“All the little devils are proud of hell.”

[Also known as: Outback]

Director: Ted Kotcheff

Starring: Gary Bond, Donald Pleasence, Chips Rafferty, Sylvia Kay, Al Thomas, Jack Thompson, Peter Whittle, John Meillon

Screenplay: Evan Jones and Ted Kotcheff (uncredited), based upon the novel by Kenneth Cook

Synopsis: In the one-room school of the tiny outback town of Tiboonda, teacher John Grant (Gary Bond) counts down the minutes to the end of the school year—his only thought to escape back to Sydney for the Christmas holidays. Packing up his meagre belongings in the room over the pub that is Tiboonda’s only other building, Grant catches the train for Bundanyabba, from where his connecting flight will depart the following morning. With a long night to fill, Grant wanders into the Imperial Hotel, where he immediately attracts the officious attention of policeman Jock Crawford (Chips Rafferty). Seeing no escape, Grant goes along with both Crawford’s cross-questioning and his insistence upon heavy and rapid beer-drinking, explaining bitterly that his presence in Tiboonda is due solely to the $1000 bond which he owes to the Education Department. When Grant finally insists that he must have something to eat, Crawford introduces him into a second bar across the road, ordering him a steak in the kitchen and explaining to him the game of two-up going on in the back room. Watching the swarming mass of men betting their entire salaries upon the toss of two coins, Grant is initially scornful—until he observes the sums of money that are changing hands… Sitting down to his steak, Grant falls into conversation with the erudite yet heavy-drinking Clarence “Doc” Tydon (Donald Pleasence). Tydon defends the behaviour and attitudes of the locals, pointing out how very little there is to do or to even to live for in this remote part of the country. Eventually, Grant drifts back into the two-up room and, bracing himself, begins to bet. Within a ridiculously short time he has tripled his cash holdings. Almost hysterical with joy and relief, he runs back to his hotel room, where he counts his winnings and calculates how much closer he is to discharging his bond. But as he stares down at his money, Grant becomes gripped by an irresistible impulse, which sends him back to the two-up room—where he loses not only his cash but his year’s final paycheque… Waking the next morning to sober recollection of what he has done, Grant goes looking for the local labour exchange, hoping to pick up enough money to pay for his flight to Sydney. However, the exchange is closed until the following Monday. At a loss, Grant wanders back into the pub, where he attracts the friendly notice of Tim Hynes (At Thomas), who buys him several drinks, expresses sympathy for his situation, and finally insists upon inviting him home. There, Grant is introduced to Hynes’ daughter, Janette (Sylvia Kay), who accepts his presence without comment and shrugs off his apology for intruding. Hynes returns to the problem of Grant’s monetary woes, even offering to lend him his fare to Sydney. Embarrassed, Grant refuses—but does accept the drinks that Hynes almost forces upon him… Several long, hot, beer-soaked hours later, Grant and Hynes are woken from an alcohol-induced sleep by the arrival of Dick (Jack Thompson) and Joe (Peter Whittle), two rough-mannered, rowdy young miners who come carrying a supply of beer and initiate yet another lengthy drinking session. Grant tries to excuse himself, but as the puzzled Hynes points out—where is he going to go? With the arrival some hours later of Doc Tydon, the party spirals to another level—and John Grant finds himself trapped inside a nightmare…

Comments: In 1970, after a decade of increasing public pressure, the Australian government took its first tentative step towards the support of a local film industry by establishing the Experimental Film and Television Fund. The immediate beneficiary of this move was Peter Weir, who repaid the investment in his work by scooping all available film-making prizes, and thus reassured the government about the wisdom of its continued investment in th’yarts.

Increased resourcing saw an explosion in Australian film production during the 1970s, with the resulting films tending to fall into one of two widely disparate categories. There were the respectable, prestigious productions, the kind that attracted critical approval and (cringe) could be sold overseas with pride; and then there were those productions that were not respectable, and not prestigious; films that catered to the drive-in market via lashings of sex, violence and general weirdness; films that made bureaucratic blood run cold, at the very thought of the impression they would give if they were sold overseas—those raw, unapologetic and all-too-revelatory films that today get lumped together under the title Ozploitation.

In 1971, while the true local industry was still taking its baby-steps, there was a film produced in Australia that would prove enormously influential upon both branches of subsequent film-making: a film that would both find an audience and win critical acclaim overseas, in particular at the Cannes Film Festival, while at the same time dealing with material so confronting, it makes many of the “Ozploitationers” to follow look tame by comparison.

The novel Wake In Fright was published in 1961. Its author, Kenneth Cook, was a journalist as well as a novelist, and involved at different times in film production and politics. His first novel, written at white-heat in only six weeks, drew upon his own experiences as a radio journalist for the ABC in the late 1950s, a time when radio was still the dominant media form cross-country and, indeed, for many Australians, the only one.

Cook’s job saw him sent into rural and remote districts for months on end. He later admitted that he began his assignment with all sorts of romantic ideas about “the outback”; he came out of it changed forever. Wake In Fright describes the experiences of a young, city-bred schoolteacher, John Grant, who finds himself stranded in the mining-town of Bundanyabba over the course of a weekend, and who ends up taking a nightmarish journey into the depths of his own soul.

The people and the behaviours that Cook describes in his first novel were based upon personal observation—and, perhaps, more than that. It is evident that the character of John Grant is to an extent autobiographical: as the story progresses, the question of just how autobiographical becomes an increasingly unnerving one. At the same time, the book’s title – taken from the medieval curse, May you dream of the devil and wake in fright – becomes less and less metaphorical…

When Wake In Fright was first published, Kenneth Cook was reluctant to talk about it too much; it was close enough to the bone to be all-but, if not outright, libellous. However, the novel was both a critical and a popular success, and in time Cook began to relax and open up about its genesis, revealing that all of his characters were sketches of people he had encountered during his days as a radio journalist. (That’s right, folks: there was a real Doc Tydon. Hold that thought…) He even admitted what had been evident from the start to many who had read the book: that the town of Bundanyabba was based upon Broken Hill, a mining-town in far-west New South Wales, near the border with South Australia. Eventually, evidently reassured that vengeance, neither legal not personal, was pursuing him, Cook described Broken Hill circa 1960 as, “An unimaginable boil of horror.”

Almost from the moment of its publication, there was interest expressed in adapting Wake In Fright for the screen. The book was first published in Britain, and the rights were sold to Dirk Bogarde, who envisaged it as a project for himself and Joseph Losey. Losey in turn gave the task of adapting the novel to Evan Jones, who at that time was becoming one of his regular collaborators (including on The Damned). Jones prepared a screenplay, but the project failed to attract funding and Bogarde’s rights to the novel lapsed.

They were picked up again by Morris West, another Australian novelist and a friend of Kenneth Cook, who began to develop the project through his own production company (NLT, in which he partnered with local entertainment figures Jack Neary, Bobby Limb, and Les Tinker), with funding from Group W, an American production company.

Problems began on the production side almost immediately. Morris West had picked up Wake In Fright purely as a favour to Cook, and no-one in NLT liked the novel or had much idea about what to do with it; while the American side of the deal was even less enthusiastic. Moreover, the first collaboration between NLT and Group W had been a resounding financial flop, and tensions between the two production companies were running high before Wake In Fright even began shooting.

Meanwhile, on the actual film-making side everything was falling into place with extraordinary precision. Evan Jones, who was still attached to the project and whose screenplay was still intended to be the basis of the film, suggested that the job of directing be given to Ted Kotcheff, a Canadian living and working in Britain, with whom he had worked before.

At the time of Wake In Fright’s production there was some discontented muttering over the hiring of so many “foreigners” in what was, initially, hailed as perhaps the first thoroughly Australian film production of the post-war era; though in the long-term, no-one could argue with the results. It does seem strange, however, that Ted Kotcheff apparently never considered an Australian actor for the role of John Grant, instead offering the role to a number of different Brits (including Michael York) before finally casting Gary Bond, who at the time was known chiefly as a stage actor.

On the other hand, for the contentious role of Janette Hynes Kotcheff did interview many Australian actresses before reluctantly concluding that none of them had precisely the qualities he was seeking—and ultimately casting Sylvia Kay, whose hiring he had resisted from the beginning, despite her suitability, on the dual grounds that she was (i) also British, and (ii) his own wife. And in the end, the third important role in the film likewise went to a British actor: Donald Pleasence, who immediately set to work learning how to smother his native accent in an Australian drawl.

