“Listen to what I have to say: as you seek this—creature—remember that you act in the name of mankind, and act humbly; for man is near to forfeiting his right to lead the world…”

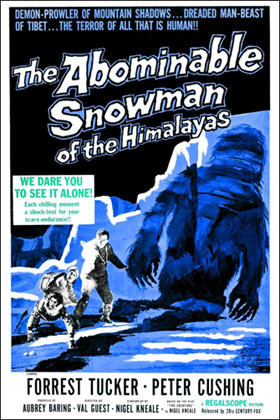

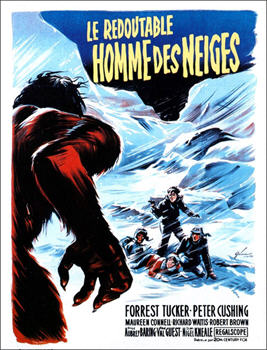

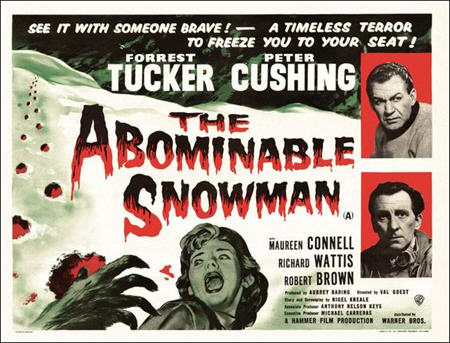

[aka The Abominable Snowman Of The Himalayas]

Director: Val Guest

Starring: Peter Cushing, Forrest Tucker, Maureen Connell, Arnold Marlé, Richard Wattis, Robert Brown, Michael Brill, Wolfe Morris

Screenplay: Nigel Kneale

Synopsis: English botanist Dr John Rollason (Peter Cushing), his wife and colleague, Helen (Maureen Connell), and their associate, Peter Fox (Richard Wattis), are studying medicinal plants high in the Himalayas, while staying in a monastery at the invitation of the Lhama (Arnold Marlé). One day, the Lhama leads Rollason through a conversation that touches upon his work, his marriage, his past experiences in the Himalayas—and the climbing party that Rollason is expecting. Rollason insists that he knows little of the other men, and tries to avoid the Lhama’s questions about their intentions. However, when Helen enters, both she and Rollason are shocked – though in different ways – when the Lhama mentions Rollason’s plan to join the other party on a climbing expedition: Rollason cannot understand how the Lhama could know this, while Helen is frightened for her husband’s safety, given that some years earlier he was seriously injured in a climbing accident. Left alone by the Lhama, the two confront one another. Rollason tries to explain that he saw no point in saying anything until he was sure the others would turn up, but Helen isn’t listening: she is remembering Rollason’s strange theories, developed after an earlier exploration of the Himalayas, and now understands why their “plant gathering” expedition was conducted so late in the season, so high in the mountains… That evening, Tom Friend (Forrest Tucker), his partner, the brash Ed Shelley (Robert Brown), and nervous Scotsman, Andrew McNee (Michael Brill), arrive as the Lhama predicted. Over dinner with the Rollasons and Fox, Friend and the others speak frankly of their intention to prove the existence of the creature known as the Yeti. Helen and Fox both reject the idea—only for McNee to speak quietly of the time he found a line of footprints in the snow, and felt the presence of…something… Friend produces the “special evidence” of which he previously wrote to Rollason, a silver reliquary covered with engraving, and concealing a huge canine tooth; Rollason translates the carving as, “The protection of the Powerful Beings is sought by the Lhama of Rongruk.” Friend explains that the artefact was stolen from the monastery some years earlier, as Helen examines the tooth and pronounces it to be “living ivory”. Friend argues that the reason previous expeditions failed to find the Yeti is that with their size and noise, they frightened the creatures away; he now plans for only the five of them – himself, Rollason, Shelley, McNee and a single guide, Kusang (Wolfe Morris) – to make the journey, relying upon supplies cached up in the mountains earlier in the year. He further explains that by leaving it this late, the snows will already have restricted the creatures’ movements to a few valleys. Over Helen’s continued protests, Friend urges Rollason to join them. Instead of answering, Rollason asks permission to show the reliquary to the Lhama. The Lhama identifies it, but then dashes the others’ excitement, first by explaining that inside is not a tooth, but an ivory carving, then by scoffing at the idea that there is such a creature as a Yeti. Nevertheless, Friend insists that he and his companions are going ahead, and that they will find the Yeti—and after a moment, Rollason too commits to the expedition. As the others leave, the Lhama calls Rollason back, warning him that if he is determined to seek the Yeti, he must do it with humility in his heart…

Comments: The Curse Of Frankenstein may have been the film that made Peter Cushing a star, but it was not his first foray into science fiction. That came two years earlier, towards the end of a remarkable body of television work that made Cushing a household name in Britain, when he became the public face of a one-two punch delivered by Nigel Kneale.

Late in 1954, Peter Cushing played Winston Smith in an adaptation of 1984, which had aired as part of the BBC Sunday Night Theatre program, and which was both hugely popular and hugely controversial—not least because (sign of the times) it had aired on a Sunday: such a grim and confronting story was considered inappropriate Sabbath material. Matters even went so far as questions raised in the House of Commons over the regulation (or lack thereof) of the television industry. Kneale then gained a couple of powerful advocates when Queen Elizabeth and Prince Philip made it known that they had watched and enjoyed the broadcast. But whatever the criticisms made at the time, posterity has had the final word: Nineteen Eighty-Four now sits comfortably on the BFI’s list of the “100 Greatest British Television Programmes”.

