“You’re blind…and you can’t speak…but you can hear…and that will never do…”

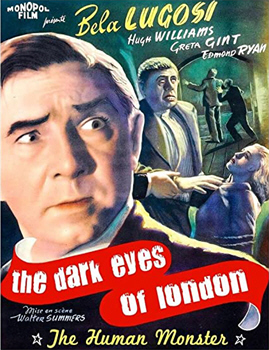

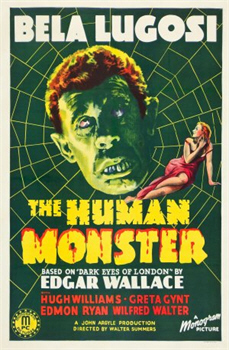

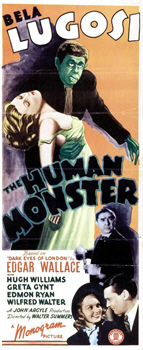

[Also known as: The Human Monster]

Director: Walter Summers

Starring: Bela Lugosi, Hugh Williams, Greta Gynt, Edmon Ryan, Wilfred Walter, Alexander Field, Arthur E. Owen, Gerald Pring, George Street, Bryan Herbert, May Hallatt, O. B. Clarence

Screenplay: Patrick Kirwan, Walter Summers, John F. Argyle and Jan Van Lusil, based upon the novel by Edgar Wallace

Synopsis: After a wave of drowning deaths involving people carrying significant insurance, Scotland Yard begins to investigate. Detective Inspector Larry Holt (Hugh Williams) reports to his superiors that a forger named Fred Grogan (Alexander Field), extradited from the United States, will be arriving in two days under escort. At the office of the Greenwich Insurance Company, the head of the company, Dr Feodor Orloff (Bela Lugosi), writes out a cheque for two thousand pounds, a loan for a man called Henry Stuart (Gerald Pring), who assures Orloff that he will be paid back as soon as an invention of his is purchased by the government, and that he is willing to sign any kind of bond. The conversation then turns to Orloff’s support of a home for the destitute blind, which is run by a Mr Dearborn, himself a blind man. Orloff tells Stuart that if he really wishes to express his gratitude for the loan, he should make a donation—or better yet, pay the Home a visit. He reinforces this suggestion with a hard look into Stuart’s eyes, and the flat statement that he will visit the Home, the following evening… As soon as Stuart has gone, Orloff summons his secretary and orders that when Grogan has his court appearance, his bail is to be paid; he also gives her an advertisement to be placed in the newspapers. Orloff then prepares a message in Braille and, having wrapped the strip of paper around a coin, throws it from a window to where a blind and dumb man named Lou (Arthur E. Owen) plays the violin on the street to support himself. Lou collects the message, and moves off down the street… Inspector Holt calls upon Orloff, explaining that a number of insurance companies are under investigation. Holt asks to see the policies of two of the drowning victims, noting the beneficiaries. That evening, Lou makes his way to Dearborn’s Home for the Destitute Blind, where he is greeted warmly by Jake (Wilfred Walter), a hulking individual with a disfigured face. Lou gives the Braille message from Orloff to Jake, who nods his understanding and makes his way up to the attic, where he begins filling a metal tank with water… Henry Stuart arrives to inspect the Home. Admitted by Lou, he asks for Dearborn but is instead greeted by Dr Orloff, who explains that Dearborn has been called away and that he will give the tour. Lou, unseen, slips something into Stuart’s pocket… Stuart is impressed by the Home, and remarks that he wishes his daughter could see Dearborn’s work. When Orloff, startled, comments that he thought Stuart had no family, he explains that his daughter will shortly be returning from America. Orloff then leads Stuart to the clinic at the top of the house. There, Jake stalks towards him with a straitjacket in his hands…

Comments: Though it is hard to imagine given the substandard prints that for a long time were the only readily accessible way of viewing this film, when The Dark Eyes Of London was first released it was kind of a big deal—certainly in England, where in spite of his death some seven years earlier, the name “Edgar Wallace” still carried a real cachet. Released in 1924, Wallace’s novel of the same name had been a best-seller, and there were many people eagerly anticipating its transfer to the screen, particularly when word broke that the film was to star Bela Lugosi, who arrived in England in March of 1939 to great public interest—which is odd when you stop and think about it.

This wasn’t Bela’s first trip to England, but it was the more successful of the two. He had been there before in the early thirties, a trip that yielded only the mostly forgotten thriller, The Mystery Of The Marie Celeste aka Phantom Ship (which ought to be remembered, if for nothing else, for being made by Hammer Film Productions) and garnered him little attention despite his visit coinciding with the peak of the thirties horror boom.

However, this peak was also the beginning of the end. Although the British H-certificate, restricting audiences to sixteen years and upwards, had been introduced in 1932, largely as a result of Frankenstein, the increasing daring of the genre over the next few years finally produced a backlash that effectively killed the market for horror movies in England, particularly after the previously “advisory” H-rating became legally enforced—and which in turn saw the production of genre films dry up in Hollywood, as financially it was no longer worth it.

