“A world that has never known the sun – or warmth – or light. We may even reach the lower depths—and see the people of the abyss!”

Director: Lucien Hubbard, Maurice Tourneur (uncredited), Benjamin Christensen (uncredited)

Starring: Lionel Barrymore, Lloyd Hughes, Jane Daly (Jacqueline Gadsden), Montagu Love, Harry Gribbon, Gibson Gowland, Snitz Edwards

Screenplay: Lucien Hubbard, based upon the works of Jules Verne

Synopsis: Count Andre Dakkar (Lionel Barrymore) and the Baron Falon (Montagu Love) meet on Dakkar’s island fortress, which lies off the coast of the country of Hetvia. Falon tells Dakkar that revolution is brewing in their homeland, and confides in him that at the end of it there will be a new king upon the throne: himself. Falon tries to recruit Dakkar to his cause, but the Count disclaims any interest in politics, insisting that he is a scientist only and wishes merely to be left in peace to do his work. At that moment, the volcanic currents beneath Dakkar’s island carry to the surface of the water a strangely shaped bone. Dakkar seizes it excitedly, telling Falon of his theory that in the depths of the ocean, another advanced and civilised race exists. He shows Falon the partially reconstructed skeleton of a being clearly not human. Falon is impressed, but points out to Dakkar that he will never be able to prove his claims. Dakkar then reveals his great secret: that he has designed and built a vessel capable of travelling beneath the sea. His mind on things far other than science, Falon inquires urgently whether the vessel is armed, and marvels at what a weapon it would make. Dakkar insists that the arms are defensive only, and swears that he will never allow his vessel to be used for any but peaceful purposes. Some time later, as Dakkar oversees the completion of the diving-vessel, workmen emerge from it in a state of alarm. The head engineer, Nikolai Roget (Lloyd Hughes), carries the vessel’s compressed air manifold, which was dropped by one of the men. Knowing that any damage to the manifold would mean that the vessel could never rise from beneath the sea, Nikolai puts it through a series of tests. As he does so, he is joined by Count Dakkar’s sister, Sonia (Jacqueline Gadsden), who is deeply interested in the work that Nikolai is doing—and still more deeply interested in Nikolai himself. Nikolai pronounces the manifold undamaged, and the diving-vessel ready for launching. Dakkar orders the launch delayed until Falon, who has expressed an interest in observing, can return to the island. As Falon arrives, he catches a glimpse of Sonia through a window. Eagerly, he hurries in to her—and is horrified to find her in Nikolai’s arms. Abusing Nikolai as an upstart, and threatening him with a horsewhipping for his audacity, the jealous Falon denounces the mortified young engineer to Dakkar, who soothes his angry friend by promising to speak severely to Nikolai…but who instead waits only until Falon and Sonia are out of earshot to assure his right-hand man of his approval. The imminent launch of the diving-vessel, however, overrides all other considerations. Dakkar’s workmen assure him that everything is in readiness, but Falon urges him to carry out one more test. Growing suspicious of the Baron, Nikolai pleads with Dakkar to allow him to pilot the vessel on its first short trip, arguing that if something does go wrong, in this way he, Dakkar, will survive to make another attempt. Dakkar finally agrees, telling Nikolai that his doing so is a measure of his trust in him. As Dakkar, Sonia and the workmen look on in wonder and pride, Nikolai pilots the vessel into the waters around the island. But even as those gathered celebrate, a troop of armed Hussars is secretly admitted to Dakkar’s city. A violent confrontation follows, and the anguished Dakkar must confront the knowledge that the man he considered his friend has utterly betrayed him…

Comments: With 1929’s The Mysterious Island, science fiction cinema moved into the sound era…after a fashion. Although over the preceding decade numerous European directors had eagerly embraced both the visual and the thematic possibilities of the fantastique, most American film-makers remained reluctant to follow their lead, confining most of their efforts to tentative productions full of spies, secret weapons and a lot of running around; action films masquerading as science fiction, a phenomenon still depressingly common today.

