“‘She’ offers to show them flames to bathe in, which gives one eternal life…”

Director: George O. Nichols

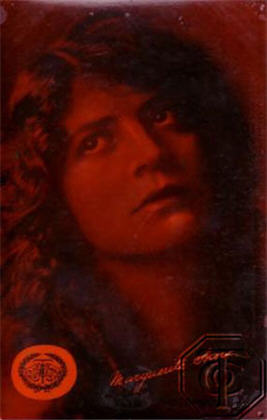

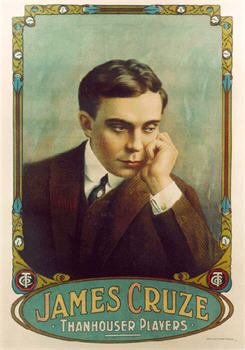

Starring: Marguerite Snow, James Cruze, Viola Alberti, William C. Cooper, Harry Benham

Screenplay: Theodore Marston, based upon the novel by H. Rider Haggard

Synopsis: Egypt, 350 B.C. Amenartes (Viola Alberti), the pharaoh’s daughter, tries to persuade Kallikrates (James Cruze), a priest of Isis with whom she is in love, to elope with her. The priest struggles against his passion for the girl, but finally succumbs to temptation. The two flee Egypt, travelling together for two years, until their boat lands upon a rocky shore of Africa. Unbeknownst to the pair, they have entered a realm ruled by a mysterious immortal woman known only as “She Who Must Be Obeyed” (Marguerite Snow) who, via her mystical powers, becomes aware of the travellers. Summoning up a vision of the two, ‘She’ gazes intently at Kallikrates, and conceives for him a desperate passion. ‘She’ sends her guards to bring the travellers to her presence. When they arrive, ‘She’ hurries excitedly towards Kallikrates, but he moves with deliberation to Amenartes’ side. Recovering herself, ‘She’ tells the visitors of a magical flame capable of bestowing eternal life upon those who bathe in it. After conferring, Kallikrates and Amenartes accept her offer to lead them to the flame, although at the last moment, Amenartes decides to leave her baby with a servant girl. When the three reach the flame, however, ‘She’ declares her love for Kallikrates. He rejects her, and the outraged ‘She’ strikes him dead. The distraught Amenartes reclaims her child and flees, swearing that her descendants will return to take vengeance upon ‘She’. ‘She’, meanwhile, preserves the dead body of her love, vowing to wait through eternity for his reincarnation… England, 1885 A.D. The orphaned Leo Vincey (James Cruze) becomes the ward of Horace Holly (William C. Cooper). Years later, on Leo’s twenty-fifth birthday, he comes into possession of family documents, including a letter from his parents, in which he is charged to travel to Africa, to find and destroy ‘She’…

Comments: After a couple of false starts as a novelist, in 1885 Henry Rider Haggard drew upon both his own experiences as an official in British colonial Africa, and the public’s ongoing fascination with various archaeological discoveries in Egypt and events such as the excavation of Troy, and published King Solomon’s Mines. This hugely popular novel was almost single-handedly responsible for the birth of the fantasy of the “lost world”, in which explorers, generally English, would stumble across ancient cultures somehow cut off from the rest of the world, discover fabulous treasures, make repeated hair’s-breadth escape from threats of death, and in most cases bring about the utter ruination of the civilisations that had been doing just fine for thousands of years before the arrival of the story’s “heroes”. Leave it to the British.

Haggard himself was swift to take advantage of his initial success, following King Solomon’s Mines with a sequel, Allan Quatermain, and with She, a tale of yet another lost world, its beautiful, immortal, evil queen, Ayesha, “She Who Must Be Obeyed”, and the English explorer whom Ayesha recognises as the reincarnation of her long-lost love.

The tale of She proved to hold an irresistible attraction for the embryonic motion picture industry, being filmed no less than eight times worldwide during the silent era, as well as being spoofed in 1915’s His Egyptian Affinity. It was first the basis for a short film made by Georges Méliès in 1899, La Colonne De Feu, which concentrated upon the visual possibilities of the eternal flame that sustains and ultimately destroys Ayesha. The first American version was made in 1908 by Edwin S. Porter for the Edison Company; sadly, this appears to be a lost film. The story was next tackled by the Thanhouser Company, and it is this production, released in December of 1911, that is the oldest surviving version of the tale.

Thanhouser was one of the most important production houses during the development of the cinema in America. Based in New Rochelle, New York, the company turned out over a thousand films in the period between its founding in 1909 and 1917, when it ceased operation. Between these bookends, the company’s original owners sold their interest in it to the Mutual Film Corporation, famous firstly for being the home of the Keystone Cops and Charlie Chaplin during this period, and secondly for in 1915 being on the receiving end of the Supreme Court ruling that declared film to be a business and not an art form, and therefore not protected by the First Amendment; a ruling not overturned until 1952.

