“They are not men, M’sieur: they are dead bodies – zombies! – the living dead. Corpses taken from their graves, and made to work in the sugar mills and fields at night…”

Director: Victor Halperin

Starring: Bela Lugosi, Robert Frazer, Madge Bellamy, John Harron, Joseph Cawthorn, Brandon Hurst, Clarence Muse

Screenplay: Garnett Weston

Synopsis: In Haiti, Madeline Short (Madge Bellamy) and Neil Parker (John Harron) travel towards the estate of Charles Beaumont (Robert Frazer), where they are to be married. Their coach stops suddenly. Ahead, a native ceremony is under way; a funeral. The coach-driver (Clarence Muse) explains to the newcomers that in fear of grave-robbers, the locals sometimes bury their dead in the road, so that they may be protected by the passing traffic. The coach moves on, only to stop again to allow the driver to ask directions of a man standing by the road. The man, Murder Legendre (Bela Lugosi), does not answer, but leans into the coach, staring intently at the frightened Madeline. At that moment, several figures emerge from a nearby cemetery. With a cry of, “Zombies!”, the driver sets the coach in rapid motion. As it drives away, Legendre snatches the scarf from about Madeline’s throat, tucking inside his coat with a satisfied smile. Arriving at the Beaumont estate, Neil takes the driver to task for his reckless handling of the coach, saying that they might have been killed. The driver tells him solemnly that they might have been worse than killed; that the men from the cemetery were not men at all, but zombies – the living dead, resurrected to work in the sugar mills. Several of these mysterious creatures are then seen passing over the crest of a nearby hill, and the driver flees in terror. The shaken Madeline recoils as a shadowy figure approaches Neil and herself – but it proves to be Dr Bruner (Joseph Cawthorn), a missionary who has been summoned to perform the marriage ceremony. Neil and Madeline explain to Bruner that Beaumont has been extremely kind to them both, insisting upon hosting their wedding, and arranging a job in New York for Neil. Bruner is surprised – and suspicious. Meanwhile, Silver (Brandon Hurst), the butler, goes to inform his master of his guests’ arrival. Initially, Beaumont orders his butler to announce that he is out – then changes his mind, observing that this might look odd. Silver agrees, telling Beaumont that Bruner has already voiced his scepticism of Beaumont’s motives. Silver also reports that there has been no word from “that man”, and then implores his master to abandon his dangerous plan. Beaumont tells him simply that if he can’t have Madeline, nothing matters. He then goes to greet his guests, alarming Neil with his warmth towards Madeline. As Silver shows the guests upstairs, Beaumont answers a knock at the door. From the balcony of his room, Neil sees Beaumont climb into a carriage – a carriage with a rigid, blank-faced driver. Beaumont is taken to a sugar mill, where more of these strange silent figures work, and enters an office, to be greeted by Murder Legendre. Beaumont complains of Legendre’s lack of action, insisting that if he had just one month, he could win Madeline’s affections away from Neil. Legendre scoffs at this, but insists that there are ways of preventing the marriage. Beaumont says wildly that if Legendre can do this, he may ask for anything in the world as payment. Legendre glances significantly at one of his zombies, whispering a few words in Beaumont’s ear – then forcing upon the horrified yet tempted man a small phial of a certain drug…

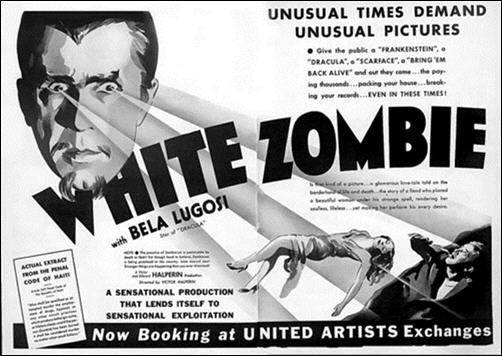

Comments: After the huge successes achieved by Universal Studios with Dracula and Frankenstein, the other studios and various independent film-makers alike, recognising that the public’s taste for “horror” was no mere flash in the pan, were swift to jump upon the bandwagon. In the early thirties, movie screens were flooded with tales of the macabre. Most of these were adaptations of existing literary sources, novels and stage-plays. One film, however, gave audiences something entirely new. In 1929, author William B. Seabrook published The Magic Island, a book on Haiti, and in it introduced the American public to the concept of the zombie:

“The eyes were the worst. It was not my imagination. They were in truth like the eyes of a dead man, not blind, but staring, unfocused, unseeing. The whole face, for that matter, was bad enough. It was vacant, as if there was nothing behind it. It seemed not only expressionless, but incapable of expression.”

