“This country’s absolutely no good anymore. So the bigwigs got together and passed this law: Battle Royale. So today’s lesson is—you kill each other off…”

[Original title: Batoru Rowaiaru]

Director: Fukasaku Kinji

Starring: Fujiwara Tatsuya, Maeda Aki, Kitano Takeshi, Yamamoto Tarō, Ando Masanobu, Yamamura Yukie (Shibasaki Ko), Kuriyama Chiaki, Tsukamoto Takashi, Takaoka Sousuke, Ishikawa Eri, Kotani Yukihiro, Ikeda Sayaka, Miyamura Yuko

Screenplay: Fukasaku Kenta, based upon the novel by Takami Kōshun

Synopsis: At the turn of the Millennium, Japanese society is crumbling. In the face of record unemployment and open revolt by the young, the government panics, passing the Millennium Educational Reform Act – or “Battle Royale” Act… The 7th grade begins badly for everyone associated with Class B. The father of Nanahara Shuya (Fujiwara Tatsuya) hangs himself on the first day of term; Nakagawa Noriko (Maeda Aki) turns up late for class, only to find that she is the only one to turn up at all; while as the class’s teacher, Kitano (Kitano Takeshi), walks away in disgust, he is accidentally stabbed in the buttock by a student, Kuninobu Yoshitoki (Kotani Yukihiro), as he flees in panic from an incident in another classroom. Two years later, the students of the 9th Grade Class B complete their compulsory education, and take their end-of-year field trip. Although he boycotted school following the stabbing incident, Kuninobu – or “Nobu” – is with his old class, having been coaxed back by Noriko. As the class’s bus travels along the highway, Nanahara notices large numbers of soldiers along the roadside. Noriko’s friend, Megumi (Ikeda Sayaka), encourages the shy girl to give the cookies she has baked to Nanahara and Nobu. Megumi takes a photograph of the other three, and Nobu complains laughingly that she has cut his head off. Later – much later – Nanahara jerks awake to find everyone else on the bus sprawled out motionless, sound asleep—or unconscious. To his bewilderment, Nanahara sees that the bus driver and a female attendant are wearing gas masks. Seeing him awake, the latter strikes him a vicious blow, knocking him out… The students regain consciousness in a darkened classroom. All of them have metal collars locked around their necks. There are also two strangers among them – “transfer students”: Kawada (Yamamoto Tarō) and Kiriyama (Ando Masanobu). A helicopter lands outside the school. From it, to the children’s dismay, emerges Kitano, who is escorted inside by some of the many soldiers that surround the building. Kitano explains that Class B has been chosen by lottery under the Battle Royale Act; and that, armed with weapons provided, the students will be forced to fight each other, kill each other, until only one of them is left alive – “the winner”. If, after three days, more than one of them is still alive, everyone dies… As the students listen in petrified disbelief, Kitano tells them that it is their own fault: that their whole generation is rotten; that they are what is wrong with Japan. He then shows them a training video intended to explain the rules of the Battle Royale—and demonstrates his exception to the whispering of one of the girls by hurling a knife into her head. After the ensuing panic is quelled, the video resumes. The students learn that they are on an island, from which everyone else has been evacuated, though the buildings and their property remain. The collars around their necks contain a tracking device. They are also explosive, and can be remotely detonated if an attempt is made to remove them, if anyone is caught in one of the island’s designated “danger zones”—or if more than one of them is still alive at the end of the game… At this, Nobu loses control and tries to attack Kitano, who takes the opportunity to illustrate just how the collars work… As Nanahara sobs over his friend’s body, Kitano orders the rest to prepare to begin the game. Called out in order of their class number, the students are each given a kit containing supplies and a weapon, and sent out into the night…

Comments: Kinji, we hardly knew ye… In what can only be considered a particularly cruel cosmic joke, when Fukasaku Kinji died in 2003 at the age of seventy-two, it was at the moment when, after a genre-spanning career of forty years and sixty-odd films, the veteran writer-director had finally achieved a deserved measure of international fame.

And the injustices of the past are only slowly being corrected, at least in this corner of the world. My choice of film to review for this Roundtable was dictated not only by choice, but by necessity: other than The Green Slime, which I had already reviewed, and the non-qualifying Tora! Tora! Tora!, Battle Royale was the only one of Fukasaku’s movies readily available in this country.

