“Eight dead. Fifteen minutes ago they were still alive. A couple of hours ago they were hurrying along streets, saying goodbye to friends and family; even arguing…”

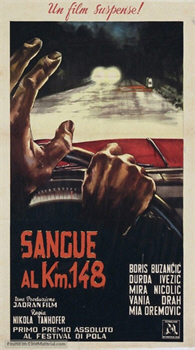

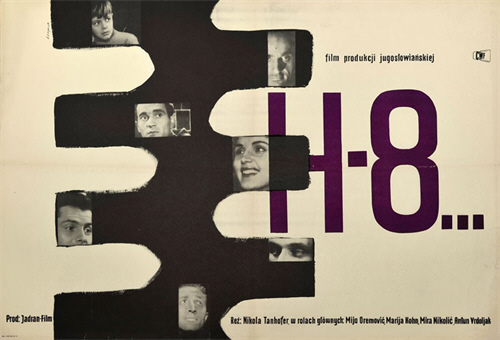

Director: Nikola Tanhofer

Starring: Boris Buzančić, Antun Vrdoljak, Đurđa Ivezić, Ivan Šubić, Stane Sever, Andro Lušičić, Josip Presl , Vanja Drach, Ljubica Jović, Drago Mitrović, Marijan Lovrić, Siniša Knaflec, Mira Nikolić, Dobrila Berković, Mia Oremović, Rudolf Kukić, Pero Kvrgić, Marija Kohn, Nela Eržišnik, Antun Nalis, Fabijan Šovagović, Pavle Bogdanović, Milan Orlović

Screenplay: Zvonimir Berković and Tomislav Butorac, based upon a story by Nikola Tanhofer and Zvonimir Berković

Synopsis: On a rainy highway, a truck and a bus travelling in opposite directions draw ever closer to disaster… Some two hours earlier, passengers board a bus in Zagreb, bound for Belgrade. The elderly Professor Nikola Tomašić (Stjepan Jurčević) and his wife (Krunoslava Ebrić-Frlić) board together; as do the actor Krešo (Vanja Drach) and his wife (Ljubica Jović). However, others are forced to separate. A young mother (Mira Nikolić) must travel by bus with her baby in her arms, as she and her husband can only afford a motorcycle. Civil servant Ivan Vuković (Drago Mitrović) is seen off warmly by his wife and two young sons; while the parting of Mr (Pero Kvrgić) and Mrs Jakupec (Marija Kohn) from the former’s sister, Gospodina (Nela Eržišnik), with whom they spent a very tense holiday, is full of false protestations of affection. The seal is set on the Jakupecs’ miserable vacation when their daughter, Vesna (Dobrila Berković), trips and bloodies her nose while getting on the bus. Alma Novak (Đurđa Ivezić), an aspiring concert pianist, is leaving Zagreb altogether—and breaking off with the man who has been both her mentor and her lover. Dr Šestan (Andro Lušičić) tells his wife that it is best if he takes their young son, Neven (Josip Presl), away for a while; he is confirmed in this decision when a newspaper vendor begins shouting the headlines… As the bus pulls out, a young journalist (Antun Vrdoljak) races after it and just manages to swing himself on board. He pushes to the front of the bus where he settles next to his colleague, Boris (Boris Buzančić); although not without noticing the beautiful Mrs Svicarcev (Mia Oremović)…nor without her jealous Swiss husband (Rudolf Kukić) noticing his notice… On the first stage of the journey to Belgrade, the bus is under the control of driver Josip Barač (Ivan Šubić), who touches the good-luck charm dangling from his rear-view mirror as he begins the journey. Also on board is alternate driver, Janez Pongrac (Stane Sever), a more senior driver who has suffered demotion due to violations of company protocol. Meanwhile, a truck driven by Rudolf Knez (Marijan Lovrić) pulls out of Belgrade, carrying a load of sheet metal bound for Zagreb. Travelling with Knez is his young son, Vladimir (Siniša Knaflec)…

Comments: Ordinarily I probably wouldn’t consider H-8… suitable material for review, for the simple reason that it is a true story.

