them. On the other hand, there also isn’t much doubt that if Grizzly weren’t such a slavish copy of Jaws, it wouldn’t be nearly so much fun, nor held in the affection that it is—such that many of us chose to ignore the initial, inexpensive (and rather poor quality) DVD release in favour of the subsequent double-disc Collector’s Edition.

Just how slavish a copy is it? – you might be asking. Well, for the time being, we’ll just consider the Big Two.

First off, both films serve up a freakishly large specimen of the killer animal in question, which is occupying a territory that brings it into direct conflict with the local human population, and which begins dining preferentially on Homo sapiens. I’ve always objected to the exaggeration of the shark in Jaws – what, a ten or twelve foot great white shark, a shark twice as long as you are tall, isn’t scary enough!? – and I make a similar objection here: what, an eight foot, 800 pound grizzly bear isn’t scary enough!?

The answer in both cases is, apparently, no. But whereas Jaws went with a model shark, and could therefore pick and choose the animal’s size, Grizzly attempts to realise its killer bear by using a combination of a real bear – a normal sized critter dubbed “Teddy” – footage of a black bear, a fake paw, a malfunctioning model bear (presumably that Jaws homage wasn’t intended), and a guy in a bear suit; and the film’s utter inability to match these disparate elements, or to reconcile what we see onscreen with the verbal promises of the dialogue (not to mention the film’s advertising art) is both jarring and hilarious.

And second, there’s The Triumvirate. Much of Jaws’ greatness has nothing to do with its shark, but instead springs from the three immaculate central performances from Roy Scheider, Robert Shaw and Richard Dreyfuss; from the characters that those men created, and the dynamic between them. Grizzly also has a central trio of bear-hunters; and while Christopher George, Andrew Prine and Richard Jaeckel may not be Scheider, Shaw and Dreyfuss, they are three solid, professional actors who interact in a way that suggests that they enjoyed this shoot, and who do their best to put this thing over…and to pretend that we haven’t all seen this film before under another name.

Christopher George gets the short end of the stick here, chiefly because his situation as Martin Brody’s stand-in forces him both to be mostly passive during the hunt for the bear, and also into a wholly unnecessary relationship with photographer Allison Corwin; their exchanges stop the film dead in its tracks.

Eyewitness estimates are notoriously unreliable…

Andrew Prine is better treated as the Quint substitute, being allowed simply to project his own rather likeable good-ol’-boy personality; while for mine the film is stolen by its Matt Hooper, Richard Jaeckel as the thoroughly eccentric Arthur Scott, who likes to dress up in deer-skins and live with the animals he tracks, and who, when begging for permission to locate the bear himself, claims, “Hell, I can look like him; I can smell like him!” And yet Kelly and Stober keep getting into confined spaces with him. Remarkable.

To be fair to Grizzly, this demarcation isn’t as clear as I’ve made it sound: Stober and Scott swap certain aspects of their models, and Stober’s time in the military has had a very different impact upon him than did Quint’s upon him; but in the broad sense the copying is as usual fairly shameless.

These are the two that leap out at us, but there are plenty of other Jaws riffs here; the rest are better dealt with in context.

Before I start on the film proper, however, there is one observation I’d like to make. Watching this film again, along with a bunch of others of the same vintage, I am reminded of just what a mean-spirited decade the seventies was. Now, it may not sound like it, but I don’t mean that as a criticism. I’m far more critical of the implications of the so-called “torture porn” subgenre of film-making, which as much as anything acts as a measure of what a sadly jaded bunch we have become; senseless, in the original meaning of that term; unmoved by anything short of graphic suffering and dismemberment.

Terrible things happened to people in films of the seventies, too, but there is less of a sense that the people staging those scenes were getting their jollies by doing so, and more that they were simply telling it as it is. The world had lived through an awful lot over the preceding decade or so – was still living through it – and many of the films emanating from that period in history illustrate the fact that it was a time when people truly did understand that, well, shit happens; that it happens a lot.

I am officially in love with whoever designed this…

The most criticised scene in Grizzly sees a small boy having his leg torn off by the bear. Now, doubtless, that scene is there purely because of its counterpart in Jaws, the death of Alex Kintner; in that respect, the scene is indeed an exercise in cynicism. But it’s worth noting that William Girdler backs off as Steven Spielberg did not: the boy survives the attack, improbable though that is. Girdler had, clearly, reached his personal limit.

(Moreover, this digital age offers another defence of William Girdler. The clarity of the DVD, and a good pause button, makes the real leg behind the bloody prosthetic clear in the aftermath shot of the attack on the boy; while when “Bobby” is attacked in the first place – by the guy in the suit – there’s a quick flash of his face that demonstrates irrefutably that Brian Robinson was having the time of his young life.)

One of Grizzly’s enduring mysteries is where, exactly, it is supposed to be set. The film was shot around Clayton, Georgia, which is not, to put it mildly, the heart of grizzly bear territory. As I understand it, the grizzly is – and was – confined to the northwest of the United States: Washington, Montana, Idaho and of course Wyoming; although there have been unsubstantiated reports of them as far east as Colorado. So while the film was probably shot in Black Rock Mountain Park, it remains discreet about its geography, only ever referring to “the park”.

The film opens with a helicopter flight over some lovely scenery, with Don Stober lecturing a “senator” and his unidentified companion about the necessity of conserving the area from further human encroachment. This sequence turns out to have nothing to do with anything, but it is very pretty. (It is also accompanied by some wonderfully inappropriate “pastoral” music, played by no-one less than the London Philharmonic Orchestra. I’ve always wondered if they knew what their music was destined for.) The shooting of Grizzly went from November into December; the many the aerial shots were captured before principal photography began, in order to make things look more autumn-y, and to justify the huge numbers of visitors still populating the park.

Bearhugs!

And so begins the story proper, as head ranger Michael Kelly holds a briefing. One minor point where Grizzly differs from its model is in delaying the first attack scene. Here we get Kelly deploying his limited troops so as to take the best care possible of the park’s unwontedly high number of visitors, and we are introduced to Ranger Tom and Ranger Gail, who make goo-goo eyes at each other. Apparently neither of them has ever seen a killer animal film before.

