“British Government!? I’ll wipe them and the whole accursed white race off the face of the earth!”

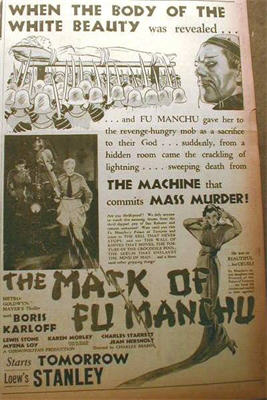

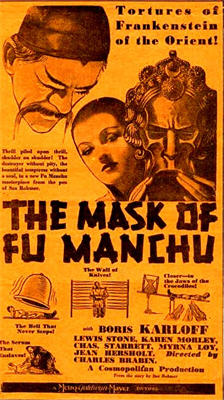

Director: Charles Brabin and Charles Vidor (uncredited)

Starring: Boris Karloff, Lewis Stone, Myrna Loy, Karen Morley, Charles Starrett, Jean Hersholt, Lawrence Grant, David Torrence

Screenplay: Irene Kuhn, Edgar Allan Woolf and John Willard, based upon the novel by Sax Rohmer (Arthur Henry Sarsfield Ward)

Synopsis: Sir Lionel Barton (Lawrence Grant) is called to the office of Commissioner Nayland Smith (Lewis Stone) of the British Secret Service, where he is astonished to learn that Smith is well aware of his proposed expedition to the edge of the Gobi Desert to seek the tomb of Genghis Kahn. Smith tells Barton that the golden mask and scimitar of Genghis Kahn are also being sought by Fu Manchu (Boris Karloff), who believes that with these artefacts in his hands, he can unite the Asian races in a war against the West. Only Barton getting to the tomb first can prevent such a catastrophe. Later, at the British Museum, Barton reveals his mission to his long-time friends and collaborators, Von Berg (Jean Hersholt) and McLeod (David Torrence), who immediately agree to accompany him. Unseen eyes are watching, however, and as Barton leaves he is set upon by three sinister figures… Days later, Sheila Barton (Karen Morley) and her fiancé, Terrence Granville (Charles Starrett), wait frantically for news of Sir Lionel. Smith must break it to Sheila that her father is the prisoner of Fu Manchu. When Sheila hears that Von Berg and McLeod intend to go ahead with the expedition anyway, Sheila insists upon going with them, arguing that her expert knowledge, gleaned from her father, will save days of searching. In his lair, Fu Manchu attempts to bribe from Sir Lionel the whereabouts of the secret tomb, first by the offer of money, then by the offer of his own daughter, Fah Lo See (Myrna Loy). When Sir Lionel rejects both with scorn, he is subjected to “The Torture Of The Bell”… Guided by Sheila, the expedition uncovers the entrance to Genghis Khan’s resting place. Von Berg, McLeod, Granville and Sheila lower themselves into the underground tomb, where they find the skeleton of Genghis Khan, wearing the legendary golden mask, and with the golden scimitar resting across its lap. As Terry removes these artefacts, the team’s Chinese workmen suddenly rush into the chamber, throwing themselves at the skeleton’s feet. The archaeologists disperse them by firing their guns into the air. Meanwhile, Fu Manchu gathers in his palace the leaders of all Asian nations. He summons Fah Lo See, who announces that the prophecy has been fulfilled: Genghis Khan has returned to lead Asia against the rest of the world… The archaeologists reach town to discover Nayland Smith waiting for them. He leads them into a deserted house, warning them not to turn on any lights. He also tells them that he knows that Fu Manchu is in the vicinity, and that it is imperative that the artefacts are shipped out of the country as soon as possible, so that they are in a position to negotiate for Sir Lionel. The artefacts are placed for the night in an attic room, and McLeod takes the first watch; but Fu Manchu’s minions are watching, and before long McLeod is dying, a knife in his back… The next day, Nayland Smith goes to make preparations for their departure, leaving Terry on guard. As he watches in the garden, a gruesome memento suddenly drops at Terry’s feet: a human hand, wearing a distinctive ring—Sir Lionel’s ring…

