“At moonrise the rocketship will ascend into space. And, God willing, we will land – thirty-six hours later – on the far side of the moon…”

[Original title: Frau im Mond]

[aka By Rocket To The Moon, Girl In The Moon]

Director: Fritz Lang

Starring: Willie Fritsch, Gerda Maurus, Gustav von Wangenheim, Fritz Rasp, Klaus Pohl, Gustl Stark-Gstettenbaur, Karl Platen

Screenplay: Thea von Harbou, based upon her novel and a book by Hermann Oberth

Synopsis: Aeronautics magnate Wolf Helius (Willie Fritsch) calls upon his friend, Professor Manfeldt (Klaus Pohl), to find him almost throwing a visitor to his rooms down the stairs. Manfeldt was once a respected scientist, but was rejected by his peers over his radical theories concerning space travel and the presence of gold on the moon. Though proudly refusing financial assistance from Helius, the Professor is persuaded to share a simple meal with him. Afterwards, Helius announces abruptly that he has decided to go to the moon. The Professor is almost hysterical with joy, insisting wildly that he must go too, before collapsing in tears. Helius comforts him, assuring him that he may, and adding that now, his theories will be proven correct. However, when the Professor assumes that Hans Windegger (Gustav von Wangenheim), Helius’ chief engineer, collaborator and friend, will also form part of the crew, Helius withdraws from him, saying quietly that he will not. By way of explanation, Helius hands to the Professor the invitation he has received to the engagement party of Windegger and Friede Velten (Gerda Maurus), Helius’ brilliant student—and the woman he also loves. When Helius tells the Professor that, as yet, no-one but himself knows about his decision to launch the rocket being built at his facilities, he is warned that others do know: that the man thrown out of the Professor’s apartment was trying to buy the manuscript of his space-travel theories and that, several nights before, there was an attempted break-in, apparently also with the aim of securing the document. The Professor presses his manuscript upon Helius, begging him to lock it in his safe. However, a coordinated attack upon Helius’ apartment and Helius himself robs him of all documents pertaining to his rocket and the planned launch, including the manuscript. Though his own phone has been put out of order, Helius uses a neighbour’s to call Windegger, insisting that he come at once in spite of the engagement party. Windegger is reluctant but, overhearing, Friede intervenes and tells Helius that both of them will come as soon as they can. Returning to his apartment, Helius finds a visitor waiting for him, whom he recognises as “Mr Walt Turner of Chicago” (Fritz Rasp), the man thrown out of the Professor’s rooms. Turner identifies himself as the representative of the heads of the world’s most powerful gold syndicate, who have heard of his plans and the Professor’s theories, and have no intention of allowing new supplies of gold to flood the market—or to be in the control of anyone but themselves. Turner tells Helius that his proposed trip to the moon can only happen in collaboration with the syndicate, or he will not be going at all… Hearing of the thefts, Windegger goes to check his own documents, leaving Friede and Helius alone together. Seeing that he is keeping the full truth from her, Friede presses Helius until he admits that he is intending to undertake his trip to the moon, but did not wants his plans to separate her from Windegger. Friede responds coolly that he certainly will not go without Windegger—nor without her… Meanwhile, the threats of the syndicate must be dealt with: when Helius hesitates to give in, there is an explosion at his hangars. No great harm is done – this time – but the implications are clear; and Turner is accepted as part of the crew. Work on the rocket is completed and soon, as the world looks on in awe, mankind’s first journey to the moon gets underway…

Comments: “Science fiction” is such an all-embracing term that it is often found necessary to break it up into subcategories—the most telling of which may be “hard” and “soft”. While the latter can encompass almost anything, much greater demands are placed upon the former: in essence, that a film simultaneously adhere to accepted scientific principles while telling a story that, at a minimum, relies upon a reasonable extrapolation of current knowledge. And while this framework can be applied to any branch of scientific advancement, traditionally it has most often been applied to that which to many people represents the most extreme form of human endeavour: space travel.

It is not perhaps surprising, given these criteria, that genuinely hard science-fiction films are few and far between; yet throughout the history of film – indeed, from film’s earliest days – there have been ventures in this area that have proven, with the benefit of hindsight, almost eerily prescient.

Probably the most famous among this subset of films is 1950’s Destination Moon, but it was not the first. That came as early as 1929, in Fritz Lang’s Frau Im Mond – Woman In The Moon – which like its American descendant painstakingly incorporates contemporary understanding of astrophysics and engineering into its depiction of the first manned flight to the moon.

Other than that, however—the two have almost nothing in common.

Destination Moon is a rare work even in this relatively limited branch of film-making in being basically nothing but hard science: there is almost nothing in its plot that does not pertain to the immediate problems of building a rocketship that will travel to the moon, and how to get home afterwards. Its characters barely have personalities, and rarely express an emotion—or talk about anything but their immediate situation.

Woman In The Moon, meanwhile, is for most of its running-time a distinctly unrealistic adventure full of melodrama and emotional angst, which plays fast and loose with science except for its famous central set-piece of a rocketship blasting off and travelling to the moon.

Nevertheless—what Woman In The Moon gets right, it gets completely right; in some respects, to an even greater degree than its more focused descendant.

That mention of the running-time of Woman In The Moon raises the first of a number of side-issues which must be addressed in dealing with this film. Like all of Fritz Lang’s silent works, this is, or was, a very long film; but also like all of Lang’s silent films, it has been roughly handled over the years, and exists in a variety of forms. This treatment is, perhaps, more understandable, if no more forgiveable, with respect to Woman In The Moon than Lang’s other efforts: what we will unavoidably think of as “the good bit” occupies almost the very centre of this film, with a full hour and a quarter of machinations and hand-wringing preceding the first appearance of Helius’ rocket.

It was when the film was released in America that this situation was dealt with most ruthlessly: its distributors simply lopped off this entire opening section, offering a 95-minute version that wasted no time getting to its launch sequence…even if it did leave its viewers confused over who exactly the characters were, what the relationships were between them, and what some of them were doing there in the first place.

To be fair to the Americans—in the early seventies, there was a West German release that ran only 91 minutes; but most countries, though they cut less savagely, nevertheless did cut; so that the original 200-minute version barely saw the light of day after its initial release, until a full restoration was undertaken in 2000.

Unfortunately the full print remains anything but readily available; and consequently, this review is based upon the Kino DVD release of 2004, which runs 169 minutes.

Though its American manifestations are no doubt better known, in the 1920s Germany was equally gripped by what was referred to, with distinctly disapproving overtones, as “rocket fever”. Even while real-life pioneers in the area of rocket design faced scoffing and resistance to their ideas, the reading public was devouring anything to do with rockets, from the wildly speculative to the purely scientific.

The era’s critical publication was, intriguingly, one of the latter: in 1923, one of those discouraged pioneers, refusing to take ‘no’ for an answer after having his doctoral dissertation rejected by his assessors, turned it into a pamphlet and published it.

The pamphlet, as the thesis had done, made four startling assertions: that it was possible to build a vessel that could (i) rise above the atmosphere; (ii) achieve escape velocity and leave the Earth’s gravitational field; (iii) carry a human crew; and (iv) travel between planetary bodies (something which the author envisioned becoming, in due course, a profitable business venture). It also described how the construction of such vessels might be undertaken, including the necessary properties of their propellants.

