“Life is such a miraculous, delicate thing. What if this poison were to upset the balance? – and instead of a normal, healthy child, ours were to be born a—a—“

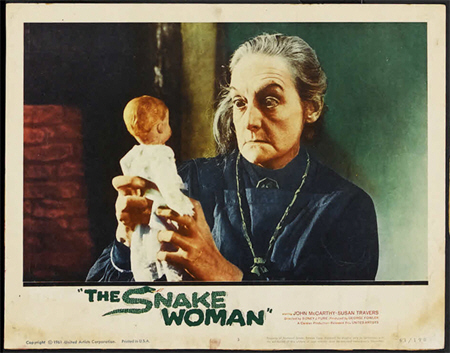

[Also known as: Terror Of The Snake Woman]

Director: Sidney J. Furie

Starring: John McCarthy, Geoffrey Denton, Elsie Wagstaff, Arnold Marlé, John Cazabon, Hugh Moxey, Stevenson Lang, Michael Logan, Dorothy Frere, Jack Cunningham, Frances Bennett, Susan Travers

Screenplay: Orville H. Hampton

Synopsis: Bellingham, Northumberland, 1890. Dr Horace Adderson (John Cazabon), a herpetologist, is working upon developing a venom-based treatment for insanity—using his own wife, Martha (Dorothy Frere) as a test subject. As Adderson goes to give her an injection, Martha protests violently, fearful of what the treatments might be doing to her unborn child. Adderson ignores her protests, forcing her compliance by reminding her of her earlier mental problems. No sooner has the injection been given than Martha’s contractions begin. Adderson hurries away to summon the local doctor, Murton (Arnold Marlé), and a midwife. However, so bad is the scientist’s reputation in the village that the only midwife who will attend Martha is Aggie Harker (Elsie Wagstaff), the local “wise woman”. Martha’s labour is difficult, and Murton fears that she will not survive it; he is puzzled by her condition, which suggests the action of a neurotoxin. Meanwhile, the child is born icy cold. Murton is about to break the bad news when the “dead” baby cries softly. Immediately, Aggies declares it to be “a thing of evil”. Ignoring her, Adderson points out the child’s strange, unblinking eyes, which Murton attributes to improperly developed eyelids. Martha demands to see the child, but no sooner is it placed in her arms than she dies. Instantly, Aggie snatches up a pair of scissors and tries to kill the baby, but Adderson overpowers her. Murton tries to give the hysterical woman a sedative, but she breaks away and runs from the house. Bursting into the village pub, Aggie tells those present about the strange events at the Adderson house. As it accepted amongst the local people that Aggie has second sight, her fears are taken seriously. The constable (Jack Cunningham), hearing that Martha Adderson is dead, agrees to investigate, while some of the local men, including Barkis (Michael Logan), who owns the pub, decide to go with him. Hearing the mob’s approach, Murton asks Adderson if there is anywhere the baby may be taken for safety. Adderson suggests an isolated hut occupied by an old shepherd (Stevenson Lang). Murton makes his escape with the baby by the back door, as Adderson goes to confront the invaders. The constable insists upon seeing Mrs Adderson, while Barkis and the others look at Adderson’s snakes with loathing. The constable returns with the news that not only is Martha dead, but there are injection marks on her arm. Aggie then demands to know where the baby is. Adderson replies that Dr Murton took her away, only to be accused of killing her, too. The mob then turns violent, smashing all of the snake tanks and setting fire to the house. When Adderson tries to intervene, he is knocked down. In the aftermath, dazed and unsteady, he is bitten by one of the snakes, and collapses as his house goes up in flames. At the shepherd’s hut, Murton succeeds in persuading the old man that he will only need to care for the child until Adderson comes for it in the morning, adding that he cannot care for her himself, as it is the eve of his departure for Africa… It is almost twenty years before Murton returns to the village of Bellingham. He seeks out the old shepherd, learning to his dismay that the girl, named Atheris (Susan Travers), disappeared some years earlier—and that at the same time, Bellingham began to be plagued by mysterious deaths…

Comments: The only name that leapt out at me while I was watching the credits of The Snake Woman was that of screenwriter, Orville H. Hampton—although not in a good way. Mr Hampton had a long and on the whole successful, if not brilliant, writing career, one highlighted by an Academy Award nomination; but the last time he and I crossed paths, it was as a result of his re-shaping of the screenplay that would become Mesa Of Lost Women. Now, that film being what it is, it isn’t easy to determine how much of it can be blamed upon Mr Hampton; in fact, there’s a very real possibility that his contribution actually improved it. Such is not the case, however, with The Snake Woman. This film is bad in every respect, but chiefly with regard to its screenplay, which is – with the exception of one or two touches that I am quite prepared to believe were accidental – a mindboggling piece of writing. And not least amongst its virtues is the opportunity for a brand new drinking game: just try knocking one back every time someone uses the word, “Ridiculous!” It’s almost as if Orville Hampton’s subconscious was trying to tell him something.

This is the only piece of alternative advertising art I’ve been able to find for this film; so, enjoy!

