“I’m right where I’m wanted. I’m home. You see, this is the room where Carolyn had her baby before she ran away. And the children— They wanted me to see this, so I would know that this is my home…”

Director: Jan de Bont

Starring: Lili Taylor, Liam Neeson, Catherine Zeta-Jones, Owen Wilson, Alix Koromzay, Todd Field, Bruce Dern, Marian Seldes, Virginia Madsen, Michael Cavanaugh

Screenplay: David Self, based upon the novel by Shirley Jackson

Synopsis: Having devoted eleven years of her life to nursing her bed-ridden mother, Eleanor Vance (Lili Taylor) is stunned and outraged when she learns that not only has the apartment which they shared been left away from her, but that her sister and brother-in-law want her to vacate it as soon as possible – even though she has nowhere to go. In the wake of a violent quarrel, Eleanor receives a phone-call which directs her attention to an ad in the paper, calling for subjects for an insomnia study – and offering $900 a week, plus room and board. Dr David Marrow (Liam Neeson) argues with the head of his department over his planned experiment into the fear response, for which he is recruiting subjects under the guise of insomnia research, on the grounds that their awareness would compromise his study. With his assistant, Mary Lambetta (Alix Koromzay), Dr Marrow selects those individuals he judges the most suggestible… Eleanor arrives at Hill House, a palatial, sprawling mansion in the Berkshires, and is admitted by Mr Dudley (Bruce Dern), the caretaker, and his wife (Marian Seldes), the latter of whom leads Eleanor to her enormous bedroom. The next arrival is Theo (Catherine Zeta-Jones), an artist from New York. The two women explore the extraordinary house, examining the many carvings representing children and babies, soaring metal doors carrying an engraving modelled upon Rodin’s “Gates Of Hell”, and a huge, glowering portrait of the house’s builder, Hugh Crain. Throwing open two more doors, they stumble over another participant in the study, Luke Sanderson (Owen Wilson). Shortly afterwards, Dr Marrow arrives with his assistant, Mary, and the study’s final subject, Todd Hackett (Todd Field). Over dinner, Dr Marrow explains to the group that his study is intended to try and understand the psychology of insomniacs, with the hope of finding common underlying factors. Later, as the group gathers before the fireplace, he distributes a series of tests to be completed, explaining that isolation is vital to the study, and that there are no phones and no televisions in the house. Eleanor asks the history of the house, and Dr Marrow explains that it was built one hundred and thirty years earlier for the family Hugh Crain expected to have with his wife, Renee; but that none of their children survived and Renee, too, died young, after which Crain became a recluse; although at times the sounds of children were heard coming from the house… As the group digests this story, Mary exclaims abruptly that there must be more to it; that there is something about the house— Nearby, unseen, a key on a clavichord begins to tighten—and a wire snaps, slashing her across the face… As Todd prepares to drive Mary into town for medical attention, Dr Marrow hands him the key to the gates, relocking the padlock after they have gone. As they walk back to the house, Dr Marrow tells Luke that there is in fact more to the story than he has so far revealed: that Renee Crain committed suicide. He asks Luke not to tell the others – but Luke does so as soon as he sees them. That night, Dr Marrow records his notes, commenting on the suggestibility of his test subjects and their reactions to the stories – and his reliance upon Luke repeating what was told to him about Renee. As she lies sleepless, Eleanor thinks she hears a child’s voice whispering her name – and then becomes convinced that the carved faces in one of the wooden panels are looking at her. Later, she is woken by a banging noise and instinctively responds, as she always did when her mother called for her in the night – and then realises where she is. But the banging does not stop: it grows louder, and is accompanied by a growling noise. At that moment, Theo cries out for Eleanor, who runs to her. They crouch together on the bed, gasping in terror as something tries to force its way through the locked bedroom doors…

Comments: Some houses are born bad, says the tagline for The Haunting. And so are some movies, retorted just about every critic who reviewed it – and why should I buck the tide? On the sliding scale of botched remakes, The Haunting ranks pretty high. Its cinematic sins are many and varied, but to my mind the greatest of them is that it seems so disrespectful of its source – both the novel and the film. There’s a sense of impatience with the material about this film, as if its makers undertook the project in order to show people how this sort of thing should be done. Of course, the last time we looked at film made so that its director could demonstrate the right way of doing something, it was John Boorman expressing his disapproval of The Exorcist by way of The Heretic…and we all know how that turned out.

But maybe I’m being unfair to Jan de Bont and David Self here. It may be, rather, that (as a number of commentators have suggested, including one or two of my colleagues) the two of them got confused between Shirley Jackson’s The Haunting Of Hill House and Richard Matheson’s Hell House. I mean, hey— Hill, hell, what the heck?

And it’s even bigger on the inside.

It is, in any event, preferable to think that some such confusion did occur, than that the makers of The Haunting honestly thought that the correct way to handle one of the most subtle horror stories ever told was to turn it into a ridiculous, overblown, CGI crap-fest. It speaks volumes that the film this mess of a production most reminds me of is neither the original version of The Haunting, nor The Legend Of Hell House, nor any of its subsidiary influences like The Shining, but—Amityville 3-D. Only that film is a lot more fun.

Set against a storm of special effects nothingness, there is little that the cast of The Haunting can do. However, while the acting here is uniformly uninspired, I tend to blame this chiefly on the script; it’s hard to build a good performance on bad dialogue, and this film has bad dialogue in spades, particularly during the early, expository scenes.

(And then there’s the film’s climax…but we’ll get to that presently.)

However, in the end I think the overriding problem is the film’s conception of Eleanor. Gone is the prickly, defensive, self-pitying victim-villain of the original story, so well interpreted by Julie Harris. Here, all Eleanor’s complexities – her darknesses – have been stripped away, leaving us with a far more conventional, and far less interesting, victim-hero. This weakening of its central character is terribly damaging to the story, and particularly to the other characters, who are, or should be, revealed and defined through their interaction with her; and this in turn creates a fundamental hollowness that even the film’s overpowering soundtrack and special effects cannot disguise – no matter how hard they try.

The overwrought tone of The Haunting is struck right at the outset, as poor put-upon Eleanor is sneered at and abused by her wicked step-sister, Jane (Virginia Madsen—why!!??) and brother-in-law, not to mention their revolting brat of a child, and we learn that although Nell has devoted most of her life to being her long-ailing mother’s live-in carer, Mommie Dearest has cut her off without even the traditional shilling. Now, I’m not going to object to the grotesque injustice of this (something similar once happened in my own family, as a matter of fact), but I confess, I am rather puzzled over the terms of the will, which seems, based upon the dialogue, to have named an executor but no heir. Or if Jane and Lou are the heirs, why all the fuss about Lou being named executor?