Of course, H-8… isn’t the only such film to borrow its plot from a real-life event. The same year’s Crash Landing does exactly that—but differs significantly in that no-one died in its chosen incident. This film also somewhat prefigures 1960’s The Crowded Sky, in which most of the running-time is just build-up to the brief disaster; while in structure, it very much resembles the next disaster-movie proper I’ll likely be dealing with—both of them adhering, via use of the extended flashback, to my personal disaster-movie credo, Crash it in the first twenty minutes or don’t crash it at all.

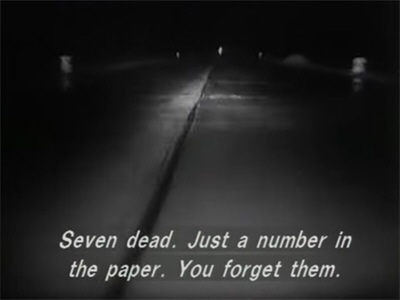

The difference here is that H-8… is not only based upon a real incident, it tells us – and shows us – so insistently from its first moments; its point is that people died. Furthermore, the nature of that incident means that no part of the film deals with the management of the situation, either before or after, which is such a crucial element of most disaster movies. The crash happens, and that’s that. People die, and that’s that.

It is therefore impossible to approach this film with the usual facetious attitude; nor can we be so careless (not to say ruthless) in our attitudes towards the characters.

Ultimately, however, the decision to subject H-8… to review came down to the circumstances of the film’s production: the sheer unlikelihood of discovering the disaster-movie formula in a black-and-white Yugoslavian drama of 1958.

While I say “formula”, it is far more likely that this was, rather, a case of parallel evolution. Disaster movies per se were only just getting established in America and Britain when H-8… was made, and it does not seem that any of the films we might consider its model had been screened in the former Yugoslavia.

(On that point, the film was Yugoslavian at the time of its production. I understand that H-8… is now considered Croatian. I hope I have that right.)

While he was already known as a cinematographer, and would go on to have a significant impact upon Eastern European cinema as a screenwriter, a director and a teacher, H-8… was only the second film by Nikola Tanhofer. His first, made the year before, Nije bilo uzalud (It Was Not In Vain), a strange, almost-horror film about a young doctor fighting sinister forces in a small village, was well-received; but from the beginning H-8… achieved significant critical and popular success.

Some of this may be attributed to the fact that – unlike the vast majority of local films at the time – H-8… dealt neither with the war nor with contemporary politics, a difference embraced by film-goers. In addition, the film’s experimental approach was recognised as something new and refreshing, while its trick-photography and model-work had not been attempted before in Yugoslavian cinema. Fresh memories of the tragic incident upon which it was based also gave the film a serious appeal. H-8… went on to win the top prize at the 1958 Pula Film Festival, and is now considered one of the best-ever Croatian films.

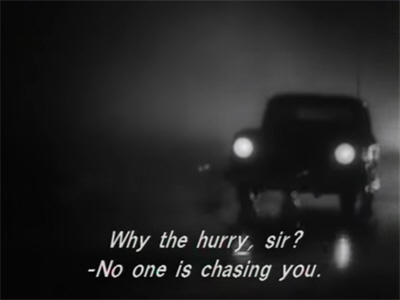

The incident upon which H-8… is based occurred (as the film tells us starkly at the beginning) at 8.33 pm on the 14th April 1957, 148 km along the road between Zagreb and Belgrade. In attempting to overtake a bus, a car ran a stretch of road directly towards a truck hauling sheet metal. Blinded by the headlights, the truck driver swerved to avoid the car and in so doing, pulled into the path of the oncoming bus. Seven people died on impact, an eighth shortly afterwards.

