“The quake is moving eastward. Gulf Of Mexico flooding entire area. Chicago is doomed. Messages indicate Mississippi Basin sinking…”

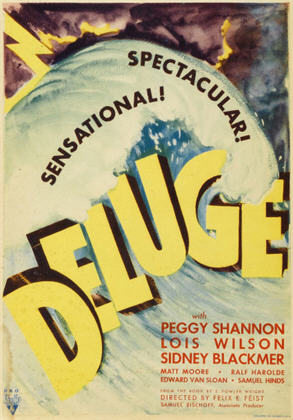

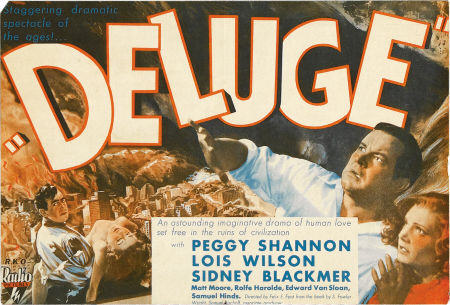

Director: Felix E. Feist

Starring: Peggy Shannon, Sidney Blackmer, Lois Wilson, Fred Kohler, Matt Moore, Lane Chandler, Samuel S. Hinds, Edward Van Sloan, Ralf Harolde

Screenplay: Warren Duff and John F. Goodrich, based upon the novel by Sydney Fowler Wright

Synopsis: Around the world, scientists hold grave fears over the effects of bizarre and inexplicable weather patterns. Warnings of imminent violent storms are broadcast; all aeroplanes are grounded, and all ships ordered to return to port. In New York, Claire Arlington (Peggy Shannon) has her attempt at a long-distance swimming record summarily cancelled by city officials. Then the impossible happens: an unanticipated eclipse. At the Astronomical Society, Professor Carlysle (Edward Van Sloan) receives grim news from Italy, which has been shaken by earthquakes for four consecutive days. Similar reports come from England. Panic sweeps the globe, as people begin to fear that this may in fact be the end of the world. Soon, the catastrophe strikes the United States, with the entire west coast destroyed by earthquakes of unprecedented magnitude. News from the rest of the world is cut off as communications systems fail. The quakes move eastward; the Gulf of Mexico is overwhelmed by floods. Regional broadcasting warns people that disaster will soon strike locally. In an isolated house some forty miles from New York, Martin Webster (Sidney Blackmer) listens grimly to the radio as his wife, Helen (Lois Wilson), prepares their two young children for bed. A violent storm breaks, and the chimney of their house crumbles under its impact. Martin hurries to Helen, declaring that they will be safer sheltering by the rock walls of a nearby quarry than in the house. Martin carries the children from the house, as Helen gathers clothes for them. Suddenly, a tree crashes through the house. Having left the children in safety, Martin hurries back, finding Helen under a pile of debris, trapped but not seriously injured. Pulling her free, Martin carries her to the children. As the next day dawns, with a brief lull in the storm, Martin returns to the house to collect more food and clothing. Meanwhile, a final broadcast warns that the earthquakes are approaching the east coast, advising evacuation of the cities. Barely has the message been spoken than the quakes begin. New York crumbles, its buildings reduced to shattered ruins and innumerable lives lost. Then a massive tidal wave hits, and the few remaining buildings are swept away by the inrushing waters… At long last, the storm recedes and the weather clears, revealing a very different world: a world covered largely by the risen waters, with only isolated pockets of land remaining. On one of these, Martin Webster struggles to consciousness, and looks around to find himself utterly alone… On another island, the brutish Jephson (Fred Kohler) begrudgingly allows the cowardly Norwood (Ralf Harolde) to share his small hut. Ordering Norwood to get a fire started, Jephson goes outside to get water…only to return with an unconscious, barely-clad woman in his arms. He carries her to the hut’s only bedroom, where the two men gaze at her hungrily… Claire Arlington wakes in time to overhear a violent argument between Jephson and Norwood, the former asserting his right to her, and realises that she has survived the world’s catastrophe only to be faced with a new and imminent danger…

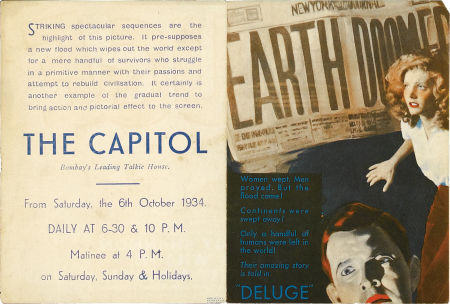

Comments: Deluge is a film with a strange history. Produced independently by a small outfit called Admiral Productions, Incorporated; sold to RKO (who were looking for a suitable cash-in follow-up to King Kong); and released during August of 1933 to a mixed but generally positive critical response, the film went through a successful cinema run and then, apparently, vanished from the face of the planet. The only evidence of the film’s existence lay in the vivid memories of those who had witnessed the cinematic destruction of New York during Deluge’s first and only run, and in the occasional reappearance of that spectacular special effects footage, which somehow ended up in the possession of Republic Pictures, and was integrated by that notoriously penny-pinching studio into a number of films and serials, most famously the climactic episode of 1949’s King Of The Rocket Men.

Otherwise, Deluge seemed to have joined the tragic ranks of “the lost film”, until the serendipitous discovery of what is to all evidence the sole surviving print of it by the late Forest Ackerman, during a visit to a cinema archive in Rome during 1981 – which explains why all existing copies of the film are dubbed in Italian. English subtitles were subsequently added to the dialogue, but such internal signifiers as signs and newspaper headlines – and, for that matter, the film’s titles – remain untranslated; an arrangement that adds a distinctly surreal edge to a contemporary viewing of what is indisputably the progenitor of all modern-day disaster movies.

Deluge is a disaster movie rather than a science fiction film chiefly because it offers no explanation of any kind for its catastrophes: they just happen. We might be tempted to call these events an act of God, but the film takes pains to let us know that they are anything but. Deluge opens with a quote from Genesis, a reminder of the covenant between God and Noah: Neither shall all flesh be cut off any more by the waters of the flood; neither shall there any more be a flood to destroy the Earth. This is meant as reassurance: this film is simply a fantasy, it couldn’t really happen.