The situation is little better overseas, or at least it was until very recently. Ironically, it took the controversy surrounding the production of Battle Royale to provoke a worldwide interest in the man’s entire body of work. Prior to that, it was generally only his more conventional works – the less personal, more commercial productions – that managed to secure distribution outside of Japan. Thus, if Fukasaku Kinji’s name is associated with anything in particular in the minds of Western movie-watchers – and with the majority, it probably still isn’t – it is not with the brutal honesty of his yakuza films, or the near neo-realism of his social dramas, or even the sheer outrageousness of his occasional pop-art experiments, but most likely with…endearingly ridiculous rubber slime critters.

Still—perhaps one does get the best sense of the true breadth and depth of Fukasaku Kinji’s career by book-ending those two of his films that are best known in the West: by allowing audiences to squeal with delight at the rampaging Slime Guys, to giggle at the alpha-male antics of Robert Horton and Richard Jaeckel, and boogie on down to filmdom’s second equal first most fabulous theme song, before confronting them with Battle Royale: a film that is a steel-capped boot to the head, a knee to the groin, and a sucker punch to the solar plexus. If Kinji never received the recognition that was his due in his lifetime, at least he went out in a blaze of controversial glory—or rather, with the swing of a sickle, the flash of a switchblade, and in a near-ceaseless hail of machine-gun fire.

Much misunderstanding exists as to the alleged censorship of Battle Royale in Japan. The film was indeed held up to opprobrium in parliament, and a call was made for its banning, but in the end it was released without cuts. It was, however, and unusually, slapped with an R-15 rating, meaning that no-one under sixteen – the very people, according to Fukasaku himself, whom the film was both about and for – was permitted to see it. It nevertheless did big business; and when subsequently re-released, trimmed and with a lower rating, it did even better.

Battle Royale then did the rounds of the international festival circuit and, delighted or outraged, the word began to spread. Cut or uncut, the film finally secured cinema distribution in most major world markets. Unsurprisingly, it failed to do so in the US, although contrary to popular belief the film was never banned there. Rather, there simply wasn’t a major company game enough to touch this film, with its graphic violence and its shocking images of schoolchildren enthusiastically massacring one another, with the proverbial ten-foot pole; and for the minors, the asking price was just too high.

In adapting Takami Kōshun’s novel, Fukasaku Kinji and his son, Kenta, made the radical decision to alter the story’s background and setting. The novel is a fantasy, taking place in an alternative time-stream in which Japan was not defeated in World War II. In this context, the staging of this bloody contest can be rationalised in terms of a fascist administration finding a selection of sufficiently ruthless young people to become the next generation of leaders.

However, the Fukasakus chose to ignore this aspect of the tale, instead setting their film in their own society, but just slightly in the future—which is at once their film’s greatest strength, and its greatest weakness. It is likely that Fukasaku Kinji made this decision for the same reason that drew him to the story in the own place: his own experiences during WWII when, as a fifteen-year-old munitions worker, he and his companions came under artillery fire—and had only each other as shields. Those who survived the attack were forced to dispose of the bodies of the rest. In addition to his burden of personal guilt, Fukasaku emerged from the incident with a profound distrust of the government, having recognised how far from the truth were the regular bulletins issued about the progress of the war.

While it is understandable that, with this background, Fukasaku would wish to use the story as a criticism of the contemporary government, in a recognisable reality too much of the film’s narrative just doesn’t make sense. In particular, when the affirmed problems are a crumbling social fabric, skyrocketing unemployment, and youth in rebellion against the failures of their elders, it is hard to figure out what the slaughter is supposed to achieve. The whole thing is too elaborate to accept as merely a sadistic form of punishment or pay-back; while as a way of suppressing potential rebellion, it doesn’t remove enough potential rebels from the mix.

Moreover, since those young people who have boycotted school are declared to be the real danger to society, why pick on those students who haven’t? Other, that is, for their availability…and ease of rounding-up…

The other major flaw in Battle Royale as it stands is that no-one in Class B seems to be aware of the existence, let alone the implications, of the Millennium Education Reform Act. The film opens on a profoundly disturbing note: the media frenzy surrounding the winner of a previous year’s combat. The shot zooms in on a girl who is literally covered in blood. She does not look fifteen, or anywhere near it. She clutches a doll, emphasising her extreme youth, and as the cameras move in she smiles—showing us her braces.

As an attack on the viewer’s sensibilities, this sequence is a masterpiece; as a piece of drama, it does nothing but raise questions that the film never answers. How can the members of Class B be at the outset so blankly ignorant of what confronts them, if each year the Battle Royale is reported, dissected—perhaps even broadcast? And this raises perhaps the most unsettling question of all: just who is the audience for the Battle Royale? Were it not for that media frenzy, were the children not specifically told, “Your parents have been notified”, it would be possible to speculate that this is some kind of desperately sick underground event, a live snuff film, if you will, intended for the secret gratification of the older generation, with the eventual victims written off as just more of society’s drop-outs and criminals and runaways.