Oh, boo-hoo. I’ve seen this film six times.

In any case, the point is that the eee-vil relatives, in spite of knowing that Nell has no money and nowhere else to go, have every intention of selling the apartment right out from under her in the shortest possible time. (Making mystifying their complaint that she’s two months behind with the rent – what rent?) Adding insult to injury, Jane “gives” Nell their mother’s ancient little car as her share of the estate; and then, having stuck the knife in, she gives it a sisterly little twist by inviting Nell to come and be her live-in housekeeper – upon which Nell kicks them all out.

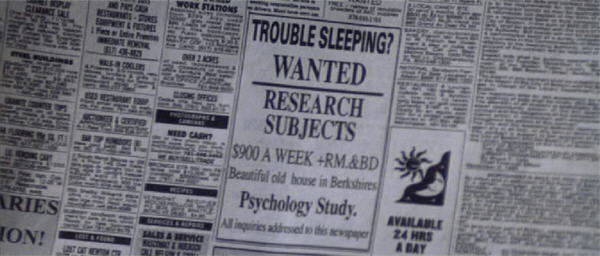

So understandably, when a phone-call comes out of the blue drawing Nell’s attention to an ad in the paper, offering money, room and board in exchange for participation in an insomnia study, she is more than receptive.

We cut to “the university” (unspecified, for reasons that will soon be made clear), where Dr David Marrow and his assistant, Mary Lambetta, are choosing the subjects for the study in question, and learn that along with the insomnia and the accompanying personality disorders, what Marrow is particularly looking for is people who are suggestible.

And then we discover The Awful Truth: Dr Marrow isn’t studying insomnia, or only as a side-line; what he’s really studying is fear.

All is revealed during an argument between Marrow and the head of his faculty, a scene that tends to leave me with a bad case of exasperated giggles, as we are given another blinding insight into Hollywood’s view of How Science Is Done when Marrow justifies misleading his subjects via one of filmdom’s Great Science Lines:

“You don’t tell the rats they’re actually in a maze!”

“These are, granted, minor considerations…”

See, here’s the thing— An experiment of this kind is not something that a faculty head would simply shrug at. Of course, neither is it an experiment that a scientist would actually conduct – even if we put the morality of it to one side for the moment – and here’s why:

- No-one would publish the results.

- No-one would ever give that scientist another grant.

- No-one would ever give that scientist another job (ditto the faculty head).

- Lawsuits would inevitably follow, and probably criminal charges too – given the nature of the experiment, at least reckless endangerment and possibly negligent homicide.

(Oh, come on – like that’s a spoiler!)

But heigh-ho, this is Hollywood, where everything’s made up and the points don’t matter. So while Marrow’s boss shakes his head over all this and replies (and rightly) that what Marrow is planning on doing is completely unethical and irresponsible, apparently this is no big deal at this particular university, as the next thing we know Nell is driving up to the gates of the sprawling Berkshire mansion known as Hill House.

(Fun fact: the exterior scenes for this film were shot at Harlaxton Manor in Lincolnshire, which these days is the British campus of the University of Evansville.)

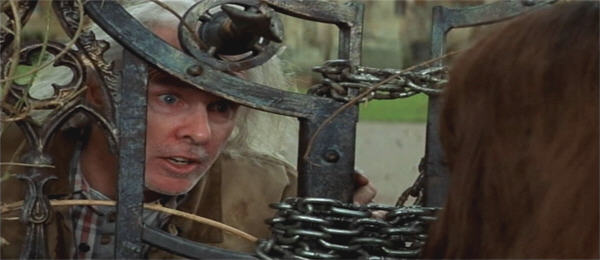

Climbing out, Nell finds the gates heavily chained and padlocked. She is tugging at them when she is startled by the caretaker, Mr Dudley, played by a cameoing Bruce Dern (enough to startle anyone, I should think), who after some grumbling unlocks the gates so Nell can drive in. At the front door, she knocks and calls for Mrs Dudley, then realises that the door is open and steps inside—and the movie goes to hell house.

AHHHH!!!!

I’ve always considered that the mark of an unsuccessful horror film is that, as the credits roll, you find yourself wondering what on earth the survivors were going to tell the police?—in other words, disbelief has not been suspended. It is a measure of The Haunting’s overall credibility that it becomes impossible to take any of it seriously, still less suspend disbelief, as early as its 12th minute—which is when we get our first good look at what is supposed to be an actual 1870s mansion.

Impressive as it may be purely as a piece of design, as a convincing backdrop the interior of Hill House is the ne plus ultra of absurdity. Each feature we see is more ridiculous than the last, the entirety bearing far more resemblance to a particularly intricate carnival funhouse than to a real house designed and built by anyone, in any place, at any time.

On the other hand, the design of the house is fully in keeping with the film’s attitude towards its supernatural manifestations which, from the moment of their first appearance, are thrust into the viewer’s face with the relentless cruelty of the schoolyard bully. The cumulative effect is wearying in the extreme – and, perhaps more to the point, not the least bit frightening.

As I have confessed before, I’m rather susceptible to haunted house stories, which for no reason I could articulate usually manage to push my buttons. The Innocents, for example, scares me half to death – cold shivers, cringing back in my chair, the works; while even the good old Amityville Horror still manages, after all this time, to provoke a series of nervous jumps. So if you’ve made a haunted house movie, and the most extreme physical reaction you can get out of me is a regular glance at my watch— EPIC FAIL.

Cosy little shack.

Nell follows a pounding noise to the kitchen, where she is again understandably startled, this time by the abrupt appearance of the housekeeper, Mrs Dudley, who leads her to her room, a journey hampered by Nell stopping to give the viewer a look at some of the film’s signifiers: the huge fireplace, guarded by stone lions; the stone griffins on the staircase; and the enormous portrait of Hugh Crain at the top of the stairs (and you kind of have to admire a man who chooses to display himself as a glowering monster). We learn that Nell has been assigned “The Red Room” (!), and that the study group are the first visitors to the house since Hugh Crain died.

(It is further indicative of the film’s failure to engage that I immediately began to wonder things like, if the house has been empty for about a hundred years, who installed the electricity? Not to mention the plumbing. Come to think of it, who owns the house? And who exactly prepared it for the arrival of the visitors, given that there is barely a speck of dust anywhere in its TARDIS-like interior? And who’s paying for this little jaunt, anyway…?)