Deluge is a disaster movie also because of the way it shifts the focus of its source material. Sydney Fowler Wright was more or less a contemporary of H.G. Wells, and like him wrote tales that might be called “scientific romances”; but there the comparison ends: the philosophies of the two were violently opposed.

Fowler, like many in the post-WWI era, was profoundly suspicious of the industrial complex, which he regarded as responsible for much of that conflict; but it did not stop there: he was also deeply hostile to the whole concept of “civilisation”, upon which he blamed what he regarded as the degeneration of the human race. He was similarly against “progress”, and against “science”, and against “the law”, and against—well, evidently there was very little in existence during the 1920s that Fowler was not against, although his two main specific bugbears seem to have been the motor car and the idea of birth control. (And as a corollary to the latter, he believed that only civilised women suffered pain during childbirth, a consequence of their “degenerate” physical condition.)

A significant proportion of Fowler’s writing concerns the sweeping away, by one means or another, of this hated modern world, and the subsequent struggle and triumph of a chosen few in a strange but (in his opinion) superior realm. Thus, in the novel upon which Deluge was based, the global catastrophe that re-writes the face of the planet and eliminates all but a handful of human beings occupies only the first couple of pages; for Fowler, the violent earthquakes and the rising of the seas are merely a means to an end.

Not so for the makers of the film Deluge, however, who were determined to give their audience something it had never seen before. Cinema-goers had certainly witnessed large-scale destruction before, primarily during the Thou Shalt Not final reels of various Biblical epics of the silent era; but this would be something else, something new: the destruction of a contemporary city.

Sydney Fowler Wright, an Englishman, set his novel in England, and has a portion of the Midlands – not the most visually distinctive region – remaining above water after the disaster strikes. The producers of Deluge, in contrast, shifted the action not just to America, but to its most recognisable city; and in doing so, they set a film-making precedent that, to this very day, is followed with an almost religious devotion. Even now, a full seventy-six years later, when many other cities might put in a claim for equal recognition on the strength of their landmarks, poor old New York barely gets a minute’s peace.

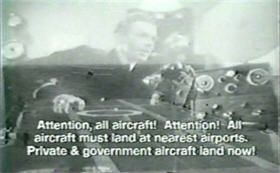

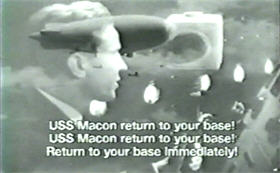

The section of Deluge that precedes the devastation of New York offers the modern viewer a fascinating glimpse into the past. We start out visiting with worried scientists, looking on with growing trepidation as the barometers plunge to unprecedented depths, and then with panicky astronomers, gazing up at a solar eclipse that they did not predict. The recall of ships and planes is achieved via the superimposition of a radio operator over stock footage, and in this way we are shown not only a variety of standard air and sea transports, but also two different kinds of aircraft carrier. The first is the more conventional, sea-faring variety, on which the fighter planes of the day, biplanes with propellers, are shown landing. (I think these are the aircraft designated “Sparrowhawk”, but this really isn’t my area of expertise.) The second is USS Macon, an intriguing artefact of the history of air travel – and air conflict.

The Macon was a rigid airship, or dirigible (or zeppelin, depending upon where and by whom it was built), a craft capable of launching and retrieving five fighter planes. It had a two year service history, being employed in a variety of naval exercises and research projects from its commissioning in June of 1933 – when Deluge was in production – until February of 1935, when a violent storm induced a structural failure that caused the vessel to crash off the coast of California. The sunken remains of the aircraft were not located until 1991. Deluge makes use of newsreel footage of the ship, showing it in flight surrounded by its tiny fleet of fighters, and on the ground, being returned to its massive hangar at the New Jersey base where it was built, and from where it made its first test flights. At the time of Deluge’s production, the Macon had not yet been placed in active service; this footage is a marvelous little time capsule.

The early part of Deluge also introduces us, briefly, to our three central characters. We are given are a rather provocative glimpse of Claire Arlington, lying under a towel and being given a grease rub-down by her masseuse prior to the proposed long-distance swim that is one of the more minor casualties of the imminent disaster. (In the script, Claire was to attempt to swim around Manhattan Island, but this detail is no longer present in the film itself.)

We then spend rather more time with Martin Webster, his devoted wife, Helen, and their two young children. The Websters occupy an isolated house some forty miles from New York City (my regional geography isn’t strong enough for me to hazard a specific guess as to their intended location). As Helen listens to the children’s prayers – encouraging them in “If I should die before I wake—” is, I suppose, a practical move – Martin paces by the radio, learning that the worldwide disaster is now upon their own doorstep.

As the house begins to crumble, a victim of the growing storm, Martin decides to move his family to a nearby abandoned quarry, where they can shelter against a rock wall. Helen is injured when part of the house collapses, but Martin manages to free her, carrying her to the quarry and leaving her with the children before returning to the house in search of food supplies and clothing. It is at this point that the storm reaches its climax…

Perhaps the most remarkable thing about Deluge is that it was not the work of a highly-resourced major studio, but rather emanated from one of the many tiny independent outfits that at the time operated upon the fringes of Hollywood. Burt Kelly, Sam Bischoff and William Saal spent the early thirties primarily churning out budget westerns via their company, KBS Productions; but when their distribution outlet, Sono Art-World Wide Pictures, began to founder financially during late 1932, the KBS executives cut their ties, dissolved their company, and reformed into a new entity, Admiral Productions, Incorporated. Admiral only released three films – one more western, a sub-Runyan comic gangster film, and Deluge – but it served its purpose: such was the impact of Deluge that all three of its producers were swiftly head-hunted by the majors. Given that the spectacular effects work in their signature film had gone wildly over budget, putting the small company into significant debt, the three men were only too glad of an escape; and only a year after it was formed, Admiral Productions ceased to be.