Hermann Oberth’s Die Rakete zu den Planetenräumen (“By Rocket into Planetary Space”) turned out to be a landmark work in the history of rocket design and space travel, inspiring a rising generation of scientists and mathematicians—and a rising generation of science-fiction writers. An explosion of “space-flight novels” followed the publication of Oberth’s pamphlet, most of them offering a similar plot: a visionary hero overcomes social and scientific obstacles while constructing a rocket; he and his crew travel to a planetary body (usually, though not always, the moon), facing dangers and technical difficulties both in space and on the surface; and eventually he returns to Earth, to be greeted as a hero by the public and the now-shamefaced nay-sayers.

One of those who ventured into this field of writing was Thea von Harbou, who was an established novelist before she turned her talents to screenwriting. In 1928, she published Frau im Mond (“Woman in the Moon”), which followed the template almost exactly, except for including among the rocket’s crew the eponymous woman. The novel was a success in Germany, and translated into English in 1930 – and, sadly, infantilised – as “The Girl In The Moon”. (In its most recent English-language release, the title was changed to “The Rocket To The Moon”.)

In her afterword to Frau im Mond, von Harbou acknowledged three non-fiction works as instrumental in inspiring her novel: Otto Willi Gail’s Mit Raketenkraft ins Weltenall (“By Rocket into Space”) and Willy Ley’s Die Moglichkeit der Weltraumfahrt (“The Possibility of Space Travel”), both published in 1928—and, inevitably, Hermann Oberth’s seminal Die Rakete zu den Planetenräumen.

In 1929, Fritz Lang decided to transfer his wife’s space-flight novel to the screen, arguing that the central vision of space travel was both “realistic” and “romantic”. Lang himself had no interest in the technological revolution that had gripped much of Germany, and knew that in spite of von Harbou’s own reading, his film, if it was to achieve his own vision of scientific accuracy, would need a qualified advisor—and despite the recent rapid growth of this area of research, only one person seemed to fit the bill.

During the five years after the rejection of his thesis, Hermann Oberth had only become more certain of the practicality of his theories, and was busy turning his pamphlet into a book (which when finished would run over 400 pages). He had also become something of a cult figure, as well known to the public as to the scientific community. The proposal made to him by Fritz Lang appealed to him as a way of taking his ideas to an even broader audience, hopefully with the consequence of increasing funding for his work and that of others: the German government having proven obstinately resistant in this area, all research was being privately funded.

Lang, in turn, was fully alive to the possibilities for publicity inherent in attaching Oberth to his film. In fact, in the first burst of their mutual enthusiasm, the two men seem to have gotten a little carried away: early in the process, they agreed that as a way of promoting the film, Oberth would actually build and launch a test rocket.

Though in retrospect this seems like an absurd publicity stunt, it was undertaken in all seriousness, even to contracts naming Fritz Lang and the film’s production company, Ufa, as financial beneficiaries of any future projects eventuating from a successful test. Hermann Oberth certainly took it seriously—but at that point he was a theorist rather than a practical scientist, and in trying to turn his theories into realities within an impractically short timeframe he made a series of mistakes and bad decisions that saw the project stumble through failure after failure, and suffer postponement after postponement – to a time far beyond the release date of the film the rocket was supposed to promote – until, drowning in debt and stress, he abandoned his efforts altogether and fled back to his home in Transylvania.

Oberth’s frantically conducted practical research was not entirely without results, however…but that is something we shall return to a little later.

Woman In The Moon premiered in Berlin on the 15th October 1929. Audience reaction to the film’s central space-flight sequence was everything that could have been desired, being greeted with gasps and applause; while its impact upon sceptical scientific observers was still more striking, prompting a widespread reassessment of many of the associated theories.

As for the reaction to the rest of the film, it was similar to what it tends to be today: we-ee-ee-llll…

Woman In The Moon opens with a closeup of a small placard spelling out the qualifications of a Georg Manfeldt, who holds a PhD and a professorship in astronomy…but whose other professional affiliations have all been struck out. There is immediately a burst of action, as a small, rather scruffy man thrusts another, much larger individual out of his rooms and almost pushes him down the stairs. The man is saved from a rough landing by another visitor, provoking the ire of Professor Manfeldt, who insists furiously that the newcomer should have let “that skunk” break his neck.

Questioned by his visitor, whom he addresses as “Helius”, the Professor explains angrily that his unwanted caller had tried to buy from him a certain manuscript, merely as a curiosity.

Helius tries, unsuccessfully, to calm the Professor down, leading him back into his rooms. These are almost bare of furniture, although in the corner by the one tiny window sits a telescope; while over the Professor’s poor bed, a thin mattress on the floor, hangs a globe: not the usual model of the Earth, but one of the moon.

As he enters, Helius finds a visiting-card which states simply that the caller was one “Walt Turner of Chicago”, a mere glimpse of which is enough to send the Professor into another rage.

Helius unpacks a parcel on the Professor’s small table, while the Professor himself carries his single comfortable chair – a chair that, at least, would be comfortable, if it had more than three legs – from its place before the telescope into the middle of the room, propping it up again with a pile of books. (He keeps a designated pile of just the right height.)

We see that Helius has brought with him meat, butter and wine; tactfully, he asks the Professor if he can spare a little bread, so that the two of them might share a meal? This prompts another outbreak from the Professor, who draws from his pocket a banknote which, he says angrily, he found in his pocket after Helius’ last visit. Spurning what he calls Helius’ charity, he adds sardonically that if he wants bread, he can buy it with that.

Helius must then work to overcome the Professor’s wounded pride, before he can persuade him to share what he has brought. When he finally does, the Professor wolfs down the meat and wine supplied by his friend in a manner that shows only too clearly how infrequently he has anything to eat but bread.

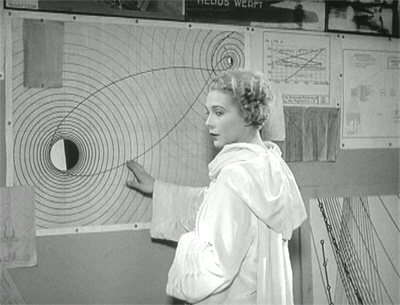

During the meal – in the course of which Helius as the guest occupies the rickety chair, while the Professor sits on a wooden crate – Helius gazes around at the walls of the small room, which are covered with hand-drawn renderings of the Professor’s astronomical observations and a whole series of charts, diagrams—and newspaper clippings. The camera closes in on one of these, which includes a caricature of a much-younger Manfeldt; the headline is translated for us into English:

FOOL OR SWINDLER?

We are also shown that the article is dated 1896: as the Professor remarked earlier, bitterly, he has been “suffering for his ideas” for some thirty years.

A flashback follows—and for the very first time in the history of the science-fiction film, we watch as, first with mockery and then with anger, a scientist is driven out of the scientific community for the radical nature of his ideas.

This scene stems from Thea von Harbou’s novel, and if it didn’t capture the practical reality of such moments – which, as Hermann Oberth must have known, tended to be rather more clinical: the rejection of a thesis, a refusal to publish – it may have been viewed as capturing the emotional reality.

There are many historical landmarks along the way in Woman In The Moon, and this is surely one of the most important: nothing less than the creation of one of the genre’s ur-figures, the outcast scientist, bitter and brooding, living only to prove himself right and “the fools” wrong.

