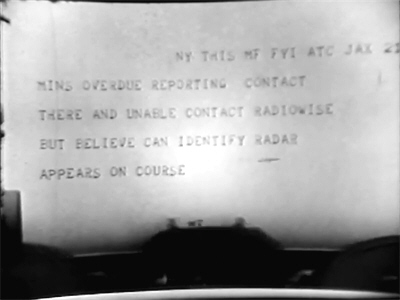

“The plane is flying. They seem to think he’s coming into Idlewild, where he was supposed to all along. They’ve spotted him visually – he’s back on radar – but he’s got no radio, no lights…”

Director: David Swift

Starring: William Lundigan, Betsy Palmer, Keenan Wynn, Shepperd Strudwick, Regis Toomey, Jack Haley, Jane Greer, Charles Bronson, Jay C. Flippen, James Gleason, Reginald Gardiner, Buster Keaton, Ron Hargrave, Chico Marx, Sylvia Sidney, Harry Einstein, Florence Halop, Robert Bailey, Jim Bannon

Screenplay: Charles Einstein and David Swift, based upon the novel by Charles Einstein

Synopsis: In a rising storm, South Coastal Airlines Flight #214 takes off from Miami International Airport, bound non-stop to New York. The plane’s first check-in point is Jacksonville—but the call is not made. In the air-traffic control room, the supervisor (Robert Bailey) puts out a call, but there is no response; nor are his instructions to make an identification turn followed, suggesting that the plane can neither send nor receive transmissions. The supervisor alerts the airports, and the offices of South Coastal in Florida and New York. At Idlewild, the notification is received by Willard Trace (Ron Hargrave), the operations officer, who also happens to be the younger brother of the flight’s pilot, Mike Trace (Jim Bannon). Willard’s first impulse is to contact the airline’s vice-president, Marshall Keats (Keenan Wynn), but he is discouraged from doing so by his older colleague, Ernie Harrison (Buster Keaton), who warns him about sticking his neck out. Willard follows his advice, but makes a different call… As Emmy Verdon (Betsy Palmer) prepares their dinner, Ben Gammon (William Lundigan) takes steps to ensure that they are not interrupted—including cutting off an incoming call by telling Emmy it was a wrong number. The second time he calls, Emmy herself cuts him short—preparatory to an argument with Ben over his behaviour in general, and his jealousy of Mike Trace in particular. The argument has an unexpected outcome when Ben proposes marriage… On Willard’s third call, however, his grim message is received: Emmy is frightened by the news, while Ben – a reporter – immediately takes advantage of this scoop, contacting newsroom, and tracking Marshall Keats to a nightclub. There, an impatient Keats is giving only half an ear to an advertising pitch being made by Felix Allardyce (Reginald Gardiner). The meeting is interrupted when Willard finally gets the nerve to break the news to Keats—who has no sooner heard it than he is appalled to discover the same story being broadcast on the TV news. Ben Gammon catches Keats on his way out of the nightclub, dragging from him a promise of the missing flight’s passenger-list under threat of negative publicity. Soon the story of Flight #214 is all over the newspapers and airwaves. Not everyone is upset: manager Stanley Leeds (Jack Haley) sees in the possible tragedy some welcome publicity for his client, Karen (Jane Greer), a struggling singer—who also happens to be Mike Trace’s ex-wife. Meanwhile, new in-laws, Mr and Mrs Kramer (Chico Marx, Sylvia Sidney) and Mr and Mrs Laurie (Harry Einstein, Florence Halop), try to convince themselves that their honeymooning son and daughter could not be on the missing plane—but the release of the passenger-list confirms their worst fears. Also on the flight are the wife and baby daughter of prize-fighter, Albie Webber, who is at that moment fighting for his championship belt…

Comments: Though there were earlier experiments with the genre, the disaster movie as we now know it is usually dated from 1954’s The High And The Mighty. The most remarkable thing about that film is the way in which what we now consider the tropes – not to say clichés – of the disaster-movie genre hit the ground running—born fully grown, like a motion-picture Minerva, from the imagination of author / screenwriter, Ernest Gann.

The first crop of subsequent disaster movies were therefore almost forced to operate within the very narrow band of wriggle-room left to them by their model—for the most part finding either a different reason for a plane to be in danger, or a different outcome to a case of engine-failure.