This had the unintended side-effect of opening up the field for British-produced horror – or at least “thrillers” – and as it turned out, The Dark Eyes Of London was the first British production to carry the enforced H-rating.

Of course, if there’s one thing we know about Homo sapiens, it’s that you only have to tell people they can’t have something to make them clamour for it. Bela Lugosi’s arrival in England in early 1939 just happened to coincide with the re-release of Dracula and Frankenstein, the double-bill doing smash business there as it had in America, in spite of the severe censoring of the two films. The name “Bela Lugosi” was news; and upon his arrival in the country the actor found himself the pleased beneficiary of a great deal of newspaper attention and even of a reception at the Waldorf.

(One of the guests at that reception was Hamilton Deane, who had originally adapted Dracula into a play, and who by that time had achieved his ambition of playing the lead role himself, in a series of revivals. But what was the culmination of a dream for Deane was years later an admission of defeat for Lugosi who, when his career nosedived, ended up re-donning the cape to support himself, including on the London stage. This third visit to England also produced Mother Riley Meets The Vampire, the less said about which, the better.)

(Which is my way of saying I’ll probably write a twenty-page review of it someday…)

The Dark Eyes Of London premiered in England in November of 1939 to generally very positive reviews. Curiously, given both the prevailing attitude to the horror genre and the film being released in the wake of, um, that other thing that happened in 1939, many of the reviews commented what a good thing it was that the film had been produced under H-certificate, as this had allowed the film-makers to “let rip” with the various horrors dreamed up by Edgar Wallace.

These days, however, we are likely to tag The Dark Eyes Of London as very marginal horror at worst. Oh, some horrifying things do happen in it, but “horror”, per se, is largely centred in the alarming figure of Jake, whose image dominates the advertising art for this film, even to the exclusion of Lugosi, and whose disfigurement is never explained. However, at the time the rising body-count and the emphasis on hands-on, cold-blooded murder would also have been shocking.

This is one of Edgar Wallace’s convoluted masquerade plots, with a supposedly respectable member of society eventually unmasked as the head of a criminal enterprise.

The film tips its hand about Orloff to the audience, at least up to a point, well before the good guys figure it out, which is all for the best because, let’s face it, with Lugosi you’re not fooling anyone. This film never goes to the extreme of “kindly Dr Carruthers”, but our very first glimpse of the equally kindly Dr Orloff makes it amusingly apparent who the villain of the piece is—even before Orloff goes into a rant about the fools in the medical profession who ruined his career.

The rest of the film plays out as a police procedural as much as anything else – the police were often the heroes of Wallace’s stories, as opposed to the amateur detectives admired by his contemporaries – and there is a pleasing emphasis on scientific methods in the investigation. There’s also a light love-plot, which is never allowed to get in the way of the story, and a certain amount of comic relief in the form of Lt Patrick O’Reilly of Chicago; although I’m relieved to be able to report that the film doesn’t carry its culture-clash material as far as it could have done, albeit quite far enough.

Meanwhile, though the low budget shows at pretty much every turn, leaving us with too many scenes of men in hats talking in bare rooms, overall there are enough creepy / odd / amusing moments to carry the production lightly through its brief running-time, as well as some nice shadowy compositions courtesy of director Walter Summers and his cinematographer, Bryan Langley.

The Dark Eyes Of London opens with what was by this time the obligatory close-up of Bela Lugosi’s eyes (later revealed as “blue” rather than “dark”, by the way) before showcasing the production’s two big names, Lugosi himself and Edgar Wallace. Everyone else connected with the film is effectively relegated to the status of “also with”, although Hugh Williams and Greta Gynt were both popular at the time and would certainly have helped to sell the film on its home soil.

The opening credits also carry the rather intriguing comment, The producers gratefully acknowledge the co-operation of the National Institute for the Blind, presumably with regard to such things as the use of the Stainsby machine, used for typing Braille; while the film itself emphasises the importance to the blind of supporting themselves through their own labour…although we do also have the tiny detail of a home for the blind being used as a front for a serial killer.

The Dark Eyes Of London then makes an early bid to be considered a horror movie proper, opening with a silent montage of dead bodies floating in the Thames. There have been five unexplained drowning deaths over the previous eight months, and the heat – somewhat tardily – is being turned on Scotland Yard. Although no individual death has raised suspicion, collectively they’re enough to provoke a protesting wail from the insurance underwriters compelled to fork out on them: each of the dead people being insured for a tidy sum.

The Police Commissioner is quite frank about the situation: “The Home Office is kicking, and I’m handing the kicks on to you,” he tells his hangdog subordinates.

Most of those kicks land on Detective Inspector Larry Holt, in charge of the sector in which three of the drowning victims have turned up. Holt is held back after his colleagues have been dismissed, and asked about the extradition of Fred Grogan, a forger, who Holt reports will be arriving from America in two days’ time.