Only two years after Woman In The Moon we would have another such seminal moment in James Whale’s Frankenstein: Henry Frankenstein making an impassioned plea for the wonders of intellectual curiosity before observing bitterly that, “If you talk like that, people call you crazy.” Five years more, and Boris Karloff’s Dr Laurience would be experiencing exactly what Professor Manfeldt does here, being driven out with laughter and scorn in The Man Who Changed His Mind.

Indeed, so rapidly did the makers of science-fiction films seize upon this situation – usually linking it with some idea so bat-shit insane that you can hardly blame the scientific community! – that it was soon deemed unnecessary to spell out the details. One glimpse of a scientist alone in some isolated country house or, in some cases, a castle – or if not alone, in company with some poor, put-upon assistant; hunchback optional – and the viewer would know exactly what they were in for. The radical theories and the consequent expulsion could be taken for granted.

But all this had its origins here, as we watch a much-younger Professor Manfeldt expound upon his twin-obsessions: first, that travelling to the moon in a rocketship is entirely feasible; and second, that the moon is rich with deposits of gold.

This in itself neatly sums up the weird, split-personality nature of Woman In The Moon: its mixing of hard science and silly pulp-fiction, which makes it so often a rather disconcerting experience.

As it happens, the congress to which Professor Manfeldt is presenting his theories is equally unopen to both suggestions: its members – not one of whom appears to be a day under seventy, and most of whom are rocking some serious whiskers – respond with incredulous, mocking laughter. Stung to the core of his being, Manfeldt explodes into anger, insulting his colleagues as “idiots” and “ignoramuses” and provoking an angry uproar…

…as we fade back to the present, and watch Manfeldt picking every last scrap of meat from the bones of the cooked chicken which Helius brought with him. Helius, meanwhile, is gazing long and thoughtfully at the Professor’s lunar-globe. Abruptly, he announces: “I have made up my mind to go.”

The Professor’s reaction is one of hysterical joy. “But not without me, Helius!” he cries, “Not without me!”

Reassured on this point, Manfeldt collapses in tears.

Helius’ casual announcement that he has “made up his mind” to go to the moon tends to provoke laughter, but we soon learn that not only does he mean just what he says, he has almost completed the means of doing it.

In addition to noting the many “firsts” along the way in Woman In The Moon, it is impossible not to make point-by-point comparisons with its American descendant, Destination Moon. This is one the most intriguing: like the later film’s Jim Barnes, Helius is an aeronautical magnate, the head of a company large enough, and successful enough, to undertake something as outrageous as the construction of a vessel capable of travelling to, and landing on, the moon. (Helius seems to be even better off than Barnes, who must seek supplementary funding and other resources from his fellow-magnates.)

It is interesting to ponder whether Robert Heinlein, on whose story Destination Moon was based and who worked on the screenplay, lifted the idea from Woman In The Moon, or whether it represents a kind of parallel evolution—since the power of private industry, as opposed to mere government, is one of the later film’s main themes. It may well have been the latter; and in any event, Destination Moon handles this subplot more seriously and sensibly than does Woman In The Moon.

For one thing, we get the impression here that Helius’ construction of his rocket was undertaken mostly as a theoretical exercise, just to see if it could be done: the vessel is now nearly finished, without any formal plans in place to, uh, take it for a test-drive; and it is something distinctly earthbound that finally prompts Helius to start thinking of a moon-shot in concrete terms.

The wildly joyful Manfeldt begins planning Helius’ proceedings for him, but gets no further than an assumption that Hans Windegger, his friend and chief engineer, will also form part of the crew. Brusquely, Helius rejects this suggestion—and by way of explanation, shows the Professor his invitation to a party, where the engagement between Windegger and Friede Velten is to be announced.

Yup: sorry, folks; it is indeed a love-triangle, and a particularly exasperating one.

Helius’ rejection of Windegger as a crewmember is not out of jealousy, but a rather annoying (and self-congratulatory) nobility: it is so that he and Friede will not be separated, nor Windegger placed in danger. To this end, he, Helius, has not told anyone about his plan to go to the moon, except for Manfeldt. But even as he explains this, the Professor has a moment of alarming insight, insisting that others do know: he tells Helius about an attempted break-in, which seemed aimed at securing his manuscript of astrophysical theories, which preceded the attempt of “Walt Turner” to obtain the document by purchase.

The Professor also concludes – correctly, as it turns out – that the real point of interest here is not space travel or rocketry, but his theories about gold on the moon. He presses his precious manuscript upon Helius, begging him to keep it safe. This proves a tactical error: on his way home, Helius is waylaid, drugged, and robbed of the document. Simultaneously, via an elaborate deception, Helius’ apartment is infiltrated and all his documentation relating to the planned launch stolen, as well as a scale model of his rocket; while it will later transpire that Windegger, too, has been robbed of all of his papers.

This section of Woman In The Moon is unnecessarily protracted, and blends some awkward (and rather misplaced) humour into the thriller-plot—including with respect to the introduction of the Professor’s only other friend, a mouse (called “Josephine”) who lives in the walls of his apartment. It also serves to introduce what at first seems to challenge the love-triangle as the most unwelcome aspect of the film (although it turns out not to be): the Cute Kid, a young boy called Gustav who lives near Helius, and who is obsessed with “space” and “space travel”. Gustav’s passionate consumption of American dime-fiction dealing with these subjects is one of the film’s more successful touches of comedy.

(As the last few paragraphs make quite clear, in writing her space-flight novel, Thea von Harbou left no cliché undeployed.)

The infiltration of Helius’ apartment is accomplished via a meek individual bearing a letter of recommendation from Hans Windegger. When Helius’ apologetic housekeeper explains this, he telephones Windegger to get at the truth of the matter—catching him in the middle of his engagement party. Helius then insists that, party or no, Windegger must join him immediately, so that they can discuss the developing crisis. Windegger, however, hesitates—and it is Friede who assures Helius that both of them will come at once.

As an ambivalent Helius ponders an encounter with Friede, who he has been avoiding, he is suddenly confronted by the man he saw being thrown out of the Professor’s rooms…

This formal introduction of “Mr Walt Turner of Chicago” is one of the film’s more unnerving moments. In the first place, contemporary German audiences would have recognised him instantly as the film’s villain, because Turner is played by Fritz Rasp, who rarely played anything else. Next, the camera pans down to rest upon his spats—which would have told viewers that, whether or not his name really was Walt Turner, he was American (and possibly from Chicago).

But neither of these details is what will rivet the attention of modern viewers, but rather the character’s unmistakably Hitler-ian hairstyle.

Of course, we say that now; the intriguing question is whether people would have said so then…and if so, what Thea von Harbou thought about it.

Though they had at the time of this film’s production been married for a decade, the personal relationship between Fritz Lang and Thea von Harbou had essentially gone bung after only about a year, even as their professional collaboration went from strength to strength: foundering equally on his serial infidelities and her increasingly ring-wing politics.

It suited them both to stick it out, however—at least until the Nazis’ rise to power, at which point Fritz Lang responded to an offer from Joseph Goebbels to head up the new, Nazi-fied national film industry by fleeing both his country and his wife. He never looked back, and he and von Harbou never met again.