We cut to two young women up in the highlands somewhere, whose names are actually Margaret and June, but who tend to be known amongst devotees of this film simply as “Red-Shirt” and “Pink-Shirt”. (Why? Well, for one thing, there’s clearly no point in getting attached to these two. For another—well, you know…) The two return from a hike to their campsite groaning that they “must have walked ten miles”; and even someone as fundamentally urban as I am is compelled to blink in disbelief: not only are they carrying no supplies of any kind, like maps, or compasses, or above all water bottles, but the whole time they were away, they left their campfire burning!?

A false scare follows, as Ranger Tom appears on horseback, checking on their plans and reminding them to report at the ranger station when they get down. Red-Shirt then starts cleaning up, while Pink-Shirt seizes a roll of toilet paper and (thankfully) heads off camera, commenting, “I’ll be right back”.

After that, they thought they were going to survive?

One of the real weaknesses of Grizzly, as intimated, is its presentation of the bear. Let’s face it: you just can’t hide a bear the way you can a shark; so to get around this problem, William Girdler relied on a variety of techniques, including a ubiquitous but wildly inconsistent POV shot. It’s true that bears can stand on their hind-legs, and often sit on their haunches; but this film has its bear walking around on two legs.

Not a fake! Not a model! Well…not a model…

A normal male grizzly is six or seven feet long, and weighs anywhere between 400 and 800 pounds. Arthur Scott puts this animal’s length / height at fifteen feet; the ads waver between fifteen and eighteen; and some of the POVs have it easily at twenty; while its weight is estimated at around 2000 pounds! The end-of-film revelation of a normal-sized grizzly is therefore wonderfully deflating.

This is also an incredibly noisy bear, the POV shots invariably being accompanied by much growling and snorting and snuffling. All of which just adds to the hilarity when, after reacting violently to the soft sounds of Ranger Tom’s approach, Red-Shirt remains oblivious as a fifteen-foot, two thousand pound, loudly snorting grizzly bear closes in on her…

The Media Blasters/Shriek Show DVD of Grizzly restores all the bloodshed often cut from earlier releases, and Red-Shirt feels the full brunt of this non-censorship policy as her arm goes flying off into the distance. We get more POV shots as she is bloodily slapped around, and finally collapses. At that inopportune moment, Pink-Shirt – also, it seems, suffering from Selective Deafness – wanders back. She takes one look, turns, and runs, stumbling across an old wooden shack. She shuts herself in, but the bear immediately commits the first of its two demonstrations of contempt for human workmanship by ripping open the cottage—and then Pink-Shirt.

(One of the most persistent of all urban myths is that somewhere in Grizzly is to be found Susan Backlinie. My feeling is that this stems from a combination of two things: the understandable expectation that she would be in this film – given everything else, her absence is certainly its biggest surprise – and confusion arising from Ms Backlinie’s involvement in the previous year’s The Grizzly And The Treasure. For years it was believed, incorrectly, that she was either Red-Shirt or Pink-Shirt; while rumour continues to insist that scenes with her were filmed but then cut—but why on earth would Girdler have done that? In any case, if Ms Backlinie had been in Grizzly, she would certainly have been playing Ranger Gail, for reasons that shall soon become obvious…)

“June? Is that you? Or is it a fifteen-foot, two-thousand-pound grizzly bear?”

And then, after the bloody slaughter of two human beings, we learn what true horror is, as we watch the interaction of Michael Kelly and Allison Corwin.

In Jaws, the relationship between the Brodys was pivotal to the delineation of Martin Brody’s character. Here, Allison is entirely superfluous to the story, and every wince-inducing moment confirms it: the banter between Kelly and Allison is arch and laboured and contributes nothing but pain. BUT— Brody had a wife, so Kelly has to have a girlfriend.

(Oh, yeah, right; almost forgot! Even as there is a union rule that forbids reviewing of the original Amityville Horror without referencing Stephen King’s Danse Macabre, so too is there a rule that no-one can review Grizzly without paying out on Joan McCall for her hair-do. This is one instance when I am firmly on the side of the mob: it’s awful.)

For the record, Allison is a photographer who is supposed to be documenting the change of seasons in the park, but is spending more time fussing over the business practices of her father, who owns a guest lodge there. (I love her specific complaint: that her father doesn’t mark up his booze prices enough!) Kelly interrupts and carts her off, and some time – and much teeth-clenchingly bad dialogue – later, the two run into Ranger Tom, who’s worried about the two young women he spoke to earlier, who have not reported in as they promised they would.

The three go looking, and Kelly inspects the cabin…only to find Pink-Shirt’s bloody corpse when it falls from the rafters. Eh? I thought bears buried their leftovers, not stuck them up trees!? Or wherever. A full-scale search is then instituted, which goes on until after dark; and we get the film’s one effective Allison moment as she literally stumbles over Red-Shirt’s remains, ending up wrist-deep in them. Ewww!!

Sometimes the jokes just write themselves…

Cut to a hospital. Oh, goody! – a gruesome coroner’s scene! Haven’t seen one of those since, ooh, let me think… There’s no disagreement this time, though: the doctor (played by Charles Kissinger, who also played the doctor in Abby) simply confirms the cause of death, going on to suggest that the victims got between a mother bear and her cub—this being (as the script doesn’t make clear) the scenario most likely to result in a fatal bear attack. Kelly isn’t convinced. “Bears don’t eat people!” he protests. “This one did,” replies the doctor helpfully.

Enter my favourite character in the film, Park Supervisor Charles Kittridge, fuming over Kelly’s failure to alert him personally to the double tragedy. Kittridge is, of course, our stand-in for Murray Hamilton’s Mayor Larry Vaughn. It is common for reviewers – including Yours Truly – to dump a lot of crap on Larry Vaughn; but if it is true that his behaviour isn’t particularly admirable, neither is there a moment when you don’t understand the motivation for it. Closing the beaches in Amity, a “summer town” that lives for nine months off the proceeds of the other three, would indeed cause enormous damage to the local economy. Similarly, closing the park here would…

Um…

Yeah.

Oh, dear…poor Joe Dorsey! As I’ve said before, Grizzly’s most egregious dramatic stumbles are due to its absolute determination to copy Jaws no matter what, and nowhere is that more evident than in the behaviour of Charley Kittridge, and his refusal to “close the park”. The best thing about this plot point is that the film goes out of its way to highlight its own idiocy: not only is the peak season for visitors already over, they tell us so – twice – in the opening scenes! “This is the largest post-season crowd we’ve ever had,” announces Kelly, while Walter Corwin comments, “The season may be over, but…”

“This was no camping accident!”

