Director: William A. Wellman

Starring: Pat O’Brien, Dick Powell, Lyle Talbot, Ann Dvorak, Hugh Herbert, Arthur Byron, Donald Meek, Arthur Hohl, Guinn Williams, Nat Pendleton, Ward Bond, Joe Sauers (Joe Sawyer), John Wayne

Screenplay: Niven Busch and Manuel Seff

There’s very little science in this “science movie”—but that’s kind of the point.

I was drawn to College Coach by its short, onscreen menu synopsis, which informed me that it involved Dick Powell having to “choose between chemistry and football”, which sounded unlikely on all counts, not to say rather amusing. I was expecting only another short-review, Et Al. candidate; but before we were two minutes into this film I knew it would require more in-depth treatment.

I should probably start this piece by explaining that our sporting arrangements here are quite different from the American model, in that our education system and our sports are totally separate entities. This is not to say that schools and universities don’t have sports and sporting competitions, but they are minor and self-enclosed; they are not where our professional sportspeople come from, nor do we really have such a thing as a “sports scholarship”. Consequently, taking an interest as many of us do in sports of all kinds, worldwide, we often gaze upon the American college system with raised eyebrows or a furrowed brow. Sometimes both at once, which isn’t easy.

The magnitude and the seriousness of college sports are rather staggering at this distance, but even more so (or at least, this is the impression we get) is the pre-eminence given to sports over education, in an explicitly educational setting. Worrying stories of covered-up abuse tend to support this point of view, fairly or unfairly.

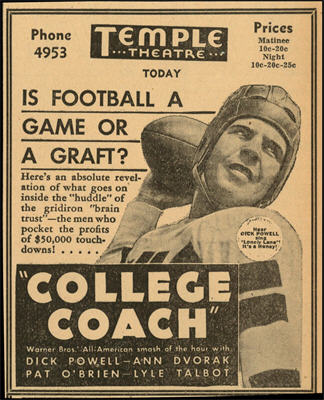

However, I bring up these matters purely to explain the mindset with which I approached College Coach, which is about the earliest days of the current arrangement, when college football was gaining ground not only in its own right, but as a source of revenue, and in the process shifting from an amateur to a more professional standing—if not overt, actual professionalism: a situation which carried with it new temptations and opportunities for corruption. It is significant, I think, that both the advertising for College Coach and a number of contemporary reviews treated the film as an exposé of college football:

—but that is not the attitude of the film itself, which rather takes a stance of, “This is how things really are—and if you don’t like it, you can bite me.”

College Coach opens with a meeting of the Board of Trustees of Calvert University, and the revelation that the institution is in deep financial trouble. One of the trustees knows exactly where the blame should be placed:

Trustee: “Our big mistake was financing the new science laboratory and the Special Chair in Chemistry.”

In the middle of the meeting, another trustee, Seymour Young (Arthur Hohl), wanders off to turn on the radio coverage of a college football match, attended by “almost 100, 000 fans”—and has a brainwave: if Calvert could build a winning football team, it could solve its financial problems and raise new revenue. He proposes that Calvert try to secure the services of the most successful coach in the game:

College President: “Don’t be ridiculous! He’s under contract to Northern.”

Trustee: “Sure—but a contract doesn’t mean a thing to him.”

Young makes a strong financial argument, and the other trustees begin to warm to the idea; but Dr Philip Sargeant (Arthur Byron), the President, is against it on moral grounds:

College President: “I’m against having this man Gore at Calvert on any basis. He’s a headline-hunter—an unscrupulous, high-pressure showman. I don’t want to see our students turned into tramp athletes, stage-struck performers in his Saturday circus. Why, he’s professionalised every college that’s employed him! Surely we can pay for our laboratory without resorting to the things he stands for?”

Guess who wins that argument?

So Coach Gore (Pat O’Brien) – no first name, just “Coach” – transfers from Northern to Calvert, bringing his entire circus along with him, and gets to work building a winning football team: a process that involves planting a number of “ringers”, professional athletes posing as students, at Calvert. Of course they have to enrol – and pass. Cue an extended sequence of Gore and the faculty advisor making sure that the imports are placed in classes that will make the least demands upon their time and intelligence…

This is the beginning of Gore’s manoeuvring, but it’s far from the end. We watch him using his position at Calvert to feather his own nest, including a piece of unethical financial manipulation based on insider knowledge that will make him a small fortune when (on the back of his team’s success) the college commits to building a new stadium. We also watch him doing anything it takes to make sure his team does win—including resorting to on-field tactics that (in those pre-protective gear days) result in the death of the opposition’s star player:

Commentator: “It may not be sportsmanship, but it’s football.”