The action of The Snake Woman takes place in England, in a tiny village called Bellingham, in Northumberland; and its events begin in the year 1890. I tell you this quite plainly, because otherwise you would be excused for assuming that this film was set in some kind of weird alternative universe, where concepts such as “logic” and “cause and effect” simply don’t exist. It opens with a piece of narrative from someone who is never identified, and from whom we never hear again (although it may be actor Geoffrey Denton, either in or out of character, whose contribution is one of the film’s few positive qualities), which us that tells no “official record” exists of the “strange happenings” that afflicted this village at the turn of the century.

The narrator then offers a beautiful piece of chop-logic, informing us that the story was handed down by the villagers, who preferred to forget about what happened. The reason for this collective piece of selective memory will become apparent before too much longer. Suffice it to say that it has nothing whatsoever to do with “legends” or “curses” or “snake-girls”…

The first person we meet is Dr Horace Adderson, a scientist, a herpetologist, and a father-to-be…very much in that order. (Yes, that’s right: a herpetologist called ‘Adderson’; sums the film up, really.) Dr Adderson, amongst his many other sterling personal qualities, which will shortly be illustrated for us, is a Victorian husband par excellence. He has no interest whatsoever in anything his wife thinks, or feels or wants; and he will take her subsequent death, and the apparent death of his newborn daughter, without so much as a shrug. However, when we first meet Dr Adderson, in a room surrounded by glass tanks containing his specimens, he is intent upon something that will make his various domestic shortcomings seem minor in comparison.

Cries of pain come from the next room. Adderson looks vaguely irritated at the interruption, but moves towards a tank containing a cobra, removing it and milking it. (Mysteriously, we are able to see only his hands until the animal is returned to its tank.) Adderson then takes some of the venom up in a syringe and heads for the next room, where a woman lies huddled up in bed. No sooner does she see the syringe, than she gives a gasp and shrinks back in her bed.

…and computer graphics from 1910.

“Now, now, Martha, there’s no sense in your carrying on like this—and there’s no use screaming!” remarks Adderson matter-of-factly. “Let’s get this over so that I can return to my work!”

Martha continues to object, insisting that no-one can no know what all that venom in her veins will do. Adderson might make it through the subsequent loss of his family without blinking, but this implied slur on his research gets an immediate reaction. “Of course I know!” he bridles, arguing that snake venom has already been used to treat, “Haemophilia, epilepsy, rheumatism, hypertension, even cancer!” – and that he, Horace Adderson, will soon be famous for using it to cure mental illness, “When they all said you were hopelessly insane!”

“But what about the baby?” wails Martha.

Good lord, where do we start with this!? So, did Martha develop her mental illness after her marriage – I mean, you wouldn’t be surprised, would you? – or did Adderson marry her because he saw her as a good test subject? Did she get pregnant before or after the venom treatments began? Did he for a moment stop to think that pumping a pregnant woman full of cobra venom maybe wasn’t the best idea he’d ever had?

Well, we can answer the last one: no, of course not. “The baby?” Adderson repeats blankly when Martha protests, as if that little detail had just slipped his mind. He is, in fact, momentarily caught by Martha’s fears about what the venom might be doing, but then waves them away – “That’s ridiculous!” – and suggests that her concerns are merely an expression of her mental state, and thus proof she needs another venom shot right away. Martha’s not having any, though, insisting that until the baby comes, she’s willing to risk a relapse; but Horace isn’t, telling her frankly that she’s not just his wife, she’s the vindication of his work—and that’s worth more than any child. However, it is her husband’s suggestion that the baby might otherwise inherit her mental illness that wins Martha’s reluctant co-operation…and in goes the needle.

Yup: she’s from 1910, orright…

No sooner has the injection been given than Martha cries out, clutching her abdomen. Adderson hurries away to fetch help; and while he does bring the doctor, a German émigré called Murton, the only midwife who will come to Adderson’s house, thanks to his evil reputation – well, mostly thanks to his snakes – is the local “wise woman”, Aggie Harker.

(Of course, one does wonder, in a village of only two hundred people, how many midwives there are.)

Aggie Harker. Oh, dear lord, Aggie Harker. Elsie Wagstaff’s performance here really has to be seen to be believed. She shrieks, she cackles, she raves about, “EEE-VIL”, and she does her best to murder a newborn, and then incites a mob to violence—and then the film has the gall to present her as being on the side of the angels!

When the delivery is over, and Dr Murton must warn Adderson that his wife has, “Barely a flicker of life”, and that his daughter, “Never had a chance”, Aggie merely stalks around looking ominous; but after one glance at the baby, with its wide-open eyes, Aggie pronounces, “It is evil! It has the eye! It is the devil’s offspring!”, and the game is on.

Meanwhile, Dr Murton is puzzling over Martha, who is reacting as if she had been exposed to a neurotoxic poison. Adderson harrumphs a bit, but says nothing. Martha begs weakly to see the baby. Murton is trying to break the bad news to her when the baby softly cries, much to everyone’s astonishment. Murton protests that it is impossible, that its blood was cold! “Cold…blood?” mutters Martha (who, we observe, seems a lot more with it mentally than her loving husband would have us believe).

“I won’t touch it! It is EEE-VIL!” announces Aggie (who really does give Richard Burton a run for his money in this film). Murton finds the baby icy cold, but undoubtedly alive; its eyelids are undeveloped, so that it cannot close its eyes. Martha again demands to see the baby, and Murton carries the child to her; but no sooner has Martha taken a single look than she gasps and dies.

The village wise woman. Which tells us everything we need to know about the village.