The car, meanwhile, escaped unscathed; and not only did the driver not stop, he or she (the film assumes it was a man) turned out their lights, so that their license plate could not be observed. Witnesses were able to give only the make of the car and the beginning of its license number: H-8…

All that was later established of the lead-up to the crash – where the vehicles came from, at what speeds they were travelling, what conditions were like, who was where, when – is presented at the outset of the film with documentary-like precision, albeit in a tone of rising hysteria. What may or may not have been contributing factors, such as the truck driver having some wine with his dinner, are also scrupulously presented.

The opening sequence of H-8… is powerful and disturbing. It is notable for the escalating tempo of the lead-up to the accident and the flash-cut montage by which the crash is conveyed. (The film was edited by Radojka Ivančević, shortly to become Radojka Tanhofer.)

This opening also builds suspense by withholding most of the information as to the identity of the crash victims. It does tell us that of those on the bus, one of the two drivers will survive and the other will not; and we know from the opening footage that the elder man, who was driving at the time, is the survivor. It also tells us that one of the crash victims is a child…

However, H-8… gets its greatest effect from how it makes its further revelation: it tells us only that in addition to one of the drivers, the bus passengers occupying the seats numbered 2, 3, 4 and 5 were killed. (In fact, there is one more bus victim not in a numbered seat, but we don’t know that until right at the end.) We know who occupies those seats at the outset; but throughout the film, the passengers keep moving around. Thus the whole thing plays out as a deadly sort of game, musical chairs meets Russian roulette, as the crash draws nearer and nearer…

But while all of this is presented as accurately as possible, no-one knows in detail what transpired on the bus and the truck prior to the accident; and this is where the disaster-movie formula kicks in. The drivers and their passengers all get their own subplots, some of which are based on testimony, but most of which were invented for the purposes of the film. There are no flashbacks here, which is another thing that pushes H-8… towards the “drama” end of the spectrum; but otherwise the film gives us exactly what we’ve since been taught to expect: soap, and plenty of it.

When I say there are no flashbacks in H-8…, I mean that there are no individual, back-story ones. After its stark, disturbing opening, the entire story is told in one long flashback. The film proper opens with the bus passengers gathering and boarding in Zagreb some two hours before the fatal incident.

The overarching theme here is separation. We visit briefly with a young woman who seems to be breaking off a relationship with an older man. A young mother, baby in arms, waves and blow kisses to her husband, who will travel the same road by motorcycle: the couple cannot afford a car.

Ivan Vuković, a civil servant, is seen off by his wife and two young sons. At the last minute, the boys give him a sealed letter marked, “To be opened at 8.15 pm.”

Less heartfelt are the goodbyes between Mr and Mrs Jakupec and the former’s sister, with whom they have been staying, as their children pull faces and spit at one another. The boy’s mother tries to force him to kiss his cousin goodbye, but he retaliates by pointing out that she called the girl “an idiot”, which provokes both a slap and much embarrassed protestation.

Dr Šestan is travelling with his young son, Neven. As he parts from his wife, he reacts badly when a newspaper seller tries to force upon them a copy of the Zagreb Evening Post. His wife quietly reassures him that the case won’t yet be in the papers; but even as she speaks, the news vendor can be heard calling the headlines: “Doctor scandal in children’s clinic…!” This, the doctor says to his wife, is why he needs to take the boy away.

The bus’s two alternating drivers board last: Josip Barač, the younger of the two, takes the first stage of the journey; Janez Pongrac, the elder, will take the wheel after the bus’s first scheduled stop.

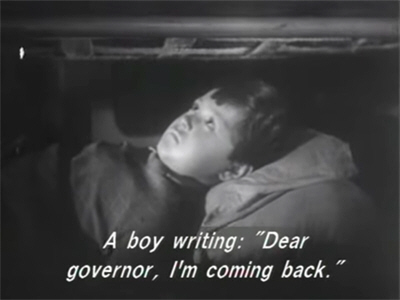

Meanwhile, we meet the truckdriver, Rudolf Knez, who also has a passenger: his young son, Vladimir. There is a bit of ominous background filled in for the latter which mentions a boys’ home, failed grades, and absences; but as it turns out, the inference we draw from this is probably the wrong one.