The brothers Victor and Edward Halperin had both enjoyed moderately successful film careers during the silent era, Victor as a writer-director, Edward as a producer. In 1932 the two joined forces, and with a $50,000 budget and an 11-day shooting schedule, and working on leftover sets on the Universal and RKO lots, not only gave the world the very first zombie movie, but managed also to create one of the most remarkable horror films of its time.

With only occasional exceptions, such as Rouben Mamoulian’s startling version of Dr Jekyll And Mr Hyde, by 1932 the American horror film was still much as it had been at the dawn of the sound era: static, dialogue-heavy and, frequently, overly beholden to its material’s stage origins. The Halperins strongly disapproved of the state of film-making in general at the time, and of talking pictures in particular, and set out to make a film that harkened back to the silent era; a film with the story carried by its visuals, with minimal dialogue and stylised acting, and imagery informed by the Expressionism of the previous decade; a film entirely anachronistic, yet anachronistic as a deliberate artistic choice.

White Zombie almost defies conventional criticism. Much of the acting is bad – very bad; the sparse dialogue is, on the whole, equally undistinguished; yet these defects seem barely to matter when set in the context of the film’s superb style and eerie, dreamlike atmosphere. This is one of those rare films where, you feel, the planets must have aligned during production: nothing that any of the participants created in later years comes close to matching the technical virtuosity on display here. White Zombie is a minor masterpiece, a nightmare in chiaroscuro.

Right from its opening moments, White Zombie declares its intention to be a different kind of film. It begins, not with the standard credits, but with a scene; a native funeral, set at night and overlaid by chanting. Instantly, the viewer is swept up into the mood of the piece. Arthur Martinelli’s photography throughout is quite exceptional; this is one of the most visually beautiful films of its time. Although White Zombie is not classically Expressionistic, wonderful use is made of light and shadow, which adds immeasurably to its atmosphere and its air of menace.

The camera is also mobile. Particular notice should be taken of the unavoidably talky scene in which Neil learns the truth about Madeline’s fate. Scenes such as these, dialogue-bound, can be (and often were) a total mood-killer – but here Martinelli kept his camera moving, gliding, giving life to a sequence that otherwise would be very heavy going.

White Zombie also differs from many contemporary productions in its welcome determination to wring as much as possible out of its sets and its special effects. This attitude gives us not just the shivery scenes of the zombies emerging from the cemetery, or passing over the horizon at twilight, but the glass matte shots of Legendre’s castle, and above all the fabulous deep shot inside the hall of the castle, with the zombie Madeline playing the piano at one end of the room, and Beaumont, sprawled in a chair, listening to her, at the other – and all the details of the production design around and in between.

Care was also taken with the costuming. Befittingly, considering the deliberate fairy-tale quality of this film, everything tends to be spelled out in black and white. Legendre himself appears in a variety of outfits, sometimes hatted, caped and gloved, sometimes in evening dress, but always, always in black. More unusually, perhaps, the male hero, Neil Parker, is just as consistently dressed in white. As for Madeline, the White Zombie of the title, she spends most of the film clad in long white gowns that are part wedding-dress and part shroud, and which emphasise her position, trapped and unnatural, as virgin wife.

Ironically, considering the Halperins’ dislike of sound pictures, one of the most notable aspects of their film is its sound design. In those early days, the idea of a “soundtrack”, per se, was still a novelty. (Bird Of Paradise, the first film for which a wholly original score was written, was released the same year as White Zombie.) Consequently, White Zombie relies more upon existing, well-known pieces of music to create the desired emotional ambience – for example, using the spiritual, “Listen To The Lambs”, to convey the psychic reconnection of Madeline and Neil after the girl has fallen into the power of Charles Beaumont and Murder Legendre.