(Some reassessment of von Harbou has suggested that for her, it was less about politics and more about a fixation with charismatic leaders able to sway multitudes: she was as devoted to Gandhi as to Hitler.)

Turner’s first move, after introducing himself, is to take out a key and let Helius into his own apartment. Perhaps the film’s most genuinely startling moment follows, as Turner confirms that he was the meek-looking individual with the fake letter of introduction: he illustrates his words with one of the production’s few special effects unconnected with the space-flight, apparently rearranging his own face and then putting it back again.

“Now I understand how you have evaded prison so long, Mr Turner,” observes Helius, to which Turner responds, equally wryly, “You flatter me!”

This overly-extended fencing finally – thankfully – settles down into a revelation of what, exactly, Turner and the people he represents are after…which is, naturally, those mountains of gold that, some thirty years before, Professor Manfeldt assured a mocking world were to be found on the moon.

Three years before Woman In The Moon, Fritz Lang was savagely berated by the critics for the “political naivety” of Metropolis. Apparently he took it to heart, because in this, his next science-fiction venture, he offers instead a deeply cynical scenario of worldwide, endemic corruption—and of the helplessness of the idealist in the grip of capitalist self-interest.

In short, the people behind Turner are an international syndicate – its members billed in the credits as “the brains and chequebooks” – who between them control the world’s gold, and who have no intention of allowing this new source of the metal to flood their market.

While this subplot is not without its amusing side, Woman In The Moon devotes way too much time to it without ever working out the details. We’re left to infer (from Turner being forced on Helius as another crewmember) that the syndicate wants possession of the gold—and not just to prevent others possessing it, although that’s actually what they say. But how exactly do they plan to go about getting it? The film never really tries to answer this question. The conspirators could certainly stop Helius from getting to the moon at all, as they make ominously clear to him, but the idea of them forcing him to pack-mule mountains of gold from the moon to Earth for them is just ridiculous.

(No more ridiculous than there being mountains of gold in the first place, granted…)

Be that as it may— This is the first point in the film where its science really makes itself felt, as we cut away to the members of the gold syndicate – one of whom is Japanese, another a cigar-chomping woman – as they examine the stolen documents and the model rocket. One of the five holds up a photograph of the lunar surface, exclaiming excitedly about its contents: its shows a bright magnesium flash, proof that Helius’ unmanned trial rocket reached the lunar surface and exploded upon impact. (A note reveals that the flash was observed and photographed at the Mt Wilson Observatory.) Furthermore, stolen film contains details of the design and launch of the trial rocket, and images of the surface transmitted during its orbit, including from the never-before-seen dark side.

There is a thrill associated with this part of the film infinitely more profound than any provoked by its actual thriller-plot; while the sudden switch from the pulpy machinations of the film’s bad guys to absolutely straight science is quite jolting.

At the same time, in pursuing the cutting-edge of contemporary knowledge, Woman In The Moon illustrates just how far off the mark were some of the prevailing theories—and if we recognise that these were real theories, it makes the gold-plot a little less silly. As the camera pans past the lunar surface, intertitles quote real-life scientists including the Danish-born German astronomer, Peter Andreas Hansen, of the Gotha Observatory in Germany, who believed that there was “atmosphere and therefore life” on the dark side of the moon, and the American William Henry Pickering, of the Mandeville Observatory in Jamaica, who interpreted the haze observed within some of the moon’s craters as swarms of insects.

As the film concludes, the wheelchair-bound member of the syndicate makes clear their position:

“The moon’s riches of gold, should they exist, ought to be placed in the hands of businessmen and not into those of visionaries and idealists!”

…or to put it another way, scientists.

We then cut back to Turner delivering the syndicate’s ultimatum to Helius: that the journey to the moon will be made under their command, or it won’t be made at all. Then, from insisting that Helius give in at once, under threat of his hangar and the rocket within being destroyed, Turner concedes him twenty-four hours to make up his mind.

Intriguingly, in his first passionate rejection of Turner’s threat, Helius speaks of colonising the moon, a point never raised again.

Windegger and Friede turn up hard on the heels of Turner’s departure, and Helius tells them about the thefts; that and no more. Impetuously, Windegger runs off to see whether Friede’s guess is correct, and he too has been cleaned out—leaving Helius alone with Friede for the first time since the announcement of her engagement.

Ultimately, the character of Friede and the way that Gerda Maurus is used in Woman In the Moon may be the film’s biggest letdown. The most immediate aspect of this is also the most obvious: though Friede is presented as a “brilliant student”, and though she has presumably been involved both in the designing of the rocket and the planning for its (theoretical) journey, in-film we never see her doing any science.

This is not, however, an example of a familiar science-fiction film shortcoming, but a deliberate choice on the part of Thea von Harbou. Friede is not here to be a scientist, but a symbol: an inspiration to the men in an immediate sense, and more broadly the embodiment of the spirit of human enterprise, always striving, always yearning… There’s no subtlety at all in this aspect of the film, which finds Friede spending most of her time clasping her hands on her breast, or putting them together prayer-fashion, and gazing heavenward, like some sort of astronomical Joan of Arc.

This is tiresome enough in itself, but there is a creepy aspect to it too, at least with hindsight; Friede in her entirety looks unnervingly like one of the heroines of the so-called “mountain films” so popular in Germany in the 20s and 30s, a number of them made by and starring Leni Riefenstahl. This peculiarly German artform – regarded by some as the German equivalent of the American western – is often interpreted allegorically, as an expression of the spirit and of the supremacy of the human will…even its (ahem) triumph…

As with Friede’s posturing, this was clearly a conscious choice by von Harbou—for whom, perhaps, merely climbing mountains without any safety gear wasn’t a strong enough expression of character: her model Germans would climb to the moon.

And there is a third, far more prosaic level, upon which Friede ultimately disappoints. Woman In The Moon reunited Gerda Maurus and Willy Fritsch after their co-casting the previous year in Lang’s espionage romp, Spione (Spies). In that film, their relationship is unconventional and a great deal of fun, and Maurus is allowed to be a proper action-girl; here, Maurus and Fritsch are simply two points of an all-too-conventional – and irritatingly mopey – triangle.

It is clear from the outset that Friede was initially drawn to Helius, but then drifted towards Windegger when he didn’t notice; while he, in turn, probably being too caught up in his work, didn’t realise his own feelings until the announcement of the engagement. Friede will spend the rest of the film zig-zagging between the two men, according to whichever of them seems to need her more at that time—and just to add the final dollop of icky to the situation, her attitude towards both comes with overtones that are unmistakably maternal in nature. Though Windegger does get in a couple of early kisses (speaking of icky), more commonly we find Friede cradling one man or the other in her arms and holding his head or stroking his hair to comfort him in a moment of crisis.

After they have been alone together for few tense minutes, Friede asks Helius abruptly why he didn’t reveal to her and Windegger his intention of going to the moon? After some evasions, Helius admits that he wanted to avoid forcing Windegger to choose between love and duty. To this, Friede responds simply that he will certainly not be going to the moon without Windegger…nor, for that matter, without her.