Of course, this goes down a treat with Aggie, who has already heard Adderson musing, “Like a reptile!” Seizing a pair of scissors, she rushes at Adderson, who is holding the baby, crying, “The child is evil! It has the eye! One look killed the mother! It will curse us all! It must be destroyed!”

Although he stops her harming the baby (it mysteriously vanishes from his arms during the few seconds it takes Aggie to snatch up the scissors), Adderson cannot control Aggie. Murton comes towards her with a sedative – again with the needles, huh? – and grabs her arm, but humiliatingly enough for both men, Aggie manages to throw them off. Indeed, Adderson hits the wall so hard, he is dazed by it! I mean, okay, neither Adderson nor Murton is exactly a spring-chicken, but really…

Aggie escapes the house, running towards the village and seeking help at – where else ? – the pub.

Ah, the pub! – where we’ve already met Barkis, the landlord, and Constable Alfie. Aggie bursts in, shrieking about, “EEE-VIL!!” and “MURDER!!” and “A CURSE ON US ALL!!”; all of which is taken absolutely at face value, on the logical grounds that everyone knows Aggie has the gift of sight.

Aggie gives her version of events, telling those present that Martha Adderson is dead, which she blames on the baby, and that so would the baby have been, if only they hadn’t stopped her! – to which public confession of attempted infanticide, the constable responds, “If someone’s dead, it should be investigated.” So—the near-scissor murder of a baby is a minor detail, but a Victorian woman dying in childbirth is a matter for the police? Hmm.

Anyway, it soon turns out that the constable has had his suspicions about Adderson for some time – for the heinous crime of snake-handling, as far as we can judge – and is glad of an excuse to barge in and harass him.

Horace Adderson: husband, father, herpetologist, criminal psychopath…

Between them, Barkis and Aggie goad everyone else in the pub into forming a mob; Aggie gives her best Margaret Hamilton cackle at this outcome. The villagers strides purposefully in the constable’s wake, after briefly stopping to – oh, good lord! – light some torches.

Meanwhile, Adderson is wondering whether Aggie might not be right? Murton instantly protests – “Ridiculous!” – but just as we’re thinking we might have found the one decent human being in this idiotic tale, he disabuses us.

“You are a research scientist, and so am I!” Murton declares (yeah, thanks for that). “Can you imagine the excitement when the scientific world learns that a cold-blooded child was born alive? It is of the utmost importance to human knowledge that your child’s life be preserved at all cost!”

(Uhhhh…yeah. Apparently these two “research scientists”, one of whom is a herpetologist, don’t know that cold-blooded animals don’t actually have cold blood!)

Reasons aside, means for preserving the child’s life become a matter of urgency when the mob rolls up outside. Adderson sends Murton away with the baby, directing him to take it to an isolated shepherd’s hut, from where he will collect it in the morning.

Yeah, right.

Anyway, as Murton exits the back door, Adderson politely invites The Mob into his house through the front door. As Constable Clod goes to inspect Mrs Adderson, Barkis and the others react with loathing to the sight of the snakes, which they take as evidence of Adderson’s perverted and/or criminal tendencies.

“Now, Martha…you really must get over this ridiculous business of having your own opinions!”

Barkis: “There’s something strange about a man consorting with wicked reptiles like these!”

Adderson: “There’s nothing strange, and snakes are not wicked. They’re much-maligned, highly intelligent, useful creatures!”

Barkis: “These slimy monsters! Let’s kill the slimy things, every last one of them!”

As you can see, I was in quite a bind here. I hope I shall be forgiven if I confess that, just for a few moments, I found myself sympathising with Mr Experimenting-On-My-Insane-Pregnant-Wife. At any rate, I’m sure I shall be, when I also confess that at this point I zoned out for a minute, while I indulged a fantasy about a meeting between dear Mr Barkis’s skull and a baseball bat.

The constable then comes in from examining Mrs Adderson, exclaiming about marks on her arm, which Barkis is sure are not needle marks at all, but snakebites. (Why is that worse?) The constable does make a feint towards arresting Adderson, but when in response to Aggie’s shrieks, Adderson explains that Murton took the baby away, he is immediately accused of her murder, too. (So it’s okay for Aggie to kill the baby, but not Adderson?) Barkis then leaps into action, smashing the snake tanks – NOOOOOOOO!!!!!! – while the torch-bearers get busy on the rest of the house.

And what is the constable doing while all this is going on? Helping. Mostly by warning the mob that the fire is getting out of control, and they should leave. So they do; and the constable is next seen outside, directing the torching of the grounds around Adderson’s house.

Meanwhile, the dazed and beaten Adderson, instead of fleeing, tries to help his snakes…and one of the ungrateful little buggers bites him. He collapses, as the flames build…

Aggie Harker: just the kind of soothing personality you want around when you’re in labour.

(A word here. The Snake Woman features many real snakes, making the scene of the lab-trashing doubly upsetting. At one point, Adderson does lift a very limp snake; and there are shots in which the lives ones are rather too close to the flames. However, given that all the snake-whacking is carefully kept offscreen, and that in the one later scene in which a snake is supposedly killed, it can be seen still moving, I’m prepared to give this film some benefit of the doubt and hope that the “dead” one was a fake.)

Anyway— Here we get at the real reason that the villagers were rather loath to discuss these “strange events”. Nothing to do with “curses” or “legends”, really; just a touch of arson-homicide. Arson-herpicide, too, but I’m probably the only one who cares about that.