Back in Zagreb, as the bus begins to pull out, a young man comes racing towards it and just manages to swing himself onboard. As he catches his breath, the film’s narrator informs us that he holds the ticket for seat #3…

The young man is a court-reporter for a newspaper. He drops into the seat next to his colleague, Boris. We learn that he has been covering the case in which Dr Šestan is involved.

(I should note here that we do not find out that Boris is called Boris until six minutes before the end of the film; and his friend never gets a name at all, despite his significant role. I will refer to him as “the reporter”.)

As he got on, the reporter was very much struck by a beautiful woman. As he is putting away his coat and getting settled, he directs another long look from his seat at the front of the bus to hers at the back. Her husband, an older, German-speaking man, notices this scrutiny immediately and remarks upon it. Mrs Svicarcev merely looks smug.

Meanwhile, the young mother will be the first to be bothered by an officious middle-aged man who will force his company on a number of different people over the course of the journey. He’s the type who is always quite convinced of his own wit and charm. He gives us a sample of it here by suggesting to the young woman that, having let her husband go off on his motorcycle, that’s the last she’ll see of him.

On the truck, a conversation between Knez and Vladimir reveals that the boy was in a home not because of his own misdeeds, but because his mother is dead and his father was in jail. This created a double difficulty for Vladimir, in that nearly all of the home’s other inmates had been respectably orphaned during the war. Knez has only just reclaimed custody of his son, and is now determined to stay on the straight and narrow for his sake.

Children also occupy the mind of a young army corporal on the bus, Mišo Petrović, who has received a leave of absence to see his wife and newborn son. He reads over and over again the telegram that called him home. The soldier in turn has caught the eye of Mrs Tomašić, whose own son is also in the army and is about the same age. Perhaps they even know each other? She tries to talk to her husband about their boy, but he is focused upon his own work. The Professor has written a book on the origins – and corruptions – of the Croatian language, and he is travelling to Belgrade in the hope of getting it published. (The misuse of their mother tongue by those around him will cause the professor ongoing agonies.)

Up-front, Boris and the reporter have been eyeing Alma Novak through the crack between their seats. It’s a familiar scenario: a brash, rather cocky young man pushing his shyer friend on a woman armed with his own pick-up lines. Of course, the reporter thinks, “Haven’t we met before?” is a “witty” opening gambit; but though he recognises his friend’s lines for the rubbish they are, Boris can’t come up with one of his own. His efforts are so feeble as to win a reluctant smile from Alma; but this is wiped from her face when he asks if the man seeing her off was her father?

Meanwhile, Janez Pongrac is punching tickets. He gets into a dispute with a man called Krešo, for whom making scenes with himself at their centre seems to be his hobby. (Krešo’s wife, after a futile tugging of his sleeve, turns away with a, Oh God here we go again gesture.) It turns out that Krešo didn’t bother to buy the tickets; his embarrassed wife covers the cost with an apologetic look at Pongrac.

Krešo’s voice, when he raised it, was strangely hoarse. This is noticed by young Neven Šestan, who brings it to the attention of his doctor-father. Neven also asks him to borrow the children’s page from the newspaper being read by Officious Man, but Dr Šestan insists it isn’t nice to borrow…

Up the back, the Jakupecs are still trying to prevent Vesna’s bloody nose from messing up the seats. Mrs Jakupec is also getting a load off her chest, after her “holiday” was spent being treated like a servant by her condescending sister-in-law. Why couldn’t they go somewhere where she could be waited on…?

