“You don’t mean to say you really like these beasts!?”

“I love them. Their honesty, their simplicity; their primitive emotions. They love, they hate – they kill…”

Director: A. Edward Sutherland

Starring: Lionel Atwill, Randolph Scott, Charles Ruggles, Gail Patrick, Kathleen Burke, Harry Beresford, John Lodge

Screenplay: Philip Wylie, Seton I. Miller and Milton Herbert Gropper (uncredited)

Synopsis: In the jungle of French Indochina, millionaire sportsman and animal collector Eric Gorman (Lionel Atwill) disposes of the man he believes to be his wife’s lover by binding him hand and foot and leaving him to the animals. Later, a native brings to Gorman’s camp a piece of bloody clothing, speaking ominously of tigers… On the long shipboard journey home to America, Evelyn Gorman (Kathleen Burke) and a man called Roger Hewitt (John Lodge) meet and begin to fall in love; but Evelyn, who has put her own construction on the events in the jungle and is terrified of what her husband might do, warns Hewitt away. Meanwhile, the Municipal Zoo that is the intended destination for Gorman’s captured animals is struggling financially, having had its budget cut for the fourth time. Zoo curator Professor Evans (Harry Beresford) hires press agent Peter Yates (Charles Ruggles) to drum up publicity and, hopefully, donations. Yates is a recovering alcoholic, but swears that he is on the wagon. Evans introduces Yates to Dr Jack Woodford (Randolph Scott), a biochemist and toxicologist developing new antitoxins for snakebite, and to his daughter, Jerry (Gail Patrick), who works as Woodford’s assistant. Yates’ first assignment is to arrange for reporters and photographers to gather at the dock to record Gorman’s return. Yates goes to the Gormans’ suite on the boat and greets a man he assumes is Gorman, but who an embarrassed Evelyn introduces as a Mr Hewitt. She then sends Yates to the hold, where Gorman is checking on the welfare of his animals; in the course of their conversation, Yates mentions the presence of another man in Evelyn’s rooms. At the zoo, while the animals are being settled in, Evans tells Gorman of the zoo’s financial troubles. Yates suggests a fund-raising dinner, held at the zoo and amongst the caged animals. To Evans’ surprise, Gorman jumps at the idea, even offering to arrange the dinner himself. Gorman then greets Woodford, to whom he has brought a rare and valuable specimen for his research: a green mamba. Gorman warns Woodford that the animal’s venom is the swiftest acting of any species of snake. At Roger Hewitt’s apartment, he and Evelyn make plans for her to leave her husband. Hewitt insists that she leave for Paris, and that he will join her as soon as her divorce becomes final. To their horror, the two are interrupted by Gorman himself. Evelyn hides in the next room, from where she hears her strangely genial husband invite Hewitt to the zoo’s fund-raiser. At the dinner, which is held in the Carnivore House, Hewitt finds himself seated next to Evelyn – but opposite Gorman. Yates primes the photographers he has invited, then begins to make a speech, welcoming the guests and thanking Gorman. He is startlingly interrupted, however, when Hewitt suddenly lurches to his feet, crying out in agony. He then collapses. Hewitt is carried into the next room, where Woodford examines him, finding evidence of snakebite. He sends Jerry to inspect their snakes. She returns with the grim news that the green mamba has escaped…

Comments: Although it was introduced in 1930, the Motion Picture Production Code remained essentially a paper tiger until 1934, when an amendment requiring all films to receive an official “Seal Of Approval” before they could be released to cinemas was adopted. Prior to 1st July, 1934, however, when that amendment was enforced, many film-makers chose to ignore the Code, serving up sex, violence, criminality and general disrespect for authority of all kinds in whatever sized doses they pleased. It is small wonder that the American horror movie not only germinated, but flourished, during this time; with the freedom to take risks, the studios began venturing into some surprising territory in their effort to feed the public’s appetite for these dark delights. Sometimes, it was considered, they went too far, and attacks from reviewers, church and civic leaders, and other concerned parties would result. In return, sometimes the studios would listen and respond; and sometimes they would thumb their noses and carry on.

Of the nose-thumbers, the two main guilty parties were Warner Bros. and Paramount. Unalike in almost every other way, these two studios, with their social commentaries and crime films on the one hand, and their sophisticated sex comedies on the other, displayed an equal and comprehensive disregard for the tenets of the Code; indeed, their combined output at this time almost exactly defines what would end up outlawed once the Code was actually enforced.