The Commissioner, in turn, tells Holt that Grogan will be escorted by one Lt O’Reilly, who will be staying to observe “antiquated” British police methods. “I’ll attach him to you,” concludes the Commissioner. “Then he won’t learn anything.”

If we had any doubt about this being a British production in spirit as well as geography, we get it here, as after one hard breath and a, “Yes, sir,” uttered through clenched teeth, Holt makes his way to his own office, slams the door (which doesn’t catch, but hey, no time or money for re-takes here), and—orders a pot of tea.

At the Greenwich Insurance Company, Dr Feodor Orloff is writing out a cheque for a man called Henry Stuart, rather than the other way around. He gets Stuart to sign a note acknowledging the debt—in the process collecting a specimen of his signature.

Stuart is deeply grateful for the loan, which he promises to repay as soon as possible, and his gushing over Orloff’s kindness and generosity leads to a discussion of the latter’s charity work—which, we learn, is his way of helping mankind, now that his first-chosen path, the medical profession, has been effectively barred to him.

Ah, a Lugosi rant! – how I love a good Lugosi rant! If you see The Dark Eyes Of London for nothing else, folks, see it for this scene. It may not be about “a forsaken jungle hell”, but it ain’t bad, either:

Dr Orloff: “I wanted to devote my life to the healing of mankind. I wanted to be a doctor. But they got together, those narrow-minded, prejudiced medical men, to see how they could ruin me! [*chuckles*] ‘Brilliant but unbalanced’ – that was the verdict. And so—I serve the blind…”

So, his medical career thwarted, Orloff decided to revenge himself upon mankind by becoming—an insurance broker?

Makes sense.

Here we learn about Dearborn’s Home for the Destitute Blind, with Orloff suggesting – very strongly – that Stuart visit there the following evening. This is oddly executed: we certainly assume that Stuart is having the standard Lugosi-whammy put on him here, but he replies to Orloff quite normally, with no hesitation or slow speech or blank eyes to suggest that he has been influenced, which rather begs the question of why he doesn’t seem to notice anything odd about Orloff’s manner. But maybe he’s just being very British.

And maybe Orloff just thinks he has mind-control powers.

Orloff’s secretary, played by an unspeaking Julie Suedo, enters here; and again, oddness prevails. Orloff certainly puts the whammy on her at one point, and there are times when she appears to be “under the influence”, as it were; but there are other times when she appears to be acting entirely of her own volition—and it doesn’t really seem determined by the immediate nefariousness of Orloff’s actions.

Perhaps – to make an ironic comparison – this is something like how Lugosi himself was handled in Frankenstein Meets The Wolf Man, that is, they changed their mind about the character on the fly but didn’t re-shoot. However, I prefer to stick with the “Orloff is delusional” reading, and imagine that this poor woman is playing along with him simply in order to keep her job.

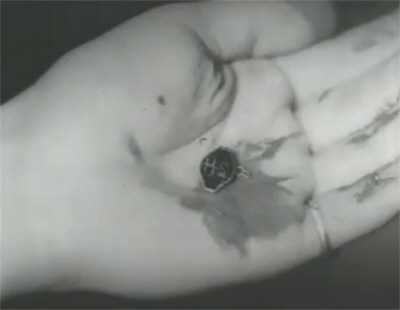

The Stainsby machine makes its first appearance here, as we watch Orloff (or his hand-double) type out a message in Braille. All through this sequence there has been violin music in the background, belatedly explained when the departing Stuart drops a coin into the collection tin of the musician, declared by a sign around his neck to be both dumb and blind.

Now, Orloff takes the strip of paper with the Braille message, wraps it around a coin, and tosses it out the window—which doesn’t seem like the most efficient means of communication, particularly when the small package lands in a puddle. Be that as it may, the violinist, Lou by name, gropes around until he finds it, tucks it into a pocket, and immediately taps his way off down the street.

Inspector Holt then pays a call upon Dr Orloff, and with only a very general explanation asks to see his books. Orloff hesitates but, clearly unable to think of a good excuse, has to hand them over. Holt asks about two people in particular, a man call Ingalls and a woman called Sable, both of whom drowned, and both of whom, according to Orloff’s vague recollection, had beneficiaries who have since left the country. Fancy.

It is evening before poor Lou reaches the Dearborn Home and rings the doorbell. Here we get our first look at Mr Dearborn himself, with his white hair and moustache and dark glasses. Hearing the bell he says gently, “Answer it, Jake”, and – in what I imagine was another jolt for audiences in 1939 – we also get our first look at Jake…

At the front door, Jake greets Lou, who slips him the strip of Braille. He reads it and seems distressed, but does not speak. Instead, with a gentleness belied by his appearance, Jake helps Lou into the dining-room, where the other residents of the Dearborn Home are gathered about the table, while Dearborn himself reads from a Braille bible, his gentle tones soothing the spirits of his little flock. (Although I do hope he doesn’t make them listen to the one about the blind seeing every night.) Meanwhile, Jake slips upstairs, and is briefly glimpsed pumping water….