The one exception to this rule also found a different way of handling a story about a stricken plane—and in doing so, only four years into the modern disaster cycle, effectively turned all those rapidly established tropes and clichés on their head by giving us a disaster movie in which we do not see the disaster.

Like The High And The Mighty, No Time At All was based upon a novel, a work of the same name by Charles Einstein which was published in 1957. The following year, Einstein was invited to adapt his novel, not for the cinema, but for the small screen.

Co-written with director David Swift, No Time At All was produced as part of the CBS network’s Playhouse 90 live-drama series. Running from 1956 – 1960, and broadcasting each Thursday night, the show separated itself from the pack by allocating a ninety-minute time-slot for its drama productions, rather than the standard sixty minutes: bragging – and not without cause – that this allowed them to handle their material in a more serious manner, and with greater depth.

However, this manifesto put immense pressure on everyone involved. To relieve at least some of it, the series included both live television and filmed productions in its schedule, on a three-to-one basis. The fourth Thursday of every month was the designated time-slot for the filmed dramas, which allowed for sprawling storylines and mixed settings, as opposed to those of the more confined live dramas, as well as more extensive casts.

Running an eye over the films produced as part of Playhouse 90, and the talent involved in them, it is not difficult to appreciate the magnitude of the threat posed to cinema by the medium of television at this time. This program in particular acted as a magnet for directors, writers and actors—in the latter case, often constructing slightly off-kilter casts that mixed screen actors whose star had waned with up-and-comers for whom television was neither good or bad but just a welcome new opportunity.

With the filmed dramas, however, casts featuring older, screen-trained actors tended to predominate. Such is certainly the case with No Time At All, whose familiar faces almost overwhelm the story being told, and in which even the bit parts are filled by a “name”—in some cases, uncomfortably. We may be inclined to feel that the people involved deserved better, though no doubt the actors were happy just to be working (and in such company!).

No Time At All is about a plane that loses all contact with the ground only minutes after take-off, and subsequently disappears from radar. The film opens with footage of the plane taking off, and that is almost the last we see of it. From the earliest moments of the situation, there is a fear that the plane has crashed, or that the pilot has been forced to ditch: “a fear”, because neither the characters nor the viewer knows. The story of the unfolding crisis is told entirely from the perspective of those on the ground: the airline executives and employees, the media, and of course the families and friends of those onboard.

South Coastal Airlines Flight #214 takes off in difficult conditions from Miami International Airport; while the action proper of the film begins in the air-traffic control-room of Jacksonville Airport, where – only nine minutes into its scheduled flight – the plane fails to make contact. The air-traffic controller can still find it on the radar – he thinks – but it does not respond to radio calls, nor does it do an instructed turn, to show that it can receive if not transmit. The controller’s supervisor orders messages sent to both airports involved, and to the offices of South Coastal.

The film then cuts to the operations room at Idlewild, and we have the first of our, “Oh, hey!” moments, with an appearance by Buster Keaton.

(We are here informed that no less than five dogs are being transported by #214: this would-be jokey bit made my hair stand on end.)

It isn’t clear whether Keaton’s Ernie Harrison is in charge, or just older than the rest…and perhaps concerned about his job. Either way, it is Harrison who receives the message about #214—and also he who dissuades his much younger colleague, Willard Trace, from personally alerting the airline’s executives.

For Willard, the silence of the plane has a deeply personal aspect: his brother, Mike, is the pilot. He allows himself to be argued out of calling the airline’s vice-president of operations, Marshall Keats, about the situation; but he insists upon making a different phone-call, to someone he refers to as “Mike’s girl”…

No Time At All is all about its ensemble cast, as a good disaster movie should be, and we are therefore exempt from any obligation to think of William Lundigan’s Ben Gammon as its hero, even though he gets billing—and thank goodness. I’m not entirely sure how we’re expected to take Gammon, but I know how we do take him: he is obnoxious both personally and professionally: whiny and entitled in his relationship with Emmy Verdon (more on her in a moment), and unscrupulous as a reporter. His first action is to intercept a telephone-call for Emmy, not bothering to discover first who was calling or what it was about, and then to childishly hide the phone under a cushion, as if that’s supposed to stop it ringing.