Really, by the time Gore gets through, the only thing missing from this scenario is performing-enhancing drugs. (And of course, there’s always that new chemistry lab…)

So where does Dick Powell come into all of this?

***********************

Pardon an interruption.

College Coach is largely forgotten today, but as far as it is remembered, it is for its bit-players. One of them is Ward Bond, who has a tiny role as one of Gore’s assistant coaches; another, as one of the football players, is long-serving movie tough-guy, Joe Sawyer—still spelling his surname “Sauers”; while Dave O’Brien has a blink-and-you’ll-miss-him bit as a tennis player. And finally – in the last of his many unbilled appearances – we have John Wayne, who gets a couple of lines exchanging greetings with Dick Powell’s character. This meeting began a strong friendship between the two which lasted for many years (and which, tragically enough, led to The Conqueror):

***********************

To resume:

Dick Powell plays Phil Sargeant, Calvert’s quarterback and captain. He is also (as his name indicates) the son of the College President, from whom he has learned a strict moral code— which will cause a variety of problems for himself and others before the story is over. Phil likes football, but it’s secondary to his main passion, chemistry, in which he intends to have a career.

(And because this is Dick Powell we’re talking about – 30s Dick Powell, as opposed to post-war Dick Powell – Phil’s other hobby is music. We get one song from him, “Lonely Lane”.)

Phil starts out reassuring his father and Professor Spencer Trask (Donald Meek), who is occupying that newly-created Special Chair of Chemistry, on that point, insisting that he can do justice to both chemistry and football—but when Gore barks, Phil responds like everyone else. Matters come to a head when the Calvert team is on the road for a month, with no time left to the players for study. Phil returns to the university to confront an exam for which he has done no preparation, and ends up turning in a blank paper.

Yet when the exam results are posted, he receives a ‘D’, a passing grade. So does the team’s star running-back, the obnoxious and egotistical but talented Buck Weaver (Lyle Talbot), who likewise handed in a blank paper, but with a broad, cocky grin in place of Phil’s white-faced unhappiness. Later, when there’s a crackdown, Weaver will resort to buying a copy of the exam paper in advance, a manoeuvre that wins him a hearty handshake from his coach. Phil, however, has had enough:

Phil: “That mark was a joke, Gore, but it wasn’t funny. Not when a lot of fellows in this school studied night and day and knew something – but flunked – just because no coach had them put on the privileged list.”

Gore: “You couldn’t play if you weren’t eligible.”

Phil: “Great – but who’s going to get me passing grades when I go out of here and try to earn a living? I’ve seen your tramp athletes – a flock of Saturday afternoon headliners when the song-and-dance is over – ratting around in some pro-league, clerking in hand-out jobs. Well, maybe I’m just a sap, but I didn’t come to school to kick a football and get my name in the papers—I came here to learn something!”

Phil quitting is the first of a string of incidents that begins to undermine Gore and his approach to football. The captain-quarterback’s absence hurts the team and it starts to struggle, prompting the tactics that end in the opposing boy’s death. Dr Sargeant warns Gore that he will do everything he can to have him removed, and though he doesn’t succeed in that, his attempt to expose Gore’s methods ends in a number of the other teams in Calvert’s conference – of which Calvert become champions in 1932, despite / because of Gore’s tactics – refusing to play them anymore. It also means Gore loses his “ringers” and has to play actual students, sending the team into a losing streak that threatens to ruin his secret financial deal, which requires a winning team. Meanwhile, outside of football, Gore’s marriage to the long-suffering and much-neglected Claire (Ann Dvorak) starts to fall apart…

And you know what, folks?

This film wants us to feel sorry for Gore.