The camera pans around, displaying a bedroom of dimensions roughly similar to those of Westminster Cathedral, and giving us the first of many, many, many, many looks at the pointy wooden things which are for no discernible reason hanging over the bed. We also get our first dose of the film’s ubiquitous baby imagery, as Nell, after one look around, zeroes in on the carvings over the fireplace, which—

I said that this film isn’t scary, but that’s not to say it isn’t creepy. To be perfectly honest, I’ve always been in sympathy with Homer Simpson and his, “Uhhuhhuhhuhhuh….babies” reaction. A particular baby is fine; “babies”, collectively, not so much. It will presently be revealed that there are duelling presences in Hill House, one malevolent, the other benign; and while the activities of the former left me entirely unmoved, the latter – manifesting in the form of swarms of disembodied small children – induced uncontrollable shuddering.

You don’t expect to make it out alive with an attitude like THAT, do you?

Nell, however, beams delightedly at the riot of wooden faces and starts gushing over how much Mrs Dudley must love working in such a beautiful place. Ignoring these effusions, Mrs Dudley makes a statement of her own duties and what she will and will not do for the guests. This is one of the few scenes in this film that is directly reproduced from the original version (and the novel), and it serves as a fair summary of the distance between them.

The first Mrs Dudley’s recitation of how no-one will come near the house, so there will be nobody to help – in the night – in the dark – is one disturbing detail amongst an accumulation of many, as it slowly becomes apparent that she herself is one of the casualties of Hill House: the over-wide smile with which she concludes her speech is more frightening than anything in this film.

The second Mrs Dudley, however, with her open contempt of the visitors, is far too solidly grounded for the same speech to seem in character. It is possible, I suppose, that Dr Marrow paid her to make that speech; but regardless, there is a cheesy theatricality about her recitation that is embarrassing rather than unnerving.

The next arrival is Theo, in whom what was merely hinted at with respect to Claire Bloom’s character is here blown up out of all necessary proportion as, by way of an establishing speech, she complains volubly about the difficulties she has juggling her boyfriend and her girlfriend. In the wake of Theo’s declaration of her try-sexuality, an uncomfortable Nell flinches away from her touch – which is interesting inasmuch as before too much longer she will be encouraging dead children to play with her hair. Oh, well. Different strokes.

“I don’t serve. I prepare the meals, do the dusting, and frighten the guests by appearing suddenly with a meat cleaver in my hand, but I don’t serve.”

The two women set out to explore, and we get our first look at the following immensely practical household features:

- Twenty-five-foot high metal frieze doors detailed after Rodin’s “Gates Of Hell”.

- A mirror-lined room with a floor of rotating concentric circles.

- A water-filled corridor with ceramic book stepping-stones.

At the metal doors, Nell and Theo pause for a conversation about purgatory that doesn’t seem the least little bit like foreshadowing being awkwardly elbowed in, before pushing open yet more doors and literally running into Luke Sanderson, subject #3. Dr Marrow arrives shortly afterwards with his assistant, Mary, and someone called Todd who until this viewing I always thought was another assistant, but who I now notice introduces himself as a “fellow insomniac”.

The other thing I noticed for the first time here is Marrow’s earlier reference to Mary Lambetta’s “intuitions”, a remark that was apparently intended literally, since as soon as she steps into the house, Mary baulks, looking around apprehensively.

(As well she might: there is a forest of incredibly dangerous-looking, spiky, mace-like things suspended directly over her head. Yet another of the immensely practical household features.)

In the nature of things, this immediate reaction to the malevolent presence in the house marks Mary as The One Who Must Be Disposed Of, and this takes place without loss of time.

“For some reason I sense danger in this house…”

After dinner, consisting of too much wine and an upsized serving of clunky dialogue, the group gathers in front of a fireplace. Marrow distributes various psychological tests which his subjects are asked to complete over the coming days, and emphasises the isolation of their situation: nine miles from town, no TVs, and no phones – although he reassures them by showing that he does have a cell phone with him.

Place your bets now on the likelihood of that surviving the film.

Marrow then relates the history of Hill House, describing how on a fortune built on the back of his textile mills (and, more to the point, on the backs of his workers), Hugh Crain constructed the house in which he wanted more than anything to raise a family; how after suffering a series of stillbirths, his wife, Renee, died herself; how Crain became a recluse; and how afterwards, at night, the townspeople sometimes heard the sounds of children coming from the house…

Hmm. That would be the townspeople who lived nine miles away? And who never came near the place? In the night? In the dark?

Cue cheap jump scare. Then Mary abruptly remarks that there must be more to that story; that she can feel it, all around them… As she speaks, the house makes its move, and Mary is taken out by a skillfully-wielded clavichord wire, which slashes her face – and which has the desirable side-effect of pruning the cast back to its Name Star component, as it is (inevitably) Todd who drives Mary into town – and is never seen again. A big hand for Todd, ladies and gentlemen!

“…what he wanted most was a house filled with the laughter of children…”

Actually, I have belatedly conceived a great affection for Todd, who gets all of three lines of dialogue in this film, consisting of a total of nine words: “Greetings, fellow insomniac”, “Nembutal?” and, “Christ, I need a drink.”

On the other hand, there is definitely something “off” about this sequence. Mary smiling bravely as she presses a cloth to her cut face is one thing, but why would Marrow be grinning like an idiot? The suggestion seems to be that the accident was faked to freak out the others—but Mary’s injury is genuine, as Marrow later records in his notes. And even granting that Marrow’s a big enough bastard to take advantage of the moment, his overt glee is just…weird and disturbing.

And if this is somehow a set-up, what is Todd’s role in this? Was my first reading correct? – is he a “plant”, a researcher posing as another insomniac? But if he’s in on it, why would Marrow need to impress upon him and Mary that, “I want you both back as soon as possible?” And either way, why is it we never see or hear from Todd or Mary again? – particularly given that, at the last moment, Marrow gives Todd his keys and then re-padlocks the gates.

(Yup. Definitely negligent homicide.)

I can only conclude that, not for the first or last time in this film, something got lost or messed up in editing.

Todd! Todd! Come back, Todd!

Anyhoo— As they close the gates, Marrow tells Luke the rest of the Crain story, which is that the unfortunate Renee didn’t just die, but committed suicide. He then asks Luke “not to tell the women” (!), which he promises not to and then does at the first opportunity. It turns out that Marrow was counting on this, based on Luke’s personality profile, but still— Could he really come up with no better cover-story than, “Don’t frighten the wimminfolk”? Marrow also notes Nell’s “strongly sentimental” reaction to the Crain story, which I can’t say we’ve seen, before concluding smugly that it should only be a matter of time before these suggestible natures start dreaming up a haunting.

“A matter of time”, as in just over four minutes from now.