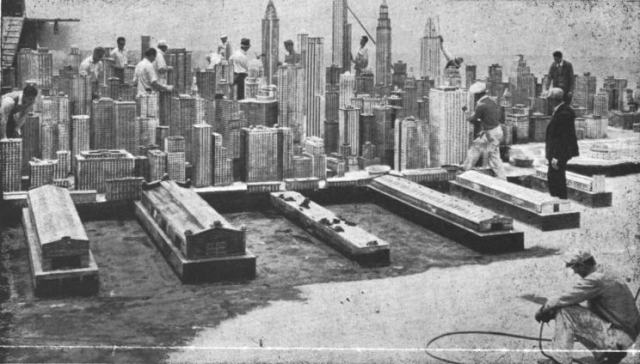

The special effects in Deluge were the work of three men: cinematographer Billy Williams (who, many years later, was involved in shooting the opening credits of Vertigo); matte artist Russell Lawson; and model builder Ned Mann, who had also worked on what was, prior to Deluge, Hollywood’s nearest attempt at a disaster movie, Darryl F. Zanuck’s production of Noah’s Ark. Like his producers, Mann would find himself in hot demand thanks to his contribution to this film, and was tapped by Alexander Korda to head up the special effects team for Things To Come. To facilitate the destruction of New York, Mann built a scale model of the entire city and harbour, complete with breakaway buildings, which covered a complete soundstage, one specially enclosed in order to allow the flooding of the set.

The conceit of Deluge is that this unexplained catastrophe commences in Europe and then travels eastward around the world, devastating region after region, country after country, with earthquakes of unprecedented magnitude being followed by hurricane-force winds and tidal waves. The lead-up to the climax of devastation is achieved largely through the use of stock footage which, while obvious, is still effective, particularly the scenes of a real hurricane that are used to visualise the destruction of the Gulf of Mexico.

As religious leaders address their flocks (exhorting repentance or counselling faith, according to preference), as Martin Webster listens in near despair to his radio, as the emergency broadcasters send a belated and futile message to the people of New York, urging them to evacuate, the earthquake hits. Buildings shatter and fall, crushing the screaming and panicked residents who stream into the streets. Skyscrapers, apartment blocks and prisons alike crumble into ruin. A massive tidal wave pours in, swallowing the harbour – and then the city. The earth itself splits apart, and a maelstrom of water and debris pours into its depths. The Empire State Building disintegrates. The Statue of Liberty alone stands defiant in the face of catastrophe, its torch held stubbornly aloft above the engulfing waters…

Of course, at this blasé distance it is easy enough to recognise the various flaws in the implementation of this sequence: chiefly the unconvincing superimposition of footage, but also some obvious model work, and that perpetual disaster movie bugbear, a lack of scale and weight in the watery destruction scenes; but ultimately, these shortcomings matter very little. The sheer ambition of this four-minute sequence, its relentlessness and intensity, make it very easy indeed to overlook any technical imperfections. No wonder that its creators were so quickly snapped up by rival organisations. No wonder that so many of those people who saw this film during its single run in 1933 were able to recall this sequence with clarity even decades afterwards.

One of the most critical aspects in the making of a disaster movie is the question of structure. By definition a disaster movie is primarily about spectacle: how does it strike? – and perhaps more importantly, when? – at the beginning? – at the end? – all the way through? Is the disaster the catalyst for the action, or its climax? Is the spectacle consistent, or will we be obliged to spend an indeterminate period with characters who may or may not hold our interest to the same degree?

Many disaster movies – more in honesty than cynicism – recognise the sadistic streak in their audience, and pander to it by offering up A, or B, or C – or Z – list actors and subjecting them to a variety of gruesome fates; others stint on the disaster scenes and then – apparently in all seriousness – imagine that the audience will be compensated for this lack by, most frequently, the reconciliation of an estranged couple or family.

Deluge itself must be exempt from most of this analysis, of course, purely by virtue of being the first, and thus having no template or example other than its source novel. On the other hand, there is a contemporary disaster film that, structurally, resembles Deluge to a remarkable and occasionally amusing degree – namely, The Day After Tomorrow, which like it posits a worldwide catastrophe of unimaginable magnitude, crams all of its disaster footage into its first third, and inflicts its tortures predominantly upon New York.

(I’m ambivalent upon the question of whether this resemblance is intentional or not. Some scenes in The Day After Tomorrow, particularly the use of the Statue of Liberty, look like a direct copy. On the other hand, I suppose using the Statue like that is a fairly obvious choice; and quite frankly, Roland Emmerich doesn’t strike me as the kind to bother researching his roots, least of all with respect to an obscurity like Deluge.)

As to which of these two films is “better”, that is very much a matter of personal taste; although to my mind Deluge does have two distinct advantages over its mega-budgeted descendent. Firstly, it’s a merciful full hour shorter; and secondly, although it commits the same disaster movie sin of serving up no more disaster in its latter two-thirds, the character scenes that take the place of the spectacle stay reasonably close to the tale that they were based upon, and therefore carry with them much of Sydney Fowler Wright’s peculiar personal philosophy; a philosophy that, whatever else one might say about it, certainly has the quality of arresting the attention.

When the quakes subside and the waters recede, Martin Webster staggers to his feet to confront a world wholly altered, a desolate landscape of inland seas, of shoals and islands. In time he locates an abandoned hut, near a newly excavated railway tunnel; and, having secured shelter, begins the task of gathering supplies…

Elsewhere, in another lonely shack, two men are making a staggering discovery: one of them, going out to fetch drinking water, finds an unconscious woman almost on his doorstep. Claire Arlington later wakes to find herself the object of an argument over which of the two men “owns” her, with the larger of them, the brutish Jephson, laying claim to her as a matter of course, insisting that he owns her as he owns everything else in the hut, and telling Norwood bluntly that if he doesn’t like it he can get out and find his own shelter.

Nevertheless, it is the seemingly more timid Norwood who offers the first threat. Taking advantage of Jephson’s temporary absence, Norwood attacks Claire, who defends herself stoutly with the help of a handy frying pan. Jephson, hearing sounds of a struggle, returns, glaring in fury as Norwood releases Claire and cringes back. Jephson rushes in, seizing Norwood by the throat.