In the completed film, of the three it is only Bond who is obviously, immediately English—and this is something that tends to be more jarring now than it would have been at the time of Wake In Fright’s production, when a particular sector of the Australian education system was still priding itself on teaching its students to speak with a “correct” – that is, British – accent. In 1971, John Grant’s way of speaking would have marked him not as English, but as the product of a certain kind of school. Today, though his accent stands out like a sore thumb, it simply positions him as even more of an outsider than his circumstances have already made him, and in no way works against the effectiveness of Gary Bond’s casting.

Overall Wake In Fright is a remarkably faithful adaptation of its source; and, where the two do differ, the film (as even Kenneth Cook admitted) is generally the stronger. Evan Jones and Ted Kotcheff continued to tweak the screenplay all the way through production, with many of those changes drawing upon Kotcheff’s own experiences and reactions during the pre-production location scouting, and the location shooting that followed.

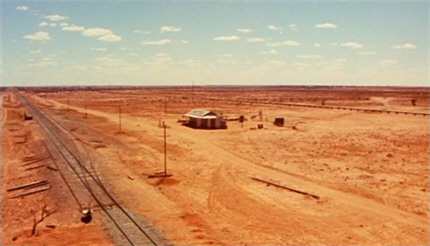

Though all the interior scenes were shot in Sydney (not that you’d know it!), in order to capture a true sense of the isolation of the story’s setting it was agreed early that the exteriors had to be filmed in the real outback. In the end, location filming occurred in the place simultaneously most appropriate and, all things considered, most unlikely: Broken Hill itself, and its environs—where, not a little to their surprise and relief, the cast and crew found themselves on the whole welcomed and assisted.

At the time, Ted Kotcheff countered criticisms of his own hiring by arguing that it was because he was Canadian that he felt he could do a good job on Wake In Fright. Canada and Australia, he reasoned, shared both a colonial past and settlement patterns marked by a handful of cities separated by vast empty spaces—not the same kind of “empty”, granted, but in the same way populated by only small, scattered communities shaped by their isolation and suspicious of outsiders.

Sound as his reasoning may have been, it hardly prepared Ted Kotcheff for the realities of outback Australia, which simultaneously fascinated and terrified him—with this response, in turn, lending a rare power to the production in question. In this respect, Wake In Fright is indeed an example of the cinematic “outsider eye”, wherein a stranger to a place sees differently, and reacts differently, from how a local might; but there is more to it than that here, with the phenomenon of the outsider eye built upon a foundation of intensely personal local knowledge, a unique blending of disparate perspectives.

The novel Wake In Fright is an authentic record of Kenneth Cook’s experiences in Broken Hill, albeit one seen through a fractured prism of loathing and resentment; the film Wake In Fright is Ted Kotcheff looking around in disbelief and saying, “Oh, my God…it’s all true!”

Wake In Fright begins with an astonishing 360o shot, a slow, silent contemplation of Tiboonda and its environs: the one-room school, the pub-cum-motel, the railway platform, with the railway line itself disappearing over the horizon in both directions, and—nothing else, just the red earth stretching as far as the eye can see in all directions. In a single camera-movement, the film manages to capture the terrifying paradox of remote Australia, a place where agoraphobia and claustrophobia collide: an infinite space in which there is nowhere to go.

Inside the school, we find John Grant and his students, who vary in age from six or seven up to their late teens, spending the last hour of the last day before the Christmas holidays in the traditional Australian manner, i.e. pointlessly running down the clock. The students are no more eager to get out of there than Grant himself, however, and after a couple of glances at his watch he dismisses his class early.

There won’t be too many opportunities to say positive things about John Grant over the course of this review, so we should probably pause here and note that no matter how much he loathes his situation – and we will soon learn exactly how much that is – he seems not to have taken his feelings out on his students, with whom he clearly has an amicable relationship. Nearly all of them have a friendly work for him at parting; one shakes his hand, another offers the gift of a specimen for his rock collection; though it may be with malice aforethought that one of the older boys offers the parting shot, “See you next year, mate!”

We then follow Grant across the railway tracks to his room at the pub, where he packs his bags. The handful of sketches that decorate the walls suggest that (like his creator) Grant may have arrived in Tiboonda with misplaced, and short-lived, romantic notions about “the outback”. However, whatever idea there may initially have been about filling spare time with “art”, after sketching the schoolhouse, the pub, the skeleton of a cow, a passing horseman and a dead tree, Grant evidently felt that he had exhausted the artistic possibilities of his surroundings.

(In fact, these productions speak more to Grant’s meagre talents than to a lack of material. There is a macabre beauty in the surrounding landscape, but it would take the eye and the sensibilities of a real landscape artist to do it justice.)

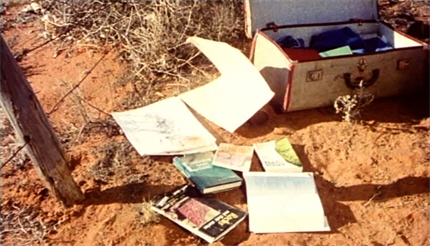

Grant also gives himself away with his choice of books, which seem chosen more to prop up his conception of himself than to while away the hours. We note Plato’s Republic amongst them; Grant will later quote the Rubaiyat to an unimpressed listener.

Downstairs, Grant has a smoke and a beer – the first of very many to follow – and responds to the unspoken expectation of the publican Charlie by inviting him to have a beer also. Even so, his slowness in paying provokes the wry inquiry, “Got snakes in your pocket?” An odd exchange follows about Grant’s room, in which the surface humour of the remarks carries an undertone of genuine hostility—on both parts. We get the impression here that however little John Grant thinks of Tiboonda, Tiboonda – in the person of Charlie, apparently its only permanent resident – thinks even less of him.

The sound of the approaching train cuts short this interchange, however, and Grant bolts eagerly for the door. Climbing into the train’s one carriage, Grant finds as seat as far from a noisy, hard-drinking group as possible; and during the long, hot, jolting ride that follows, tries to lose himself in a – memory? dream? fantasy? – of a Sydney beach and a girl with a surfboard…

This first stage of his journey concludes with a cab-ride into Bundanyabba—or “the Yabba”, as its surprisingly enthusiastic residents call it: surprising to Grant, anyway, who has time and enough during his trip to town to absorb the desolation of the landscape, the gaping wounds in the ground, the slagheaps, and the abounding machinery of the true mining-town. The cabbie, indeed, goes so far as to insist that the Yabba is, “The best place in Australia”, adding by way of explanation that no-one worries who you are or where you came from—“If you’re a good bloke, you’re okay.” Indeed…and much of the running-time of Wake In Fright is devoted to the issue of what, exactly, it takes to be considered a good bloke in the Yabba.

The story of John Grant is very much a case of, For want of a nail—, with one misstep leading inexorably to another, and another… He makes his first when, instead of simply hunkering down in his room and riding out the night in the company of Plato, he decides to venture out for a quiet beer.

But in the Yabba, there is no such thing as “a quiet beer”…

Grant’s quest leads him to an establishment which, we note, is packed to the rafters at 8.20 pm in spite of the sign declaring that it is legally obliged to close at 6.30 pm. (Amusingly, when Grant leaves the front door open, he is abused for it: “Hey! Shut the door, mate—we’re closed!” exclaims an indignant local.) Here we find the reality of life in a mining-town, with “the law”, as it is generally understood, is habitually overridden by the law as enforced by the mining-company which, for all intents and purposes, owns the town, and arranges things to suit itself and its employees.

Grant forces his way through the Friday night crowd, which is overwhelmingly though not exclusively male (more on that point in a moment), and manages to acquire a drink and a small patch of wall to place his back against. Whatever hopes he may have nursed of downing his drink in peace before returning to his room are, however, immediately dashed: as an outsider – “New to the Yabba”, as will be obsessively observed by everyone who meets him over the following hours and days – Grant instantly attracts the attention of local policeman Jock Crawford, who subjects him to a well-intentioned but exasperating cross-questioning, all the while – and merely through the power of a look of mingled puzzlement and disapproval at Grant’s dilatoriness in this respect – forcing down his throat more beer than he has ever dreamed of consuming.