As Luke wanders the corridors sleeplessly, Nell tries to settle down for the night in spite of the hordes of leering wooden children (uhhuhhuhhuhhuh…) and those spiky wooden things, at which we are here given two more long, loving looks. Some time later, she is woken by a banging noise, and automatically responds by climbing out of bed with a sleepy call of, “Coming, Mother!” Only she isn’t at home any more. And that isn’t Mother banging on the wall…although something is…

A cry from the next room sends Nell running towards Theo, who is crouched on her bed staring around in fright as the pounding noise intensifies – and moves. A moment later, something tries to force its way through the bolted bedroom doors. A sudden intense chill envelopes the room, fogging the breath of the two women. Again, something throws itself against the doors – and then moves on.

Here’s a token screenshot of Catherine Zeta-Jones, whose character is so unnecessary, she appears nowhere else in my images.

In a sudden burst of courage, Nell scuttles forward, slamming home the bolt on the doors dividing her room from Theo’s, and just in time – an instant later, they, too, are under assault. Another knocking comes from behind – but it’s only Luke, reacting to the women’s cries. He and Marrow have heard and felt nothing…

A conference in the kitchen concludes with Luke demonstrating how noisy the water system is (which, of course, doesn’t explain why he and Marrow didn’t hear the banging noises), and then an unconvinced Nell and Theo retire again.

As Nell sleeps, a curtain billows, sweeping up to touch her bed…and we see the outline of a small child appear in it, sliding from the curtain to under the bedclothes, finally showing itself as an outline through the pillow next to Nell’s. Then it whispers her name…

At this, Nell turns over, and opens her eyes sleepily.

And blinks in mild confusion.

Which is, of course, how anyone would react to the sight of their bed co-occupied by a dead child – right?

Having whispered to her to, Find us, Eleanor, the manifestation disappears. Nell then climbs out of bed and shuts the window, before turning to gaze around her room with a dawning smile on her face – as if she were engaged in nothing more outré than a particularly successful game of hide-and-seek.

And if she wasn’t an insomniac before…

This—lack of reaction from Nell, though explicable, is incredibly damaging to the film as a whole. As I mentioned earlier, there are two supernatural forces at work within Hill House. The presiding spirit is that of Hugh Crain, a malevolent force; while opposing him (now that Nell is there) are the spirits of the children that Crain – for reasons never made entirely clear – murdered, and now holds earth-bound. Consequently, Nell, who is spiritually in tune with the children (for reasons that are made far too clear, sigh), is frightened by Crain’s manifestations, but knows instinctively that the children mean her no harm; on the contrary.

Okay—except that what this means in practice is that we fall into the habit of waiting for Nell to react or not react to any given phenomenon, to tell us whether it is “supposed” to be scary or not; a situation that puts far too much distance between viewer and film.

The next days, as they are completing some of their tests, Nell and Luke offer yet another of this film’s endlessly uncomfortable dialogue exchanges, in the course of which, Nell asserts that she likes the house and thinks it’s beautiful; this, only hours after something tried violently to force its way into her room, and she found a dead child in her bed. (Oh, right – that was the plumbing, wasn’t it? Sorry, carry on.)

Luke, a complete doofus yet somehow, sadly, the only one of the lab-rats to display any acuity, opines that Marrow is up to something, and there is a hidden reason that he brought them to this house.

“Nothing interesting ever happens to me…”

He departs, leaving Nell along in the cavernous room behind the Gates-Of-Hell doors – cosy! – which also contains the enormous fireplace guarded by stone lions. As Nell tries to complete one of Marrow’s tests, the curtain of chains hanging in the fireplace begins to stir. A strange wind gusts through the room, and then something looms up behind the curtain…

So, Nell— Scary, or not scary?

SCARY!! Nell gasps and runs, crying out for the others – though naturally they find nothing untoward, just more stone lions and an enormous ash-pit under the floor – and then a huge, lion-headed flue that creates a cheap scare by dropping into the scene in a way that just screams, “Look out for me later in the film!” The others assume that this is what Nell saw, though she vehemently denies it. And then Luke makes another discovery…

…and if there is one moment that defines this film – one moment that measures the distance between the two versions of The Haunting – one moment that, more than any other, pisses me off – it is this one: the revelation that, written on the wall at the top of the staircase in red paint – or something else – partly crossing the portrait of Hugh Crain, are the words WELCOME HOME ELEANOR.

The problem being that, in the original story, what was written there was:

HELP ELEANOR COME HOME ELEANOR

Just what the world needs, undead taggers.

Now, stop for just a moment and consider the number of ways that those words could be interpreted: three, at least – which was evidently two too many for Jan de Bont and David Self. I don’t think anything better illustrates the relentless dumbing down of the story for this film than this particularly bit of re-writing.

The scene of mutual accusation that follows is again out of place in this film. For one thing, since the little red footprints all over the floor indicate that the children are responsible, Nell should be delighted, not hurt and angry. A more appropriate response would be her crying out happily at this sign that the house wants her, while the others freak out at her reaction. However, what we get is Nell reproaching the others for their cruelty and withdrawing from the group.

Still more bewildering is that only moments later Nell is chuckling with Marrow over “welcome home” and expressing her glee at finally having a real adventure – “Like the women the bullfighters fall in love with” (!?).

This exchange takes place at the foot of a spiralling metal staircase – in this version transposed from the library to the conservatory – an amazingly stupid choice, conceptually, which I’m sure no-one gave a moment’s thought: in the library, it was for accessing books on high shelves. Here, it looks sort of interesting, but doesn’t really go anywhere.

Rather like this film.

And you need that in a conservatory—why, exactly?

The conservatory also contains a group statue (here re-worked into that of a woman caring for a group of small children), as well as a simply hideous fountain consisting of a large, contorted figure sprawled in a square pool and spewing water from its mouth, and which, like the lion-flue, will join in the action later on (although, as it turns out, a lot less effectually).

Night falls, and we get a series of spooky shots around the house: the exterior; a long corridor, seen – eek! – in Dutch angle; the portrait of Hugh Crain, now smudged and smeared after (as we were told) Dudley cleaned the paint off it. The door of Nell’s room opens by itself, and she wakes with a jerk when something touches her exposed foot. There is a trail of little red footprints on the floor, which she follows without hesitation. It ends at a bookcase, and after some fiddling Nell finds the catch of a secret door.

Behind it is a spiral staircase – another spiral staircase – which leads down to a room revealed as Hugh Crain’s study, where a dead child in a mirror helpfully points her towards his ledger – which is, naturally, a record of his nefarious deeds. All bad guys keep one, right?