Comments: Following the tragic death of Lon Chaney in 1930, only weeks after the premiere of his first and last talking picture, The Unholy Three, his studio Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer shied away from producing any further exercises in the macabre, preferring to concentrate instead upon consolidating its reputation as the home of prestige motion pictures. However, despite the disapproving head-shaking of film critics and social commentators alike, by the middle of 1931 the movie-going public was showing no sign of losing its taste for “horror pictures”. After twelve months of looking on as Universal, RKO, Paramount and First National carved up this new marketplace amongst themselves, the executives at MGM decided that they, too, would have to enter the fray. By the end of the year they had two such films in production, and would ultimately release them on consecutive days in February of 1932. One of them was the studio’s be-careful-what-you-pray-for attempt to outdo the competition at one stroke with something “more horrible than all the rest” – namely, a little film called Freaks. The other was The Mask Of Fu Manchu.

MGM’s 1932 production was not the first time that Sax Rohmer’s xenophobic fantasies had been transferred to the screen. Dr Fu Manchu made his screen debut in Britain during the early twenties, in a string of silent “episodes” (released like a serial, but with each part more or less autonomous) starring Harry Agar Lyons. His Hollywood – and sound – debut followed in 1929-1931, with Warner Oland featuring in three productions at Paramount. Bizarrely, after starring as Fu Manchu, both the Irish Lyons and the Swedish Oland would ever afterwards be condemned to masquerading as “Asians”. Lyons’ short film career would play itself out in the form of Fu Manchu clone Dr Sin Fang, while Oland would, of course, go on to play Charlie Chan.

For their production, MGM chose to borrow from Universal one of the actors who had helped to put the horror film on the map. The release of Frankenstein at the end of 1931 had swift and dramatic consequences for Boris Karloff, who at the age of forty-four suddenly found himself the film industry’s most unlikely superstar. Karloff was, of course, irreversibly “typed” after Frankenstein, confined to spending the rest of his career as a “horror star”—although after so many struggling years as a bit player, he was grateful to be so. All the same, the three major roles that followed Karloff’s star-making turn could hardly have been more different from it or from each other. 1932 saw the actor top-billed as Morgan, the mute, sinister butler in James Whale’s The Old Dark House; as Im-Ho-Tep and his alter ego, Ardath Bey, in The Mummy; and as the titular criminal mastermind in The Mask Of Fu Manchu.

Although as unsubtle as the film itself, Karloff’s performance here is a real delight: his Fu Manchu simply oozes with unctuous malevolence. Thankfully not attempting any kind of accent – Fu Manchu was educated in the West, after all – the actor wrings the utmost from his exaggerated dialogue, leaving all of his co-stars, Myrna Loy excepted, floundering in their colourless and forgettable roles. Some of Karloff’s lines are, granted, more memorable for their content than for their delivery – more on that later – but you will never forget Fu Manchu’s modest introduction of himself to Sir Lionel Barton:

“I am a Doctor of Philosophy from Edinburgh. I am a Doctor of Law from Christ’s College. I am a Doctor of Medicine from Harvard. My friends, out of courtesy, call me ‘Doctor’.”

The Mask Of Fu Manchu is a typical MGM production, with a headlining star, a name supporting cast, and lavish production values. Indeed, the film is a feast for the eyes, from the elaborate costumes worn by stars Karloff and Loy, to the spectacular black-and-white cinematography of Gaetano “Tony” Gaudio, to the amazing set design provided by Cedric Gibbons and his crew. (And in terms of beautiful impracticalities, Fu Manchu’s cavernous yet minimalist operating theatre even manages outdo the art deco morgue of Warners’ Mystery Of The Wax Museum.) The film is also typical MGM inasmuch as its content is – using the term loosely – realistic. Circumstances may have forced MGM to dabble in the horror genre during the thirties, but in none of their productions did they ever venture into the truly fantastic, getting no closer than the explained-away supernatural doings of 1935’s Mark Of The Vampire.

Although this film is sometimes classified as science fiction, it is so only in the broadest possible sense, with Fu Manchu possessing both an electrical doo-hickey (consisting of several strung-together Van de Graaf generators) whose only purpose seems to be the detection of forged antiquities, and – need I say it? – a death ray. In a nice convergence of elements, Fu Manchu’s electrical gadgets were not only furnished by Kenneth Strickfaden, but the man himself doubled for Karloff in the scene where a fake sword of Genghis Khan, substituted by Nayland Smith for the real thing, is put to the test. Boris, quite understandably, was reluctant to get too close to the various machines and their dancing electrical arcs, but their creator had no such concern.