Curiously, it was also these two studios that gave a new twist to the increasing social debate over the latest “threat to decent society” to emanate from Hollywood, the horror movie. On the whole, horror movies tended to be more acceptable to their detractors if they were set either in the past, or in what could be considered a fantasy world; the expression “fantasy” encompassing everything from the “Mittel Europe” of the Universal horrors to the Haiti of White Zombie, which was judged far enough out of the normal experience of movie-going America to be considered mythical.

Horror movies set in a recognisable reality were, however, another matter. It was Warner Bros., predictably, that dragged the horror movie away from its gothic roots and planted it in modern America with their one-two punch of Doctor X and Mystery Of The Wax Museum, upsetting the critics with their insistence that behind the bustling façade of your average city, madness and murder were lurking. And while Paramount’s first two horror productions, Dr Jekyll And Mr Hyde and Island Of Lost Souls, met the fantasy requirement by being set in the past and on a fictional island, respectively, their third horror production was not only absolutely contemporary, but opened with a scene so bluntly confrontational, it remains jolting to this very day.

I will return to that opening scene presently. Murders In The Zoo is shocking in some other ways, too, which may well prove distressing to modern viewers. This is only a very short film, just over an hour long, yet still has various sequences of padding in the form of footage of the animals supposedly in the titular zoo. This is not actually stock footage in the usual sense of that expression; the visual similarity of these scenes to the rest of the film indicates that they were shot specifically for this film. This was an era in zoo-history when thick metal bars, concrete pits and a bit of scattered straw were the norm; and while this is not, of course, in any way this movie’s fault, these scenes are depressing just the same.

Even more so are those involving Eric Gorman’s captured animals, which for much of the time occupy bare, restricted boxes in which they hardly have room to move; a disturbing touch that certainly was the production’s choice. (On the other hand, there’s the fact that the big cats are in unguarded cages with the bars so far apart, they can get their paws through the gap.) At the film’s climax, in order to create a diversion, Gorman opens the main cat cages and lets loose the various felines, which dart about in alarm, fear and anger in their confined space before, inevitably, attacking one another. A smallish jaguar, in particular, takes a terrible beating from a large lion.

This kind of thing was, unhappily, an extremely common feature in film-making of this era, particularly the serials. The Clyde Beatty serials, for example, feature numerous sequences of animals being mishandled – sorry, tamed – supposedly as a demonstrations of their captor’s courage; while Universal’s Call Of The Savage returns again and again to a certain grassy “arena”, where disparate animals are thrown together and provoked into fighting for the supposed edification of the audience.

Eric Gorman’s release of his captive cats follows from an earlier, unsuccessful attempt to make a murder look like an accidental death, a plan that entails leaving a dead snake by the victim. In pursuit of this, Gorman releases the film’s mamba from its cage, and beats it to death as it moves across the floor. The beating happens off-camera, granted, but that snake is horribly limp when Gorman picks it up again; and try as I might, I haven’t been able to convince myself the killing wasn’t real. If it was, it was also in all respects unconscionable: Gorman / Atwill’s body-movements could have conveyed to us what he was doing; there was no need to show a motionless snake.

So parts of Murders In The Zoo are pretty tough going. The film is tough going in another way, too; a far more, shall we say, traditional way. I remember once describing Murders In The Zoo to someone as, “Half of an excellent horror movie.” If the treatment of its animals is one serious problem working against the success of this film, another is the horribly unfunny contribution of Charlie Ruggles as the rambling, repetitious, jittery, cowardly, ex-alcoholic, animal-hating press agent, Peter Yates. Yes, my friends: Yates is indeed our Odious Comic Relief, and every moment that he is on screen is sheer torment.

In context, though, you can make some excuse for the film here, inasmuch as Yates is “comic relief” by the literal definition of that expression; he is there to provide the audience with intermittent reprieves from what is otherwise one of the most grim and twisted horror films of its era. It can well be imagined, at a time when movie viewers were screaming and fainting at Lugosi’s Dracula, that such relief might have been very welcome indeed.

Which thankfully brings us to the other half of this film, the excellent half, and in particular to that notorious opening scene. In fact, Murders In The Zoo opens with a marvellous bait-and-switch. Its opening credits play over shots of the zoo, accompanied by jolly calliope music, and pre-empting The Women’s famous opening by six years have each cast member represented by a particular animal; suggesting, all in all, that this film will be a fairly light-hearted affair.