While this is going on, Murton is up at the shepherd’s hut, thrusting the baby upon the bewildered cottager. When the shepherd, not unreasonably, demands to know why Murton can’t look after it himself, the doctor tells him (as he told Adderson, in one of the film’s clumsier expository moments) that he is leaving for Africa in the morning.

Actually, as excuses go, that’s a pretty good one. Left with little choice, the reluctant foster-father takes the baby in. We next see Murton being sent on his way amidst handshakes and waves from the nice friendly people of Bellingham—including the constable! Murton doesn’t think to inquire about Adderson’s fate, even though upon giving the baby to the shepherd, he insisted that, “Dr Adderson is in great danger!”; and the villagers – perhaps not surprisingly – don’t raise the subject either. The final moment here, however, is dear old Aggie glowering at the departing medico.

We then get one of The Snake Woman’s highlights, namely its handling of the passage of time. In a quick jumble of shots we have the shepherd’s dog reacting to the baby’s presence; a child of seven or eight; some panicky sheep; a snake moving through the undergrowth; the shepherd finding his dog dead; and a white-haired Murton greeting the shepherd with, “Why, it must be twenty years!”

“Now, granted, your child is a hideous freak of nature; but just think of the publications we’ll get out of this!”

Yes, as it turns out, after nineteen years of “successful research” (unspecified) in Africa, Dr Murton has returned to Bellingham to live out his retirement. And really, why wouldn’t you? It’s so cheerful there, and so welcoming to outsiders. Murton eventually thinks to inquire after the girl. He hears of Adderson’s death; the girl’s effect on animals; and that the shepherd saw fit to bestow upon her the inconspicuous name of “Atheris”, which he got out of one of Adderson’s books. (Which survived the fire? Hmm. By the way, Atheris is a genus of African viper.) Murton also hears to his dismay that the girl disappeared several years earlier. The shepherd remarks, of the ruins of Adderson’s house, that Aggie Harker has half the village convinced that the area is haunted by Adderson’s ghost, in the form of a snake; while the other half is suffering from – “guilty conscience”.

Which, remarkably enough, is the only time in the film that anyone suggests that the villagers ought to feel bad about what they did! Frankly, I was kidding when I suggested that the villagers’ avoidance of the subject of the local “curse” was the circumstances of its origin: on the contrary, no-one seems to feel that arson-homicide is anything to get worked up about. Oh, one or two people do shake their heads over it, but that’s about it.

The really incredible thing, however, is that once Atheris starts her campaign of vengeance, the film actually seems to think we ought to feel sorry for the villagers! – including those involved in the mob violence! Evidently, Adderson’s transgressions are supposed to excuse theirs. This is the usual twisted logic, often seen in badly written movies, that sees characters punished for acts that no-one else knows about.

(In fact, what The Snake Woman needed was a sort of Nightmare On Elm Street scenario, with the next generation being punished for their elders’ sins. However, that kind of dramatic complexity seems to have been beyond Orville Hampton’s abilities.)

“I intend to get to the bottom of these nefarious goings-on, even if I have to leave the pub to do it!”

Murton goes to look around what remains of Adderson’s house. (I wonder if anyone removed the bodies?) He is shocked to find a snake sliding through the wreckage, and hurries away again. The camera then pans back to the house, and we are given our first glimpse of the adult Atheris, standing still and staring. She will do this a lot. Well – “a lot”; for all that she received billing, and dominates the poster art, Susan Travers hasn’t much more than five minutes’ screen-time here, and only about half-a-dozen lines of dialogue.

We then cut straight to the pub, where what one imagines to be the usual order of things is reversed: someone comes staggering in and collapses. (As the people gather around, we notice that no-one looks so much as a day older.) One witness to this event is Colonel Clyde Wynborn, late of His Majesty’s armed forces, who has also chosen Bellingham as the locale for his retirement. (Honestly, what is it with this place!? Has it got tax shelter status, or what!?) The Colonel was an army surgeon, and served in India; and no-one is more surprised than he when, upon examination of the victim, he finds what is, unmistakably, the bite of a king cobra.

Geoffrey Denton’s performance as Colonel Wynborn is the one really enjoyable thing about The Snake Woman (speaking in the serious sense): a professional man hardened by experience, yet open-minded enough to contemplate there being more things in heaven and earth… Wynborn wonders out loud how a man in the north of England could possibly be bitten by a king cobra? – and Barkis puts it all down to, “That black thing, that was born out on the moors, near a score o’ years back!”

As a shrewd judge once said: “People aren’t chocolates. They’re bastard-coated bastards with bastard filling.”

Wynborn gives him a “It’s the twentieth century!” speech, but Barkis tells him this isn’t the first time that such a thing has happened in Bellingham; with Polly the barmaid (too young to have been a party to the mob violence) reflecting bleakly upon Aggie Harker’s insistence that the villagers will be cursed until the serpent-child is destroyed.

Although Wynborn publically scoffs at these stories – “Ridiculous!” – he is sufficiently concerned to write a letter to an old friend and colleague. The action now moves to Scotland Yard, where “the Inspector” (never named) calls to his office Charles Prentice, a young detective interested in the new field of scientific investigation. The Inspector hands Prentice a letter. Upon glancing through it, Prentice dismisses it as the work of a crackpot, only for the Inspector to reprove him, insisting that Colonel Wynborn is a man who deserves to be listened to seriously, however outlandish the story seems. Prentice is dispatched to Bellingham, to see what his new policing methods can make of “The Curse Of The Serpent-Child”.