Claire takes advantage of the moment and flees the hut, stripping off her clothing and plunging once more into the surrounding waters, swimming for her life and safety. Jephson stares after her in a rage, then gathers supplies, food and a rifle, and begins preparing his boat…

Some time later, Martin emerges from his own shelter to find a figure lying motionless on the shore. He carries the exhausted Claire into his cottage, and puts her to bed. Meanwhile, Jephson, too, makes his way to Martin’s island, although he does not immediately see the cottage. Worried, Martin shadows him as he searches, and thus both men in turn make a grim find: the dead body of a young woman, tossed carelessly aside after being raped and murdered.

By the time Martin catches up with Jephson, the intruder has made contact with more strangers, a rough band led by a man called Bellamy. Martin overhears news of a settlement of some two hundred survivors, situated twenty miles to the south, who ran the violent band out of town. Then, to Martin’s horror, Jephson tells the others of his search for Claire.

Back at the cottage, Claire wakes to find herself in another strange bed, watched over by another strange man. She is wary and mistrustful, but after greeting her cheerfully, supplying her with new clothing and inviting her to help herself to some food, Martin tactfully withdraws. Claire eventually joins him outside, and the two exchange stories, with Martin making painful reference to his lost wife and children. When Claire intimates that she intends leaving her refuge – “To see what is left of the world” – Martin warns her of the roving band of men, of Jephson’s presence, and of the dead woman on the heath; he then invites her to stay with him. Disliking the sense of compulsion but left with little choice, Claire accepts – for the present.

Meanwhile, those twenty miles away, the community of survivors of which we have heard are making only desultory efforts at rebuilding the shattered town that they occupy. In a foreshadowing moment, one elderly resident, after remarking sourly about people who seem to think they’re on vacation, adds that what is needed is, “Someone to take them in hand and knock some sense into them.”

One survivor who is working hard is a man called Tom, who returns to his house carrying chickens for dinner and a bucket of water, which he intends for the care of his houseguests: Helen Webster and her children…

There is some question about the correct running-time of Deluge. The IMDb lists it as seventy minutes; the website for its post-recovery VHS release has a running-time of fifty-nine minutes; while my own print runs about sixty-four. It seems certain that some footage has been lost, even if we cannot be certain how much. This is felt most strongly in the immediate wake of the catastrophe. We never know, for example, why Martin is so certain that Helen and the children are dead, or how they came to be so widely separated in the first place.

An additional problem is the dubbing and subtitling of the dialogue, which makes its most serious impact in the scenes between Martin and Claire, Helen and Tom, as they debate and reconfigure their relationships. The subtitles are in any case substandard, full of misspellings and grammatical errors and dialogue drop-outs, and the occasional outright blooper.

(My favourite comes as the disaster is just about to strike New York when, after announcing Terrible earthquake along Pacific coast and Millions dead and Indescribable damage causing havoc everywhere, the broadcaster adds, There’s no cause for panic.)

Aggravating this, however, as various Italian-speaking viewers have attested, is the fact that the subtitles we do have are a poor translation of the spoken dialogue…and we have no way of knowing how close that was to the original script in the first place. The only thing that is certain is that a great deal of nuance has been lost, which is a pity because, after the disaster itself, this re-imagining of society after Sydney Fowler Wright’s vision is certainly this film’s main point of interest.

In Wright’s novel, surviving men outnumber surviving women four-to-one. No explicit explanation is ever offered to account for this outcome of the disaster, one that seems all the more unlikely considering that his story was based in a post-war, gender-imbalanced society in the first place.

There is a passing reference in the novel to the extra “ruthlessness” of men, possibly implying that when the catastrophe hit, the men saved their own lives while the women lost theirs trying to help others. At the same time, novel-Claire abandons her husband, an invalid in a nursing-home, with barely a backward glance. Since much of Wright’s social theory involved the winnowing out of the weak – sorry, the degenerate – presumably this piece of female ruthlessness carried authorial approval.

It might be expected that in a world requiring complete rebuilding, women would achieve parity as a matter of course; but Sydney Fowler Wright had other ideas. It is Tom, talking to Helen, who spells out the new state of social affairs: that with so few women and so many men, no woman has the right to have no man; she can choose a man for herself, or one will be chosen for her; no third option. This arrangement – this “passing of a new law” – is the work of the men, and if any of them objected to the idea, we never hear of it. The women themselves were, of course, not consulted.

This, then, is the brave new world of Sydney Fowler Wright: where in a matter of minutes, the female sex is reduced to the level of a commodity, with no future beyond the choice between voluntary concubinage or rape; not rising of necessity or election to a position of equality, but rather reduced to one of slavery; mere breeding stock. And it is also part of Wright’s vision that the surviving women – who, naturally, are all of reproductive age, and physically attractive – see no particular reason to protest.

(And it is not only the women who get short shrift in Deluge, although I can’t blame anyone but the film-makers for this one: amongst the survivors are a black couple, who seem written into the story primarily to reassure us that even a catastrophe won’t entirely change the world, and that whatever comes, black people will still be lazy and stupid. Oh, and to give the nice white people someone to laugh at condescendingly. Brave new world, indeed.)

Remarkably, the film version of Deluge follows the novel quite closely – apart from upping the ante even more, its advertising art trumpeting luridly, TEN MEN FOR EVERY WOMAN – and no law known except desire! – but, at least in the surviving version, it spends a lot less time discussing the details.

Tom explains the new facts of life to Helen, with whom he has fallen in love, adding that she cannot stay in the settlement without choosing a man. She, however, continues to insist upon her belief that Martin is still alive. She’s right, of course – and he’s busy falling for Claire – and, from one perspective at least, rightly so. As she and Martin sit companionably in a sunny grove, Claire gives an account of herself and her old life (which, in this version, does not involve an abandoned husband or a dead baby): a Wellesley graduate, with ambitions of being a flier, but who ended up a champion swimmer instead.

We need more movie women like this, people.

This idyll is rudely shattered by the reappearance of Jephson, who strikes Martin down and abducts Claire. Martin catches up with the two some hours later, in camp with Bellamy and his men, and succeeds in freeing Claire and stabbing Jephson, although not fatally.