By the way, if Hugh Crain was a recluse, why did he need to conceal his study, let alone his ledger?

The record turns out to be a list of the workers in Crain’s Concord textile mills – names, ages, occupations – deaths. Lots of deaths, all of them children, and not one adult – unlikely, one would think.

“And in there, that’s where we keep the dead children.”

Carrying her find upstairs, Nell tries to show it to Theo, but she is unreceptive (she had, for once, fallen asleep), so Nell takes it to her own room to discuss it with the dead children. The message she gets from them is an odd one: something starts to style her hair a particular way, which is finally a bit much even for Nell, who jumps up with a gasp, knocking a lamp as she does. Its light emphasises a portrait on the wall, that of a woman with her hair done just that way.

The next morning, Nell looks for Marrow, but finds instead his carelessly unsecured notes, including some unflattering remarks about her own emotional instability, and expressing his belief that she painted on the wall herself – but may not know it. She then tracks Theo and Luke to the conservatory. The latter believes that Marrow has pulled a “bait and switch” on them and is creating the phenomena himself to study their reactions (clever little lab-rat!); and that, at least, Nell now knows isn’t true. To this assertion, Luke demands to know why, if Nell believes the phenomena are real, would she stay one more second?

Nell: “’Cause home is where the heart is.”

And again I find myself in sympathy with Owen Wilson Luke, who gives an emphatic if silent, Whee-ooo.

Nell is prevented from saying any more when, upon glancing up, she sees a dead woman hanging from the spiral staircase – though the others see nothing. Confusingly, she then runs off looking for proof that she’s “not making this up”, and starts hunting through a stack of books, one of which – a photo-album – helpfully jumps off a shelf and opens itself up to reveal, first, posed shots of Hugh Crain with Renee, then of Crain with another woman – his hitherto unmentioned second wife, Carolyn – the woman of the portrait in Nell’s room.

She’s got Shannon Doherty eyes.

As Nell holds it, the pages of the album flick over, and a series of pictures of Carolyn seem to move and point to the fireplace. Evidently, however, Carolyn has a low opinion of Nell’s intelligence (or the audience’s), as she also whispers, “Nell, the fireplace…”

Obediently, Nell hurries to the fireplace and starts poking around in the ash-pit, where she finds beneath the ash some charred bones… And then – in an effect so telegraphed and cheesy, it always gets a delighted smile out of me – she finds most of a skeleton, which sits up and goes “BOOGA-BOOGA!” into the camera.

So—Hugh Crain, mass child-murderer. His way of “filling the house with children” (ew!), and keeping it that way permanently; even after death.

After a confusing sequence in which she runs along a corridor, tries and fails to open a particular door, and then runs back along the same corridor, an hysterical Nell gives a garbled version of her discoveries to the others, who are more concerned with her mental state than anything she has to say.

Marrow is suitably perturbed to discover that what they take to be her fantasy world is built on his “fake” version of Hill House’s history; perturbed enough to ’fess up. He sweeps aside Nell’s insistence that everything is real, trying to reassure her that they can all leave in the morning. But not until the morning. You know, when the Dudleys arrive to unlock the gates…

“Though of course, if you look at me carefully, you can tell I’m not a child’s skeleton…”

But before then, the battle between Hugh Crain and Nell Vance for the souls of the dead children will have begun in earnest—and The Haunting will have stopped being merely tiresome, and become profoundly silly. This transition is marked by the film ruining two more set-pieces from the original, first tossing away altogether the deeply creepy moment in which Nell realises – ulp! – it wasn’t Theo holding her hand, and then, in place of the “face in the wall”, which might just be a trick of the light, serving up a scene in which the entire room contorts itself into a huge, glowering face.

Not prepared to let all the stupidity belong to Hugh Crain, Nell shouts, “I will not let you hurt a child!” Uh, I think you’re too late, love; about 130 years too late.

She also tosses a heavy silver ornament at something lurking outside her window, which explodes. The shower of glass chases Nell from her room; and here we embark upon what feels like an endless series of shots of someone running along a corridor; occasionally leavened by someone running up or down a staircase.

The chase leads Nell across the water-filled passageway and into a mirror-filled room. To give the devil his due, we get an honestly unnerving bit here, as Nell keeps seeing reflections of someone who isn’t quite her; and she runs away into the funhouse-room, where she sees another not-her, this one pregnant. “Welcome home, Eleanor!” it smiles at her. Then it’s back to running down the corridors, until a dead child in a curtain stops her to tell her that, “Only the doors can hold him”; and then – after passing through her body – leads her into more corridor running.

The Amityville Horror did it better. (And so, for that matter, did The Last Warning.)

This chase ends in the conservatory, and the biggest of the re-worked set-pieces: Nell’s climb up the collapsing spiral staircase, from where a terrified Marrow must retrieve her.

(Liam Neeson sleepwalks through most of this film, but here he looks genuinely frightened – heights?)

As the flimsy metal structure gives way beneath him, Marrow hangs perilously suspended over the tiled floor – and his cell phone falls to the ground and smashes. Surprise! (Actually, it’s a bit late in the game for that, isn’t it?) Then, with Nell’s help, he manages to haul himself up onto the secure platform at the top.

Later, after Nell has been put to bed, Marrow chooses to top off the evening by pacing up and down the conservatory while dictating more experimental notes (!) on “the shared hysterical reaction”, commenting that, “The group is manifesting classic pathologies”. Oh, these hard-headed, sceptical scientists, hey? – stubborn to the last! Clearly, Marrow is in need of a lesson, and the house gives it to him – a surprisingly gentle lesson, all things considered – when the sprawling fountain reaches out, takes him by the shoulder, and drags him into the water – and then lets him go (!?).

While Theo is trying to get an explanation for Marrow’s sodden condition, the cameras are giving us yet another lingering shot of those spiky things over Nell’s bed. At this point, Nell looks up, gasping in shock as if she’s only just noticed that she’s been sleeping in a death-trap; and chooses this of all moments – the moment when the spiky things are detaching themselves from the ceiling in preparation for descent – to try and tell herself that, “It’s not real – nothing’s happening!”

This would be one of those “shared hysterical reactions” we’ve been hearing about.

What!?

Needless to say, she soon learns otherwise; although given that she is the one Hugh Crain needs to dispose of, we might wonder why the dreaded spiky things do nothing worse than pin her to her bed. (Oh, yeah – IITS©. Also, HDBE©.) And also needless to say, it is not until they have actually done so – and the room has largely destroyed herself around her – that Nell finally screams for help. This attracts the attention of the others (“It’s Nell!” exclaims Theo – well, duh), who after agreeing that Nell shouldn’t be left alone, left her alone.