Charles Prentice, alas, is not one of the bright spots of The Snake Woman. He’s the standard issue cardboard hero, all square shoulders and square head, who combines a smarmy manner and an irritatingly smug, know-it-all attitude with some wonderfully idiotic behaviour. He is, however, quite in spite of himself, impressed with Colonel Wynborn, who starts by making a good-natured reference to Scotland Yard, “Humouring an old man.” Wynborn explains that following the death he witnessed, he checked the local registry, and found that Bellingham and its environs had suffered better – worse? – than one snakebite-related death a year for almost the last twenty years.

However, Wynborn also supplies a logical explanation, of sorts, for these events, telling Prentice about Horace Adderson and suggesting that his snakes, and their descendants, are responsible for these deaths.

“Well, goodbye, doctor! So sorry you couldn’t join us for the arson-homicide!”

(By the way, king cobras, as their scientific name, Ophiophagus hannah, indicates, are snake-eaters. If Adderson’s snakes did get out and breed, the locals might have cause to be grateful to Atheris, for keeping the local population under control.)

Wynborn goes on to speak of Adderson’s work – and interestingly, praises Adderson, speaking quite casually of his treatment of Martha’s mental illness (but how did he know?) – and about Aggie, and her attempts to get the baby killed. Wynborn adds that some of the snakebite victims did not die right away, but lived long enough to insist they had not been attacked by a snake at all, but by a beautiful girl…

“Maybe science can explain everything on this earth; I can’t,” he concludes.

(Wynborn’s unconcerned reaction to Adderson’s research is troubling not just because of the Colonel’s role as the film’s voice of reason, but because if Adderson’s conduct really wasn’t that reprehensible – at least within the world of the film – then what does that say about the behaviour of the villagers?)

Prentice announces his intention of calling on Aggie right away. Wynborn questions his not waiting until daylight, but does not try to stop him. Prentice sets out, carrying with him an Indian snake-charmer’s flute borrowed from the Colonel, semi-jokingly, as “protection”. As he crosses the moor, Prentice tries playing it – his choice of tune is recognisable, just, as “Toreador” – and the camera shows us a cobra perched upon a rock – “listening”.

Of course, Atheris herself does have ears, but you just know this a play on the old fallacy of it being the music and not the movement that “charms” the snake. Anyway, the next moment, Prentice hears a noise himself—and Atheris suddenly appears out of the darkness.

Charles Prentice: setting back the cause of heroism since 1910.

Don’t imagine for a moment, though, that The Snake Woman is going to indulge us with any transformation scenes; not even the oblique kind found in Cult Of The Cobra. Instead, we just cut between Atheris as a girl and Atheris in her snaky form (which is realised by footage of at least two different species). So – snake – cut – girl – cut – snake. No transition shot; no nothing. It’s all rather pathetic.

(Oh—and we repeatedly cut between different species of snake, without being given any indication whether they are meant to be the same; whether they’re both meant to be Atheris; or whether one of them is Atheris, and the other the – heh! – “fer-de-lance”.)

So, having been warned that there is possibly a deadly venomous snake-girl lurking on the moors, who is responsible for nearly two dozen deaths, what does Prentice do upon first seeing Atheris? That’s right: he gets amorous. Fortunately for him – unfortunately for us – Atheris is so strangely affected by Prentice’s complete mangling of Bizet that she allows him to put his arms around her. He thus notices how cold she is, although at the same time he somehow fails to notice – or react to – her hilariously un-1910 outfit.

Atheris breaks away and insists on leaving. Prentice asks if he can see her again. Atheris agrees, provided that he will play the flute for her again. “You must go. Aggie Harker is expecting you,” she says. Turning to put his jacket back on, Prentice comments that he never said anything about Aggie—and turns back to find Atheris gone. Puzzled, he walks off, while we – cut – again see that cobra sitting on a rock.

At Aggie’s, Prentice not only finds Aggie waiting for him, but freshly-poured tea on the table. Prentice describes his encounter on the moors; and when Aggie mentions “the serpent-child”, exclaims, “That’s ridiculous!”

Colonel Clyde Wynborn: an oasis of sanity in a desert of lunacy (and bad acting).

“Have you not been told how it is here?” demands Aggie impatiently—and for once, I’m in sympathy with her. Prentice tries to flatter Aggie, suggesting that the two of them can work together to solve the problem, scientifically. He is no match for Aggie, however, who responds that they will do it, “Not with your science, but with mine.”

At that, she begins to claw through a chest containing a jaw-dropping collection of bones, body parts, preserved animals and other, ahem, “ingredients”, until she pulls out a doll, in a dress, with a tail.

“A voodoo doll!” says Prentice, using what I’m sure was a very common expression in England circa 1910. Aggie then ret-cons her failure to murder the child at birth by explaining that since she helped to give it life, she now lacks the power to kill it. “Not that I haven’t tried!” she insists; and, oh, hey, Aggie, don’t worry: we believe you!