H-8… is interrupted by its narrator whenever an established event in the timeline takes place. This is, in its way, the most painful aspect of the film, since we are repeatedly reminded that – as with nearly any disaster – it was all a matter of appallingly unlucky timing, and that had any one of the three vehicles done something only fractionally different, the crash probably wouldn’t have happened.

The first of these moments, after the departure of the two vehicles, is the truck pulling into a service station in Slavonski Brod (a city which is now in eastern Croatia, near the border with Bosnia and Herzegovina). “It was 7.20 pm,” the narrator observes. There, Knez and Vladimir have something to eat: their first supper together since their reunion. The former has some wine, as has already been brought to our attention. But this is not the most significant thing that happens, which is Knez falling in with an acquaintance from his criminal days, to whom he reluctantly ends up giving a lift (and who drinks most of the small carafe of wine).

This acquaintance, whose name is Franjo Rosić, becomes like a tormenting devil to Knez—describing to him all the ways in which a truckdriver can make a very comfortable living; helping to rip off construction sites, for example…

Slavonski Brod is also the Krešos’ destination. We gather that they are newly married; that they are so because Mrs Krešo is pregnant; and that they’re broke, and on their way to the home of Mr Krešo Sr. Slowly it emerges that Krešo is not an amateur self-dramatist at all, but a professional actor—and one whose career may have been ended less by a throat complaint than the backfiring of the medical treatment to which he was subjected, which has left him with permanent laryngitis and subject to painful coughing fits. The situation has made him less than fond of doctors…

On the bus, Boris has sensibly given up “lines” for simple conversation. This takes a new and more intimate turn when Alma’s attention is caught by a piece of music on the radio, which features her own music professor playing piano with the Philharmonic. This leads to various revelations including that the man at the bus station – “Old enough to be your father,” in Boris’s opinion – was her professor; also her lover. She has just broken with him…

Meanwhile, the reporter is wandering up the bus. He confirms his suspicion that it is indeed Dr Šestan; shares a joke with the young soldier; starts an eye-flirtation with Mrs Svicarcev; and finally has a stab at the young mother – “Haven’t we met before?” – who is properly unimpressed.

However, she finally lets him hold the baby, which is more than Mr Officious got. He retaliates with a jeer about “modern parents”, which sets her off like a firecracker. Indignantly, she spells out the various ways in which she and her husband are taking sensible, self-denying steps to settle themselves and their baby; adding that if they do have to go on living in their separate rented rooms for now, well, they can nearly afford an apartment.

She gives a reluctant laugh, though, when the reporter and Mr Officious air their bemusement over where exactly, under those circumstances, the baby came from.

Things are less amusing further up front, where Mrs Krešo is overcome by nausea. Over her objections, Krešo insists that the bus be stopped so that she can get some air. (So that she doesn’t throw up on the bus would be a more cogent argument, methinks.) Barač inquires for a doctor, and Dr Šestan steps outside to see if he can help. He finds only normal pregnancy symptoms, though, which prompts a sneering reaction:

Krešo: “A wise man said that doctors are fortunate. Their successes praise them, their mistakes are buried.”

Everyone then climbs back on. The matter hasn’t held up the bus for too long; only for three minutes…

On the truck, Rosić and Vladimir have swapped spots, with the boy tucked into the cabin-bed. He is nevertheless awake and fully alert to Rosić’s evil influence. He does his best to hold his father to his resolutions—talking about his mother, and his new school in Zagreb.

Back on the bus, Alma and Boris are getting along well enough to have an argument over the merits of popular music. The reporter and Mr Officious are forced to turn their backs while the young mother breastfeeds her baby, which gives them an excellent view of Mrs Svicarcev’s legs as she stretches them provocatively into the aisle.

We learn that she and her husband are on the bus in the first place because she wrote off their car; although he agrees placatingly that it wasn’t her fault. The two are speaking German; Mr Svicarcev does not understand Croatian, which opens up possibilities for his wife. She rises, and he helps her on with her fur coat—under the envious eyes of Mrs Jakupec, who speaks bitterly of her husband’s refusal to buy on credit.