But it is the film’s sound effects that are truly worthy of notice, particularly, unusually for this era, in those scenes where the Halperins chose to impart information through sound rather than a visual. One such scene is Neil’s discovery that Madeline’s body has been stolen from its resting-place. We see the distraught, drunken young man following his vision of his lost love (his haunting by Madeline’s image is a clever piece of work in itself) all the way into her tomb – but we do not see his discovery of the violated grave. Instead, we hear Neil’s scream, high and agonised, echoing from deep within the mausoleum.

The most unsettling use of sound, however, comes during Beaumont’s visit to Legendre’s sugar mill – a scene equally unforgettable for its visual qualities. The mill itself is entirely staffed by zombies – silent, relentless, unseeing, uncaring. Against their silence, the grinding of the mill is doubly evocative – and doubly disturbing, particularly when one of the zombies stumbles and falls into the mill itself. The other zombies do not react, any more than the victim himself does: they go right on grinding, grinding, grinding…

As would prove to be the case for many years to come, the zombies of White Zombie pose little danger to the central characters in and of themselves. The horror of the story lies elsewhere, in the threatened loss of self; in the loss of the soul, if you prefer. As do so many horror films of this era, White Zombie centres upon the disruption of a new marriage, and the resultant spiritual and sexual jeopardy of the bride. Our heroine, Madeline Short, has travelled by sea from New York to the West Indies to join and marry her fiancé, Neil Parker. On the journey she meets Charles Beaumont, a wealthy plantation owner in Haiti, who develops an uncontrollable passion for the girl that drives him, while posing as her friend, to plot against her.

Hoping to win her affections for himself, Beaumont lures Madeline to his plantation by offering to host her wedding there, and by dangling an irresistible carrot: a promise to remove Neil from his position in a bank in Port-Au-Prince, and arrange for him a job in New York. However, unable to turn Madeline from marrying Neil, Beaumont succumbs to the temptation of placing himself in the hands of Murder Legendre, an “evil spirit man” of strange and dangerous powers, and demanding his help.

Lacking any specific literary or dramatic roots, White Zombie draws upon a variety of sources, shaping them to its own ends. Apart from William Seabrook’s book, the most obvious inspiration for the screenplay was the story of Faust. Bela Lugosi’s appearance as Murder Legendre is unmistakably Mephistophelian, and in the guise of helping Beaumont to attain his heart’s desire, the “spirit man” instead lures him, first figuratively and then literally, into selling his soul. When Beaumont and Legendre meet, the former announces that the marriage of Madeline and Neil is imminent, and complains that the latter has left it too late to take any action. We know that Legendre has taken action, and is in possession of Madeline’s scarf. His concealment of the fact is a calculated ploy on his part, intended to drive Beaumont to an act of desperation – which it does.

Another important influence upon White Zombie would seem to have been George Du Maurier’s novel Trilby, in which a free-spirited girl falls under the hypnotic power of a sinister musician, who finds that although he can control her every action, he cannot force her to love him. (The story was filmed only the year before as Svengali, with John Barrymore in the title role.) Svengali’s situation is one in which Charles Beaumont, too, finds himself – or worse. Although he has Madeline seemingly in his power, although he begs and pleads with her to respond to him, it is Legendre whom she obeys, gliding instantly from Beaumont’s side when the zombie master appears. Sick at heart, Beaumont undergoes the kind of enlightenment that, frankly, we do not see enough of, either in films or in society itself.

So often, physical beauty is held up as all that matters about a woman: it was a face that launched a thousand ships, we are told, not a heart or a mind or a spirit. By this standard, Charles Beaumont has everything that a man could desire: Madeline’s lovely shell is his to do with as he wishes. But it is not enough. “I thought beauty alone would satisfy me – but the soul is gone,” Beaumont mourns as he sits beside the empty-eyed, impassive figure in white, recognising too late that having sacrificed the inner woman to get her into his power, he has destroyed the very essence of what he loved.

Unfortunately for White Zombie as a whole, the power of much of this is severely undercut by the fact that the Madeline we see before she falls under Legendre’s spell seems to have precious little going for her by way of heart or mind or spirit. Madge Bellamy was an actress who had enjoyed success in the silent era – she played the female lead in John Ford’s The Iron Horse in 1924 – but who could not build a second career with the coming of sound. With their policy of making White Zombie a deliberate throwback to an earlier period of film-making, the Halperins’ casting of Bellamy is entirely understandable – and physically, she was well cast. However, as an actress she was quite unable to invest Madeline with the right kind of qualities.