Henry Stuart arrives at the Dearborn Home – as ordered? – and again we can tell this is a British film, as he stops to select the correct taxi-fare from a handful of coins, rather than shoving the first money that comes to hand at the driver and walking away. Stuart is admitted by Lou, who is agitated by his presence and tries to slip him a strip of Braille. He is interrupted by the arrival, not of Dearborn, but of Orloff, who explains that Dearborn has been called away, and that he will therefore have the pleasure of showing Stuart around. As the two turn away, Lou slips the Braille massage into Stuart’s pocket.

Stuart is first shown the dining-area, and then the open room in which the home’s residents weave baskets, which are sold to provide them with an income. Impressed, he comments that he wishes his daughter could see it. This leads to one of the film’s funnier moments, with Orloff jerking around and exclaiming indignantly, “Daughter!? What daughter? I thought you had no relatives!”

Stuart – un-whammied, yet again apparently not bothered by either Orloff’s peculiar manner or his rude questions – explains placidly that his daughter has been in America, but is presently on her way home. This has the effect of, shall we say, speeding up a certain process. Orloff invites Stuart upstairs to see the clinic he has created for the home, where he provides medical care for the residents.

Among other things.

The first thing Stuart sees inside the clinic is Jake, alarming enough even without the straitjacket in his hands. After a frozen moment Stuart bolts for the door, but Orloff is behind him and swings it shut…

The next day, Holt is at Victoria Station for the arrival of the boat train carrying the forger, Fred Grogan, and his minder, the American detective, O’Reilly. An extremely weak cute-meet follows, as in his eagerness to reclaim Fred Grogan, Holt barges forward into a young woman passing through the barriers ahead of the forger, steps on her foot, and is immediately smitten by her.

More British-ism follows: Grogan is unrestrained, and just stands there smiling indulgently as Holt and O’Reilly shake hands, and as Holt excuses himself to go after the girl; and even after Holt and O’Reilly manage to handcuff themselves together (don’t ask), Grogan obligingly wanders over to the waiting paddy-wagon and climbs in unasked—checking his watch in disgust as the two police officers discover that O’Reilly doesn’t have the key…

Much funnier is the reception of this less than glorious interlude by Holt’s boss, who again proves himself the master of a wounding word by informing his subordinate that he has managed to, “Keep your Lower Fourth antics out of the papers”, and O’Reilly that, “The Yard is a dour, soulless place of business, where hi-jinks, jitterbugs and horseplay of the more imaginative kind are severely discouraged.”

(I would have called the bit with the handcuffs highly unimaginative, but moving on…)

A phone-call proves a welcome interruption, at least until it turns out to be about the discovery of another drowning victim. This time, Holt orders everything left untouched, and heads out to the scene with O’Reilly in tow.

The body cast up upon the stone steps at the edge of the Thames is bearing identification. Holt also finds on the body one-half of a broken cufflink bearing the initials ‘H. S.’, which he carefully preserves.

While looking on, O’Reilly manages to drop his cigar-case, thus establishing the Thames mud as quicksand-like in consistency and action.

Mwoo-ha-ha…

At the morgue, the death of Henry Stuart is confirmed as a drowning which occurred about three hours before his body was found. Holt asks that the water in the stomach be analysed. A message then comes that the next-of-kin has arrived to identify the body—and a dismayed Holt finds himself face-to-face with the girl from the station, Diana Stuart. She makes the formal identification bravely, but is unable to face immediate questioning. Holt has her taken to a room where she can – what else? – bolster her nerves with a cup of tea.

In the wake of her exit, Holt learns that a soggy strip of Braille has been found in the dead man’s pocket.

In the police cells, Fred Grogan’s general state of indignation reaches new heights with the intrusion into his cell of a drunk: the loud, happy, laughing, singing kind. The only amelioration is that this new cell-mate has a newspaper in his pocket, which Grogan appropriates at the first opportunity, seeking out a small, coded message in the personals.

Meanwhile, Diana Stuart is sipping her tea under the kindly eye of Police Constable Griggs – a policewoman – thus kicking off a running joke that is rather hard to interpret. It can’t be PC Griggs’ mere existence that startles O’Reilly so much, as there had been policewomen in America for nearly three decades at this point; but perhaps it’s her presence at Scotland Yard, American policewomen being debarred from “serious” police work via the simple expedient of forbidding them the beat experience necessary for promotion.

So maybe it’s Griggs’ uniform, certainly a remarkable piece of sartorial eloquence. Or maybe it’s the just the revelation of her assignment – “the promotion of public morality”.

When Holt does begin questioning her, Diana is adamant that her father did not commit suicide: that he had no enemies, and no serious worries; while Holt reveals his own belief that it wasn’t an accident, either. He asks her not to communicate with any stranger without letting him know first.

We then get the revelation that the “drunk” was no drunk at all, but a plant to make sure Grogan got a look at the newspaper. Our no longer laughing and singing friend reports Grogan’s interest in a particular personal ad, which Holt sends off to be decoded. He then orders Grogan brought up for questioning, upon which O’Reilly begins literally rubbing his hands together in glee at the prospect of “making him sing”.