Aggie takes the doll back from the bewildered Prentice and props it up against the far wall, then taunts him into drawing his gun and firing at it, three times. “There! It is done! The curse is broken—by science,” Aggie comments, in a masterful piece of stroking. She adds that Prentice will kill – “Her!” – also with three shots.

The next morning, talking things over with Colonel Wynborn, Prentice is horribly embarrassed by the entire experience. Wynborn refuses to dismiss it, however, and reacts to Prentice’s description of the girl as being cold to touch. Here he produces Murton’s notes (where did he get those?), reading out the description of Atheris’ birth. Prentice scoffs rather rudely, and tells him he sounds like Aggie.

Smug jackasses. What have we done, that they always have to inflict upon us smug jackasses?

She sure does wear a lot of eye-liner and mascara for someone with no eyelids.

The next snakebite victim is an adolescent boy; and instead of taking him to a doctor, the locals who find him carry him into the pub. (Maybe Bellingham never bothered to hire a replacement after Murton left; or maybe life in Bellingham is such that, whoever you’re looking for, he’s likely to be at the pub.) “Something’s got to be done!” exclaims Polly. “Killing young boys in broad daylight, now!” Yes, outrageous behaviour for a demon serpent-child!

As it turns out, Murton is, in fact, at the pub. He mutters about how it must just be snakebite; that it can’t be— And then he scuttles off.

“Poor man,” comments Barkis. “It’s affecting his mind.” Not believing in demon serpent-children, that is.

Wynborn and Prentice also just happen to be at the pub. “Something’s bothering you, Colonel,” comments the scientific mastermind. Wynborn points out not only the time of the attack, but that this one was not by a king cobra at all, but by a fer-de-lance…which he manages to determine at a glance. Oddly, Wynborn decides that this event dispenses with the snake-girl theory, even though he was the one who raised the possibility of some of Adderson’s snakes surviving and breeding in the first place.

Having spent the day swilling down Barkis’s best, Darrow, the father of the boy killed, now decides he’s going to have his revenge, and staggers out of the pub and up onto the moors. Barkis, obviously a good friend and a responsible publican, lets him go with no more than a token protest. We next see Darrow beating the bushes with a pitchfork, while human-Atheris watches from nearby. He finds, in any case, a snake, and sets about killing it, until human-Atheris abruptly becomes snake-Atheris, and intervenes…

Cut………………………………………………..cut………………………………………………..cut.

When the body is found, a dead snake – a fer-de-lance – is lying next to it (and that one really is a fake). As the king cobra watches from its favourite perch, Prentice declares the case closed. Fortunately, others are more open-minded, and more observant. Wynborn for one, who has seen that Darrow died of cobra bite; and Murton, for another, who now heads once more for the Adderson ruins armed with a shotgun. He shouts for Atheris, telling her he’s sorry, but— She appears – cut – and disappears – cut – and Murton gets bitten on the ankle. So much for retirement in Bellingham.

The next morning, Wynborn again speaks about Adderson’s venom-treatments of Martha, showing a mysteriously comprehensive knowledge of the scientist’s work, and suggests – *shudder* – that Aggie was right all along; that Adderson’s child was born with snake-like characteristics. Prentice reacts with scorn and outrage, not for the theory per se, but for the suggestion that, “That beautiful girl I met could be a—!”

You know, this film’s attempt to posit its inevitable conclusion as The Great Romantic Tragedy might have been just a tad more effective if Prentice had known Atheris for longer than three minutes.

Anyway, Wynborn wearily gives it up, and tells Prentice to go back to London, “Where things are exactly as they seem. You’re out of your element here.” That jab sends Prentice into a complete snit, and he storms off to pack his bags.

Jackass.

But, sadly, we’re not rid of him just yet. Leaving Wynborn’s house, Prentice waits for his train at – oh, you’ll never guess! – the pub. No, really! As he writes up his case notes – in which, we apprehend, the term “old crackpot” figures extensively – Polly tells him how sorry everyone is that he’s leaving (speak for yourself, girl!); that they really thought he would have taken care of the serpent-girl.

“Oh, Charles! No-one can mangle great music quite like you!”

Prentice keeps insisting on a logical explanation, whereupon Polly makes wry remarks about “looking where you want to look” and “seeing what you want to see”. This has the effect of making Prentice remember his Inspector’s instructions about, “Making the theory fit the facts, and not vice versa.” Then he has a brainwave [sic.], and pulls from his pocket the snake-charmer’s flute.

Uh, wasn’t that Wynborn’s?

Prentice plays for Polly, who reacts exactly as anyone other than a serpent-child cursed from birth would react; and that, believe it or not, is the great breakthrough that allows Prentice to get over his logical hang-ups and admit that there are more things in heaven and earth. He dashes off, leaving for the Colonel – who he assumes, and rightly, will eventually show up at the pub – a message about looking for a girl who appreciates his music.

Prentice wanders over the moors, calling for Atheris and playing the flute. We see the cobra sitting on its rock. Prentice then sees what he thinks is Atheris…only to realise that instead, it’s some kind of skin…

(Two wonderful touches here: firstly, the skin appears to include the outline of a dress; and secondly, it’s so intact, it resembles nothing so much as an inflatable doll!)

You know, I never thought I’d be glad to see Aggie Harker, but such is the cumulative effect of Charles Prentice. Aggie looms up and points this moron in the right direction, spelling out the significance of the skin for him; because a shed skin that looks just like Atheris turns out to a bit beyond his analytical capabilities. “Then it’s really true?” he says, stunned but accepting.