In the end, however, we can see that The Mask Of Fu Manchu is most properly considered a horror film. There is a tendency these days to think of “back then” as a more innocent time; but even a brief examination of the films of the pre-Production Code era should be enough to dispel that misguided notion. The few years between the coming of sound and the crackdown in censorship from 1934 onwards saw the release of numerous films featuring a quite staggering degree of cruelty and perversion. The Mask Of Fu Manchu falls squarely into this category. It is not, however, the behaviour of Fu Manchu himself that is so very shocking. After all, what kind of evil criminal mastermind would he be, if he didn’t torture an enemy or two? – although his tendency to stroke and caress his victims – and dress them in nappies! – is rather unnerving. Where The Mask Of Fu Manchu is likely to blindside modern audiences is in the explicit sexual sadism of Fu Manchu’s daughter, Fah Lo See.

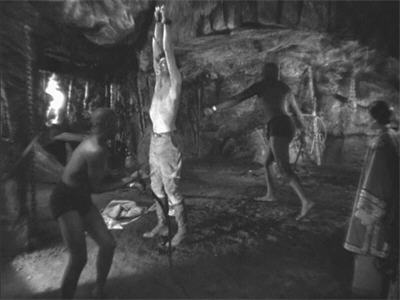

When Terry Granville unwisely ventures into Fu Manchu’s lair in an effort to buy the life of Sir Lionel Barton, he carries with him the golden scimitar that, unbeknownst to him, is a forgery. The deception revealed, Fu Manchu vents his rage upon Terry by—handing him over to his daughter. At Fah Lo See’s bidding, Terry is strung up, stripped to the waist, and whipped into unconsciousness, as the girl herself – crying, “Faster! Faster!” to the black slaves wielding the whips – watches in a state of undisguised sexual arousal. Having had her victim carried to her bedroom, Fah Lo See is about to have her wicked way with his bruised and beaten body when her father interrupts, having thought of a way to use Terry to get his hands on the real scimitar. “May I suggest a slight delay in your customary procedure?” Fu Manchu purrs at his daughter…leaving the mind boggling at the thought of how many times this scenario may have been enacted in the past.

(According to Hollywood legend, upon reading the screenplay the young Myrna Loy’s reaction to Fah Lo See’s excesses was the immortal exclamation, “Say—this is obscene!”)

Although structured very much like any of the numerous adventure films of the time, The Mask Of Fu Manchu separates itself from its fellows not so much in its violent content – many films of this era are amazingly violent – but in its willingness to put its heroes through the wringer. The torture of Sir Lionel Barton, which in story terms goes on for days, is dwelt upon in detail. (Never mind the film’s sexual content: The Mask Of Fu Manchu here sails perilously close to shattering one of the longest and most rigidly enforced of all cinematic taboos with its implication that during the torture of Sir Lionel, there won’t be any stops for bathroom breaks.) Towards the film’s climax, we also have simultaneous scenes in which Von Berg is strapped to a chair while two walls of spikes – “Silver Fingers” – close in upon him, and Nayland Smith is dangled over a pit of alligators. (Yup, alligators. In the Gobi desert. Props to Lewis Stone here, who does most of his own stunt work in this scene—even if it’s not him who subsequently tip-toes over the ’gators as Nayland Smith makes his escape.)

However, it is the scene in which Fu Manchu prepares and administers the drug that will turn Terry Granville into his unknowing tool that is my favourite.

(Which I guess means…my two favourite scenes in this film are the two in which Terry is tortured. Hmm. In my own, less demonstrative way, it seems I’m as bad as Fah Lo See.)