Tempora mutantur. This is the one interesting touch in the tiresome triangle-plot. Helius almost explodes at the suggestion that Friede might form part of the crew, insisting categorically that she cannot be permitted to take such risks and put herself in such danger (we learn at this point of several brave pioneers who have already lost their lives in failed ventures into space), that he could not stand it; whereas Windegger – although he puts in terms of her wanting to go with him, rather than her going in her own right – is, after the first moment of shock, delighted. We are clearly supposed to deduce from this that Helius loves her more…but what the modern viewer sees here is Windegger treating Friede as an equal and allowing her to make her own decisions. In fact, Windegger is never more likeable than at this moment, nor is the engagement ever more explicable.

Helius finally explains to the others about his position with the syndicate…but nevertheless lets the twenty-four hour deadline drift by without responding to the ultimatum. Word then reaches him of an explosion and fire in one of his hangars: there is only property damage, and no loss of life…this time, says Turner. And Helius capitulates…

And it is at this point, 76 minutes into Woman In The Moon (and 6000 words into this review, eep!), that the film’s celebrated set-piece unfolds: the completed rocketship – which, by the way, is called the Friede, translated for us as “peace” – emerges from its hangar and is prepared for its journey to the moon as an astonished world looks on.

This really is a marvellous sequence, generally succeeding in evoking the intended sense of awe in spite of some fairly obvious model-work. However, as always, the black-and-white photography helps here, and any flaws are more than offset by the evident excitement and belief of the people behind the scenes in its creation.

We are in a position today to recognise what viewers in 1929 could not, the prescient accuracy of the majority of this material. First and foremost – getting correct what is the most significant error in Destination Moon – Helius’ rocket is multi-stage: the jettisoning of the first stage and the firing of the second are made an important aspect of the extended launch / escape sequence. The rocket has been constructed within an enormous hangar; it is moved out to its launch-pad via a massive platform on sliding railings, and eventually positioned within a buffering water-pool; it operates on a specially-designed liquid fuel. Inside, there are both dangling hand-straps and loops inserted in the floors, into which the toes may be slipped. During take-off, the crewmembers battle the G-forces while lying horizontally in bunks.

Furthermore—the last moments before launch are accompanied by a countdown. It is generally conceded that this procedure, which we now take for granted, was invented by the makers of Woman In The Moon.

But even while they go toe-to-toe in their efforts for scientific accuracy, what is really striking here is how completely different are the tones and approaches of Woman In The Moon and Destination Moon, in handling essentially the same material.

The first really significant difference here is that never at any point in the presentation of its scientific content does Woman In The Moon talk down to its audience. There’s no Woody Woodpecker here, and – more importantly – no Joe Sweeney. For the most part, Woman In The Moon simply presents its concepts in a straightforward manner, and clearly expects that the average viewer will grasp them, if not entirely, then sufficiently to follow what’s going on. This may reflect the extent to which Germany really was gripped by “rocket fever”. To be fair to Destination Moon, though, it does explain its science in more detail.

Moreover, in stark contrast to the rather paranoid political atmosphere and air of secrecy that pervades the later film, reflective of Cold War America, here we have optimism and openness. Everyone is thrilled and excited about the prospective launch, with no hint of disapproval or interference from either government or enemies, foreign or domestic. Huge crowds gather to witness the launch (some enterprising soul seems to have sold tickets!), cheering wildly as the hangar-doors open and the rocketship begins its stately journey to the launch-area. Those in attendance even attempt to storm the barriers, and have to be held back by police, with some women becoming hysterical. Photographers and newsreel cameramen swarm all over the site, capturing every detail for posterity. A radio broadcaster describes vividly every moment to a listening world. We learn from him that at the moment of lift-off, “Bells will be rung, sirens of all factories, trains and ships all over the world will sound in honour of the pioneers of space navigation!”

Mind you…on the rocketship, things aren’t quite so chipper.

The final crew consists only of those whom we have learned to expect, with one addition: Helius, Windegger, Friede, Turner, and Professor Manfeldt…who has brought along his mouse. (There is lots of lecturing here about the anticipated pressure on the human body, but that is NOT what I was concerned about!)

As they make their final preparations, Helius again stresses the dangers for the benefit of Turner and Manfeldt. As a sign of professional respect, he refrains from offering the same warnings to Windegger and Friede…or at least, he tries to: he can’t stop himself from begging Friede one last time not to do this, to leave before it is too late, and is only halted by her asking if he really intends to shame her like that?

In fact—Friede is full of beans. She spends her final moments on terra firma shaking hands with the project’s many workmen (I was reminded here of the Countess Sonia’s comradely relationship with her brother’s workers in The Mysterious Island, also 1929), then climbs briskly up the rope-ladder to the boarding-platform; pausing in the doorway to pose for one last photograph and one final wave goodbye. Once inside, she shows no sign of apprehension until the very moment of lift-off.

The same cannot be said, however, for Windegger.

This is something which rapidly became a cliché of the space-flight film, but it too had its origins here: you could always tell how an individual character was going to fare during any given film by how they conducted themselves during lift-off; and heaven help anyone whose lip quivered while waiting for that decisive moment, or who lost their subsequent battle with the G-forces too quickly.

This is the point in Woman In The Moon at which the love-triangle readjusts itself. Helius, all angst and outbursts in the early stages, becomes Mr Cool once actually in command of his rocketship; while Windegger, wildly enthusiastic about the journey in theory, is reduced to a sweaty mess once its dangers become real to him.

The film’s one egregious error occurs during the take-off sequence, during which the rocketship both lifts off and then accelerates with absurd rapidity. This is accompanied by its silliest artistic choice: the rocket’s controls are on a panel in the middle of the floor, between the bunks occupied by Helius and Windegger—rather than, say, over their individual bunks. The two men are therefore required to lean awkwardly across, fighting the G-forces all the way, in order to eject the first stage, ignite and then eject the second, and eventually bring the ship out of acceleration.

It is perhaps needless to say that Windegger fails dismally at his assigned tasks, passing out first of all the crew with the G-forces (they all go eventually) and leaving Helius to carry out both his own tasks and his engineer’s…which he completes just in the nick of time, not much to our astonishment.

Now—when I called the over-acceleration Woman In The Moon’s one egregious error, I meant its one unintentional error. From this point the film junks its scientific accuracy and reverts back into a pulpy adventure-story, full of things that everyone knew even at the time just weren’t true, like an enveloping breathable atmosphere on the moon, no real difference in gravity (everyone wears weights on their shoes, but are not otherwise affected), an ordinary night-day cycle rather than a fortnightly one, plenty of water (which must be found, if you please, with a divining-rod)—and, yes, there are huge deposits of gold. The bad-guy machinations that dominated the opening section of the film also re-emerge and take over the plot.

Ah, well. It was fun while it lasted.

All the crewmembers eventually come round (yes, including the mouse!), and there is a celebration that demonstrates the superiority of German space-films to American ones, in that they reach not for sandwiches and a harmonica, but brandy. Friede goes to pour out—and in doing so helps to demonstrate Thea von Harbou’s completist tendencies: yet another cliché-box is ticked with the revelation of a stowaway (few German space-stories were without one). It’s Gustav, the space-obsessed kid from Helius’ neighbourhood.

(Hereafter, he, Helius and Friede are repeatedly framed together, like a surrogate family.)

The rest of the journey also hits the familiar marks, with the crew gazing in awe first at the receding Earth, and then at the approaching moon; having fun with weightlessness; and struggling with a landing that goes wrong, and which is further complicated by both Windegger’s growing funk – he does nothing from this point on but throw petulant tantrums – and the Professor’s growing hysteria.