And, what’s more, it manipulates its plot-threads so that everything rides on one big game, “the Shipley game”: if Calvert wins, the trustees will commit to the new stadium, making Gore’s fortune. If not, no stadium—but no Special Chair of Chemistry, either:

Trask: “My Chair in Chemistry depends on college funds—and unfortunately, those seem to depend on football revenue.”

Phil: “Why, this work with you is all I came to college for! Your job – my life’s ambition – everything a university is supposed to stand for! – all goes by the board…”

This revelation sends Phil running back to the team, while Claire Gore manipulates Buck Weaver into also rejoining. The two show up just in time to turn around the team’s performance, and so give the film a happy ending—and no, of course I don’t mean Professor Trask keeping his job—but rather, Gore not just cashing in on the back of “the Shipley game”, but being enticed to break his contract with Calvert and go to Shipley in exchange for an even bigger salary and a lot more perks:

Gore: “You say the players won’t even have to go to classes!?”

We’re used to pre-Code films in general, and Warners films in particular, being cynical, but this one just about takes the cake in the way it treats so much of what Gore says and does as a joke. For example, there’s a moment when Gore unwisely remarks that, “We’ll make them look like amateurs” – forgetting momentarily that all the players in college football are supposed to be amateurs; another when Phil misses a session because he’s – gasp! – studying, provoking Gore into an angry, “What does he think we’re paying him f—“, until his assistant nudges him in the ribs.

“He’s not only a menace to sport, but a destroyer of every ideal held by this college!” declares Dr Sargeant of Gore—but while overtly positioning the indignant academic as its moral centre, as it does Phil Sargeant as a young man with his head on straight and his priorities sorted out, College Coach puts most of its weight into its tactic presentation of Gore as a realist ahead of his time.

It left me feeling a bit sick, actually.

It seems to me likely that Phil Sargeant’s choice of career in College Coach was prompted in a sort of word-association way by the real-life career of Knute Rockne, who made the opposite choice from Phil’s (and who, in what goes beyond mere irony, would be played seven years later, in Knute Rockne, All American, by Coach Gore himself, Pat O’Brien). The one tiny silver lining to be found in this film is its all-too-brief glimpses of Phil doing SCIENCE!!— and the way that, consciously or unconsciously – and I think it was unconscious, which makes it even more interesting – science is presented as the thing most diametrically opposed to Coach Gore and his dirty tactics.

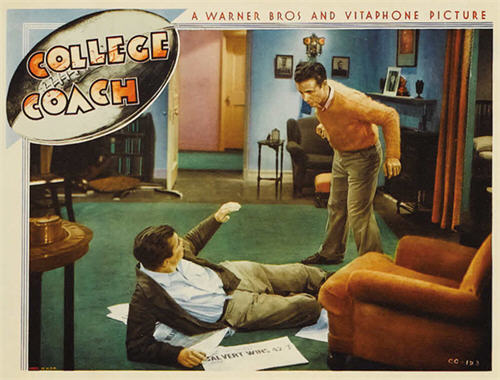

Footnote: The advertising art for this film is weird. Pat O’Brien hardly appears in it, and Ann Dvorak looks like the third point of a romantic triangle, caught between Dick Powell and Lyle Talbot. Alas, though not surprisingly, there’s no science; so up above, I’ve gone with Phil Sargeant punching out Buck Weaver—and if you’d just spent 70 minutes in the company of the abhorrent Weaver, like I have, you’d thank me for it.

Dick amongst his test tubes.

I just want to thank you for being on the others side of the planet tonight to make the latest round of insomnia more palatable. Not shorter, lol, just less dull.

Boy, does this seem like it would be even more relevant right now, given some of our current scandals.

LikeLike

And what a fabulous cast, need to hunt this one down as I am fascinated by pre-code filmmaking.

LikeLike

Ouch, sorry to hear about the insomnia! 😦

Yes, I always find these early sports films fascinating in an evolutionary sense. The NFL started, what, early 20s? So you can see here the flow-on effect from the establishment of the professional competition.

It has got a great cast but be warned, there is a LOT of Lyle Talbot!

LikeLike

and once again, there is nothing new under the sun.

LikeLike

I remember in Phoenix, Arizona, about 30 years ago, the ASU football coach was fired due to alleged excessive violence. The paper ran the headline, “KUSH FIRED!” in large letters. For the next two weeks, war could have been declared, and nobody in Phoenix would have cared. They just wanted their Kush back.