Strapped to an operating table by metal loops and clad only in a loin-cloth, the terrified, sweat-drenched Terry can only look on as Fu Manchu whips up a batch of a drug that he gloats is, “Better than hypnotism!” (Maybe; but on the evidence here, hypnotism is a lot less trouble.) The camera pans over three of the sources of Fu Manchu’s raw materials: a bowl of baby rattlesnakes, another containing tarantulas, and a third from which a gila monster is making an unhindered escape. Nevertheless, the good doctor turns to the containers built into the floor of his operating-theatre. A minion lifts the curved, hinged lid of one, revealing a jumble of snakes, spiders and lizards, and he selects from it a tarantula, extracting from it a quantity of venom approximately twice that of the spider’s body volume! He then crosses to a second container and lifts from it a very large boa constrictor, and proceeds to extract venom from that, too.

(Yes, you heard me. Well, I guess he never said he was a Doctor of Herpetology.)

The venom extraction is more complicated than you might imagine. Fu Manchu lets the snake bite one of his slaves on the arm, and as the man slowly dies, re-extracts the venom from his flesh and adds it to that of the tarantula. The two together are then added to a conical flask – which sits over a Bunsen burner, and already contains a Mysterious Coloured Fluid – and the final final result is pumped into Terry’s jugular. It is while under the influence of this drug that Terry betrays his comrades, leading them into a trap and turning over the mask and sword of Genghis Khan to Fu Manchu, before taking Fah Lo See in his arms, much to Sheila’s revulsion.

Apparently triumphant, Fu Manchu then reveals that as, “Genghis Khan come back to life”, he intends to lead the East against the West, and to wipe “the white race” from the face of the earth. As a first step, he intends to make “Christian martyrs” out of Von Berg, Smith and Sheila, with the latter a literal virgin sacrifice. Terry, meanwhile, having briefly snapped out of his drug-haze under Sheila’s influence, is hauled back to the lab for a second dose, which will make him Fah Lo See’s willing sex slave—“Until she tires of him,” as her father kindly explains to Sheila.

It is obvious throughout The Mask Of Fu Manchu that Boris Karloff was having a ball in the lead role (and he was not alone: notoriously, he and Myrna Loy disrupted shooting again and again with their giggling fits); and in the broadness of his performance, he certainly invites the viewer to join in the fun. The film’s opening scenes, too, seem to promise a certain amount of humour. “The British government is asking you to risk your life again,” Nayland Smith tells Sir Lionel Barton solemnly. “Oh, very well,” Sir Lionel responds with a casual shrug. There is also an hilarious bit when, upon leaving the museum after enlisting his colleagues for the expedition to the Gobi Desert, Sir Lionel is set upon and kidnapped by three of Fu Manchu’s underlings who are disguised as mummies…and who lie in wait for him, naturally enough, in sarcophagi. However, the light tone of these moments is misleading; and the film is, on the contrary, quite disturbingly straight-faced in much of what it proceeds to serve up.

Fu Manchu was, upon his first appearance in the literary world, described by his creator as “the Yellow Peril incarnate”. From this perspective, we can understand the significance of the fact, as is noted in the opening credits of the film, that The Mask Of Fu Manchu was a “Cosmopolitan Production”. Cosmopolitan was the film unit owned by William Randolph Hearst, which operated as a subsidiary of MGM. While it existed primarily to produce films starring Marion Davies, Cosmopolitan was also the voice of its owner’s various other interests and concerns. Hearst had been at the forefront of the “Yellow Peril” scare in America, using his newspapers to stir up racially-based fears and hatreds. It is not, therefore, particularly surprising to see a film like The Mask Of Fu Manchu, which plays the “Yellow Peril” card to the nth degree, emanating from that quarter.

If the violent and sexual content of The Mask Of Fu Manchu can make the modern viewer gasp in disbelief, its unrelenting and unapologetic racism is enough to make your hair stand on end. In this, the film is, in one sense, simply being true to its source—although in some respects, it exceeds even Sax Rohmer, who despite his nakedly anti-Asian sentiments always allowed for a certain grudging respect between the Chinese master criminal and his thoroughly British nemesis (who, curiously, has here misplaced his “Denis”, being addressed throughout just as “Nayland”). Here, there is no room for any such feeling. Even Fu Manchu’s extensive Western education is considered a mark against him—intelligence and education being, as is so often the case, explicitly correlated with evil.