It took the overwhelming success of First National’s 1925 release of The Lost World to convince the other Hollywood studios that there was indeed a market for straight-up, homegrown fantasy. MGM, never known for doing things by halves, planned a spectacular that would outdo even The Lost World: their fantasy film would be a three-hour epic shot in two-tone Technicolor, full of adventure and romance and the kinds of special effects that had thrilled audiences just the year before. In the early days of 1926, MGM assembled a solid cast, led by Lionel Barrymore and including Lloyd Hughes from The Lost World, and divided the responsibility for their mammoth undertaking between Maurice Tourneur, who would direct the studio scenes, and pioneering underwater film-maker J. Ernest Williamson, who had guided the photography and special effects of Universal’s 20,000 Leagues Under The Sea eight years before (and had worked with Tourneur previously, on The White Heather). With high hopes and a million-dollar budget, The Mysterious Island went into production. And then disaster, both artistic and temporal, struck.

The first difficulty to trouble the production of The Mysterious Island was one caused by something which continues to afflict Hollywood to this day: the simple failure to think things through. In the mid-1920s, science fiction still suffered from a fairly dubious reputation; and in launching their epic, MGM had taken the precaution of following another of First National’s leads, and choosing to adapt an author who was both well-known and – perhaps more importantly – “respectable”. The selection of Jules Verne as a source, however, presented the production team with a quandary: whether to film Verne as written, or to update his story to a contemporary setting.

The wrangling over this point dragged on for month after month, and through re-write after re-write. Meanwhile, J. Ernest Williamson sat twiddling his thumbs and watching the ideal time of the year for his photography, which was to be carried out in the Bahamas due to the clarity of the light and the water, slip inexorably away. By the time Williamson was finally given the to all-clear start shooting, it was July: hurricane season.

Although his legacy is sadly little known today, in the early decades of last century J. Ernest Williamson was famous as one-half of the Submarine Film Corporation. Along with his brother, George, Williamson adapted an invention of his sea-faring father, a tube-like apparatus attached to a diving bell that could be lowered from a ship for salvage work and the like, into a facility allowing underwater photography. In the years that followed, Williamson’s “photosphere”, as it was dubbed, played a vital role in numerous motion pictures, both fictional and documentary—and should have done in The Mysterious Island.

Williamson’s portion of the production, however, was hit by not one, but three hurricanes: his equipment was ruined and had to be re-built, costing both time and money. Williamson soldiered on despite this adversity – continued to do so even when presented at length with a new version of the script, vastly different from the one he had been shooting from – and at last received the classic Hollywood reward for his heroic efforts: next to none of his footage used in a film that bore no resemblance whatsoever to the one he had agreed to shoot.

Meanwhile, the time being lost in the Bahamas was nothing compared to that being lost in Hollywood, where Maurice Tourneur’s slow and exacting methods – and his disinclination to pay any attention to the head office – finally brought the wrath of Irving Thalberg down upon him. Whether he jumped or whether he was pushed remains unclear, but in either event Tourneur departed the production in the latter part of 1926—and, disillusioned, never made another American film.

Tourneur’s replacement was another European expatriate, the recently arrived Danish actor / director Benjamin Christensen (who is best known today, and rightly, for the extraordinary Häxan). Unfortunately for Thalberg, however, Christensen and Tourneur proved to be kindred spirits: time limped on, and production costs soared, and still The Mysterious Island was no nearer completion; and so Benjamin Christensen went the way of Maurice Tourneur. The Mysterious Island’s third, last, and ultimately credited director was Lucien Hubbard, writer, producer and – by this time, more importantly – MGM company boy.

It is also Hubbard who is credited with the film’s screenplay, a mish-mash of Verne that owes a great deal to 20,000 Leagues Under The Sea, something to the twin tales of Robur The Conqueror and Master Of The World, a little, with its vaguely Russian-esque characters and its revolutionary background, to Michel Strogoff, and – in an early example of yet another proud Hollywood tradition followed to this day – nothing but its title to the text whose name it actually bears. Under Hubbard, The Mysterious Island was finally brought to completion—or so it initially seemed. Once again, external events overtook the endlessly troubled production.