The bus makes its second official stop. Not all of the passengers get out, some of them dozing in their seats, and one who does not is an individual who has been behaving suspiciously from the outset, paying far too much attention to the possessions of the rest and particularly to the top-of-the-range camera owned by the reporter. The latter turns up in time to retrieve his possessions, though, and the thief is forced to find other marks.

Inside, it is confirmed for us that Pongrac is strictly on the wagon after drinking on the job led to his demotion; in fact, he’s just back at work after six months drying out. Barač has a glass, though; and it is made clear that this is not unusual. The reporter makes ground with Mrs Svicarcev, while Boris blows it with Alma by stupidly following his friend’s advice and trying to force a kiss on her.

There is a brief but ugly scene between Dr Šestan and Krešo, but the latter’s sneering dip into Hamlet only serves to remind him that his career is probably over. As it happens, Šestan remembers the case and understands Krešo’s attitude towards doctors; also, as he explains to the puzzled Neven, that his obnoxious behaviour is a way of “pre-empting pity”.

As Barač gives a two-minute warning, we see that the thief has succeeded in lifting someone’s wallet. Deciding that discretion is the better part of valour, he then deliberately misses the bus.

“This man should have been the first to die,” comments the narrator; but he is not speaking in terms of karma: “He had seat #2; that seat is now unoccupied…”

“Seats #3 and #4 are still unoccupied,” he adds. These are the seats held by Boris and the reporter, who are pursuing their interests elsewhere. Boris is sitting next to Alma, although they’re not speaking; the reporter, still buzzing around Mrs Svicarcev and taking advantage of Mr Svicarcev’s incomprehension by loading his suggestive Croatian conversation with smiles and friendly gestures.

At one point Mr Svicarcev thinks he is quoting poetry and asks for a translation of it, which is declined:

The reporter: “Translations are like women: if they’re faithful, they’re not beautiful; and if they’re beautiful, they’re not faithful.”

Outside, the predicted rain-storm begins…

With Pongrac driving the bus, Barač checks whether any new passengers got on at the last stop. They didn’t; but he takes pity on Vesna Jakupec, whose nose has started bleeding again after her father made her wipe it. He carries her away to the front of the bus, claiming that it is “an easier ride” up there, but really, we suspect, to separate from her miserable, bickering parents.

As they look on, the Jakupecs quietly discuss their daughter; and we learn that her aunt’s cruel dismissal of her as “an idiot” stemmed from the fact Vesna is indeed a bit “slow”. She tries hard, Mrs Jakupec concedes, but she is incapable of remembering anything; and she can’t make friends. As Mrs Jakupec confesses to sometimes beating the child out of frustration, Mr Jakupec comments that it would have been better if they’d never had her…

We notice, though, that Barač doesn’t have any trouble communicating with Vesna. Taking her on his knee, he tells her about his family. Vesna is rather dazzled at the thought of a father whose children aren’t afraid of him, and who plays with them, and helps with their homework. She is also taken by “Tihomir”, the little doll-figure that is Barač’s good-luck charm: a gift from his children. He encourages Vesna to touch it, promising her that her wish will come true. Her wish is simply that her nose would stop bleeding…

On the truck, Rosić is still tempting Knez with the promise of easy money, going on and on about the simplicity of his plan, and conversely how hard and unrewarding is a life of honesty; and it is because he is so tempted that Knez becomes furious—suddenly bringing the truck to a screeching halt and ordering Rosić out.

They’re in the middle of nowhere, and it is by now pouring rain; and, we were told at the outset, this action violates the code of the road; but it is only at Vladimir’s behest that Knez stops and lets Rosić back in again.