“There’s no third degree in this country,” replies Holt placidly, waving away O’Reilly’s piece of rubber hose. “Here we catch our crooks by kindness.”

As a demonstration, Holt tells Grogan that he won’t be opposing his bail—although he can’t get Grogan to reciprocate by telling him who’s posting it. As O’Reilly looks on in disgust, much mutual jocularity follows (including the alarming threat of Holt having a little Grogan named after him), before the forger is led back to his cell.

As he goes out, the decoder of the ad comes in, reporting that it’s simple enough: the first letters mean “Grogan”, the rest, “Orloff”. Holt orders a tail put on Grogan from the moment he leaves the courthouse.

The following sequence is presumably intended to demonstrate that British methods aren’t so antiquated after all; O’Reilly is suitably impressed. First it’s off to the lab – whee! – where Holt views pictures of the body, checks on the high- and low-tide times, and learns that the water in Stuart’s stomach was clear, when it ought to have been cloudy—that it was tap-water, in fact. The unravelling of the Braille is not so entirely satisfactory, but still suggestive: although most of the message is too damaged to be deciphered, the first three letters are M – U – R –

The next morning finds a post-bail Grogan adding what we take to be Henry Stuart’s signature to an insurance policy—but under protest, having heard enough while in custody to know that he’s now an accessory to murder. Unwisely, he tries to use this knowledge as leverage to free himself from Orloff, who doesn’t take too kindly to the prospect. Grogan retreats, but too late:

Grogan: “Don’t you worry, I won’t squeal: I’m not that kind.”

Orloff: “No. You – won’t – squeal.”

Orloff then sends another message via the Lou-Express, before hearing footsteps on the stairs. Orloff and Grogan rush to tidy up, and have barely done so before Holt and O’Reilly wander in. Awkward.

Holt is pleased if anything to see Grogan there, and again allows him to scuttle off, while Orloff airily explains away his presence as the result of his own activities as “Vice-President of the Prisoners’ Relief Association”, adding that Grogan was asking his help in mounting his defence.

What follows is the film’s single most exquisite touch:

O’Reilly: “The nerve of that guy, asking you to put up the jack for his mouthpiece!”

Orloff [smiling at Holt]: “Your colleague is a foreigner?”

Knowing the way that Bela’s career ended up going, there was always something sweetly poignant about those moments in his films where you could see him enjoying himself…and honestly, I’m not sure there was ever a moment he enjoyed quite as much as that one. Overall, too, his evident relish of Orloff’s dastardly proceedings helps to make the film seem better than it objectively is.

Orloff admits that, yes, he knew Stuart, and that, yes, he had a policy; but that he was also in a financial mess, and that he, Orloff, had lent him the money to pay his last premiums…which is why he is the beneficiary of that policy…

(There’s an odd moment here when Orloff whammies his secretary before having her take away the lock-box in which has various incriminating documents hidden, which hardly seems necessary.)

A highly sceptical Holt sits down to copy out the details of Henry Stuart’s policy, but must ask for more ink, at which Orloff hurriedly intervenes. We assume that the first ink-pot was the one with which “Stuart” signed his policy. When the detectives have gone, Orloff orders his secretary to claim on Stuart’s policy at once, and then to get him Diana’s phone-number…

Meanwhile, the Lou-Express has reached its destination, and Jake pays Grogan a little visit. Unfortunately for the latter, he just happens to be taking a bath…

Hmm. I wonder what the odds were of Jake showing up just at that juncture? – Grogan not striking us as the cleanliness / godliness type. I also wonder what happened to that tail that was supposed to be on Grogan?

(I also also wonder who’s been looking after Grogan’s pot-plant while he was in America…?)

Holt, O’Reilly and a plainclothes subordinate show up in the immediate wake of Jake’s departure, and after a moment’s silent wincing the detectives leave their luckless colleague to a futile attempt at resuscitation.

“Don’t they ever shoot anyone in this country?” O’Reilly demands plaintively, while Holt phones in Grogan’s death and learns that, as per his instructions, Diana has reported being contacted by a stranger, Orloff—but has accepted an invitation to his house anyway.

There, Diana rather unwisely announces her determination to hunt down her father’s killer. Orloff tells her that she shouldn’t dwell on the past, but look to the future. He offers to arrange for her a position as Dearborn’s secretary, explaining about his blindness and his need for a sighted assistant. She gratefully accepts.

Leaving Orloff’s, Diana climbs into a taxi and gives her address, but becomes alarmed when it takes another way. Not to worry: it’s Holt behind the wheel. He tells her of Grogan’s death and warns her sternly of her own danger; but she responds that far from posing a threat, Orloff has been kind enough to find her a job. Hearing that it’s at the Home, Holt takes the plunge and recruits her, telling her to keep her eyes open, and in touch with him.

At the Home, Dearborn shows Diana around downstairs and introduces her to the residents, before taking her up to the clinic where Lou is writhing on a bed with Jake in attendance. As everyone does the first time, Diana stops dead in her tracks and gawps at Jake who, in his distress over the obviously seriously unwell Lou, doesn’t seem to notice.

