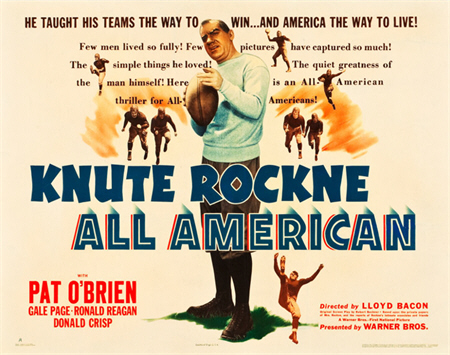

Director: Lloyd Bacon and William K. Howard (uncredited)

Starring: Pat O’Brien, Gale Page, Donald Crisp, Ronald Reagan, Albert Bassermann, Owen Davis Jr, John Qualen, John Sheffield

Screenplay: Robert Buckner

While we’re accustomed to Warner Bros. films that are cynical in outlook and disrespectful in tone, and which evince a healthy suspicion of authority, occasionally there was an exception that proved the rule. And when the producers did decide to be patriotic and/or sentimental—my goodness, they could lay it on with a shovel…

Such is the case with Knute Rockne All American, a fulsome yet superficial biopic of the great Notre Dame football coach. We have a pretty good idea of what we’re in for from the opening credits which, in addition to their slavish thanking of Notre Dame itself for its cooperation, assert that Robert Buckner’s screenplay is “based upon the private papers of Mrs Rockne, and the reports of Rockne’s intimate associates and friends”. We are not, therefore, expecting anything critical of Rockne or even just balanced—and we certainly don’t get it.

(Notre Dame’s grip on this production was absolute: the institution vetoed the casting of James Cagney as Rockne because he was on record as supporting the anti-Nationalists in the Spanish Civil War.)

From its opening scenes, Knute Rockne All American displays a great determination to leave no cliché undeployed. We follow the Rockne family from Norway to Chicago, where – as the right sort of immigrant, you understand – father Lars Rockne (John Qualen) secures a high-level, well-paying job with almost embarrassing ease, and young Knute (John Sheffield) discovers, in the streets of his new home-town, “The most wonderful game in the world!”

A swiftly passing montage has John Sheffield turning into Pat O’Brien, and shows him slaving away to earn enough money to put himself through college. He subsequently enrols at Notre Dame as a rather mature freshman…

…much more mature than was even the case. I gather that Pat O’Brien is both made up to look rather like Rockne, and does a good job of reproducing his staccato speech-pattern. However—he was forty-one when he was cast (two years younger than the real Rockne was at the time of his premature death), and the film makes no effort to disguise the fact, making the early scenes involving this “star college athlete” more than a little absurd. It doesn’t help that the film-makers lightened O’Brien’s hair to reflect Rockne’s Scandinavian background: it just looks like he’s going prematurely grey.

Anyway… There’s a reason – a distressingly brief reason – while this film qualifies for Science In The Reel World, and we might as well get it out of the way as quickly as the film does. Lost in the sands of history is the fact that when Knute Rockne enrolled at university, it was to undertake training in chemistry.

Even while building his football career, Rockne emerges as the star student of Father Julius Nieuwland (Albert Bassermann), Notre Dame’s professor of chemistry and botany. Father Nieuwland has high hopes of his protégé, and offers him a summer job as his own assistant in his efforts to develop a form of synthetic rubber. He suffers the first of many setbacks when Rockne apologetically declines, explaining that he has already committed to a summer job as a life-guard in company with his friend and roommate (and teammate), Charlie “Gus” Dorais (Owen Davis Jr): a job that allows Rockne and Dorais plenty of time to work on their football tactics…

Father Nieuwland does not give up, however, and when Rockne graduates – magna cum laude – he is again offered a job, this time as a teacher: a position he accepts on condition that he is allowed simultaneously to accept a post as assistant football coach; excusing himself via his need to earn enough to get married on. He starts out promising that he will only coach for a year, just long enough to get on his feet financially: “You don’t think I’m crazy enough to take up coaching as a life-work, do you?”

Knute Rockne All American does offer a few scenes of Rockne and Father Nieuwland at work in their chemistry laboratory, but we all know how the story ends; at least, we all know how Rockne’s story ends. Probably less well-known, though it shouldn’t be, is that Father Nieuwland’s research into acetylene eventually contributed to its use as the basis of a type of synthetic rubber, and paved the way for the development of neoprene by DuPont.