Despite Gammon’s claim of a wrong number, Emmy has a moment’s premonition of something being seriously wrong:

Emmy: “I’m just being silly. I always do that.”

Gammon: “Being female again?”

One minute in, and we’re already wondering what Emmy is sees in this jerk—and not least because she’s played by Betsy Palmer at her most sweetly domestic. (This is the kind of film that helps you to understand why Pamela Voorhees caused such a cataclysmic shock.) A lot of annoying, talking-over-the-top-of-one-another dialogue follows, which boils down to Gammon resenting that Emmy divides her social time between him and Mike Trace, who he insists upon calling her “fly-boy”. Emmy explains reasonably enough that she likes spending time with Mike; but that, while he did propose to her, it happened way too fast; and in fact her instinct is that he’s still in love with his ex-wife.

None of this does anything to stem Gammon’s whining, which itself turns a little too abruptly into a proposal of marriage. However, Willard Trace’s third attempt to get through to Emmy finally hits the mark, interrupting this scene and causing Emmy great distress—though when she confides in Gammon, he sees nothing but an opportunity. Ignoring Emmy’s protest that Willard told her about the plane in confidence, Gammon immediately phones the story through to his newsroom, and is sent off in pursuit of Marshall Keats.

So much for his proposal of marriage. Oh, and at this point we learn that Gammon has a drinking problem, too. Emmy must be counting her blessings.

Now—thanks purely to Da Movies, I’ve always thought of New York’s 21 as a pretty sophisticated place; but No Time At All makes it look like a rather dreary retreat for jaded business types. (I suppose it could have been both?) Anyway—this is where we find Marshall Keats.

Keats is played, much to my amusement, by Keenan Wynn, who at this point in his career just couldn’t stay away from aeroplanes. Even more amusing is that here, in 1958, Wynn has a respectable, under-control moustache—as opposed to the ridiculous walrus-y thing he was carrying around two years later, in The Crowded Sky. So what happened, Keenan? – midlife crisis?

Keats is meeting with two advertising executives, who are trying to pitch him a new, comprehensive promotion campaign for South Coastal. Felix Allardyce preens himself upon his creation of a new company slogan, which he sees as the basis of the whole campaign:

Be There In NO TIME AT ALL.

Keats is already in a state of irritation, one caused by Allardyce’s persiflage and his overweening self-satisfaction with his slogan, when he is called to the phone. The silence of #214 having continued, Willard Trace has finally steeled himself to contact the executive, asking for instructions. Keats’ only instruction is for Willard to keep his mouth shut about the situation—and the words are barely out of his mouth when the TV over the bar in the nightclub is broadcasting the first report of the presumed air disaster.

(This is almost the last we see of Willard, so I’d better say this now: the actor playing him is unbilled, but I think it is Ron Hargrave, who later achieved a very different kind of fame for his ukulele playing, and as a songwriter for Jerry Lee Lewis. Anyone know for sure?)

Keats is on his way out the door when Ben Gammon confronts him, being his usual charming self: threatening Keats with everything up to and including the loss of his job, if he doesn’t hand over a passenger-list for the missing plane. Keats surprises us with his spineless capitulation, promising to make a list available from South Coastal’s Miami office—on condition:

Keats: “I don’t want any tabloid stuff from you. That plane has not crashed yet. That plane is still on the radar screen. He’s still flying.”

Gammon: “Maybe. And maybe we’ve got the story before the plane crashes.”

Yeah, well—good luck with that!

And so it is that those people with friends and relatives on the flight find their situation being splashed all over the newspapers and radio, and regularly broadcast via TV.

No Time At All opens up here, shifting its focus to those on the ground as they wait for news (and with the guest-stars coming thick and fast).

Our first stop is with alleged singer-manager Stanley Leeds, who hasn’t been near his client in months—but seeks her out in a second-rate nightclub once it dawns on him that he can use the assumed death of her ex-husband for some publicity.

(Mind you— I see very little difference between this “dive” and the film’s version of 21.)

Here we see that Emmy Verdon may well be right about Mike Trace still being in love with his ex-wife, because Karen Trace is played by a slinky-evening-gown-clad Jane Greer.