While Professor Tomašić reconsiders his life’s work in light of a comprehensive dismissal of it by Boris (who he was unwise enough to approach in the wake his blow-up with Alma), Krešo avoids telling his wife “what he’s thinking about” by reading to her from the paper—and almost the first thing he comes across is the story of the scandal at Dr Šestan’s clinic. Rather more than a mere “scandal”, in fact: four children died after botched blood transfusions.

In the seat behind, Dr Šestan does not wait for the inevitable revelation: he sends Neven up to the front of the bus, to sit with Vesna…who he promptly diagnoses with haemophilia. The terrified girl flees back to her parents, and Neven to his father, who quietly reminds him that only men can have the condition. Neven concedes this, but asks his father to see Vesna anyway, as her nosebleed won’t stop.

This gives Krešo – to whom the newspaper story is as manna from heaven – his cue: he swings around in his seat and makes everyone on the bus privy to Šestan’s situation. Poor Neven is overwhelmed by horror and distress, as his father-hero is torn down in front of him.

We’ve been waiting for this since the start of the film; but there’s a punchline to this subplot, which is that the reported inquiry was to determine which of the possible staff members was responsible, and that Dr Šestan was subsequently exonerated of all culpability…only that isn’t going to be in the papers until tomorrow (at which point, we presume, the verdict will be overshadowed by quite a different story).

The reporter intervenes here, and so he should: it was he who wrote that first story—in which, we gather, he jumped to what he now knows were some false and damaging conclusions.

The niceties of the conversation are, literally and figuratively, over Neven’s head. He has been reading the reporter’s first effusion, and now runs from his father to find a refuge up front.

Krešo is rather pleased with this outcome: “I love seeing our young lose their innocence.”

“The bus was now at the 140 km mark,” observes the narrator. “If the crash had happened now, fewer would have died. Three seats intended for victims were still empty…”

It is 8.10 pm. The young mother, having opened her window to throw out a sandwich wrapper, can’t get it closed again and decides to change her seat. Petrović offers her his—and moves to the front of the bus. Mrs Tomašić, as always listening patiently to her husband, gives in to temptation and steps across to speak to the young soldier. The Professor tells her not to bother him, but Petrović insists it is no bother at all—and moves across to allow her to take the aisle seat…

8.15 pm. Ivan Vuković has so far obeyed his children and not opened the envelope, in spite of the urging of Mr Officious, but now he tears it open, finding inside a note instructing him to ask the driver to turn up the radio. Vuković then hears his own name: his children have sent him a musical dedication to wish him a pleasant journey. Both to hear better, and to get away from Mr Officious, he moves forward and takes the last seat…

“I wish you Godspeed and farewell,” warbles the singer.

8.32 pm, 147 km from Zagreb.

A car pulls up close behind the bus, its headlights drawing the attention of the Jakupecs in the back row…

“In eighteen seconds,” says the narrator, “the following will no longer be alive…”

H-8… is a film impossible to just enjoy. It is far too insistent upon the details of the crash, and the cruel randomness of the whole thing; upon the damaged and ruined lives even of those who survived. That’s another of the differences between this and a real disaster movie: we get the pathos, but none of the karmic balancing we associate with this sort of thing. We aren’t even thrown the usual sop of, say, Dr Šestan saving the life of Krešo or Mrs Krešo. All we’re left with is the brutal reality of cosmic injustice.

In this respect, too, we must deal with H-8…’s disturbing insistence upon the particular vulnerability of children. There is no cinematic dispensation here, to keep them safe. One child is killed; others are orphaned. The dangers which threaten the young have, we see, by no means lessened with the end of the war, merely changed their nature.

The framework of this film makes it somewhat easier than it otherwise would be to deal with what I called at the outset “the soap”, which constitutes the bulk of the screenplay and runs all-but uninterrupted between the bookending crash scenes. Truthfully, this sometimes gets a bit tedious; but then, the ordinariness of the characters is the point; and our knowledge of what waits for them gives a natural poignancy to their interactions. There are a few foreshadowing touches along the way, but on the whole the screenplay by Zvonimir Berković and Tomislav Butorac avoids heavy-handedness.