Disturbingly, there is a suggestion here that the Professor wants the ship to crash, as a sort of all-embracing consummation of his life’s work. While, in films using this subplot, the outcast scientist usually does come to grief while pursuing his vindication / revenge, having a few screws work loose in the process, few of them have ever handled the mental-health consequences of exile and ridicule as straightforwardly as this one. Already in a parlous condition when the adventurers set out, the fulfillment of the Professor’s dreams brings him to state of combined exaltation and selfish ruthlessness in which he is quite prepared to risk his companions’ lives. While Windegger spends the journey clinging desperately to thoughts of Earth, the Professor’s gestures indicate an angry rejection of that scornful globe, and a dangerous desire to embrace the moon on a permanent basis.

As the rocketship approaches its destination, Helius and Windegger cannot pull it out of its rapid descent: it over-speeds down as it over-sped up, finally plunging deep into the powdery lunar surface – which saves the life of everyone on board – and sustaining damage requiring repairs if they are to have any hope of taking off again. (Although this latter point is treated as only a temporary inconvenience.)

Windegger’s only thought, once arrived, is to get the hell out of there: he is morbidly thrilled to discover that one of the water tanks is damaged, arguing that this means they cannot stay. The Professor, meanwhile, terrified that Windegger might convince Helius that they need to leave at once, or (as he threatens) try to leave by force, ignores all orders and protocol by rushing into a spacesuit and exiting the ship—and so achieving his life’s dream of walking upon the moon.

He also solves the question of a breathable atmosphere, by striking a series of matches and then discarding his helmet.

From the main cabin, Helius watches in dismay through his binoculars as the Professor recedes into the distance, apparently being dragged up and over the dusty hills of the moon by the divining-rod.

An argument then breaks out amongst the others about the best order in which to undertake their various tasks, which Turner unexpectedly solves by offering to go and search for the Professor—and hopefully finding some water, too. He sets out, following the trail of footprints.

Meanwhile, Gustav is helping Helius to write up the log (the latter injured his hand during the landing); a sulky Windegger works at removing the piles of moon-dust from the lower levels of the rocket; and Friede sets up a camera and begins filming the lunar environment.

This is the only moment in the film in which Friede does something sciencey, so, enjoy!

There is a fraught moment when Friede subsequently discovers and treats Helius’ injury: a tear falling upon his hand alerts him to the altered state of her feelings, but after an involuntary, betraying response the latter tears himself away from her and announces that he, too, is going to go looking for the Professor, who has now been missing some hours.

As it happens, the Professor is at just that moment fulfilling the second great wish of his life. The divining-rod leads him into a cave full of bubbling springs (although not hot-springs, by the way everyone wades through them), and then through it into a chamber which is indeed full of the deposits of gold which he predicted. After shrieking aloud in triumph, the Professor clasps in his arms an almost man-sized stalagmite of gold, kissing and caressing it as if it were indeed a person. (It actually looks a little…reptilian; even dinosaury. Hmm…)

Now— Turner is not of course remotely interested in either water or the Professor per se, and unfortunately he arrives on the scene just in time to hear the magic word “GOLD” echoing through the cavern. Observing him, the Professor screams in fury, wrenching his metallic love-object away from its surrounding rocks and fleeing with it into an adjoining chamber. (This may be another nod at low gravity, or just sloppiness.) Turner pursues him and, as he backs away, the Professor does not notice the crevice behind him. He plunges to his death, broken by the jagged rocks below and crushed by his pillar of gold…

Only momentarily disconcerted, Turner collects a few samples of the abundant gold and heads out. Catching sight of the searching Helius and Gustav, he dodges behind some rocks to avoid them, and leaves them to make the grim discovery for themselves.

The silliest part of the film then unfolds, or maybe just the least explicated—with Turner apparently trying to steal the rocket. We can only assume that he thinks he has gleaned sufficient knowledge from the stolen material to get back to Earth on his own. Otherwise, his various attempts to abandon and/or murder the crew seem just a tad counterintuitive…

Nevertheless—this section of the film does offer the moment that, science and space-flight notwithstanding, I always remembered most vividly from my first viewing of the cut-down American version, lo, these many years ago. (It’s the only moment in Woman In The Moon where I could recognise the Gerda Maurus I knew from Spies.)

While Turner is overpowering and trussing up Windegger, Friede is developing her films in a makeshift darkroom. When Windegger does not respond to her calls, she goes out looking for him, with Turner holding his captive silent in the hope that Friede will wander far enough away from the ship for him to commandeer it and lock the others out.

However, when Turner releases Windegger to make a dash for it, the other shrieks a warning, initiating a race to occupy the ship. Friede gets there first, but then faces a desperate struggle to hold Turner out of the cabin—one which she ultimately “wins” by using her own arm as a locking bar, despite the agony inflicted by Turner’s wrenching efforts to get the door open.

Helius’ arrival puts an end to her torment. A furious hand-to-hand fight begins between the two men. At the same time, Gustav manages to untie Windegger’s arms. Thrown free from Helius, Turner draws a gun—only for Windegger to produce one as well. There is an exchange of shots, one wild, one on the mark—

—and it’s Turner who bites the dust, literally. Weirdly, he gets a drawn-out, ain’t-it-sad death-scene (which is certainly more than the Professor got!); but our surrogate family’s solemn overseeing of his last moments is rudely interrupted by an hysterical Windegger, who has discovered that Turner’s wild shot has damaged the rocket’s oxygen tanks—meaning that, even though the crew now only numbers four – or even three-and-a-half – if the others are to make it back to Earth, someone will have to stay behind…

Bet you didn’t see THAT coming.

With Friede and Gustave ruled out of the running, it boils down to a two-out-of-three short-stick draw between Helius and Windegger—and the latter gets the worst of it.

A base-camp is constructed on the surface some distance away, with a tent erected and anything that could remotely be of use offloaded from the ship. Fortunately, it seems like they initially planned to stay for some time. (When they say the rocket has a cargo hold, they ain’t kidding!) Meanwhile, Windegger is not taking his situation well, to put it mildly. Finally, Friede offers to stay with him—but he is so wrapped up in his misery, he doesn’t even hear her.

Helius does, however. He is pouring three drinks, with which they can share a last toast—and into two of them he slips a sedative. Windegger chugs his, but after one taste of hers Friede glances suspiciously at Helius. Nevertheless, she is soon retiring to her sleeping-quarters complaining of headache, even as Windegger collapses where he is.

Left alone with Gustav, Helius must put the weight of the situation on him. He explains to the boy the initial take-off procedures, making him run through the routine until he is perfect, and promises him that Windegger will wake up in plenty of time to take command for the rest of the journey.

Helius leaves a note for Windegger, in which he expresses his confidence that he will come back for him as soon as he can. He wants desperately to take one last look at Friede, but resists temptation and turns away from her door. The parting with the tearful Gustav is difficult, but the boy promises valiantly that he will carry out his duties. (This is one of several moments in Woman In The Moon where they assume the science to be understood: there’s no explanation of why Gustav will have no pressure-troubles lifting off from the moon.)