The officious, not overly bright, vaguely menacing Jock Crawford is played by Chips Rafferty in his final screen role. Probably the first actor to really represent “Australia” onscreen, internationally as well as locally, Rafferty was more often than not called upon to personify the positive face of Australian mateship and larrikinism—and probably relished this rare chance to play its underbelly instead.

(Fun fact: Chips Rafferty was born in Broken Hill…)

The exchange between Grant and Crawford is a pivotal moment in Wake In Fright—Grant all sarcasm and condescension, Crawford friendly if not always getting the point of Grant’s remarks, which is probably for the best. The full resentment of his position – which, we sense, Grant has learned not to voice to Charlie the publican – comes pouring out here, as he refers sneeringly to Tiboonda as, “Paradise on Earth” and to himself as, “A bonded slave of the Education Department”. Crawford’s attempt at consolation – “You can always come to the Yabba for your holidays!” – falls just a tad flat…

To explain: Grant is part of the system by which at the time teachers were found for isolated or otherwise unpopular locations. Upon graduation, new teachers were required to pay a $1000 bond before they could get a teaching position, and were then compelled to work it off—wherever they were posted. And while it is by no means evident in the experience and attitude of John Grant, it was a system that worked remarkably well, at least for the students. Many graduates of this system speak glowingly of the education they received, albeit that individual teachers rarely stayed longer than they absolutely had to. While holding their posts, however, they seem to have given it their all—probably because in places like Tiboonda, there was nothing to do but teach.

Three rapid beers in, Grant turns the tables and starts questioning Crawford about police work in the Yabba. Crawford admits there’s not much for him to do—there’s not much crime, partly because there’s nowhere to hide; although after a moment’s reflection, he concedes that for some reason, they do have a few suicides…

Grant: “Well, that’s one way of getting out of town.”

Wake In Fright ultimately captures both faces of an aspect of Australian society that has its roots deep in the country’s founding. Reams of analysis have been devoted to the concept of “mateship” and its supposed role in the formation of the Australian character and psyche; only a subset of those studies have chosen to acknowledge the fact that “mateship”, by its very nature, is a concept that explicitly excludes women.

Conversely, all of the iconic roles via which the very term “Australian” tend to be defined are almost invariably male in nature—the digger, the stockman, the swagman, even the bushranger. The qualities upon which the country was supposedly built – courage and endurance in the face of war, of natural disaster, of economic deprivation – are also tacitly male: a reading which ignores the fact that whatever has been endured by the Australian male has, of necessity, also been endured by the Australian female—and endured, for the most part, in silence; though of course, her absence from the historical record reflects the control of that record rather than a lack of anything to say.

The nature of the country in its early days did in fact do much to divide the sexes, inasmuch as the men hugely outnumbered the women. A relationship with a woman was therefore simply not an option for a large section of the male population. This situation had two lingering consequences. In the first place, it forced men to make their deepest emotional connections with other men, while at the same time engendering a profound horror at the mere idea of a sexual connection between men (or at least, a profound state of denial); with physical contact permissible only during sport, roughhousing or an actual fight.

Secondly, this divide carried over even where relationships between men and women were possible. A man might marry, but his mates came first; while “men’s lives” and “women’s lives” remained rigidly demarcated: a situation which persisted nation-wide until very recently and, in some parts of the country, still does. A real man was one who could do without a woman; who certainly had no need of women as individuals, as people; still less as companions. A woman might cook, and clean, and bear children, and lie still while you worked out your sexual needs on her, and occasionally take a punch if you felt like it, but the idea you might need her was absurd. Hence the traditional Australian definition of a homosexual, one explicitly evoked in the course of Wake In Fright: a man who likes to talk to women.

And as for the women, they were left to make what emotional support networks they could amongst themselves, something easier in some situations than others. In a mining-town like Bundanyabba, where options were so stiflingly few, the emotional isolation could be even more complete than the geographical—and not everyone survived it.

Jock Crawford is right in what he says about the Yabba’s suicide rate, but he does not address the fact that in this respect, such places invert the national trend: whereas the majority of Australian suicides are male, in remote districts like Bundanyabba, a higher proportion of females take their own lives.

Without emphasising the point, Wake In Fright captures much of this situation—which is reflected in the film’s cast, with only one significant female role. The division between the sexes was, indeed, one of the first things that Ted Kotcheff noticed upon spending time in the outback, as well as how very few women there actually were in many remote areas.

Even here, when everyone is having a night out, the lines between the sexes remain drawn. Other than those behind the bar, the mere handful of women present are gathered together in what is no doubt called “the Ladies’ Lounge”, a couple of couches pulled together in one corner of the room.

Some unspecified time – and an unspecified amount of beer – later, Crawford attempts to steer Grant across the road to a second pub. When he realises that Crawford intends still more drinking, Grant begs for mercy in the form of something to eat. This second pub, “closed” like the other, at least has the decency to douse its lights in the main bar. Beyond that we find a kitchen serving rough and ready dinners, and beyond that a room crammed with men: “Biggest two-up game in Australia!” explains Crawford, cheerfully ignoring the outright illegality of the proceedings, the only acknowledgement of which is a cautious torch shone in Grant’s face at the front door. “He’s all right,” testifies Crawford.

As he watches dozens of men with their attention riveted upon the toss of two coins (briefly: two heads or two tails pays), and the gravity with which they approach what he automatically condemns as “a simple-minded game”, Grant cannot help but notice the very large sums of money that are changing hands…

Grant is called back to the kitchen by the arrival of his steak, two rock-hard fried eggs, some overcooked chips and two slabs of bread. “Best dollar’s worth you ever had in your life!” Crawford declares emphatically before wandering off—a remark which prompts the man sharing Grant’s table to comment quietly, “All the little devils are proud of hell.”

Ever since escaping from the schoolhouse, Grant has been progressively giving in to his feelings of disgust and contempt for everything about him: feelings immeasurably exacerbated by his enforced stay in the Yabba. We have seen him sneer at the town itself, at its residents, at their pastimes, even at the brief memorial service that breaks up the evening (the first pub doubling as the local RSL club); but as soon as the man at the table opens his mouth, everything changes. The observation itself, and the way in which it is made, immediately convinces Grant that he is in the company of an educated man – a civilised man – a man like himself.

And so he falls head-first into a trap set and baited by his own prejudices…

Doc Tydon is indeed an educated man and a civilised man—or at least, he was once. And he really is a doctor. He is also an alcoholic, which in most places would be a hindrance to the practice of his profession, but which in the Yabba, where men are eyed askance if they decline any opportunity to consume alcohol, is more in the nature of a recommendation. All this Grant will learn in time. For the moment his attention is caught by the fact that here, at last, is someone who doesn’t seem to think that the Yabba is, “The greatest little place on Earth.”

This first exchange between Grant and Tydon is fascinating and profound. I must confess, I find myself more in sympathy with Grant here than I am entirely comfortable with, though I hope I am not operating from the same basis of class prejudice. Be that as it may, his complaint about the aggressive hospitality of the locals, as evidenced by Jock Crawford’s absolute refusal to take ‘no’ for an answer at any point, touches a chord deep within my introvert’s soul, where lurks a horror of forced social gatherings and small-talk with strangers; while for better or worse I find myself nodding in agreement when Grant further condemns, “The arrogance of stupid people who insist that you should be as stupid as they are.”

But— Doc Tydon is absolutely right when he counters Grant’s accusations by observing that if people have to live in a place like the Yabba, they might as well like it:

Doc Tydon: “Discontent is the luxury of the well-to-do… It’s death to farm out here; it’s worse than death in the mines. Do you want them to sing opera as well?”

In fact, Doc is philosophical about the Yabba’s vagaries:

Doc Tydon: “Could be worse.”

John Grant: “How!?”

Doc Tydon: “Supply of beer could run out.”

(Honest to God— I cannot even begin to imagine how the South Australian Brewing Company, whose West End beer floods almost every scene, must have felt about Wake In Fright. It’s not so much product placement as product character assassination.)

While this conversation is going on, the viewer learns various things about Doc Tydon—chiefly, that he lives by barter (he has no income as such at all, Grant finds out later), and by scrounging. Unashamedly, he takes to himself Grant’s discarded eggs and bread, and looks at his companion hopefully when he finishes his beer.