During this part of the film, I always get a clear mental image of William Girdler calling his cast and crew together and addressing them, possibly through a megaphone, with the line, “Okay, listen up: can anyone here think of a reason why they wouldn’t just close the park? Anyone??” Can’t you just picture the silence? – the head-shaking? – the embarrassed twisting of toes into the ground that followed?

But of course, Girdler went ahead anyway—and marvellously, the film barely bothers to pretend in the end that there is a reason why the park can’t be closed: certainly the explanation that Kelly finally comes up with would have been better left unuttered. But we shall deal with that anon.

So, the first of many clashes between Kelly and Kittridge follows, and we get something akin to plot—gasp! We learn here that all of the bears in the park were tagged and relocated to “the high country”, under the direction of naturalist Arthur Scott who, Kelly later explains to Allison, “Knows every bear in the park personally”. Allrighty, then, concludes Kittridge, it’s all Scott’s fault; he orders Kelly to bring him in.

From here we cut to an hilarious sequence of campers – dozens of them – literally stampeding downhill as a panicked mob, as a voiceover (a radio?) announces the deaths of the first two victims. Meanwhile, Kelly tries to contact Scott, who is “in the field”, and finally does, the noise frightening away the family of deer that Scott has been “living with” and earning his wrath.

Kelly tells Scott about the fatalities, and we get an oddly out-of-place “educate the audience” moment here as he adds disbelievingly, “It buried the remains!” Scott explains to Mr Head Ranger that, yes, that’s what bears do, before agreeing to “come back in”.

Quint. Stober. Hooper. Scott. Brody. Kelly.

Meanwhile, all the other rangers are out hunting the bear. At the foot of a waterfall that evidently marks the limit of the area they’re supposed to be searching, Ranger Gail foolishly voices the opinion that, “One thing’s for sure: he isn’t around here.” She then gratefully accepts Ranger Tom’s suggestion that she stay behind while he climbs up a ridge ahead and looks around. “I’m going to soak my feet in the stream,” she announces.

Much to the surprise of everyone not conversant with exploitation films, “I’m going to soak my feet” turns out to be Ranger-Speak for, “I’m going to strip down to my scanties and shower under the waterfall”. And as Gail makes her way through the cascading water, the POV suddenly shifts…and starts growling.

Thinking about the death of Ranger Gail, you can only shake your head in mystification. As she showers, the bear’s enormous paw suddenly appears in shot, rising up from beneath and to the right of her, covering her body and grasping her left shoulder…which means that not only must the bear have managed to get under the waterfall without Gail seeing it (or hearing it), but given the angle of the attack and the size of the animal, it has to be lying on its back…if indeed she isn’t standing on it!!

Anyhoo— Ranger Gail screams, and the water goes all bloody…

Fade to that night, and Kelly getting good and smashed while Allison attempts some peculiar reverse-psychology comforting. (He: “There’s something I’m not doing!” She: “Sure, you’re not killing the bear.”) Kelly ultimately decides that the “something” he ought to do is the recruitment of Don Stober, who fills in for Quint by supplying a helicopter instead of a boat.

The two go out bear-spotting, and do spot something… It’s Arthur Scott, crawling through the underbrush in his camouflage deer-skins; and when the others set down, he has a few interesting facts to impart to them about their ursine quarry. When Don Stober asks him scornfully what he would have done if he had caught up with “that big brown bear”, Scott retorts that it isn’t a brown: it’s a grizzly, and not just any grizzly, but a fifteen-foot, two-thousand-pound monster.

Well, yes, I guess technically she is “soaking her feet”…

Kelly and Stober are understandably sceptical about this, causing Scott to make the film’s most eyebrow-raising suggestion: that the bear is, if not an actual living fossil, then some kind of throwback to an ancestral bear, “Arctotis ursus horribilis.”

Ah, well. Jaws certainly propagated a lot of misinformation about the great white shark – and did incalculable damage to the species thereby – so Girdler probably felt he had a perfect right to tell as many fibs as he liked about the grizzly. To be frank, bear biology isn’t one of my strong suits, so it’s quite possible that I have some of the following details wrong. If so, I’m happy to be corrected.

As I understand it, the problem here starts with Scott’s assertion that, “It isn’t a big brown, it’s a grizzly.” A grizzly is a brown: one of the recognised subspecies of the brown bear; and all brown bears in the United States are grizzlies. Moreover, all brown bears are correctly Ursus arctus, while the mainland grizzly – as distinguished from the Kodiak bear, another recognised subspecies – is Ursus arctus horribilis—which I assume is what was intended by Scott’s garbled, “Arctotis ursus horribilis”.

In short—Arthur’s Scott’s speech about bears contains more lies than anything I’ve seen since the opening crawl of Anaconda.

Also, “Arctotis” is a genus of flowering plant. From South Africa.

Had Girdler settled for an ordinary grizzly bear, most of this could have been avoided. However, post-Jaws, I guess that was out of the question. But why this nonsense about “the Pleistocene era”? My guess is that, at an inconvenient moment in the production, someone had the temerity to open a book…and discovered that grizzlies are omnivores with a predominantly herbivorous diet, which they supplement with carrion. They also eat a great many insects, and fish when they can get it; they kill other mammals only occasionally, and even then, although they can kill a moose, they usually feed either on much smaller species, or on the young of larger animals like deer.

“Really, it’s a miracle of evolution! All it does is walk and eat and crap in the woods!”

(Kodiak bears, and grizzlies living in the coastal regions of Alaska, do consume a great deal of fish; it is this high-protein, high-fat diet that accounts for their larger size.)

None of this was what William Girdler wanted to hear, of course, hence, “Arctotis ursus horribilis.” These, ahem, ancestral bears are further described by Scott as, “Strictly carnivores, those things; they sure do love meat”. Mwoo-ha-ha!

It falls to Don Stober to ask the obvious question: “What the hell’s a million year old grizzly doing here!?” – a question the film never attempts to answer.

Anyway, justifiable scepticism notwithstanding, Stober and Kelly give Scott a ride down to the park headquarters.