Not that anyone associated with this film was at all interested in that.

Having held his two jobs for three years, Rockne knows he must make a choice; and he turns for advice, or rather for absolution, to Father John Callahan, the President of Notre Dame (played by Donald Crisp at his most unctuous: Callahan is the film’s one overtly fictional character; I’m not sure of the significance of that). Callahan urges Rockne to take up whichever work is “closest to your heart”—and that’s the last we hear of science.

Sigh.

The rest of Knute Rockne All American is devoted to a dash through Rockne’s coaching career and his influence upon the game of football. The film follows him through his years of staggering success as Notre Dame’s head-coach and his introduction to the game of such innovations as the forward-pass-based offence and the backfield shift. It also shows him as a role-model not just for the young men he coached, but for young men all across America: propagating a personal code of honesty, clean-living and hard work.

And of course there are a few difficult times—most significantly, the game against Army in 1928, when – with the breaks beating the boys – Notre Dame was in danger of significant defeat. But not to worry: Rockne has just the dressing-room speech for the occasion…

Find a copy of Knute Rockne All American today and you’ll probably find Ronald Reagan’s image on the cover rather than Pat O’Brien’s—a tendency that gives no hint of the brevity of Reagan’s presence in the film. True enough it is, and sad enough, that George Gipp died at the age of only twenty-five, of a Streptococcal throat infection that led to pneumonia, just as he became Notre Dame’s first elected All-American. Whether he actually made his dying speech, in which he supposedly urged Knute Rockne to have his boys “win one for the Gipper”, or whether the story is apocryphal, is by this time beside the point. We would, however, hope that matters did not unfold as they are shown here, with Gipp’s family led away so that he can address his last words to his football coach.

By 1931, the rocky times have passed: so much so, that Knute is finally able to make good on a seventeen-year-old promise, and take his wife and children away to Florida for the winter. Even here, however, his commitments pursue him. Apologetically, he tells Bonnie (Gale Page) that he must break up his vacation and travel to California; though to make his absence as brief as possible, he proposes to travel by plane. He laughingly waves away Bonnie’s instinctive protest against air-travel…

Knute Rockne died on the 31st of March, 1931, when one of the wings of the Transcontinental and Western Air Fokker F-10 on which he was travelling broke up in flight; the plane dropped from the air and crashed near Bazaar, Kansas, killing all eight people on board. The scenes with which Knute Rockne All American concludes, in which it depicts the national outpouring of grief that followed Rockne’s death, are perhaps the most accurate aspect of the film.

Knute Rockne All American is generally regarded as one of the great films about sport, and in that respect it is indeed successful, capturing the early days of college football and the development of the game under Rockne’s revolutionary approach. The film uses newsreel footage of real games throughout, and while this is not exactly seamlessly blended with the studio-created football scenes (jersey numbers come and go, grounds change, and so on), in itself this footage is a fascinating time-capsule for those interested in the history of the game.

At the same time, as a biopic this is a profoundly unsatisfactory film, chiefly because it won’t admit to anything that might reflect poorly on Rockne or, by extension, Notre Dame. It won’t even admit that Rockne ever did anything, good or bad, not directly associated with Notre Dame itself—ignoring his years as a professional football player, for instance. The film is also so determined to put Rockne on a pedestal, it can hardly concede he ever made a mistake: the rocky patch preceding the famous Army game is there chiefly to set up the “Gipper” scene, after which Rockne is elevated to that pedestal once again. The result of all this is that the film’s version of Knute Rockne is two-dimensional platitude-spouter, rather than someone capable, through his shrewd thinking and forceful personality, of shaping both a sport and the men he coached.

There is no hint here of Rockne’s determination, while building a winning culture, equally to make Notre Dame football a financial success; or of his skilful manipulation of the sports media of the day, to the benefit of his team and himself; or of his own lucrative side-career as an advertising spokesman. Least of all is there any reference to the fact that the proud educational institution of Notre Dame paid its football coach $75,000 a year: at the time, an unprecedented sum.