In the film’s opening scene, Nayland Smith recruits Sir Lionel Barton to his cause by conjuring up a vision of a race war, should Fu Manchu find the mask and scimitar of Genghis Khan before they do. “He’ll lead hundreds of millions of men to sweep the world,” prophecies the Commissioner grimly—and you can understand his indignation: sweeping the world was, after all, England’s privilege. And indeed, this proves to be Fu Manchu’s intention—although by “world”, we soon learn, he means white world. The invective starts comparatively slowly, with Fu Manchu agreeing with Fah Lo See that Terry is, “Not entirely unhandsome, for a white man”; but before long he is threatening to, “Wipe the whole accursed white race off the face of the earth!”

Actually—being wiped out isn’t the fate that awaits the entire white race: for one half of it is reserved A Fate Worse Than Death. We have already been made aware of the “natural” physical superiority of the “white race”, in Fah Lo See’s instant attraction to Terry—although given the girl’s general conduct, we are also permitted to view this as one more aberration on her part. No, the specific threat here is against the white woman by the Asian man. The mask and scimitar of Genghis Khan secured, Nayland Smith’s first concern is to get Sheila out of the country. “Do you suppose for a moment that Fu Manchu doesn’t know we have a beautiful white girl here with us?” he demands of the suitably appalled Terry. Sure enough, when Sheila falls into Fu Manchu’s hands she ends up being exhibited to the howling, sword-waving mob as an incentive to action. Having proclaimed himself Genghis Khan incarnate, Fu Manchu rallies his “chieftains” by showing them the reward that awaits them once they have conquered their enemies: namely, white nookie.

Shimmeringly fair in her flowing white robes, Sheila is carried in by Fu Manchu’s black servants, while the gathered “Asians” stretch up their hands to paw at her. Finally, she is put on exhibition at the front of the room, while Fu Manchu looms over her.

“Would you all have maidens like this for your wives?” Fu Manchu cries to his followers. “Then conquer and breed! Kill the white man and take his women!”

(This pivotal moment is somewhat undercut by the over-enthusiasm of the extras playing the “Mongol chieftains” who, upon being asked if they want maidens like these, respond with a wholehearted shout of, “YEAH!!”)

Incredible as it may seem, the real offensiveness of The Mask Of Fu Manchu does not reside in its outrageous Asian stereotypes. Those at least were intentional. Where this film really disturbs is in what it does all unknowingly, which is to present us with a group of “heroes” who are not only in every respect as viciously bigoted as the bad guys, but utterly insensitive towards, utterly contemptuous of, every culture on earth but their own…and then expect us to sympathise with them.

No doubt, the Caucasian can hold his own when it comes to racial invective. As soon as Nayland Smith has mentioned Fu Manchu, we are hearing about “his wicked eyes” and “his bony, cruel hands”. So on it goes. It ultimately falls to Sheila Barton to address Fu Manchu to his face as, “You hideous yellow monster!”

The difference here is that while Fu Manchu’s insults are deliberate and calculated, the Europeans don’t seem to realise they’re doing anything wrong, or that others might find their choice of language and their behaviour deeply offensive. Upon opening the tomb of Genghis Khan – to whom Terry has earlier referred as “the jolly old skeleton” – the archaeologists stand for just a moment, awe-struck. “You’re standing in the unplundered tomb of a king who died over seven hundred years ago!” comments Von Berg to Sheila—and promptly plunders it.

When the Chinese workmen rush into the opened tomb to kneel before the remains of the Khan, the others are astonished and indignant – fancy, Chinese people having the temerity to enter a Mongolian tomb! – and chase them out by firing their guns into the air. (Yes, by firing their guns in an enclosed, underground tomb: wherever white superiority resides, it clearly isn’t above the neck.) Terry also finds it necessary to kick one or two of them up the backside.

Having blithely secured the treasures of another nation – objects sacred to their rightful owners, yet sneeringly considered as just one more curiosity for the British museum by our heroes (and with anyone objecting to their actions dismissed as “fanatics”) – the Englishmen become aware that – surprise! – they’re being watched. “We can’t even trust our own coolies!” laments Nayland Smith. Well, hey, Nayland: try not calling them “coolies”, and see where that gets you! The climax of this film sees the three remaining white men freeing themselves from their various predicaments. Terry goes to rescue Sheila (even her natural superiority doesn’t allow her to rescue herself), and cuts down Fu Manchu with the scimitar of Genghis Khan—oh, irony! Meanwhile, Nayland Smith and Von Berg have gotten their hands on Fu Manchu’s death ray, with which they unhesitatingly slaughter the gathered chieftains in the room below them to the very last man.