But even in that event, it seems impossible to believe that the teenagers wouldn’t know of it, particularly given the screenplay’s emphasis upon the technological savvy of several of their number. (And in any case, the orientation video alerts us to the existence of an official website!) We are therefore forced to accept that the Battle Royale is a legally sanctioned event staged for the entertainment of the public—and perhaps this does best explain why a school class is chosen as the combatants, rather than a random selection of young rebels. After all— What fun is there in watching strangers do battle, compared to that of watching close friends forced to betray one another, turn on one another, kill one another…?

But while its framework is shaky, the transference of the story from the never-was to the here-and-now is exactly what gives the film its bite. In the immediate sense, Battle Royale manages to have it both ways, playing upon contemporary Japanese society’s growing fear of a rebelling and increasingly violent youth, while simultaneously presenting its young characters as the victims of a cruel and manipulative older generation intent upon taking bloody revenge for its own failures and inadequacies.

Many of the blows of this vicious satire land squarely where they were intended to, on a culture obsessed with success at all costs, and of the system that not merely spawns but celebrates this attitude. It is no coincidence that it is a class of 9th graders that is chosen to compete in the Battle Royale. In Japan, compulsory public education ceases at the end of the 9th grade. Beyond that, the students who wish to continue are pressured into bitter competition with one another, fighting and striving for places in the best schools, the best colleges. It is a dog-eat-dog arrangement that sees the few succeed at the price of the many; one that, ironically enough, often leads to the very violence that the adults so fear; to breakdown, physical and mental, and frequently to suicide.

These outcomes are reflected very clearly in the actions of the students, once the rules of the Battle Royale are made plain to them. Some, terrifyingly, take to killing like ducks to water. Others are victims of the most helpless kind. Some play only defensively. Some refuse to play at all, killing themselves rather than killing others; while a few search frantically for a way to beat the odds, to take the battle to their tormentors, to win the game without killing.

Battle Royale is for the most past an intensely grim experience, but there is also a scattering of the blackest of humour. The film’s themes are neatly encapsulated in the experience of one of the students, a boy called Motobuchi. After the deliberate killing of one female student by Kitano, and after Nobu is the victim of his demonstration of the exploding collars, there is an understandable outbreak of hysterical panic on the part of most of the remaining students—quelled when the irritated Motobuchi yells at them to shut up, so that he can hear the rest of the orientation video: he is swift to grasp the lessons of the situation.

And later, proving that he has taken what he learned to heart, Motobuchi is seen bursting out of the cover of some bushes and blazing away with a gun—shouting as he does so at his victims, “I’m going to survive! – and get into a good school!”

Battle Royale is a film that demands repeat viewings: not only it is impossible to take in the significance of its details all at once, but this is one of those stories deepened by the viewer’s hindsight.

This is true from the film’s opening frames, which show us a class photograph of the then-7th grade Class B. The first close-up is of Kitano, but the camera then shifts to Nanahara—and it is he, one of the students, who first speaks, telling us matter-of-factly that his mother deserted himself and his father three years before, and that on his first day in the 7th grade, he came home from school to find that his father had hanged himself.

(We get another of the film’s touches of grim humour here: Mr Nanahara has left affirmations for his young son – “Go, Shuya! You can make it, Shuya!” – which are written on toilet paper.)

“I didn’t have a clue what to do,” says Nanahara bleakly, “and no-one to show me, either.” The visual juxtapositioning puts Kitano on the list of those who have failed the boy.

We later learn that Nanahara ended up in an orphanage, where his roommate was Kuninobu, who became his best friend. Nobu is another of those whom we see at the 7th grade level, fleeing in panic from some unseen incident in a classroom. There is a knife in his hand—and as he collides with Kitano in the corridor, he ends up slashing the teacher’s buttock. And while this of course lessens neither the pain nor the humiliation of Kitano, it is important that we understand that the injury was inflicted accidentally—which puts Kitano’s later actions in their proper perspective.

The other student to whom we are introduced at this point is Nakagawa Noriko: apparently so much an outsider, when the rest of her class boycotts school for the day, they don’t bother to include her. We learn later that she has been the victim of some vicious bullying by some of the other girls; nor is her popularity amongst her peers increased by the fact that the boys all like her. In fact, an awkward triangle of sorts is developing – Nobu has a crush on Noriko, who has a crush on Nanahara, who receives Nobu’s confidences without revealing himself – when circumstances make the feelings of the three young people moot.