Grant deflects the silent plea, but Doc does get a beer from another source, being given one in exchange for his advice on how the coins are running next door: “It’s a spinner’s night, nearly two-to-one on heads.”

And it may be this that sends Grant back into the two-up room, determined to try and win his way closer to an escape from his bond.

The following scene is absolutely crucial in the overall context of this film, not just because of its consequences for Grant, but because of what it tells us about the locals—and Grant’s attitude to them. Yes: they are loud, and they are crude, and they are drunk; but they mean Grant no harm, and they do him no harm.

In fact, on the contrary: observe how he is treated here. The others notice his uncertainty about how to proceed at the two-up game, but no advantage is taken of him; and if they grin at him, it isn’t unkindly. Grant’s first bet is a winner—but in the rush to collect he is shouldered out of the way and pushed to the back. A sour smile has barely begun to slide across his face – “That’s the last I’ll see of my money,” you can almost hear him thinking – when a voice is calling out for, “A bloke with a coat on”, and his money is being passed back to him over the heads of the crowd: a crowd which then takes pity on the rookie and shoves him into a prime position in the front row.

Grant fails to absorb the implication of this interaction, being wholly intent upon the game and his money—and for good reason. His foray into the two-up room is even more successful than he dared dream, and he runs back to his hotel room clutching banknotes in both hands, so close to release from Tiboonda that he can almost taste it.

He’s not quite there, though – perhaps a few months away – but as he stares down at the cash that represents so near and yet so far, he makes a fatal decision; one that not even the amount of beer he has consumed can excuse—because he stops and thinks about it, and then he does it anyway…

The next morning finds John Grant stranded in the Yabba, his flight to Sydney having evaporated along with, first, his earlier winnings and then his year’s final paycheque; too broke even to afford his four-dollar-a-night hotel room; left with little more than a dollar in his pocket—the deposit on his room-key which, in another display of innate honesty, the receptionist calls him back for when, overwhelmed by his situation, he starts to wander off without it. Inescapably, Grant ends up back in the pub. It’s Saturday morning, and only that and the larger stores are open; the labour exchange, his first port of call, was not. In a cruel cosmic touch, as he steps away from that building’s locked doors, the flight out from the local air-strip passes overhead…

At the bar, Grant attracts the attention of a middle-aged man called Tim Hynes. “Hot,” is Hynes opening gambit. He follows up with something even more original: “New to the Yabba?” Grant is, to put it mildly, not in the mood; he finally snaps at Hynes, professing his dislike of the Yabba but also explaining impatiently that he’s broke and can’t afford to repay his offer. To his surprise, Hynes responds by losing his temper:

Hynes: “What’s that got to do with it, man? I said I’d buy you a drink; you don’t have to buy me one!”

At Hynes’ raised voice, conversation in the pub tapers off and heads start to swivel. But even as the shocked Grant gropes for a reply, Hynes grins in a friendly way, holds out his hand, and introduces himself.

It seems to dawn upon Grant that Hynes, in his casual but neat and clean clothing, hat and bowtie and all, looks a different proposition from the rough working types who make up most of the local population, even if his conversational gambits are identical.

Other than Doc Tydon – and whatever the Doc may have been once, we know what he is now – Hynes is the closest thing to a middle-class person that Grant has so far seen in the Yabba; that is, to a person like himself. This may explain why, some time later, we find a distinctly drunken Grant playing billiards with Hynes and even laughing at his jokes. Having established that Grant has no resources whatsoever – he being neither a Mason, a member of the Buffalo Lodge, nor a Roman Catholic – Hynes invites him home to lunch.

At the end of the drive, Grant finds a pleasant surprise waiting for him: Hynes actually owns a house, a nice house with a garden (sort of) and a picket fence, and interiors which, if rather formally arranged, are immaculately kept.

But as we and Grant alike soon realise, the condition of the house has nothing to do with Hynes, and everything to do with his daughter, Janette: a woman just sliding out of youth, whose entire demeanour suggests an aching weariness of soul.

Janette accepts Grant’s presence as, we feel, she accepts almost everything else that life brings her way: without comment, and almost without emotion. At some point, presumably, lunch is consumed, but we see only the bookending drinking sessions, the first of which leaves both Hynes and Grant in a stupor, the second of which starts when they are woken up by the arrival of two noisy young miners, who come bearing a fresh supply of beer and settle in for the afternoon.

It is clear at this point that in his search for a better class of companion, Grant has made a serious mistake. Hynes’ civilised surface is no more than that; he is soon revealed as just as much of a raucous drunk as anyone else frequenting the pubs in town—and they, at least for the most part, need not be interacted with. The fact that Hynes now pours the beer he forces on Grant into a glass, and knows enough to jokingly call it “an aperitif”, only makes it worse.

Grant tries several times to escape his current dilemma, but no-one is interested in helping him; and besides, where is he going to go? The best compromise he can find is to slip away to the kitchen, leaving Hynes and the miners, Joe and Dick (the latter played by Jack Thompson in his film debut), to construct ring-pull necklaces, carry on a bawling conversation about guns and dogs, howl with laughter at nothing, and drink.

(And, by the way, to give us a crush-the-beer-can moment pre-dating Robert Shaw’s by four years.)

Grant’s withdrawal does not go unnoticed, not in its own right, and not in the wake of Janette’s earlier rejection of Dick’s loutish advances:

Dick: “What’s the matter with him? Rather talk to a woman than drink?”

Hynes: “Schoolteacher.”

Dick: “Oh.”

Janette listens sympathetically to Grant’s tale of discontent; it doesn’t seem to occur to him that there might be anything cruel about airing to her his hopes of fleeing, not just Tiboonda, but Australia itself: of packing up his girlfriend, Robyn, she of the snapshot and his fantasies of the surf, and flying off to England.

Doc Tydon’s arrival sets the seal on the misery of Grant’s day; at least so far. It is the signal for the retreat of both himself and Janette, the latter calling back that they’re going for a walk. They get only so far as a secluded corner of the surrounding grounds, however, before Janette is pulling Grant to the ground and unbuttoning her simple dress; beneath it she is naked. There are a few moments of urgent thrashing, but they end abruptly, with Grant pulling himself off Janette and staggering away to vomit copiously into the bushes.

With the same air of hopeless resignation that generally marks her, Janette buttons her dress again and cleans Grant up – as, we suspect, she had frequently cleaned up her father – before turning her weary steps back to the house. Janette has, ironically, made exactly the same mistake as Grant: expecting better from a “better” class of person.

Once back in the house, Grant gives up the fight and is sucked into the maelstrom…

He wakes on a hard slat bed in unfamiliar surroundings, emerging reluctantly into the light to discover himself Doc Tydon’s guest, and sharing the shack on the edge of town he calls home. He finds his host shirtless and busy in the kitchen—and singing opera—and learns that it is 4.00 pm the following day, that is, Sunday.

To Grant’s horror, Doc forces on him both a drink – “Yabba water’s only for washing” – and an indescribable cooked mess.

When Doc begins to discuss Janette, however, Grant interrupts with what is, under the circumstances, an absurdly coy request for a toilet. Doc directs him to his outhouse, but advises him against it: “There’s no-one to see you,” he comments; except that, as Grant begins to use a derelict car as a urinal, he wanders up to stand almost elbow-to-elbow with him…

Despite Grant’s evident distaste, Doc then returns to the subject of Janette: revealing casually that what he calls “an episode” with her is a common activity in the Yabba, one which he sometimes partakes of himself. But though he admits that her behaviour brings upon her the condemnation of the town, Doc himself defends her right to do as she wishes; to “take a man” if she feels like it. In fact, he goes on to ally himself with Janette: they are alike, he observes, in that they are both rule-breakers, but even more so, in that they understand themselves and why they do what they do. There is a message here for Grant, but in his current condition he is incapable of receiving it.

And the horrors just keep coming, as Grant learns that, any moment, Dick and Joe will be coming to take the two of them out hunting—chiefly because, the night before, a drunken Grant was moved to brag about the silver medal he once won for target-shooting while still at school.