On the contrary, Bellamy’s performance as the “conscious” Madeline is one of the film’s weakest aspects; while her flat and grating delivery of her opening line – “In the road?” – is enough on its own to jolt the viewer out of the dreamy mood created by the night-time burial scene that begins the film. Worse still is the scene in which – while escorting her to the altar! – Beaumont tries to talk Madeline out of marrying Neil: Madeline barely reacts to his fervent declaration of passion, finally uttering no more than a toneless, “Please don’t.” The result of all of this, much to the detriment of the film, is that we are left mystified as to why even one man should become so obsessed with Madeline, let alone two – or even, depending upon how one interprets Legendre’s behaviour, three.

Of course, many horror films from the early days of sound – and not just then, either – suffer from colourless and uninteresting central characters; but frankly, I’m not sure that the powers of “good” were ever more weakly drawn than they are in White Zombie. Matching Madge Bellamy’s inadequacies as Madeline, we have John Harron’s Neil, a “hero” who makes most of David Manners’ characters of this era seem vibrant and forceful by comparison. Neil’s rapid sinking into helpless drunkenness following Madeline’s “death” on their wedding day we can understand and forgive; but his subsequent faints and collapses (“fever”, don’t you know), just when he learns that Madeline can be rescued, are likely to inspire contempt rather than sympathy.

The third point of this uninspiring triumvirate is Joseph Cawthorn’s Dr Bruner, an exceedingly confused characterisation, being at once a most unmissionary-like missionary, the film’s Van Helsing substitute and – thankfully, just barely – the comic relief. One of the reasons that White Zombie plays well to modern audiences is, I think, that unlike many of its contemporary productions, its sombre tone is almost uninterrupted. Apart from a feeble running joke about Dr Bruner’s pipe, the film is mercifully free of “comedy”.

Bruner’s main function in the film – although he behaves more heroically than supposed hero Neil during the climax – is to carry the necessary exposition scene, in which he explains zombies to both Neil and the audience of the time, and reveals that the “dead” Madeline may be nothing of the kind. (Well – eventually. He actually starts off by breaking the cheery news that Madeline’s bones may have been used in native ceremonies.) It is Bruner’s knowledge, and Bruner’s relationship with the natives of Haiti, that allows for the rescue of Madeline – and it is Bruner who strikes down Murder Legendre at a critical moment, revealing how the zombie master’s grip on his slaves may be loosened. Yet for all this, he is no more memorable than our alleged hero and heroine.

It is an extraordinary feature of White Zombie that this character vacuum at its heart causes so little damage to the film as a whole. This is partly because this fundamental lack is well compensated for by the production’s technical excellence – but it is predominantly because the film’s critical performances, its critical characterisations, lie elsewhere. For all the apparent focus upon Madeline and the three men who desire her, White Zombie’s crucial relationship is that between Charles Beaumont and Murder Legendre.

Along with Madge Bellamy’s woodenness and John Harron’s invisibility, as Beaumont Robert Frazer offers up yet another incongruous acting style. However, while his florid, declamatory manner is occasionally jarring, it is not entirely inappropriate. We draw from it the sense of Charles Beaumont as a man of uncontrolled passions, one accustomed to his own way and entirely unused to being thwarted. In justice to Frazer, the fact that he has to act opposite Madge Bellamy’s negativity makes his performance seem further over the top than it is; while the contrast between Beaumont’s initial bluster and his slow, silent zombiefication is remarkably effective.

Having failed by fair means to win Madeline’s affections from Neil, Beaumont is quite prepared to resort to foul. His fatal error is assuming that he may simply use Legendre, not recognising that in doing so, he is placing himself in his co-conspirator’s power just as much as he putting Madeline there. Beaumont’s arrogance, his undisguised loathing of the man whose assistance he demands, is finally his downfall.