From there we cut in medias res to French Indochina, where two natives hold down a struggling man while a fourth party does something to him that we can’t quite see…although he appears to be sewing… “You’ll never lie to a friend again,” comments the man who we will soon know as Eric Gorman. “You’ll never kiss another man’s wife.” With that, Gorman and the natives ride away, leaving the struggling man behind on the ground. He staggers to his feet and through the jungle, his hands still bound behind his back and uttering only strange, incoherent grunting noises, until he swings around to face the camera, and shows us his mouth – the lips sown bloodily shut…

You might think that nothing could top an opening like that, but you’d be wrong. The icing on the cake comes when Eric Gorman returns to his jungle camp. Evelyn Gorman, noticing that the man, Taylor, is missing, asks after him. Gorman explains that he went on to another village, making reference to “what happened” and Taylor’s probable embarrassment. That isn’t good enough for the worried Evelyn.

“But what did he say?” she presses her husband.

“He didn’t say anything,” replies Gorman.

It is, truly, moments like that that can make someone a film fan, and the fan of a particular actor, for life. Lionel Atwill may never quite have made the upper echelon of horror movie icons, but there were few of his films in which he was not one of the best things about them. It was not only his way with a line of dialogue that made Atwill such a valuable property; once the Production Code was enforced and horror movies became perforce altogether more discreet, his ability to convey all manner of unspeakable things purely through the glint in his eyes became a priceless asset.

(Bizarrely, in Murders In The Zoo, Lionel Atwill actually suffered the humiliation of being billed below Charlie Ruggles! In his book, Classics Of The Horror Film, William K. Everson suggests that this was because Ruggles was on contract to Paramount, and Atwill only a visitor.)

We next see the Gormans on their way home to America. Although we parted from them in French Indochina, which at the time comprised Vietnam, Laos, and part of what is now Thailand, the Gormans’ boat has sailed from India, indicating that quite some time has passed; long enough, indeed, for Evelyn Gorman to have met and fallen in love with another man, fellow passenger Roger Hewitt. Unfortunately for Evelyn, she is with Hewitt when Peter Yates comes blundering in to address the wrong man as “Mr Gorman”; and even more unfortunately, Yates tells Gorman about his little mistake when he finally catches up with him in the hold, where he is checking his animals.

One of the truly curious aspects of Murders In The Zoo (at least to me) is its attitude to its animals. Gorman, clearly, is devoted to the wild beasts he has captured, although not always in a good way, as we shall see; but in any case, the admiration, kindness and affection he displays towards them is clearly genuine. Oddly, this is presented, not as a redeeming feature in Gorman’s character, but as further evidence of his psychosis.

It is Peter Yates, who reacts to the animals with a mixture of fear and loathing, and regards them purely as objects to be exploited, who is tacitly held up as an example of the correct response; a stance I find deeply puzzling, not to say offensive. (And frankly, the idea of Peter Yates as vox populi is something we should all find offensive.) Thus when Yates finds Gorman with a chimp in his lap, wiping its eyes and nose with a hankie and worrying that it has a cold, the expected audience reaction is not, evidently, “Awwwww! Monkey!”, but a significant tap on the forehead.

(Truthfully, this is a charming moment; Atwill looks like he’s having a blast playing with the chimp.)

As the animals are settled into the zoo, Professor Evans, its head curator, explains to Gorman that the zoo is in deep financial trouble, having had its budget cut yet again. (We see that the zoo does not charge admission. Presumably if it did, it would lose most of its Depression-era visitors, who run tame there every day.) Yates suggests a fund-raising dinner, an idea that Gorman, with his own agenda in mind – and that alarming glint in his eyes – immediately seizes upon, offering to organise the whole thing himself. Gorman then presents to Evans’ associate, Dr Jack Woodford, a precious specimen indeed: a green mamba, a species of snake for which an antivenene does not currently exist.

We now move into the portion of Murders In The Zoo that is closest to my heart. Some time after this, Woodford’s mamba will apparently escape, causing the death of one man before evading the squad of people searching for it. One wonders, given this plotline, why with an entire global serpentarium to choose from, the writers picked perhaps the most conspicuous snake there is to play the role of this elusive killer.