Grant’s own contempt of the Yabba finds its counterpart it the attitude of the young miners towards him. The hunting-trip evolves into a particularly vicious sort of peer pressure situation, an open challenge to Grant’s masculinity—one to which he rises, or sinks. At least he knows how to handle a gun, he consoles himself, even if he’s not used to shooting at live targets. As the four men set out in Joe’s car, slamming and bouncing across the rough terrain, Grant determines to prove that he can be one of the boys, a real “Yabba man”. The adrenaline kicks in, on top of the beer; and something else too; something far darker…

Running twelve straight minutes, the kangaroo-hunt sequence of Wake In Fright is one of the most brutal and upsetting things ever committed to film: hugely controversial at the time of its first release, and only becoming more so as ideas about such things began to change. Whenever Ted Kotcheff was subsequently interviewed about the film – and we are speaking of a period of decades – it was invariably the first thing he was asked about; sometimes the only thing he was asked about. His answer never changed: that the footage used was of a real hunt, and not staged for his cameras or influenced by the crew’s presence; yet the question never stopped coming; and there has never been any shortage of people willing, overtly or covertly, to accuse Kotcheff of lying about the origin of this sequence, to excuse his own part in it.

But there are two things which speak independently in Ted Kotcheff’s defence. The first is that there were representatives of the RSPCA on site to monitor what the film-makers were doing in this respect; and the second, that the BBFC – possibly the only people in the world more neurotic on this subject than I am – passed Wake In Fright uncut in 1971, meaning that the organisation was satisfied it had met their criterion of no animal being harmed for the purposes of the film.

They were being harmed, though; worse than harmed. In order to capture the footage they needed, under the guise of filming a documentary the crew organised to go out on a kangaroo-cull. However, so sickened and distressed were they by what they saw (the film’s British producer, George Willoughby, literally fainted), they ended up faking a power-outage in order to cut the nauseating business short. We can well understand that they may not have dared express open disapproval of the activities of the hunters, who were as drunk as the film’s characters. Ted Kotcheff later recalled being offered what he called “a menu of atrocities” by one of them, who claimed to be able to put a bullet into any part of a kangaroo’s body he chose, and could – and did – describe exactly how much physical damage it would do. Far from any thought of putting the animals down as quickly and painlessly as possible, the cull rapidly descended into reckless savagery.

In the aftermath of this, the RSPCA – already grappling with the Sisyphean task of trying to get regulation imposed upon an activity that was simultaneously extremely profitable and conveniently conducted out of most people’s sight – urged Ted Kotcheff to include the very worst of the captured footage in his film, in order to publicise what was going on.

However, though sympathetic to their cause, Kotcheff kept his eye upon what was best for his production. The final edited sequence, horrifying as it is, includes only the least offensive footage – contemplate that on the Tree of Woe – supplemented with some images of kangaroos bounding away normally that are edited to make it seem as if they are reacting to being shot. A tame ’roo accustomed to being handled (“Nelson the Boxing Kangaroo”) was employed at some points, while all direct violent interaction between man and animal was faked—including what John Grant is finally goaded into doing: an action that so wins the approval of Dick and Joe, they gift him the rifle he’s been using.

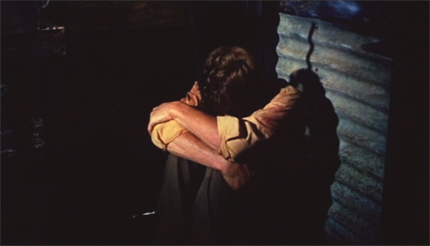

The evening ends at yet another bar. Grant soon passes out, while the other three trash the place in a drunken rampage. However, a misdirected swing of an arm during a faux-fight between the miners triggers a lightning switch from “fun” to the real thing, a grimly serious encounter which ends with the young young men rolling around on the ground together: a tussle in which Doc joins, after being forcibly ejected by the bar’s outraged owner.

Dick and Joe eventually dump Doc and Grant back at the former’s shack. This time it is Grant who goes for the beer-fridge (which is to say, Doc keeps nothing in his fridge but beer); and so in the spirit of things is he, a drunken push-and-shove develops between the two that leads to Grant “christening” Doc with a beer, as he in turn starts discharging the rifle, shooting out one of his own light-bulbs; the two of them laughing uncontrollably the while.

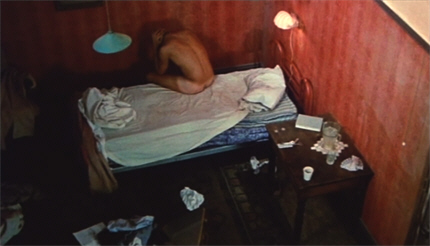

Doc grabs the remaining hanging light and shines it directly into Grant’s face, blinding him. And then Doc pounces—seizing Grant from behind via an arm across his throat and forcing him down onto his mattress…

(This attack mimics what was just done to the kangaroos, which are caught in a spotlight before being blown away with a gun or grabbed from behind for more hands-on dispatching.)

Even now, this a startling moment; but in the social climate of 1971, it must have caused a cataclysmic shock. A scene implying man-on-man rape would have been confronting enough; but what we are actually left with is a clear suggestion that whatever happens after the fade-to-white, Grant is a willing participant.

I commented up above about the contradictory aspects of “mateship”; and we should note how this encounter is prepared for by the behaviour of Dick and Joe, who indulge in some escalating roughhousing that includes clutching, tackling, wrestling and karate-chops, all of which feels more and more like transference, and whose eventual, serious fight ends in an extended clinch indistinguishable from an embrace.

Doc Tydon, however, is not given to disguise; nor to denying his appetites; and what follows with Grant might well have been rape, had it needed to be. Apparently it didn’t…

(There is plenty of anecdotal evidence that for a great many male viewers during the first release of Wake In Fright, this scene was more upsetting than the kangaroo-hunt. The casual male nudity wasn’t popular either: we see a great deal more of Gary Bond than we do of Sylvia Kay.)

The two men wake up side-by-side the next day; Doc clad only in a dirty singlet that covers him just far enough, Grant in nothing at all, as far as we can tell. Grant’s only thought is to get the hell out—out of the shack, out of the Yabba, out of the outback. Out.

“Bye,” says Doc casually.

It is impossible not to laugh at that send-off, which highlights one of the strangest things about this very strange film: it is at times extremely funny. The central block, from Grant’s arrival at the Hynes house to his moment of horrified realisation, the morning after the night before, is pure nightmare; but the sections either side of it are studded with flashes of painful humour.

In particular, the final twenty minutes of Wake In Fright, which find John Grant doing everything he can to escape yet only getting more and more deeply mired in a previously undiscovered Tenth Circle of Hell, play like a grotesque black comedy…although that said, I honestly can’t judge whether a non-Australian would find it funny at all.

So. Grant first walks back to the Yabba, where his appearance – dirty, dishevelled, splashed with blood and carrying a rifle – attracts only glances of mild curiosity from the locals. Almost immediately, he falls into the waiting arms of Jock Crawford. Grant is reduced to begging for a beer and a cigarette, his abject attitude a far cry from his unveiled contempt of three days before. Grant left his suitcases at the pub before he went off with Hynes, and while they are perfectly safe – no dishonesty in the Yabba – the barmaid is suspicious because he can’t remember exactly when that was. Crawford, on the other hand, is prepared to take Grant’s word they’re his—until he makes the absurd claim that one of them is mostly full of books…

That second suitcase is the first thing to be discarded, though, when Grant sets out on foot—seriously determined to walk to Sydney, if that’s what it takes. Plato, Omar Khayyam and the rest end up scattered along the roadside. Grant succeeds in hitching a lift from a truckie that gets him at least a bit further along, but when he resumes his walk it is in the crippling heat of the day. Grant’s first night on the road is spent alone in the desolation; he dines upon a self-shot rabbit that he barely bothers to clean, as he huddles next to a small fire.

The next day he gets a ride from a man driving a jeep, who takes him as far as Silverton…the Silverton Hotel, that is. (A real place, but west of Broken Hill rather than east.) Grant’s only thought is get on the move again, but of course his driver wants him to stop and have a drink—and doesn’t take it well when Grant refuses. Their escalating verbal makes me laugh like a loon, chiefly because the point of view of both combatants is so damn reasonable; also, because it captures something deeply, perversely Australian:

Driver: “What’s wrong with you, ya bastard? Why’d’nt ya come and drink with me? I just brought ya fifty miles of heat and dust, and you won’t drink with me!?”

Grant: “What’s the matter with you people, huh? Sponge on you…burn your house down…murder your wife…rape your child: that’s all right; but don’t have a drink with you – don’t have a flaming bloody drink with you – that’s a criminal offence, that’s the end of the bloody world!”