Across town – in the very Jewish section, oy! – we meet up with two middle-aged couples as they learn that their newly married son and daughter are on the missing plane. The reach is a little broad here, with (alleged) humour giving way to tragedy, as the passenger-list is read out on the TV news; but the viewer will probably be distracted by the bizarre co-casting of Chico Marx and Sylvia Sidney as the parents of the bride. Sylvia, as we know, kept on working even before she went on to a late-career second-blossoming thanks to Tim Burton; but while the networks were still fighting over Groucho’s services at this point, Chico’s career was basically over; and this brief screen appearance was his second-last.

Then No Time At All takes perhaps its most bizarrely amusing turn – entirely accidentally – as we cross to the championship fight between Albie Webber and Wolf Hagen.

The actor playing Webber is also unbilled, and I’m not sure who he is*; but Hagen is played by Charles Bronson; while his manager is played by Jay C. Flippen, and his trainer by James Gleason.

See what I mean about this film?

(*I am now informed that Webber is played by Richard Crane.)

And while the sight of an overly sensitive Charles Bronson can’t help but be a bit funny these days, the situation here is genuinely unnerving: Webber’s wife and baby daughter are on the plane; and while it isn’t clear whether Webber himself knows it, Hagen does—and he can’t bring himself to really hit his opponent, much to the disgust of his unfeeling entourage:

Manager: “How do you know it’s the wife and kid of Albie Webber the fighter?”

Hagen: “How many Albie Webbers are there?”

Wolf ends up choosing to take a dive, while the disgusted crowd boos and hoots.

Once in the dressing-room things only get worse, as Wolf’s manager goes to town on him for throwing away such an opportunity for glory for both of them; admitting that while in his career he may have crossed the line once or twice – just once or twice – he never, never, never—

Trainer: “That time in Omaha you did.”

Having delivered in detail his vision of Hagen’s grim future, his manager quits—going out the door as Webber comes in to find out why Hagen took a dive, as he knows he did. Hagen had assumed all along that Webber must be aware of his situation, and now says just enough to alarm him. Webber is quickly taken away by his own manager who, it turns out, did know before the fight, but kept it from him.

We cut back to air-traffic control along the east coast: Charleston reports that they had a blip on their radar which they thought was #214, but which has since disappeared. No-one else has anything—and consensus is that the plane has ditched. Air-sea rescue units are sent out into the night to search for survivors…or anyway, the wreckage.

Gammon, meanwhile, has returned to Emmy’s apartment; and we get one of those infuriating scenes when a woman with every right to lose her temper ends up apologising for going so: “Don’t take it out on me,” Gammon protests, at the end of an argument that started over his violation of her confidence. He also tries to calm Emmy by telling her that’s she’s jumping to conclusions and getting upset over nothing…which is not what he said to Marshall Keats…

The argument is interrupted by yet another phone-call from Willard, from which Emmy draws a grim conclusion…

(We can only assume that Willard is no fan of Karen Trace. The way he forces the crisis upon Emmy, his determination to cast her as “Mike’s girl”, is very strange.)

At Idlewild, Keats comes slamming into the operations office hunting for Willard’s blood; although as he did not, strictly, call the media, Willard denies all charges.

Keats’ rant is interrupted by the arrival of Philip Reagan, the head of air-traffic control for New York, whose quiet, level-headed demeanour is in stark contrast to Keats’ bluster and blame-gaming. The question of a dangerous cargo is swiftly disposed of – “Fish! Two thousand pounds of frozen Florida fish!” – while Reagan tells Keats that Norfolk Naval Base last had his plane on their radar, but contact was lost. The most likely explanation is that the plane has ditched – or crashed – but Reagan invites Keats to the tower, where they may have an update. He goes, but not without one more blast directed at his employees.

No Time At All continues (as it were) to drift up the east coast, with Cape Charles (in Virginia) being name-checked. The situation offers one late-middle-aged man a chance for glory: as his unsympathetic wife scolds (if he catches cold, she will have no nurse him), he searches out his civil-defence helmet, arguing that he has a great responsibility:

Husband: “You heard the radio: there’s a plane lost.”