As Nell lies helpless, a huge contorted face emerges from the ceiling, along with a forest of hands, although they do no harm (amusingly, on the visual evidence the hands can’t get at her through the spiky things!). The others then force their way in and break Nell free, carrying her out; the hands reappear, but again miss their targets; that’s some ineffectual malevolent force we got there.

The four run out of the house and up to the gates, which are very thoroughly chained and padlocked – another of Dr Marrow’s brilliant executive decisions – and are topped by spikes far more competent than the ones in the house.

As Luke pounds away at the chains with a shovel, we get the film’s big duh-duh-DAAAH moment, as Nell finally asks Marrow how he knew the house wanted her – why he called her to tell her about the study? To which Marrow replies, of course, that he didn’t…

“You know, it’s funny – I never really noticed these things before.”

Duh-duh-DAAH.

That’s right, folks. It wasn’t Marrow on the phone that day, it was a bunch of dead children.

Dead children who’d seen Marrow’s ad in the Boston Globe.

Giving up on the shovel, Luke appropriates Nell’s little car and drives it at the gates, and—nada. Except that he succeeds in dislodging a piece of wrought-iron decoration covered in spikes (again with the spikes, Jan? really?), which plunges down into the roof of the vehicle and nearly into Luke. This has the odd side-effect of causing a fuel-leak (?), so there is a desperate race to smash the back window and drag Luke to safety; although as it happens the car defies all known cinematic laws by not going up in a gigantic fireball; probably because someone realised belatedly that this would, in all likelihood, blow the gates open.

While this is going on, the children start calling for Nell, so she heads back into the house. The others go back in too, to look for her, a task entailing much running back and forth along corridors, and up and down staircases, and finally find her – the final botched re-worked moment – behind a door she earlier tried and failed to force open, but which now sits open to reveal the nursery…which is simultaneously a reproduction of “Mother’s” bedroom in Boston, right down to the cane across the bed and the sententious sampler on the wall.

“Call 555-DEDKIDZ.”

I find it infuriating that in a film with so much wasted time, so much unnecessary back-and-forth, instead of following Nell as she makes more discoveries, we are now just given the rest of the back-story in an awkward info-dump. Not revealing where she got her knowledge from, Nell announces to the others that the second Mrs Crain was her great-great-grandmother, and that of all Hugh Crain’s victims, she alone – somehow – escaped Hill House. (Presumably taking her baby with her, though the actual dialogue seems to suggest otherwise.) Which makes Hill House Nell’s true home – somehow. And the dead children Nell’s family – somehow. And if she’s there, Hugh Crain can’t hurt them any more. Somehow.

Hey, I just report this stuff. I suppose…that Crain must have lost it when Carolyn took his one and only child away, and decided that from then on no child would ever be allowed to leave Hill House. And yes, I am thinking about this more than David Self did.

Hugh Crain, having waited politely for Nell to finish her story, now springs into action again. Nell insists that she won’t go, but does agree to help the others leave, which entails more running back and forth and up and down, as well as much slamming of doors – including the key ones. “He’s not gunna let you go,” concludes Nell sadly.

As she looks on in resignation, the others try smashing their way out the windows, to no avail. Marrow gets a piece of glass in his hand, and while the women are taking care of his injury, Luke loses it, jumping up on a sideboard and slashing wildly at yet another glowering portrait of Hugh Crain (collect the whole series!).

Shoulda crashed the gate doing ninety-nine…

This Crain takes personally: Luke is suddenly scooped up on a rug and dragged right across the room, before being flung into the fireplace. He staggers to his feet, somewhat bruised but otherwise unharmed; and then, even as Nell shrieks at him to, Get out of there—

Hey, remember that lion-headed flue??

Ah, PG-rated decapitations…! God love ’em.

And as with the toasting of Elliot West in Amityville 3-D, Luke’s sickly funny death is the cue for all manner of hitherto unseen phenomena to burst simultaneously into life.

(Seriously— The 3D aside, the two films are by this point nearly indistinguishable. Except that there’s no flying stuffed swordfish in The Haunting, which of course makes it the inferior work.)

The ash-pit explodes, showering bones and other debris around and driving the others out of the room. Nell, suddenly au fait with all manner of Hugh Crain-related factoids, announces that, “He used to play hide-and-seek with them. That’s why he built the house. You have to hide.” (!?)

“Blecch! Too fatty!”

While they’re still debating the point, old Hugh’s portrait lurches off the wall and, though it falls short of crushing anyone, injures Theo’s arm with its rim of, sigh, spikes. We note with interest that Theo loses more blood in this incident than Luke just did.

As the three run away, a stone griffin on the stairs comes to life, and we are subjected to the wholly unedifying spectacle of Nell smacking it around the head with a wooden board and shouting abuse at it.

(Note to film-makers: supernatural manifestations that can be beaten up are NOT SCARY.)

And then it’s time for even more running up and down corridors.

Nell has fallen behind the others and gets separated from them, finding herself in a cul-de-sac bearing yet another portrait of G-G-G-Carolyn – or rather, yet another reproduction of the same portrait (?) – and realising, at long last, that in it Carolyn is wearing the very pendant now hanging around her own neck, which she found amongst her mother’s effects.

Nell seems stunned by this, though I can’t think of any reason why at this stage she should be. My suspicion is, this scene was meant to come before the nursery scene, but got misplaced in editing.

“…the sounds of children SCREAMING!!”

In any event, this final incident determines Nell upon a course of action. She strides back out, past the stone griffin (which sits very still and meek), and takes up a position at the top of the staircase, from where she shouts defiantly, “Hugh Crain!”

He appears briefly, in yet another billowing curtain, but Nell doesn’t see him. Still shouting his name, she walks downstairs and picks her way through the children’s bones now strewn across the floor. She is obviously at a loss what to do next, so some of the dead children helpfully prompt her to, “Bring him to the doors” – meaning, of course, The Gates Of Hell.

Suddenly, the fallen portrait picks itself up and re-hangs itself, and then a flowing black version of Hugh emerges from it, swooping down the stairs towards Nell, who gamely holds her ground. At this most inauspicious moment, Marrow and Theo find their way back, and gawp in disbelief at the writhing figure towering over them. It moves towards them, but Nell steps in between—

Pardon a digression.

1999 was a banner year for bad movies. (Not coincidentally, it was also one of the last years I went regularly to the cinema.) In saying this, we must further acknowledge that it was, perhaps above all else, a banner year for bad movie dialogue. This was, after all, the year that produced both, “I’m a scientist – that’s what we do!” and “Yoo-err fuckin’ kwar-boy compare to me! A KWAR-BOY!!”