While the controversy was still playing out, Nigel Kneale, unmoved, reunited with his regular producer, Rudolph Cartier, and Peter Cushing to develop an original science-fiction production called The Creature. Stories about the Yeti, the so-called “Abominable Snowman”, were of ancient tradition in the Himalayas, and had been included in various explorers’ accounts of the 19th century, but first reached general public consciousness in the 1920s, when an Everest expedition led by Charles Howard-Bury discovered footprints which his Sherpas declared to be those of “The Wild Man Of The Snows”. As Himalayan exploration became more frequent, so did “sightings”: more photographs of footprints and various pieces of physical evidence were laid before a fascinated if sceptical public.

Interest in the Yeti peaked in the 1950s, when the question of the creature’s existence was taken seriously enough for the Daily Mail to mount the “Snowman Expedition”, specifically to look for evidence. Still more photographs, both of footprints and symbolic paintings of the Yeti from Buddhist monasteries, were brought back to Britain, and so was something the explorers claimed to be the scalp of a Yeti—analysis of which failed to determine the exact species from which the specimen was derived.

Such was the state of things when Nigel Kneale sat down to write The Creature—although typically, instead of penning a mere “monster movie”, Kneale used the Yeti as the basis for a rumination upon man’s place in the overall scheme of things.

Like Nineteen Eighty-Four, The Creature was planned as a complex, part-filmed, part-live production. The BBC gave Rudolph Cartier and his people both freedom and money, and they used it in the first instance to travel to the Swiss Alps, to get the necessary outdoor scenes in the can.

(Worried about safety issues, Cartier gave Peter Cushing the opportunity to be doubled in these scenes, but he insisted on participating. Hammer would later prove less accommodating.)

A few further inserts were filmed when the cast and crew returned, chiefly those involving guns or flares which were too dangerous to be done in the television studio. However, the bulk of the action was performed live for the cameras, with these sequences being integrated with the pre-shot material during the broadcast. As was standard at the time, the initial broadcast aired on a Sunday night, with a repeat broadcast on the following Thursday.

With the controversy over Nineteen Eighty-Four still hanging in the air, it is perhaps not surprising that reaction to The Creature was mixed. However, it is significant that while the media were largely critical or dismissive, the production was embraced by the public at large (many of whom found it a refreshing change from the drawing-room dramas that were the BBC’s stock-in-trade). Not everyone was willing to buy into the existence of the Yeti, but it was generally felt that Nigel Kneale’s philosophical approach helped to “put over” the more fanciful aspects of his story. Unsurprisingly, praise for Peter Cushing’s performance as scientist John Rollason was almost unanimous.

Sadly, these days we are unable to judge the merit or otherwise of The Creature for ourselves: unlike Nineteen Eighty-Four, the broadcast of The Creature was not recorded. What we do have, however, is The Abominable Snowman.

Even before the censorship watershed represented by The Curse Of Frankenstein, Hammer Studios had begun making waves earlier in the 1950s. In this respect, their most significant production was The Quatermass Xperiment, which signalled its intentions via the ‘X’ in its title: correctly anticipating the rating which would be slapped on the film by the BBFC in response to the production’s more gruesome material. Predictably, the critics were either dismissive or disgusted, but the film was a great success with the public: a reaction that encouraged Hammer to keep pushing the boundaries. The studio likewise continued to keep an eye on the activities of Nigel Kneale: The Quatermass Xperiment had originated as a six-part television series written by Kneale, which was broadcast to great acclaim in 1953.

Once more distinguishing between critical and popular success, Hammer bought Kneale’s screenplay for The Creature, hiring him to expand and adapt it for the big screen—interfering only so far as to alter the original title to the more exploitable “The Abominable Snowman” (which in the US was appended with the redundant “—Of The Himalayas”. As opposed to what? – The Abominable Snowman Of Fresno?). The only significant change made by Kneale himself was the inclusion of the characters of Helen Rollason and Peter Fox, in order to create greater tension around Rollason’s decision to join Tom Friend’s expedition. The film went into production early in 1957, by which time the Hammer executives were only too pleased to retain Peter Cushing in the role of John Rollason; Arnold Marlé and Wolfe Morris also reprised their roles. However, this time an actual American was cast as Tom Friend, with Forrest Tucker taking over the part which had been played on television by Stanley Baker (!).

The Abominable Snowman was released in October of 1957, four months after The Curse Of Frankenstein hit the fan, and offers an intriguing contrast. In place of the earlier film’s lurid colour, The Abominable Snowman was, like the earlier Hammer science-fiction productions, shot in black-and-white—and whether this was for budgetary or for mood reasons, the choice was exactly right. The greatest challenge in making this film was surely the integration of the location footage (this time shot in the Pyrenees) with the studio scenes. The results are almost seamless, something which could hardly have been achieved with colour cinematography. The main sets designed by Bernard Robinson – the Lhama’s room, the courtyard of the monastery and the visitors’ quarters – are also convincing. (They would later reappear in the Christopher Lee Fu Manchu films.)

However, the highlight of The Abominable Snowman is the presence of what we might call The Other Face Of Peter Cushing, who could hardly have found two better vehicles for demonstrating to the world his effortless versatility. Once again, Cushing plays a scientist—but in place of the arrogant, amoral Victor Frankenstein, we have the gentle, high-principled John Rollason, the film’s moral centre and its representative of mankind’s better nature: a role which Cushing essays with almost ridiculous ease.