The green mamba is one of the most spectacularly beautiful snakes in the world. The western green mamba tends to be either a yellowy- or an olive-green, while the eastern variety is most often a vivid emerald or grass-green colour. Green mambas are slender, elegant and graceful snakes, usually around six feet long, but sometimes eight or more. It is, therefore, somewhat unlikely that a person could be in a confined space with one and not know it.

The green mamba is equally unfitted constitutionally to be cast as this film’s secret killer. Unlike their more famous cousin, the black mamba, green mambas are shy and non-confrontational. They are also predominantly arboreal – meaning that no green mamba would be found where this film’s specimen eventually is. Furthermore, these species are only one-tenth as toxic as the black mamba – although that’s quite toxic enough, if you do manage to provoke one to bite you. If not exactly, “The swiftest-acting venom there is”, green mamba bite can certainly be fatal; and it is true enough that when this film was made, there was no antivenene.

However, that’s about as close as the writers of Murders In The Zoo ever get to accuracy…unless we are to take at face value Gorman’s statement that this specimen of mamba is “a new variant” that he “picked up in India”. “New” is right: when it is eventually produced for our viewing pleasure, we find that the role of the mamba is being played by a perfectly harmless python of about four feet in length.

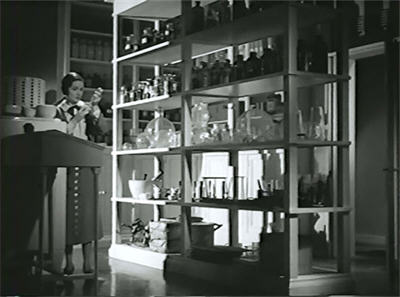

Handling of the, ahem, deadly mamba falls to Dr Jack Woodford, a biochemist whose speciality is the development of new anti-venoms, and his assistant, Jerry Evans, who is also his fiancée. Although they are nominally the film’s romantic leads, it is Jack and Jerry’s expertise in herpetology and toxicology that really matters to the story. We see them working together in their laboratory, extracting venom from their specimens and examining the mamba; two activities that will prove of more than a little importance by the end of the film.

Western………………………………………………………………………….Eastern

In contrast, the couple’s personal relationship is very lightly sketched, just a nod to the conventions and, perhaps, like the inclusion of Peter Yates, an attempt at lightening the film a little. If so, it’s a far more successful one. It is nice, though – and three years before The Walking Dead, too! – to have a pair of scientists as our young lovers. And naturally, since they are both scientists, we hear them bemoaning the fact that they can’t afford to get married.

The prospect of the fund-raiser and the zoo’s financial recovery brings a light to Jerry’s eyes: “You know what it would mean?” “I’ll be able to go on with my laboratory work,” replies Jack promptly. Jerry barely has time to assume an expression of amused dismay before he adds, “And you’ll have to stop stalling about marrying me!”

(Later, Jack tells Jerry that he, “Won’t be home for dinner.” He’s probably just boarding with the Evanses, but it does sound for a moment as if Jack and Jerry are shacked up!)

Eric Gorman is as good as his word, organising to have the wealthy and the elite attend a dinner at the zoo, in which tables are set out down the middle of the Carnivore House. (My instinctive reaction to that arrangement is always, “PEE-YEW!!”…but, you know, suspension of disbelief, and all that…) The guests find their places at the tables thanks to some adorable cartoon animal place-cards – Jane Darwell and Samuel S. Hinds are, unbilled, amongst them – and Roger Hewitt finds to his surprise and pleasure that he is seated next to Evelyn Gorman. His enjoyment of the situation is abated, however, by the subsequent discovery that Gorman is seated opposite the pair of them, albeit still being genial and, evidently, suspecting nothing.

Who’s a pretty boy, then?

Some of the most painful Peter Yates schtick occurs here, and everyone is, surely, deeply grateful when an interruption occurs in the form of a shriek of pain. Well – everyone, that is, but Roger Hewitt, who has lurched to his feet with his face contorted in agony. The dinner guests react in alarm and dismay as he collapses. Professor Evans insists hurriedly that Hewitt has simply fainted, and calls for calm.