The students wake up on the island in time to see Kitano arrive by helicopter. He is escorted into the building under an armed escort from members of the JSDF, over whom he seems to have authority. It emerges that he quit teaching after the stabbing incident—and, presumably, took a government position. For this purpose? We do not know, although we take Kitano’s later assertion that Class B was chosen at random for the Battle Royale with a healthy dose of scepticism.

After an ominous exchange with Nobu, who is told repeatedly that he is “no good”, Kitano gives a broader speech about the country’s “rotten” condition, and places all the blame for it upon the younger generation: for this reason, he adds, the Battle Royale law was passed—so that “no good” youth can kill itself off.

We are not in a position to know how Kiatno’s accusations may or may not apply in the broader sense, but his scapegoating of Class B is quietly undercut by the revelation that, whatever their issues with Kitano may have been – and vice versa – the students get on perfectly well with their current teacher, Mr Hayashida, of whom we were given a glimpse on the bus—sitting up the back and playing a game with some of the girls. So their previous behaviour, however rebellious, was evidently directed at Kitano specifically: for his inadequacies as a teacher, as a guide, even as an individual. Furthermore—Hayashida, we now learn, has died defending his students. Referring to his successor as a “no good adult”, Kitano reveals the teacher’s bloodied body…

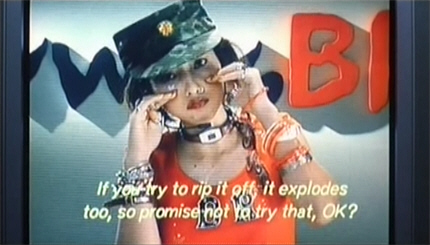

The most overt piece of humour in Battle Royale is the orientation video shown to the terrified students, which explains to them the rules of the “game”. The video features a young woman who cannot possibly be described by any word other than “perky” – although I guarantee that you’ll never see perkiness put to more utterly perverse use. With a beaming smile and a bouncy attitude, she spells out the horrors in store for the combatants: that they have three days in which to kill each other off; that every six hours, there will be a simultaneous announcement of new casualties, and of which parts of the island have been made off-limits; that the longer the game goes, the more territory on the island will become a no-go zone, being caught in which will be punished by death; that any attempt to remove the electronic collars and their built-in tracking devices will have dire consequences.

The sick comedy of this brightly encouraging spiel is underscored by its periodic interruption by shocking acts of violence. The video has barely started when Kitano hurls a knife into the head of a girl who has the temerity to ignore his interdiction against whispering. The sends the students into a panicked stampede, to which the soldiers respond with a burst of gunfire. One ricochet cuts open Noriko’s arm; she falls to the ground, crying out in shock and pain, as her frightened friends gather around her.

With Nobu, fear swiftly turns to anger: he attacks Kitano, who responds so promptly – slashing Nobu’s buttock with a knife – that we can only imagine that he intended all along to find an opportunity to do just that; had, perhaps, been fantasising about it for the past two years…

The subsequent revelation about the exploding collars sends Nobu into another frenzy, despite Nanahara’s attempt to keep him under control. It is at this point that Kitano decides that the students need a practical demonstration…

There is a pause of some seconds before the collar detonates after being triggered, and in these horrifying moments we are given a presage of what will happen once the students are sent out into battle. They are horrified and sickened for Nobu, but they are also frightened for themselves; and as he reels around in terror, begging and reaching out for help, they cower away from him—or push him away—anything to put a safe distance between him and themselves when the explosion occurs…

And all throughout, Kitano smiles delightedly…

(We note, too, that the video refers to “your teacher”, which implies that the class teacher generally fulfills the role of overseer during the Battle Royale. Though we gather that Mr Hayashida refused to participate, it is clear that Kitano always intended to take his place, one way or the other.)

The demonstrations, both theoretical and practical, being over, it is time for the game to begin. Each student is given a pack containing food and water, a map and compass, and a randomly selected weapon—which may be deadly, of only minor practical value, or totally useless, according to the luck of the draw.

This scene emphasises an important detail of the film that has already been introduced, via the premature deaths of the two students: each of the participants is referred to by their class number, which in-film allows for Kitano’s running tally of casualties—and is also a means for the viewer to get some grasp of who is who amongst the swarm of young characters, who number forty-two at the outset, including the two “transfer students”, and forty – twenty girls, twenty boys – when the game actually begins. Thus, the girl who gets the knife through her forehead is “Girls #18 Fujiyama”, while Nobu is “Boys #7”.