(Today, Thanhouser Company Film Preservation, Inc., run by the grandson of the company’s founders, is even more important, being devoted to the acquisition and preservation of silent films.)

Although the film is not without its points, it is perhaps fair to say that She is more interesting than good. In this era of two-reel film-making, literary adaptations were of necessity superficial; yet there is a wide gulf between, for example, James Searle Dawley’s Frankenstein, which manages in a brisk quarter of an hour to hit upon most of the main headings of the tale it is telling, and this frequently confusing rendering of She. Perhaps an assumption was made that the audience was so very familiar with Haggard’s novel, there was no need to put much effort into narrative coherence.

At any event, the existing film gives the impression, rightly or wrongly, of having been rather carelessly cut down from a longer version. What remains is skeletal at best, and there is a bewildering arbitrariness about the material that was left in – such as the devotion of a title card, in a film that desperately needs every title card it can get to explain what is going on, to the cheerful announcement that Leo Vincey’s guardian, Horace Holly, is, For his ugliness known as ‘The Monster’ – an announcement, by the way, that is as untrue as it is unnecessary: Holly has a silly beard, granted, but this is supposed to be Victorian England!

Equally strange is that easily half of She’s running-time is devoted to its prologue. We open in Egypt, with the pharaoh’s daughter, Amenartes, successfully seducing her priest-lover, Kallikrates, away from his religious duties and persuading him to elope with her. The two run from the temple to a caravan that Amenartes, the confident little minx, has waiting; and as we watch them flee Egypt, we learn that these two are surprisingly progressive in their ideas: while he rides a camel, she walks.

Two years pass in the twinkling of a title card, and the couple and their retinue – and their baby – end up landing a boat upon the eastern coast of Africa, near a rock that we are assured is called “Negro’s Head”: a slightly unlikely name, it seems to me, for an African landmark of 348 B.C.

(In the novel the rock is referred to as being “like the head of an Ethiopian”; it is Horace Holly, in his role as narrator, who uses the term “negro’s head”.)

The arrival is sensed by the mysterious ‘She’, who uses a nifty device like a private cinema screen to observe Kallikrates and Amenartes, and instantly conceives a fatal passion for the former priest. When the travellers are brought into her chamber, ‘She’ behaves as if Amenartes didn’t exist, to the displeasure of both her visitors. Kallikrates and Amenartes recover their good humour, however, when, in the most casual way imaginable, ‘She’ offers them immortality. Thanks to the messy execution of this scene, you would be forgiven for thinking that ‘She’ does this as a kind of welcome gift for every casual visitor who happens to come her way, in lieu of a muffin basket, perhaps, or a nice selection of toiletries.

And “messy” barely begins to describe the construction of the next sequence where, if not for another helpful title card – ‘She’ strikes the Egyptian dead when he spurns her love – we would not have a clue what was going on. Instead, we cut from ‘She’ in the eternal flame to Amenartes fleeing in horror; neither the offer of love nor its spurning nor the striking dead is anywhere in evidence. We see ‘She’ kneeling mournfully over Kallikrates’ body, which she will subsequently preserve and keep in her chamber for the next twenty centuries, and then cut to the bereaved Amenartes, who dedicates her son – “or his descendants” – to the eventual destruction of ‘She’.

And as it turns out, it’s just as well that Amenartes included that “descendants” clause. The story here leaps over two thousand years, stops briefly to show us the orphaned child, Leo Vincey, becoming the ward of the reluctant Horace Holly, then lurches forward again to Leo’s twenty-fifth birthday, when instead of the horseless carriage he was probably hoping for, he gets orders from his dead parents to travel to Africa and avenge his exceedingly distant ancestor by killing ‘She’. Many have tried in past ages, and all have failed, the letter concludes encouragingly.

Remarkably, Leo seems to find nothing unreasonable about this peculiar family legacy, nor does he hesitate to set out as instructed. We can only assume that there was another page to his parents’ letter that we didn’t see, one adding something like, Otherwise, you don’t get one red cent. What we do see is what is referred to as “the chart”, which is meant to guide Leo to the territory of ‘She’. It is truly a remarkable document…

Well, what wonder that Leo and Horace are able to find their way to that same rocky shore that Kallikrates and Amenartes landed on, lo these many years ago? After all, they know it’s on the east coast of Africa… (And if that’s not enough, the film seems to imply that the travellers made their entire journey by row-boat!)

Watching on her Intruder-Cam (which appears to be the same one as some two thousand years earlier; you’d think she’d have widescreen and high-definition by this time), ‘She’ reacts in disbelief to the sight of her latest visitors, because Leo is, of course, the reincarnation of Kallikrates. And yes, I think that does mean that She is the origin of all those countless subsequent stories that found themselves unable to say “Egypt” without also saying “reincarnated love”.