“You don’t understand! A man gets lonely on the moors at night…”

Or is he? When Aggie tells him that she knew she would find him on the moors, that he has “a destiny”, he can still exclaim, “Ridiculous!”

Aggie brushes this aside and tells him that Atheris isn’t on the moors, she’s at the ruins of her father’s house. Prentice agrees to go there, but insists he’s only doing it to humour Aggie, and has no intention of killing anyone or anything.

Yeah, well. People say that a lot in Bellingham. It doesn’t mean anything.

We are then given another shot of the cobra, still sitting on its rock. So—is that supposed to be Atheris, then, or not?

At his house, Wynborn gets a message from the Inspector, asking him to keep Prentice in town. Naturally, this sends the Colonel to the pub, where in turn he gets the message left by Prentice. “He doesn’t realise the danger!” he exclaims, obviously having formed the same opinion of Prentice’s mental capacity as the rest of us. Thinking that help might be needed, Wynborn asks Polly to “gather the men”, and—

It’s an old-fashioned torch-bearing mob! It’s been a while, by gar!

(And it’s led by Barkis and the constable!!! The village of Bellingham: giving a whole new depth and breadth to the word “shameless”.)

The Mob meets up with Aggie, who tells them that Prentice has gone to, “The home of the EEE-VIL one!” The Mob moves off in that direction, and Aggie smiles delightedly. Nothing like the prospect of a little vigilante justice to get the old heart pumping, hey, Aggie?

Progress in Bellingham:

1890…………………………………………………………………1910

They’ve gone from using one torch to using three.

Meanwhile, The Pride Of Scotland Yard is wandering around in the dark, playing and calling by turns. A snake moves through the undergrowth. Wandering. Playing. Calling. Wandering. Playing. Calling. Then we see the cobra sitting on that same damn rock. The hell—!?

And then we see that same snake – meaning the other snake – which may or may not be supposed to be the same snake – gliding along the ground. Finally (and I do mean finally: you wouldn’t think a sixty-seven minute film could contain this much padding), Prentice makes it to the ruins, where he finds Murton’s body. But a single relevant moment is apparently all they budgeted for, as we then return immediately to wandering, playing and calling.

And at long, long last, human-Atheris appears. In front of that rock, which seems to have teleported from one side of the moor to the other. Prentice makes the following speech:

“Whatever you are, whatever you’ve done, we understand. It wasn’t your fault; it was your father’s. You can’t help being what you are, what he made you, any more than any of us can. If you’ll trust me, I’ll see that no-one harms you. You’ll be safe from others, and safe from yourself. No more killings. Well…will you trust me, Atheris?”

A glance at the clock shows that there are sixty-three minutes and thirty seconds gone in this film.

Wynborn calls, and Prentice answers, turning his head. When he looks back, human-Atheris is gone—but that cobra’s sitting on its rock again! Prentice draws his gun and shoots it—three times.

Sixty-four minutes, five seconds. A new record in the history of male-female betrayal! Congratulations, Charles Prentice!

Oscar Wilde was right: each man kills the thing he’s loved for three-and-a-half minutes.

Aggie smirks in a satisfied way. “Good lord!” exclaims the Colonel, pointing. And there on the ground lies human-Atheris. Even though snake-Atheris was draped over that rock in the preceding shot. A transformation that none of the people standing within three yards of it managed to witness.

“She’s dead, orright,” comments Barkis. And he ought to know.

Back in London, the Inspector finishes reading Prentice’s report. (The voodoo doll lies on his desk.) Then he gets up, crumples the papers, and tosses them on the fire. “Then you’re afraid they won’t believe it, upstairs?” says Prentice. “No, my boy. I’m just afraid they might,” replies the Inspector.

Ah, Scotland Yard! Suppressing the truth since 1910! And of course, the fact that there were at least a dozen witnesses to these events doesn’t hamper the Inspector’s repression of the real story one little bit; because let’s face it, if there’s one thing the people of Bellingham understand, it’s keeping their mouths shut…

Want a second opinion of The Snake Woman? Visit 1000 Misspent Hours – And Counting.

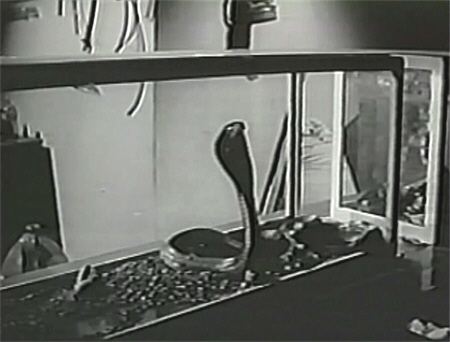

Since we’ve spent so much time lately looking at silly rubber cobras, I thought you might enjoy this real (and righteously pissed off) one.

I’m wondering if the writer had Atheris slay the boy in the vague hope that it would prevent the other killings from feeling like self defense? I mean given how the town acts, it’s not hard to believe she could feel threatened.

LikeLike

I think you – and most of the respondents here – are putting WAY more thought into it than ol’ Orville did.

It’s possible, but the film is so sure that the villagers are the victims that I doubt it would have deemed necessary to push the point.