Hewitt is carried out into the next room, where Jack Woodford examines him, noticing that his leg is badly swollen. He cuts open the leg of Hewitt’s trousers and, sure enough, finds evidence of snakebite. The spacing of the fang-marks puzzles Jack, but Gorman points out that a mamba bite would be that wide. Jack sends Jerry to check on their specimen, as Gorman adds grimly that if the mamba is responsible, there’s nothing to be done for Hewitt. “He’ll be dead within five minutes.” Jerry returns with the news that the mamba’s cage is indeed open, and the snake missing…

All of this has been overheard by one of the guests who helped carry Hewitt in, and he is swift to report back to the others, shouting, “Get away from that table! There’s a poisonous snake under it!” Yes, an eight-foot long, bright emerald green one; easily overlooked.

Oh, I know, I know….but really, if you were going to write this kind of story, why a green mamba!? Brand recognition aside, why wouldn’t you pick something like a krait? Depending on the species, they are small, and inconspicuous; they’re deadly venomous, and they get aggressive at night. And they’re found in India and French Indochina. No fun in being sensible, I guess.

Like this little guy…

Meanwhile, Jack Woodford examines the snakebite on Hewitt’s leg. Reflective of this film’s vintage, he then proceeds to do most of the wrong things. He puts tourniquets tightly around both ends of the bite-zone, and he cuts the wounds open. Thankfully, however, he makes no move to try and suck the venom out, although possibly only because Hewitt is already dead. Instead, he extracts what he can by syringe, and keeps it for later analysis. He also takes formal measurements of the bite.

(The correct response to snakebite depends on the venom: pressure bandages are recommended for elapid bites [i.e. neurotoxins] but discouraged for viperid bites [i.e. cytotoxins]; know your indigenous species, people! There are no vipers in Australia, which is why we tend to generalise here about the use of pressure bandages. Mambas are elapids, although their venom is particularly dangerous because it is a mixture of neurotoxins and cardiotoxins. Snakebites should not be cut under any circumstances; this does nothing but significantly increase the danger of serious infection. Most studies indicate that trying to suck the venom out, either manually or with a commercial extractor, is probably pointless. Complete immobilisation of the patient with the bite-zone below the heart is critical. Here endeth our community service announcement.)

Jack is recording his findings when Evelyn Gorman enters the room silently, staring down at Hewitt’s body in a mixture of horror and despair too profound for utterance. When Jack notices her, he puts an arm around her shoulders and gently leads her away.

Out in the Carnivore House, the numerous reporters and photographers invited by Peter Yates have sprung into action, ignoring Jerry’s pleas that this negative publicity will ruin the zoo. Gorman takes Evelyn from Jack, and then proceeds to turn the knife, pointing out that any chance of outside help for the zoo has now been ruined, and adding that the mamba’s escape is Jack’s fault: “Gross negligence!” Jerry immediately jumps to Jack’s defence, retorting that she saw him put the snake away and lock its cage; but of course, since Jerry is Jack’s fiancée, no-one listens to her.

Except, perhaps, Evelyn Gorman.

One of the clearest signs that Murders In The Zoo is a pre-Code movie is its attitude towards Evelyn. It is never quite clear whether or not Evelyn was really involved with the unfortunate Taylor, as Gorman himself believed. Telling Hewitt of the incident, and of her belief that Gorman was responsible for Taylor’s death, Evelyn says only, “He tried to kiss me”, which may be whitewash, or may be the absolute truth; Gorman clearly wouldn’t need Evelyn to be guilty to believe her guilty.

But although Evelyn may indeed be an adulteress, and a repeat one at that, the film shows nothing but compassion for her, as a woman trapped in a relationship with a sexual psychopath, and understandably looking both for comfort and for a way out. (When Evelyn’s reaction to Hewitt’s death makes their relationship evident, Jack shows only the deepest sympathy for her.) Sadly, no happiness awaits Evelyn Gorman; but when she meets her fate, there is not the slightest sense that the film feels that she deserves it, that she “asked for it”; the moment is one of horror only.

It is when the Gormans arrive home after Roger Hewitt’s death that Eric Gorman finally reveals himself fully in his nightmarish true colours. Evelyn, eerily calm, says, “You killed Roger. That’s why you sat opposite us.” Gorman laughs off the accusation, asking Evelyn if she thinks he was carrying an eight-foot mamba on him? – but she is not to be dissuaded from her conviction.

And in the face of Evelyn’s fear of him, her loathing, her hatred, Eric Gorman begins running his hands over her body.