Helius then exits the ship, leaving Gustav to seal up the vessel. He retreats to a safe distance, counting down on his watch—and lifting his head to watch his rocketship blast away from the surface of the moon.

Alone – as alone as any man has ever been – Helius turns towards his base-camp…

…where he has a surprise waiting for him.

I’m not sure how we’re supposed to take the ending of Woman In The Moon. It’s certainly startling, whatever we conclude: so few films have the nerve to leave their protagonists’ fate unresolved.

Of course, technically Destination Moon also leaves its characters’ fate undecided, in that it closes with them still in space. However, that film’s can-do attitude leaves no room for doubt that the men will make it safely back to Earth. Here, not so much.

It is interesting to note the range of interpretations provoked by this ambiguous close over the years, from the optimistic to the uncertain to the doom-ridden to the political.

In this context it is worth remembering that Woman In The Moon has had half-a-dozen different scores imposed upon it since its first release, and the accompanying music certainly influences how we view its final scenes. The Kino version comes with a new score composed by the remarkable Jon Mirsalis, which gives the ending a distinctly elegiac feel…but who knows? – perhaps the original score suggested a hopeful and even triumphant moment.

But—I don’t really think so; not if the fate of Helius and Friede rests upon the efforts of Hans Windegger.

The note that Helius leaves contains a frank demand for quid pro quo, but let’s be realistic: not only does Windegger evince a state of terror throughout the entire space journey and his time on the moon, thinking of nothing but getting back to Earth again, but his interactions with Helius and Friede are punctuated (not unjustifiably) with outbursts of jealous rage. And given that he is yet to wake to the realisation that Friede preferred to stay behind with Helius rather than travel home with him—well, I’m not seeing much that promises an altruistic response from him.

What’s more, I don’t believe Windegger ever learns that the Professor was correct about the gold on the moon, so we can’t even find hope in his self-interest.

Actually, now that I come to think about it—I don’t think I’d care to be in Gustav’s shoes, once Windegger does wake up…

Woman In The Moon went on to become the highest-grossing film of the 1929 / 1930 German production season: an enthusiastic public response that we must set beside the critical response, which was universally negative. There were various reasons for the latter, including the frankly political. By this time Ufa was owned by Alfred Hugenberg, a far right-wing media mogul who at this time was openly supporting the rising National Socialist party, and was perceived (and to a large extent, correctly) as using his film company as a propaganda machine.

More leftist reviewers of Woman In The Moon were not slow to read within it an alarming allegory (Aryans conquering new worlds, rather than dying on dead ones; what was the original intent of the ending!?); von Harbou was pilloried for her politics, and Lang for doing deals with the devil in order to get his films funded (the distinction was almost invariably made).

In fact, it can hard to appreciate in hindsight just how widely unpopular the Lang / von Harbou partnership was at the time: they were seen as the public face of reactionary forces, having their strings pulled from behind a curtain.

But while we must of course consider the political climate of the time, it is perhaps a more relevant fact that Lang and von Harbou were also unpopular simply as film-makers. Here too von Harbou took the brunt of it: even aside from her politics, she was perceived as simplistic and derivative in her writing; many critics derided her as a drag upon Lang, from which he would not or could not free himself, preventing him from achieving true artistry.

Yet some critics of the time were just as dismissive of Lang himself, condemning him as old-fashioned and out of step with international developments in film-making. (One wonders how they would have reacted to the knowledge that Lang would go on to a twenty-year-long secondary career in Hollywood.) And of course, given that this was 1929, in one important sense Lang certainly was “old-fashioned”: sound was on its way, and at a rate of knots; and Woman In The Moon would be the director’s last silent film.

Another common criticism of Lang is that his films were just “sound and fury”, and in the case of Woman In The Moon it is hard to argue. The film’s many flaws are almost thrust into our faces: it is over-long, with many of its scenes unnecessarily drawn out; much of its plot is frankly silly; and in order to go along with what Lang, or von Harbou, or both, seem to have considered its BIG themes, Lang ordered BIG acting: silent-movie gesticulation of the broadest and most tiresome kind, which persists throughout.

(The only subtle moment in the entire film is when Friede suspects her drink has been drugged: Lang foregrounds Windegger’s exaggerated agonies, so that it is possible to miss altogether her quick look at Helius.)

Even the central set-piece didn’t please everyone. While some critics embraced it as film-making, as a realisation of the technological cutting-edge and as an expression of human possibilities, others sniffily dismissed it as “juvenile fantasy”, or complained about the model-work. Amusingly, some of the latter also complained about the film’s “boring” moonscapes, demanding something out of Verne or Wells instead. This is actually another of the film’s points of accuracy, although with a certain measure of artistic license for plot-purposes.

But if in public people were in two minds about Woman In The Moon, behind the scenes it was a very different matter.

The film, as I remarked earlier, sparked a serious reconsideration of the theories of rocketry which it champions. It also provoked a new burst of activity on the part of the Verein für Raumschiffahrt (“Society for Space Travel”), an amateur organisation that spent every cent it could raise on experimental rockets, and which by 1930 had achieved the first successful test-firing with liquid fuel. Among its members at this time were Willy Ley, who had also consulted on Woman In The Moon, Wernher von Braun—and Hermann Oberth, who was president of the organisation.

Oberth emerged from his self-imposed seclusion in 1930, in order to take up again the practical side of his work, which the time-pressures associated with the “publicity stunt” had driven to embarrassing though ultimately very informative failure. So enthusiastic did these amateurs become about their rapid progress at this time that they began petitioning the government for money. Such funding was permissible, since when the otherwise punitive Treaty of Versailles was laying out its restrictions upon military development in Germany, the possibility of rockets was overlooked…

There is surely no better measure of the accuracy of the science in Woman In The Moon than the fact that when, in 1933, the Nazis embarked upon the research program that would ultimately produce the V-2 long-range guided ballistic missile, their first step was to ban the film from any further screenings. They even went so far as to impound the model rockets used in it, considering them too dangerously informative for general access.

This is hardly the place for a moral examination of Operation Paperclip, even if I was qualified to undertake it…but there is no getting away from the uncomfortable realities behind the scientific research that finally would send a rocket to the moon. Wernher von Braun may be the best-known of the NASA scientists who earlier, willingly or not, exercised their skills for the Nazis, but he was not the only one: among the rest we find Hermann Oberth.

Towards the end of WWII, Oberth and his family were living in what would become part of the American Zone of occupied Germany. Whether with definite future ideas or not, in 1948 the Americans allowed Oberth to relocate to Switzerland. In 1955, he joined von Braun, one of his earliest disciples, at NASA: their work together would produce the Saturn V rocket.

It is difficult to reconcile these two visions of Hermann Oberth—and even more so when we add to the equation the pop-culture version of him that emerged in the 1920s: the scientific outcast who did indeed go on to prove the fools wrong. There’s certainly no easy answer to how we’re “supposed” to feel about any of this.

(Me? – I cheat: I figure if Star Trek can cut Oberth some slack, so can I.)

So for the moment let’s just focus on Oberth’s role in the development in that rare but fascinating branch of the science-fiction film that deals with established science and the rational extrapolation from it. Monsters and madmen may be more fun, but there is an intellectual thrill to the hard-science film that is hard to beat, and which is even greater with hindsight—in the realisation of what certain brilliant individuals could conceive years and even decades before it even began to become reality.