That night, we visit with an astonishingly large group of campers. All those panicky hikers stampeding downhill earlier on must have stopped when they hit bottom; that, or the authorities of Amity were mistaken about the effect of killer animals on the tourist trade. (Which, by the way, has always been my sneaking suspicion.) As most of the campers sing “We Are Working On The Railroad” (?), one of them, a woman, goes into her tent to slip into something more comfortable – a voluminous flannel nightie; no, really – and to apply perfume, while her husband licks his chops in anticipation.

However, whether it’s the nightie or the perfume that’s the problem, I don’t know – I’m guessing the former – but the bear ignores all those dozens of campers sitting so temptingly out in open, and instead rips the back off the woman’s tent. In the film’s most bizarre death scene – if we overlook the logistics of Ranger Gail’s, that is – the woman is swung around with her hair pointing straight up. Obviously, this kill scene was filmed with the victim lying over the edge of a bunk; and then William Girdler, for reasons known only to himself, inverted the footage. Don’t ask me.

Grizzly: a hair-raising cinematic experience!

(C’mon, gimme a break: I didn’t use one “unbearable” joke!)

Kelly and Scott are soon afterwards on the scene, and in one of my favourite throwaway moments, a ranger tells the milling campers, “Go back to your campsites”…and they do!? After a fatal bear attack!!?? Honestly, I haven’t seen such an obedient and unquestioning mob since the sheriff in Night Of The Lepus told the people at the drive-in that there was a herd of killer rabbits heading their way, and not one of them batted an eye-lid.

All this leads to yet another of the many shouting matches between Kelly and Kittridge, during which Kittridge waves aside Scott’s assertion that they are not dealing with an overlooked or a back-in-town local bear. “There is no grizzly!” he insists, suggesting that he’s been taking lessons in animal management from Michael Caine.

Kelly demands “men from Washington” – State or D.C., it isn’t clear – but Kittridge, not wanting things “blown out of proportion”, retorts that Kelly already has enough men, setting up a confusing segue to another cherished cliché, the “idiots on the loose” sequence, as whooping hunters pour into the park at Kittridge’s behest. One of them encounters our killer POV shot; we also see some real live bear feet (black ones, though), and are given our first, very brief, look at a real live whole bear shortly after.

The hunter, meanwhile, takes one look at what is supposed to be a freakishly large grizzly and drops his gun. That’s my kind of hunter! He then sprints off through the woods as the paws and the POV shot follow, and escapes safely when he falls down a river bank into the water and gets swept away.

Still more Kittridge / Kelly / Scott brawling follows, including what is perhaps the highlight amongst many in this film, as Kelly demands to know why Kittridge is “on my ass”.

Wait a minute… He already has a dark brown plastic office!

“I’m glad you asked,” responds Kittridge—as are we all, once we hear his explanation:

Kittridge: “Kelly, you’re a maverick. We don’t have room for mavericks.”

You know… I don’t generally consider myself to be lacking in imagination; yet I am entirely unable to envisage what being a maverick park ranger might entail.

Outside, Ranger Tom, sitting moodily in his car, reports about the hunter that got away. More Kelly / Allison stuff follows – ugh! – but that’s pretty much the last of it, and almost the last we see of Allison.

Out in the woods, some of the hunters have a close encounter with what turns out to be a half-grown bear cub (a black bear, by the way) and get the bright idea to use it as bait. Unfortunately for the cub, the plan works perfectly.

(We might get graphic shots of people having their arms and legs torn off here, but the cub’s demise is rendered with a discreet fade-to-black.)

Kelly & Co. catch up with the abashed hunters, who offer their services, and Scott points out that the cub’s fate proves that their bear is a male, which should also mean that they can predict his territorial movements. (And yet again, no-one stops to ask the $64,000 question: if all the normal bears have been relocated, where, exactly, did that cub come from??) Kelly devises a trap, wherein the hunters go up a slope and make a lot of noise in an effort to drive the bear down towards him and his men. Ranger Tom is assigned to a lookout tower. He resents this, commenting sarcastically, “Don’t do me any favours!”

Oh, don’t worry, Tom…he isn’t.

Ursus arctus erectus

Kelly, Stober and Scott hunker down in their chosen position, and Scott announces the inevitable: he wants to capture the bear, not kill it. He tries to explain that he has developed a new tranquiliser shell, but Stober scornfully insists that the bullet – and I quote – “Won’t penetrate the hair on his chinny-chin-chin”, and that Scott will probably end up as the bear’s breakfast. Scott argues that now, after the bear has eaten, is the time to act, and Stober replies that this bear has tasted human flesh – “And he ain’t gunna settle for nothin’ less.”

I tell you…second only to my annoyance at science fiction films that blithely – and blindly – insist that Homo sapiens is the bestest, most fantabulous species in the whole universe, just ’cause, come films that insist that once animals have tasted human flesh, it will simply ruin them for anything else. Here’s a newsflash: animals that eat people don’t do it because we taste so damn good. They do it because we’re weak. They do it because we’re soft. They do it because it’s easy. Accept it.

And then—

In Jaws, Robert Shaw’s Indianapolis speech is chilling and unforgettable. In Grizzly, the equivalent scene – you just knew there’d be one, didn’t you? – is one of limitless hilarity. When Scott challenges Stober about the dietary habits of grizzlies, he retaliates with a terrifying tale of a village of Indians, all of whom were slaughtered by…a whole herd of man-eating grizzlies.

A herd.

Of grizzly bears.

“And the other day I saw this weird cloud! A cloud in the shape of a killer bear!”

If nothing else, this scene proves that Arthur Scott is lot more polite than I am, since he doesn’t respond by shrieking with uncontrollable laughter at the thought of a herd of man-eating grizzly bears, as I always do, but rather confines himself to the exquisite understatement of, “That’s pretty hard to believe.”

“Unless,” says Stober grimly. “…you happened to be one of them Indians.”

There is – understandably – a pregnant silence here, and then Scott simply reverts to the topic under discussion before that remarkable interjection. This conversation degenerates into a verbal brawl, with Scott and Stober cracking wise about each other’s mamas. Honestly. Kelly breaks it up, telling Scott he can have first shot at the bear but is not to go off on his own.

Now, in Jaws, the shark destroys a jetty, allowing Spielberg to intimate the animal’s size and power. Girdler therefore had to find something equivalent for his bear to destroy, which is just too bad for Ranger Tom, perched up in his wooden observation tower. Ranger Tom keeps watch with binoculars, looking north, looking south, looking right, looking left, looking up…and then looking down; right down; at the foot of his tower.