In growing despair over the zombie Madeline, Beaumont implores Legendre to change her back, to restore her soul; and Legendre agrees, offering Beaumont a glass of wine so that the two of them may toast “the future”. In his relief, Beaumont is, fatally, off his guard. We, on the other hand, remember only too clearly the original scene of temptation, in which Legendre handed Beaumont a phial of a certain drug, informing him in the most purring of voices that it needs, “Just a pin-prick…in a glass of wine…or perhaps…a flower?”

It was indeed a flower that spelled Madeline’s doom, a poisoned rose handed to her after her rejection of Beaumont’s declaration of passion. Here, thoughtlessly, Beaumont sips his wine…and that is enough. His horrified recoil, his awareness, comes just too late.

(If the horror films of the thirties teach us anything, it that we should never drink…wine.)

There is much in White Zombie that probably shocked audience of the 1930s: Madeline’s plight; the zombies themselves, with their lack of will and their unnervingly blank faces (make-up by Jack Pierce); the physical horror of Neil’s point-blank – and wholly ineffective – shooting of one of the undead horde. Today’s audiences will probably be unmoved by these things; they may even find them a little – quaint.

Yet there is a scene in White Zombie that is one of the most chilling of its decade, and which to my mind has lost none of its power to disturb, even to this day. Whether Legendre has deliberately lowered the dose, or whether Beaumont’s mere sip of wine is to blame, we cannot be certain; but the effect of the ingested drug is tortuously slow. Beaumont slips into the zombie state inch by agonising inch – and remains fully conscious, though unable to speak, throughout. And before him sits Murder Legendre, carving the wax effigy needed to complete Beaumont’s subjection to his will. With one last effort, Beaumont forces out his hand, clasping Legendre’s own in a gesture of heartbreaking desperation.

And Legendre smiles. “You refused to shake hands once. I remember,” he comments, calmly freeing himself before uttering these unforgettable words, words both seemingly innocuous yet deeply unsettling: “Well, well…we understand each other better, now…”

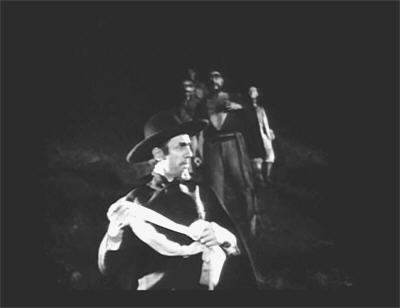

Along with its technical brilliance, the outstanding feature of White Zombie is the performance of Bela Lugosi as the fabulously named Murder Legendre, which is certainly one of the three or four best of his career. The vagaries of Lugosi’s professional and personal lives would in time lead him into situations both painful and embarrassing. Although he was frequently the best thing about the films he appeared in, watching those films is not always a comfortable experience. The satisfying quality of White Zombie stems from the fact that both as a film and as a vehicle for Lugosi, it can be enjoyed without reservation – not least because Lugosi was so obviously enjoying himself. Furthermore, his evident pleasure in his own performance colours his characterisation of Legendre, who displays throughout a candid pleasure in his own capacity for evil.

Obviously cast for his performance in Dracula (and having already shot himself in the foot professionally, handing Frankenstein’s Creature over to Boris Karloff), Lugosi’s supposed “hypnotic” personality is exploited to the full by the Halperins. The very first we see of Murder Legendre is his disembodied eyes, superimposed over the landscape through which Madeline and Neil are travelling; a shot that conveys instantly the scope of the man’s powers, and the threat to the young couple who have so unwisely entered his domain.

With his dialogue restricted by the Halperins’ film-making policy, Lugosi is able to wring the maximum effect out of every malevolent word that he utters – and indeed, White Zombie gave to the world another of those endlessly quotable Lugosi lines. At the climax of the film, Neil and Dr Bruner invade Legendre’s castle in an effort to rescue Madeline, and Neil finds himself confronted by zombie master’s personal staff of the undead. “What…are they?” he stammers. “For you, my friend,” Legendre / Lugosi shoots back, relishing every syllable, “they are Angels of Death!”