The students are called forward one at a time, by their assigned number. Each receives a pack, and heads out into the night.

As they go, the boys tend to make gestures of defiance; the girls, gestures of friendship. One girl, Ogawa, makes a stand immediately, refusing to take a pack with her at all. Nanahara, before he goes out, whispers to Noriko that he will wait for her. He gives her the photograph taken on the bus, which Nobu died clutching, and which is now covered with his blood…

Once outside, the students begin to respond to the situation according to their own temperaments. Some participants begin killing immediately, with deliberation or out of panic; some remove themselves from the conflict by suicide; some deaths are more or less accidental. When the first full day dawns, the initial casualty count stands at twelve. From this point the deaths taper off—much to the exasperation of Kitano, who begins increasing the number of no-go zones, in order to force the remaining combatants into each other’s proximity, and therefore into conflict.

Nevertheless, the majority of the students continue to play defensively—whether singly, in pairs, or in their usual cliques. One group of girls sets up housekeeping in a remote lighthouse, trying to ignore the situation via faux-domesticity; while some computer-savvy boys also find a retreat, where they begin to fight back against the game itself using weapons of their own: trying to hack into the authorities’ own computer-system, at first to better understand what is happening, later in an attempt – one that falls agonisingly short – to bring the whole thing crashing down…

Amongst the passive players, at least at the outset, are Nanahara and Noriko—each of whom carries their own burden of guilt. It was Noriko who persuaded Nobu to come back to school—although, as Nanahara assures her, and as indeed we heard on the bus, he was happy about it and grateful to her. Nanahara, meanwhile, was one of those who instinctively cringed away as Nobu was crying out for help in the seconds before his death—although at the last he was close enough to end up covered in his friend’s blood. Nanahara now makes two promises, in Nobu’s name: to protect Noriko, no matter what; and to find some way to take revenge for him.

But it is not always possible to avoid killing, either in self-defence or by accident, as Nanahara discovers when he and Noriko are attacked by Oki Tatsumichi—who ends their struggle with his own hatchet buried in his head. This encounter is witnessed by Sakiki Yuko, one of the girls who retreats to the lighthouse, who is not convinced that the killing is an accident, and develops a profound mistrust of Nanahara: something which will later have significant consequences.

(Absurdly, yet touchingly, Nanahara reacts to Oki’s fatal injury by gasping, “You okay?” – with an apologetic Oki assuring him, “I’m fine, I’m fine” before collapsing.)

And of course, not everyone is playing defensively. There are those who throw themselves wholeheartedly into the game—because they must, or because they want to, or in one case just for fun…

A large part of what gives Battle Royale its shock-value is that, for the most part, the film-makers eschewed the American practice of casting twenty-somethings as teenagers. Only Yamamoto Tarō, as Kawada, and Ando Masanobu, as Kiriyama, were in their twenties—which makes sense, as the “transfer students” are both meant to be a few years older. Meanwhile, the majority of the actors were in their late teens at the time of the film’s production; while Maeda Aki, Kotani Yukihiro, Mimura Takayo and Kanasawa Yukari (as Noriko, Nobu, Girls #8 Kotohiki Kayoko and Girls #6 Kitano Yukiko, respectively) were actually of middle-school age.

Consequently, when the violence erupts it is even more confronting and upsetting than it would naturally be, since those responsible for it are little more than children. There are some genuinely shocking scenes in this film—for their bloodshed; for the enthusiasm or deliberation of those committing them; and in one or two cases, for their distinct sexual overtones.

Even aside from the age of the cast-members, we are never allowed to forget that the characters in Battle Royale are teenagers—not least because, surrounded by bloody mayhem and death as they are, there always seems to be a moment to discuss who thinks who is cute, who has a crush on who – or who doesn’t – or who stole someone else’s boyfriend. And whatever angst and even violence might have stemmed from thwarted teen emotions in the setting of a school, once placed in an environment where violence is encouraged, these frustrations have their inevitable consequence, with, I hate you, I wish you were dead swiftly escalating into, I hate you, I’m going to kill you.

Moreover, the not-quite-relationships of middle-school now break out into new and, in some cases, twisted versions of themselves. We see this particularly in the interaction of Chigusa Takako and Niida Kazushi. Takako is an athlete: we see her in flashback, doing road-work; and even on the island her impulse is to don her tracksuit and work out. She is discovered by Niida; and their angry conversation reveals that Niida has been spreading ugly – and false – gossip about the two of them; also, that Niida is intent upon making it more than gossip. He starts out by telling Takako that he is in love with her, “for real”; he progresses to suggesting that she can’t want to die a virgin, right? – and then, when she scorns him, resorts to threats of rape.