We are experiencing at the moment a slightly strange but very welcome proliferation of what we can still call “space-flight films”, every one of which can ultimately be traced back to Woman In The Moon. If Oberth’s writings had inspired a generation of scientists, the film to which he lent his vision inspired—well, not a generation, but a handful of later film-makers who sought to add the knowledge of their own time to his proven theories, while envisaging a soaring future.

We should note here that though the line between Woman In The Moon and Destination Moon now seems straight, and in some ways certainly is – and though it would be many years after the event before Western science-fiction fans would realise it – the space-flight film took an interesting detour through the Soviet Union between the 1930s and the 1950s: before, that is, Soviet scientists put a figurative rocket up the American tail-pipe on the 4th October 1957.

As always, the reality was preceded by the vision, with film-makers paving the way by turning into a form of reality the wondrous possibilities of scientific theory.

.

Footnote: This may have been the first serious space-flight film, but it wasn’t the first science-fiction film to dabble in hard science. Twenty years earlier, the British film-maker, Walter R. Booth, imagined aerial warfare with equally eerie prescience; the esteemed El Santo has more on that subject.

♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦

This review is for Part 3 of the B-Masters’ 20th anniversary celebration!

Lovely piece of work here. Something occurred to me during my reading of this, which was your rather scientific approach to the relationships in the movie. I’m sure I’ve noticed it before, but it kind of crystallized for me here why I enjoy you discussing them almost as much as I do your discussing the science in movies. Namely, it’s a unique way to look at them, and it offers interesting insights.

By the way, I didn’t notice any issues with the images being too dark.

LikeLike

Thank you, my dear!

Uh, yeah: it’s my scientific approach to relationships that keeps me from having any. 😀

So often I find myself tearing my hair over what is obviously a man’s idea of a “proper” relationship; yet here we have a weird sort of gender equality, with a woman responsible for one every bit as exasperating!

Thanks for the feedback on the images. It’s often frustrating trying to capture black-and-white films properly, either they come out too dark or over-bleachy.

LikeLike

“Alone – as alone as any man has ever been – Helius turns towards his base-camp…

…where he has a surprise waiting for him.”

Well why the review makes it clear what the surprise was, my sense of humor immediately filled in here: Josephine had stayed behind to keep him company! The Mouse in the Moon?

LikeLike

Ha! – so THAT’S where that idea came from! 😀

Josephine’s fate is left as undetermined as the others’, but I guess we can say that if anyone makes it back to Earth, she will too (presumably to be adopted by Gustav).

LikeLike

A great review, but a couple of your hangars turned into “hangers”.

LikeLike

Of course they did…

Yes, I’ve spent the morning during my usual post-posting-frenzy typo-sweep, hopefully I’ve caught ’em all. 🙂

LikeLike

Sorry, you missed one: ““Science fiction” is such an all-embracing term that it is often found necessary to break it up into subcategories—the most telling of which may be “hard” and “soft”. While the latter can encompass almost anything, much greater demands are placed upon the latter:” I’m pretty sure that last “latter” is meant to be “former”. 😉

LikeLike

Crap.

Thank you. 🙂

LikeLike

I think you mean “the latter” and “the former”; you have “the latter” twice.

Still! Really interesting review. I only recently discovered the relocated site, and have been catching up.

LikeLike

…And I see someone else beat me to it.

LikeLike

😀

Never mind, always grateful for that kind of heads-up. Glad you’ve found me again!

LikeLike

Seeing as you’ve pretty much run out of real B-movies you genuinely want to watch, might I suggest the 1978 BBC sitcom “Come Back Mrs. Noah”? British sitcoms usually have six half-hour episodes per season, and since this notorious example of what-were-they-thinking? was cancelled after one season, its total running-time is a manageable three hours, and you only have to buy one DVD.

Set in the year 2050, it concerns the misadventures of the first cleaning woman in space, who becomes an accidental astronaut as a result of a premature rocket launch. Much hilarity ensues, mainly because the proper astronauts are even worse at it than she is. Mrs. Noah was played by Mollie Sugden, an actress remembered solely for being a core cast-member in the long-running sitcom “Are You Being Served?”, in which her character’s trademark was to constantly talk about her pussy. She was of course referring to her cat, but since the show was set in a department store and the cat never appeared on screen, there were double entendres aplenty. How we laughed.

Another even more obscure and even more peculiar failed British sitcom is “Kinvig” from 1981, which lasted for seven episodes before its inevitable cancellation, and is also available on DVD. It was written by, of all people, Nigel “Quatermass” Kneale, and it parodies UFO contactees and flying saucer cults of the “space brother” variety, especially the Aetherius Society, by having its very ordinary but somewhat fantasy-prone hero become involved with incredibly clichéd space aliens who somehow need his help to save the universe or whatever. It’s never made entirely clear whether or not the aliens are real, so our hero may, like Don Quixote, have crossed the line from day-dreaming a little too much to having a serious mental illness. How we laughed.

And finally, an actual B-movie I don’t think you’ve done yet, the 1984 “Star Wars” parody “Hyperspace”, also known as “Gremloids”. If you can find an affordable copy, this very minor sci-fi spoof is notable mainly because its villain, Lord Buckethead, has been sporadically active in real-life British politics as the leader and sole parliamentary candidate of the Gremloids Party, and remains so to this day, recently getting twice as many votes as the Official Monster Raving Loony Party candidate. He appears to be immune to the passage of time, possibly helped by the fact that when you’ve got a bucket on your head it’s very difficult for other people to tell whether you’re the same person who wore the bucket 35 years ago. Doubtless in the impending election he’ll be standing in the constituency of our current Prime Minister so I won’t be able to vote for him. Which is a shame, because of all the current contenders for the top job, a fictional character with a bucket on his head is clearly the least worst. And at least he’s honest about being a ruthless madman whose ultimate aim is to conquer the galaxy.

LikeLiked by 1 person

you’ve pretty much run out of real B-movies you genuinely want to watch

Ummm…okay. Not sure where you got that?? 😀

Psst: this really should be in ‘General chatter’…

Recommendations noted, tho’.

Weirdly enough I know the real-life Lord Buckethead but did not know where he came from, so thanks for that!

LikeLike

“we get the impression here that Helius’ construction of his rocket was undertaken mostly as a theoretical exercise, just to see if it could be done”

Man, shareholders in German companies were pretty damn live and let live back in the day! I’m picturing you picturing Helius trying to explain the line items in his grant application instead and tearing your hair out…

LikeLike

😀

What worldwide Depression? – Helius is apparently stinking rich enough not even to have shareholders.

I’m now envisaging an alternative ending: “Don’t worry, Friede, I’m sure they’ll be back for us in no time. After all, it’s the 28th October 1929 and there’s oodles of money to throw at projects like this!”

LikeLiked by 1 person

Heinlein’s “Man Who Sold the Moon” involves the protagonist raising investments and interest for his moon trip by starting a rumor that moondust is full of diamonds. A rumor which incidentally ends up being true. So yeah, I have to imagine Heinlein saw this movie and drew inspiration.

LikeLike

I don’t doubt that at all. It’s fascinating to note the comparisons and differences.

LikeLike

Excellent. Thank you for this.

LikeLike

Thank you. 🙂

LikeLike