A desperate chase follows, with Bellamy’s gang pouring into the woods in pursuit of the fleeing couple. Martin and Claire manage to escape back to their refuge, however, with Martin insisting that they spend the night in the tunnel where he keeps his scavenged provisions, reasoning that anyone searching for them will attack the cottage first and thus give them a chance to escape. The two of them bed down for the night…and Martin makes an impassioned declaration, pleading with Claire to make her home with him permanently. “All that is in the past – you are all that I have and all that I want.” And Claire returns his embrace…

But danger is closing in. Bellamy’s men, following Jephson’s directions, attack Martin’s encampment, meaning to kill Martin and seize his possessions – Claire included. They themselves, however, are the object of another attack. At the settlement, the body of the dead woman has been discovered, and the men agree that driving out Bellamy and the others is not enough: they must be exterminated. And so even as Jephson, Bellamy and the others lay siege to the tunnel, the men of the settlement, under the leadership of Tom, close in for a kill of their own…

(The experienced genre-watcher may feel a strange sense of déjà vu throughout this extended sequence of abductions, pursuits and battles, which were not only filmed – surprise! – in Bronson Canyon, but over the exact same ground later put to similar use in Invasion Of The Body Snatchers.)

When the smoke clears, Bellamy and his gang lie dead. So too does Jephson – killed by Claire, as he tried to strangle Martin. The two of them, bloodied and exhausted but in one piece, stagger out of their refuge to confront their rescuers, and Tom learns that Helen’s instincts about her husband were right all along.

He says nothing, however, but invites Martin – who introduces Claire as his wife – back to the settlement. In return, Martin offers up his store of provisions for general use. Thrilled to be safe, and to be amongst something of a society again, Martin and Claire laugh and joke – only for both of them to have the smiles abruptly wiped from their faces when Martin spies two small children playing in the street. His shock turning to joy, Martin embraces and kisses the pair, then asks after their mother, turning his back upon the stricken Claire without a word as he follows their pointing fingers. It is left to the similarly bereft Tom to put a consoling arm about Claire’s shoulders, and to direct her to a different shelter, somewhere she can hide herself.

Although both the novel and the film reach this impasse, their resolution of it could not be more different. One thing that they do retain in common, however, is their language. It is notable, and rather startling, that in this post-apocalyptic world, there is no religious presence at all – and nor do any of the characters seem to feel the need of one. The restructuring of society is carried out without even a glance at the old mores and moralities; women are handed to men without debate; Martin and Claire, having slept together voluntarily, consider themselves married. But Martin already has a wife; a “real” wife.

In the novel, the public revelation of the relationship between Martin and Helen means, as far as everyone else is concerned, that Claire is available to all the other men, and she is offered the same blunt ultimatum: choose or be chosen. And choose she does, but not as any of the others expect. Incredibly, in a story that turns upon the enforced distribution of women, in which men prove themselves only too willing to fight and kill for the possession of a single woman, we are expected to believe that Martin Webster will be permitted to have two.

But this is exactly how the novel resolves its dilemma, with Martin – who, having ruminated over the matter, concludes that polygamy is an “acceptable” arrangement, but polyandry is “monstrous” – offered the prospect of a ménage à trois with warrior princess Claire and domestic goddess Helen: the two women having discussed the situation and agreed between themselves that this situation will constitute “one honour for both”.

It is debatable whether this hilarious piece of masculine wish-fulfilment comprises a better or a worse ending to the story that the one offered up by the film version of Deluge; better, I suppose, at least in some ways; at least it preserves Claire. Of course, there was no way on earth that a film of this time, even one released in the pre-Code era, was ever going to get away with even the suggestion of a threesome, least of all one proposed seriously as a workable domestic arrangement.

(Which is to say, that although Ernst Lubitsch got away with it in Design For Living, that was a comedy, and comedies always were given more leeway; and besides, his film gets by on the not-exactly-credible suggestion that while the three characters are living together, they’re not sleeping together.)

Here, someone is going to be the loser – and there is very little question as to who that someone will be. As in the novel, Helen is made aware of the relationship between Martin and Claire – he confesses it to her, admitting that he loves Claire, even as he has told Claire that he loves Helen – but only in the film is there a big confrontation scene between the two women as a consequence.

By one of those curious rules of movie morality, the very fact that there is a confrontation means that Claire has already lost. (In the same strange way, when Claire was talking about herself earlier, every word that made her a better and a more interesting character also made it more certain that she was ultimately going to lose out.) It is Helen who forces the issue, asking if the two of them cannot discuss the situation, and try to come up with some honest solution?

Movie-Claire does not react as novel-Claire does, however. Instead she announces her intention of fighting for Martin no matter what; that she considers herself as much Martin’s wife as Helen is; that she doesn’t care about Helen, or even about the children. This speech essentially serves as her epitaph.

While the womenfolk are thrashing out their – and his – domestic problems, Martin has set about making himself indispensible to his new community, and soon proves to be that “someone” they were wishing for earlier, capable of taking charge and knocking the embryo society into shape. In a town meeting, Martin is formally offered the position of leader, and formally accepts. Helen then proves herself the perfect politician’s wife, clinging to Martin’s arm, gazing up at him adoringly, and offering no opinion more controversial than, “Oh, darling, I’m so proud of you!”

This little scene is enough for the watching Claire, who turns on her heel and strides away, even as Martin begins to search the crowd for her. He pursues her, increasingly desperate, but by the time he reaches the water Claire is gone, her clothing left once more upon the shoreline as she strikes out towards a very uncertain future. Given what we have already seen of “the rest of the world”, it is difficult not to view this as being, one way or the other, a suicide…

And here, I think, we hit upon the true cause of Deluge’s disappearance and near-loss. Although at the time there was no such thing as television or video, many movies were released to the cinema more than once. However, from 1934 onwards, before they could be so they had to meet the new demands of the Production Code, belatedly enforced. Thus, while some films were passed uncut and some were re-released censored, some didn’t even bother to make the attempt – including, in all probability, Deluge.

Barely a single aspect of post-apocalyptic life in this film would have passed the censor, from the big stuff – the reshaping of society, Martin and Claire shacking up, Claire’s possible suicide – to the small, like the amount of time Claire spends onscreen in her surprisingly brief underwear. The destruction of the world as we know it might have been an acceptable story element under the Hays Code, but don’t expect anyone to get away with a woman showing her naval.