The Abominable Snowman is a film of many strengths, but one, I think, that won’t appeal to everyone. For one thing, as “monster movies” go, perhaps only The Beast With A Million Eyes shows its monster less! – although here that was certainly a conscious artistic choice. Secondly, this is a rather talky film, with less action and more debate than might be anticipated from its exploitation-film title; while what action there is, is broken up by lengthy “slogging through the snow” sequences. Both of these aspects may try some people’s patience.

However, for those viewers able to take The Abominable Snowman on its own terms, the rewards are there to be had.

It is evident fairly quickly that there is something not quite right about the expedition made into Tibet by John and Helen Rollason and Peter Fox: they are there so late in the year that the plants they have supposedly come in search of are inaccessible. They are forced to rely instead upon dried specimens offered by the Lhama, part of the monastery’s medicinal stock. Helen in particular is worried about being late to meet their obligations to the Foundation which is paying for their work; yet Rollason seems in no hurry to wrap up their venture.

Nigel Kneale sketches both Rollason and Fox for us in a few economical touches. Rollason is the more broad-minded of the two, a real adventurer who embraces the challenges and difficulties of exploring, and revels in new lands and new people. For Fox, meanwhile, though he does what he must for his job, it is a case of gritting his teeth and getting through. The difference in attitude between the men is amusingly illustrated via their reaction to an offer of Tibetan tea (which, for those of you who don’t know, is made with salt and yak butter): Rollason has “learned to enjoy it”, while Fox almost tears himself in two trying to avoid the stuff while not being guilty of any rudeness to his host.

The third point of the visiting trio is one of this film’s most important touches. The character of Helen Rollason, as I have mentioned, is not in the original television version; and while it is not a major part, it is a very important one in context. The script makes a point of emphasising that John and Helen are real partners, colleagues as well as husband and wife, and that she is accustomed to roughing it with him for their work: one of the sweetest touches in this film is the way person after person expresses surprise at Helen’s presence, only for John, with an air of quiet bemusement, to respond that, well, of course she is with him…

(And then there is the detail of her being called “Helen”. Did Nigel Kneale put that in for Peter Cushing, I wonder?)

This delineation of the Rollasons’ relationship is vital in making the viewer understand that when Helen protests John’s intention of joining Tom Friend’s expedition, this is not female or wifely timidity, or dislike of him going off on his own, but an expression of valid fears.

Rollason still has his mind on the botanical specimens when the Lhama abruptly asks him about “the men who are coming”, men who passed by before, earlier in the year, without paying him the usual courtesy of a visit. Specifically, the Lhama wants to know what the expedition leader, a man called Tom Friend, is looking for—and why Rollason is helping such people. (After the event, we will realise that the Lhama already knows the answers to these questions—and is testing to see whether Rollason will lie to him. He won’t, but he is evasive.)

Helen’s arrival interrupts an awkward moment, but things swiftly get worse for Rollason, as the Lhama, with deliberation, tells Helen that she is welcome to stay at the monastery, “While your husband is on his climbing expedition”—and having dropped this bombshell, he withdraws.

His words have all the impact he anticipated: Helen is aghast, partly because of a serious accident John once suffered while climbing, after which he gave it up, but also because she now realises that certain strange theories of his, about what might be living in the most isolated valleys of the Himalayas, were no mere idle speculation; and that their expedition – so high in the mountains, so late in the year – was not really to search for rare plants at all…

Rollason tries to excuse himself to Helen, explaining that until Friend and the others showed up, there was no point in telling her he was thinking of going with them; but when pressed, he stands firm on his intention of going in search of “that creature”.

Tom Friend and his companions show up as predicted by the Lhama, and we are immediately given reason to worry, in the men’s attitude to the local people, their bullying manners, and their assumption of the worst about everyone.

While I can picture Stanley Baker projecting the unappealing character aspects of Tom Friend, the natural contrast that exists between Peter Cushing and Forrest Tucker – not just physically or in terms of their nationalities, but right down to their acting styles – immediately creates conflict at the heart of the story, even before the emergence of the opposing philosophies of Rollason and Friend. It’s an effective piece of joint casting—although that said, I resent right down to my finger-tips the fact that Forrest Tucker got billing.

Meanwhile, though the opening dose of ugly-Americanism is deliberately jolting in the wake of so much quiet Britishness, an amusing bit of balance offered here. Richard Wattis often worked with Val Guest, who allowed him to escape the upper-class-twit stereotype, and he offers a nice subdued performance as Peter Fox. The joke here, however, is that not so long ago we had Fox expressing exactly the same complaints about Tibet and its people as do Friend and Shelley—but when he hears his own words, albeit roughened up, issuing from the newcomers, his response is a frosty, “I find this country rather attractive.”

First speaking to Rollason – who now adds a cautionary note, “If I come” – Tom Friend insists that their expedition will be the one that succeeds. He is, however, unwise enough to speak the word “Yeti”; and however little English the Tibetans understand, they understand that. Kusang, Friend’s guide, stares at him in dismay, understanding for the first time the purpose of the expedition.

Over dinner, something of a confrontation occurs, with Helen and Fox holding hard to their scepticism, Andrew McNee, in a state of obvious nervous tension, speaking of his own experiences and discoveries, and Friend revealing that he hired Kusang not just for his skills, but because he has seen a Yeti.

Friend also produces the silver reliquary, which we learn was stolen from the monastery years earlier, and the evidence of the tooth. He follows up by outlining his belief, which coincides with Rollason’s own, that the Yeti may be found in certain isolated valleys, and that winter is the time to seek them, when they are forced down the mountains and into restricted territory in order to find food; and that a small party, which won’t frighten them off, is the way to search.