LikeLike

Yeah, we’re supposed to be obsessed with sport here but we’ve got nothing on you guys. As I mentioned, your whole college situation is alien to us in all respects; the magnitude of the thing itself and the level of interest we find rather bewildering.

LikeLike

Meanwhile I have a hole in my mind where “appreciation of sports” is meant to go: I literally cannot understand the appeal of cheering for a team that you’re not a player on. So practically everyone looks “obsessed with sport” from where I’m standing. 🙂

LikeLike

Same here. I can watch and enjoy them, especially live and in person, but when I tried to follow the NFL seriously in high school so I’d fit in better, I just couldn’t do it. I also know about what colleges think is most important: my sister had schools promising her the moon if she’d play basketball for them, and went to tournaments in Switzerland and Lyz’s neck of the woods; while I’m still paying my student loans 20 years later, and the closest I’ve been to leaving the country was a trip to Oahu.

Still, I got a few amusing stories from my years living in Omaha; even die-hard college football fans look at Cornhusker fans as rabid maniacs. Sadly, the stories from here in Texas regarding high school football fans and player parents are not funny at all.

LikeLike

We do this weird thing where we present ourselves to the world as a bunch of sports-obsessed, beer-swilling rednecks (stemming, I guess, from a twisted sort of psychology where we’re ashamed of the wrong things), but it’s really not the case. Trust me, we gawp at you in disbelief. 😀

I don’t have any trouble appreciating sports, but in their place: the whole tangle-up with the educational system just seems wrong in so many ways. (And the cheerleading thing, that’s just creepy.)

LikeLike

Pingback: Spinning Newspaper Injures Printer | and you call yourself a scientist!?

Pingback: Et al. – Latest entries | and you call yourself a scientist!?

Pingback: Bits and pieces « The B-Masters Cabal

You want to get creeped out by cheerleading, check out the outstanding novel Dare Me, by Megan Abbott.

Ahhh, yes, college sports. Where young men are pounded to a jelly in their formative years, then discarded. We’re just getting a discussion started about the inherent racism behind a lot of sports, especially football (many athletes are offered huge scholarships, but suffer tons of injuries, especially repeated head trauma. Since many Black athletes are steered towards these scholarships…)

LikeLike

Thanks, but I think I’m sufficiently creeped out already. 😀

Our sports aren’t as impact-heavy as yours but our administrators are keeping a close eye on your studies into the long-term effects of concussion, and have introduced some erring-on-the-side-of-caution rules about concussion injuries.

LikeLiked by 1 person

If it helps any, a lot of us are equally appalled at the situation with college sports and the commoditization of young athletes, especially black athletes, in service of the institution, even in less dangerous sports. Unfortunately it’s so entrenched that a lot of universities would collapse if the system went away, so they’ll fight tooth and nail to make sure that doesn’t happen. Me, I think if a school wants to mount a professional sports team to underwrite it, then do that; don’t maintain the charade that these kids are students unless they actually want to be.

LikeLiked by 1 person

And it’s one of many uncomfortable things about this film that it shows the beginning of that process, and an institution walking into it with eyes open—and then pressuring its students into having to give sport at least as much time as their education.

LikeLike

>>> a process that involves planting a number of “ringers”, professional athletes posing as students

Well, what do you know, THERE’S the explanation for all of those movies full of “too-old” college students…

LikeLiked by 1 person

I dunno…most of them look a bit too long in the tooth for college football…

LikeLiked by 1 person

Off-topic (and probably nobody’s still posting on this page anyway), an “obvious” explanation for having older-than-teenagers play teenagers dawned on me: So moviegoers can ogle the cheerleaders and other scantily dressed “teenage girls” with a minimum of awkwardness.

Then again, back when the older-actor trend was more prevalent, people didn’t get quite as bent out of shape about adults, uh, appreciating teenage sexuality as they do now so it wouldn’t have been much of an issue back then (I’m not saying that’s a “good” thing, it just appears to me to be an objective fact; maybe I’m wrong anyway) so…well, whatever.

LikeLike

I suspect it’s more simply that once they’re over 21 you don’t have to worry about child labour laws, pushy parents, or the other problems that come with using child actors.

LikeLike