(Although not, we note, the very last woman: thanks to last-minute re-writes and indecisiveness, Fah Lo See’s fate remains a mystery.)

At this point, those chieftains haven’t so much as lifted a finger against our heroes, but that fact isn’t permitted to bear any weight. And granted, they were planning to be part of Fu Manchu’s army for the destruction of “the accursed white race”…although given what we see of “the white race” in this film, one is hardly inclined to blame them. In fact, by the end of The Mask Of Fu Manchu, the viewer is likely to feel that the “Asians” and the “Caucasians” are just as bad as one another…while, perhaps, conceding white superiority, at least in one respect. If there is a message to be found in The Mask Of Fu Manchu, it seems to be that when it comes to racial bigotry, grave-robbing and/or mass murder, no-one beats Whitey. No-one.

In spite of all this, The Mask Of Fu Manchu Award For Jaw-Dropping Racism finally goes to neither its Asians nor its Caucasians, but to Hollywood itself. Few Asian actors were permitted to be “stars” in the early days of the film industry; and even when the lead character in a story was Asian, he or she would almost invariably be played by a white actor in make-up. The Mask Of Fu Manchu, however, takes this convention to disturbing lengths. It gives us not just a made-up Boris Karloff, but a made-up Myrna Loy as well.

(Surely one of the film industry’s most bizarre career transformations was that of Ms Loy, who in the space of two years went from playing not just bad girls and other women, but evil Asians and Eurasians as well, to a long reign as Hollywood’s favourite wife, the woman who proved that marriage could be fun, and husbands and wives, best friends.)

The “Asian-isation” of Myrna Loy was probably to be expected. Where things get truly worrisome is in the supporting and bit parts. In the first place, The Mask Of Fu Manchu – possibly taking a cue from Sax Rohmer – uses the word “Asian” with awe-inspiring broadness. There is not the slightest hint that anyone connected with the film was aware of the multitude of peoples, cultures, religions and ways of life that collectively make up what we generally term “Asia”. On the contrary, the word “Asians” is used to lump everyone from Singapore to Istanbul, and from Chennai to Vladivostok, together into a single, indistinguishable, swarming mass; a collective consciousness.

The crowning insult comes in the crowd scenes, as we realise that the vast majority of these homogeneous “Asians” are also played by white actors, and that only one of the actual Asians gets dialogue—and believe me, we wish he hadn’t. Willie Fung pops up in the film’s brief coda, playing a properly comic, and properly servile, and properly uneducated, pidgin-English-speaking, inanely giggling ship’s steward: an Asian who knows his place.

But even this isn’t the worst of it. In this battle for supremacy between “Asian” and “Caucasian”, there is no acknowledgement that anyone else is even present in the world. There are black characters in The Mask Of Fu Manchu, however—sort of. Fu Manchu keeps a small army of black henchmen. For the most part they are nameless, faceless ciphers who are used primarily for set decoration, standing around in the background of the lab scenes, naked except for their loin-clothy nappy things (this Fu Manchu definitely has a fetish), and coming to the fore only as Fu Manchu’s muscle…or as Fu Manchu’s victims.

This is classic Hollywood hypocrisy. Fu Manchu’s casual disposal of his black servants once they have served their purpose is supposed to be evidence of how evil and ruthless he is—yet when our so-called heroes are just as casual in killing them, we are expected to applaud it (as indeed was the case in countless films of this era, with “natives” and “savages” slaughtered beyond number). In short, the Asian man may deserve extermination for his audacity in attempting to threaten the superiority of the Caucasian, but in this world the black man barely even exists, being reduced to nothing more than set-dressing at best, or disposable victim at worst.

It is hardly surprising that for many years, The Mask Of Fu Manchu was a difficult film to see—or to see intact. With changing attitudes came censorship, the removal of much of the material I have been discussing. In a wonderful example of the double standard, for a long time only the anti-white invective was removed, while the anti-Asian invective was left untouched. And despite what I have had to say in this review, I am entirely in favour of the restoration of this film, and its availability uncut.