Friend further reveals that the previous summer, he and Shelley stashed food and supplies all the way up the trail, including oxygen at its highest points. He presses Rollason for an answer, insisting that the expedition needs him, “As a scientist and as a climber.” Helen, meanwhile, is appalled by the dangers inherent in such an undertaking, with such a small party. Rollason, caught between them, hesitates—then consults the Lhama.

A curiously winding conversation follows, in which the Lhama insists that the “tooth” is not real, merely a carving, and scoffs at the idea of facing such danger to search for, “An animal that doesn’t exist.” Both Friend and Rollason are taken aback; the former, who knows that the tooth is real (he had it sectioned), reiterates his intentions—and finally Rollason agrees to join his party.

The Lhama drops his mask when alone with Rollason, offering an ominous warning about his responsibility, his role as the representative of mankind—who seems to be doing his best to destroy himself, and may indeed be doomed…

The expedition prepares to depart, though Helen has one last shot at dissuading her husband. She trusts neither Friend nor Shelley, and says so forcibly; nor are her fears lessened by seeing Kusang in close consultation with the Lhama’s head servant, who is clearly giving him instructions…

Rollason stands firm, however, insisting that he must take this opportunity to put his theories to the test.

The slogging-through-the-snow portion of The Abominable Snowman now begins in earnest, relieved by some admittedly spectacular mountain scenery. The first intimation of trouble comes in the form of three men, who seem to be following the climbers at a distance. As the party moves out into the open, a shot is fired—though how close it gets, we cannot tell. A return of fire frightens the followers away. Rollason has gotten a good look at them through his binoculars, however, and views with suspicion Kusang’s insistent cries that they are bandits, bandits…

Fading day and weather closing in pose the next hazards, forcing the party to a dangerous short-cut which nearly ends in disaster for McNee, whose slow pace has already earned the ire of Friend and Shelley, and who regard him as disposable. To the sympathetic Rollason, McNee later reveals that since his experience two years earlier, he has been obsessed with the thought of seeing a Yeti, but given his general inexperience and his evident state of nervous tension, no responsible climbers would take him with them. He was finally allowed to join Friend’s expedition, however—in exchange for payment.

The five men make it safely to their first camp-stop, a hut in which supplies were cached; and there Friend pumps Rollason for his theories about the Yeti: where it lives, what it eats—and its relationship to man. Rollason speculates that the Yeti belongs to a third evolutionary branch, in addition to the two which gave rise to the great apes and to Homo sapiens; a case of “parallel development”. He further suggests that only a remnant of that third population now survives—and does so by adapting to an environment where little else can survive.

Rollason then proceeds to summarise what were indeed the prevailing ideas about the height, weight and body-structure of the Yeti: a dissertation which causes Friend and Shelley to nod at each other, and reveal what they’re really doing in the Himalayas: not merely proving the existence of a Yeti, but trying to catch one for exploitation. Shelley is here revealed as an expert trapper, who has tungsten-mesh nets and cages stashed amongst the other supplies.

Rollason is horrified, but Friend insists his motives are “honest”, even if they are commercial; he kept them quiet because he had a fair idea of how someone like Rollason would react, and he wanted his help. Their argument is interrupted, but later Friend invites Rollason outside for a smoke, and tries to make his case. He insists that the world is “hungry for knowledge”, knowledge that has to be presented in a new way: the old way, Rollason’s way, isn’t good enough in this new, fast era. He further posits that finding the Yeti may help mankind better understand himself. Rollason is deeply sceptical of Friend’s claims and shows it, but declines any further debate.

The next day, the party breaks in two. Friend, Shelley and Kusang go on ahead, while Rollason declares his intention of searching for plant specimens, partly for their own sake, partly to support his theory of a food source for the Yeti: he, after all (as he observes, not without a dash of quiet sarcasm), joined a scientific expedition.

The others gladly offload McNee onto him, leaving the two to make their own way up the steep ridge—where McNee puts his foot into a “Yeti-trap” hidden by Shelley. As he will later point out proudly – while protesting the damage done by Rollason in his efforts to free his injured companion – it’s his own design, meant to grip, not cut; but it does enough damage to put McNee out of action. Shelley further defends himself by claiming that his traps have already worked: they’ve caught a Yeti!

In fact, what they’ve caught is a langur, a monkey found all over the subcontinent, with one or two species living at high altitudes. It’s a common enough animal, one kept in zoos all over the world, as Rollason points out; yet Kusang insists this is the fabled Yeti: an assertion that prompts Rollason to dismiss his alleged expertise and to declare that Kusang doesn’t know anything about the Yeti; rather than concluding, as we might be inclined to, that Kusang knows everything about the Yeti…

At the next camp-site, while Rollason treats McNee’s injury, Shelley tries to tune the radio. Finally he finds the frequency on which weather forecasts are broadcast for the various climbing parties, and the men are dismayed to hear that a blizzard is predicted in their area within the next twenty-four hours. Friend and Shelley start making plans to get the monkey down the mountain on a sled. In the course of their discussion, Shelley indiscreetly utters the word “Francini”—thus alerting Rollason to the truth about Friend’s identity and his intentions. He now knows him as the man responsible for a scandalous hoax, in which mentally defective children were passed off as having been “raised by wolves”.