“Jeez, lady, don’t blame me! Take it up with your agent!”

However, fond as I am of both of those – particularly, of course, the former – they pale beside the speech that David Self here puts into the mouth of the unfortunate Lili Taylor, when Nell decides that the best way to deal with ol’ Hugh is to talk him to death.

Although I suggested at the outset that The Haunting’s main sin is disrespect of its source, I may have been committing an injustice; it may, instead, simply be a case of this film’s makers not really understanding the story. Either way, the result is a bad film, but for the most part not a great bad film. A pointless bad film, you could say; or a tiresome bad film; or just a forgettable bad film; at least – it is until we get to this moment, which all on its own lifts – or drops – The Haunting into a whole different realm.

And I quote:

“I’m not afraid of you! I’m not afraid of you any more! The children need me, and I’m going to set them free! Even in death, you still wouldn’t let them go! I’m gonna stop you now…!” [Crain tosses Marrow and Theo across the room] “It’s not about them! It’s about family! It was always about family! It’s about Carolyn – and the children from the mills! If you could hear their voices— It’s family! Well, I’m family, Grandpa, and I’ve come home! Now it’s just you and me, Hugh Crain! Purgatory’s over – you go to hell!”

So if I’m understanding her correctly, it has something to do with family.

A powerful argument for birth control.

Ah, dear, dear, dear… You know, I remember laughing at that the first time I ever saw this film – and then giggling over it again afterwards, every time I thought about it. And indeed, those of you who have been around long enough might even remember a time when I used to try and shoehorn the line, “IT’S ABOUT FAMILY! IT WAS ALWAYS ABOUT FAMILY!” into every conversation that I could.

Anyway— Nell’s speech causes the spirit of Hugh Crain to roar in agony (we can only empathise), and demons to emerge from the metal doors, where previously they were holding onto the spirits of the dead children and preventing their ascent to heaven. The demons swoop upon Hugh Crain and seize him, but as they carry him toward the doors, he in turn seizes Nell, who is violently slammed against the metalwork.

The struggling Crain is dragged down into the frieze, while two demons take hold of Nell and gently lower her (in a tasteful crucifixion pose) to the ground. She recovers just long enough to see the freeing of the children – all of whom thank her politely on their way out and up – and the final captivity of her “Grandpa”, before dying for no readily apparent reason. Her last breath can barely have left her body when her own spirit pulls itself free and sets off after the children. Much swooping and smiling ensues.

Despite having just witnessed Nell’s soul cavorting near the ceiling, Marrow crawls across and checks her pulse; a sceptic to the bitter end. He and Theo then ride out whatever’s left of the night, and cometh the dawn, cometh the Dudleys. Mrs Dudley curls a sardonic lip, while her husband peers through the bars of the gate at the two weary and battered survivors, standing behind the smashed remains of Nell’s car. “Find out what you wanted to know?” he inquires.

For someone who was so happy to be home, she sure looks glad she’s leaving.

And as the credits roll, I find myself wondering what on earth they’re going to tell the police…?

Footnote: Many a time I have laughed at this film, but never so hard as this morning, when I was taking my screenshots. I was going over the final confrontation in fits and starts of fast-forward, looking for particular frames – with the result that Nell’s climactic speech was rendered as: “…family!…family!…family!…purgatory!…”

Want a second opinion of The Haunting? Visit Braineater and 1000 Misspent Hours – And Counting.

“Hey, you! Yeah, you, Jan de Bont! Get over here…”

Isn’t the last line by Mr. Dudley, spoken in disgust, “City folks!”? I always thought that was strange. Do country folks not get haunted? Or are they just smart enough to stay away from the house, in the night, in the dark?

I didn’t think the first movie in 1963 did the book justice (but much much much more than this one). The idea of a house that was designed (for starters) so that all the doors will swing shut automatically, and everything is just a little off-kilter, is very hard to put into a movie script. And the fact that everything that happened could have been supernatural, or just the figments of Nell’s disturbed mind, is much scarier than most of what Hollywood comes up with.

I read this book for the first time when I was substitute teaching, right out of college, during a free period. If any student had come up behind me, I think I would have jumped through the roof – but nothing really was happening. You just felt that around the next corner (or on the next page) would be something horrifying.

LikeLike

Hi, Dawn! It’s Mrs Dudley who says it – I don’t have the subtitled copy any more so I can’t be sure, but to my ears it sounds like she’s saying, “Silly people.” Mr Dudley gets the last word, though. 🙂

You’re a tough audience! – given that The Haunting Of Hill House is essentially unfilmable I think they did a pretty remarkable job capturing so much.

LikeLike

Ah, those cinematic ethics committees. So much more accommodating than the real-life ones!

Somebody really ought to set/shoot a film in the Erich Lindemann Mental Health Center in Boston, for a genuinely scary location. Do some image searches. It was designed by an architect who had a romantic view of mental illness, so there are lots of inverted stairways, corridors that lead nowhere, looming faces, strange perspecives, and so on. Three separate patients were apparently inspired to self-immolate in the chapel. The whole place is used as office space now…

Yes, obviously the townspeople heard the sound of children from nine miles away. Noisy brats. And really, which of us can say he hasn’t murdered the occasional child and buried them in unmarked graves? And obviously Hugh Crain simply didn’t employ any adults in his mills…

I strongly suspect this film was edited out of order. There should presumably be a gradual transition from “Nell is scared and confused” to “Nell is prepared to help the child-ghosts get free”. Instead, Nell’s sudden knowledge reminds me of the way that in Christian™-brand films someone who’s just converted instantly learns all the ways Christians speak to each other.

The spiral staircase in the conservatory is for getting at the windows to clean them, of course. The stained-glass blood vessels in the eyes are a nice touch, though.

So when the house was made ready for this experiment, the fence round the grounds was upgraded to unclimbable-by-desperate-people, but nobody emptied the ash out of the fireplaces. Ooooo-kay.

Ah yes, Jan “I was born in Eindhoven, what sort of angle do you expect me to use” de Bont.

What to tell the police? “(dead person) and (dead person) went mad and started smashing up the place!”

de Bont has only directed one film since this, and it was back to his more usual action style. And by all accounts it was pretty rotten; Twister and Speed at least work as basic “run around and get excited” films. David Self has had four other screenplays produced, none of which I’ve seen. And I don’t think I’ve seen Lili Taylor in anything else… oh, wait, she was the police captain in the underrated (but still not particularly good) Almost Human a couple of years ago.

LikeLike

So much more accommodating than the real-life ones!