Wife: “So Errol Flynn is going out into the night to find it? Couldn’t even find your socks this morning…”

Husband: “The ground-observing corps is a tight-fisted group of dedicated volunteers—”

Wife: “Here comes the speech.”

Husband: “They have made me an airplane spotter!…and you know something, Mother, in two years, I haven’t spotted one single, solitary aeroplane…”

What’s interesting here is the facetious tone. The ground-observing corps was a Cold War civil-defence operation tasked with giving early warning of any potential sneak attacks by the Russkies, and this rather jokey invocation of it comes only three years after a deadly serious recruiting-drive resulted in some three-quarters of a million people signing up to “keep watching the skies”. The tacit suggestion here that they were wasting their time is rather daring.

(The organisation was treated much more respectfully in the previous year’s The Deadly Mantis.)

Having revealed that this retired couple moved to the Virginia coastline – onto one of the barrier islands, we gather – just so the husband could be a spotter (!), No Time At All takes pity on him: he gets his wish of spotting “just one plane”…

We then cut to the tower at Idlewild, which is under the supervision of Joe Donaldson. Reagan and Keats arrive just as the message is relayed from Virginia: the plane is still in the air, though flying at only 500 feet; and flying completely dark: “a ghost ship”.

Keats’ relief is tempered by Donaldson’s rather quelching suggestion that they don’t know this is the right plane, or for that matter if the spotter really saw something, or is just some nobody wanting to involve himself in the situation. (He is…but he did…) However, confirmation of a sort comes in the form of a follow-up report from Elizabeth City, NC, which claims to have the plane back on radar. The uncertainty sets Keats off again – “I don’t think those men of yours know their business!” – but a flurry of incoming reports about an unidentified four-engine plane heading northeast confirms that #214 is still in the air.

Reagan suggests that, shortly after take-off, the plane lost its electrical system; and that between its fuel load, the weight it was carrying, the rising storm and the falling “ceiling”, the pilot decided that turning back to Miami was not an option.

Keats: “Then it’s flying – just like I said it would! Despite all those scary headlines! They want a headline or two, I’ll give ’em a headline…”

As Keats grabs a phone and starts bellowing into it, Reagan and Donaldson confer. They agree that the plane’s disappearance from radar was due to how low it was flying – coming in low to try and get a visual “fix” – low enough to be spotted from the ground, in the dark. They debate where it might be headed: something only the pilot knows, and which he can’t tell them…

…which doesn’t stop Keats shouting down the line (presumably at Ben Gammon’s newsroom), “Idlewild! – and you can quote me!”

The other two are briefly dismayed by this, but then realise that Keats is probably right, albeit accidentally: the storm means that there are only a few places the plane could land, and Idlewild is one of them. They begin making preparations for a crash landing…

Meanwhile, a remorseful Karen Trace is pouring out her regrets to a disinterested Stanley Leeds. Her first impulse is to blame Mike’s job for the breakdown of their marriage, though she soon admits her own culpability: that she didn’t want to be “trapped” like all those other wives; worse still, that she had no talent as “a homemaker”.

(Again…this is Jane Greer: anyone expecting a conventional housewife…)

Leeds says the right things, if not in the right tone, but then again begins pressing Karen to think of herself; to let him parlay Mike’s presumed tragedy into better things for her—and him. “Take it easy on the makeup,” he calls out to her as she withdraws to change for her next number, “and if you’ve got a black dress, it’s good!”

But Karen’s declared indifference lasts only so long as Leeds’ next phone conversation: his efforts to round up some photographers – even more, his unconcealed glee in this whole turn of events – earn him a slap across the face; but it is rather what comes down the line that really wipes the smile off that same face: “Are you sure?” he demands in evident dismay.

Karen almost collapses in relief at hearing that the plane is still in the air. Leeds sidles up to her, apologising for his behaviour and praising Mike’s skill as a pilot…and then slides smoothly into figuring out how he can exploit these altered circumstances. A final blow-up ends with Karen sending Leeds packing, but only after both his appeal to her cupidity and his savage denunciation of her lack of real talent have failed. (The latter, alas, feels like a set-up for another attempt at “homemaking”…)

Marshall Keats’ hubristic pronunciations get relayed from the newsroom to Ben Gammon, still at Emmy’s apartment, and he is almost as disappointed as Stanley Leeds. He immediately undercuts Emmy’s delight at the altered news, obviously calculating (ibid.) the odds that there still might be a crash to report on; though of course, he gets a story either way. To this end, he also shows his kinship to Leeds in his immediate attempt to take Emmy with him to Idlewild.