In the pre-Production Code era of the early thirties, horror films were frequently transgressive in a way that, in my opinion, they have hardly ever been since. White Zombie sits a little uncomfortably amongst its brethren in this respect. While the film is certainly transgressive, there is an odd sense that it is so almost against its will. The sexual possibilities of Madeline’s enslavement cannot help but be there, but they are strangely unexploited. It is not until Beaumont pleads with Legendre to restore her to normality that the full horror of Madeline’s absolute helplessness is fore-grounded. “I have other plans for Mademoiselle!” Legendre retorts ominously – adding a few moments later, and with a most alarming gleam in his eyes – as if the Halperins felt they might as well be hanged for a sheep as for a lamb! – “And I have taken a fancy to you, M’sieur!”

(That last line perhaps explains why the film never touches, even by way of the most distant allusion, upon the question of whether one or both of these men have had their way with the helpless Madeline. To have done so would also have thrown an unacceptably clear light upon Legendre’s subsequent plans for Beaumont.)

On the whole, however, both Legendre and Beaumont seem more consumed by a lust for power than by the sexual kind – not that the two are unrelated, of course. Certainly Legendre’s choice of victims is informative. There is, inevitably I suppose, but still unfortunately, an undercurrent of racism in White Zombie. This may be a story of Haiti, but it is by no means a story of the natives of Haiti – even on the production level: Clarence Muse stands out like a sore thumb amongst the “black” characters in this film, many of whom are white actors in blackface.

The zombies who slave in Legendre’s sugar mills are given only a passing glance; it is the white zombies, they who form Legendre’s bodyguard, in whom the film’s horror is located. A former native witch-doctor is amongst them, true (and it was he from whom Legendre, via the use of torture, gained his knowledge), but the majority are former figures of official authority who threatened Legendre: a Minister of the Interior; the head of the Gendarmes; and the State Executioner! (The latter, played by Frederick Peters, is the be-whiskered, bug-eyed zombie whose image is most frequently reproduced in respect of this film.)

This emphasis seems to imply that for these things to happen to white people is automatically worse than for it to happen to black people – and for it to happen to a white woman is worst of all. Just take a look at the tagline on the lobby card reproduced up above: an inaccurate reflection of the film, perhaps, but an accurate one of the mindset of the time:

They knew this fiend was practicing zombiism on the natives…but when he tried it on a white girl, the nation revolted!

(All the same, Madeline’s fate is not the worst thing that could happen to her, apparently: when Bruner is revealing to Neil the various fates that could have befallen Madeline, the young man, a product of his time, reacts with an appalled, “In the hands of the natives!? Better dead than that!”)

It seems likely, though, that viewers of 1932 may indeed have sympathised specifically with the zombies trapped in Legendre’s sugar mill. Beaumont’s visit to Legendre takes him through the mill itself, and he is shaken by what he sees there – enough so to react with unconcealed disgust when a smiling Legendre suggests that he, too, employ zombie labour on his estate. Still smirking, the zombie master goes on to extol the virtues of his unwitting, insensible labourers: “They work faithfully – they are not worried about long hours!” – words, surely, to strike a Depression-era audience to the heart.

There is, on the whole, little overt politicking in White Zombie, although it is difficult to determine whether this is because this would have been in conflict with the Halperins’ conscious creation of a fairy-tale world, or whether certain grim realities were considered best avoided. In 1932, Haiti was still under US military occupation. Although slavery as such was not re-introduced, forced native labour was commonplace, while the white landowners who flocked to the country to take advantage of the situation rarely paid their workers more than twenty cents a day. Almost certainly it was under conditions such as these that Charles Beaumont rose to his position of wealth and power, which lends an interesting moral shade of grey to his instinctive recoil at the thought of zombie labour.

And what of the zombies themselves? One of the more intriguing aspects of White Zombie is the obvious uncertainty of the film-makers as to the actual creation of the zombies. Though ready to insist that such things can and do happen – and quoting the Haitian Penal Code to back up their claims – the Halperins hesitate over ways and means.

The gaining of power over an individual is variously posited as essentially “natural” (i.e. done through the use of drugs) and also the result of black magic. While Legendre’s drug is clearly necessary to the process of zombiefication, in the case of Madeline he further performs a ritual requiring a personal object, the scarf we see him steal from her in the opening sequence, and a wax effigy, which is thrust into a flame. Moreover, Legendre afterwards controls his captives’ actions via telepathy, a power he occasionally exerts over the normal, the living, as well.