Driver: “Ya mad, ya bastard!”

(Note that Grant leads with “sponge on you”: earlier, he flinches when Doc accuses him – rightly – of sponging on Tim Hynes; and he certainly sponges on Jock Crawford. He’s ashamed of himself, but he does it.)

Grant sets out on foot through what there is of Silverton, and comes across a parked truck that bears on its doors the magical word, “Sydney.” The driver is of course in the pub – the other pub – and Grant tracks him down, begging for a lift to the city. The driver, unmoved by his plight, demands two dollars—which Grant doesn’t have. He finally hands over his one remaining dollar and his rifle, at which the driver allows him to climb into the back of his truck, where he falls asleep…

…waking to discover that he should have been a bit more explicit about which city he meant:

Truckie: “Bundanyabba’s a city, ain’t it?”

And in a typical touch, recognising that he has somehow disappointed Grant’s expectations, the truckie “refunds” his rifle.

It is at this point, understandably, that Grant snaps. The outback has broken him; he is overwhelmed by disjointed, nightmarish images of his experiences, “hosted”, as it were, and dominated, by a laughing, jeering Doc Tydon, who also appears in persona propria: coupling with Janette, as Grant didn’t manage to do; even coupling with Robyn.

Grant stumbles along the road, heading back to Doc’s shack. Along the way he discards his one remaining suitcase. He keeps hold of his rifle, though, loading it with his last bullet, and bursts in through the door, the weapon cocked and ready. By now he’s convinced it’s Doc’s fault, all Doc’s fault, whatever he might have done. And in one sense, of course, he’s right…

But Doc isn’t there. So Grant sits down to wait, the rifle pointing at the open doorway.

And wait. And wait…

Finally, Grant is left with nothing but his despair. Then he remembers his own words to Jock Crawford, about the one sure way of getting out of the Yabba…

Wake In Fright premiered in Australia on the 9th October 1971—and to describe the immediate reaction to the film as “appalled” would be to greatly understate the matter.

However – and it very important that we are clear about this – it was not ultimately “the Australian public” that rejected the film, but the government and its myrmidons, who were horrified by this first manifestation of the new Australian film industry, and the local critics, whose dreams of respectable productions that would win Australia a respectable overseas reputation, were shattered—and who could hardly wait to say so publicly. Although perhaps no-one was more dismayed than the people connected with the local tourism industry.

And yes, in the first instance the film played to exactly the wrong people, the opening-night crowd and the event-attenders, who reacted with hostility, anger and disgust. That’s not us, they insisted, blaming the “foreigners” who had created this travesty. Except that it was. It was an Australian story based – and closely – on an Australian novel written by an Australian about his experiences in his own country; and that, in the end, was the film’s unforgiveable sin.

But there were also some people, just a few at first, who took it all squarely on the chin. Then word of mouth began to spread – there was little to no direct promotion – and slowly Wake In Fright started to find its proper audience. But before that audience could achieve critical mass, the film was yanked from cinemas (we should also place its distributors, United Artists, on the list of the appalled), and effectively buried. And because it was not allowed to complete its run, it was inevitably a financial failure: a bottom line that gave the newly established government funding bodies an excuse to pull back and re-think this business of local film production.

No-one who saw Wake In Fright during that first brief run ever forgot it, however; and as time passed, it became very clear that amongst those who did were the handful of people who would soon be putting Australia on the world map for its film-making.

With hindsight, the impact of Wake In Fright upon the rising generation of Australian directors is unmistakable, both cinematically and in respect of the film’s wilful disregard of people’s sensibilities in its pursuit of the truth. And perhaps none of those individuals was more influenced than Peter Weir, whose first film, Homesdale, dealt with some of the same themes as Wake In Fright, and who was the first of the new crop of film-makers to figure out how to walk the fine line between commercial success and personal integrity.

Meanwhile—under the title “Outback”, the film was faring better almost everywhere else. Wake In Fright’s world premiere had happened some five months earlier, when (bizarrely enough) it was Australia’s entry at the 1971 Cannes Film Festival. There, the response was entirely different. With no axe to grind, viewers and critics were able simply to respond to its power and daring. Reviews were almost entirely positive, and the film subsequently ran for five months in Paris.

(Thirty-eight years later, under the aegis of Martin Scorsese – one of those who saw it in 1971 and never got over it – Wake In Fright screened again at Cannes, becoming one of only two films ever to play the festival twice.)

The film also achieved a lengthy cinema-run in Britain (whether for its cinematic qualities, or for confirming all the local ideas about “colonials”, I hesitate to guess), played across Europe and Asia, and had a limited release in the US.

That brief American run would turn out to have monumental consequences. This was the early 70s, after all, and when Wake In Fright disappeared from cinemas, it disappeared altogether.

When, many years later, there were the first rumblings of a re-think about the film, it turned out that no-one had a copy of the negative; no-one had bothered to keep one, at least not locally. One was eventually found in Dublin, but this was too damaged to be any use. For a time, it seemed that Wake In Fright was doomed to be a lost film.

Fortunately, one of those freakish cinematic miracles then occurred. The film’s editor, Anthony Buckley, for whom finding a good quality copy became a thirteen-year personal quest, discovered one of the original negatives in Pittsburgh, of all places—in a storage facility, in a container literally marked “for destruction”, and one week off being so.

Restoration, re-release and reassessment followed—and though Wake In Fright has lost none of its power to disturb (and if anything, the hunting sequence is even more controversial these days), it is now not merely appreciated, but widely considered one of the greatest Australian films.

Wake In Fright is a unique piece of cinema, one that manages to portray a particular time and place, and yet to capture something timeless, too. Visually, it is stunning—and intimidating. Plenty of films since have used “the outback” as their setting, but none of them are so profoundly of and about the outback, nor managed to do better in conveying its disturbing sense of suffocating vastness.

With the exception of the sky itself and flashes of the Sydney surf, Ted Kotcheff and his art director, Dennis Gentle, stripped out of their palette all colours other than earth-tones: Tiboonda and the Yabba seem almost like eruptions of the land around them, rather than human attempts to impose upon the environment. The blinding light and the unrelieved harshness of the reds and yellows and browns become ever more oppressive. Also striking is the complete absence of all the usual visual signifiers of outback Australia…except the kangaroos, of course. (No wonder the Tourist Commission hated it.)

Self-evidently, Wake In Fright is not a film to be easily enjoyed; but there is so much in it to admire. The supporting cast – which includes, in addition to those discussed, John Meillon, Norman Erskine, Slim de Grey, Peter Whittle and Maggie Dence – is pitch-perfect, while there is a real courage, I think, given the era of the film’s production, about the two central performances.

Gary Bond was always on a hiding to nothing as John Grant, whose psychological dismantling forms the central thread of the plot; but he gives the film exactly what it needed, with Grant’s initial self-satisfaction and condescending rudeness giving way to embarrassment, anger, violence and despair, as his confrontation with the Yabba strips his soul naked. And not just his soul.

But it is Donald Pleasence who is the film’s bedrock. Pleasence was the kind of actor who could undertake a variety of roles without altering his appearance, vanishing into his characters rather than shaping them to accommodate himself. His Doc Tydon is one of his most unforgettable creations: a master manipulator, intelligent, nuanced and wickedly funny; clear-sighted and unapologetic in his self-indulgence; frequently disgusting, and yet—oddly appealing.

We respond to him, in fact, very much as John Grant does.

The interplay between Doc and Grant is immensely satisfying on a number of levels. It is important, in the first place, that Doc is – unlike nearly all of the Yabba’s other male inhabitants – physically non-threatening. It is precisely because he is so unintimidating that Grant lets his guard down in the first place: the instinctive recoil that occurs in his every other encounter in the Yabba is nowhere to be seen as he responds to Doc’s conversational overtures. That he has, so he supposes, found a kindred spirit in Doc – an educated man, a man from the city – one who shares his opinion of the Yabba – makes him open up. He has no way of knowing that he is sowing the seeds of his own destruction…

There is an unmistakable sense throughout their strange—well, you can’t really call it a friendship—that Doc Tydon is deliberately tearing Grant down to his own level—and thoroughly enjoying the process. And it is precisely because they are men of similar background that Doc knows exactly how to work on Grant. It took five years for the Yabba to turn Doc Tydon into what he is when we meet him; John Grant – with Doc’s help – will reach the same point in three days.