Emmy resists, though not for what we might consider the obvious reason – because she doesn’t want to watch a plane crash – but rather because, having spent the evening with Gammon while the crisis was unfolding, she now feels weird about the whole “Mike’s girl” thing.

(Willard will not be pleased…)

Gammon turns on her in his usual petulant way:

Gammon: “Of all the women I have to fall in love with, it has to be one who—who jars me apart while the other guy in her life is getting ready to live or die!”

Sorry, what?

Though she admits that she loves Gammon (whhhyyyyy??), Emmy then veers around in her argument:

Emmy: “What if the plane crashes?”

Gammon: “What if it does? The world’s not going to stop.”

What a lucky girl she is!

Anyway, she sticks to her guns, and Gammon departs alone on the back of what again I have to call a Stanley-Leeds-esque denunciation.

Thankfully – and not before time – we then cut back to the tower at Idlewild, where the controllers are moving all of the other planes in the vicinity out of the way of #214…though they cannot be redirected as such, since Idlewild is now the only airport not “socked in” by the storm. All of these preparations are being made on spec, of course; and the senior personnel are still debating what Mike Trace might do when they get confirmation of his approach from a destroyer, sitting off the coast from Asbury Park.

A controller rather foolishly observes that, under the circumstances, their troubles are over. Reagan points out quietly that there are fifty-seven other planes still in the air over Idlewild, and that none of them can see or hear from #214. Their troubles, in other words, are just beginning…

Down on the field, emergency services are gathering. Behind one barrier, frightened family members are waiting. We see the Kramers and the Lauries pushing their way to the front; Karen Trace is also there; so too Albie Webber and his manager. Nearby, reporters and newsreel cameramen gather; one presenter broadcasts a live update. Suddenly, Emmy turns up—presumably for Gammon’s sake, though she must know he only wants her there for the story. But heaven forfend a woman should listen to her own better impulses when a man wants something from her… Gammon gets her admitted into the press area.

Marshall Keats, meanwhile, having adopted a state of determined optimism, is issuing orders regarding luggage and insurance – and perishable items (two thousand pounds of fish!) – when Felix Allardyce tracks him down and starts pestering him again about his slogan.

Let’s just say that Keats doesn’t like it any better the second time…

Finally, all anybody can do is wait; almost anybody. The plane at the head of the queue of grounded aircraft (“Great Lakes Airlines”) suddenly radios the tower, drawing a reprimand before it hastily explains that a small private plane just taxied past it, apparently planning to take off!

There’s always one, isn’t there? This must be the aviation equivalent of those people who run traffic-lights when everyone else stops to let an ambulance through.

The small plane apparently receives the furious transmission from the tower, because it pulls up—right in the presumed landing path of #214.

And again—here we almost get the aviation version of all those scenes where a car-engine just won’t start—with the small plane struggling – and failing – to remove itself from the runway.

At this point, #214 is at only 300 feet and descending fast; its angle of descent has it coming in at right angles to the small plane sitting across its runway. With little time left – we might even say, no time at all – the only thing the emergency services can do is throw a spotlight on the obstacle and hope for the best…

It is difficult to predict how the casual viewer might respond to No Time At All. It is a film probably best appreciated by those with the appropriate background knowledge: of how television drama was produced in the 1950s, and the circumstances which brought together this odd and eclectic cast—which, by the way, also includes Shepperd Strudwick and Regis Toomey in important supporting roles, and appearances by Richard Crane, Mary Beth Hughes and Jack Mulhall, plus (inevitably!) Bess Flowers in a bit-part.

(Playhouse 90 itself was hosted by Everett Sloane, who introduces the program at the outset.)

The cast, ultimately, is better than the film that contains them, which strains a bit too hard to give all the name-players something to do. The central romance – or “romance” – between Emmy Verdon and Ben Gammon is unconvincing at the outset, and only becomes more exasperating as it develops. Conversely, the scenes between Stanley Leeds and Karen Trace are probably the most interesting aspect of what we might call the domestic side of the film, because both Jack Haley and Jane Greer are playing against type. On the technical side, Shepperd Strudwick as Reagan projects quiet competence in the face of Keenan Wynn’s bullying and bluster as Keats, while Regis Toomey as Joe Donaldson does well with his jargon-heavy dialogue.