The year that The Mysterious Island went into production, 1926, also saw the release of The Jazz Singer—and the rest, as they say, is history. By 1928, Hollywood was nervous and uncertain. The cinema operators, faced with the costs of total refurbishment, emphatically did not want sound pictures; the paying public, still more emphatically, did. The Hollywood films of the late twenties are a curious mixture. These years saw the release of works that are at the absolute pinnacle of the silent film-maker’s art—F.W. Murnau’s Sunrise and King Vidor’s The Crowd, for instance, to cite only two of the more obvious examples. At the same time, there were a few – a very few, granted – productions that demonstrated that their directors had already grasped the full potential of sound, such as Ernst Lubitsch’s remarkably accomplished version of The Love Parade. Between these two extremes lie the many more films that simply hedged their bets and included a sound sequence or two as a sop to the public, as the studios waited to see which way the penny would finally drop.

Hollywood’s first all-talking features were released in 1928, and by 1929 the way of the future was clear—and in the wholly silent The Mysterious Island, MGM had a hugely expensive white elephant on its hands. The decision was then made to go the way of the sound insert; to re-shoot the opening fifteen minutes of the film (which clocks in at 95 minutes, far short of the conceived three-hour running-time) with sound, as well as including a couple of other short dialogue sequences and numerous sound effects. This decision necessitated – or so the studio believed – the replacement of the accented Warner Oland, the original Baron Falon; all his scenes were re-filmed with Montagu Love, at the cost of still more time and still more money. Finally, in October of 1929, three years late and three million dollars over budget, The Mysterious Island was released to a rapturous critical reception—and to the utter indifference of the public. The film was a financial disaster.

Looking at The Mysterious Island today, it is difficult to comprehend what the audiences of 1929 didn’t see in it. Whatever its flaws, the film is a rousing adventure story, full of incident and imaginative sequences, and cleverly and intelligently designed; in its original colour format, it must have been a real eyeful. (Sadly, only black and white prints seem to exist today.) Perhaps, however, the distance between ourselves and the film’s first audiences is simply too great for us to see the film as they saw it; perhaps what we regard today as charmingly anachronistic seemed rather, to viewers in the late twenties, embarrassingly dated.

Then, too, there is evidence that once sound did begin to take over the American cinema, there was a strong demand for films that were absolutely contemporary, absolutely realistic, filled with people who lived and talked like the audiences watching them—or at least, as they would have liked to live and talk. Unfortunately for the producers of The Mysterious Island, all that early wrangling had at length concluded in a decision to go with a Verne fantasy world; to set the story in the fictional country of “Hetvia”, and in an indeterminate period of history; and to treat Count Dakkar’s invention of the “diving-vessel” as something entirely new and wonderful.

The film’s sound sequences are another matter again. The opening section of the film is awkwardly executed, certainly, but this probably grates upon the modern viewer far more than it did people in 1929. All of the problems inherent in the conversion to sound are evident in the exchanges between Lionel Barrymore and Montagu Love: the two of them are forced to deliver their lines while huddled together in the vicinity of the microphone. (Occasionally, one or the other forgets himself, and wanders a little too far away; the dialogue immediately drops out.) Meanwhile, although they are speaking out loud to one another, the two keep the broadness of gesture and expression that was common in the silent film. The extreme twitchiness of Lionel Barrymore throughout this sequence – leave your hair alone, Lionel! – is a clear indication of how uncomfortable even an experienced actor could be with the task of coping during this difficult transitional period. Watching, one can only sympathise—and reflect on the many whose careers failed to survive the transition…

The remaining use of sound in The Mysterious Island is more imaginative. Audiences today may not be so impressed with Count Dakkar’s diving-vessel, but his invention of a radio system that allows verbal communication between the land and the crew of the submersible is still a pleasing touch. The radio stars in two different scenes. The first is merely a demonstration of its function (with the consequent jarring revelation of Lloyd Hughes’s broad American accent; what is it about British accents, that makes them so much more acceptable in a fantasy context?), but the second is a far more dramatically imperative moment when the treacherous Falon forces an unfortunate captive to imitate Sonia’s voice, in order to lure Dakkar and Nikolai and their diving-vessel back to the surface. Additionally, the film features the use of various sound effects – metallic clanging noises in Dakkar’s shipyards, explosions during the various battles, clamorous voices in the crowd scenes – that are neatly integrated.

The most memorable aspect of The Mysterious Island, however, is not these “innovations”, but the extended underwater adventures of the central characters. The screenplay contrives to get everyone, good guys and bad guys alike, down into the depths of the ocean in Dakkar’s two submarines. There, Dakkar’s most outlandish theories regarding the co-evolution of an intelligent humanoid race beneath the sea are vindicated—although as it turns out, perhaps “humanoid” isn’t quite the right word to use.