A viewing of The Mask Of Fu Manchu today is a real right brain / left brain kind of experience: on one hand, if you manage to overlook the appalling racism, the film is outrageously entertaining, particularly in the wholly unexpected kinkiness of Myrna Loy’s performance; on the other, we must face up to this film as a documentary record of an ugly aspect of our collective past. Burying our heads in the sand, pretending that such aspects did not exist, achieves nothing…and we know what they say about those who forget history.

Such lessons are all the more important in a world where prejudice too often comes disguised as patriotism, and where both sides, all sides, of our various conflicts use the behaviour of the minority to excuse the transgressions of the majority against what they know to be right…and where attempts to stem the tide of such conduct are too often swept aside with jeering accusations of political correctness. (You say “political correctness”, I say “good manners”.) With this in mind, we should, perhaps, close by highlighting the one fleeting, fascinating moment in The Mask Of Fu Manchu when the film suddenly gives us a surprising glimpse of a broader awareness.

As he contemplates the scimitar of Genghis Khan, Nayland Smith shakes his head. “Will we ever understand these Eastern races?” he inquires sadly of his companions. “Will we ever learn anything?”

You, Nayland? Absolutely not. The rest of us? Well—let’s hope…

*******************************************************************************

“Say—this is obscene!” I can hear Nora Charles saying this.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes! You can hear Myrna saying that, which makes me pretty sure it’s a true story.

LikeLike

Warner Oland also played the “Japanese” scientist in WEREWOLF OF LONDON. What a strange career.

LikeLike

Well… It’s a livin’, as Bugs Bunny would say.

(Another film to copy over, you remind me.)

LikeLike

He also played Charlie Chan. IIRC, Oland pretty much built his career on playing Asians.

LikeLike

I read somewhere that Warner Oland had a Mongolian grandmother. He certainly didn’t look like your typical Swede.

LikeLike

I really need to pick up this movie and watch it. My first and still favorite encounter with Fu Manchu was the Brides of Fu Manchu, it had everything my young techi sci-fi heart loved. A cool mad scientist villain played just right (Christopher you will be so missed), a planet threatening death ray with lots of techy looking machinery and controls, a quasi-scientific basis for at all that worked for the audience, and yes the action, torture and mayhem. I think I’ve seen two others, both with Christopher Lee, one of which was the MST3K version of Castle of Fu Manchu.

LikeLike

Yes, you do! 🙂

I think I’ve seen all of the Lee Manchu films, though I must confess I have trouble keeping them straight in my mind. (I remember Castle best, and not just for MST3K—for Jess Franco + Rosalba Neri in drag: yowza!)

LikeLiked by 1 person

This must be a distinct influence on Flash Gordon too (what with the comic strip starting in 1934).

I can’t remember which of the Lee Fu Manchus it is, but I recall one where the “overload the reactor” lever is perfectly placed for a dying henchman to fall on it.

LikeLike

That’s Castle too!

LikeLike

****SPOILERS*****

That was Brides of Fu Manchu, my favorite. The ‘Death Ray’ in the movie is actually a broadcast power setup that would have made Tesla green with envy. A massive power plant feeding a transmitter system. The receiver would turn the energy into a sudden quick release of energy disintegrating everything around it. But there was a limit to how much the system could handle at the transmission site so they built an actual lever that had to be manually moved past a safety notch to feed in any more power than the safety limit. For a safety mechanism it was rather poorly designed, a simple safety catch would have prevented the disaster.

When the heroes jammed the signal, Fu Manchu told his daughter to move the lever a little past the safety mark and hold it to give them the little extra bit of power to break through the jamming. His technican though panicked and tried to stop her. Fu Manchu shot him and he fell onto the lever pushing it all the way down to the maximum position causing the system to overload and blow up..

Technology wise it really not a bad idea. Broadcast power is certainly a reality and achievable thing. But receiver/bomb is the real problem. The only way I see it working is if the power is being built up in some sort of capacitor that suddenly releases it when ready. But if you had that why do you need the transmitted power, just taps the local power mains and let it build up on its own. Still as death rays go it one of the better ones I’ve seen.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ah, you’re quite right! Too many damn levers in this subgenre! 😀

LikeLike