It is a sign, I suppose, of how much faith the producers put into the ability of their special effects sequence to carry their film, that they were willing to entrust the acting scenes to a rookie director. This was the first feature film directed by Felix E. Feist, at the age of only twenty-three; he would go on to lengthy if not particular distinguished career in both film and television, one probably highlighted by the seminal Lawrence Tierney noir, The Devil Thumbs A Ride – although he also co-wrote and directed Donovan’s Brain.

Feist was the son of MGM executive Felix F. Feist, which probably explains how this independent production managed to secure the services of top cinematographer Norbert Brodine, who contributes some beautiful photography, particularly during the scenes immediately following the catastrophe, and at the end.

Like most disaster films, this really isn’t an actor’s movie, but without question the show is stolen by the lovely Peggy Shannon. Tragically, post-Deluge, Ms Shannon’s career, quite inexplicably, went nowhere; she became an alcoholic and died young, possibly (painful irony) a suicide. Otherwise, most of the cast is made up of second- and third-tier character actors, with the only really familiar faces here being Sidney Blackmer and Edward Van Sloan, who has a brief supporting role as the head of the Astronomical Society.

But of course, the significance of Deluge lies elsewhere, in the establishing of an entirely new movie genre…even if this is only evident in retrospect. It is fascinating to reflect how many of what we now consider the clichés of the genre put in an appearance here, right down to the obliteration of New York, that most long-suffering of cities. However, although the film was popular with the public, and a financial success, it was not immediately influential – except for those unforgettable special effects, which continued to have an impact upon cinema-goers for a full two decades after their first appearance.

It would be almost forty years before the disaster movie really found its feet – and then, like the characters in Deluge, almost without warning the world would find itself completely inundated. Given the extreme rarity of this film, and that it was not made available to the public until 1989, I suppose it is unlikely that Deluge was a direct influence upon the disaster films of the seventies, that decade of destruction—although personally, I like to imagine that Irwin Allen, a New Yorker by birth, caught a screening of it while still in his teens – and came away scarred for life…

New York does get hit a lot in these movies, but Los Angeles comes in a close second. And, of course, if global devastation is needed, Seattle’s Space Needle and the Eiffel Tower will have to go.

LikeLike

ps. I would love to see a movie set in Arizona, up in Flagstaff. The San Francisco Peaks are dormant volcanos. Let’s see them brought back (probably by EEEVIL corporation pollution). Northern Arizona University can provide plenty of college students for destruction.

LikeLike

I consider it ridiculous and hurtful that it took until Godzilla: Final Wars for Sydney to get trashed. C’mon, we’re nothing but recognisable landmarks! 😀

But apparently you’re even worse off in Arizona. Reactivated volcanos work for me! (Fracking?).

LikeLike

I think you’re correct that the biplanes are Sparrowhawks, especially if they “hook up” with USS Macon. Not a job for the faint-hearted!

And yeah, two women for one husband: Good! Two men for one wife? Unthinkable! I lead a Poly lifestyle myself, but many males seem to think that relationship = possession, rather than companionship, so it takes a rare individual to make it work.

LikeLike

Really, when you think about it (“So don’t think about it.”), from the perspective of ancient times, when people commonly considered childbearing to be the primary purpose of marriage* (a few think that even now, but never mind them), polygamy is just plain more purely “practical” than polyandry. If one man has X number of wives, that’s the number of pregnancies that can result from that marriage at one time. No matter how many husbands one woman has, THAT marriage will NEVER result in more than one pregnancy at a time…

The same would be true from the perspective of re-populating the earth (presuming that one considers that a GOOD idea…). The only way to get lots of children is to have lots of pregnancies. Any other social issues aside, it’s really just that simple.

Neither perspective currently dominates western civilization, and thus polygamy and polyandry are viewed as more or less identical concepts.

According to an episode of “Law & Order: Special Victims Unit” (“Snitch,” airdate 12/04/07), in northern Mozambique, it’s legal for one woman to have many husbands. So, depending on how reliable you consider such a source, there’s that, anyway.

It occurs to me that while it’s illegal for a man to marry a lot of women and father lots of children by them, it’s perfectly legal for a man to father lots of children by a lot of women that he’s NOT married to. Unbecoming, perhaps, but legal. Really makes you think, don’t it? Or not, not works too. 😉

===

*The underlying premise there seems to be that if you’re not going to have children, what’s the point of getting married in the first place? And there may be something to that…

LikeLiked by 1 person

The only reason *I* can see to get married is for the things like being able to see a gravely ill spouse in hospital, things like that. Those are some of the big reasons we fought for legal Same Sex marriage.

Never say Never, but I doubt I’ll evers get married, myself.

LikeLike

The right not to get married is just as important, in its own way.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I won’t argue. 🙂 I don’t want to be a possession, chattel, a brood mare, or dependent on someone else to hold my property or assets.

LikeLike

“This morning’s unprecedented solar eclipse is no cause for alarm.”

I see Wright as a link in the chain between Rousseau and those survivalist types in the eighties who seemed rather to be looking forward to the end of the world as a chance to prove how manly they were. Yes, being civilised makes you unfit to look after yourself outside civilisation… because instead of spending hours every day just looking for food, you can spend that time doing something more interesting.

Sparrowhawks on the Macon, certainly, but the ones on the flattop may well be F4B-1s (Navy version of Boeing P-12s); as far as I know the Sparrowhawk was only ever used with airships. (I see an interesting parallel with “the Air Force Flying Wing” in the George Pal War of the Worlds: cutting-edge technology, ooh shiny, but it’s still helpless against the problem.)

That idea that population numbers are more important than anything else is alien to most modern mindscapes, but I get the impression that in the 1920s-1930s it was still something people cared about in the mainstream.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I still see that type around, Roger. There are a class of people that seem to live as if their lives were an action movie, and if they are prepared enough, they can be John ‘Die Hard’ McClane or ‘Mad’ Max Rockatansky. I had a friend that collected guns, and one of his friends was a delivery driver with a Concealed Weapons permit, always armed & ready for terrorist attack or, and I quote: “Zombie Apocalypse’. How I wish I were kidding.