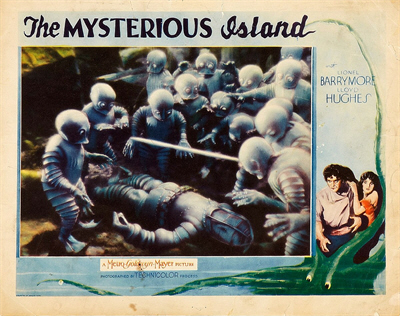

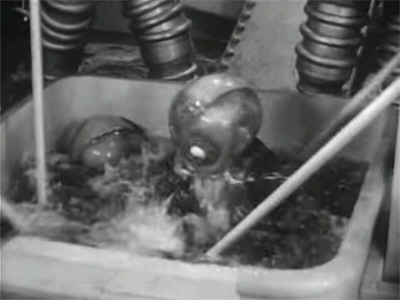

In the years before prints of The Mysterious Island were available (and they are far from readily available even now), all that most people knew of it, on the evidence of a series of tantalising stills, was that the film featured some of the oddest creatures ever to grace the screen. These “sea-people”, as they are simply dubbed, are indeed bizarre: pint-sized, duck-billed, web-footed, boggle-eyed and bulbous-headed, they are utterly, utterly adorable…so it will probably come as a shock to the uninitiated viewer, as indeed it did to this one, that they are frankly and instantly hostile! – their first action being, in a clever touch, to attack the diving-vessel that bears Andre Dakkar and Nikolai Roget with the battering ram from a sunken Roman galley!

(In the deceptive innocence of their appearance, the sea-people are rather like the little rock-dwellers in Galaxy Quest—or, for that matter, like any native Australian animal that you might care to name: they only look cute.)

This section of The Mysterious Island is notable for the extravagance of its execution—and for the amazing multitude of sea-people that swarms against the human characters. (Somewhere in that crowd is Angelo Rossitto.) They pose a serious threat not because of any actual violence they can commit as individuals, but simply through the sheer weight of their numbers.

But the sea-people are not the only marvels that Count Dakkar and Nikolai encounter on their way to the bottom of the sea—a journey, I should point out, made entirely involuntarily: their vessel has been irretrievably damaged by a barrage from Falon’s forces, and is sinking to its seemingly inevitable doom.

(This situation allows Dakkar to produce an absolutely hysterical piece of what I like to call “scientific consolation”: granted, he says to Nikolai, in a few hours the two of them are going to stifle to death in agony; but until then they will be in, “A world that no human being has ever seen before. We may even see the people of the abyss!” Nikolai, to his credit, seems rather more consoled than I suspect I would be in similar circumstances, good scientist though I like to think myself…)

On the way down, the vessel encounters a huge, hairy, spidery creature that simply hangs in the water; while our heroes later win a reprieve from the attacks of the sea-people when they themselves are attacked by “an ancient gluttonous enemy” – and lordy, lordy! – if it isn’t one of the screen’s earliest examples of a crocodilian masquerading as a dinosaur! This faux-finned beastie skitters all over the sea-people’s underwater city, as the residents flee in terror; and Dakkar and Nikolai buy themselves into the temporary favour of their reluctant hosts by disposing of the creature with their vessel’s torpedoes.

The death of the “dinosaur” is rendered by a still-frame, so I am left with the hope, as I am certainly not in some productions, that the poor animal wasn’t actually injured. The other notable thing here is that the makeup job on the gator, devised in 1928, is the best I’ve ever seen. How sad is that?

(Early on, Falon challenges Dakkar’s theory about the sea-people by demanding to known how anything humanoid could breathe down there? “How do fish breathe?” Dakkar shoots back at him—which is all very well, but it hardly explains what something that very obviously has lungs is doing down there!)

But as is so often the case, it isn’t long before the human beings – who by this stage of the film include Sonia, Falon, and a few of Falon’s men – wear out their welcome; and the sea-people retaliate by siccing on them an animal that they keep as a kind of pet: a giant octopus. Naturally. I mean, what underwater adventure would be complete without a cephalopod on the rampage?