“I have never wanted you more than I do now,” he tells her heatedly.

In this extraordinarily disturbing sequence, Murders In The Zoo is again the very essence of a pre-Code film. A year later, no scene as frank as this would have made it onto American cinema-screens; both its implications and its particulars would have put it beyond the pale.

As Evelyn struggles with her husband, overcome by a mixture of revulsion and terror, Eric becomes more and more aroused, his unwelcome caresses becoming likewise more and more intimate. (Lionel Atwill all but puts his hands squarely on Kathleen Burke’s breasts here, making the gesture but then sliding them aside at the last instant. As for Evelyn / Kathleen, you can almost see her flesh crawl.) Finally, Evelyn throws her love for Roger Hewitt in Gorman’s face, and their plans to run away together. “Now will you let me go?” Needless to say, this only increases Gorman’s excitement. “I wonder why I love you so…?” he murmurs.

“I hate you!” Evelyn cries and, tearing herself away, runs for her room. Gorman stares after her, a smile sliding across his face. He walks up to that door and tries to open it, but naturally it is locked. Confronted by this situation, Gorman shakes the handle for a moment, then calls out to Evelyn that he will be back in five minutes – and that he will expect to find that door open…

(And let us not forget, people, that when this film was made, Eric Gorman had every legal right to make that demand.)

Evelyn’s first impulse is to start packing. Then the oddness of Gorman’s retreat strikes her, and she begins to wonder exactly what could be more urgent to him than what he was doing. Evelyn’s room and Eric’s study are corner-opposites; Evelyn goes out onto her balcony, straining to see what her husband is doing in there and watching in growing suspicion as he carefully removes something from his pocket and locks it away in his desk. Gorman then switches off the light and leaves. Evelyn clambers across the balconies and climbs into the study through the window, breaking into that desk drawer to discover her husband’s secret. What she finds there is, surely, one of the most wonderfully warped murder weapons ever dreamed up by a screenwriter: the severed head of a second green mamba, which Gorman “loads” from a vial of mamba venom.

Evelyn instantly realises the significance of her find, bundling up the deadly object with great care. Gorman, meanwhile, is knocking on his wife’s bedroom door – which he soon forces open. It takes him some moments to realise that Evelyn is, in fact, gone; where she must have gone; and what she found and confiscated on the way; and by that time, Evelyn is out the front door and on her way to the zoo – and Jack Woodford.

Sadly, this wonderful example of quick-thinking and tactical cleverness wins no reward for Evelyn. Gorman guesses where she is going, and while she is identifying herself at the front gate and waiting for the security guards to admit her, he is secretly climbing over a wall. So it is that Evelyn never reaches Jack: instead, Gorman heads her off – at the alligator pit.

Ah, the alligator pit! I am, of course, very fond of the lion cages with the spaced-out bars, but I love the alligator pit even more. There’s a wooden bridge over the water here, one thigh-high to your average adult, and about two feet above the surface of the water. The pit also reaches so close to what is laughingly referred to as its “fence”, that a small child with a stick is later able to lean over it and fish something out of the water. The only wonder here is that Roger Hewitt’s death was, apparently, the first reptile-related one in the history of this zoo. I would very much like to meet and shake the hand of the person who designed this particular exhibit – if, that is, I could convince myself they have any hands left…

And so the Gormans meet in the middle of that wooden bridge. Eric wrenches the mamba head away from Evelyn and pockets it carefully – and then blithely suggests to Evelyn that they just go home. From his point of view, by murdering Hewitt he has simply shown Evelyn how very much he loves her. This line of argument provokes her into further cries of hatred and disgust, which of course only serve to make her husband more amorous. But then Evelyn changes her tune, declaring Gorman a murderer and announcing her intention of making sure that everyone knows he is. The smile finally wiped from his face, Gorman takes one long, final look at his wife – and then tips her over the edge of the bridge…

And after glancing around briefly to make sure that no-one has heard anything, Gorman leans on the railing and watches composedly as about a dozen thrashing alligators, one doing a death-roll, solve his little marital difficulty for him.

(This is a staggeringly constructed scene. It is filmed medium-long, and in one shot; and as whoever it is – presumably not Kathleen Burke – falls from the bridge, you can see a couple of alligators raise their heads from the water.)