Really, the only way this could be any funnier is if Ranger Tom were looking through the wrong end of his binoculars. This is our first lengthy look at Teddy the Bear, and—well, Arctotis ursus horribilis, my ass! Anyway, the bear yet again expresses his disapproval of modern architecture, and the tower – and Tom – come crashing down.

Kelly and Stober come huffing up the hill just too late, as usual, and find Tom’s body. As Kelly gazes mournfully into the distance, Stober makes the gesture of searching for Tom’s pulse. Needless to say, he doesn’t find it…but that might be because of the leather gloves he’s wearing.

Ranger Tom: Grizzly’s equivalent of a Sunday roast.

Back in town, the media are gathering, including Grizzly’s writer-producer Harvey Flaxman enjoying himself hugely by doing his impression of Peter Benchley, and playing a reporter who interviews a local.

Kelly tries to convince Kittridge that he has a plan to find the bear, and asks for men and time and – duh-dum – for Kittridge to close the park.

“There’s no need to close the park,” replies Kittridge – beeeee-causse?? – and in answer to Kelly’s complaints about the growing media circus, he reveals that he invited them, so that everyone could see, “What a clean, thorough job we’re capable of doing”.

Well, if he means a clean and thorough job of eliminating every park ranger in the vicinity, I guess he’s right. Anyway, Kelly has a blinding flask of revelation:

“I just figured you out! You don’t give a good goddamn whether we catch the grizzly or not! – as long as you get your press, so you can go to Washington, and get one of those nice dark brown plastic offices!!”

Tragically, Kittridge here fails to crack like the villain in an episode of Murder, She Wrote – “Yes, I did it! I did it all! For the nice dark brown plastic office!!” Instead, he gives Kelly the sack: “You are gone! Dismissed! Removed!” Kelly subsequently takes no notice whatsoever of this, but then, neither does Kittridge, so I guess that’s okay.

And then it’s time for Alex Kintner, I mean adorable little Bobby, to traumatise a generation. A snorting POV shot creeps ever closer as Bobby plays with his pet rabbit, and then we get a confusing flurry of Teddy’s face, some black bear feet, and a guy in a dark-coloured bear suit. Long story short, Bobby loses his leg – while being clutched to the bear’s chest; hmm – and his mother is killed.

Wait, the surgical tiger is native to Georgia!?

This happens in broad daylight. It’s night before we see Bobby being carted off to hospital, and yet he’s still with us. Tough kid. Kelly gets to lay a guilt trip on everyone in the vicinity, including the reporter – “You and your cameras! You made it so exciting! So attractive!” – and Charley Kittridge – “It’s a story about greed! And going to Washington!” And getting a nice dark brown plastic office! Of course, what gets lost in the shuffle here is that, clearly, Bobby and his mother are – were – residents; closing the park wouldn’t have done them a damn bit of good.

In fact, what would have worked was a scenario in which the park was closed, but then the bear, deprived of victims, came into town looking for a new food source. But somehow I don’t think Harvey Flaxman and David Sheldon were really trying for dramatic complexity here.

Then we see Kelly and Stober loading the chopper with guns and a rocket-launcher (!!!!); and Stober starts reminiscing about his ’Nam experiences and how now he don’t kill nothin’ no more, not even flies. (Yeah, except that he was the one who responded to the thought of the hunters killing everything in the park with a big fat who cares?) Kelly reveals that Scott went out on his own after all, and Stober responds with a masterly piece of understatement of his own: “That boy’s weird.”

Kelly and Stober lay a trap for the bear with a gutted deer – which looks a little too real for my liking – and it almost works, except that bright spark Kelly cocks his rifle at the critical moment.

The bear hears and takes off, with Kelly and Stober chasing it. (Oh, yeah, they’re really gunna catch it on foot!) This sequence contains numerous lingering shots of what is absolutely not a fifteen-foot, two-thousand-pound grizzly; in fact, you’d be hard pressed to string together six more inaccurate words. Panting and exhausted, the chasers eventually give up—only to find, when they get back to their trap, that having led them away on a wild bear chase, their quarry simply circled back and helped himself to a tasty snack of gutted deer. Zing!

“Just our luck: he’s smarter than the average bear!”

Scott, out on horseback – uh, that’s “looking like a bear, and smelling like a bear”? – finds what’s left of the deer. He radios the others with a plan: he’s going to rope the remains and drag them towards Kelly and Stober, in the hope of drawing the bear into another trap. Kelly protests, but Scott hangs up and goes ahead anyway.

And he finds the bear, all right, but it isn’t following him: it’s right up ahead.

The inability of the people in this film to spot a fifteen-foot, two-thousand-pound grizzly bear even when it’s standing right in front of them is one thing. What really worries me is the thought of a horse equally oblivious. Anyway, the nag gets its reward when the grizzly strikes out and decapitates it with one blow…pretty good, considering it didn’t manage that with any of its human victims. The horse, remarkably enough, remains on its feet for several seconds after this, before finally staggering and falling; even more remarkably, although we get a glimpse of its “head” flying off, when the horse hits the ground, its head appears to still be in place. Hmm.

And of course, Scott falls too, dropping his gun and being left at the bear’s mercy…

…but that’s not the last of Arthur Scott. The bear, having just eaten most of a deer, isn’t hungry; so it buries its bloodied victim for later, as bears do.

Slowly and painfully, Scott’s eyelids start to flutter. Slowly and painfully, he drags himself out of his shallow grave. He staggers to his feet…and then a roar comes from behind him…

Guess what? It’s now “later”…

Richard Jaeckel contemplates where a career in exploitation film can take you…

And it was this scene, this fate, not adorable little Bobby’s, that drew from me a wail of mingled dismay and admiration the first time I ever saw this film—and not just because I’ve got a soft spot for Richard Jaeckel. This sequence seems to me almost to define its decade; it’s a real seventies shit happens moment. It is also the one thoroughly original scene in the film, the one that has no equivalent in its model.

Kelly and Stober find Scott’s body—again, intact. For all the ghoulish dwelling on the bear’s taste for human flesh, he has conspicuously eaten only one of his eight victims. So I guess he’s that other kind of eee-vil animal, the kind that kills humans just for kicks. Mwoo-ha-ha! (I particularly enjoy the fact that the bear goes to all the trouble of knocking down an observation tower, and then doesn’t bother to eat his victim!)