Back in the office, Dearborn and Diana find Holt and O’Reilly waiting for them, everyone playing dumb behind Dearborn’s back (so to speak). Holt asks Dearborn to try and read the message that was found in Stuart’s pocket, but he insists that he can only decipher the first letter, ‘M’. Hearing where the message was found, Dearborn becomes distressed. The detectives then withdraw—O’Reilly having an unwise nudge-nudge word with Diana on the way out.

Before departing himself, Dearborn gives Diana her instructions, including, should Orloff come, to send him up to Lou right away.

Unluckily for Lou, Orloff does show up—and he’s not happy. Getting rid of Jake by sending him to find Dearborn, Orloff prepares for an “experiment”. He plugs what look like ear-phones into a generator, straps Lou’s arms down to restrict his movements—and then has a word with him about how, exactly, that Braille strip got into Henry Stuart’s pocket…

“The police have been here. They might come back and ask you questions,” comments Orloff. “You’re blind…and you can’t speak…but you can hear…and that will never do…”

And then Orloff comes at Lou with the ear-phones…

And now we reach the point of the film where everyone starts acting stupidly: a shame, but at least the stupidity is fairly evenly distributed. First of all, in the course of her duties, Diana finds Henry Stuart’s cheque for fifty pounds, a donation to the Dearborn Home, along with a note declaring his intention of visiting the home on the evening of his death. Because if you had just lured a man to his death, you would of course leave the evidence of it lying around where his daughter can find it.

Orloff walks in on Diana while she is staring at the documents in dawning horror, and she reacts by hardly responding to his greeting while she shoves all the papers she’s working on into a lock-box, placing the lock-box in a drawer, locking the drawer, depositing the key in another drawer, and hurrying out of the room…upon which Orloff retrieves the key, unlocks the drawer, opens the lock-box, and possesses himself of the documents.

Since Orloff has no business amongst the Home’s papers, and since she’s hurrying off to Holt to tell him all about it, we may well ask why she didn’t just take the letter with her. Sadly, this will only be the second dumbest thing Diana does. Or possibly the third.

At any rate, Diana doesn’t go to Scotland Yard, but to her apartment, and phones Holt from there; so she’s at home when Jake comes calling. Her first intimation of something wrong is when her lights go out…

Meanwhile, Holt receives confirmation of the claim on Stuart’s policy, which for him is the last piece of the puzzle. We also hear in passing of the “megalomaniacal streak” that got Orloff kicked out of the medical profession, but alas, without elaboration. Diana’s call then comes through—and her hysterical screaming down the line sends the detectives bolting for a car.

In the land of the blind, as they say, the one-eyed man is king: Jake can see, just, but bright lights hurt his eyes. Discovering this, Diana realises it gives her a way of fighting back. She first dodges about the room as Jake gropes for her in the dark, then makes a break for the bedroom, where she locks the door. (So she has a key-lock on her bedroom, but doesn’t bother to lock her front door? Interesting…) Jake soon forces his way in, but his first action is not to grab Diana but, once again, to turn out the lights. Diana, in turn, bolts to her bedside table and switches on the lamp, which she shoves into Jake’s face. It slows him down, but only a little. He crushes the bulb in his hand, roaring angrily, before seizing his prey—

—at which moment, Holt and O’Reilly arrive…and ring the doorbell…

Not surprisingly, no-one answers. So they knock. And when even that fails to attract the attention of the snarling homicidal maniac and his terrified victim, they finally get around to bursting the door open.

(Which, the way, implies that Jake stopped and locked it before attacking Diana, which he did not…)

Hearing them, Jake exits via the fire-escape. O’Reilly fires at him as he flees, but misses. (Feh! – some Chicago cop.) Diana identifies her attacker, and declares wildly that she can’t go back to the Home.

However, in an unusual bit of tough-mindedness, Holt insists that she must; that they don’t yet have enough proof against Orloff. With a squad for back-up, and O’Reilly all excited now that the time for action has arrived, they raid the Greenwich Insurance Company, where our heroes must once again force open a door.

In fact, I’m pretty sure that the last section of this film features the highest door-bursting-per-minute ratio of any ever made…

However, Orloff is nowhere to be found. Holt initiates an official hue and cry, but Orloff seems to have vanished, in spite of all the superimposed newspapers.

(And unless my eyes deceive me, one of them has a photo of a much-younger “Orloff” wearing a cape….)

Dearborn is naturally very interested in the case, and one of Diana’s duties becomes reading the press coverage to him. The detectives show up, but to their disgust Dearborn only wants to talk about how kind and generous Orloff always was. Holt demands to see the clinic, and Dearborn leads him up to it. The men find Jake (Holt’s ace up his sleeve) at the bedside of poor Lou, who does not respond when spoken to. Looking around, Holt asks what the iron tank is for, but Dearborn replies apologetically that only Dr Orloff could tell him that.