Though it ends, as noted, with Rockne’s death, Knute Rockne All American precedes its concluding tragedy with a scene in which Rockne is called to testify before a committee investigating the shocking allegations that college athletes are being given financial incentives—and even worse, a soft ride through their academic requirements. Rockne not merely rebuts these allegations, at least as far as his athletes are concerned, but gives a stirring speech about football’s many benefits to America: its building of character and teamwork, how it prevents “softness” in young men, how it provides a safe outlet for “combativeness”. Rockne expands upon this last point—informing the Committee that America doesn’t have wars or revolutions because, unlike in Europe, its young men play football.

(There’s not just only one kind of football in this film, there’s practically only one kind of sport.)

Now—while much of this is self-evidently ludicrous, something very interesting – and very sneaky – is going on here. In the years leading up to the bombing of Pearl Harbor, Warners fought a constant battle against America’s isolationist position, with greater and lesser degrees of success: sometimes bringing the wrath of Washington down upon itself, sometimes successfully reaching the public with its message.

And in this climactic scene, it slowly becomes evident that Knute Rockne All American is – or is being used as – another of Warners’ “preparedness” films. It is not by accident that the studio chose to make this film during 1940; and this scene, which overtly offers football as an alternative to war, is actually selling football as a preparation for war: a way of ensuring that America’s young men are fit, well-drilled, able to work in teams and used to following orders—so that they’re ready when the call inevitably comes…

But while it is not without these flashes of interest, I have to say that, overall, I find Knute Rockne All American a bit tiresome—and very artificial. That’s just me, though: I know many others find it inspiring. And in fairness to this film, I need to point out that something else is operating here: the fact that, not so long ago, I became aware of College Coach, which – although it came first – could fairly be considered this film’s evil twin: another Warners production that also deals with college football, and also casts Pat O’Brien as an influential football coach—but which is in all other respects as distant from Knute Rockne All American as it is possible for any film to be.

Knute Rockne All American now feels like—not merely a rejection of, but an apology for, College Coach: going as far in the opposite direction as is possible, and replacing the earlier film’s sneering, cynical attitude towards college sport with a blinkered sanctimony that is, quite frankly, just as hard to swallow—if not harder. I ended my review of College Coach by admitting that it made me feel a little sick; so too does Knute Rockne All American—just in a very different way…

Footnote: Pat O’Brien completed the triumvirate by starring in 1943’s The Iron Major, a low-budget biopic depicting the life and career of football coach Frank Cavanagh. It is a film very much on the Knute Rockne side of the scale…

Like I said: with a shovel…

For a while now I’ve been avoiding biopics of recently-dead people, because they’re always utterly laudatory – because the people who own the material needed to make the thing at all won’t stand for anything else. I’m glad, I suppose, to see that this isn’t a new problem.

As someone who has a vague recognition of the name “Knute Rockne” but couldn’t tell you which state Notre Dame is in, I think you’ve told me all I need to know about this one. 🙂

LikeLike

This is one of the reasons College Coach is so fascinating: it was made only two years after Rockne’s death and pretty much pisses on everything he stood for (or was believed to stand for). Maybe someone got sick of the hype?

Indiana. Though the film assumes you know that (I don’t think it ever says).

At this distance it’s hard to say but I believe I would have seen this film on TV when I was quite young; it wouldn’t have been anything other than “just a film” at the time. Later, of course, it took on quite a significance: I’m now incapable of thinking of ol’ Ron except as George Zipp, or of not adding the line, “…and I won’t smell too good, that’s for sure” to the Gipper speech. 😀

LikeLike

He graduated Magna Cum Laude, and never used his degree? (except for that 3 years of teaching) What GPA is that?

And yet another movie to teach America’s young boys and men that they don’t need no stinking larnin, they just need to be good at sports.

LikeLike

Oh, well. At least science was second in his heart…even if a very distant second.

Sigh.

To be fair Rockne is shown as insisting his players work at their studies and keep their grades up (and without outside assistance). But this is one of those annoying “sport as a metaphor for life” films, so it isn’t really about coaching football, it’s about molding young men.

LikeLike

Cagney was vetoed for “anti-nationalist” sympathies? Lordy.

I had to look up which side of the Spanish civil war that term applied to. And wikipedia directed me to an article about anti-Catalanism, which was interesting though not relevant.

LikeLike