There is also a class of folks that live in dread of one unlikely Doomsday scenario or another. Nibiru, Solar Flares, Chinese invasion, take your pick. Why work on making the world a better place, when you can wait every day for The End?

LikeLike

Kind of related to something I don’t quite get about some post-apocalyptic films: Why do the characters even WANT to survive? Most of their friends and relatives are dead. Society as they know it as ceased to exist. Their lives are CRAP. When you ask yourself “what’s the point?” and it turns out there IS none, well…sooner or later you’re going to die no matter what, so…

That’s just me, of course.

LikeLike

ronald – yes, there are answers to that question, and seeing a character think about those answers is one of the reasons I enjoy stories of any kind. When a film just assumes “we want to survive because it’s what heroic protagonists do” I feel cheated.

LikeLike

Yes, “civilisation” is a leveller that allows for the privileging of different skills, so let’s wipe away civilisation. What the survivalists don’t seem to grasp is that if they get what they’re praying for, who survives is going to be a complete crapshoot in which “preparedness” is no protection. Although the actual survivors will probably be grateful for your hidden caches, after the event.

Population and reproduction questions were HUGE in the 20s and 30s, nastily enough in the context of eugenics. This was the time of enforced sterilisation, so it wasn’t just about reproduction, but the right sort of reproduction. Stories like this take it for granted that the “right” sort of people will survive and reproduce, which in the long term will “fix” everything.

Coming at this with a female-biologist perspective makes for uncomfortable viewing. I look at this scenario and immediately conclude:

1. Cholera.

2. Mosquito-borne disease.

People in cooler climates will do better but the disaster ain’t over just because the earthquakes and flooding have stopped.

Male-authored disaster stories rarely seem to think further than repopulate, repopulate, repopulate, but unless you stop for a while and clean up the world you’re living in, far from repopulating you’re going to kill off the few women you do have.

LikeLike

They’ve probably never seen floodwater. It’s brown, folks. (OK, so was the Yarra River when I met it, but I hope not for the same reason.)

The survivalist types always think that they will be the ones to survive, of course – it’s usually a harmless fantasy, like “if only this train crashed I could be brave and save that pretty girl”.

LikeLike

I’d guess that most of us that saw “Mad Max” imagined ourselves in similar scenarios, but I’ve met people that seem to be looking forwards to it, and have been verbally abusive towards me in that regard, like “you won’t have time to be [Lesbian] after the nuclear war, Missy” (and worse) So, the people that look forwards to the “right sort” of survivors are still with us.

IMHO, if that kind of thinking is what’s left after a true calamity, then I don’t want to survive, and I don’t think the human species would have any future worth noting. Much better I think to try to make positive changes now.

LikeLike

Not to mention that constant pregnancy/childbirth is going to kill off the majority of the women anyway, along with a lot of the infants, and those who survive the actual birth process are most likely going to keel over from severe malnutrition and disease. I love how the male authors of these tales think conception/gestation/birth is just a matter of a few pushes and some hot water.

LikeLike

…and if it’s not, well, that’s just because we’re degenerate, civilised women! 😀

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: Feeling a bit disastrous « The B-Masters Cabal

Lyz: “The right not to get married is just as important, in its own way”

Well, of course, but in contrasting polygamy and polyandry, that’s kind of beside the point (I doubt that any society that accepted polygamy or polyandry as a norm embraced the idea of men or women spending their lives unmarried). Except as it relates to a man who fathers lots of children by a lot of women that he’s NOT married to, I suppose.

When you think about it (“So don’t think about it.”), if such a man shared a home with those women and those children, without marriage, they’d be practicing unwed polygamous cohabitation. Meaning that even polygamous marriage is susceptible to being “unsanctified” OSLT.

Then again, just because those women had sex with that man at least one time each, that’s no guarantee that any of them would be interested in doing so again, meaning that such a household could, I suppose, constitute polygamy not only without marriage but even without sex.

Which would beg the question of why the man and the women would move in together to begin with, with the obvious answer being: For the sake of the children (hey, the more Moms, the better, am I right? am I wrong?). Who were at one point considered the raison d’etre for marriage itself. Really makes you think, don’t it? Or not.

ANYWAY, according to another ancient school of thought, one should never even HAVE sex unless one is married (to the one with whom one is in fact having sex). How much family dysfunction, in all its many forms, have resulted from THAT point of view?

LikeLiked by 1 person

“I’d guess that most of us that saw “Mad Max” imagined ourselves in similar scenarios”

Yet even in such a horrific situation, some would probably look at it as “At least I get three meals a day and a roof over my head, that’s a better deal than I’d get out in the wastelands. At least I don’t have to fight for survival every day, kill or be killed. At least I’ve got the guarantee that I’m only going to be raped by ONE man* instead of god knows how many more.”

It all depends on just how much one wants to survive and, as RogerBW noted, some people just don’t question whether or not survival would be worth it.

Some people would strive to survive after the apocalypse just out of hope that they’d live long enough for the Rapture…

Even the women in the milking machines (who were, I’ve received the impression, in such tight restraints that they couldn’t have killed themselves if they’d wanted to) might take an “hey, at least I’m ALIVE” attitude…if only to keep from going insane by thinking too much about the whole thing. A variation of Stockholm Syndrome: “It could always be worse.”

Then again, it’s like John Carter of Mars, who was in and out of seemingly hopeless situations all the time, said: “I Still Live!” because while you’re alive, it’s at least REMOTELY possible that your situation might change for the better (which it actually did for the “breeding” women). When you’re dead, not so much.

===

*I haven’t seen the film but I’m presuming that the villain keeps his harem-ites from being victimized by other men. I could easily be wrong.

LikeLike

Well, I was speaking of “Mad Max”, the first one, where we see society wind down while they still have police, ice cream, and vacation trips. You gotta understand, I’m stuck in a region where the neighbors tried to get me evicted from my apartment when I came out, and I carry Pepper Spray on my key ring while I check the mail.

No, I don’t welcome societal disintegration, nor do I yearn for Armageddon. But I’ve been threatened by people that believe *I* represent a breakdown of society. These things aren’t academic to me.