Yet it seems to me that there’s more to it than that. Up to the kangaroo-hunt, much of what Doc says to Grant can be interpreted as a warning – or as offering him a chance to escape – but Grant isn’t listening. In fact, he never listens, unless Doc is saying something that he wants to hear. Certainly Doc’s rumination upon the necessity of understanding oneself in order to survive in the outback falls on deaf ears. If there is then a mental shrug on Doc’s part, well, who can blame him?

And behind all this, there is also a distinct metaphysical aspect to the character of Doc Tydon, whose various appearances – at the pub, at the two-up game, at the Hynes drinking-session, on the hunt, at his shack – each signify a turning in John Grant’s road to hell.

Wake In Fright is that rarest of things, a genuinely unclassifiable film. Cult movie is the soft option: it is simultaneously a horror movie, a psychological thriller, a character study, a black comedy, and an examination of the lives of the disenfranchised. It is both an art film and an exploitation movie. It deals with large and important themes, but with a telling eye for detail. And it handles its subject matter in a way that makes it almost impossible for even local viewers to put their finger on where reality gives way to exaggeration and satire; if indeed it ever does…

It is not correct, however, to say (as many have) that this is “a film about Australia”. Like “cult movie”, that’s too easy a cop-out. Wake In Fright deals with a part of Australia, if you like; one aspect of the country’s psyche; but any summation that tries to simplify what’s going on here is going to lose something vital.

Which brings me to another remarkable thing about Wake In Fright: how non-judgemental it is. This is the main point at which it differs from the book: it eschews Kenneth Cook’s cathartic outpouring of negativity and his reflections upon “good” and “evil” in favour of a neutral tone and a detached attitude.

This was an entirely conscious choice on the part of Ted Kotcheff, who wanted to convey his own torn reaction to his time in Broken Hill. On one hand, he felt a dismayed sympathy for the town’s women, and was horrified by the behaviour of some of the men; yet at the same time he became fascinated – and moved – by what he later called the “fortitude” of the locals: the pragmatic courage displayed in the face of incredible, day-to-day hardship, and the camaraderie on which it was built. The ugliness may have been more readily apparent, but it was not all that was there.

There is consequently a striking even-handedness in Wake In Fright. What happens in the Yabba happens, but the film never treats it like a freak-show, rather as the inevitable consequence of a life dominated by isolation, by hard, thankless, dangerous work, and by heat, and dirt, and flies – and boredom – all of which are an almost palpable presence in the film, and explain, if not excuse, so much.

The cameras record all this; but they record something else, too: the overbearing but genuine friendliness of the Yabba residents, and the peculiarly honest and egalitarian way most of them go about their lives: sharing what they have with those that don’t, on the assumption that they’ll be repaid some time or other; doing their best – as Doc Tydon puts it – to like what they have to like.

We may not care for the specific manifestations of the Yabba’s friendliness – most of us, I suspect, would react just as John Grant does; I know that I would – but we must not fail to recognise these gestures for what they are. If the fragility of civilisation is the overt theme of Wake In Fright, it is only right that we mark the efforts of the locals, in the teeth of overwhelming discouragement, to hold together their own idea of what constitutes civilisation.

Want a second opinion of Wake In Fright? Visit 1000 Misspent Hours – And Counting.

♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦

This review is for Part 4 of the B-Masters’ 20th anniversary celebration!

Very interesting review! I had to read Wake in Fright for school, fourth or fifth form I think it was, and we watched the film as well; this was in the late 70s. I remember a few shots – Grant with Janette, being raped by Doc (there was no suggestion at our school it was anything but rape) and that image of Doc with the coins landing on his eyes. However great a film it is, it’s not one I’d watch from choice, tbh. My sympathies would still be with Grant, or even more, just recoiling from the thought of living in such a place, especially for women. And I live in a country part of Australia …

LikeLike

Thank you! I’m not quite up for it at the moment, but I’m feeling now I ought to re-examine the book for those moments when the film takes its own path; I can’t remember, for instance, how the “rape” scene plays. (I can imagine there used to be a reluctance to see it as other than rape.)

I think it does an excellent job making us empathise with Grant’s situation yet making us see that he’s being an arse. 🙂

Where are you living, if you don’t mind my asking? (You don’t need to answer!)

LikeLike

The wilds of Queensland! Well, semi-wilds. Not in a desert, mercifully. Mind you at least they wouldn’t have bushfires …

LikeLike

I hope you’re keeping safe! 😮

LikeLike

So far, thank goodness!

LikeLike

Maybe the women weren’t silent, but nobody was listening… there’s certainly something to be dug out of there.

I don’t think I’ll be seeking this one out, but it’s fascinating to read about. Thanks!

LikeLike

Oh, I’m very sure they weren’t. It’s just that no-one considered their experiences important or interesting.

(Easy to be silent when there’s literally no-one to talk to.)

Yes, don’t worry: I’m not going to shun anyone over this one! From my own perspective it is imperative but it’s not a film I’d ever force on anyone else.

LikeLike

I can see how this movie would not encourage the average tourist to come visit.

I have several relatives, however, who would probably be first on the plane.

LikeLike

Yes…it’s the people who aren’t put off you have to worry about.

The tourist aspect was probably more of an issue in the time of the whole “kangaroos down the main drag” era. Hopefully the world is past that now. Hopefully…

LikeLiked by 2 people

I actually had some young ninny (American, iirc) ask me if we have kangaroos in the streets when I visited London in the 80s. I’d already told him I lived in Melbourne!

LikeLike

I went from Phoenix to Indianapolis for work in the 90’s, and I was constantly being asked if I had to shake my shoes out in the morning to avoid scorpions. In my 30+ years of living in Phoenix, I have only seen scorpions in the zoos.

One guy from work did get stung (bitten?) by a scorpion, in his garage. The size of the scorpion grew throughout the day, until by the end of the day, it was HALF in the garage.

So outdated misconceptions are common.

I did have lizards all through my mobile home, though.

LikeLike

This is a fascinating review, and what you describe seems to hold the first film I’ve heard of, other than The Proposition, that I as an American would see that doesn’t use the Outback as a metaphor, at least not a romantic one. Films like Picnic at Hanging Rock, for instance, use the ancientness of the continent as a reflection of the terror “civilization” felt in the face of indifferent deep time.

From what I read here, the Outback is probably shown as more itself, without apology or even conscious notice, than any other geographical location on earth. The blankness that seems to lure to soul to wander, only for the soul to realize that whatever it was listening to, it was merely an echo in the huge and utterly mindless void that is this area–the so called “civilized” mind simply cannot hold itself in the face of such sweeping uninterest in its existence.

Obviously the film isn’t just about this but like I said, the use of the actual country sounds unique in cinema.

LikeLike

That’s an excellent observation, and you’re quite right. In most films after this, Picnic as you note but also things like The Last Wave and Long Weekend (very much so), there is a sense of the environment as an actively hostile force. Here they don’t do that and didn’t need to. And it isn’t even a matter of imposing “indifference” or “passivity” or any other anthropomorphic concept upon the outback, it just is, and that’s overwhelming enough.

LikeLiked by 1 person

So happy that you wrote this piece.

I first saw WIF in a bootleg of the “Outback” version in the early early 90s (well before its resurgence {no idea how this store HAD this copy, same thing with another pseudo-lost 70s film I Never Promised You a Rose Garden}) and was completely bowled over by it (Id love you to do Razorback one day too, since both killer animal film and BLATANTLY Australian [Dark Age as well for that matter.])

I consider WIF one of my favorite films of all time now, in my top 25 or so.

Like you I find it to be as powerful and horrific as intended, yet also EXTREMELY funny. It is a witty, thoughtful “horror” film in which no moment is wasted. I consider it a wonderful pre-cursor/companion piece to The Texas Chainsaw Massacre both stylistically and spiritually.

Wasn’t sure how an animal lover such as yourself and a native Australian would review such a film, especially today, but everything you said is about as perfect as one can say.

(Side Note and unrelated… Would love for you to review David Cronenberg’s Dead Ringers as well. Ive never gotten to watch it with a heterosexual woman before, so your thoughts from that angle, plus the biology side of things would be fascinating.)