This revelation brings us to one of the most critical moments in The Abominable Snowman. Friend, at this point, is prepared to accept Kusang’s assertion—which is to say, while he wants the glory (and profit) that would come with proving the existence of the Yeti, he isn’t particular about what he brings down the mountain under that name, as long as it is something he can sell to the public. This being the case, there was an opportunity for Rollason to possibly cut the expedition short, now that he knows what Friend and Shelley are really after, by playing along with them—but he doesn’t try. Alternatively, he could have simply withdrawn and headed back down the mountain. But—he doesn’t.

This is the strength of Nigel Kneale as a writer, of course. John Rollason is the film’s hero, our identification figure—but he’s not perfect. Appalled as he is by the company in which he finds himself, he still feels the need to vindicate himself and his theories; he still puts finding the Yeti ahead of the consequences if they do find it.

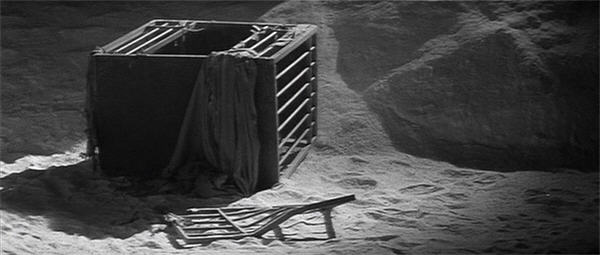

The most immediate consequence, however, is – surprise! – the smashing of the party’s radio, after Friend reacts violently to Rollason’s contemptuous condemnation of him as a “cheap carnival huckster”. (This from a man who has smuggling and gun-running in his past, in addition to the “Indian Wolf-Children”.) The two have barely calmed down when there are alarming noises from outside: growling sounds, cries from the monkey, something being ripped apart. They rush out to find the cage in tatters and the monkey gone. And in the snow nearby, there are gigantic footprints…

Friend’s first impulse is to send Kusang for the rifles (Rollason, perhaps in the shock of the moment, makes no protest). They are inside the tent, where McNee lies in a strange, trance-like state—emerging from it only when a huge, hairy hand reaches beneath the tent-flap, and begins inspecting the weapons…

Kusang arrives in time to see this. His cries of terror bring the others running. The creature is gone by the time they get there, and now it is Kusang who seems in a state of shock. He finally responds to Friend’s rough questioning, however:

Kusang: “I see…I see…what man must not see. I see…true…Yeti! You made me see it!”

With a cry of anguish, he breaks away and begins rushing down the mountain…

Friend finds Shelley’s trap in pieces; he brings the debris back to the tent where Rollason is worrying over McNee, who is again in a strange, trance-like condition—as he was when the Yeti first came close. Unguardedly, he speculates that McNee may be particularly sensitive to the creature’s presence, a hint which causes Friend to silently send Shelley – and his rifle – out into the night. Sure enough, one rifle-shot – and one cry of pain – later, there is blood on the snow. The men follow the trail and find what they have been looking for—or what two of them have been looking for: a Yeti, dead, with a bullet in it.

Don’t, however, expect at this point to get a clear look at it yourselves! The famous publicity shot of the dead Yeti bound on the sled is exactly that: no such shot appears in the film itself. Instead, we see only a single outflung arm, as the men comment of the creature’s height, and weight, and appearance; Rollason is greatly struck by its face…

This grim moment is interrupted by a series of eerie cries from the surrounding peaks. “They know,” says Rollason ominously.

(These simple scenes, with disembodied cries echoing across stark images of snow-capped mountains, are genuinely spooky.)

We’ve had occasional cutaways to the monastery, where Helen waits in fear, and we get another now, as Kusang stumbles into the courtyard, exhausted and terrified. He is quickly hustled away, but Helen knows what she saw and goes after him in spite of Fox’s protests. She gets lost within the winding corridors of the monastery, and is finally seized by the Lhama’s servant (the closest thing this film has to a traditional shock moment). When she comes to, she is in the care of the Lhama, who tries to persuade her that she is mistaken about Kusang. Helen stands her ground, insisting that the climbers are in danger, and that the Lhama must do something. He agrees to the first part of this, but not the second, saying calmly that John’s fate, all the men’s fates, are in their own hands, and will be determined by their own actions.

That’s not good enough for Helen, who begins making her own preparations to go after the others, recruiting the services of the porters who came with Friend, and who are still hanging around because they haven’t been paid. Unable to dissuade her, Fox resigns himself to going with her.

Meanwhile, Friend and Shelley have pronounced themselves dissatisfied with what Rollason derisively calls “the bag”, and are making plans to go on, further up the mountain, to where there is a cave with more equipment and supplies. McNee, having heard what happened, questions Rollason about the Yeti’s appearance—waving aside facts and figures and demanding to know about its face, where Rollason admits he saw gentleness; even wisdom.

As the men move the dead Yeti up to the cave, more cries are heard coming from the mountains. McNee – who, in an odd and creepy touch, moves his lips in concert with the cries – is compelled to follow the sounds, and sets out without gloves and wearing only a single boot. Discovering him missing, Friend and Rollason go after him, but are only in time to see his last, fatal plunge down the slope…

“They killed him,” Friend asserts bitterly. “Their cries drove him mad!” Rollason barely has time to point out that McNee’s left ankle wasn’t up to the strain of climbing before shots are fired back at their camp—where Shelley shows every sign of indeed being driven mad by fear. Two of them came at him, he gasps:

Shelley: “They’re after me! They know it was me!”

Friend doesn’t necessarily buy into this, but he knows an opportunity when he sees one. He has Shelley rig up his tungsten-wire net in the roof of the cave, where the dead Yeti now lies, and puts Shelley on guard nearby: live bait.