LikeLike

I apologize if I spoke inappropriately.

LikeLiked by 1 person

No need for apology, Ronald. 🙂 I think making people aware of certain issues is of value, though. And it’s certainly not all bad. I get compliments on my fashion choices from strangers, and there are elderly people in the area that get a big smile when that Tall Gay Girl holds a door or helps them carry an item. I wear Pride jewelry always, as a statement, and as a challenge.

LikeLike

(I’m presuming that this post will manifest below your post which responded to my apology; if not, well, them’s the breaks.)

Not that I’m in any position to tell you anything about anti-gay sentiment, but I think some of it’s based on a tendency to, when a person comes out, just *presume* that means that said person has a sex life (which of course isn’t always the case at all). Some people simply don’t want to acknowledge just how many unmarried men and women have sex lives…often because they themselves don’t. I’ve noticed that some TV shows seem to take it for granted that most single people have sex lives and, hey, TV shows wouldn’t LIE to us about something like that, would they? 😉

The opposition to same-sex marriage is probably based on similar lines: The fact that marriage is so important to gay couples implies the kind of deeply felt, dedicated, “one and only” true love (I’m idealizing things just a bit, I realize that) which some homophobes have never experienced and never will, not in their own marriages and not in any other capacity.

Supposedly, enlistment in the US military is down, yet gays fought to be allowed to serve in the military. Supposedly, the number of people on welfare is on the rise, yet gays have to fight for the right to keep their jobs. Supposedly, heterosexual marriage is on the decline, yet gays fought for the right to get married. Supposedly, church attendance is down, yet gays fight for the right to be included in religious communities. There are thousands of children without parents (no “supposedly” there), yet gays have to fight for the right to adopt. Gays seek the very rights that “right-wingers” bemoan are vanishing from America (and which many of them aren’t upholding very well themselves); gays are the ones emphasizing the importance of “traditional family values.” Really makes you think, don’t it? Or not, not works, too.

All of this is entirely off-topic so far as the film review goes, of course.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Well, I think you’re partially right. Some, or a lot of it though, is the “Othering” that people do. “She’s different, he’s different, I’m afraid of what makes them different, so I’ll oppose them, and I wont be afraid”. I think that humanity needs to think about these things, and quickly: Fear, hate, change, being wrong, being lied to, dehumanizing others. I’m a historian by avocation, if not formal training, and I’m seeing parallels to some very dark periods in history. I truly don’t believe we have much of a future as a species if we don’t examine assumptions and make better choices. More to the point of this film and this review, I do think that a great many people either secretly or openly hunger for destruction, for Armageddon in one form or another. It’s a fantasy of avoidance, of escape, and for some, dehumanization. I hope we as a species can make better choices and work towards something better.

LikeLike

Apropos of nothing except the concept of trauma (of which Stockholm Syndrome is of course an aspect), you know what it occurs to me might make for a good movie? Seeing how Sally Hardesty psychologically recovered from the events of “The Texas Chain Saw Massacre,” a psychological drama showing how she gradually got to the point where she could live something resembling a normal life again. Ye, that’s what it occurs to me might make for a good movie, all right. Don’t give sequels to the slashers, give them to the Final Girls!

On a related note, what do The Prey (1984), Simon Says (2006), and The Hills Run Red (2009) have in common? At the end of all three, it was revealed that the surviving girl had given birth to, or was pregnant with, the slasher’s child[ren], having been imprisoned in the interim. Nine months with a slasher. Eew. How does one come back from THAT? Yet in real life, any number of women HAVE indeed come back from that, or at least lived through it. Alba Alvarez, Amanda Barry, Jaycee Lee Dugard, Elizabeth Fritzl, Lydia Gouardo, where are THEIR movies, Hollywood?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Anyway, KIND OF back on topic: When you think about it (“So don’t think about it.”), the existence of sperm banks in at least fourteen countries, hundreds of them in the United States alone, has in effect made men irrelevant to the propagation of the human race. If every male on Earth disappeared, there’d be more of them in nine months or so.* In contrast, if every female on Earth disappeared, well, that’s it for humanity, then.

At least (and here I go on another tangent) one theory about Leviticus’s prohibition of male homosexuality is that it was at least partially based on the ancient Israelites’ desire to keep their culture from being “polluted” by neighboring tribes, to make sure their people remained — well, awkward though it may sound, especially in relation to Judaism, there’s really no other way to say it — “pure-blooded,” so any “waste” of Israelite semen was considered taboo (that’s also why the prohibition on masturbation; see, from a millennia-old xenophobic perspective, it’s all perfectly “logical”). Ever notice that Leviticus doesn’t say a thing about prohibiting lesbianism? That’s why, because, to be blunt, lesbianism doesn’t involve sperm. Since Christianity, at least, is not centered around preserving Israelite cultural identity (that’s part of what made Jesus so controversial, because Jesus proclaimed that the word of God was open to *anyone*, whether man or woman, whether slave or freed…whether Jew or Gentile) and, even without sperm banks, humanity hasn’t been in danger of running out of sperm for quite some time now, it should be obvious that Leviticus’s prohibition is no longer relevant.

I *VERY* much regret it if any of the above comes across as anti-Semitic; that’s not at all my intent. Things were just different thousands of years ago, that’s all.

===

*Unless women of the post-male world decided to “screen out” the births of male babies and “allow” only the births of female babies…a policy that sounds far more sensible than it should. IMHO.

LikeLike

Well, it’s been argued that one of the reasons for the dietary laws – which aren’t the same as those of other groups in the same area at the same time, so the public health argument doesn’t entirely work – was to stop people from casually sitting down to eat with their out-tribe neighbours. Which is, let’s face it, why today we know who the Jews are, and don’t know about any of those neighbours: they kept separate rather than blending into the general tribal mélange.

Back on topic a bit more, the first pregnancy from frozen sperm was in 1953, so that’s a fairly narrow window in which it’s relevant. (This became big news in 1954 for various reasons, and I wonder if there are any after-the-bomb SF films from that period that consider it an important subject.)

LikeLike

Well, I said “has in effect made” but I didn’t imply that it had so “made” as long ago as 1933. 😉

LikeLike