But Niida has underestimated his opponent—and when he grazes her face with an accidental crossbow-bolt, Takako explodes. Her own weapon is a jack-knife and, as Niida bolts down the road, she pursues him, knocks him down, and stabs him repeatedly—concentrating her strikes upon his groin…

…only to be killed herself almost immediately, by Souma Mitsuko.

The performance of Shibasaki Ko as Mitsuko is one of Battle Royale’s most memorable – and chilling – aspects. As is implied here (and spelled out in the novel), Mitsuko is the product of a violent and sexually abusive home, and notorious at school for her promiscuity.

Mitsuko is already psychologically disturbed when she arrives on the island and, with weapons at her disposal and no restraints upon her, she cuts a swathe through her fellow-students, leaving a trail of bloody corpses in her wake. She is also responsible for possibly the film’s single most disturbing moment when, as the second day dawns, we watch her shrugging herself back into her clothing, as she strolls away from the naked, mutilated bodies of two of the boys…

Mitsuko survives to be one of the game’s last active fighters, and seems indeed a likely winner. She ultimately falls short, however—but only because she meets someone who is even more of a psychopath than she is…

One of Battle Royale’s plot-holes is the inclusion in the group of the two “transfer students”, Kawada and Kiriyama. In the novel they are properly integrated in the class before it is chosen; here, the two of them are simply there when the other students wake up on the island. It is obvious from the outset that they are “ringers”, included in the conflict for some purpose of the government’s – or Kitano’s – own. Who they are, where they came from, how they got involved goes for the most part unexplained; although Kawada later opines of Kiriyama that he is there, “Just for fun.”

We can infer Kiriyama’s overarching purpose from his actions. After all, what fun would a Battle Royale be if no-one killed anyone, if there was just a mass detonation of the collars at the end of seventy-two hours? It is, clearly, Kiriyama’s job to keep the body count ticking over, and the pressure on the remaining students—and if his job is also his hobby, so much the better.

The part played by Kawada in all this is, however, more ambiguous. Like Kiriyama, he engages in the game, killing purposefully—but not indiscriminately. He does it to defend himself, and to gain possession of more and better weapons. Thus, when he encounters the effectively unarmed Nanahara and Noriko, he only laughs and leaves them alone; later referring to them satirically as “Pot Lid” and “Binoculars”.

The three meet up again at the island’s abandoned clinic, to which Nanahara carries Noriko after she collapses with fever from her infected gun-shot wound. Nanahara hesitates before taking her inside, recognising that the building is a perfect hide; and indeed, Kawada has taken refuge there. The three of them enter into a partnership of sorts, with Nanahara and Noriko becoming more and more dependent upon Kawada’s strategy and advice: knowledge he gained, they learn to their astonishment, while becoming the winner of an earlier Battle Royale. He chose to participate again in this one, he tells them, to find the answer to a certain question…

But Kawada’s own question is only one of many. We know from the outset of the game that, in some way, the rules have been bent for him: he is called out after Ogawa, the girl who refuses a pack, and is given her rejected one as he leaves—only to appear again moments later, insisting that he has been given “the wrong one”, and to take another from the rack, without hindrance from Kitano or the soldiers. When we first see him in the field, he is wielding a high-powered rifle.

And even at his most helpful and least threatening, Kawada muddies the waters. It is he who treats Noriko at the clinic, telling Nanahara that, “My dad’s a doctor.” It is also he who prepares lunch for the three of them, responding to Noriko’s grateful praise with, “My dad’s a chef.” He appoints himself, in effect, the protector of the other two—in between repeated warnings that they can’t afford to trust anyone. And with all the contradictions associated with Kawada, it occurs to us that it might behove Nanahara and Noriko to take that last piece of advice at face value…

Like Kawada, Kitano is a riddle only slowly solved—and never entirely so, although we can draw our own inferences. What he is without any question is the face of the older generation: that generation which has failed, and now takes out its frustrations and inadequacies upon the youth of the country; something we see, as it were, in microcosm, as Kitano interacts with his former students.

For all that he tries to shift the blame for his own failures onto the incident with Nobu, it is evident that Kitano and the students despised each other well before that. No doubt the kids made his life miserable; but no doubt either that he was a lousy teacher. As far as that goes—the early scenes on the island play out like every teacher’s deepest, darkest, wish-fulfillment fantasy, as Kitano’s scapegoating of his former students escalates first into verbal abuse, then into physical—and then into fatal violence. Meanwhile, we learn that his personal life, too, is a mess: his marriage is falling apart, and his young daughter hates him.