You’re not wrong. Buncha killjoys…

Oh, no, Hugh Crain employed adults, all right, and apparently his mills had a wonderful health plan because they all lived to a ripe old age.

And yes, absolutely this film was mucked up in editing, the whole tempo of Nell’s experiences is wrong.

I haven’t seen it yet but almost every review of The Conjuring I’ve read has said something like, “How nice to see poor Lili Taylor in a good horror film!” 🙂

(ETA: Of course, given the Amityville connection, I should have seen it…)

LikeLike

I have odd moral qualms about The Conjuring – I’ve spoken with real-life victims of Ed and Lorraine Warren, and I can’t bring myself to watch a film that portrays them as anything other than vicious con-artists.

LikeLike

Great review. I had the misfortune of seeing this one in the theater when it came out and I still wish I had seen Deep Blue Sea instead. It’s an equally bad film but so much more fun to sit through.

LikeLike

Hi, Ed – thanks!

Boy, 1999… No wonder people thought it was The End Of Days (so to speak).

LikeLike

I have odd moral qualms about The Conjuring

I don’t think that’s odd at all. I’m sure the film-makers didn’t think much further than that these people were the forerunners of today’s Ghost Hunters / Paranormal Witnesses etc., but as we know the story’s not quite that simple, or harmless.

On the other hand, given that the entire Amityville franchise is built upon a philosophy of “We prefer this version of the story”, I’m not sure I’m in a position to criticise.

LikeLike

Pingback: Association of ideas « The B-Masters Cabal

I have a soft spot for this one, and I don’t really know why. Is it the utter bad wrongness of the awful CGI? The valiant struggles of actors trying to play against the scene-stealing set? Everything about this movie just goes totally wrong, but I’ll watch it (or the slightly better, if equally misguided, remake of “The House on Haunted Hill”) whenever I trip over it on cable. I remember Lili Taylor as a vaunted indie actress in the 90s and I don’t know if she ever entirely recovered from this one.

LikeLike

Hi, Maura – thanks for visiting! Oh, I do too, if we’re honest: I abuse it and abuse it, but look how many times I’ve watched it… 🙂

It’s sad when one film stymies a career but it does seem that’s what The Haunting did to Lili Taylor; the fact that people tend to refer to her as poor Lili Taylor speaks for itself. It’s good to see things may be picking up for her again, albeit rather belatedly.

LikeLike

IMDB makes it seem like Poor Lili Taylor’s been working steadily enough since 1999, but not in anything most of us would have seen. It seems to be picking up for her in the past few years, though, although IMDB says her latest upcoming movie role is in some Texas Chainsaw Massacre movie, so perhaps The Conjuring hasn’t been that great for her. Who knows, maybe she’s one of those actors who just prefers the stage. This movie seems to have been a blip on the resume for Liam Neeson, Catherine Zeta-Jones, and Owen Wilson.

I’m a long time reader and recommender, first time commenter…. well, second time now!

LikeLike

I thank you for the readings, the recommendations and the comments! 🙂

IMDB says her latest upcoming movie role is in some Texas Chainsaw Massacre movie

Okay, that’s weird. Maybe she wants The Haunting not to be the worst film on her resume any more??

LikeLike

Ahh, the films of 1999. My friends and I saw at least one movie a week that year, a mistake which I for one have not repeated.

I was mostly unfamiliar with the sources for this one back in ’99, but it was shocking how awful and not-scary this huge-budget, big-name stars “horror” movie was. As an aside, Theo’s character – I myself am openly Bi/Pansexual, and the way Hollywood treats characters of alternate sexuality really helps me relate to Lyz’s exasperation with Hollywood scientists.

Loving the updated reviews, Lyz. 🙂 This was always amusing and informative to read, now I can add Laugh-Out-Loud Funny. XD “Shannon Doherty Eyes”. And, OMG, are you a fan of “Whose Line is it Anyway”? Yay!

LikeLike

Hi – thanks, for visiting, and for following – much appreciated!

Oh, wasn’t 1999 just fabulous!? I really must sit down and start giving the rest of that annus mirabilis a makeover! 😀

Goodness yes, that must be an infuriating situation for you – my sympathies!

I haven’t seen so much of the more recent WLIIA, but I used to watch it a lot with my father, who was a big fan. 🙂

LikeLike

Hi Lyz! 🙂

I am really looking forwards to your further updates of the dreck of ’99, especially “Mission to Mars”. XD Isn’t it sad that “The Phantom Menace” wasn’t even the worst big-budget SF movie of that year? I’m really excited with you migrating to Blog format, I’ve enjoyed so many of your reviews, and now I can tell you and express some of my reactions and opinions.

About sexuality: Thank you. I think it would help if the decision makers in Hollywood met even a few actual LGBT folks. If I see *one more* movie or TV show with the Quirky Queer BFF…. XD

WLIIA is a real joy for me, I watch it with my Mom a lot. It doesn’t matter if it’s the original, the Drew Carey, or the new re-launch, I just love the humor and inventiveness. Colin Mochrie especially regularly reduces me to tears of laughter.

LikeLike

Oh, lord, Mission To Mars—I’d almost forgotten that. I must confess, my mind went immediately to Deep Blue Sea and Bats…and then maybe End Of Days, so I can watch Miriam Margolyes beating up Ahnold again. 😀

LikeLiked by 2 people

Looking through Wikipedia’s “1999 in film” page… some people liked The Sixth Sense, but if you spotted what was going on on the first pass (as I did), it really had very little to offer. Quite put me off M. Night (before it was cool). And Blair Witch. Even if I’d enjoyed it I’d have trouble forgiving it for starting the found footage genre. Oh, wow. Bats! With the great Lou Diamond Phillips! I’d forgotten what a goldmine this year was.

LikeLike

I can’t say I have a problem with either of those two: I think they both attract a lot of retroactive criticism because of what they unleashed, rather than because of their own failures. I still find them both effective in their own right.

So, yeah—1999: The Haunting, Bats, Deep Blue Sea, End Of Days, Mission To Mars, Stigmata, Lake Placid…

Wow.

Looked at from that perspective, we can see that Anaconda was just a little ahead of its time; a Harbinger Of Doom, as it were… 🙂

LikeLike

1999 was a banner year for cinematic Turkeys, wasn’t it? XD I’ve always enjoyed your skewering of ‘Deep Blue Sea’ especially. I love shark movies, even stupid ones.

LikeLike

Me, too. Obviously. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

I at least appreciate the inclusion of a picture of 29-year-old CZJ, regardless of pretext.

LikeLike

Happy to oblige in that respect, but really she was wasted here.

(Wasted, not wasted; though you wouldn’t blame her.)

LikeLike