Anyway, Leo starts behaving oddly here. We can only assume that upon being confronted by ‘She’, he suddenly “knows” that he is indeed the reincarnation of Kallikrates: in his reaction to her, he is torn between furious anger and an inability to look upon her once she removes her veil. Leo also shrinks away from the murderous purpose that brought him there in the first place, only for Horace to hold him to his mark. ‘She’, seeing Leo torn, declares her love for him and hands him a knife, offering herself up to the blade; but Leo cannot do it.

He and ‘She’ – if you’ll pardon the expression – then celebrate their love in an exceedingly creepy way: by torching the no longer required preserved body of Kallikrates, who is of course the exact double of Leo. And then ‘She’, Leo and Horace head for the eternal flame, where it all ends in tears. ‘She’ steps into the flame that has maintained her for countless centuries, but which this time, Causes her to shrivel up, grow suddenly old, and die. Why? Ya got me.

(To be fair, the novel itself is hardly clear on this point, although it spends some time in speculation.)

Leo and Horace recoil in horror from the withered thing in the flame, and Horace forcibly drags the stricken Leo away. A final title card informs us that, Safely back in England, Leo destroys all records of “SHE, the mysterious”, and it’s – The End.

An uneven and unsatisfactory work, then, is this version of She. Perhaps its main point of interest, particularly in contrast in the completely artificial and stage-bound Frankenstein, is that much of it was shot on location—although it cannot be said that those locations are either appropriate or attractive. Indeed, watching all of the cast members, but the flimsily robed Marguerite Snow in particular, struggling over the exceedingly rocky ground meant to represent the land of ‘She’, you really have to admire their dedication – and even more so when you consider that this footage was probably shot in November, and in the vicinity of New York: no-one here is very warmly clad.

Despite the fantasy aspects of the story, there is only one real attempt at a “special effect”, with the dissolution of ‘She’ in the flames. The flames themselves are animated, while what they leave behind is a tiny, imp-like thing that, we feel, is as effective as it is because we don’t get a very good look at it. Nor is She much of an actor’s film. Marguerite Snow, who would become over the next few years one of Thanhouser’s biggest stars, gets little to do here but gesture dramatically – although granted, she gets to do that a lot. Snow is veiled for much of the film, which, while thematically valid, seems an odd way for a studio to treat one of its most popular actresses.

James Cruze, an actor who would later become a director – making both the seminal western The Covered Wagon and The Great Gabbo, among other things – plays both Kallikrates and the adult Leo Vincey, but doesn’t make much of an impact. (Cruze and Snow were married two years after making She together, a marriage that would end unhappily almost a decade later.) George O. Nichols, who directed She, was a perfect example of the kind of do-it-all tradesman who flourished in the early days of the cinema, directing over one hundred films, and acting in over two hundred. If the evidence of She is anything to go by, it is likely that it was not so much Mr Nichols’ artistry that saw him employed so often, but rather his ability to get a film in the can with great rapidity and a minimum of exertion.

To be fair, the description of Holly as ‘the Monster’ is from the book. He’s apparently pretty deformed. In fact, Leo (who is impossibly handsome) and he are referred to as ‘Beauty and the Beast’.

The veiling of She is also from the book, since any man who sees her instantly falls in love with her. Poor Holly also does, even when he knows how evil She is. So they did follow the book in a couple points.

The book also skims over lots of details, as to what civilization made all those perfectly embalmed bodies, that the current savages light up as torches for festivals. And just what has She been doing all this time? Doesn’t She get bored?

LikeLike

Oh, yes, I know—but neither detail is relevant to this version, so why are they there? We don’t see ‘She’ with any other man; we barely see Holly at all!

‘She’ has Netflix streaming on that screen, I’m sure…

LikeLike

Pingback: Dr Jekyll And Mr Hyde (1912) | and you call yourself a scientist!?

Now now, you’re forgetting the humanitarian aspect of those expeditions. Why, without a rise in the price of shares in the British Xenoparatic Enterprise when the loot comes home, there would be widows and orphans starving!.Well, more of them.

LikeLike

But surely the trafficking of opium in China is sufficient to support the widows and orphans??

LikeLike

I have always been a little annoyed that of all the many lost worlds available in fiction, She and a closely related novel have been adapted so very often… A closely related novel, I say. Are you familiar with Pierre Benoît and his novel L’Atlantide (1919), which seems like a bit of a close imitation of She. I haven’t read the novel yet and am uncertain how good the translation I have might be but there is a movie based on it that I strongly recommend – https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0010969/?ref_=nm_flmg_wr_41 – from 1926, and known, for some reason, as Missing Husbands, it is a magnificent film. It is sort of a deconstruction of the massive sub-genre that is She, in its many iterations.

LikeLike

Yes, I believe SHE is in fact the origin of the “reincarnated love” storyline that was gender-flipped in THE MUMMY (and most, if not all, subsequent movies that used it).

LikeLike