Shelley feels better having been given something to do, despite the nature of his assignment. So focused is he upon the task at hand, he doesn’t immediately understand why Rollason is asking for a spade…

The weather closes in as predicted, adding another complication to the situation: Friend is supposed to be keeping watch on the mouth of the cave from the tent, but as the blizzard builds, visibility drops. Inside, Rollason keeps up his efforts to talk Friend out of his current plan, equally afraid by this time for both the Yeti and for Shelley. His strictures about the Yeti’s place in the world, in history, inevitably fall upon deaf ears, but it turns out that he was right about Friend not being satisfied with “his bag”, the dead creature; he wants a live one, not just for the pay-off, but because he’s had a flash of something resembling conscience at the worst possible time: he wants to kill the shameful memories of the “Indian Wolf-Children”.

When the blizzard is at its height, there comes through it a growl and smashing sounds. Inside the cave, Shelley tries unavailingly to get his rifle to work, finally giving up with a despairing scream…

Hearing, Friend fires a warning shot into the air. By the time he and Rollason fight their way to the cave, the Yeti has gone, the net has been ripped to pieces—and Shelley is dead.

Rollason can find no signs of violence, and concludes that he died of shock; of fear. Puzzled over Shelley’s failure to fire his rifle, he evades Friend’s efforts to take it from him and examines it—and realises that it was loaded with dummy ammunition, so determined was Friend to capture a live specimen.

Rollason then discovers that the dead Yeti has been untied, though presumably the creature, or creatures, that had invaded the cave were scared off by Friend’s shot before they could finish their task. That was what they came for; not to hurt Shelley: “You did that,” says Rollason to Friend.

Having buried the expedition’s second victim, Rollason and Friend hunker down in the cave, where the latter starts making plans for their defence. He ignores Rollason’s speculation about the intelligence of the Yeti, the possibility even that the creatures have certain mental powers, insisting angrily that they are animals—and killer animals at that.

Rollason: “McNee died from an accident; Shelley died of his own fear. It isn’t what’s out there that’s dangerous, so much as what’s in us.”

So saying, he partially unwraps the dead Yeti to examine its face again, finding there again, as he thought the first time, gentleness. He then voices a startling alternative theory: suppose the Yeti are not a dying race at all, not a remnant hiding away, but rather are simply biding their time, waiting for Man to do what he does best: wreak destruction upon himself.

Rollason: “Perhaps we’re not Homo sapiens, thinking man – what has our thinking brought us to? – but Homo vastens, Man the Destroyer…”

He further speculates that the Yeti know exactly who and what Man is, what men are—including the two of them. If they can be dealt with, the secret of the Yeti is safe. They are the enemy…

Friend isn’t buying it, of course, and Rollason gives up. The two get themselves some dinner, in the midst of which Rollason has a curious experience: he hears a weather forecast, aimed as before at the “Tom Friend Expedition”, this one warning them to abandon all gear and return to base immediately. He goes hunting for the radio, and finds the only one they have—the broken one.

Rollason soon realises that Friend didn’t hear what he heard; but it isn’t much longer before Friend is hearing things: in his case, the voice of Ed Shelley, crying out for him, crying out for help—despite the fact that he lies in one of two graves on a nearby ridge.

Friend stopped Rollason plunging out of the cave in reaction to the “weather report”, but Rollason in turn is unable to stop Friend, who strikes him and knocks him down. Friend continues to follow the voice—past Shelley’s grave—shouting out in turn, and finally in increasing panic firing off his revolver—and so triggering an avalanche, which buries him alive…

When the ice-fall has stopped, Rollason struggles out of the cave and goes searching for Friend, though he must know it to be a futile quest. At last, exhausted, he drags himself back to the cave—

—where they are waiting in the shadows.

Rollason wavers to his feet, overwhelmed, staring up in awe and disbelief at the figures looming over him. One of them moves forward, and gazes back at him…

(We have here what I refuse to believe is anything other than a glorious in-joke. This is our only look at a Yeti’s face; Rollason, having examined and re-examined the dead one, speaks insistently of the “wisdom” and “gentleness” he sees there. He may well say so: with its high forehead, aquiline nose and soft eyes, the Yeti bears a distinct resemblance to Rollason himself—or, perhaps more correctly, to one P. Cushing…)

Meanwhile, somewhere down the mountain, Helen Rollason suddenly jerks awake—and like Andrew McNee before her, she plunges outside and up the slope without putting on extra gear, taking any equipment or waiting for anyone to accompany her. She is more fortunate than McNee, however, or perhaps is receiving guidance that he did not—because as she forces her way through the swirling snowstorm and scrambles upwards, she is suddenly face to face with her husband: half-frozen, in a state of shock, but—alive. Nearby in the snow, unseen by either the hysterical Helen or by Peter Fox, who finds her missing and follows her, are several gigantic footprints…

At the monastery, Rollason is nursed back to health, prior to taking his final leave of the Lhama. The Lhama speaks gravely of his terrible experiences, the loss of his friends in a series of accidents; and after all that, he did not even find what he was looking for.

“What I was looking for—does not exist,” responds Rollason after a moment.

“There – is – no – Yeti,” agrees the Lhama.

One of the most profound pleasures offered by The Abominable Snowman is its ambiguity. By the end of the film the viewer is certain that the Yeti does exist, but that’s about all we can be certain of. Various theories are proposed as to the nature of the creature, its origins, its way of life, its purpose; but theories they remain. We do not even know the nature of the relationship between the Yeti and the monks: who is protecting whom?