When they have gone, a worried Jake speaks to Lou, but he can’t get a response from him either. Realising that Lou wasn’t just foxing to avoid police questioning, Jake grows increasingly agitated.

Insisting that Lou must still be capable of answering in writing, Holt gives Dearborn a list of questions to be transcribed into Braille. When the detectives have gone, Dearborn asks Diana to get one of the blind men to help her type out the questions. She is obediently fetching a Stainsby machine from the indicated cupboard when she happens to notice lying beside it half of a broken cufflink.

Because if you had just lured a man to his death, you would of course not only leave the evidence of it lying around where his daughter can find it, but point her in its direction. (For that matter, why keep it in the first place??)

And Diana— Does she call Holt? Does she take the cufflink to him? She does not. Instead, she snatches it up and storms out – passing a table where, knowingly or unknowingly, the blind men are turning large piles of money into numerous tidy packages – running up the stairs and into the clinic, where she confronts Dearborn with the object.

“I can’t recall ever having seen it before,” he replies.

Whoopsie.

But, as it turns out, the fact that he can see is only one of Dearborn’s little secrets…

Wonderfully, this piece of camouflage seems to have taken a great many people by surprise at the time of the film’s release – and who knows? – perhaps even later. There is some clever misdirection about the supposed locations of the “two” men, with Orloff sending for Dearborn and so on, but in the end it’s the voice that does it: those gentle, inimitably British accents (supplied by O. B. Clarence) in place of the unique Lugosi patois. And in retrospect, the fact that this terribly English voice is supposed to be issuing from Bela Lugosi is nothing short of hilarious.

But anyway, Diana isn’t finding it so funny. So shocked is she by this revelation that she barely struggles while Orloff puts the straitjacket on her (or at least, that’s her story). We notice here that Orloff doesn’t seem to understand how a straitjacket actually works as, having used the arms simply as ties, he follows up by further binding Diana with rope, and tying her to the bedstead.

And with Diana incapacitated, Orloff stops to take care of the oblivious Lou, dumping him unceremoniously into the tank.

Having done so, however, Orloff then obligingly stops to explain to Diana how the building used to be a warehouse, and how it overhangs the river—throwing open two large wooden doors as he speaks. He further explains that in her father’s case, because of uncooperative tides, Jake had to carry the body to the river; thus accounting for a discrepancy in timing noticed by Holt.

And with all that out of the way, Orloff tosses what’s left of Lou out the doors and down onto the mudflats below, chortling merrily as he does so.

Then curiously, after revealing his plans for escaping on his yacht after disposing of the last (yuck, yuck) eye-witness, Orloff calls for Jake. What, suddenly squeamish?

Back at Scotland Yard, Holt gets a call from the river police about a boat near Dearborn’s, which once more sends him and O’Reilly to the scene.

Leaving Jake to do his dirty work, Orloff departs to oversee the last of the money-bundling. Jake undoes the rope and lifts Diana over his shoulder, carrying her effortlessly towards the tank in spite of her desperate pleas for mercy. She manages to delay her fate by getting the balls of her feet wedged against the edge of the tank, and then utters the words that will save her life:

“Jake, where’s Lou?”

Sure enough, Jake puts Diana down (rather than, say, dropping her into the tank) while he investigates this pressing question; and his howls of, “Lou, Lou!” are heard all over the house, bringing Orloff back up to see what the matter is.

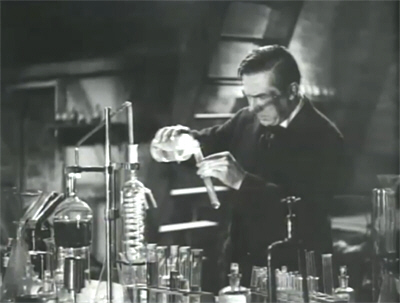

Jake, meanwhile, is on a rampage; and having wrecked the bed that undoubtedly no longer contains Lou, he turns his attention to a collection of test tubes, retorts, and flasks filled with Mysterious Coloured Fluids, which Orloff has because—-

Okay, you’ll have to get back to me on that one. Aw, heck: does he really need a reason?

As Orloff enters, very cross that Diana isn’t dead yet, Jake stalks towards him grunting, “You killed Lou!”, and is promptly shot in the gut. Orloff then comments disgustedly that he will have to take care of Diana himself.

Downstairs, the cavalry finally arrives, and this time the situation is so desperate, O’Reilly gets to shoot the locked front door open instead of using his poor bruised shoulder on it.

At the sound of the shots, Orloff pushes Diana away and makes for his other supply of test tubes, retorts and flasks filled with Mysterious Coloured Fluids. He prepares and carefully seals a smoking concoction, then picks up two more sealed test tubes and binds them all together.

SCIENCE!!!!

As the police pour in (rather slowly), Orloff stops on the stairs and hurls his test tubes, which turn out to comprise nothing more dangerous than a smoke-bomb. He then starts shooting. O’Reilly returns fire and wings him (which is either very good shooting or very bad shooting for a Chicago cop, depending on how you look at it). Orloff is forced to retreat up the stairs, and locks himself into the clinic, meaning to make a run for it via the roof—only Jake isn’t quite as dead as he supposed…

As Jake staggers across the room and throws open the doors, Orloff rushes up and tries to push him out. Jake manages to regain his balance and then gets a death-grip on his former master, dragging him across the room and tossing him through the doors.