Kelly mourns, and Stober gets this look like he really wishes he hadn’t said that about Scott’s mother. Later, flying away and planning their next move, or rather the bear’s, the two just happen to spot their quarry, countless miles away from its last kill and walking on two legs. (And if you think those two facts are incompatible, give yourself a gold star.) They pursue it until they judge it to be almost exhausted, then set down in a clearing.

And then the bear attacks the helicopter!!

And in all sincerity, this is an historic scene – because, or so it seems to me, this – THIS – was the very beginning of the action film obsession with the helicopter. Honestly, has there been an action film made since the mid-seventies that didn’t feature the destruction of a helicopter? Off the top of my head, I can’t think of one. In any case, all I know is that in my household, whenever a helicopter appears in such a film, it provokes a knowing and unanimous cry of, “Ohhhhhhhh, no!!”

We’re gunna need a bigger tricycle…

And if Grizzly was the beginning, surely the next really prominent cinematic helicopter was the one in – Jaws 2!? – which I like to think was a sign that someone at Universal Studios had enough objectivity, and enough of a sense of humour, to appreciate William Girdler’s chutzpah.

(All joking aside… I also have to acknowledge here a terrible and tragic irony: that only two years after this, William Girdler would himself be killed in a helicopter crash, while scouting locations in the Philippines. We lost a friend that day.)

Anyway, this scene is not just historically important: it also gives us a fleeting glimpse of the rattiest, tattiest bear suit ever to disgrace a motion picture screen. The helicopter spins wildly, and Stober is thrown out. The bear continues to attack the helicopter, until Stober gets its attention by shooting at it—except there are only two bullets in his rifle. Oh, good one, Don!

The bear heads for Stober (and as it does so, Girdler has the nerve to attempt the “pull-away-zoom” that Spielberg uses during the attack on Alex Kintner), who wields his rifle butt like a club, Kelly jumps out of the chopper and also starts firing. The bear prefers his initial choice of victim, however; and Stober is hugged to death by the ratty, tatty bear suit. How embarrassing!

And then the bear turns its attention to Kelly, who drops his gun and goes for the rocket-launcher. The bear closes in, Kelly fumbles with the unfamiliar weapon, the suspense builds [*cough*], and then….

KERRRRR–BLAMMO!!!!!!

It’s a little known fact that the grizzly bear is highly combustible.

“Look happy, you male offspring of a canine!”

(And, by the way, I also like to think that the climax of Jaws: The Revenge was influenced by this.)

But it’s hardly a cheerful ending, even if you aren’t on the bear’s side. Kelly contemplates his handiwork, then walks over and kneels by Stober. We only get a long shot on this, so I suppose it’s possible that Stober isn’t dead. But then, this was the seventies and, well, shit happened.

When Grizzly hit movie screens it was an immediate and hugely profitable success, in spite of critical scorn—just like Abby. Unlike Abby, however, Grizzly stayed the distance, going on to become the most profitable independent production of all time, until Halloween took its crown away two years later.

The degree of Grizzly’s success is a little difficult to understand. Don’t get me wrong, I adore Grizzly…but I have a hard time imagining that cinema-goers in general share the obsessions that endear this film to me. Perhaps what we have here is a reminder of how different things used to be; that there was a time when, if you wanted to see Jaws again, you couldn’t just put on a video or a DVD (or our local cable, which a while back seemed to be playing Jaws about every ten minutes; not that I’m complaining, mind you), but instead had to settle for watching a blatant Jaws rip-off.

And there was another similarity between Abby and Jaws: namely, that the film’s financial success did William Girdler no good whatsoever. Grizzly was distributed by Film Ventures International (ironically enough, Girdler probably agreed to get involved with FVI because, unlike AIP, they fought back when Warners sued their Exorcist rip-off); and when the profits started rolling in, company head Edward L. Montoro simply pocketed the lot, claiming (falsely) that Girdler and his people had violated the terms of their contract. A lawsuit followed – irony upon irony – which was eventually settled in the complainants’ favour…but not until after William Girdler’s death.

Ursus arctus inflammabilis

Post-Grizzly, tough times forced Girdler to accept help from a friend: Leslie Nielsen, in whose guest house the director lived for over a year. This friendship also led to two professional collaborations. The first was Project: Kill (a spy thriller that, while it falls outside the jurisdiction of this website, is the subject of a short review over at Et Al.), which also ended up in distribution hell; Girdler just couldn’t take a trick. And the second collaboration— Oh, my friends! – the second…

Want a second opinion of Grizzly? Visit 1000 Misspent Hours – And Counting.

That ought to hold the little SOBs…

LikeLike

Hold us? Goodness, my dear, you’ve spoiled us and then some!

I’m very glad your screenshots and their comments are, as far as I remember, pretty much unaltered from the previous iteration of this review. I enjoy the “Bearhugs!” one just because I swear I can hear that kid’s squealing laughter when I look at it, and we all know how much I love the “imflammabilis” gag. In fact, I feel like very little had to change this go-round for the whole review; a case of getting it right the first time, as it were? This is not an insult, mind you; it would be the height of churlishness for me to bag on you for such a thing in the wake of your recent output.

As far as the bear stuff: First, a quick note; it’s arctos, not arctus. Now, it is correct to say that all grizzlies are brown bears, but all U.S. brown bears are not grizzlies. Ursus arctos currently has three recognized subspecies: the grizzly, horribilis; the coastal brown, gyas; and the Kodiak, middendorffi. It’s mostly a matter of where they live, although grizzlies do have their namesake grey-tipped fur, which the others don’t seem to develop. Grizzlies live in the North American interior, and are the smallest due to a relative lack of protein in their diet. Coastals live…well, duh…and are the ones you usually see in salmon-fishing footage. Kodiaks are limited to a stretch of Alaskan islands, and get the largest due to a seafood-rich diet (not much else available on islands…not that I’d complain). Due to no evidence of nearby oceans, Grizzly would seem to be an accurate title as far as what our bear is*…never mind it being somewhere between three and five times** the size of your average grizzly male. If they’d only called it Kodiak, their monster would’ve only been twice as big, at most!

*It just occurred to me that Yogi Bear would’ve been a grizzly.