Meanwhile, all sorts of things are implied about the creatures’ mental powers, in which the monks, or at least the Lhama, are also implicated. Various references are made to “telepathy” and “thought transference”, which are inevitably classed by the visitors amongst the “native superstitions”, but we know that something else is going on.

Early on, the Lhama has fun jerking Rollason around, claiming that certain knowledge on his part is merely the result of his heightened senses, the consequence of the conditions under which he lives—before revealing things that he could not know this way, such as the approach of Tom Friend, or Rollason’s plans to join his expedition. But does the Lhama know this of his own powers, or is the information being “transmitted” to him?

Such incidents occur with increasing frequency. Rollason and Friend may not hear the voices in each other’s heads, but we do. Rollason even suggests that the Yeti came into the cave where Shelley was standing guard because they knew his gun couldn’t hurt them. The trance-like state into which McNee falls when the creatures come near is explicitly linked, via editing, to a deep trance in which the Lhama is found by Peter Fox. And there is no doubt that Helen’s sudden dash into the snow was the result of a mental warning, received unconsciously, but imperative.

But what of that ending?

This, too, is deeply ambiguous. Is it a pact of silence between Rollason and the Lhama that we are watching, or has Rollason been brainwashed to forget? We do not know—but disturbingly, the weight of evidence would seem to rest with the latter possibility. We recall in particular Kusang’s panicked assertion that man “must not see” the Yeti…

That Rollason alone is not only spared, but rescued, speaks for itself; yet it seems not unlikely that his conduct on the mountain was judged and found wanting. Perhaps his unacknowledged personal ambition damned him; or perhaps his mere passive resistance to Tom Friend’s schemes was considered not good enough.

The Abominable Snowman has been interpreted by some critics as a science-fiction reworking of James Hilton’s Lost Horizon, with its story of great knowledge hidden within the snowy fastness of the Himalayas, knowledge for which mankind at large is not ready—just the chosen few. Lost Horizon, however, ends on an optimistic note with respect to its questing hero; The Abominable Snowman, in contrast, strikes a pessimistic note typical of the 1950s. Mankind sent in its best available representative in John Rollason, and that representative was rejected. So much for the rest of us. Instead of a sharing of knowledge, The Abominable Snowman concludes with a keeping of secrets, and a tacit condemnation of Homo vastens.

.

Want a second opinion of The Abominable Snowman? Visit 1000 Misspent Hours – And Counting.

*******************************************************************************

This review is part of the B-Masters’ tribute to Peter Cushing.

what we might call The Other Face Of Peter Cushing

Indeed. I can’t think of another actor who has embodied both movie scientist archetypes – the amoral ego driven scientist and the wise compassionate humanistic scientist – as well and as seemingly effortlessly as Cushing. I’ve never seen The Abominable Snowman, I’ll have to check it out.

I really hope someone is planning to do Horror Express for their entry in this roundtable.

LikeLike

Boris Karloff could have done it, I think, given the material; as it is, his “good” scientists tend to be misguided and/or have things go horribly wrong. It is remarkable that Cushing should have been offered the opportunity, in consecutive films, to show his range like this—but yes, it is the absolute effortlessness that is so striking.

I really hope so too—which is to say, Someone has raised it as a possibility, but we’ll have to wait and see…

LikeLike

I fully get the vibe of AYCYAS and this might be off topic. But how often does one get to share their favorite poem with others who might not have had the opportunity to view it? This I first read in Bennett Cerf’s Houseful of Laughter and inspired me to track down and purchase the only book of poetry I own. And since it is about—–

THE YETI

F. Gwynplaine MacIntyre

Behold the bashful Yeti, the Himalayan Yeti:

Abominable Snowman in his mountaintop retreat.

The Yeti feels no passion for current vogue or fashion:

He sports no Gucci loafers on his size -eleven feet.

The Yeti always mutinies when faced with public scrutinies;

You’ll seldom see him in the pub and sipping ale.

Reporters from the London News

And television camera crews

(Who hope they’ll grant him interviews)

Inevitably fail.

Behold the bashful Yeti, the misanthropic Yeti:

Elusive and reclusive and a trifle shy is he.

Don’t send him invitations to social recreations;

He seldom comes to banquets, and he NEVER comes to tea!

The Yeti is so timid, he

Won’t come into proximity

Of since expeditions when they shout at him and wave.

The Yeti has no wish to stay

And chat with people such as they;

He’d really rather run away

And hide inside a cave.

So if you see a Yeti-a shy, retiring Yeti-

Just smile and keep on walking; that’s the proper thing to do.

Don’t call him names or tease him,

Or do things that displease him;

You really wouldn’t like it if a Yeti bothered YOU!

LikeLike

On the contrary! – my favourite poem is Lawrence Raab’s Attack Of The Crab Monsters 😀

So thank you for that!

LikeLike

Actually, I would be very interested in seeing “The Abominable Snowman of Fresno”.

Somewhat off-topic – The Backyardigans had an episode where the scientists try to find out the truth about the Yeti (One believes, one is skeptical, and one goes along for the ride). The believer says that the Yeti can be traced by his droppings, because his hands are furry and he drops a lot of things. In particular, raisins. And everyone knows that Fresno is the raisin capital of the world.

LikeLike

I can’t dispute *that* logic!

(Apropos, one party to the Himalayas did bring back some droppings containing a previously unidentified parasite…)

LikeLike

*Opens mouth to protest Ugly American stereotype*

*Looks at bronzer streaked mutant proboscis monkey squatting in White House*

*Hangs head, shuffles off*

LikeLike

Uh, yyyyyyyyyyyeah…

Sorry, hon: I think you’ve forfeited in perpetuity your right to protest!