Orloff plunges into the mud, which engulfs him almost up to his chin—and screams in terror as it drags him inexorably down…

And where are Holt and O’Reilly all this time? Where else? – trying the burst the clinic door open. They finally manage it, just in time to see Jake collapse and die.

So to summarise—

The serial killer terrorising London is stopped by a straitjacketed girl and a dying homicidal maniac, rather than by the combined efforts of the police forces of two countries.

Good show!

Want a second opinion of The Dark Eyes Of London (aka The Human Monster?) Visit 1000 Misspent Hours – And Counting.

♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦

This review is part of the B-Masters’ tribute to Edgar Wallace (also Bryan). Click here for more!

They killed Pa Ingalls? The brutes!

LikeLike

AND enjoyed it!

LikeLike

I have a trapdoor over the Thames. But I shall not simply knock my victims unconscious and drop them into the river to drown; instead I shall drown them here, then pitch them out. Yes, that makes sense.

My word, that kerning in “INSUR [great big gap] ANCE MONITOR”…

LikeLike

😀

Ah, but this way there are no signs of violence on the body; and given that it’s the 6th murder before anyone thinks to question the circumstances, I’m not sure you can argue with the reasoning! It’s only when Diana’s return rushes the Stuart timeline that things go wrong.

LikeLike

I remember seeing a movie some time ago with a similar plot (of course, it could have been this one, the details are fuzzy). But what I remember best is all the blind inhabitants realizing that they’ve been made fools of, and take revenge in their own hands. Did that happen in this one?

BTW, I don’t click on the ‘Notify me of new comments’ box, but I seem to be getting the emails anyways. Has anyone else noticed this?

LikeLike

Happened to me, too.

LikeLike

It was also filmed as Dead Eyes Of London in the 60s, one of the German krimis that were so obsessed with Wallace. Possibly that was the ending of the book? (I haven’t read it, though I think I have a copy around somewhere.) It may have been out of step with the “co-operation of the National Institute for the Blind” thing here, or maybe just a bridge too far with the censors. As it is, it isn’t clear if the blind guys realise how they’ve been used, and they’re just kind of there when the gas-bombs and bullets start flying.

If you want the emails to stop, I can poke around and see if there’s an admin box I can unclick?

LikeLike

I just send it to Spam, along with all the other unnecessary emails. For some reason, someone out there in the ethernet thinks I’m interested in exotic/ethnic/Russian/Ukrainian women, have prostrate problems, and need info on how to get ‘hard’. No to all three.

Maybe they have the wrong gender? Would have thought ‘Dawn’ was obviously female, but maybe not.

LikeLike

Unwanted emails here too – I already get the comments via RSS.

(Been away for a few days.)

LikeLike

good news, I did NOT get an email notifying me of your latest comment. I had to come and look myself.

Which I’m always happy to do.

LikeLike

Heck, put my reply in the wrong spot. I’ll repost here.

dawn, this sounds like “Blind Alley,” an EC Comics tale adapted in the early seventies portmanteau film, “Tales from the Crypt.” At the end of the story, the abusive manager of the facility is forced to walk an improvised maze, the walls of which are studded with razor blades. Then the residents turn off the lights.

LikeLike

I did see that story. There are actually 2 versions of that, one where the manager is a military man, and the other where he’s the son of the woman who founded the facility, and always resented her use of the money.

Not only the razor blades, but also 2 very large dogs that are turned loose on the manager.

The movie I remember was in black and white. I may just be remembering what I wanted to happen. It’s always satisfying when the victims are able to take revenge.

LikeLike

BOWERY AT MIDNIGHT (1942) has a slim similar plot with Bela playing a double life, one kind and helpful to the poor people, and another as a sleazy criminal who turns those poor people into zombies. At the end they turn on him violently. Not a classic, but a fun film with a crazy ending: the heroe, who was converted into a zombie, lives happily ever after with his girl! (Apparently he was cured, but…)

LikeLike

I’ve seen that, a very early WTF-film that I need to take another look at sometime. 🙂

LikeLike

Another great review, as always.

Check out the latest issue of “Little Shoppe of Horrors” for an interview with Greta Gynt.

LikeLike

Thanks! 🙂

LikeLike

I was watching the Doctor Who story Vengeance on Varos today, and was delighted to hear the good Doc yell at a man dressed in a Phantom of the Opera mask and leather jumpsuit…”And you call yourself a research scientist!”

LikeLike

😀

LikeLike

dawn, this sounds like “Blind Alley,” an EC Comics tale adapted in the early seventies portmanteau film, “Tales from the Crypt.” At the end of the story, the abusive manager of the facility is forced to walk an improvised maze, the walls of which are studded with razor blades. Then the residents turn off the lights.

LikeLike