**Variation given due to the fact the movie itself can’t decide how big it is.

LikeLike

So this time you did point out my typo!? Fine, I’ll point out yours, Mr Imflammabilis! 😛

Yeah, this one pretty much fell out right the first time. Sometimes I change reviews because material mentioned is better off elsewhere, or because of a better understanding of the film’s place in things, or just because of second thoughts; but this one didn’t need much tweaking.

With the change in font size here I space things out more, which creates a need for more screenshots (Which is where an absurd amount of prep time goes). That wasn’t such a burden this time because as it fell out, it allowed me to include shots of Joe Dorsey, Joan McCall and Harvey Flaxman; I like to get a spectrum of cast shots if circumstances (i.e. jokes) permit. I probably should have included one of Tom Arcuragi up the tower, but I figured we see little enough of the film’s actual bear!

This is a landmark piece, all right: the beginning of ‘inflammabilis’, the beginning of the “Is that you?” running joke, the beginning of the Jaws expys. 😀

LikeLike

I thought it would be okay if it was in the name of science! Hopefully I’m still on the “sweet and classy” list?

Oh, that reminds me: I officially designed that poster up there.

LikeLike

Mmmmmmmm-hmmmmmmm?? (Damn! – can’t do an eyebrow-lift emoji here!)

LikeLike

That’s a shame. I can’t tell if it’s a skeptical eyebrow or a come-hither one, and I’m unsure how to proceed…

LikeLike

Take your best guess (she said, raising her eyebrow AGAIN).

LikeLike

Assuming my “best guess” is the one that’s most likely to be correct, I would have to go with “skeptical”…and I suppose I can’t blame you.

LikeLike

Tsk, tsk. You left out a word in your insult. It should be, “You male offspring of a female canine!”

Other than that, great review.

LikeLike

Ehhhh… I thought about it. 🙂

Thanks!

LikeLike

considering how much trouble my cats cause, why is ‘female feline’ not a bigger insult?

LikeLike

‘Cause it ain’t just the females that cause trouble. (Trust me, I know!)

LikeLike

I’m so excited for the follow-up Girdler review now (and now I’m wondering if it’s the same bear suit)!

Are you planning on including PIRANHA in your JAWS-inspired sojourn? That’s my favorite rip-off, just for the sheer delight of so many character actors (and maybe because I grew up in Texas, near where they filmed it).

As always, an amazingly entertaining review!

LikeLike

Thanks, Tim!

As for what the future holds, I can only offer up my eternal promise / excuse of, “Eventually.”

However, I really do intend to get to the Girdler follow-up in this flurry of related reviews, although it won’t be for a while yet.

Piranha is one of those films so obvious, of course I haven’t got to it. 🙂

LikeLike

You know, I was certain you had reviewed it, long ago. (I know you prefer we not delve into your past, but I had to scratch that particular itch.) Turns out I was wrong…after a fashion.

LikeLike

Ah, yes: I remember it…not well at all, actually.

LikeLike

With the obvious time and effort you put into these reviews, it’s totally understandable that DAY OF THE ANIMALS wouldn’t necessarily be anyone’s top priority, though the Richard Jaeckel connection makes me think of a weird one from 1974 that nobody ever talks about, CHOSEN SURVIVORS… I don’t know if you’re familiar with that one, but the premise is bonkers enough to make it worthwhile… people in a high-tech nuclear survival bunker being attacked by vampire bats and Jackie Cooper. 🙂

LikeLike

On the contrary, Day Of The Animals is (like Piranha) on my so-obvious-it-never-gets-done list! 😀

I’m aware of Chosen Survivors but it’s never come my way.

I did once try to talk the boys into a Richard Jaeckel Roundtable, but they weren’t having any… 😦

LikeLike

Chosen Survivors is worth checking out– beyond Jaeckel, of course. I think it invented the concept of screensavers, weirdly enough, in its concept of a high tech communications center. It’s probably biologically as unsound as the day is long, but as far as killer bats movies go, it takes itself more seriously than I expected, and there’s a lot of footage of the cute little bats’ faces, for what it’s worth.

LikeLike

there’s a lot of footage of the cute little bats’ faces

Sold!

LikeLike

OMG, it’s the “worst death ever” guy from that one ninja flick. Turns out he was an actual actor?

¯\_(ツ)_/¯

LikeLike

I think you’re going to have to be more explicit??

I always thought the worst death ever was in Venom… 😀

LikeLike

My guess is he’s referring to Christopher George’s death scene in Enter the Ninja. “Worst death ever”…he’d have to explain that one; perhaps a reference to a review somewhere on the ‘net?

Worst death ever…my first thought is Short Night of the Glass Dolls. Well, actually, being digested over a thousand years in the Sarlacc would probably win. Of course, my assumption there is it somehow keeps you alive that whole time…

*reminds self he needs to get around to Venom when he has a chance*

LikeLike

Jeez, man…do you watch ANYTHING!? 😀

LikeLike

For a brief while, it was a serious contender to replace “guess I’ll die now” as a reaction gif.

LikeLike

Ah, gotcha! Not worst death, worst acted death. 😀

From the other perspective, given the combined exploitation film resumes of Christopher George, Andrew Prine and Richard Jaeckel, it could have been anything!

LikeLike

I actually watch a lot…but it tends to be stuff you wouldn’t be reviewing, for various reasons.

All right, so I’ve got Dracula lined up for when I have some free time (and am even planning to see the Spanish version at a local theater the night before Halloween for good measure)…looks like I can rent Venom on Prime…hopefully that will satisfy you, my dear?

LikeLike

and am even planning to see the Spanish version at a local theater the night before Halloween

Bonus points! – and a bit more slack for the next time this topic comes up!

And really, seeing Venom is in your own best interest. 😀

LikeLike

“The degree of Grizzly’s success is a little difficult to understand. Don’t get me wrong, I adore Grizzly…but I have a hard time imagining that cinema-goers in general share the obsessions that endear this film to me. Perhaps what we have here is a reminder of how different things used to be; that there was a time when, if you wanted to see Jaws again, you couldn’t just put on a video or a DVD (or our local cable, which a while back seemed to be playing Jaws about every ten minutes; not that I’m complaining, mind you), but instead had to settle for watching a blatant Jaws rip-off.”