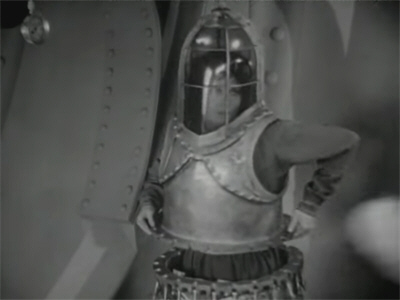

Although conceived and executed primarily as an adventure film, The Mysterious Island is not merely eye-candy. Though, indeed, the sets and underwater scenes are visually arresting, some real thought went into the design of the submarines, which are full of equipment that varies between the Fritz-Lang-esque and the unexpectedly practical-looking, and which must be operated by a trained crew via a proper chain of command. It is, however, on the level of character that this film is most consistently interesting. Admittedly, the Baron Falon is a purely cardboard cut-out villain, and Nikolai never comes across as anything other than your standard issue romantic hero; but in the Dakkars, Andre and Sonia, The Mysterious Island shows real imagination—and a touch of courage.

The fact is—I owe Sonia Dakkar an apology. The first time I watched The Mysterious Island, at the moment of Sonia’s introduction I flinched, gritted my teeth, and prepared to spend the next ninety minutes in a state of annoyance. Well, perhaps I was not so very much to blame: Sonia gets the worst kind of “heroine” introduction, all soft focus and fluttery eyelashes and twee romantic music; so you can imagine my delight when she turned out to be, not the useless, constantly swooning object that I was expecting, but a resourceful and courageous young woman; and far more enterprising a heroine than most of her immediate sound era descendants, who almost without exception play the role of passive victim.

(Notice, however, how all the advertising art has her either clinging to Nikolai, or cowering behind him. Old clichés die hard.)

The early scenes involving Sonia are rather misleading. Her constant visits to the engineering workshop have an ulterior motive that everyone – except, perhaps, that motive himself – is aware of; but it soon becomes clear that Sonia is an intelligent girl with a real and passionate interest in the work to which her brother and Nikolai are devoted. She is, moreover, brave enough to be unashamedly in love with a man who, no matter how deserving, is technically her social inferior – more on that subject later on – and, when he is hesitant to take the first step, to act upon her feelings. It is, indeed, Sonia’s love for Nikolai that propels her into danger; into worse than danger.

When Falon, in love with Sonia himself, discovers her feelings for Nikolai, he is both insanely jealous and socially outraged. When his forces have overrun Mysterious Island, Falon’s first action is to take Sonia prisoner. He does not know that Andre has placed the plans and documents describing the design of the diving-vessels in Sonia’s keeping; nor that when the invasion began, she hid all the papers—and is consequently the only one who knows their whereabouts. Falon tries to torture this information out of Andre – who of course cannot speak if he would – then orders the torture of Sonia, hoping by these means to torment Andre into speaking. He carries out this threat, too, when in order to save her brother, Sonia reveals that she, and only she, has the information that Falon wants. She stands up to the brutal treatment, however; although in the end, only a deep faint saves her from death.

But Sonia’s sufferings have only just begun. Andre is rescued by Nikolai, but the two men are drawn back into danger by Falon’s ruse of a false radio call from Sonia. As the diving-vessel surfaces near the supposed rendezvous point, the men see Sonia waiting as planned—but are unable, in the darkness, to see that the poor girl has been gagged and staked out like a Judas goat. (It is clear that Falon’s treatment of Sonia is largely motivated by his desire to punish her for loving Nikolai.) Helpless, Sonia can only look on in horror as the diving-vessel is shelled and seriously damaged. Subsequently rescued by one of her brother’s loyal workmen, Sonia eventually finds herself on the second diving-vessel, trapped with Falon and his men after a failed attempt by Dakkar’s men to reclaim the submersible.

The sequence of Sonia’s rescue and re-capturing has some fascinating touches. When Dmitry, the head of the workmen, succeeds in making his way out onto the rocky platform to rescue Sonia, he addresses her not as “Countess” or “my lady”, but simply as “Sonia”: it’s not the time or the place for any silly social conventions. What’s more, Dmitry’s rescue of Sonia is not as straightforward a business as it first seems. Dmitry has made a desperate resolution to try and reclaim the second vessel and, with Andre and Nikolai out of the way, he can only do it with Sonia’s expertise and assistance.