And so it is that just as Professor Evans and his employees were thinking that things couldn’t get any worse, a small boy pulls a piece of Evelyn’s dress out of the alligator pit. (“Looks like someone got et,” observes the kid judicially.) Evans and Woodford then get exactly the news they don’t want from the security guard who admitted Evelyn. Gorman is asked in to identify the torn cloth and, after an affecting display of distraught innocence, and recognising that attack is the best form of defence, he turns on his former colleagues, accusing them, Jack in particular, of Evelyn’s death and Hewitt’s, too – “Your carelessness! Your stupidity!” – and threatening criminal charges. He also severs all ties with the zoo.

Though of course, if there’s one problem with using a snake, or even a part of one, as your murder weapon, it’s that the person most likely to catch you out is your friendly neighbourhood herpetologist – particularly when he’s just been accused of criminal negligence.

In the wake of the twin tragedies, the zoo is shut right down, and the animals begin to be shipped out to other locations. With all funding cut, most of the staff is laid off, too, with those few remaining doing what they can to look after the animals that are still there. In a deliciously fitting moment, Peter Yates is given the job of mucking out the empty cages (he should be right at home there); so that it is he who, almost literally, stumbles over the missing green mamba, hunkered down under some straw. Yates’ hysterics bring Jack Woodford to the scene, and he succeeds in securing the snake.

Jack’s subsequent inspection of the animal brings to light a curious fact: namely, that its fangs are too close together to have caused the bite-mark on Hewitt’s leg. We actually get to see Jack measuring the gap between the mamba’s fangs – and he is able to do this because in this scene, he and Jerry are handling a rattlesnake! I have no idea if Randolph Scott had experience handling snakes, or if this was just a case of a young actor not daring to refuse to do as he was told; either way, the decision to show the audience a real venomous snake, and some real fangs, is yet another of this film’s surprises. And good on Gail Patrick for pitching in, too…although she does get the safer end of it.

(The fact that someone cared enough to insist on this bit of verisimilitude does give me some faint hope that the mamba’s final scene was faked.)

The mamba is replaced in its cage (having reverted to python-dom in the meantime, suggesting that the film-makers did give at least a little thought to their actors’ safety) and a puzzled Jack checks his notes. This snake has a bite-width of 28 mm; but the snake that bit Hewitt had a bite-width of 36 mm. (Both of which are far too wide for the snake to have been a mamba, for which you would expect something in the range of 10 – 15 mm.) It couldn’t be the same snake. Yet Hewitt was bitten by a mamba, as the venom analysis proved.

And who is the most likely person to have a second green mamba in his possession?

By this time, Jack, like Evelyn before him, has contracted a clear case of (if Paramount will forgive me using a Warner Bros. expression), “I don’t know how youse dunnit, but I know youse dunnit.” In pursuit of an answer, Jack phones Gorman, who makes snotty remarks about seeing him in court; but when Jack effectively tells him to bring it on, the wary Gorman finally agrees to come to the lab…a certain item in his pocket. There, Jack shows him his findings, and accuses him openly of having a second snake; adding that he thinks that is what Evelyn was coming to tell him on the night she died. And then he makes the mistake of turning his back.

Swiftly, Gorman strikes, inflicting one, two, three bites with the severed but still deadly snake head. Jack cries out in agony and collapses…

Gorman gets busy, staging the scene to make it look as through the mamba escaped, and that Jack killed it with a poker, but was bitten before he could finish it off. So that when Jerry arrives, carrying a dinner-tray for Jack, she comes across the aftermath of a third tragedy—

—except that Jack is still alive. Jerry rushes from the room, speaking hurriedly of the new antitoxin that Jack had just that day succeeded in producing.

“Antitoxin!?” repeats Gorman, torn between disbelief and indignation.

Gorman follows Jerry into the next room, where she is preparing an injection; and, now desperate enough to get his own hands dirty for a change, tries to stop her. But Jerry is desperate too. Reading Gorman’s intentions in his face, she instantly picks up the mortar from a nearby mortar-and-pestle and clocks him a beauty, before running back to the lab, locking the door to keep Gorman out, and giving Jack the life-saving injection.

Now in a panic, Gorman bolts, giving Jerry the chance to take further action. On an inside line, she gets Peter Yates and tells him frantically to call the police. In his one redeeming moment, Yates instantly contacts the main guardhouse, where the head guard sets off the zoo’s alarms, including an automatic summons for the police.