I that’s part of it, but I think there’s also an issue of it taking longer for bad word-of-mouth to kill a movie’s momentum back then. I was about 9 when this came out, and although I was’t allowed to see this or Jaws, I had a cousin with more lenient parents who did get to see both movies. He had filled me with stories about how awesome Jaws was, and was really excited to see this, and I was excited to hear about it through him! He fully expected it to be as good, if not better, than Jaws. Needless to say, he was very disappointed! I remember him saying the bear arm (the only part you ever see up close) looked like “a board with fur glued on it”.

This movie was able to coast on the general excitement for killer animal films, and the great posters and ads. With no negative internet buzz to kill the momentum, lots of people went, but few really liked it. Since it featured a bear and not a shark, people didn’t see it as a ripoff the same way they would have had it been a shark. At least, not until they were already in the theater…

LikeLike

But that doesn’t really explain why it went on having success: it was in theatres for quite a long time – certainly long enough for any negative word to get around – and it made enough money for it to be worthwhile its distributor embezzling the profits and skipping the country. Obviously there would have been some disappointment but the ultimate outcome suggests a lot of people enjoyed it too.

LikeLike

Maybe they did! It’s not great, but then again it may have been a fun enough diversion at a time when the stakes were lower. The concept of the summer blockbuster was still in its infancy just a year after Jaws, so maybe it was one of the best choices for people who just wanted to get out of the heat! Were there any other big block busters that summer?

LikeLike

The two big summer films of 1976 were The Omen and All The President’s Men. (Both horror stories, in other words. 😀 )

The Omen was a British co-production and it had a rolling release starting in the UK—where of course it opened on the 6th of June.

The implication that its distributors didn’t have any faith in the latter film is interesting. I guess they might have worried that everyone was sick of that particular story.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Also, on the scientific names of bears, I wonder if they were mangling the name of the Short-Faced Bear, Arctodus sp? They would be about 15 feet tall on hind legs. If you want a prehistoric bear for your killer animal flick, THAT’S your guy!

LikeLike

Ah, yes! As I say, bears aren’t my area of expertise, but now that I look into it, that suggestion makes a lot of sense—thanks!

I can never understand how these things get mangled: it can’t be that hard to write a word down and say it! (Still waiting for a reasonable explanation of Orca orcinus…)

LikeLike

Cool, learned something new today. My thanks, as well!

LikeLike

I recall hearing that most predators think humans smell bad and taste bad. It may be one of our survival traits. We still sometimes get chewed on for various reasons: desperation (no better prey around), opportunity (killed this thing that threatened me or wandered onto my turf, might as well eat some), and, in the case of sharks, curiosity (“what is that?” *chomp* “Huh, whatever it was, it’s not that tasty”).

I have heard that tigers in particular sometimes develop a taste for human flesh; all I can conclude from this is that those particular tigers went, “It smells gross and tastes gross — must be a delicacy!” using the same logic I presume motivates people to eat blue cheese.

LikeLike

The myth I usually hear from those old stories is that predators don’t think of humans as food, but once they have a taste, they don’t want anything else. It’s similar to the belief that once a farm dog has tasted sheep, it has to be put down.

LikeLike

Huh, now I’m reminded of some Inuit horror stories, in which once a human has tasted human flesh, even through accident or trickery, that’s it — they’re going to become a crazed, murdering cannibal. (The Inuit have some seriously gory folktales.)

I can actually see the logic with farm dogs, though I wouldn’t think of it so much as “they’re addicted now” as “they broke their training once, they might do it again”.

LikeLike

and the story is usually that the farmer has to kill the kid’s only friend, his beloved dog. and the sheep killings continue. so the farmer needlessly killed the dog. and the kid is Not Happy.

Saki wrote a story with this plotline, (spoiler alert) and the kids (multiple) kidnap the farmer’s little girl and dangle her over the pigsty for revenge. The farmer has to stand all night with a lit candle for penance.

Best part of the story – Farm says, “I’m really very sorry about your dog”. Kids say, “We’ll be really very sorry about your daughter afterwards too.”

LikeLike

Honestly, how full of yourself do you have to be as a species to think how good you taste is something to brag about?

Anyway, it’s nonsense: we’re nobody’s preferential prey (if the consequences weren’t what they are I’d add, More’s the pity). You get the occasional shark that doesn’t mind supplementing its diet, or a bear that will eat what it kills (rather than killing to eat), but most commonly it happens if a predator such as a lion gets injured and can no longer hunt and kill its usual prey—and like I said, we’re slow and soft.

But of course, if you’re going to keep intruding into a predator’s hunting territory…

Good old Saki! 😀

LikeLike

I wasn’t going to add this, but I just can’t help myself.

There is a large body of works (movies, stories, books) which suggest that human meat is the absolute best-tasting meat ever for humans. The movies of diners and sausage makers, all with that ‘special’ ingredient’, are legion.

I’d really like to know if that were true, but I’m not sure who I would ask without getting myself locked up.

LikeLike

Almost anything else done to the human body you can ask, but yeah, that one’s a bit tricky. 🙂

I think it’s just the far point of the same egotistical argument: we even taste fabulous to ourselves! – although there’s a hint of addiction in there, too, a ‘We couldn’t help ourselves’ excuse.

Speaking of which…all this is making me feel I ought to bump Survive! up the list…

LikeLike

shiftercat says:

October 29, 2019 at 7:28 am

Huh, now I’m reminded of some Inuit horror stories, in which once a human has tasted human flesh, even through accident or trickery, that’s it — they’re going to become a crazed, murdering cannibal. (The Inuit have some seriously gory folktales.)

WENDIGO

LikeLike

The Wendigo is from Algonquian mythology, but yeah, similar! In the Inuit stories there’s no physical transformation, or even an implication of possession by an outside force: it’s just ravenous madness.

It makes sense that stories warning people against cannibalism in the harshest possible terms would be common amongst First Nations peoples, especially Northern tribes. They were living in a harsh landscape and frequently facing starvation; society would quickly fall apart if too many people succumbed to the temptation of eating their neighbours rather than cooperating with them.

LikeLike

I read The Good Earth a while back: the characters have to deal with famine when the crops fail, and it is implied that one couple survives by eating their own daughters; only their daughters, of course…

LikeLike

(Considers obvious points of reproductive biology)

So they’ll be dead in a generation, then.

LikeLike

The Champawat Tiger had been shot in the face by a poacher.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Champawat_Tiger

“No beast so Fierce” about the Tiger and his hunter is a great read.

LikeLike

NPR just mentioned today that Grizzly II is being released for streaming and drive-ins(!)

LikeLike