LikeLike

Thank you for all that. 🙂

I can only agree with you. I’m also very relieved to discover someone else does find it funny; you do start to worry about yourself…

(I’ve been going around saying, “Ya mad, ya bastard!” for the past week; I know it’s only a matter of time before I forget myself and say it to the wrong person…)

Yes, yes, I’m surely going to get around to all that…eventually. Coincidentally I snagged a copy of Dark Age just the other night from our indigenous cable network, where they were running it in a double-bill with The Chant Of Jimmie Blacksmith.

“Dead Ringers: A Film To Watch With Your Legs Crossed.”

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks for this. I’d never heard this film (nor the novel) before and I’m strangely fascinated by this review. I’ve just ordered the novel from Amazon and the movie from Netflix. I don’t know, I just have a thing for unclassifiable and somewhat twisted stuff that can seem humorous but in a kind of disturbing way..

LikeLike

unclassifiable and somewhat twisted stuff that can seem humorous but in a kind of disturbing way

My 18-page review in 16 words. 😀

Okay, but…all care taken, no responsibility accepted. (And seriously, I cannot warn you strongly enough about the hunting sequence.)

LikeLike

Oh, I’m sure I’ll be fast forwarding through that scene. I think I get the point of why it is there and that’s enough for me, and since they claim that it wasn’t made for the “purposes of the film” I see no real need for me to sit through it.

LikeLike

Ok, that was pretty grim, but that doesn’t mean that I didn’t immediately watch it again with the audio commentary! Simply fascinating.

LikeLike

Well done you! I’m relieved you didn’t emerge from it with a lasting grudge. 🙂

LikeLike

Hmm… starring Gary Bond, Donald Pleasence, Chips Rafferty, Sylvia Kay….. DONALD PLEASENCE! Oh, I AM watching this movie!…Uh… the kangaroo hunt… aw, rats. I don’t think I can do it. Unless… anyone got time stamps for when I have to look away from the screen and when it will be safe to come out of hiding again?

I was also interested in what is shown about outback Australia here. My dad’s family lived in a remote mining town in northern Manitoba (1939 into the 60’s) and a couple I know met in the same town in the 80’s (she was born there and he met her when he was flying Cessna 185’s and Beavers in the area). Despite the similarities of remoteness, a potentially harsh environment and the realities of a place where pretty much the entire economy hangs on the whims of a single mining company it seems their lives were in many ways very different from what is described here. Heavy drinking seems to be something both have in common though!

LikeLike

I don’t have time stamps but if you pause the first instant you see a kangaroo and then skip forward 12 (or to be safe, 13) minutes, that should do it.

(I’ve put the film away but I can dig it out and work it out if you’d prefer?)

Yes, it sounds like that was Ted Kotcheff’s experience: he was prepared for the similarities but not for the magnitude of the differences.

LikeLike

Thank you! That should be enough to let me avoid the psychologically damaging bits:-) I really do have to see this because I always love seeing Donald Pleasence in… well, anything really – and the way you describe the character and his performance make it a must watch.

LikeLiked by 1 person

So now I have to ask – do you know The Barchester Chronicles? Donald Pleasance, Alan Rickman, Nigel Hawthorne, O my!

LikeLike

…and that horrifying moment when you realise you have a crush on MR SLOPE. 😳

I nearly mentioned that. It illustrates what I meant about Donald Pleasence as an actor, able to be completely different people without changing himself.

LikeLike

Ray, in case you haven’t seen it, there is now more accurate time-stamp info in comments further down.

This film is imperative from the Pleasence point of view. 🙂

LikeLike

I love Mr Slope! He’s so wonderfully slimy. And Mrs Proudie, and Dr Grantly, and Bertie Stanhope.

I remember when the casting for the first Harry Potter film was being announced in the papers. I asked my mum “Who would you pick to play Snape?” and it took her about one and a half seconds to say “Alan Rickman.”

LikeLike

If you’re watching it on a DVD the relevant chapters to avoid are chapters 8 – The Kangaroo Hunt and 9 – She’s a Beauty. The real and horrible night scenes are all in chapter 9. Chapter 8 is mostly drunk guys in moving truck shooting at, and missing. running kangaroo stock footage. The do hit a kangaroo with their truck in this chapter it’s not real event though and you really don’t see the actual act that clearly. There is a kangaroo corpse as a result of the hit, though I’m not sure if it’s real corpse or not.

LikeLike

Oh:

Chapter 8 – 1:08:20

Chapter 9 – 1:14.41

LikeLike

Oh:

Chapter 8 – 1:08:20

Chapter 9 – 1:14:20

LikeLike

Uh, oh again:

The kangaroo stuff in chapter 9 lasts until the 1:21:48 mark.

Lyz, feel free to consolidate all this into one post.

LikeLike

I think we are seeing some NTSC / PAL time differences here.

Working with a PAL recording – not a DVD with chapter stops – I time the sequence as occupying 1:06:54 – 1:18:33 (from the first glimpse of a kangaroo to them throwing bottles at the pub to wake the owner).

Working with (I assume) an NTSC copy, Eric gives us the sequence as occupying 1:08:20 – 1:21:48.

LikeLike

I was planning to watch the movie this weekend as it’s on The List and I know it’s readily available on the Roku, so I could finally read the review. Then my weekend got flipped upside-down and I had no time. Then it occurred to me that, with your handy new tags, I could see if there was anything I should be wary of, remembering you mentioning it taking you a decade to get to this over at B-Masters.

And thus, seeing the tags, I read the review, which was naturally marvelous. I love the way you can shift your writing so easily to match a movie’s tone. Anyway, I’m glad I did because I still want to see it, but the hunt would’ve been a nasty surprise and I’d much rather be ready for something of that nature.

LikeLike

Thank you, m’dear.

No pressure from my end for this one. Please proceed with caution.

LikeLike

I enjoyed the review, but I never ever plan to watch it, but it does stick in my mind. I had a thought a few days after reading the review – is it possible he’s really dead, and this really is Hell? The part where he thinks he’s going to the city and winds up back there is the part that really gives me the creeps. Just think of committing suicide because you can’t stand it any more, and waking up the next morning.

Of course, as you mention, the fact that this is a real place, and told by someone who really lived there, makes it even scarier.

I live in Arizona, which has deserts too (the same, only different). If I ever come across it, I might watch it with the sound off, just to enjoy the scenery (and fast-fast-forwarding through the hung).

LikeLike

That does sound terrifyingly like a vision of Hell.

LikeLike

It’s hell, all right…but only hell on earth. But yes, the details you mention are absolutely a large part of the horror.

LikeLike

El Santo’s review of “Wake in Fright” got me to add the movie to my Netflix queue. You review gets me to push it to the top. Thank you, Mz Lyz.

LikeLike

Thank you. 🙂

LikeLike

Fascinating review. Not for the first time, I feel like you’ve helped me understand bits of Australia I didn’t understand before.

“a place where agoraphobia and claustrophobia collide: an infinite space in which there is nowhere to go”… Chilling.

LikeLike

Well, there’s a reason why we don’t generally talk about those bits. 😀

LikeLike

So, I saw it last night. Through coincidence or kismet, a local theater had a showing of the 35 mm print. I’m glad I had the opportunity, as obviously the vast, bleak beauty of the Outback can only be enhanced seeing it this way. A lot of it reminds me of parts of South Dakota and Arizona, although they of course aren’t nearly so isolated.

It is a credit to Our Donald that he walks off with every scene he’s in, as everyone else does quite well with who they’re playing. I also really enjoyed Rafferty, and his early scenes with Bond are probably my favorite part for the interplay between them. It was fascinating how a place as friendly and guileless as the Yabba could still feel so sinister, even before the drunken fighting and animal slaughter and all.

As for that…for whatever reason, I resolved to face the hunt head-on. I did make it, albeit with considerable wincing, and a couple of instances where I wish I’d looked away after all. Not sure why, but while I certainly took no joy from it, I feel I’ve seen far worse.

I can see what you mean, Lyzzy, about trying to classify it. It felt more character study than anything, but…yeah. Especially since it goes places I wasn’t expecting, and made me more than once reconsider what I was seeing, what I had seen, and what it all meant.

I’m definitely glad I saw it, but it’s certainly going to be hard to recommend to people.

LikeLike

Very brave of you, m’dear! Or very silly. Take your pick. 🙂