LikeLike

*Dons frilly bonnet, hands out candy with apologetic smile*

LikeLike

Your review (I haven’t seen ‘The Abominable Snowman myself) brings to mind two other movies, one ridiculous, one sublime. The ridiculous one is ‘Boggy Creek II’, which not only shares the common trope of a group going out into the wilderness to find a creature for fame and science and getting its ass handed to it, but also the final conclusion that the monster is not a monster (we are the monsters) and needs to be left alone by man. I strongly suspect writer/producer/director/”star” Charles Pierce actually saw TAS and took a few things home in a take-away box for later.

The sublime one is ‘No Country for Old Men’. Before you roll your eyes – wait a second. Both of them use ‘being seen’ in an interesting, ambiguous way. TAS shows Kuang’s terror at seeing the snowman, and in the end, Cushing, the one person from the expedition to come back alive denies there ever was one, with the encouragement of the Lhama, who has to live with it. In ‘No Country for Old Men’, the only people left alive who run across Anton Chigurh are the ones who don’t “see” him (and the kids who help him after the accident). After Chigurh kills the man who hired him, Stephen Root, he turns around, and there’s a complete stranger standing there. The guy says, “Are you going to kill me?” Chigurh replies, “That depends. Do you see me?” My theory is that the strange, hallucinatory ending with Tommy Lee Jones is revealing that Jones saw Chigurh, too, in the motel room after Moss is killed – and pretended he didn’t, allowing him to get away but giving him nightmares and guilt for the rest of his life.

LikeLike

Many cultures have taboos that revolve around looking and seeing: it is another of this film’s ambiguities that we do not know the nature of the particular taboo that has Kusang in such a panic. (Nor, for that matter, do we know what happens to Kusang when he gets back to the monastery after having inadvertently violated it, but given the ending, we can guess.)

It wouldn’t be surprising to find TAS being remade in the American context, with Bigfoot instead of the Yeti: this set-up fits the “Who are the real savages?” scenario rather better than the Italian cannibal films that returned to that so obsessively!

LikeLike

What’s further interesting is that “looking and seeing” is one of the great dangers in Lovecraft’s stories. I’m certain TAS was made well before Lovecraft regained general popularity, but I wonder if the Yeti in the film aren’t meant to be slightly Lovecraftian.

LikeLike

I’m sure you’re tired of hearing this, but great review, hon! I’ll need to put this up near the top of The List as it sounds like it’d be up my alley. And not just because of our dear, sweet Peter.

LikeLike

Yeah, that just gets so tiresome. 🙂

I’ll be interested to hear what you make of it: I know some people really don’t like it, mostly in a Joseph Levene-esque, “Where’s the monster” sort of way.

LikeLike

Where’s the monster? Look in the mirror.

(Not you, Lyz, just in general)

LikeLike

Well, I just meant from me; I imagine it’s hard to judge if a piece is good when I compliment it, since that’s generally the case. In fairness, it’s not my fault; you’re the one with the delightful writing style. 😉

Oh dear…Lyz wants to know what I think of it. It just rocketed up The List. Better find it quick…

I will say that I am all about the monsters, but I don’t mind a lack of such if the rest is good.

LikeLike

Mz Lyz, thank you for this thorough examination. Until finding your post and Scott Ashlin’s, my entire knowledge of “The Abominable Snowman of the Himalayas” came from the page and a half that Bill Warren devoted to it in “Keep Watching The Skies!” The brevity of that entry made it clear that the late Mr. Warren had not been able to locate a print of the movie, as of his writing in 1987, though he dearly wished he could have.

LikeLike

You’re very welcome – thank you for dropping in! 🙂

LikeLike

Wow, this really makes me wanna see The Abominable Snowman now!

*sees the prices the DVD is going for*

Damn you.

LikeLike

Thank you.

Yes, I was lucky, I picked one up early.

LikeLike

another interesting Ugly-American side note – I just watched this this morning, and noticed that the expedition pronounces the guide’s name as Ku-Sang, with a long A. The llama pronounces it as Ku-Sahng, with a short A.

At one time, I worked with a man from India whose name was Rangnath, pronounced with short As. None of the Americans at work pronounced his name correctly, but used a long A for the first syllable. I tried to pronounce it correctly, and he appreciated it. A few years later, he sent out an email stating that he was going to go by Ron. It was probably the only way to get them to pronounce his name half-way correctly. I always felt sorry that he felt he had to do that.

I have a lot of trouble with people spelling my name when they hear it. I’ve had it spelled Don and Donna several times. Which is annoying, but not nearly as bad.

LikeLike

Wow. I think of “Dawn” as a very normal name- I’ve known plenty of Dawns. Now, my name… Ah, the many imaginative ways people have misspelled and/or mispronounced both my first name and my last name…

LikeLike

I used to think it was too, but the number of people who get it wrong would astound you.

LikeLike

I’ve been having all sorts of weird problems with WordPress sites recently- Here, I signed in with the name I usually use, here and elsewhere- my actual first name, Alaric- and somehow it comes out with a name I used to use for my email a couple of decades ago- I have no idea how it even got that name. And this was my second attempt to post- my first disappeared without a trace. Something similar happened on another site I follow recently, too. Both pages insisted that I needed to log in with my WordPress account- I didn’t know I even had one- and then acted really weird after I tried doping that. Both pages are ones I’ve replied on plenty of times before with no problems.

LikeLike