But as I said at the outset— The most striking thing about No Time At All is surely how early in the disaster cycle it appeared. Such a calculated inversion of the tropes of the genre is startling; yet you can certainly understand where Charles Einstein was coming from. By 1957, when he wrote his novel – only three years after The High And The Mighty – the situation of airline passengers sitting and fretting – and having flashbacks – while their flight-crew fights to manage an emergency had been done. (Not that this stopped anyone in 1958…or has yet stopped anyone, thank goodness!) The idea of showing how such an emergency would affect everyone else was a clever way of shaking up a scenario that was already threatening to become moribund.

Of course, it can be fairly argued that all Einstein did was take the soap that usually plays out inside the plane and relocate it to the ground; and in fact, my main criticism of No Time At All is that there is too much soap and not enough airline personnel trying to manage the crisis; though with the disappearance of the plane from radar, that isn’t an unreasonable distribution of drama. Furthermore, this balance does shift over the final section of the film, as it should.

I can understand that there will be those who won’t get much out of No Time At All – perhaps the same people who object to the classification of Airport as “a disaster movie” because only one person dies and the plane doesn’t crash – but for those of us who love the genre and the people who tweak it, this is a fascinating little film.

Footnote: I have belatedly realised that this film also belongs over at Spinning Newspaper Injures Printer.

♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦

This review is part of the Disaster Blog-A-Thon: click below for more!

“…an overly sensitive Charles Bronson…”

I’ll take “Phrases I Never Thought I’d See” for $2,000, Alex.

Thanks this awesome contribution to our blog-a-thon!

LikeLiked by 1 person

😀

This is one of several small roles at this time where we find Charlie – from our perspective now – out of character. He’s actually very classy here! – not that anyone appreciates it…

Thank you for the awesome Blog-A-Thon! 🙂

LikeLiked by 2 people

In “The Sandpiper,” Bronson is an artist who sculpts a bodacious nude bust of Liz Taylor. But the improbable thing is that he gets beat up by Richard Burton!

LikeLiked by 1 person

In Pat And Mike he gets beaten up by Katharine Hepburn. 😀

LikeLiked by 1 person

In the (awful) “4 for Texas,” he gets killed, but I forget by whom. Hard to believe Robert Aldrich made this movie.

LikeLike

Great post! Loved your overview of Playhouse 90 and live TV in the 50s. These productions were chock full of great Hollywood stars and character actors playing interesting roles, and this is no exception. Looking forward to seeing this in the near future!

LikeLike

Welcome, Christopher, and thank you! I hope you enjoy it. 🙂

Doing this I discovered that there are many of the TV broadcasts of the time on YouTube, (including the problematic Playhouse 90 adaptation of Judgement At Nuremberg), and I’m looking forward to exploring those more thoroughly.

LikeLike

Don’t forget Requiem for a Heavyweight….

LikeLike

You being Australian probably don’t remark him, but the plane spotter is played by Howard McNear, more famous for being Floyd the barber in the Andy Griffith Show.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ah! The name was vaguely familiar but I can’t say his face rang any bells. (All I know about TAGS is what I’ve picked up from pop-cultural references.)

LikeLike

I don’t know civil aviation procedures of the 1950s, though transponders don’t seem to have been universal yet. These days I’d expect the pilot to turn back, squawk 7600 if the transponder’s still working (which it usually is), fly a standard hold round the field until they got light signals, and make a priority landing. Air traffic control would be moving other aircraft out of the way as soon as they knew what was going on.

I have to assume that in the 1950s half the men in the US vanished for some reason, so most women took what they could easily get… though even on a crude economic calculation, an image of “girlfriend of dead hero” is surely worth more than “callous harpy who abandoned dead hero to marry reporter”.

LikeLike

Transponders were not compulsory in civil aviation for a scarily long time after this (just by coincidence, while reading around this I found an article from 1969 arguing why they should be). And there’s a fairly comprehensive explanation for why the pilot doesn’t turn back, including the storm really hitting Florida just after his takeoff. Under the circumstances he presses on to Idlewild because they’re the only ones likely to be expecting him.