Likewise, the acting in H-8… is low-key and effective; it is the characterisations that occasionally jar, not the actors. They may not be familiar to western eyes, but many of the cast had lengthy careers. Top-billed Boris Buzančić also had a secondary one in politics; while Đurđa Ivezić became a cartoon voice-actress—including dubbing Betty Rubble and Smurfette!

But unless I’m much mistaken (and apologies to both if I am), the most interesting alternative career is that of Dobrila Berković, who plays Vesna, and who is now, as Dobrila Berković-Madgalenic, a celebrated cellist and music instructor. H-8… was her only film—which brings me the point that I really wanted to make here, that the performances from its child actors are among the film’s best. All three of them have an engaging natural quality, while Siniša Knaflec succeeds in making Vladimir sympathetic and appealing, without being the least bit “cute”. And yet of the three, only the latter made more than this one film.

H-8… put Nikola Tanhofer on the cinematic map in 1958; but despite eventually building an impressive body of work, he is not as well-known today as some of his contemporaries. It has been suggested that this is because Tanhofer never settled into a single style, but instead continued to experiment with genres and techniques.

If difficult, H-8… is also a remarkable film in many ways; not least if we consider that nothing remotely like it had been attempted before in Eastern Europe (and had only occasionally done so outside it). It is a thoroughly humanist film, hurting for the characters and deeply angry with the driver of the car—to whom the film is, with heavy sarcasm, “dedicated”; not so much for the recklessness that caused the crash, as for the cowardice shown afterwards. It is this sense of empathy, shot through as it with an aching awareness of the unfairness of life, that places H-8… in an entirely different category from the films it superficially resembles.

♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦

This review is part of Part 4 of the B-Masters’ 20th anniversary celebration!

Fascinating. For a more conventional technical disaster film, like The Poseidon Adventure or the Airports, the ongoing disaster itself is often interesting enough that I find the efforts to humanise the characters superfluous and distracting; here, I think your final photo makes the point, that seeing “seven dead in road accident” is just a random bit of news, but each of them was a distinct person and the protagonist of their own story.

LikeLike

Yes, that’s exactly right. This seems at first glance to be following the same pattern but it’s actually the flip-side of the formula we’re familiar with.

It also occurred to me that this wouldn’t work at all with a different kind of disaster. You couldn’t substitute a plane, for example. This works not just because it’s true, but because somebody caused this—and it is that rather than the disaster per se that drives the narrative.

LikeLike

One wonders whether Mr. H8 driver ever saw the movie.

LikeLike

I would think the H8 driver would have made a point of NOT seeing this movie.

LikeLike

He or she may not have seen it, but I doubt they could have avoided hearing about it.

We always like to think that people who do terrible things and get away with it are punished by their conscience afterwards but if you watch as much true crime stuff as I do you know that some people have a terrifying capacity to just shrug and move on.

(Not me, I add resentfully: OCD brain means I fret over petty stuff from decades ago. 😦 )

LikeLike

Yeah, I have that problem, too- stay awake all night with my conscience bothering me about something I’m pretty sure no one else has any recollection of at all. Meanwhile, there are people who have no problem doing truly horrible things all the time (and many of them are running my country now), and never seem bothered by it at all.

LikeLike

People are indeed very good at shrugging off what they’ve done. I cringe when I hear someone say “At the end, people regret the things they didn’t do, not the things they did do” as if all that means is an exhortation to have fun and enjoy life, like “Nobody ever said on their deathbed that they wish they’d spent more time at the office.” It’s certainly true that people mostly regret what they didn’t do, but that just highlights how oblivious people are to their own misdeeds.

LikeLike

Excellent review. Thank you so much.

I was quite touched by the song at the end.

LikeLike