Zoo employees, guards and policemen begin to converge. Gorman darts about in a panic, trying to evade them, and finally finds himself in the Carnivore House. There, he tries to create a diversion – pretty damn successfully, one would have to say – by pulling the master lever and letting all the big cats out of their cages; an act that does rather dissuade Gorman’s pursuers from going in there after him.

But then Gorman is arrested by the sight of the cats attacking one another; and instead of making good his escape, he stands there watching them, that familiar glint in his eyes.

So what happens next serves him right. That is, it serves him right anyway, but— Oh, you know what I mean!

Before long, the cats lose interest in each other and turn on Gorman. This breaks the spell holding him, and he runs out and into the next cage area, where he takes refuge in one of the cages, shutting the door to bar the cats out.

Except the cage that he is in isn’t empty. It contains a very large reticulated python…and it is pissed.

He that liveth by the serpent shall perish by the serpent.

And Murders In The Zoo has one last surprise for us here, as, despite some fudging (arms and a hat conveniently thrown across the face, and so on), in some shots it clearly is Lionel Atwill interacting with that python; and by “interacting” I mean, getting up close and personal with an extremely large and dangerous snake in a way that I doubt he ever really wanted to…

As a herpetophile, it is hard to know whether to steer people towards Murders In The Zoo, or away from it. Anyway, I guess I’ve said enough about the various issues, so people can make up their own minds about that. This film really is a very odd mixture. The bits that work, work brilliantly; and the bits that are painful, are so very, very painful…

Perhaps unusually, I find that one of the real strengths of this film is the acting. It’s a classic psycho role for Lionel Atwill, of course, and his contribution is one of this film’s main pleasures. At the same time, both Randolph Scott and Gail Patrick are very likeable here. I mean, granted, playing a pair of snake-wrangling scientists, they had me at “Hello”; but both actors give nicely judged, credible performances that help to balance out Lionel Atwill’s extravagance, and to sell the film’s absurdities. Even at this very early stage of the game, Randolph Scott was projecting the kind of sincerity that in the following decades would help him build a significant career. Gail Patrick, meanwhile, is extremely well-treated by this film’s script, being given the chance to create a character who is loving, courageous, and level-headed in an emergency. Kathleen Burke as the doomed Evelyn Gorman is the film’s other stand-out. Intelligently, the actress underplays most of her early scenes, getting quieter and more reserved in moments of crisis, so that her subsequent hysteria when her husband actually touches her has all the more impact.

For anyone with an interest in film-making before the enforcement of the Production Code, Murders In The Zoo is unmissable; its frank sadism, physical and sexual, is exactly the kind of thing that Joe Breen and his minions most despised, and went out of their way to expunge. Intriguingly, with the enforcement of the Production Code, Paramount essentially gave up making horror movies for the next decade. The studio made one more in 1933, Supernatural (the Halperins’ follow-up to White Zombie, also starring Randolph Scott); and after that, apart from The Cat And The Canary and The Ghost Breakers – which were viewed as vehicles for Bob Hope rather than as horror movies, or even horror-comedies – and a little B-movie dabbling in the early forties, the studio did not produce another significant horror film until 1944, with The Uninvited and The Man In Half Moon Street. Paramount was never a “home” to horror in the way that Universal or RKO was, of course, so it is hard to know whether this hiatus was just a coincidence, or whether (as I like to think) it was a deliberate response to the new restrictions of the Production Code; evidence of the studio’s determination to do a thing properly, or not to do it at all.

….*burp*….

Footnote: I don’t know what it was about Lionel Atwill’s films, but they seem to have brought out some peculiar tendencies in the studio advertising people. Remember how Doctor X was promoted on its poster as, “The outstanding love-mystery of all time”? Well, that middle poster I’ve reproduced at the top of this review describes Murders In The Zoo as, “Scaling the Shrouded Heights of Terror, yet Lighted by the White Flame of Great Romance”.

Eh!?

Want a second opinion of Murders In The Zoo? Visit 1000 Misspent Hours – And Counting.

Pingback: Captive Wild Woman (1943) | and you call yourself a scientist!?

Pingback: Doctor X (1932) | and you call yourself a scientist!?

Was Jerry the first example of the “female scientist with an androgynous name” trope? Did they have a line like “I wasn’t expecting… a WOMAN?”

LikeLike