The idea that you were supposed to “take what you could get” when this is what you could get…ugh!

Gammon’s actual story is most likely to be—

…

…

…

…

SPOILER ALERT!!

…

…

…

…

“Hero pilot snogs ex-wife.” 😀

LikeLike

Well, I know what I’m watching on Saturday afternoon. I always enjoy the programming from the Golden Age of television due to all of the amazing creativity involved and look forward to No Time At All.

LikeLike

Hi, Patricia – thanks for visiting! I hope you do (or did) enjoy it. 🙂

LikeLike

When old-timers like me talk about how good the television anthology series of the 1950’s (PLAYHOUSE 90, THE ALCOA HOUR, FOUR-STAR PLAYHOUSE, THE U.S. STEEL HOUR, et al.) were, this is the kind of thing we’re talking about. (Unfortunately, many of these “prestige” efforts were drek, too.) The thing that strikes me about chapterplays like “No Time at All” is how much tension and drama can be mined out of a situation without the need for explosions or crashes or fast chases or brawls, nor any startling special effects. I’m afraid that the most recent generations of movie-watchers would find this film quite dull. (I have a rule of thumb; when someone tells me how great a new movie is, and I ask him why it’s so good, and he responds something to the effect of, “The special effects are fantastic!”, then it’s a film I’ll skip, thank you.)

You’re right, Lyz, “No Time at All” is a credit-watchers abbondanza. Fortunately, the players were from my era so I could identify them. One point: the actor who portrayed Albie Webber. I’m sure that was Richard Crane. I know that the IMDb entry for “No Time at All” lists Richard Crane as playing “Pilot”, but a video of “No Time at All” is available on line. Yes, I did fast-forward through much of the film, but I paid close attention to both the prizefight sequences and to the last twenty minutes, when the part of a pilot (outside of Mike Trace) was likely to be seen. I saw no other pilot characters, and I took a good look at the Albie Webber character when he confronts Wolf Hagen in the dressing room. That’s Richard Crane, former star of television’s ROCKY JONES, SPACE RANGER, and he had the physique to play a prizefighter.

I had never heard of “No Time at All” until you reviewed it. That’s one of the unsung services you do all the time, my friend: introduce us to cinema that we would want to see, but never would have known about. Much obliged!

LikeLike

Oh, and didn’t I tell you how sweet the pre-FRIDAY THE 13th Betsy Palmer was?

LikeLike

It’s great that so many of these productions are turning up on YouTube and other sources. And my goodness, even if they are technically drek, the casts! I’ve expressed my preference for rubber hand-puppets over squillions of CGI before, so you’re preaching to the choir. 🙂

Thanks so much for that! I could find no cast information at all outside of the IMDb listing, which is strange and frustrating. I knew that Richard Crane was Rocky Jones, but I didn’t recognise him here. I will edit that bit up above.

I hadn’t head of this either until very recently: it must have turned up on someone’s list of disaster movies, or maybe just plane movies. In a way it was frustrating, as every time I think I’ve finished the 50s they keep pulling me back in!

You did! – though mind you, in context I think she’s a little too sweet here. (Put it this way: I’m sure no-one would have blamed her if she’d hit William Lundigan with a machete!)

LikeLike

I was sold on this idea anyway, but then you mentioned one of my all-time faves Keenan Wynn. Thanks for the introduction to this film – I know I’ll enjoy it very much.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi, thanks for visiting! Keenan’s disaster and killer animal movie credentials mean that I see plenty of him, of course. I hope you do enjoy this when you get a chance to watch it.

LikeLike

I must be the only fellow who’s first and most lasting recollexion of Keenan Wynn was from his stint on the one-season television series TROUBLESHOOTERS (1959-60), which starred him and Bob Mathias as the two-fisted operators of a construction company.

Would you mind passing me that bottle of Geritol, Lyz?

LikeLike

Scary, isn’t it??

I don’t think we ever got Troubleshooters here (and frankly I’m struggling to imagine Keenan Wynn in the role you describe!). I guess that’s another to look out for online.

LikeLike