Believing that her brother and her lover are either dead or dying, Sonia resolves to prevent the vessel from falling into Falon’s hands and being used as a weapon of war—and she is just as ready to fight and die for a cause she believes in as any man could be. Unwisely left unrestrained by Falon (who underestimates her, as so many of us have!), Sonia determines to sabotage the vessel—and, clever girl, she knows just how to do it, too. Remember that compressed air manifold we all thought she was just pretending to take an interest in? One well-directed hand-mortar later, and the vessel is sinking inexorably to the ocean floor…

(While on the subject of Sonia, I am tempted – how unusual! – to make far too much of an essentially minor point. I watched The Relic again the other night – disliked it as much the second time around – and was just as much annoyed by everything about Dr Margot Green, including her little-black-dress-and-high-heels monster-evading ensemble. Compare her with Sonia who, recognising that she will need to be active if she’s to save herself, takes the first opportunity to rid herself of the elaborate and confining gown she was wearing when captured, and to change into some sensible clothing. Thank you, Sonia!)

Perhaps the most unexpected aspect of The Mysterious Island is how interesting it is politically. When the film opens, the mythical kingdom of Hetvia is in a state of revolt. The implication is of a peasant’s uprising, so we immediately recognise Falon as a dangerous opportunist.

Count Andre Dakkar, however, although being “one of the most powerful noblemen in the realm”, has chosen to withdraw himself from the turmoil of his homeland, and to devote himself to scientific research on his island stronghold—an enclosed community run on surprisingly egalitarian principles. Dakkar makes this known to the equally disgusted and disbelieving Falon in no uncertain terms, declaring everyone on his island to be his equal: “Here on my island, we don’t have kings or rank or power. We work with but one end: to study, to learn, to be free; to seek happiness, each in his own way…”

Fine words; and more than just words, we learn. All the same…we do rather get the impression that this tiny world of true democracy is of quite recent founding. None of Dakkar’s “equals” seems too eager to be the first to put his principles to the test. No-one, for instance, ever calls him “Andre”; he remains “Sir” and “Excellency” to the last; while even as he declares his beliefs, Dakkar himself is capable of referring to, “The workmen in my shop” and, “The peasant who tills my fields”. At the conclusion of the film, he also orders everyone out of his shipyards, “Under penalty of death”.

However, the pleasant surprise here is that Dakkar does actually practice what he preaches, even if the language in which he preaches it could do with a little revision: there is not the slightest hint, as so often is the case, that his is merely a lip service philosophy, a case of we’re-all-created-equal-but-look-at-my-sister-and-I’ll-murderise-ya. And this is all the more satisfying because the bone of contention is, literally, Dakkar’s sister. One of the nicest moments in the film is Dakkar’s ill-concealed amusement in the face of Falon’s class-conscious horror over Sonia being “insulted” by – as he puts it – a common workman! – and never mind that it was Sonia who made the first move.

Like his fellows, Nikolai has refrained entirely from presuming upon the Dakkars’ declared ideals. Although obviously as much in love with Sonia as she is with him, he has never done anything about it. This forces her to take action, in the form of some rather desperate flirting—although it is a stumble upon some convenient rubble in the workroom that finally precipitates her into Nikolai’s arms. In the aftermath of Falon’s denunciation of him, this common workman, this servant, behaves like a complete gentleman, taking all the blame of the incident to himself and steeling himself to face what he expects to be Andre’s anger and disgust. What he gets, however, is a sympathetic grin and a reassuring pat on the shoulder.

And there is another telling moment that underlines the sincerity of both Dakkars, as the diving-vessel, Nikolai in command, takes its maiden voyage. The emotional Sonia watches the launch not in company with her brother and Falon, but while standing shoulder-to-shoulder with the workmen who have toiled so hard to bring Andre Dakkar’s dream to fruition. This short scene gains real poignancy in retrospect: many of the men with whom Sonia stands so companionably will shortly give their lives for her, in an abortive attempt to rescue her from Falon.

Of course, it is noticeable that in order to create his democratic society, Andre Dakkar has had to withdraw himself altogether from the reality of life in Hetvia. Reality, however, as it has a nasty habit of doing, pursues Dakkar to his island, in the shape of Baron Falon and his revolutionary schemes. Falon tries to make an ally of Dakkar, prompting him to make history as the first of many, many, many screen scientists to utter a variation of the following impossible dream:

“I’m a scientist – who asks nothing but to be left alone!”