A brief conversation between Kitano and Kawada towards the end of the film tells us more about both of them than either has revealed to that point. For one thing, they know each other—at least from the time of the Battle Royale in which Kawada was the winner, since Kitano is aware of the personal issue that brought him back. This in turn implies that Kitano has been involved in the Battle Royale since he gave up teaching—and it is impossible to escape the conclusion that in doing so, he was simply biding his time: waiting for Class B, his Class B, to reach the right age…

Over the course of the Battle Royale, it slowly becomes apparent that the conflict is in some measure being “fixed” to favour the survival of one particular individual; in fact, there is a subtle visual hint as to this outcome very early in the film. Gradually, too, we grasp that this is Kitano’s doing—and that Kawada’s inclusion may have been intended to help bring it about.

But just because Kawada has been playing Kitano’s game for him, this does not preclude the possibility that he has simultaneously been playing a game of his own…

In some respects, Battle Royale is a contradiction in terms: a film of frequent, confronting violence; a brutal, sometimes blackly humorous satire; and yet functioning primarily on the level of character.

Certainly it is to the film’s cast that much of its effectiveness is owing, each member of which brought both energy and conviction to their character—and not least, Kitano “Beat” Takeshi in the film’s only significant adult role. It is he who really sells the improbable concept of the Battle Royale, even as he builds a character who is, by turns, terrifying, appalling, and blackly funny; who by the end we might find—well, a little sad; even a little pathetic.

But it is upon the shoulders of its younger actors that the success of Battle Royale finally rests. All of them are solid, including leads Fujiwara Tatsuya, Maeda Aki and Yamamoto Tarō; but the stand-outs are Masanobu Ando as the psychotic Kiriyama, Kuriyama Chiaki as Takako and Shibasaki Ko as Mitsuki. The latter, in particular, is nothing short of terrifying.

(It is interesting to reflect that for both young actresses, their violent characters proved to be break-out roles: Quentin Tarantino cast Kuriyama Chiaki in Kill Bill Vol. 1 on the strength of her work here, while Shibasaki Ko went on to a successful career as an actress, model and singer.)

It is one of the real strengths of Battle Royale that its characters never behave like anything other than the teenagers they are—whether swearing eternal friendship, or taking out a long-held grudge. Perhaps the most worrying thing about this film is that there is nothing here that isn’t psychologically convincing—nor, for that matter, that most teenagers don’t know already: that you can’t trust anybody, least of all adults; that to be vulnerable is to invite destruction; that being cool is worth dying for…

The film grants a number of the characters, as they die, a kind of epitaph: their lives summed up in a few words. Here, even Mitsuko achieves a measure of pathos, as she speaks not only for herself, but for all of life’s runners-up: “I just didn’t want to be a loser any more…”

Meanwhile, for the viewer Battle Royale can function as an interesting kind of personality test, particularly in terms of the choosing of an identification figure. The audience is certainly encouraged to identify with various of the characters—but given that the film adheres with absolute ruthlessness to the principle of anyone can die at any time, doing so can be an unsettling experience.

For myself, in philosophical terms I was most in sympathy with Utsumi Yukie, who is one of those cut down by the hail of bullets unleashed by a mass-panic at the lighthouse, and who dies wailing, “We were so stupid! Stupid!”; in practical terms, with another of the girls, Mayumi Tendo, who is the game’s first true victim—getting an arrow through her throat before she even properly understands what is happening…

Though now nearly twenty years old, Battle Royale remains a jolting experience. Among the more controversial films of the modern era, it is one of the few that drew critical fire for its violence alone: a point which is worth pondering. That this is a very violent film goes without saying; but it is not the violence per se that is the issue, but rather who is committing it—and that the film plays it so straight. There is a measure of black humour here, certainly, but a few absurdist moments aside, it is never at the expense of the victims.

On the contrary, the deaths of these frightened, bewildered young people are, as they should be, painful and upsetting. The countdown of casualties serves its purpose within the film, but it also serves a greater one of identifying each victim by name. These are not the one-dimensional constructs of too many slasher films, who exist only to be butchered: each character, no matter how brief their appearance, is real to us. The violence committed by them, and against them, is never casual, never faceless, never painless, never fun.