Despite this three-level attack, it is implied that in some cases complete recovery by the victim may be possible. When Legendre finishes gleefully filling in the backgrounds of his personal servants, Beaumont demands to know what will happen, “If they regain their souls?” “They will tear me to pieces!” replies Legendre almost smilingly; the fact that the zombies may yet be capable of taking revenge on him seems a part of his pleasure in controlling them.

And ultimately, Legendre’s hold on his victims is uncertain enough to open a window of opportunity for they who oppose him. When Dr Bruner manages to creep up behind Legendre and strike him down, his brief unconsciousness is sufficient temporarily to free Madeline from his control. This is not the case for the rest of Legendre’s prisoners, however: in the end, the only act of free will on the part of the other zombies is self-destruction.

A generous reading of this would be that the probability of recovery diminishes with increasing time under control – but in truth, White Zombie has little interest in any of its undead but Madeline. This is an attitude that would prevail, too, in numerous films to come. For the first three decades of their screen careers, despite their constant star billing, zombies would be little more than set-dressing in their own films; the supporting cast, never the leading players. It would not be until the late 1960s that this scenario would begin to change – and ironically enough, as with the original introduction of the zombies to the cinematic world, this would be as the result of an imaginative, low-budget, black and white production made outside the confines of the Hollywood system. But that, of course, is another story…

Want a second opinion of White Zombie? Visit 1000 Misspent Hours And Counting.

************************************************************************************

A brilliant review. 🙂 This is my favorite Lugosi film, unless you count Martin Landau playing *as* Lugosi in “Ed Wood”. I can’t add much of value, except that I’ve seen references somewhere that until Romero, the “Zombie” movies were a kind of propaganda, each serving as justification in a way when the US Marines had to “pacify” backwards Haiti (to secure the profits of American corporations), somewhat similarly to how WW2-era movies didn’t flinch from “explaining” how awful the Japanese enemy was.

I like to learn the context around a film, and usually it doesn’t effect my appreciation for a movie’s quality, except that I can accept the racial overtones of “Gunga Din” more generously than I can when they are re-used in “Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom”.

LikeLike

I don’t think you can read the early zombie films like that, because most of them took zombieism away from its Haitian roots and gave the power to someone else—Nazis, most often. This film is really the only one to put everything in its correct context (though perhaps I need to take another look at I Walked With A Zombie); though that said, we can’t know how far audiences in 1932 joined the zombies / slaves dots.

Yes, we’ve discussed those sorts of things in the past, attitudes and racial impersonations—how much worse those manifestations become, the later they appear. I saw a bit of John Oliver last night talking about Hollywood “whitewashing” and the audience reaction was fascinating: they were clearly unfamiliar with how grotesque some of these “substitutions” have been, and just howled with disgust at clips of John Wayne, Marlon Brando and of course Mickey Rooney. Hopefully the message sank in, but…

LikeLike

I wish I could remember where I saw the reference about early Zombie movies. I haven’t seen very many of the early ones aside from “White Zombie”.

I’m glad for the reactions to “whitewashing” from that audience. I keep hearing that this-or-that studio or actor is talking about making a live-action version of some popular anime, and the reactions are usually “on no”, and “why do they think [such American actor] is *remotely* suitable for this iconic Japanese character?” So perhaps we’re making a permanent change in this regard.

LikeLike

I Eat Your Skin does fairly well with the context, too, if I recall correctly, regarding “voodoo” and zombies and what-not. As long as we ignore the howlingly stupid-looking zombies.

LikeLike

In a more modern setting, one could assume that Madeline is superlative in bed (which of course wouldn’t be shown, which is why we don’t see any reason for everyone to fall in love with her). But that hardly works here.

LikeLike

And she’s so lifeless even before she’s zombiefied…

LikeLike

Love it. His look is perfect. He is magnificent.

P.S. For those unaware, The Serpent and the Rainbow is an excellent film.

LikeLike

Just got the Kino Lorber Blu-Ray and loved it. There’s a 1932 interview with Lugosi on there that is a blast. What a character he was! Made me wish I could have met him in person back then.

I spent an hour putting together my own review of the film, but yours went into so much thought & detail, it put mine to shame. Great job!

LikeLike