Whatever hope Dakkar has of being left alone evaporates in the instant that he reveals to Falon not merely the existence of his diving-vessel, but that it is armed; even Falon’s glittery-eyed declaration, “With that—we could conquer the world!”, does nothing to wake Dakkar up to what is actually going on. This is more than idealism; this is tunnel-vision: a rose-tinted vision of the world that borders on the suicidally naïve.

Well, what can I say? The plain fact is, scientists often are naïve; certainly politically naïve. The problem here is not so much Dakkar’s blithe assumption that having inadvertently created a first-class weapon of war, he will be left alone to pursue entirely peaceful purposes with it, as it is his failure to grasp the threat posed by his supposed friend, Baron Falon. As Falon, Montagu Love’s performance is so unsubtle, Falon’s villainy so broad and unconcealed – you really do expect him to start twirling his moustache at any moment – that Dakkar comes across not merely as naïve, but instead as—well, a bit thick. Consequently, when the truth finally dawns upon him, when in horror he denounces Falon for his treachery – “You!” – the audience is likely to respond not with commiseration, but with an unsympathetic, “Well, duh.”

But real calamity follows the revelation of Falon’s treachery. This betrayal, and the viciousness of Falon’s conduct, destroys forever Dakkar’s belief in the possibilities of the world, of humanity; and in consequence, the man’s real generosity and nobility are subsequently lost in his single-minded pursuit of bloody revenge.

We are so used these days to watching films in which the violent pursuit of personal vengeance is excused, if not positively celebrated, that it is somewhat of a shock when The Mysterious Island chooses to punish Andre Dakkar for turning his back on his principles and devoting himself to the destruction of his enemy—even though his doing so is entirely understandable, given Falon’s unconscionable treatment not just of Dakkar himself, but of Sonia and the workmen.

But, the film seems to argue, there is much more at stake here than one man’s sufferings, however extreme: a whole way of life is under threat.

And it is here – more or less accidentally, we feel – that The Mysterious Island finds itself back in what is recognisably the world of Jules Verne. As those well-versed in Verne-iana would know, “Dakkar” is the real name of Captain Nemo. Verne’s original vision of his anti-hero cast him as an embittered Polish nobleman, driven to madness as a result of Russian brutality. Verne’s editor, with his eye on the European market, convinced his client to remove from 20,000 Leagues Under The Sea all explicit references to Nemo’s past; and when Nemo was at length resurrected in The Mysterious Island, he had somehow become an Indian nobleman – a prince, to be exact – who had been driven to madness by British brutality!

Now, while this may in story terms have nothing to do with what happens in The Mysterious Island, the ruination of Count Dakkar’s ideals, his spiritual corruption, and his conversion from idealist to misanthrope as depicted in the film form, thematically, a perfectly valid backstory for the Captain Nemo with whom the world at large is familiar.

In fact—what Lucien Hubbard & Co. have done in The Mysterious Island, quite unwittingly, is to invent the prequel. The badly injured Count Dakkar who, having both satisfied his vengeance and killed his soul, sails away alone at the conclusion of this film – supposedly to die, but who knows? – is quite recognisable as the reluctant rescuer of castaways who would star in any of the, count ’em, six subsequent versions (so far; there are two more in development) of 20,000 Leagues Under The Sea…

It is in many ways a shame that The Mysterious Island performed so dismally at the box office, and not least so for the negative impact that this had upon the development of the science fiction film—and upon the cinematic depiction of the scientist. As a scientist, Andre Dakkar is almost a novelty: honestly devoted to his fellow man, and sincere in his beliefs; his subsequent fall from grace is depicted as a real tragedy.

But alas! – so few people saw this particular scientist in action; and of course, the next time a scientist so entirely dominated a film, he would not be embracing principles of equality and intellectual liberty, and devoting himself to the pursuit of knowledge and the betterment of mankind, but robbing graves, meddling in things best left alone, and finding out what it felt like to be God. Looking back, I can’t help but wonder how entirely different the whole evolution of the scientist in film might have been, had The Mysterious Island been a popular success, and if the initial role model for all scientists to follow had been Count Andre Dakkar—and not Henry Frankenstein…

This charming, albeit almost ridiculously premature, piece of advertising art makes it clear what we missed out on due to the shilly-shallying of all involved.