In short, Battle Royale is a serious film, with a serious point to make; and only those who haven’t bothered to look past its admittedly gore-drenched surface could dismiss it as mere exploitation. It may not be a great film – there are a few too many holes in its fabric for that – but it is an unforgettable one: a film that gets deep inside your head and does some serious mischief to your psyche. It is outrageous, confronting, and thoughtful all at once; and as such, a fitting coda to the equally outrageous, confronting and thoughtful career of Fukasaku Kinji.

♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦

This review is part of the B-Masters’ tribute to director, Fukasaku Kinji.

This is a little morbid, but when I first watched this, I wanted to cheer when the teacher threw the knife at the whispering student. I occasionally work as a substitute teacher.

LikeLike

😀

I once had a student (not substitute) teacher who liked to throw chalk—which is what Kitano starts out doing. But she doesn’t take the hint…

LikeLike

Thanks for not mentioning the H movie like so many people feel the need to do. This film is much better.

LikeLike

Well, (i) I haven’t seen it, and (ii) this came first, so there’s no reason to. If I ever get around to the H movie, I suppose I might feel the need…

LikeLike

The books are better than the movies (big surprise). To me, the most interesting part of the H universe was how society was set up. The people in the capital had no concept of the idea of hunger, and were completely oblivious of how the other 90% actually lived.

Nothing like today, of course.

I can’t help thinking how well something like this would work today. I bet it would get great ratings. If you could take out the ending of “Certain death for all but one” somehow, I could see it being a contender in the fall season.

LikeLike

That scene showing how the explosive collar works seems to me to call back to Wedlock (1991 Rutger Hauer vehicle, I rather like it though I’d readily admit it’s not good) – in particular the way everyone tries to get away from Mr Beepy Neck.

LikeLike

My copy of Wedlock is under the much cooler original title of Deadlock. I rather like it; what’s not to like? Rutger Hauer, Dexter’s dad James Remar, Danny Trejo, Stephen Tobolosky as the smarmy warden. Well, ok, it does have Mimi Rogers from the era where she converted Tom to Scientology and so we can all hold that against her and this film. (Or enjoy it if you like see Tom crashing and burning).

Of course, I’m a bad example for taste in movies. I just rewatched Slave Girls from Beyond Infinity about a week before the Most Dangerous Game review appeared here.

LikeLike

The exploding collar is a marvellous device for this sort of film, providing a reasonable and ongoing explanation for the eternal question of, “Why are they doing these things?”

Of course Wedlock / Deadlock isn’t in the same ball-park as Battle Royale, but it’s sufficiently fun in its own right.

LikeLike

It’s been awhile since I’ve seen this, but the whole reveal at the end really had me scratching my head (no spoilers for those who haven’t seen it but it involves the painting seen in one of the screen shots). What was that all about? That and the plot holes you mention at the beginning really bugged me. Not enough that I couldn’t appreciate it, but it was distracting. I’ll mention the H movie! In it’s defense Hunger Games the novel (which I assume got a lot of inspiration from this) does a much better job of coming up a plausible explanation for having teens battle to the death than Battle Royale. While the basic premise is unavoidably similar it goes in a different direction. Politically, the book is much more about class struggle than generational struggle. The film version unfortunately softens the violence which has the effect of making it MORE exploitive, in other words it loses the impact and becomes more of a mediocre action film. I saw it and the first sequel but honestly I remember little about them, but I don’t think I’ll ever forget Battle Royale, despite its flaws!

LikeLike

Well, there were numerous hints leading to that conclusion; although in practice you’d think it would be impossible to ensure one particular outcome.

But yeah, the re-setting of the film creates a raft of problems that are never solved.

And you’re right: they never seem to realise how toning down violence, or not showing it, actually makes things worse not better.

LikeLike

The H makes it clear that this stuff is being broadcast, which seems to me like a perfect way to annoy people into mass insurrection, as indeed happens. Obviously it’s necessary for the plot, but it’s a stupid way of reinforcing the idea that you’re in charge.

(Obvious political comment is obvious so I won’t make it.)

LikeLike

Just released on Looper YouTube channel minutes ago. Movies with plots stolen from other movies including The H Movie theft of Battle Royale.

LikeLike

More correctly, it is (or may be) a book with a plot taken from another book…or a book with a plot taken from a movie. You can’t actually blame a movie for being like the book it’s based on. 🙂

LikeLike

Wild and crazy thought that is probably just me. I don’t remember if it was the first or second Battle Royale, but I remember the Radetzky March being used. At an island with people trapped on it. And I immediately thought of The Prisoner that used the same music. Maybe the Free for All episode.

LikeLike

No, that might well be a deliberate allusion. Well spotted!

LikeLike