LikeLike

Murton thinks: “hmm, this lady is suffering from neurotoxic poisoning, and her husband is a herpetologist and the house is full of snakes. Maybe there might be a connection? …nah.”

Let’s see, in 1901-1911 (which is a bit later than we want, but the first UK census was in 1901) you had about 28 births per thousand population per year. So assuming a representative population that’s about six births in a village of 200. That doesn’t seem as though it should be an overwhelming task for a single midwife.

Though perhaps they have Aggie for complicated births and someone a bit less stabby for the simpler ones?

I’m now picturing a set of scenes set during that time lapse, when Aggie repeatedly tries and fails to kill Atheris.

He’s homoeothermic and she’s poikilothermic; it could never have worked. But let’s face it, they still have more in common than many protagonist couples.

LikeLike

Plus there seems to be a distinct lack of a breeding-age population in the town: the dead kid is only young person we see, other than Atheris herself. Hmm…maybe he was killed for putting the moves on her?

The REAL question is, why didn’t Atheris just kill her?

LikeLike

I’m guessing she never went near Atheris’ stamping (slithering?) grounds, and possibly had some protection from her charms and such (since there is an implication of her magic working with the whole “shot three times” thing)?

“Arson-herpicide, too, but I’m probably the only one who cares about that.”

You must know that is simply not true, my dear! 🙂

LikeLike

“He’s homoeothermic and she’s poikilothermic…”

two mismatched cops on the edge, taking it all the way.

but they just might make a love connection.

and Christ said, “You must be either hot or cold.” They rejoiced.

LikeLike

Maybe there are a lot of identical rocks strewn throughout the land (with identical bushes and stuff just happening to be close by).

Every time I see the name Adderson, I think it’s really Anderson spoken by someone with a cold.

I don’t understand. Was Mrs. Adderson mentally ill before (and how much?), and then cured with the snake venom? But now that she’s pregnant, Dr. Adderson is afraid of a relapse? If it really was cured by snake venom, that would be a really big thing, and useful to humanity. Does it also cure Haemophilia, epilepsy, rheumatism, hypertension, and cancer? Except for that side effect of having a snake for a child.

LikeLike

Not really ssseeing the downssside. 🙂

I think the only vaguely ethical sequence of events is that she is mentally ill, she is cured, and then he marries her. Even that isn’t great.

LikeLike

Thinking it over, perhaps her mental illness consisted of having opinions different from her husband? You know, like not wanting to be injected with snake venom when she’s pregnant.

Those uppity women.

I just read a novel set in 1911, and a comment used as an insult (several times) was, “She probably wanted to vote!” We have made some small progress in some ways.

LikeLike

I can only say again what I said to Craig—WAY too much thought! 😀

Given contemporary attitudes to female mental health, I wonder if we might read this as pregnancy, like post-natal depression, being treated as “automatic insanity”?

LikeLike

…mind you, in fairness I should mention that a lot of work has recently gone into snake venom based cancer treatments. Possibly (as with Captive Wild Woman and The Creeper), this came about simply because someone read an interesting article…

LikeLike

Possibly the real objection was that snakes inject people with snake venom without spending hardly any time at university, and don’t have to worry about any pesky oaths about “first do no harm” or anything like that. Totally irresponsible behaviour! Harrumph!

LikeLike

…because just look how Adderson and Murton have their entire careers dictated by the Hippocratic Oath!

LikeLike

It’s the movie mad doctor version. The Hypocritic Oath.

LikeLike

An entire village going through a midwife cwisis. On the bright side, we were spared Aggie being named something like Anna Condon. (Spared at least until Fred Olen Ray used Anna Conda for a small role of his wife Dawn Wildsmith in The Tomb.). Herpetologist named Adderson is ridiculous. If only enough to have an excuse for another drink.

LikeLike

I’m not sure whether the absence of a boom-tish makes it better or worse.

LikeLike

Nominative determinism is real enough to have had serious research done on it…

LikeLike

That’s curious enough to keep me busy for awhile. First thoughts stray towards wondering if Adderson also could have been an accountant. Second thoughts wander to the missed opportunity of Adderdaughter, which would have been very appropriate for this movie and worth at least two drinks.

LikeLike

No steps between “get venom from cobra” and “inject venom in wife?” Isn’t that basically the same as having the cobra inject her directly? Wouldn’t that not make her sane on account of making her dead?

LikeLike

You see, it’s always people like you who stand in the path of progress! In other news, my wife’s funeral is on Tuesday, and I’m interviewing new candidates…

LikeLike

So if you’re exposed to snake venom in the womb, you turn into a snake? A snake that can take human form and spontaneously generate non-period clothes? How could anyone pretend that makes sense? I can see having a toxic touch because the fetus incorporated the venom into its physiology (it’s still impossible, but there’s at least a sliver of logic to it), but “get hit with what snakes use to kill their prey” = “turn into snake” is light-years beyond absurd.

And yet they did it in the 1999 “Lost in Space.” Just to illustrate that godawful screenwriters all drink from the same well, no matter how much time or distance separate them.

LikeLike

Producers are always willing to give the writers a lot of wiggle room. Or I suppose in this case a lot of wriggle womb.

LikeLike

Director Sidney Furie had what I can only describe as an up and down career. His most critically acclaimed movie probably being The Ipcress File. According to his imdb trivia page, he was once in the running to direct The Godfather.

LikeLike