Want a second opinion of The Mysterious Island? Visit 1000 Misspent Hours – And Counting.

Speaking of costume change, the one bright shining point of a very bad movie (when those worm-things come up and attack a cruise ship, which its owner had disabled for insurance money) was when the sort-of-heroine (she start out as a thief) takes the first available opportunity to get out of her evening dress and high heels and into a pair of pants and shirt (with hidden gun).

“Scientific Consolation” – when the villain responds to hundreds of innocent victims with “Science always demands sacrifice.” I’m sure that makes them feel a lot better.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Deep Rising?

LikeLiked by 1 person

“You mean we’re in this mess because you were bad at math?”

LikeLike

Yes, that’s Deep Rising. I have it practically memorized.

Ok, let me say it one more time for the hearing impaired!

Famke Janssen (sp?) was the female lead.

LikeLiked by 1 person

“European ex-patriot” – expatriate?

LikeLike

Thank you for this. I can remember, many years ago, reading books about early science fiction film and being told that there were no prints available of “The Mysterious Island,” just stills and posters. Thank goodness for film preservation.

LikeLike

While Christensen may also have been an ex-patriot, I suspect you meant expatriate.

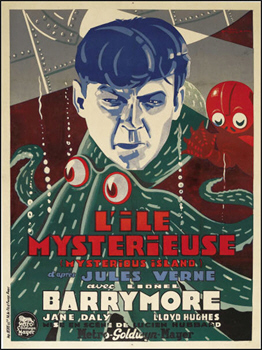

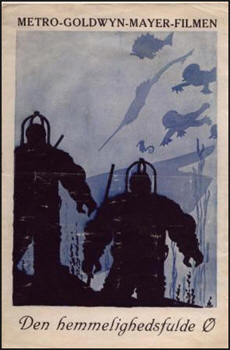

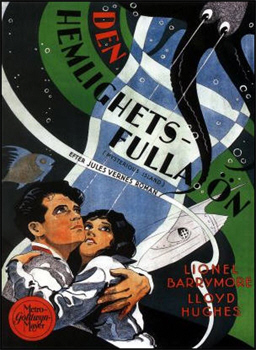

I love those drawn posters (1b, 5b, 3b, just above “It is also Hubbard”). Photographs are all very well, but paintings can be much more evocative.

Quite a few writers after Verne took the view that the submarine would be an invisible, unstoppable terror weapon. It’s interesting to see that attitude resurrected after the First World War.

LikeLike

Oh, yes, yes, yes: it’s fixed; I hope you (and Xander) are happy! 😀

I *love* that French poster!

It’s always interesting to see how thinking on a subject went so far and no further. Film-wise at least, I think the attitude to the submarine was more about the astonishing courage of the men onboard…which is how you can get a film like The Spy In Black.

LikeLike

Hey Liz,

You got a shout out from TRAILERS FROM HELL. Glenn Erikson wrote a column on “The Mysterious Island” and the possibility that the two-strip Technocolor version may soon be available. He called …AND YOU CALL YOURSELF A SCIENTIST “a worthy page” and offers a link from his column to yours.

LikeLike

Ooh, cool! Thank you for the heads-up. 🙂

LikeLike

I finally got to see this on YouTube of all places. I loved the scientific details like the need for soft and hard-sided diving suits for shallow and deep water use respectively. It showed a lot of attention to details that a lot of science fiction films would just gloss over.

The ‘warm blood in the water’ scene was so interesting. With the earlier reference to how do the sea people breathe, it implies probably quite accurately that the sea people are cold blooded. Warm-blooded metabolisms need too much oxygen to get it from gills alone. I used to love as a kid the idea in some science fiction of humans with breathing underwater, Man from Atlantis style and was dashed to find out that it just wouldn’t work.

LikeLike

Yes, there really is a lot to admire in this film. Silly 1929-ites!

You should have been there the day I realised there was a biological reason why ants couldn’t grow to be twenty-feet long and threaten the world…! 😦

LikeLike

Beautiful Technicolor print of this film is now on youtube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UaRTD6EV6lM

LikeLike